Servant Leadership Style and Employee Voice: Mediation via Trust in Leaders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Servant Leadership Style

2.2. Characteristics of Servant Leadership

2.3. Prosocial Voice

2.4. Defensive Voice

2.5. Acquiescent Voice

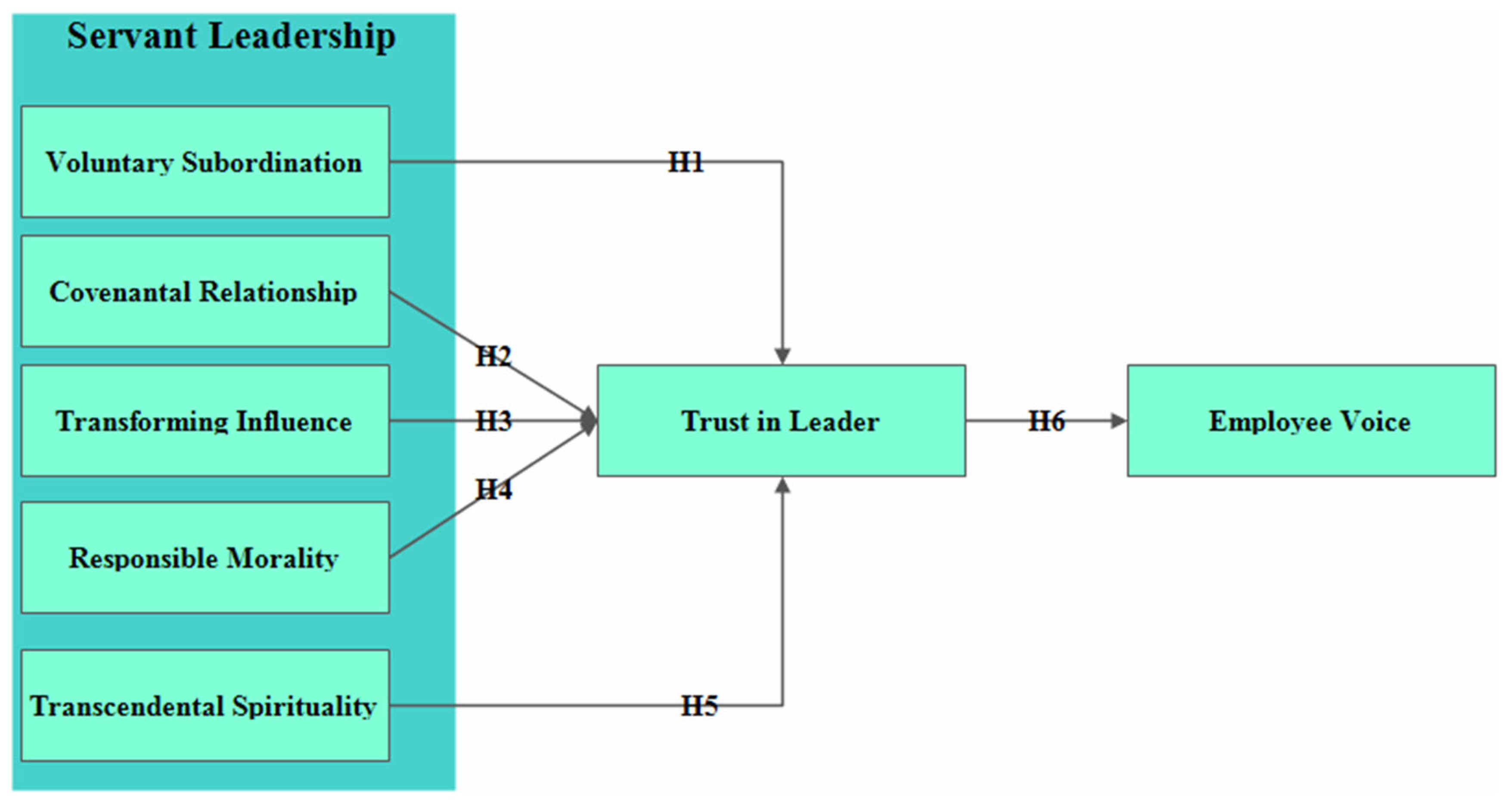

3. Research Modeland Hypothesis Development

3.1. Voluntary Subordination

3.1.1. Covenantal Leadership

3.1.2. Transforming Influence

3.1.3. Responsible Morality

3.1.4. Transcendental Spirituality

3.2. Mediating Role of Trust in Leader

4. Methods

Population and Sampling

5. Analysis and Results

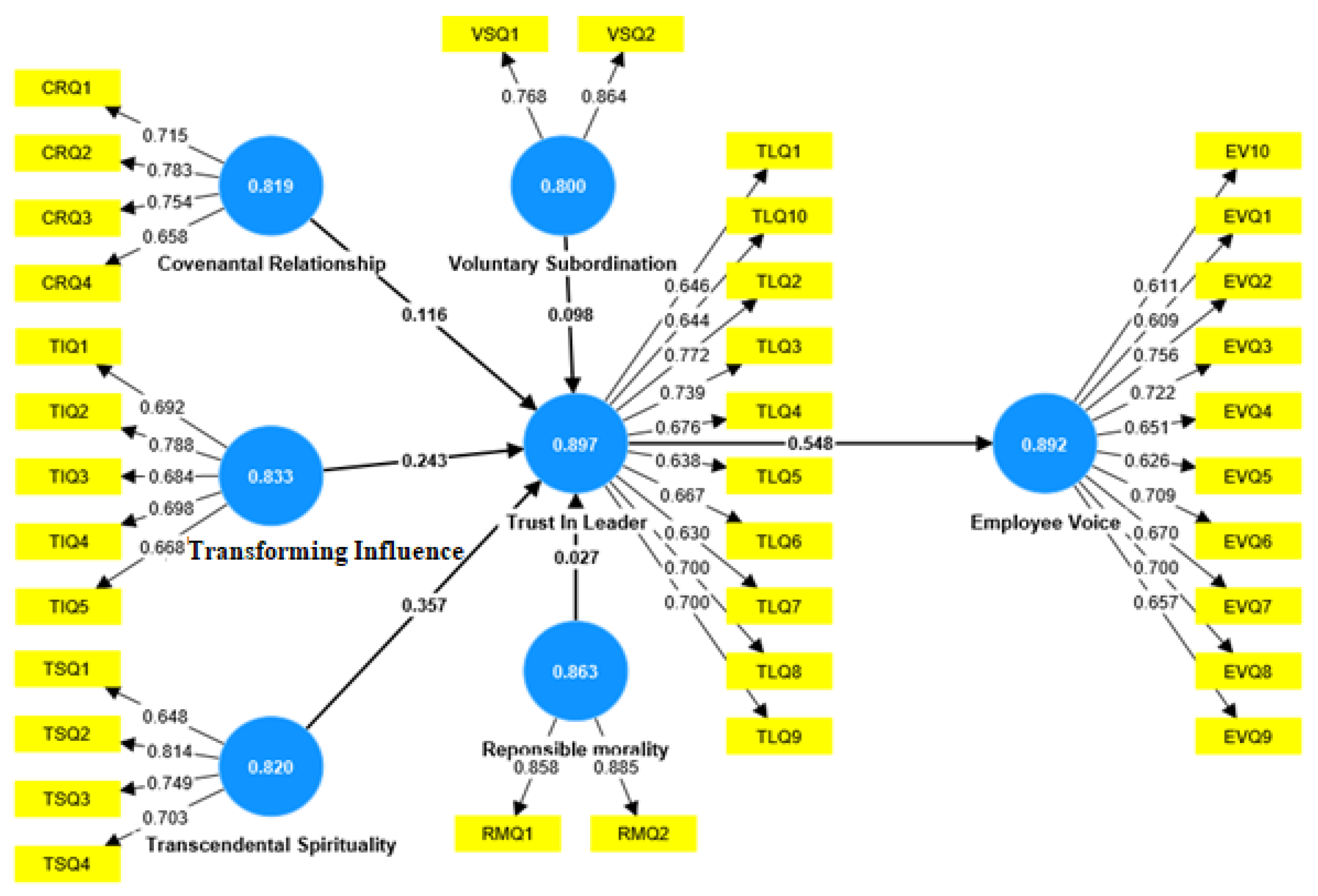

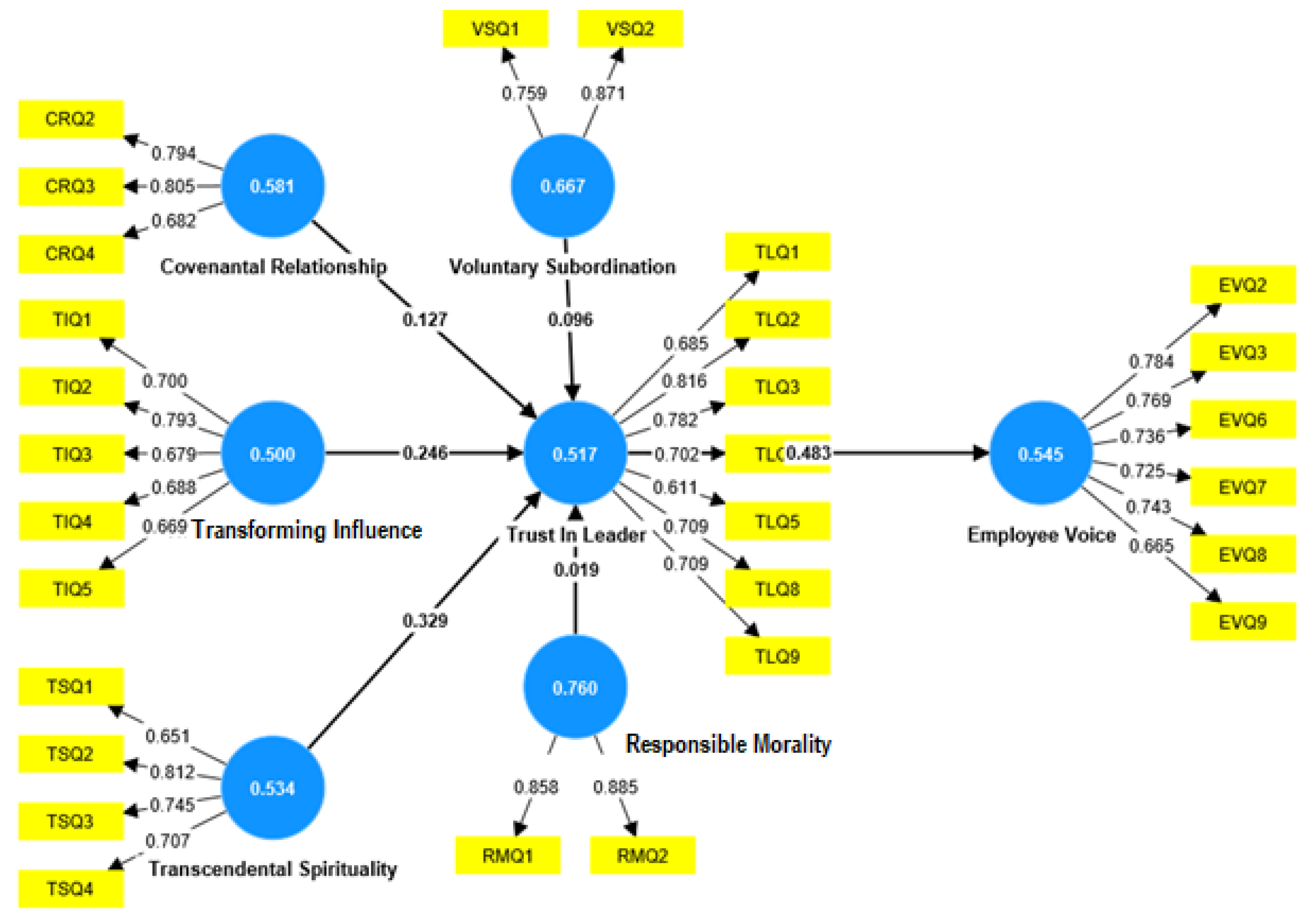

5.1. Assessment of Measurement Model

5.1.1. Reliability of the Measurement Model

5.1.2. Model Validity

5.2. The Predictive Validity

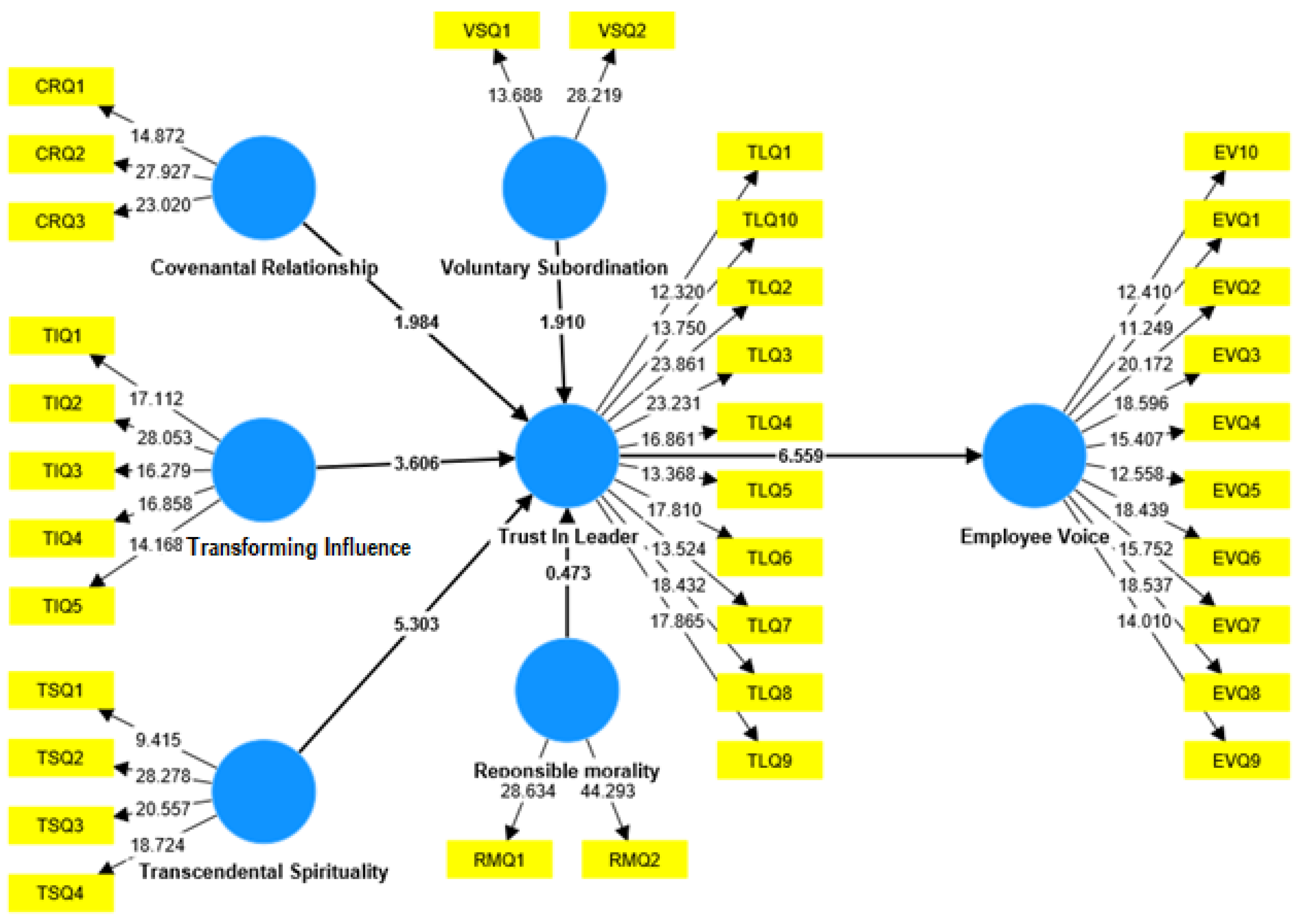

5.3. Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussion

