Abstract

This study analysed the leadership approaches that determine one of the components of organisational resilience: situational awareness in business organisations. A lack of situational awareness in leadership results in poor decision making and low organisational resilience, which undermines the continuity and sustainability of the organisation’s activities. This observation prompts the following research question: which leadership methods enhance situational awareness and how are these methods effectively applied in business organisations? This study analysed the situational awareness requirements for leadership through leadership methods. With the help of mixed methods that integrate qualitative and quantitative approaches, an empirical study was conducted in eight European countries; in total, 30 leaders of business organisations were interviewed and 3370 employee questionnaires were analysed. The analysis identified the leadership methods that enhance situational awareness; it also presented the assumptions that determine the effectiveness of these methods. The relationship between leadership methods and situational awareness was found to be mediated by the interaction of the two elements of situational awareness with twelve leadership methods. These findings provide a structured approach to explaining how leadership methods affect situational awareness, thus complementing existing theoretical frameworks and encouraging the development of new theoretical models.

1. Introduction

Leadership awareness is critically important for the sustainability and continuity of organisations. Currently, organisational resilience is becoming an essential factor for operational sustainability in highly uncertain business environments. One of the key components of organisational resilience is situational awareness (SA), which enables management to perceive, interpret, and respond effectively to changing situations. A lack of attention by business leaders to situational awareness results in lower organisational resilience, usually due to a biassed assessment of complex situations and delayed or incorrect decisions.

The scientific literature defines situational awareness as the capacity to make the right decisions. This depends on the perception of the internal environment as well as an understanding of the influences of threats and risks from the external environment. A clear grasp of the current context enables one to foresee future trends in order to adapt and take advantage of them.

The elements of situational awareness (SA) reveal the demands on leadership which are particularly relevant in every condition of uncertainty. Perception is defined as a state of knowledge reflecting a concept of the environment. However, perception requires gathering information: sensing the surroundings, receiving messages from the environment, and interacting directly with the environment. In the context of an organisation, the immediate surroundings are the employees, whose needs and expectations unlock their potential for achieving organisational goals. Comprehension is the environmental assessment, which is not limited to information about the internal environment; it also includes all relevant external environmental factors of an organisation. Not all aspects may be clear and understandable to employees; therefore, it is essential that these aspects are uncovered and explained to them in order to be fully engaged in the achievement of organisational objectives. Projection is the anticipation of future trends, forecasting and spotting opportunities based on previously perceived and assessed information. In this way, projection is considered the result of the first two elements (perception and understanding), which helps achieve organisational goals in times of uncertainty.

Thus, leadership decisions depend on the situational awareness of business leaders that determine the implementation of organisational goals. Scientists define the main requirements of situational awareness in leadership in times of uncertainty as follows: (1) the perception of the internal organisational environment or situation (Ahmad et al., 2021; Kuntz et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2023; Marcazzan et al., 2022; Prayag et al., 2020; Sonnet, 2016; Stanton et al., 2017; Wut et al., 2022) and (2) the comprehension of the relationship between an organisation’s internal and external environments (Kim, 2020; Knipfer & Kump, 2022; Kuntz et al., 2017). In addition to this, scientists highlight the areas that business leaders need to focus on in order to improve situational awareness: (1) the needs and expectations of employees which reveal the internal organisational potential (Kong et al., 2023; Ramachandran et al., 2024; Zhang & Liu, 2022) and (2) maintaining trust in management and the organisation by accepting and solving the organisational issues (Arroyo et al., 2024; Knight & Paroutis, 2017; M. C. Wang et al., 2021).

Enhancing situational awareness (SA) requires continuous training and improvement in leadership skills. In business organisations, this takes place under specific conditions such as a rapid response to environmental changes. This is achieved by integrating theory and practice, known as “learning by doing” (Day et al., 2014; Groves & Feyerherm, 2022; Hezlett, 2016). The quality of managerial abilities, skills, or competences is not determined by their intentions or aspirations but by their real actions (Boyatzis, 1991). These actions are revealed in daily activities through the application of leadership methods, the effectiveness of which is measured by the final results.

Thus, the scientific literature has already revealed the requirements for leadership in times of uncertainty, identified areas for strengthening situational awareness, and explained the specifics of strengthening leadership skills in business organisations. However, there is no research that indicates specific leadership methods that strengthen situational awareness. Considering this, the following research question has emerged: which leadership methods enhance situational awareness and how are these methods effectively applied in business organisations?

This research is based on the approach that there is a relationship between relevant leadership methods and situational awareness. Therefore, it is assumed that the effective application of these methods determines the results of situational awareness.

To address the research question, this paper is structured as follows. Section 1 introduces the study, while Section 2 reveals the meaning of situational awareness and the influence of leadership methods on strengthening it. Section 3 outlines the methodology applied and Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 discusses the results and Section 6 presents the conclusions. Section 7 outlines the limitations and recommendations for future research.

2. Theoretical Framework

The leadership methods that business leaders use in their daily activities reflect the expression of their skills and competencies (Boyatzis, 1991). Although these leadership methods are goal-oriented, a variety of tactics are used for their implementation. As a result, leadership methods can be defined as combinations of managerial actions that encompass the practises and processes supported in an organisation (Gigliotti, 2019; Šilingienė & Stukaitė, 2021; Giles, 2016). The application of practises refers to routines or procedures in daily activities that shape employee behaviour and enhance productivity and teamwork. Practises show how a business leader applies existing knowledge and skills to the organisational activities, including problem solving and interpersonal relationships (Araujo et al., 2022; Cohen & Vainberg, 2023; Gravina et al., 2021). Support processes, on the other hand, refer to the set of actions necessary for continuous and optimal performance, typically involving monitoring, analysis, or continuous improvement. It reveals how business leaders plan, organise, and implement strategies to ensure the effective achievement of organisational goals (Groves & Feyerherm, 2022; Soderstrom & Weber, 2020).

