Analyzing the Interconnection Between Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Criteria and Corporate Corruption: Revealing the Significant Impact of Greenwashing

Abstract

1. Introduction

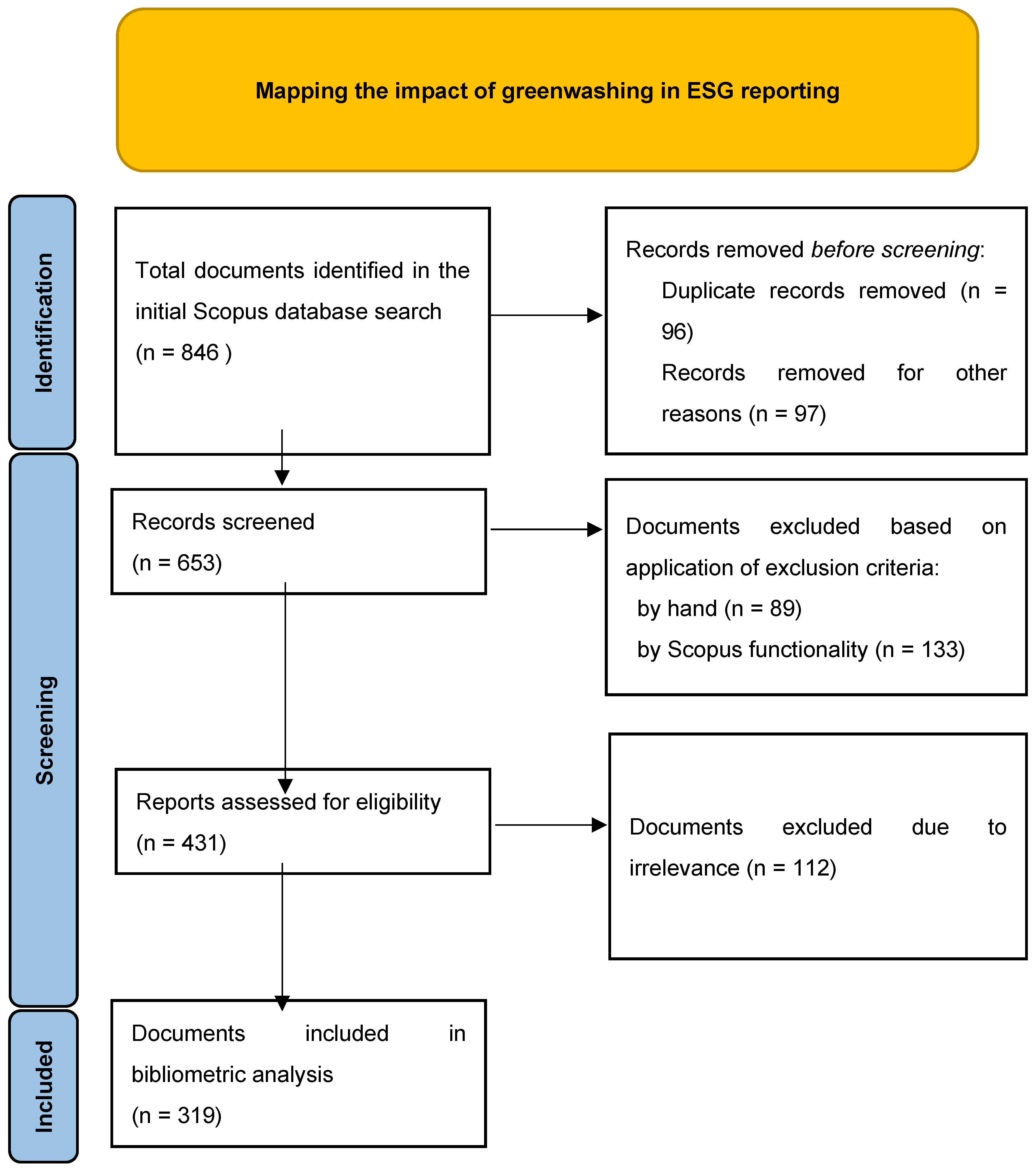

2. Greenwashing: A Type of Corruption That Impacts Climate Risk

3. Materials and Methods

Data

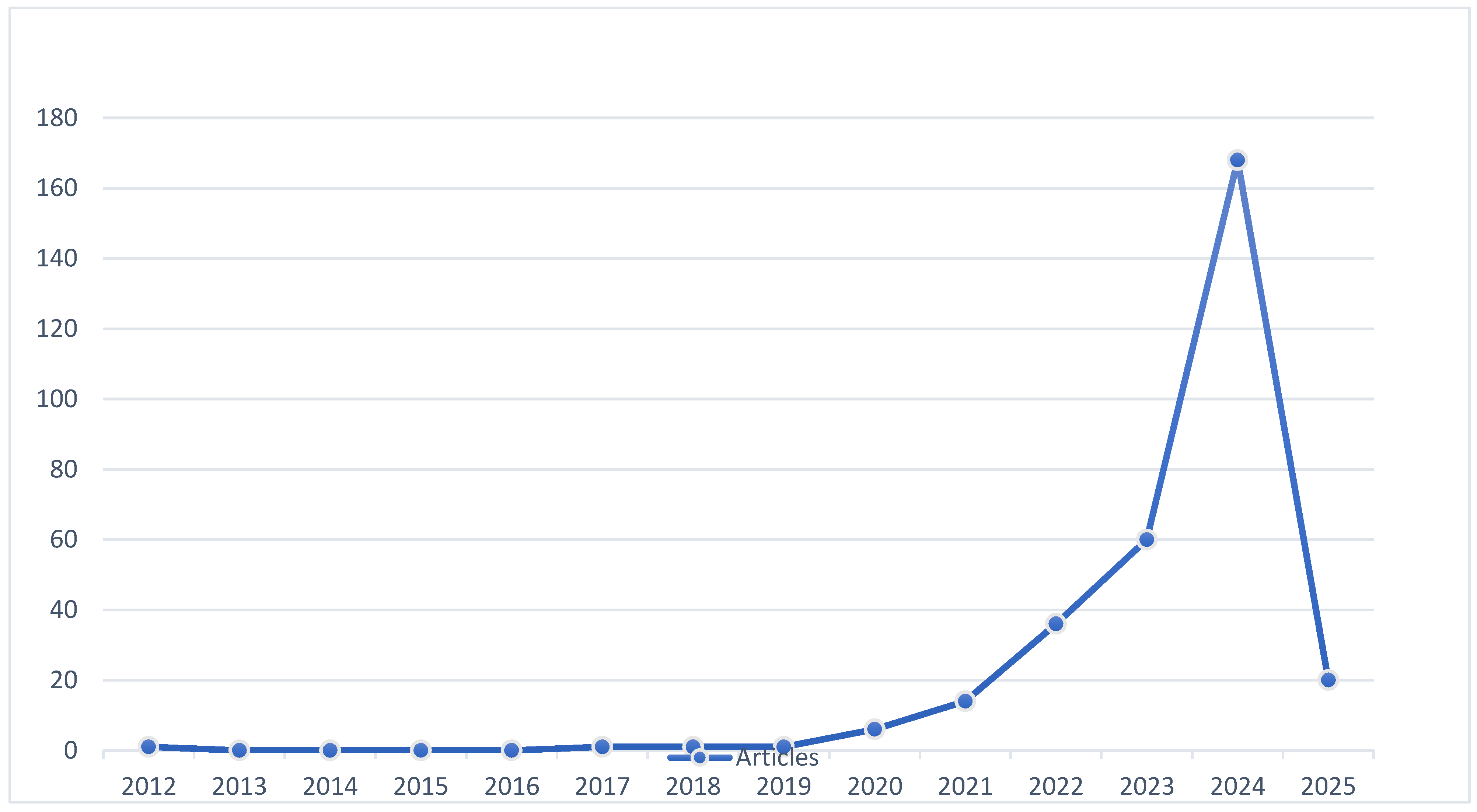

4. Results

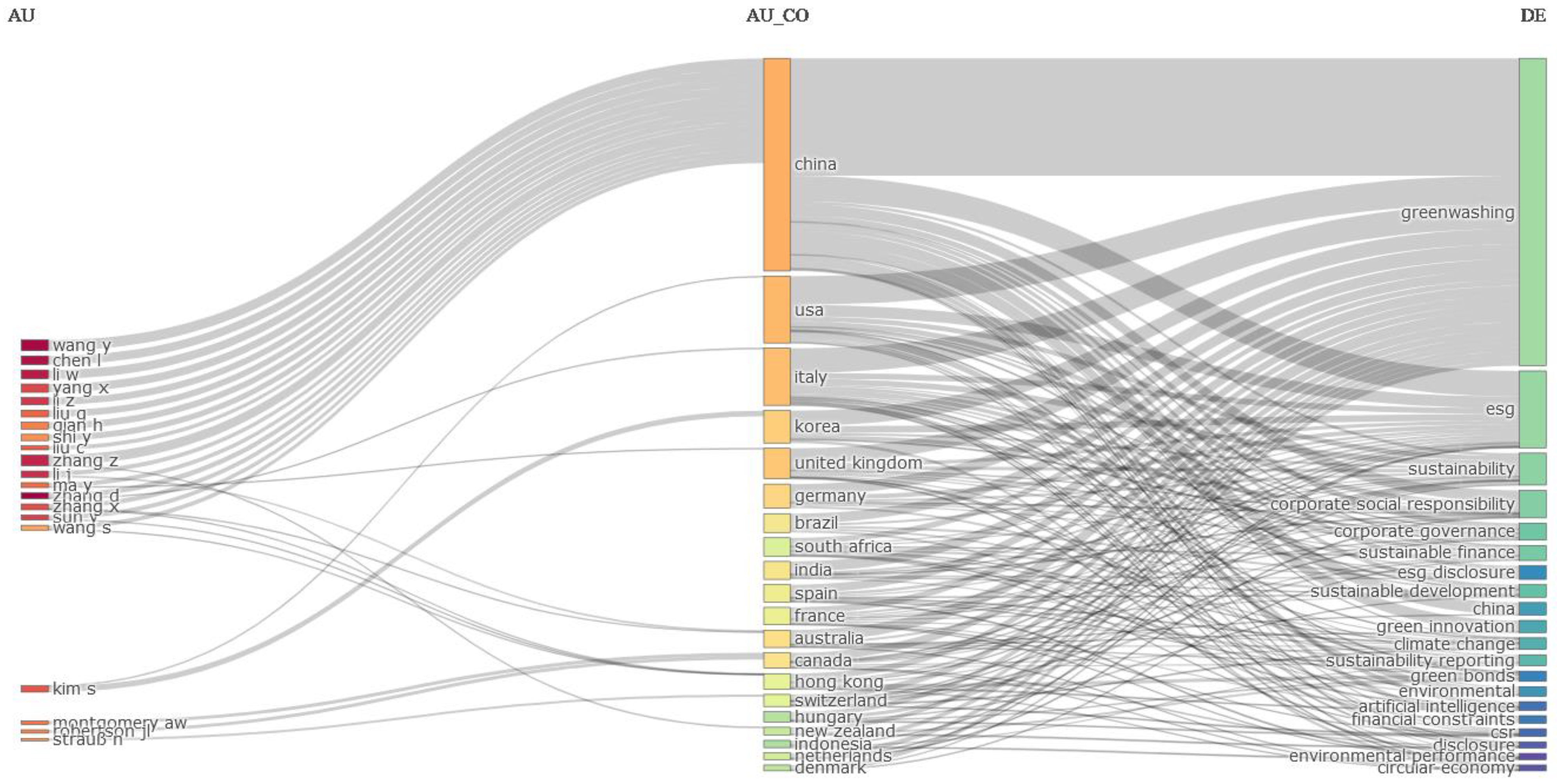

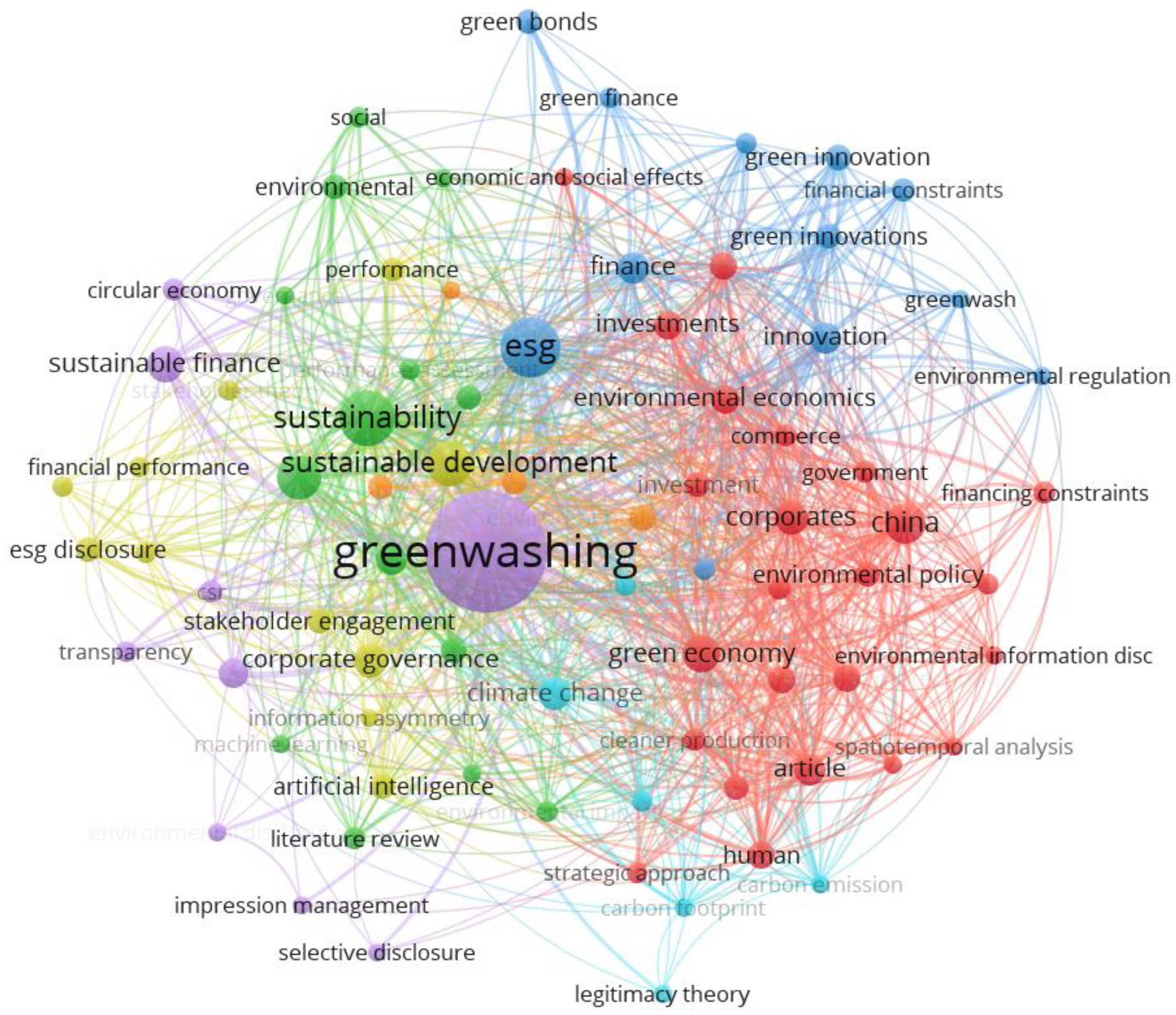

4.1. Network Analysis

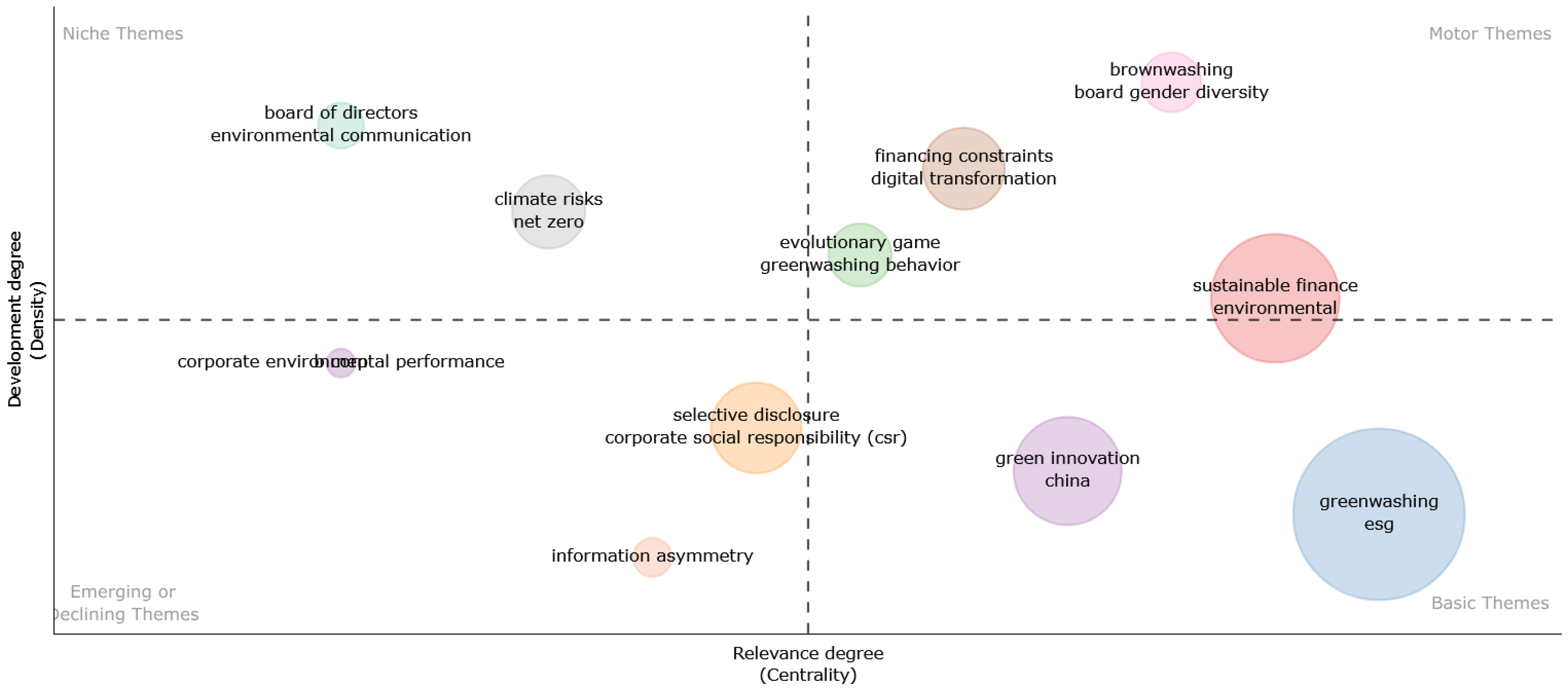

4.2. Bibliometric Analysis

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aronczyk, M., McCurdy, P., & Russill, C. (2024). Greenwashing, net-zero, and the oil sands in Canada: The case of Pathways Alliance. Energy Research and Social Science, 112, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, U. S., Tariq, A., Farrukh, M., Raza, A., & Iqbal, M. K. (2022). Green bonds for sustainable development: Review of literature on development and impact of green bonds. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birindelli, G., Chiappini, H., & Jalal, R. N. U. D. (2024). Greenwashing, bank financial performance and the moderating role of gender diversity. Research in International Business and Finance, 69, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, M., Busch, P., & Kendall, A. (2023). Life cycle assessment, quo vadis? Supporting or deterring greenwashing? A survey of practitioners. Environmental Science: Advances, 3(2), 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buertey, S., Sun, E. J., Lee, J. S., & Hwang, J. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and earnings management: The moderating effect of corporate governance mechanisms. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(1), 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. (2024). Does data assetisation improve corporate liquidity and corporate growth? Evidence from “hidden champion” SMEs in China. Borsa Istanbul Review, 24(6), 1205–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chueca Vergara, C., Ferruz Agudo, L., Rambaud, C., López Pascual, J., & Morley, B. (2021). Fintech and sustainability: Do they affect each other? Sustainability, 13(13), 7012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demers, E., Hendrikse, J., Joos, P., & Lev, B. (2021). ESG did not immunize stocks during the COVID-19 crisis, but investments in intangible assets did. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 48(3–4), 433–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H., Zhang, L., & Zheng, H. (2024). Green bonds: Fueling green innovation or just a fad? Energy Economics, 135, 107660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshabshiri, A., Ghanim, A., Hussien, A., Maksoud, A., & Mushtaha, E. (2025). Integration of Building Information Modeling and Digital Twins in the Operation and Maintenance of a building lifecycle: A bibliometric analysis review. Journal of Building Engineering, 99, 111541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, V. (2025). Corporate greenwashing and green management indicators. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators, 100599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, S., Mazzù, S., Naciti, V., & Paltrinieri, A. (2024). A PRISMA systematic review of greenwashing in the banking industry: A call for action. Research in International Business and Finance, 69, 102262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompers, P., Ishii, J., & Metrick, A. (2003). Corporate governance and equity prices. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 107–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T., John, K., Teng, H., & Wu, Q. (2023). Creative corporate culture and corporate tax avoidance. British Accounting Review, 56(3), 101217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Xiong, N., & Liu, C. K. (2024). Renewable energy technology innovation and ESG greenwashing: Evidence from supervised machine learning methods using patent text. Journal of Environmental Management, 370, 122833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C., Li, X., Xu, Q., & Liu, J. (2024). Does environmental protection tax impact corporate ESG greenwashing? A quasi-natural experiment in China. Economic Analysis and Policy, 84, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. U., Ma, Z., Li, M., Zhi, L., Hu, W., & Yang, X. (2023). From traditional to emerging technologies in supporting smart libraries. A bibliometric and thematic approach from 2013 to 2022. Library Hi Tech. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, T., & Denner, N. (2025). Different shades of green deception. Greenwashing’s adverse effects on corporate image and credibility. Public Relations Review, 51(1), 102521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koemtzopoulos, D., Zournatzidou, G., & Sariannidis, N. (2025). Can cryptocurrencies be green? The ROLE of stablecoins toward a carbon footprint and sustainable ecosystem. Sustainability, 17(2), 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashitew, A. A. (2021). Corporate uptake of the sustainable development goals: Mere greenwashing or an advent of institutional change? Journal of International Business Policy, 4(1), 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. T., & Raschke, R. L. (2023). Stakeholder legitimacy in firm greening and financial performance: What about greenwashing temptations? Journal of Business Research, 155, 113393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D., Zhang, Z., & Gao, X. (2024). Does artificial intelligence deter greenwashing? Finance Research Letters, 