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aarum Andersen, J. (2009). When a servant-leader comes knocking…. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 30, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Afthanorhan, A., Awang, Z., & Aimran, N. (2020). An extensive comparison of CB-SEM and PLS-SEM for reliability and validity. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 4, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwale, O. E. (2019). Employee voice: Speaking up in organisation as a correlate of employee productivity in oil and gas industry: An empirical investigation from Nigeria. Serbian Journal of Management, 14, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F., Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Ryu, K. (2018). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansoori, M. T. S., Rahman, I. A., Memon, A. H., & Nasaruddin, N. A. N. (2021). Structural Relationship of Factors Affecting PMO Implementation in the Construction Industry. Civil Engineering Journal, 7, 2109–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A., & Ahmadi Zahrani, M. (2020). The Impact Strategic-Servant Leadership on Employee Voice and Job Involvement Considering the Moderating and Mediating Role of Organizational Identity. Organizational Behaviour Studies Quarterly, 9, 219–248. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M. (2017). Transformational leadership in education: A review of existing literature. International Social Science Review, 93, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Asencio, H., & Mujkic, E. (2016). Leadership behaviors and trust in leaders: Evidence from the US federal government. Public Administration Quarterly, 40, 156–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B. J., & Svensson, G. (2012). Structural equation modeling in social science research: Issues of validity and reliability in the research process. European Business Review, 24, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M., & Wilkinson, A. (2016). Pro-social or pro-management? A critique of the conception of employee voice as a pro-social behaviour within organizational behaviour. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 54, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, F., Mohammad, J., & Awang, S. R. (2021). The effect of servant leadership on organisational sustainability: The parallel mediation role of creativity and psychological resilience. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 43, 71–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bavik, A., Bavik, Y. L., & Tang, P. M. (2017). Servant leadership, employee job crafting, and citizenship behaviors: A cross-level investigation. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 58, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, K. (2003). Servant leader. Thomas Nelson. [Google Scholar]

