The Impact of Digital Content Marketing on Brand Defence: The Mediating Role of Behavioural Engagement and Brand Attachment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review for Conceptual Framework

1.2. Digital Content Marketing (DCM)

1.2.1. Behaviour Engagement

1.2.2. Brand Attachment

1.2.3. Brand Defence

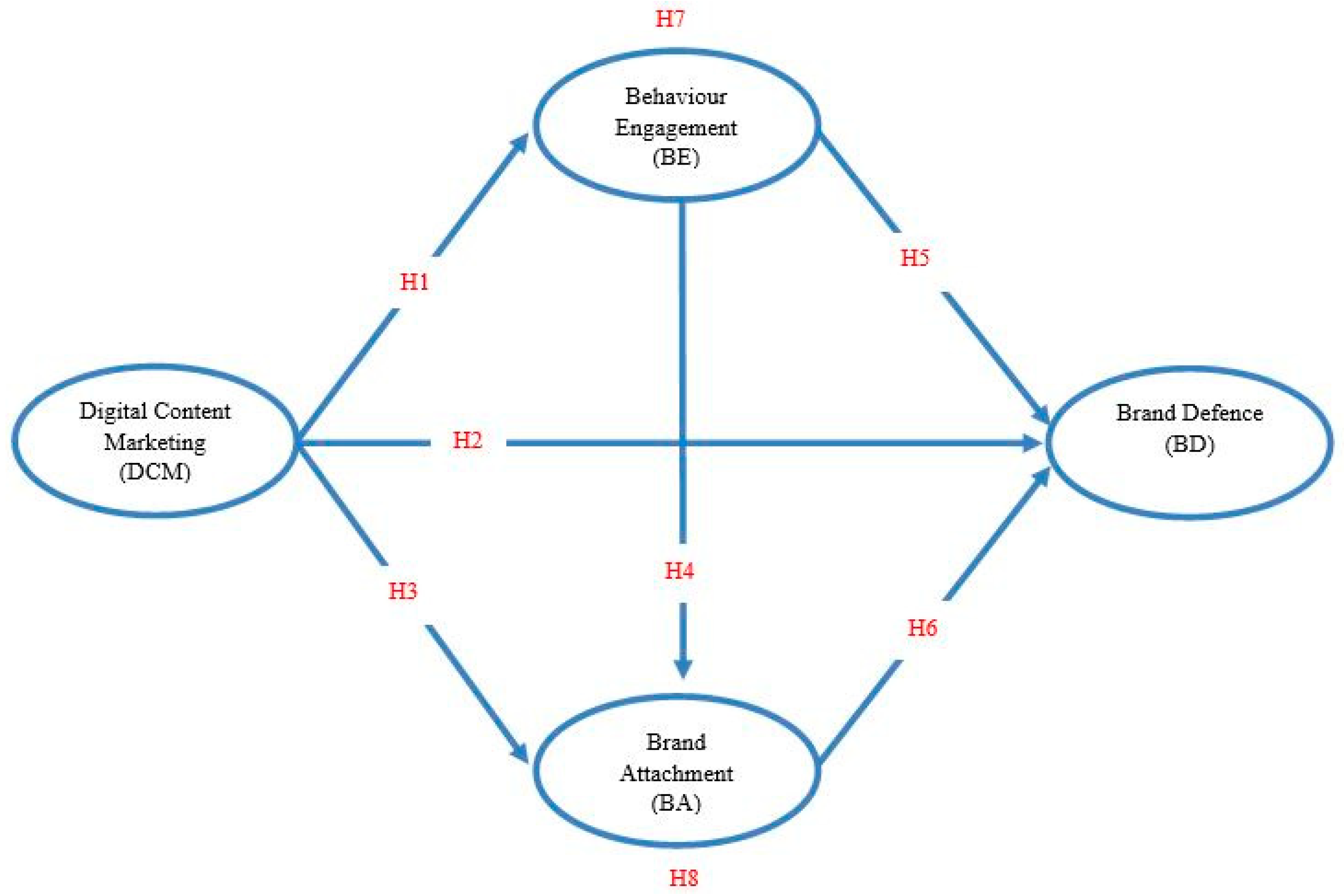

1.3. Hypothesis Development

1.3.1. The Impact of DCM on BE

1.3.2. The Impact of DCM on BD

1.3.3. The Impact of DCM on BA

1.3.4. The Effect of BE on BA

1.3.5. The Impact of BE on BD

1.3.6. The Impact of BA on BD

1.3.7. DCM, BE, and BD

1.3.8. DCM, BA, and BD

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrument Development

- The first section of the surveys collected data on respondents’ age, gender, and monthly income.