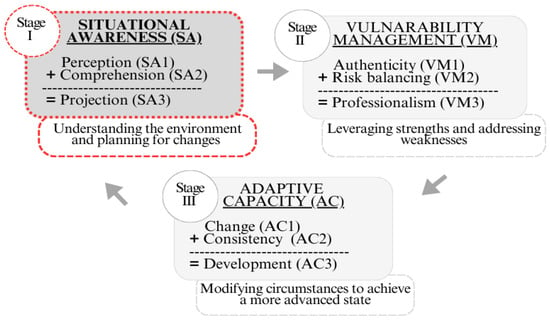

Under conditions of uncertainty, the achievement of organisational goals is largely dependent on organisational resilience—the capability to not only cope successfully with adverse and uncertain situations but also transform into the best version of oneself (Kim, 2020; Lv et al., 2018). As organisational resilience is understood as a latent, hypothetical phenomenon, its homogenous study is challenging. For this reason, the main components of organisational resilience that are commonly analysed are the following: situational awareness, vulnerability management, and adaptive capacity (Hillmann & Guenther, 2021; Kuntz et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2013; Näswall et al., 2015; M. C. Wang et al., 2021). (1) Situational awareness is defined as an organisational capability to identify and assess its current environment, future threats, and opportunities. It is associated with perception, comprehension, and projection (Ahmad et al., 2021; Andersson et al., 2019; Barasa et al., 2018; Duchek, 2020; Hillmann & Guenther, 2021; Ma et al., 2018; Stanton et al., 2017). (2) Vulnerability management is defined as an organisational capability to unlock its potential and manage risks, and it is associated with authenticity, risk balancing, and professionalism (Branzei & Fathallah, 2023; Galaitsi et al., 2023; Sincorá et al., 2023). (3) Adaptive capacity is the capability of an organisation to adapt quickly and effectively to changing conditions; it refers to change, consistency, and development (Beck et al., 2024; Boylan & Turner, 2017; Prayag et al., 2020).

Situational awareness is thus considered the first and most basic component of organisational resilience. It is the basis for modelling the second component, vulnerability management, and the third component, adaptive capacity. The interaction cycle of all three components of organisational resilience is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Interaction cycle of components of organisational resilience.

As can be seen from the above picture, the ultimate goal of organisational resilience is the capability to change circumstances in order to achieve a state of enhanced resilience (Stage III). However, this requires the ability to exploit one’s strengths and weaknesses (Stage II). This is only possible when the environment is understood, and change is planned (Stage I). This means that the immediate internal environment must be perceived first, i.e., the needs and expectations of employees (Perception), followed by the external environment, i.e., the risks and threats it poses to the internal environment (Comprehension). Only after these processes are balanced can solutions be expected in planning and implementing future goals (Projection).

Situational awareness is the result of constant monitoring, data collection, and analysis of the environment to identify potential problems and challenges in time. Situational awareness enables an organisation to respond quickly to the unexpected events and make proactive decisions to mitigate their negative impact. The main elements of situational awareness are as follows: (a) perception involves the ability to notice and identify current and potential factors that may affect the organisation; (b) comprehension is defined not only as the perception of events but also as the assessment of their causes and potential impact on the organisation (Ahmad et al., 2021; Andersson et al., 2019; Barasa et al., 2018; Duchek, 2020; Ma et al., 2018; Stanton et al., 2017).

Thus, the SA ‘perception’ element requires the (1) perception of the internal organisational environment. This is achieved through gathering information from employees, taking into account their feelings, experiences, and needs (Ahmad et al., 2021; Kong et al., 2023; Kuntz et al., 2017; Näswall et al., 2015). Meanwhile, the SA ‘comprehension’ element requires the (2) comprehension of the external environmental threats to the organisation. In this case, threats should first be disclosed and explained to employees in order to engage them in their resolution (Dirani et al., 2020; Knipfer & Kump, 2022; Ozanne et al., 2022; Ruiz-Martin et al., 2018; Stanton et al., 2017).

For this reason, business leaders should focus on the empathy, listening, and recognition of employees’ needs in order to strengthen the first SA element ‘perception’. Empathy refers to the ability to sense other people’s emotions and situations, listening refers to the ability to communicate effectively and to understand other people’s experiences, and recognising employee needs refers to the ability to identify and solve problems by aligning the expectations of employees and the organisation. (1) In order to build empathy, the leader may hold (A) a personal interview with the employee. This creates a private atmosphere for encouraging openness and a personal connection which helps obtain in-depth information and understand the emotional state of the employee (Blevins et al., 2022; Näswall et al., 2015). Alternatively, the leader can organise (B) an informal meeting with the employee. This meeting is based on a relaxed environment in which the employee interacts with the business leader as an equal. This encourages the employee to express their opinions openly and give direct feedback. It also gives the leader an opportunity to get to know their employees better and helps them to understand their experiences and interests (Prayag et al., 2020; Saleem & Perveen, 2017). (2) In order to strengthen listening skills, the leader can organise (C) a group discussion. This form of communication itself encourages the sharing of ideas and helps in hearing different opinions. In this case, there is a risk that some employees may not want to express their opinions publicly, so they may remain unheard. In any case, this method leads to employee engagement and promotes the improvement in communication skills (Ahmad et al., 2021; Strandberg et al., 2019). In addition, (D) gathering employee feedback can be organised. In this case, employees are asked to provide feedback on various occasions: meetings, events, or other initiatives. The business leader is given the opportunity to gain insights and comments directly from employees. This allows for the quick identification of problems and challenges (Church & Waclawski, 2017). (3) For the better comprehension of employee needs, an (E) anonymous survey can be used. This method ensures a greater flow of information and guarantees openness at work and the freedom to express employee thoughts. This helps identify information that was not disclosed during a personal interview, but there is a risk of losing context or not seeing the details. In any case, an anonymous survey can identify areas of organisational improvement (Gravina et al., 2021; M. C. Wang et al., 2021). Another possible method is (F) working environment monitoring. In this case, the business leader consciously observes the environmental behaviour of employees in the specific working environment. This allows for unbiased information about employee communication and cooperation in various everyday situations. The disadvantage of this method is that employees may change their behaviour, knowing that they are being observed. In any case, employees may feel engaged and trust the organisation when seeing the interest of business leaders in their working environment and efforts to enhance their performance (Tomczak et al., 2018; Wut et al., 2022).