- Boyum, V. S. (2012). A model of servant leadership in higher education. University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Brinsfield, C. T., & Edwards, M. S. (2020). Employee voice and silence in organizational behavior. In Handbook of research on employee voice. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bucci, J., & Lewis, P. W. (2016). The case for inclusion of redemptive managerial dimensions in servant leadership theory. Journal of Biblical Integration in Business, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callen, M., Gulzar, S., Hasanain, A., Yasir Khan, M., & Rezaee, A. (2022). Personalities and public sector performance: Experimental evidence from pakistan. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cansoy, R., & Parlar, H. (2018). Examining the relationship between school principals’ instructional leadership behaviors, teacher self-efficacy, and collective teacher efficacy. International Journal of Educational Management, 32, 550–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S. E., Kim, S. S., Hewlin, P. F., & DeRue, D. S. (2020). Turning a blind or critical eye to leader value breaches: The role of value congruence in employee perceptions of leader integrity. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 27, 286–306. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S. C., & Mak, W.-M. (2014). The impact of servant leadership and subordinates’ organizational tenure on trust in leader and attitudes. Personnel Review, 43, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, N. (2018). Barriers and facilitators of growth in black entrepreneurial ventures: Thinking outside the black box. Case Western Reserve University. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs. PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, D. J. (2022). Development of an Inclusive Leadership Theory Rooted in Respect for Human Dignity. In Leading with diversity, equity and inclusion (pp. 105–120). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Delecta, P. (2011). Work life balance. International Journal of Current Research, 3, 186–189. [Google Scholar]

- Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management journal, 50, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolittle, J. S. (2021). The Value of Servant-leadership in Sodexo. Editorial Board, 2021, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J., Xu, Y., Wang, X., Wu, C.-H., & Wang, Y. (2021). Voice for oneself: Self-interested voice and its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 94, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S., & Khatri, P. (2017). Servant leadership and positive organizational behaviour: The road ahead to reduce employees’ turnover intentions. On the Horizon, 25(1), 60–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, T., Anjum, Z. U. Z., Rasheed, M., Waqas, M., & Hameed, A. A. (2022). Impact of ethical leadership on employee well-being: The mediating role of job satisfaction and employee voice. Middle East Journal of Management, 9, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., Van Dierendonck, D., & Liden, R. C. (2019). Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. The Leadership Quarterly, 30, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, M., Men, L. R., & O’Neil, J. (2019). Using social media to engage employees: Insights from internal communication managers. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13, 110–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairholm, M. R., & Gronau, T. W. (2015). Spiritual leadership in the work of public administrators. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 12, 354–373. [Google Scholar]

- Ficapal-Cusí, P., Enache-Zegheru, M., & Torrent-Sellens, J. (2020). Linking perceived organizational support, affective commitment, and knowledge sharing with prosocial organizational behavior of altruism and civic virtue. Sustainability, 12, 10289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M., & Antunes, A. (2020). Understanding servant leadership dimensions: Theoretical and empirical extensions in the Portuguese context. Nankai Business Review International, 11, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A. S., Koopman, J., Rosen, C. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2018). Helping others or helping oneself? An episodic examination of the behavioral consequences of helping at work. Personnel Psychology, 71, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, F., & Stone, S. (2018). Leadership, leadership styles, and servant leadership. Journal of Management Research, 18, 261–269. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L., Janssen, O., & Shi, K. (2011). Leader trust and employee voice: The moderating role of empowering leader behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Zhu, Y., & Zhang, L. (2020). Inclusive leadership, leader identification and employee voice behavior: The moderating role of power distance. Current Psychology, 41, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. S.-T., & Purohit, D. H. (2021). Digital advertisement and its impact on spirituality in leadership. Editorial Board, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Hafenbrack, A. C., Cameron, L. D., Spreitzer, G. M., Zhang, C., Noval, L. J., & Shaffakat, S. (2020). Helping people by being in the present: Mindfulness increases prosocial behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 159, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Matthews, L., Matthews, R., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N., Rhee, J., & Dedahanov, A. (2019). Organizational Culture Influences on Creativity and Inno vation: A Review. Global Political Review, 4, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing, in new challenges to international marketing. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Heyler, S. G., & Martin, J. A. (2018). Servant leadership theory: Opportunities for additional theoretical integration. Journal of Managerial Issues, 2018, 230–243. [Google Scholar]