- In the second section of the survey questionnaire, the scale items were based on prior research studies.

2.2. Population and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. CFA Findings

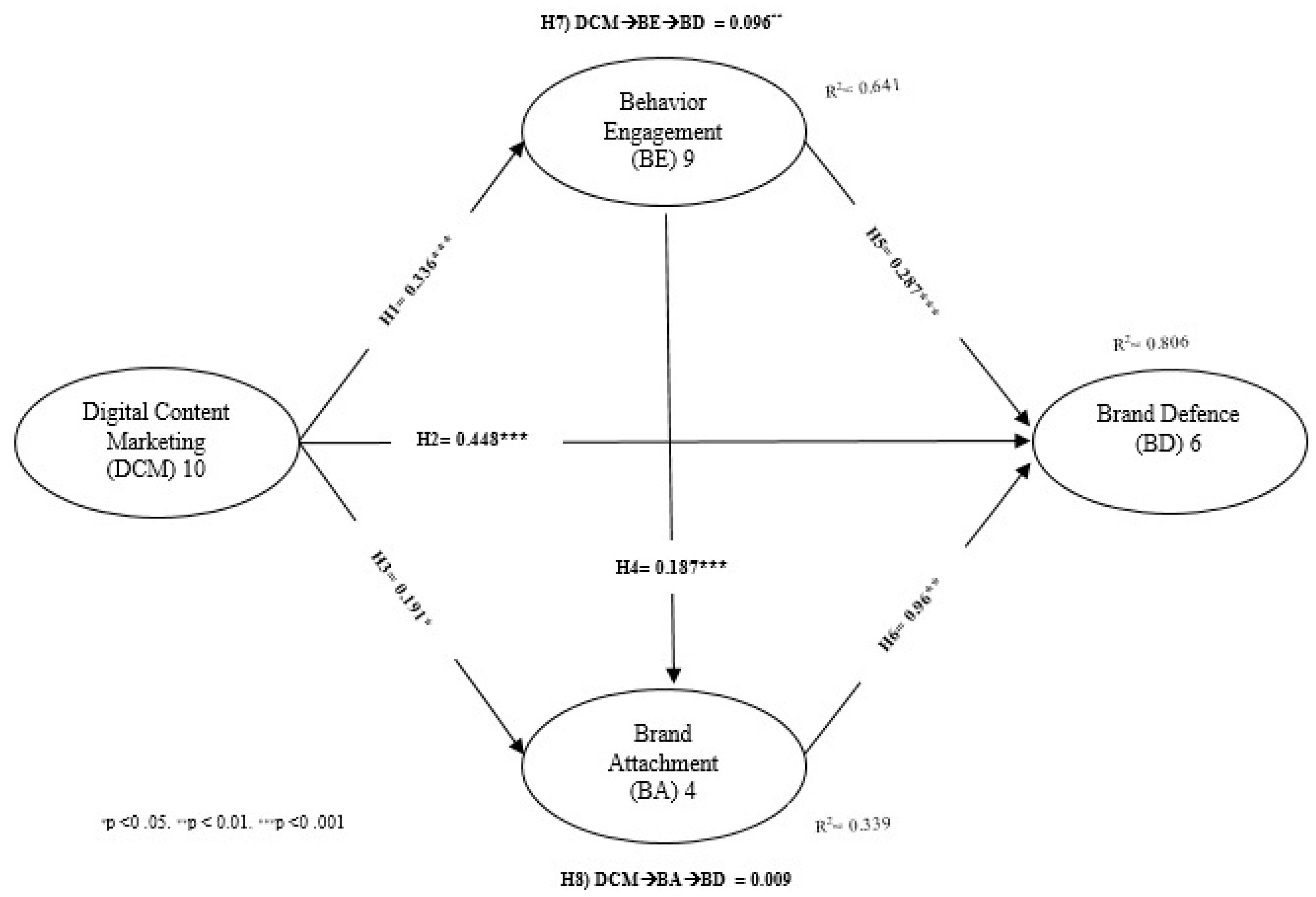

3.2. Hypotheses Finding

3.3. Mediation Effects

4. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Managerial Implications

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Abdallah, G., Barzani, R., Omar Dandis, A., & Eid, M. A. H. (2024). Social media marketing strategy: The impact of firm generated content on customer based brand equity in retail industry. Journal of Marketing Communications, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfraihat, S. F. A., Pechuán, I. G., Salvador, J. L. G., & Tarabieh, S. M. (2024). Content is king: The impact of content marketing on online repurchase intention. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(6), 4017–4030. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F., Dogan, S., Amin, M., Hussain, K., & Ryu, K. (2021). Brand anthropomorphism, love and defense: Does attitude towards social distancing matter? The Service Industries Journal, 41(1–2), 58–83. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nsour, I. A., & Yusak, N. A. B. M. (2023). Impact of social media marketing on the buying intention of fashion products. Res Militaris, 13(3), 617–632. [Google Scholar]

- Alshurideh, M., Anagreh, S., Tariq, E., Hamadneh, S., Alzboun, N., Kurdi, B., & Al-Hawary, S. (2024). Examining the effect of virtual reality technology on marketing performance of fashion industry in Jordan. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 8(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- AlSokkar, A. A., Al-Gasawneh, J. A., Alamro, A., Binkhamis, M., AlGhizzawi, M., & Hmeidan, T. A. (2025). The effectiveness of e-marketing on marketing performance in jordanian telecommunications companies: Exploring the mediating role of the competitive environment. SN Computer Science, 6(1), 58. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, H. M., Sousa, B., Carvalho, A., Santos, V., Lopes Dias, Á., & Valeri, M. (2022). Encouraging brand attachment on consumer behaviour: Pet-friendly tourism segment. Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing (JTHSM), 8(2), 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ardiyansyah, R., & Febrianti, R. A. M. (2022). Understanding the driver of customer purchase decision: The role of customer engagement and brand attachment in batik products. Fair Value: Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi dan Keuangan, 5(4), 1979–1985. [Google Scholar]