Furthermore, business leaders should focus on transparency, perception of reality, and trust in order to strengthen the second SA element ‘comprehension’. In this case, transparency is associated with employee engagement, perception of reality is associated with the acceptance of the situation, and trust is associated with security. (1) In order to achieve transparency (A), business leaders not only build trust with declarations but also practice trust in their behaviour and decisions. Trust requires that the business leader make decisions not for the benefit of themselves or specific employees but based on a commitment to the organisation. Such decisions may not always be understandable to employees, so the business leader should reveal their meaning. In this way, even unfavourable information should be fully disclosed to employees, explaining its reasons, influence, and possible consequences for the organisation and all its members. This is an essential condition for mutual trust (Barton & Kahn, 2019; Kleynhans et al., 2022; Tao et al., 2022). Alternatively, employees can be (B) encouraged to raise questions in order to examine unclear aspects in a joint discussion. This prevents various interpretations, and employees, instead of discussing rumours and negative emotions, participate in beneficial engagement activities (Kim, 2020; Knipfer & Kump, 2022). (2) Perception of reality is associated with the (C) assessment of the impact of the situation. In this case, it is important to jointly determine how the situation affects the overall well-being of employees at the workplace and the strategic goals of the organisation. A common interpretation of the situation helps in understanding possible challenges more easily (Brill et al., 2024; Stanton et al., 2017). The next step is (D) the organisational consequence assessment. In this case, it is useful to apply risk, impact, financial, or other analyses. The results of these analyses help in accepting the situation and openly acknowledging inevitable changes (Einwiller et al., 2021; Sonnet, 2016). (3) Trust is built (E) by planning the resources needed to adapt to the changed environment, namely the reallocation of budget funds, employee training, using technology tools, and the updating of information databases. When employees see that the organisation is actively planning and preparing for various situations, they feel more secure about their working environment and future (Goyal et al., 2023; Ozanne et al., 2022). In changing circumstances, more attention also needs to be paid (F) to coordinating interactions between different departments, teams, and individual employees of the organisation. This is ensured through constant communication between different units and teams, through regular meetings and collaboration platforms. Employees can also be given access to relevant information. This aims to avoid operational disruptions and ensure the transition to a new operational state, while maintaining the smooth functioning of the entire organisation. When employees see that operational stability is ensured despite changes, they trust the decisions of managers and willingly contribute to the implementation of common goals (Giustiniano et al., 2020; M. C. Wang et al., 2021).

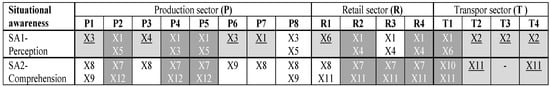

This reveals the dependence of a specific element of situational awareness on the use of specific leadership methods (see Table 1). In Table 1, X1, X2, etc., represent the leadership methods identified in the theory.

Table 1.

Leadership methods that enhance situational awareness.

The effective application of leadership methods is related to the ability of business leaders to assess the weak and strong areas of situational awareness in the organisation in a timely manner. Weak areas indicate which methods need to be adjusted, and strong ones help determine the direction of adjustments. In this way, not only are the professional skills of business leaders developed, but the dynamic development of the entire organisation is also promoted. Importantly, the implementation of the organisational goals usually depends on the management’s ability to apply the right methods in the right situation at the right time.

This literature review formed the basis for this study, the methodology of which is presented in the next section.

3. Materials and Methods

This section reveals the data collection methods, study participants and samples, data analysis methods, study limitations, and ethics.

In order to analyse the management experience in business organisations in applying leadership methods that enhance situational awareness, a qualitative research method was used. Based on previous works (Bodziany et al., 2021; Hillmann & Guenther, 2021; Lee et al., 2013) and other research findings, interviews with leaders of business organisations were chosen to conduct this study. For revealing attitudes of employees towards key aspects of situational awareness, a questionnaire survey method was chosen to conduct the analysis. The research methodology was based on the experiences of previous works (Kuntz et al., 2017; Näswall et al., 2015; Sonnet, 2016; J. Wang et al., 2014) and other authors.

The interviews and questionnaires were both designed based on the theoretical framework of situational awareness, reflecting its individual characteristics. Each characteristic was associated with a separate question. The content was assessed for appropriateness by seven experts in the relevant field, who provided recommendations on the accuracy, clarity, and relevance of the compliance to the research objectives.

The qualitative component—interviews—consisted of two semi-open questions linked to the methods used by business leaders: eliciting employees’ needs and expectations, and disclosing unfavourable information to employees about possible threats to the company. These themes combine two questions from the quantitative survey that indicate the possibilities of employees to share their organisational concerns with management (D1) and learn from their business leaders about rising organisational risks and threats—information availability (D2).

Nine companies from three different industrial sectors took part in the survey, namely manufacturing, food retail, and transportation. These sectors are considered particularly important in times of uncertainty (Boylan & Turner, 2017; Galaitsi et al., 2023; M. C. Wang et al., 2021). The companies were selected to reflect the diverse management challenges they face. Therefore, the companies differ not only in size and geography, but also in their level of autonomy: five companies operate independently as separate economic units, three companies belong to the same trading alliance, and eight business units operate in eight European countries as part of a single multinational company. All these companies share a common commercial status and a profit motive.

The organisations selected for this study were those that had faced uncertainty and agreed to participate in the research. The sample size was calculated using a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. The study population consisted of 14,167 employees, of whom 3370 (23.8%) were surveyed. This sample size allows for reliable data analysis and sector comparisons. In addition, given the different sizes of organisations, the proportion of respondents in smaller companies was higher. This allowed for a more detailed assessment of the managerial characteristics of smaller organisations and, at the same time, ensured the possibility of analysing sector-level trends and comparing their data.

Aspects related to the use of non-random sampling were evaluated. On one hand, the voluntary participation of respondents could have led to greater activity or the inclusion of more motivated employees. On the other hand, it ensured the accessibility of this study, the anonymity of respondents, and the motivation to participate. This allowed the collection of large-scale data in various organisational settings, ensuring sufficient contextual diversity.

Interviews with managers of organisational units were conducted between May 2023 and March 2024. Most interviews were conducted remotely using Zoom and Teams platforms. A quantitative survey was also conducted at the same time. Questionnaires were sent and distributed within organisations using the created questionnaire link.

The interviews were carried out with 30 respondents, and anonymous questionnaires were collected from 3370 employees (see Table 2). Each respondent was coded as follows: production and building material organisations were P1/I, P2/I, and so on; retail sales of food products were R1/I, R2/I, and so on; and transport and logistics services were T1/I, T2/I, and so on.