- Hoch, J. E., Bommer, W. H., Dulebohn, J. H., & Wu, D. (2018). Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 44, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holley, E. C., Wu, K., & Avey, J. B. (2019). The impact of leader trustworthiness on employee voice and performance in China. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 26, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, J. N., Jacobson, K. J., & Van Buren, H. J., III. (2011). Creating ethical organisational cultures by managing the reactive and proactive workplace bully. International Journal of Economics and Business Research, 3, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiung, H.-H. (2012). Authentic leadership and employee voice behavior: A multi-level psychological process. Journal of Business Ethics, 107, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Shu, J., & Liu, C. (2018). Employee work performance mediates empowering leader behavior and employee voice. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 46, 1997–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, H., Zeeshan, F., & Waheed, A. (2012). SMEs development and failure avoidance in developing countries through public private partnership. African Journal of Business Management, 6, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M. (2019). Servant leadership, burnout, and turnover intention. In Servant leadership styles and strategic decision making (pp. 197–204). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, A., Latif, K. F., & Ahmad, M. S. (2020). Servant leadership and employee innovative behaviour: Exploring psychological pathways. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 41, 813–827. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, R. D. (2012). Servant or leader? Who will stand up please? International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3, 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Ja’afaru Bambale, A. (2014). Relationship between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behaviors: Review of literature and future research directions. Journal of Marketing & Management, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, N. K., & Dhar, R. L. (2017). The influence of servant leadership, trust in leader and thriving on employee creativity. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38, 2–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, R. (2014). Social identity. Milton: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaraj, J. J., & Gandolfi, F. (2019). Exploring trust, dialogue, and empowerment in servant leadership insights from critical pedagogy. Journal of Management Research, 19, 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, S. (2021). Employee voice behavior: A moderated mediation analysis of high-performance work system. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., Gao, A., & Yang, B. (2018). Employees’ critical thinking, leaders’ inspirational motivation, and voice behavior: The mediating role of voice efficacy. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkiewicz, C. L., & Giacalone, R. A. (2004). A values framework for measuring the impact of workplace spirituality on organizational performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 49, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkowsky, T. (2020). The secret sauce for organizational success: Communications and leadership on the same page. Air University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaludin, N. N. A., & Ismail, F. (2021). Maintain A Culture Of Integrity At Workplace During Covid-19 Outbreak. Jurnal Penyelidikan Sains Sosial (JOSSR), 4, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kaptein, M. (2008). Developing a measure of unethical behavior in the workplace: A stakeholder perspective. Journal of Management, 34, 978–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabati, S. (2021). Organizational outcomes of destructive leadership: Summary and evaluation. In Destructive leadership and management hypocrisy. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Katopol, P. F. (2015). Everybody wins: Servant-leadership. Library Leadership & Management, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (2015). The wisdom of teams: Creating the high-performance organization. Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M., Lee, H. Y., & Bae, J. H. (2019). The Role of Transparency in Humanitarian Logistics. Sustainability, 11, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M., Parvaiz, G. S., Ali, A., Jehangir, M., Hassan, N., & Bae, J. (2022a). A Model for Understanding the Mediating Association of Transparency between Emerging Technologies and Humanitarian Logistics Sustainability. Sustainability, 14, 6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M., Parvaiz, G. S., Dedahanov, A. T., Abdurazzakov, O. S., & Rakhmonov, D. A. (2022b). The Impact of Technologies of Traceability and Transparency in Supply Chains. Sustainability, 14, 16336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M., Sarmad, M., Ullah, S., & Bae, J. (2020). Education for sustainable development in humanitarian logistics. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 10, 573–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., Choi, L., Borchgrevink, C. P., Knutson, B., & Cha, J. (2018). Effects of Gen Y hotel employee’s voice and team-member exchange on satisfaction and affective commitment between the US and China. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30, 2230–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y., Wang, J., & Chen, J. (2018). Mutual trust between leader and subordinate and employee outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics, 149, 945–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koole, S. L., Van Dillen, L. F., & Sheppes, G. (2011). The self-regulation of emotion. Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications, 2, 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. (2018). Servant leadership: A review of literature. Pacific Business Review International, 11, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpikaitė-Valiūnienė, V. (2014). Spirituality at work: Comparison analysis. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 150, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, H., Palanski, M. E., & Simons, T. (2012). Authentic leadership and behavioral integrity as drivers of follower commitment and performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 107, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X., Chen, Z. X., Tse, H. H., Wei, W., & Ma, C. (2019). Why and when employees like to speak up more under humble leaders? The roles of personal sense of power and power distance. Journal of Business Ethics, 158, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. (2016). Does humble leadership behavior promote employees’ voice behavior?—A dual mediating model. Open Journal of Business and Management, 4, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Fuller, B., Hester, K., Bennett, R. J., & Dickerson, M. S. (2018). Linking authentic leadership to subordinate behaviors. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 39, 218–233. [Google Scholar]