- Au, C. H., Ho, K. K., & Law, K. M. (2021). The bright and dark of consumers’ online brand defending behaviors: Exploring their enablers, realization, and impacts. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 31(3), 171–191. [Google Scholar]

- Awang, P. (2015). SEM made simple: A gentle approach to learning structural equation modeling. MPWS Rich Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Bilondatu, R. N. P., & Tjokrosaputro, M. (2023). The role of brand attachment to the antecedents of brand passion. International Journal of Application on Economics and Business, 1(1), 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougie, R., & Sekaran, U. (2019). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, T. T., Tran, Q. T., Alang, T., & Le, T. D. (2023). Examining the relationship between digital content marketing perceived value and brand loyalty: Insights from Vietnam. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 2225835. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, J., Rahman, M. M., Taylor, A., & Voola, R. (2019). Feel the VIBE: Examining value-in-the-brand-page-experience and its impact on satisfaction and customer engagement behaviours in mobile social media. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 46, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X., & Qasim, H. (2021). Does E-Brand experience matter in the consumer market? Explaining the impact of social media marketing activities on consumer-based brand equity and love. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(5), 1065–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, M., Harrigan, P., & Xu, Y. (2022). Customer engagement in online service brand communities. Journal of Services Marketing, 36(2), 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S., & Workman, J. (2011). Gender, fashion innovativeness and opinion leadership, and need for touch. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 15(3), 363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, P. S., Rita, P., & Santos, Z. R. (2018). On the relationship between consumer-brand identification, brand community, and brand loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 43, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Set correlation and contingency tables. Applied Psychological Measurement, 12(4), 425–434. [Google Scholar]

- Dalman, M. D., Buche, M. W., & Min, J. (2019). The differential influence of identification on ethical judgment: The role of brand love. Journal of Business Ethics, 158, 875–891. [Google Scholar]