Table 2.

The number of organisations and their employees participating in the quantitative research survey.

The quantitative data were processed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) software (v.29.0.0) and a survey system. The following calculations were carried out for the analysis of the quantitative data: the estimation of the distribution of the interval variables in accordance with the normal distribution method (the skewness and kurtosis coefficients); the mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD) of the interval variables, and the absolute number (n) and frequencies in percentages (%) of the qualitative variables. Pearson’s Chi-square (X2) test was used to compare qualitative variables between groups, and one-way ANOVA (F) and Kruskal–Wallis (H) methods were used to compare interval variables, considering their distribution and group sizes. In addition, binary regression and linear regression analyses were used to assess the effectiveness of the management methods used. The significance level for a study was set to a p-value less than 0.05, which is statistically significant, and a p-value greater than 0.05, which is statistically not significant.

This study was based on cross-sectional data collected during a single survey, in order to compare different organisational contexts at the same time. This nature of the study allowed us to establish relationships between variables and identify possible trends. In order to reasonably assess causal relationships between variables, a longer-term or ongoing study would be required.

Furthermore, since the data were collected from different employees in the same organisations, there was a possibility of similarity in responses. On one hand, the general organisational environment, culture, and leadership aspects may affect the independence of the data, so a possible internal correlation between respondents should be taken into account. On the other hand, these similarities reveal organisational-level factors and provide information about the leadership methods that are currently being examined.

To conclude the methodological aspects of the study, the research philosophy and ethics were evaluated, as well as the responsibility for the scientific process and the adherence to its values. The voluntary nature of the study participants’ participation was ensured by obtaining their personal consent. They were also fully informed about the study’s objectives, methods, potential risks and benefits, and the possibility of withdrawing from the study at any time without any consequences or obligations.

The next section presents the results obtained from the study.

4. Results

This section explains three types of outcomes. First, it outlines the methods revealed by business leaders that they applied in their daily activities. Next, it analyses the position of employees related to various aspects of resilience. Finally, it examines the effectiveness of the leadership methods applied in terms of organisational resilience outcomes.

4.1. Results of the Qualitative Research Revealing the Leadership Methods Used by Business Leaders

Business leaders seek to perceive the internal organisational environment by understanding the needs and expectations of employees. Therefore, they talk to employees in one-on-one meetings or in personal interview(s) (X1), “hoping for their openness” (P2/I). In this way, they would like to touch on more sensitive topics, to “clarify specific needs” (P4/I) and to understand their problems and challenges (P7/I, R3/I, T1/I). By understanding the individual attitudes of employees, business leaders can react to and assess the personal performance of each employee (P5/II, R2/I, R4/I) (Allen & Lehmann-Willenbrock, 2023; Blevins et al., 2022).

The informal meeting (X2) is used by business leaders because it is a way of socialising with employees outside of work, when employees are rested: “…when they are not pressed by work worries” (T3/I). This could be “during organisational festive events” (T4/I), “during trainings” (T4/II, T4/III), or with a “phone or video call after work hours” (T2/I) (Ramachandran et al., 2024; Zhang & Liu, 2022).

Group discussions (X3) are valued by business leaders because they are “focused on the needs of the whole team or unit” (P4/I) and reveal recurring trends, not just common ones (P6/I, P8/II). Group discussions can involve a large number of employees, and they could engage in regular communication and remotely (P1/I) (Tomczak et al., 2018).

Business leaders use feedback gathering (X4) as valuable employee insight on “any relevant topic” (P3/I, P3/II). Business leaders determine the “impact of specific [company] events or initiatives on [employees]…” (R2/I), and what they benefited from and why (R3/I, R4/III) (Messmann et al., 2022; Susanto et al., 2023).

Anonymous surveys (X5) are used by business leaders to disclose information in specific areas. This is due to the anonymity of the employees encouraging them to express themselves freely and confidently (P8/I, P8/II). If anonymous surveys are used after a personal interview, they reveal information that was withheld during the personal interview (P2/I; P2/II). If anonymous questionnaires are used beforehand, they “reveal areas that need to be addressed during the face-to-face interview” (P5/II) (Church & Waclawski, 2017).

Working environment monitoring (X6) is valued by business leaders for its ability to reveal “employees’ work pace, moods, communication styles…” (R1/I), and to identify “how they [employees] keep to their schedule, where and how much rest they get…” (T1/I). Business leaders might perform physical employee monitoring in their working environment (R1/I) or use some form of remote monitoring (T1/I) (Tomczak et al., 2018).

Business leaders have different perceptions of the need for, and the meaning of, the disclosure of external environmental threats to employees. Some business leaders disclose all adverse information to employees, seeking to build and put emphasis on trust (X7). Trust is seen as the basis for further work and problem solving (P2/II, R2/I) and employee engagement (P4/II, R3/I). Business leaders expect that employees who are focused on common goals will not have time to worry and create negative scenarios and will therefore experience less stress (P5/I; P5/II, R4/II; R4/III) (Aristana et al., 2022; Fatoki, 2024).

Other business leaders, who decide not to disclose all negative information to employees, encourage employees to raise questions (X8). This identifies the areas of greatest concern to employees and focuses on their disclosure (P8/I; P8/II). One of the reasons for restricting information is the confidentiality of certain information (P3/I), but most business leaders believe that employees do not have the capability of the full and correct comprehension of information (P1/I). According to them, a low awareness would hamper both the overall stability of the organisation and the work of individual staff members (P8/II, P7/II). In addition, business leaders believe that information should be limited to specific areas of staff work. Therefore, business leaders encourage staff to ask questions that are limited to their direct job responsibilities “so that there is no unnecessary talk or interpretations…” (R1/I) (Brill et al., 2024; Tao et al., 2022).

Business leaders assess the potential impact of unforeseen events (X9) when deciding to limit the disclosure of adverse information to employees. This impact analysis relates to the primary duties of employees and their mental health in the workplace (P1/I; P1/II, P6/I; P6/II, P8/I, P8/II) (Fatoki, 2024; Goyal et al., 2023).