67, 105954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. (2024). Controlling shareholders’ stock pledges and greenwashing–Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters, 69, 106227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., & Chen, Q. (2024). Executive pay gap and corporate ESG greenwashing: Evidence from China. International Review of Financial Analysis, 95, 103375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Shi, C., Xiao, Z., & Zhang, X. (2024). Bridging the green gap: How digital financial inclusion affects corporate ESG greenwashing. Finance Research Letters, 69, 106018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Luo, T., Li, J., & Tian, Y. (2024a). Does social responsibility reform curb corporate greenwashing: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. International Review of Financial Analysis, 96, 103623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Miao, S., & Xu, L. (2024b). Digital transformation and environmental, social, and governance greenwashing: Evidence from China. Journal of Environmental Management, 365, 121460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Y., Lei, Q., Li, R., & Zhang, Y. J. (2024). Resistance or motivation? Impact of climate risk on corporate greenwashing: An empirical study of Chinese enterprises. Global Finance Journal, 62, 101030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Wang, C., & Wang, X. (2025). Greenwashing and corporate market power. Journal of Cleaner Production, 486, 144486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C., Chishti, M. F., Durrani, M. K., Bashir, R., Safdar, S., & Hussain, R. T. (2023). The corporate social responsibility and its impact on financial performance: A case of developing countries. Sustainability, 15(4), 3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., & Ahmad, M. I. (2024). Do board characteristics