- Datareportal. (2024). The state of digital in Jordan in 2024. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-jordan (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Davis, S. V., & Dacin, P. A. (2022). This brand is who I am…or is it? Examining changes in motivation to maintain brand attachment. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(7), 1125–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics. (2024). Population of Jordan in 2024. Available online: https://dosweb.dos.gov.jo/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Dewi, I. A. K., Yudhistira, P. G. A., & Agustina, N. K. W. (2022). Impact of digital content marketing on tourist visit interest to melasti beach: The mediating role of social word of mouth. Jurnal Manajemen Teori Dan Terapan, 15(2), 286–299. [Google Scholar]

- Eltokhy, K. E., Gunied, H., & Essam, E. (2024). Role of social media content marketing on brand image: A case study on mobile service providers in Egypt. Insights into Language, Culture and Communication, 4(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezekiel, A. O. (2022). The matic exploratory of content marketing for the fourth industrial revolution. Indonesian Journal of Business Analytics, 2(2), 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadhavi, P., & Sahni, H. (2020). Analyzing the “mindfulness” of young Indian consumers in their fashion consumption. Journal of Global Marketing, 33(5), 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdón-Salvador, J. L., Gil-Pechuán, I., & Tarabieh, S. M. (2024). Effect of social media influencers on consumer brand engagement and its implications on business decision making. Profesional de la Información, 33(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Matthews, L. M., & Ringle, C. M. (2016). Identifying and treating unobserved heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: Part I—Method. European Business Review, 28(1), 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, P., Roy, S. K., & Chen, T. (2021). Do value cocreation and engagement drive brand evangelism? Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 39(3), 345–360. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M., & Casalo Arino, L. V. (2016). Consumer devotion to a different height: How consumers are defending the brand within Facebook brand communities. Internet Research, 26(4), 963–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 98, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L. D., Glynn, M. S., & Brodie, R. J. (2014). Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(2), 149–165. [Google Scholar]

- Hollebeek, L. D., & Macky, K. (2019). Digital content marketing’s role in fostering consumer engagement, trust, and value: Framework, fundamental propositions, and implications. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 45(1), 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ilhan, B. E., Kübler, R. V., & Pauwels, K. H. (2018). Battle of the brand fans: Impact of brand attack and defense on social media. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 43(1), 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, M., Roy, S., & Mansoor, B. (2015). Will you defend your loved brand? In Consumer brand relationships: Meaning, measuring, managing (pp. 31–54). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, S., & Yi, J. (2020). What makes followers loyal? The role of influencer interactivity in building influencer brand equity. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29(6), 803–814. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. K., & Hong, H. (2011). Fashion leadership and hedonic shopping motivations of female consumers. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 29(4), 314–330. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J., & Nayak, J. K. (2019). Consumer psychological motivations to customer brand engagement: A case of brand community. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 36(1), 168–177. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V., & Kaushik, A. K. (2020). Does experience affect engagement? Role of destination brand engagement in developing brand advocacy and revisit intentions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 37(3), 332–346. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M. W., Teng, H. Y., & Chen, C. Y. (2020). Unlocking the customer engagement-brand loyalty relationship in tourism social media: The roles of brand attachment and customer trust. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 44, 184–192. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A. S. (2019). Antecedents of consumers’ engagement with brand-related content on social media. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 37(4), 386–400. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, J., Quoquab, F., & Mohamed Sadom, N. Z. (2021). Mindful consumption of second-hand clothing: The role of eWOM, attitude and consumer engagement. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 25(3), 482–510. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, R. B., & Kasamani, T. (2020). Brand experience and brand loyalty: Is it a matter of emotions? Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 33(4), 1033–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J., & Christandl, F. (2019). Content is king–but who is the king of kings? The effect of content marketing, sponsored content & user-generated content on brand responses. Computers in Human Behavior, 96, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-hill series. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C. W., MacInnis, D. J., Priester, J., Eisingerich, A. B., & Iacobucci, D. (2010). Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pektas, S. Y., & Hassan, A. (2020). The effect of digital content marketing on tourists’ purchase intention. Journal of Tourismology, 6(1), 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, R. A., & Kim, Y. (2013). On the relationship between coefficient alpha and composite reliability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 194. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S. K., Singh, G., Japutra, A., & Javed, M. (2023). Circle the wagons: Measuring the strength of consumers’ brand defense. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 31(4), 817–837. [Google Scholar]

- Ruth, P. A. (2021). Fiscal aspects of the fashion industry: The big four global capitals and the Nigerian equivalent. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 9(9), 232–242. [Google Scholar]