There are business leaders who would like to limit the disclosure of adverse information; nevertheless, they emphasise the need to disclose certain risks because of the need to prepare for adverse and uncertain situations (T1/I). In this case, business leaders perform with their employees’ consequence assessment (X10) (Ozanne et al., 2022).

Business leaders who restrict the disclosure of adverse information, as well as those who fully disclose it, perform resource planning (X11). This obliges business leaders to disclose at least a limited amount of unfavourable information in the expectation of employee engagement (T2/I, T4/I, T4/III, T4/IV) and assistance in mobilising the means of work in order to retain customers (R1/I, T1/I). By contrast, business leaders who provide full disclosure see resource planning as a joint commitment by business leaders and employees to preserve company activities. In this case, business leaders emphasise the impact of employee advice and skills on the success of the organisation (R2/I, R3/I, R4/III) (Goyal et al., 2023; M. C. Wang et al., 2021).

Business leaders who disclose full adverse information to employees perform coordination of interactions (X12). This leads to the coordination of decisions and actions between groups and departments, eliminating the burden of personal responsibility (P2/I, P2/II, P4/I, P4/II, P5/II) (Marcazzan et al., 2022; Soderstrom & Weber, 2020).

4.2. Results of the Quantitative Research on Weaknesses in Organisational Situational Awareness

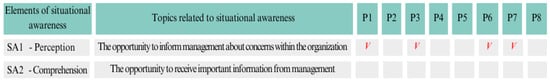

First, the results of the situational awareness domains of manufacturing enterprises are analysed. The gaps in SA “Perception” (SA1) are revealed by the answers to question No. D1, which show the proportion of employees who could share their organisational concerns with the management. Only a small proportion of employees were identified in this way, so this would be a problem in most companies: 29.8% (P1), 26.0% (P3), 24.2% (P6), and 29.0% (P7) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of employee responses in manufacturing sector enterprises.

The situational awareness weaknesses in manufacturing sector enterprises are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Situational awareness weaknesses in manufacturing sector enterprises.

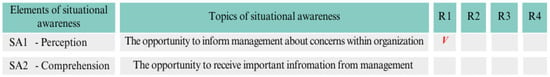

The results in the areas of situational awareness of retail enterprises are analysed below. The gaps in “Perception” (SA1) of situational awareness are revealed by the responses to question No. D1 in enterprise R1, which show that only 25.3% of employees share their organisational concerns with management (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of employee responses to questions in retail sector enterprises.

The weaknesses of the situational awareness of retail sector enterprises are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Situational awareness weaknesses in retail sector enterprises.

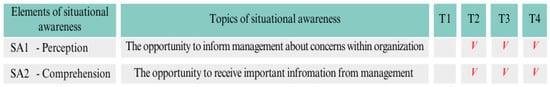

Finally, the results in the areas of situational awareness in the transportation sector are analysed. The gaps in SA “Perception” (SA1) are revealed by the answers to question No. D1. They show that only a small proportion of employees share their organisational concerns with management: 16.1% (T2), 26.4% (T3), and 16.2% (T4). The gaps in SA “Comprehension” (SA2) are identified by the responses to question No. D2, which reveal the extent to which employees have access to information about the company from management. The answers show that only a small number of employees see this possibility: 22.6% (T2), 23.6% (T3), and 18.2% (T4) (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of employee responses in transportation sector enterprises.

The weaknesses of situational awareness in transportation sector enterprises are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Situational awareness weaknesses in transportation sector enterprises.

In light of the identified situational awareness (SA) weaknesses, the impact of the leadership methods in management on situational awareness outcomes is further analysed.

4.3. Effectiveness of the Use of Leadership Methods on Situational Awareness Outcomes

In the analysis of SA “Perception”, the most effective method of leadership was identified as the personal interview (X1). It is this method that increases the likelihood that employees will have the opportunity to talk to their business leaders about their organisational concerns by almost three times (OR = 2.71, p < 0.001). In addition, effective methods could be the anonymous survey (X5) and feedback gathering (X4) (see Table 6).

Table 6.

The effectiveness of SA “Perception” leadership methods.

In the analysis of SA “Comprehension”, the most effective leadership method used was identified as emphasis on trust (X7). It is the use of this method that increases threefold the likelihood that employees learn from business leaders specifically about what is taking place in the organisation (OR = 3.08, p < 0.001). In addition, the use of the methods of coordination of interactions (X12) and resource planning (X11) were found to be effective (see Table 7).

Table 7.

The effectiveness of SA “Comprehension” leadership methods.

A situational awareness map was drawn up, considering the leadership methods used by the companies participating in this study. Methods that were applied effectively are marked in dark grey (method codes are shown in white); those that were ineffective are marked in light grey (method codes are underlined); and those that yielded no results are not marked and not crossed out (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Situational awareness results map.

This map presents the impact of a specific leadership method on the weaknesses and strengths of the analysed companies. Leadership weaknesses indicate the inefficiency of the methods used and the need to adjust them; leadership strengths reveal the effectiveness of the methods and the possibility of using strengths to correct weaknesses. Meanwhile, neutral areas indicate the unsuccessful use of leadership methods, given that certain actions of business managers are not sufficient in ensuring the results of situational awareness.

A detailed analysis of the results allows us to consider the assumptions of the effectiveness of leadership methods, which are explained in the next section.

5. Discussion

This section reveals the influence of leadership methods on SA results, provides the assumptions of effectively applied methods, and explains significant differences between sectors.

The results of SA “Perception” are due to the possibility for employees to express their concerns directly to management. In this area, leadership methods were applied effectively in six companies, neutrally in two companies, and ineffectively in eight. When employees do not have the opportunity to make their organisational views known to management, they do not feel important, and do not see support from business leaders or share their concerns with nonredundant contacts (Knipfer & Kump, 2022). Without knowing the employees, business leaders cannot fully understand the internal organisational environment, which hinders change management. “Perception” requires business leaders to determine employees’ moods, attitudes, behavioural motives, and concerns, as employees represent the main organisational potential for change planning (Zander, 2020).

Business leaders effectively combined a personal interview (X1) with a group discussion (X3), with anonymous surveys (X5), with feedback gathering (X4), or with working environment monitoring (X6). This implies that these methods helped business leaders understand the mindset and concerns of employees, which allowed them to match their needs with organisational ones and to define the necessary changes. Providing the necessary attention and support promotes employee involvement in addressing the organisational challenges (Ahmad et al., 2021; Blevins et al., 2022; Näswall et al., 2015).