impact greenwashing? Moderating role of CSR committee. Heliyon, 10(20), e38743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliorelli, M. (2021). What do we mean by sustainable finance? assessing existing frameworks and policy risks. Sustainability, 13(2), 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J., Sigurjonsson, T. O., Kavadis, N., & Wendt, S. (2024). Green bonds and sustainable business models in Nordic energy companies. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, 7, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K. S., Serret, V., & Urom, C. (2024). The effect of green bonds on climate risk amid economic and environmental policy uncertainties. Finance Research Letters, 62, 105099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodaley, W., & Telukdarie, A. (2023). Greenwashing, sustainability reporting, and artificial intelligence: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 15(2), 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., Stewart, L. A., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, D., & Kong, Q. (2024). Corporate green innovation under environmental regulation: The role of ESG ratings and greenwashing. Energy Economics, 140, 107971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q., & Xie, Y. (2024). ESG greenwashing and corporate debt financing costs. Finance Research Letters, 69, 106012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazou, K., Zournatzidou, G., Sklavos, G., & Sariannidis, N. (2024). Integration of circular economy and urban metabolism for a resilient waste-based sustainable urban environment. Urban Science, 8(4), 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvetsova, O. A., & Lee, S. K. (2021). Living labs in university-industry cooperation as a part of innovation ecosystem: Case study of South Korea. Sustainability, 13(11), 