- Sawaftah, D., Aljarah, A., & Lahuerta-Otero, E. (2021). Power brand defense up, my friend! Stimulating brand defense through digital content marketing. Sustainability, 13(18), 10266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, K., & Fitzsimmons, J. R. (2022). The effect of brand personality congruence, brand attachment and brand love on loyalty among HENRY’s in the luxury branding sector. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 26(1), 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Shimul, A. S., Faroque, A. R., & Cheah, I. (2024). Does brand attachment protect consumer–brand relationships after brand misconduct in retail banking? International Journal of Bank Marketing, 42(2), 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. (2023a). Content marketing revenue worldwide from 2018 to 2026. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/527554/content-marketing-revenue/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Statista. (2023b). Fashion eCommerce report 2023. Statista retail & trade reports. Available online: https://www.statista.com/study/38340/ecommerce-report-fashion/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Taiminen, K., & Ranaweera, C. (2019). Fostering brand engagement and value-laden trusted B2B relationships through digital content marketing: The role of brand’s helpfulness. European Journal of Marketing, 53(9), 1759–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabieh, S., Gil, I., Salvador, J. L. G., & AlFraihat, S. F. A. (2024). The new game of online marketing: How social media influencers drive online repurchase intention through brand trust and customer brand engagement. Intangible Capital, 20(1), 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M., MacInnis, D. J., & Whan Park, C. (2005). The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(1), 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdat, A., Hafezniya, H., Jabarzadeh, Y., & Thaichon, P. (2020). Emotional brand attachment and attitude toward brand extension. Services Marketing Quarterly, 41(3), 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Schee, B. A., Peltier, J., & Dahl, A. J. (2020). Antecedent consumer factors, consequential branding outcomes and measures of online consumer engagement: Current research and future directions. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 14(2), 239–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, C. B., & Sousa, B. (2020). The brand attachment and consumer behaviour in sports marketing contexts: The case of football fans in Portugal. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 20(1–2), 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasinghe, K. P. W. D. R. (2019). Impact of content marketing towards the customer online engagement. International Journal of Business, Economics and Management, 2(3), 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe, W. D. S. (2023). Impact of content marketing values on brand value co-creation effect: A study on the lubricant industry in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka Journal of Marketing, 9(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, V., Harrigan, P., & Soutar, G. N. (2018). Navigating online brand advocacy (OBA): An exploratory analysis. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 26(1–2), 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, V., Soutar, G. N., & Harrigan, P. (2020). Online brand advocacy (OBA): The development of a multiple item scale. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29(4), 415–429. [Google Scholar]

| Constructs | Items | References |

|---|---|---|

| DCM | Pektas and Hassan (2020) | |

| DCM1 | DC expresses the facts. | |

| DCM2 | DC is important. | |

| DCM3 | I believe that DC is very informative. | |

| DCM4 | DC is a reliable source of information regarding product quality and performance. | |

| DCM5 | DC provides valuable information about products. | |

| DCM6 | DC provides the true image of the goods provided generally. | |

| DCM7 | I believe DC informs accurately. | |

| DCM8 | DC provides important fundamental information on products. | |

| DCM9 | I rely on the accuracy of DC. | |

| DCM10 | DC is a good approach to acquire information about products. | |

| BE | Chi et al. (2022) | |

| BE1 | Using brand X makes me think about the brand. | |

| BE2 | Purchasing brand X stimulates my interest in learning more about the brand. | |

| BE3 | I feel really positive when I use brand X. | |

| BE4 | Using brand X makes me glad. | |

| BE5 | I feel great when I use brand X. | |

| BE6 | I’m pleased to utilise brand X. | |

| BE7 | Compared to other brands of the same product category, I spend a lot of time using brand X. | |

| BE8 | When I utilise items from this product category, I generally use brand X. | |

| BE9 | Brand X is one of the trademarks I usually use when using this product category. | |

| BA | Li et al. (2020) | |

| BA1 | I am feeling personally linked to Brand X. | |

| BA2 | I feel emotionally linked to Brand X. | |

| BA3 | Brand X can represent me. | |

| BA4 | Brand X communicates to others about who I am. | |

| BD | Sawaftah et al. (2021) | |

| BD1 | When others talk about the brand, I defend it. | |

| BD2 | When others talk about the brand negatively, I defend it | |

| BD3 | When others comment negatively about the brand, I talk about it positively. | |