In one of the companies (R3), the combination of a personal interview (X1) and feedback gathering (X4) was found to be non-effective, while in other companies in the sector (R2, R4), it proved to be effective. In R3, the business leader of the company was found to be more focused on the needs of the enterprise rather than on the needs of the employees when using this combination rather than the business leaders of other companies. This supports the theoretical notion that employees become engaged in meeting organisational needs when they first receive the necessary support or assistance themselves (Knipfer & Kump, 2022).

The SA results of “Comprehension” are determined by where employees learn about what is taking place in the organisation. In this area, leadership methods have been used effectively in seven companies, neutrally in six, and ineffectively in three. Employees need to understand the organisational issues in order to be able to contribute to their solution. If business leaders do not provide direct information, employees follow rumours and create negative scenarios, wasting time and energy (Kim, 2018; Knipfer & Kump, 2022; Nguyen et al., 2022).

Emphasis on trust by business leaders (X7), combined with the coordination of interactions (X12) or with resource planning (X11), resulted in employee engagement in a variety of adversity and uncertainty management processes. Feeling trusted by management and understanding the complexity of the situation, they were able to objectively assess their capabilities and mobilise their efforts to overcome the difficulties (Barton & Kahn, 2019; Giustiniano et al., 2020). In addition, the combination of consequence assessment (X10) with resource planning (X11) helped staff engage in the necessary activities, taking into account the anticipated changes and possible difficulties (Giustiniano et al., 2020; Kleynhans et al., 2022).

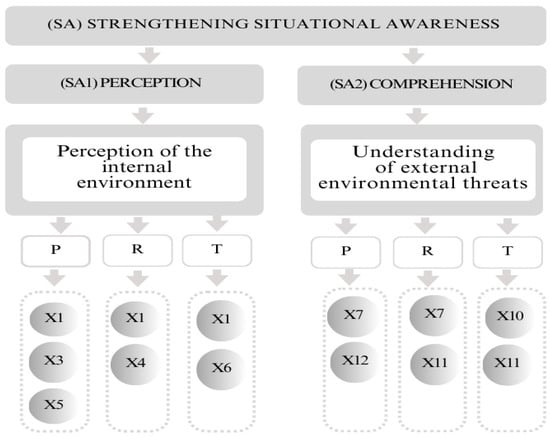

The most effective leadership methods are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Effective application of leadership methods strengthening situational awareness.

As can be seen from the table, companies are effectively using a combination of leadership methods which vary from sector to sector.

When communicating with employees to determine their needs and expectations, leaders in all sectors used personal interviews. However, depending on the sector, it was combined differently; manufacturing companies used it together with group discussions and anonymous surveys, trade companies used it only with feedback gathering, and transport companies used it only with monitoring the working environment. These differences reflect the specifics of the sector’s activities; in the manufacturing sector, the coordination of teamwork is important; in the trade sector, the emotional involvement of employees is important; and in transport sector, the operating conditions are important (Arghode et al., 2022; Blevins et al., 2022; Susanto et al., 2023).

When providing employees with information that was unfavourable to the organisation, leaders usually emphasised the importance of trust. In manufacturing companies, this was combined with the coordination of mutual interactions, and in trade companies, it was combined with resource planning. Meanwhile, in transport companies, resource planning was combined with the assessment of the consequences of an unfavourable situation. This shows that the management decisions in each sector are based on what is most important in it—cooperation, flexibility, or risk management (Fatoki, 2024; Ozanne et al., 2022; M. C. Wang et al., 2021).

Thus, different combinations of leadership methods reflect the nature of each sector’s operations, leadership priorities, and sensitivity to specific challenges. This shows that the effective application of methods requires a contextual approach to maintain stability in adverse and uncertain situations.

6. Conclusions

The relationship between leadership methods and situational awareness has been revealed. It is based on the interaction of two elements of situational awareness with twelve leadership methods. The impact of the application of these methods on the results of situational awareness has been examined in order to identify areas requiring improvement.

In manufacturing and trade sector companies, weak areas are related to the ability to perceive the potential of the internal environment (Perception). In transport sector companies, these are also gaps in the perception of the potential of the internal environment (Perception) and limited employee involvement in solving organisational problems (Comprehension).

The prerequisites for applying effective leadership methods to correct weak areas of situational awareness are defined. Appropriate leadership methods enhance situational awareness, but the effectiveness of applying these methods depends on how these methods are combined with each other, taking into account the different specificities of the sector of activity.

Therefore, in order to improve the understanding of the potential of the internal environment, leaders of manufacturing companies should combine personal interviews with group discussions and anonymous surveys. Meanwhile, in retail companies, leaders are suggested to combine personal interviews with feedback collection, and in transport companies, they are suggested to combine them with the monitoring of the work environment. Furthermore, in order to improve employee involvement in solving organisational problems, leaders of transport companies should assess the consequences of an unfavourable situation together with employees and plan organisational resources accordingly.

The application of leadership methods can be systematically improved in order to specifically correct problem areas. In this way, leadership methods become a practical tool for strengthening situational awareness, which directly contributes to organisational resilience. A resilient organisation not only responds to present challenges, but also evolves, changing its initial state (overcoming crises), adapting to geopolitical changes, recovering from disruptions, and maintaining a strategic direction.

7. Limitations and Future Research

Limitations of research: This study represents data from companies from three sectors of activity, so there may be difficulties in applying the findings to other industries or businesses. It would be interesting to see whether the research methodology developed would be suitable for other sectors, such as healthcare or education.

This representative study was conducted in eight countries, which gives grounds to claim reliable research results. On the other hand, the study was conducted in European countries, which is a unifying geographical location, so we cannot claim that the research results would be the same on another continent, because national cultural differences and different work and organisational cultures are at play.

As the companies participating in the study operate in different EU countries, national cultural and regulatory differences may affect the behaviour of business leaders and employees. Cultural differences may lead to different leadership styles, employee engagement practises, and levels of communication transparency. Meanwhile, regulatory differences may lead to different procedures for obtaining and providing information. The impact of these differences was not analysed in the study, as it aimed to provide more general insights and trends that would be relevant to organisations operating both nationally and internationally.