5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. C., Mateos, A. C., Due, A. S., Bergström, J., Nordentoft, M., Clemmensen, L., & Glenthøj, L. B. (2024). Immersive virtual reality in the treatment of auditory hallucinations: A PRISMA scoping review. Psychiatry Research, 334, 115834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Y., Lau, Y. W., & Binti Ngalim, S. M. (2024). Do pilot zones for green finance reform and innovation avoid ESG greenwashing? Evidence from China. Heliyon, 10(13), E33710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyar, A., Karaman, A. S., & Kilic, M. (2020). Is corporate social responsibility reporting a tool of signaling or greenwashing? Evidence from the worldwide logistics sector. Journal of Cleaner Production, 253, 119997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Ke, Y., Sun, L., & Liu, H. (2024). Speculative culture and corporate greenwashing: Evidence from China. International Review of Financial Analysis, 95, 103447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Hu, F., & Wang, Y. (2024a). Analyst coverage and greenwashing: Evidence from Chinese A-Share listed corporations. International Review of Economics and Finance, 94, 103423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Su, M., Shen, L., & Tang, R. (2021). Decision-making of closed-loop supply chain under corporate social responsibility and fairness concerns. Journal of Cleaner Production, 284, 125373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Tai, P., & Pang, M. (2024b). Corporate social responsibility and corporate fraud: The mediating effect of analyst attention. Finance Research Letters, 64, 105370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Hsieh, T. S., & Sarkis, J. (2018). CSR performance and the readability of CSR Reports: Too good to be true? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(1), 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., & Sarkis, J. (2017). Corporate social responsibility governance, outcomes, and financial performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 162, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B., Jiang, K., & Santibanez Gonzalez, E. D. R. (2024). The coevolution effect of central bank digital currency and green bonds on the net-zero economy. Energy Economics, 134, 107587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E. P., Van Luu, B., & Chen, C. H. (2020). Greenwashing in environmental, social and governance disclosures. Research in International Business and Finance, 52, 101192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. (2022a). Are firms motivated to greenwash by financial constraints? Evidence from global firms’ data. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 33(3), 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. (2022b). Green financial system regulation shock and greenwashing behaviors: Evidence from Chinese firms. Energy Economics, 111, 106064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Huang, X., Liu, F., & Pan, L. (2024). Executive power discrepancy and corporate ESG greenwashing. International Review of Financial Analysis, 96, 103533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zournatzidou, G. (2024). Evaluating executives and non-executives’ impact toward esg performance in banking sector: An entropy weight and TOPSIS method. Administrative Sciences, 14(10), 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zournatzidou, G., Sklavos, G., Ragazou, K., & Sariannidis, N. (2024). Anti-competition and anti-corruption controversies in the european financial sector: Examining the Anti-ESG factors with entropy weight and TOPSIS methods. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(11), 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Keyword Search |