| BD4 | When I hear others talking negatively about brand, I defend it. | |

| BD5 | I try convincing others to purchase the brand. | |

| BD6 | I share the positive aspects of this brand. | |

| Construct Variable | Item | Factor Loading | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Composite Reliability (CR) | Internal Reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Content Marketing (DCM) | DCM1 | 0.717 | 0.532 | 0.929 | 0.928 |

| DCM2 | 0.760 | ||||

| DCM3 | 0.712 | ||||

| DCM4 | 0.722 | ||||

| DCM5 | 0.732 | ||||

| DCM6 | 0.703 | ||||

| DCM7 | 0.713 | ||||

| DCM8 | 0.715 | ||||

| DCM9 | 0.709 | ||||

| DCM10 | 0.731 | ||||

| Behaviour Engagement (BE) | BE1 | 0.818 | 0.631 | 0.919 | 0.905 |

| BE2 | 0.847 | ||||

| BE3 | 0.819 | ||||

| BE4 | 0.825 | ||||

| BE5 | 0.771 | ||||

| BE6 | 0.758 | ||||

| BE7 | 0.810 | ||||

| BE8 | 0.763 | ||||

| BE9 | 0.761 | ||||

| Brand Attachment (BA) | BA1 | 0.776 | 0.587 | 0.946 | 0.927 |

| BA2 | 0.713 | ||||

| BA3 | 0.776 | ||||

| BB4 | 0.765 | ||||

| Brand Defence (BD) | BD1 | 0.832 | 0.678 | 0.892 | 0.875 |

| BD2 | 0.842 | ||||

| BD3 | 0.791 | ||||

| BD4 | 0.729 | ||||

| BD5 | 0.914 |

| Variable | Mean | Level | CE | BA | BD | DCM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE | 4.16 | High | 0.800 | 0.529 | 0.831 | 0.781 |

| BA | 4.11 | High | 0.568 | 0.770 | 0.558 | 0.476 |

| BD | 4.11 | High | 0.609 | 0.569 | 0.829 | 0.823 |

| DCM | 4.16 | High | 0.705 | 0.538 | 0.633 | 0.731 |

| Path: IV→DV | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (H1) DCM→BE | 0.336 *** | 0.067 | 5.041 | 0.000 |

| (H2) DCM→BD | 0.448 *** | 0.047 | 9.659 | 0.000 |

| (H3) DCM→BA | 0.191 * | 0.080 | 2.345 | 0.010 |

| (H4) BE→BA | 0.187 *** | 0.032 | 5.686 | 0.000 |

| (H5) BE→BD | 0.287 *** | 0.037 | 7.832 | 0.000 |

| (H6) BA→BD | 0.096 ** | 0.029 | 3.251 | 0.001 |

| Path: IV→M→DV | β | SE | t | p | VAF % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (H7) DCM→BE→BD | 0.096 *** | 0.024 | 3.748 | 0.000 | 1.94 |

| (H8) DCM→BA→BD | 0.009 | 0.006 | 1.179 | 0.118 | 1.62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

AlFraihat, S.F.A.; Ali, A.M.; Hodaifa, G.; Alghizzawi, M. The Impact of Digital Content Marketing on Brand Defence: The Mediating Role of Behavioural Engagement and Brand Attachment. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040124

AlFraihat SFA, Ali AM, Hodaifa G, Alghizzawi M. The Impact of Digital Content Marketing on Brand Defence: The Mediating Role of Behavioural Engagement and Brand Attachment. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(4):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040124

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlFraihat, Sakher Faisal Ahmad, Ahmad Mahmoud Ali, Gassan Hodaifa, and Mahmoud Alghizzawi. 2025. "The Impact of Digital Content Marketing on Brand Defence: The Mediating Role of Behavioural Engagement and Brand Attachment" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 4: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040124

APA StyleAlFraihat, S. F. A., Ali, A. M., Hodaifa, G., & Alghizzawi, M. (2025). The Impact of Digital Content Marketing on Brand Defence: The Mediating Role of Behavioural Engagement and Brand Attachment. Administrative Sciences, 15(4), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15040124