Perspectives for future research: In order to broaden the scope of research on the effectiveness of leadership methods, it would be useful to (1) include in the analysis businesses from other sectors not involved in the current study, thus providing a broader context of the organisational environment; (2) carry out a longitudinal observational study in order to gain a better comprehension of the long-term trends; (3) analyse in more depth the specific leadership methods that have the most significant impact on situational awareness, and to develop targeted training programmes for business leaders; and (4) carry out additional pilot studies to reveal the results of changes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.R., E.Ž. and L.Š.; methodology, V.R., E.Ž. and L.Š.; software, V.R.; validation, V.R., E.Ž. and L.Š.; formal analysis, V.R., E.Ž. and L.Š.; investigation, V.R.; resources, V.R., E.Ž. and L.Š.; data curation, V.R.; writing—original draft preparation, V.R., E.Ž. and L.Š.; writing—review and editing, V.R., E.Ž. and L.Š.; visualization, V.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The questionnaire, research process and data storage description were discussed and approved by the Klaipeda University Research Ethics Committee (protocol code MTEK-06, 26 March 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad, A., Maynard, S. B., Desouza, K. C., Kotsias, J., Whitty, M. T., & Baskerville, R. L. (2021). How can organizations develop situation awareness for incident response: A case study of management practice. Computers & Security, 101, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J. A., & Lehmann-Willenbrock, N. (2023). The key features of workplace meetings: Conceptualizing the why, how, and what of meetings at work. Organizational Psychology Review, 13(4), 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T., Cäker, M., Tengblad, S., & Wickelgren, M. (2019). Building traits for organizational resilience through balancing organizational structures. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 35(1), 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, T. R. D., Jugend, D., Pimenta, M. L., Jesus, G. M. K., Barriga, G. D. D. C., Toledo, J. C. D., & Mariano, A. M. (2022). Influence of new product development best practices on performance: An analysis in innovative Brazilian companies. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 37(2), 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arghode, V., Lathan, A., Alagaraja, M., Rajaram, K., & McLean, G. N. (2022). Empathic organizational culture and leadership: Conceptualizing the framework. European Journal of Training and Development, 46(1/2), 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristana, I. N., Arsawan, I. W. E., & Rustiarini, N. W. (2022). Employee loyalty during slowdown of COVID-19: Do satisfaction and trust matter? International Journal of Tourism Cities, 8(1), 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, P., Berger, L., & Smaili, N. (2024). Navigating between control and trust: The whistleblowing mindset. Journal of Business Ethics, 199(1), 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barasa, E., Mbau, R., & Gilson, L. (2018). What is resilience and how can it be nurtured? A systematic review of empirical literature on organizational resilience. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 7(6), 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M. A., & Kahn, W. A. (2019). Group resilience: The place and meaning of relational pauses. Organization Studies, 40(9), 1409–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T. E., Solansky, S. T., Davis, D. J., & Ford-Eickhoff, K. (2024). Temporal adaptive capacity: A competency for leading organizations in temporary interorganizational collaborations. Group & Organization Management, 49(1), 114–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, D. P., Stackhouse, M. R. D., & Dionne, S. D. (2022). Righting the balance: Understanding introverts (and extraverts) in the workplace. International Journal of Management Reviews, 24(1), 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodziany, M., Ścibiorek, Z., Zamiar, Z., & Visvizi, A. (2021). Managerial competencies & polish SMEs’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic: An insight. Sustainability, 13(21), 11864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R. (1991). The competent manager: A model for effective performance (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Boylan, S. A., & Turner, K. A. (2017). Developing organizational adaptability for complex environment. Journal of Leadership Education, 16(2), 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzei, O., & Fathallah, R. (2023). The end of resilience? Managing vulnerability through temporal resourcing and resisting. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 47(3), 831–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, D., Schnugg, C., & Stary, C. (2024). Collaborative construction of meaning: Facilitating sensemaking moments through aesthetic knowledge generation. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, A. H., & Waclawski, J. (2017). Designing and using organizational surveys (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A., & Vainberg, A. (2023). What drives creativity in the workplace? Exchange and contextual variables in their relationship to supervisor and self-report creativity. Universal Journal of Management, 11(2), 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D. V., Fleenor, J. W., Atwater, L. E., Sturm, R. E., & McKee, R. A. (2014). Advances in leader and leadership development: A review of 25 years of research and theory. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirani, K. M., Abadi, M., Alizadeh, A., Barhate, B., Garza, R. C., Gunasekara, N., Ibrahim, G., & Majzun, Z. (2020). Leadership competencies and the essential role of human resource development in times of crisis: A response to COVID-19 pandemic. Human Resource Development International, 23(4), 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchek, S. (2020). Organizational resilience: A capability-based conceptualization. Business Research, 13(1), 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einwiller, S., Ruppel, C., & Stranzl, J. (2021). Achieving employee support during the COVID-19 pandemic—The role of relational and informational crisis communication in Austrian organizations. Journal of Communication Management, 25(3), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoki, O. (2024). Inclusive leadership and employee voice behaviour: Serial mediating effects of psychological safety and affective commitment. Administrative Sciences, 14(9), 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaitsi, S. E., Pinigina, E., Keisler, J. M., Pescaroli, G., Keenan, J. M., & Linkov, I. (2023). Business continuity management, operational resilience, and organizational resilience: Commonalities, distinctions, and synthesis. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 14(5), 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigliotti, R. A. (Ed.). (2019). Competencies for effective leadership: A framework for assessment, education, and research (1st ed.). Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, S. (2016). The most important leadership competencies, according to leaders around the world (Vol. 15). Harvard Business Review. [Google Scholar]