|---|---|

| 1 | ((“corruption” AND “ESG”)) |

| 2 | ((“corruption” OR “fraud”) AND “ESG”)) |

| 3 | ((“corruption” OR “fraud” OR “controversies”) AND “ESG”)) |

| 4 | ((“corruption” OR “fraud” OR “controversies”) AND (“corporate washing”) AND “ESG”)) |

| 5 | ((“corruption” OR “fraud” OR “controversies”) AND (“corporate washing” OR “greenwashing”) AND “ESG”)) |

| 6 | ((“corruption” OR “fraud” OR “controversies”) AND (“corporate washing” OR “greenwashing” OR “bluewashing”) AND “ESG”)) |

| 7 | ((“corruption” OR “fraud” OR “controversies” OR “money laundering”) AND (“corporate washing” OR “greenwashing” OR “bluewashing”) AND “ESG”)) |

| 8 | ((“corruption” OR “fraud” OR “controversies” OR “money laundering”) AND (“corporate washing” OR “greenwashing” OR “bluewashing” OR “pinkwashing”) AND “ESG”)) |

| 9 | ((“corruption” OR “fraud” OR “controversies” OR “money laundering”) AND (“corporate washing” OR “greenwashing” OR “bluewashing” OR “pinkwashing”) AND (“ESG” OR “sustainability” OR “sustainable development” OR “circular economy”) AND (“climate risk”)) |

| 10 | ((“corruption” OR “fraud” OR “controversies” OR “money laundering”) AND (“corporate washing” OR “greenwashing” OR “bluewashing” OR “pinkwashing”) AND (“ESG” OR “sustainability” OR “sustainable development” OR “circular economy”) AND (“climate risk”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE, “final”) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE, “aip”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SRCTYPE, “j”)) |

| Paper | Total Citations | TCs per Year | Normalized TCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greenwashing in environmental, social and governance disclosures (Yu et al., 2020) | 405 | 67.50 | 3.38 |

| Corporate social responsibility governance, outcomes, and financial performance (Z. Wang & Sarkis, 2017) | 388 | 43.11 | 1.00 |

| CSR Performance and the Readability of CSR Reports: Too Good to be True? (Z. Wang et al., 2018) | 230 | 28.75 | 1.00 |

| ESG did not immunize stocks during the COVID-19 crisis, but investments in intangible assets did (Demers et al., 2021) | 211 | 42.20 | 4.81 |

| Is corporate social responsibility reporting a tool of signaling or greenwashing? Evidence from the worldwide logistics sector (Uyar et al., 2020) | 159 | 26.50 | 1.33 |

| Green financial system regulation shock and greenwashing behaviors: Evidence from Chinese firms (Zhang, 2022b) | 155 | 38.75 | 4.63 |

| Stakeholder legitimacy in firm greening and financial performance: What about greenwashing temptations? (Lee & Raschke, 2023) | 134 | 44.67 | 6.31 |

| Are firms motivated to greenwash by financial constraints? Evidence from global firms’ data (Zhang, 2022a) | 119 | 29.75 | 3.55 |

| What Do We Mean by Sustainable Finance? Assessing Existing Frameworks and Policy Risks (Migliorelli, 2021) | 102 | 20.40 | 2.33 |

| Corporate uptake of the Sustainable Development Goals: Mere greenwashing or an advent of institutional change? (Lashitew, 2021) | 100 | 20.00 | 2.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poiriazi, E.; Zournatzidou, G.; Konteos, G.; Sariannidis, N. Analyzing the Interconnection Between Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Criteria and Corporate Corruption: Revealing the Significant Impact of Greenwashing. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030100

Poiriazi E, Zournatzidou G, Konteos G, Sariannidis N. Analyzing the Interconnection Between Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Criteria and Corporate Corruption: Revealing the Significant Impact of Greenwashing. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(3):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030100

Chicago/Turabian StylePoiriazi, Eleni, Georgia Zournatzidou, George Konteos, and Nikolaos Sariannidis. 2025. "Analyzing the Interconnection Between Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Criteria and Corporate Corruption: Revealing the Significant Impact of Greenwashing" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 3: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030100

APA StylePoiriazi, E., Zournatzidou, G., Konteos, G., & Sariannidis, N. (2025). Analyzing the Interconnection Between Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Criteria and Corporate Corruption: Revealing the Significant Impact of Greenwashing. Administrative Sciences, 15(3), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030100