- Giustiniano, L., Clegg, S., Cunha, M. P. e., & Rego, A. (2020). Elgar introduction to theories of organizational resilience (Paperback ed.). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, K., Nigam, A., & Goyal, N. (2023). Human resource management practices and employee engagement. International Journal of Human Capital in Urban Management, 8(4), 2318802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravina, N., Nastasi, J., & Austin, J. (2021). Assessment of employee performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 41(2), 124–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, K. S., & Feyerherm, A. E. (2022). Developing a leadership potential model for the new era of work and organizations. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 43(6), 978–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezlett, S. A. (2016). Enhancing experience-driven leadership development. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 18(3), 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, J., & Guenther, E. (2021). Organizational resilience: A valuable construct for management research? International Journal of Management Reviews, 23(1), 7–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. (2018). Enhancing employee communication behaviors for sensemaking and sensegiving in crisis situations: Strategic management approach for effective internal crisis communication. Journal of Communication Management, 22(4), 451–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. (2020). Organizational resilience and employee work-role performance after a crisis situation: Exploring the effects of organizational resilience on internal crisis communication. Journal of Public Relations Research, 32(1–2), 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleynhans, D. J., Heyns, M. M., Stander, M. W., & De Beer, L. T. (2022). Authentic leadership, trust (in the leader), and flourishing: Does precariousness matter? Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 798759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, E., & Paroutis, S. (2017). Becoming salient: The TMT leader’s Role in shaping the interpretive context of paradoxical tensions. Organization Studies, 38(3–4), 403–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipfer, K., & Kump, B. (2022). Collective rumination: When “problem talk” impairs organizational resilience. Applied Psychology, 71(1), 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D. T., Park, S., & Peng, J. (2023). Appraising and reacting to perceived pay for performance: Leader competence and warmth as critical contingencies. Academy of Management Journal, 66(2), 402–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, J. R. C., Malinen, S., & Näswall, K. (2017). Employee resilience: Directions for resilience development. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 69(3), 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. V., Vargo, J., & Seville, E. (2013). Developing a tool to measure and compare organizations’ resilience. Natural Hazards Review, 14(1), 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., Zhang, M. M., Yang, M. M., & Wang, Y. (2023). Sustainable human resource management practices, employee resilience, and employee outcomes: Toward common good values. Human Resource Management, 62(3), 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.-D., Tian, D., Wei, Y., & Xi, R.-X. (2018). Innovation resilience: A new approach for managing uncertainties concerned with sustainable innovation. Sustainability, 10(10), 3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z., Xiao, L., & Yin, J. (2018). Toward a dynamic model of organizational resilience. Nankai Business Review International, 9(3), 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcazzan, E., Campagnolo, D., & Gianecchini, M. (2022). Reaction or anticipation? Resilience in small- and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 29(5), 764–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messmann, G., Evers, A., & Kreijns, K. (2022). The role of basic psychological needs satisfaction in the relationship between transformational leadership and innovative work behavior. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 33(1), 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näswall, K., Kuntz, J., Hodliffe, M., & Malinen, S. (2015). Employee resilience scale (EmpRes): Technical report. Resilient Organisations. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.-M., Malik, A., & Budhwar, P. (2022). Knowledge hiding in organizational crisis: The moderating role of leadership. Journal of Business Research, 139, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozanne, L. K., Chowdhury, M., Prayag, G., & Mollenkopf, D. A. (2022). SMEs navigating COVID-19: The influence of social capital and dynamic capabilities on organizational resilience. Industrial Marketing Management, 104, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G., Spector, S., Orchiston, C., & Chowdhury, M. (2020). Psychological resilience, organizational resilience and life satisfaction in tourism firms: Insights from the Canterbury earthquakes. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(10), 1216–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S., Balasubramanian, S., James, W. F., & Al Masaeid, T. (2024). Whither compassionate leadership? A systematic review. Management Review Quarterly, 74(3), 1473–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Martin, C., Lopez-Paredes, A., & Wainer, G. (2018). What we know and do not know about organizational resilience. International Journal of Production Management and Engineering, 6(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M., & Perveen, N. (2017). The impact of formal and informal communication in organizations a case study of government and private organizations in gilgit-baltistan. Journal of Business and Management Sciences, 5(4), 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Sincorá, L. A., Oliveira, M. P. V. D., Zanquetto-Filho, H., & Alvarenga, M. Z. (2023). Developing organizational resilience from business process management maturity. Innovation & Management Review, 20(2), 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderstrom, S. B., & Weber, K. (2020). Organizational structure from interaction: Evidence from corporate sustainability efforts. Administrative Science Quarterly, 65(1), 226–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnet, M. (2016). Employee behaviors, beliefs, and collective resilience: An exploratory study in organizational resilience capacity. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/16c5a44a3bfdd0b443c19310e1b3e0cc/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Stanton, N. A., Salmon, P. M., Walker, G. H., Salas, E., & Hancock, P. A. (2017). State-of-science: Situation awareness in individuals, teams and systems. Ergonomics, 60(4), 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, K., Himmelroos, S., & Grönlund, K. (2019). Do discussions in like-minded groups necessarily lead to more extreme opinions? Deliberative democracy and group polarization. International Political Science Review, 40(1), 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, P. C., Syailendra, S., & Suryawan, R. F. (2023). Determination of motivation and performance: Analysis of job satisfaction, employee engagement and leadership. International Journal of Business and Applied Economics, 2(2), 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šilingienė, V., & Stukaitė, D. (2021). Lyderystės kompetencijos raiška Lietuvos organizacijose (1st ed.). KTU leidykla “Technologija”. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W., Lee, Y., Sun, R., Li, J.-Y., & He, M. (2022). Enhancing employee engagement via leaders’ motivational language in times of crisis: Perspectives from the COVID-19 outbreak. Public Relations Review, 48(1), 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomczak, D. L., Lanzo, L. A., & Aguinis, H. (2018). Evidence-based recommendations for employee performance monitoring. Business Horizons, 61(2), 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Cooke, F. L., & Huang, W. (2014). How resilient is the (future) workforce in C hina? A study of the banking sector and implications for human resource development. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 52(2), 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. C., Chen, P.-C., & Fang, S. C. (2021). How environmental turbulence influences firms’ entrepreneurial orientation: The moderating role of network relationships and organizational inertia. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 36(1), 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.-M., Lee, S.-W., & Xu, J. (2022). Role of organizational resilience and psychological resilience in the workplace—Internal stakeholder perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zander, L. (2020). Interpersonal leadership across cultures: A historical exposé and a research agenda. International Studies of Management & Organization, 50(4), 357–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Liu, S.-M. (2022). Balancing employees’ extrinsic requirements and intrinsic motivation: A paradoxical leader behaviour perspective. European Management Journal, 40(1), 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).