- Mahembe, B., & Engelbrecht, A. S. (2013). A confirmatory factor analytical study of a servant leadership measure in South Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E. W., Wheeler-Smith, S. L., & Kamdar, D. (2011). Speaking up in groups: A cross-level study of group voice climate and voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niethammer, C., Saeed, T., Mohamed, S. S., & Charafi, Y. (2007). Women entrepreneurs and access to finance in pakistan. Women’s Policy Journal of Harvard, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nobari, E., Mohamadkhani, K., & Mohammad Davoudi, A. (2014). The relationship between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior of employees at valiasr academic complex, Islamic Azad University-Central Tehran Branch. International Journal of Management and Business Research, 4, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Okolie, U., & Idibra, M. P. (2021). Power misuse: An antecedent for workplace bullying. Journal Plus Education, 28, 110–124. [Google Scholar]

- Orabi, T. G. A. (2016). The impact of transformational leadership style on organizational performance: Evidence from Jordan. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 6, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, D. L., & Peachey, J. W. (2013). A systematic literature review of servant leadership theory in organizational contexts. Journal of Business Ethics, 113, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlow, L., & Williams, S. (2003). Is silence killing your company? IEEE Engineering Management Review, 31, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pohler, D., Luchak, A. A., & Harmer, J. (2020). The missing employee in employee voice research. In Handbook of research on employee voice. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Poulose, S., & Sudarsan, N. (2018). Work life balance: A conceptual review. International Journal of Advances in Agriculture Sciences, 5, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, S., & Dooley, L. (2022). How servant leadership affects organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating roles of perceived procedural justice and trust. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, I. A., & Gamil, Y. (2019). Assessment of cause and effect factors of poor communication in construction industry. In IOP Conference series: Materials science and engineering. IOP Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rego, A., Cunha, M. P. E., & Simpson, A. V. (2018). The perceived impact of leaders’ humility on team effectiveness: An empirical study. Journal of Business Ethics, 148, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushing, R. R. (2021). Servant leadership and psychological need satisfaction and frustration among healthcare leaders. Keiser University. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, R. F., & Stone, A. G. (2002). A review of servant leadership attributes: Developing a practical model. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 23, 145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Rutashobya, L., & Jaensson, J. E. (2004). Small firms’ internationalization for development in Tanzania: Exploring the network phenomenon. International Journal of Social Economics, 31, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankowsky, D. (1995). The charismatic leader as narcissist: Understanding the abuse of power. Organizational Dynamics, 23, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendjaya, S., & Pekerti, A. (2010). Servant leadership as antecedent of trust in organizations. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 31, 643–663. [Google Scholar]

- Sendjaya, S., Pekerti, A., Härtel, C., Hirst, G., & Butarbutar, I. (2016). Are authentic leaders always moral? The role of Machiavellianism in the relationship between authentic leadership and morality. Journal of Business Ethics, 133, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendjaya, S., Sarros, J. C., & Santora, J. C. (2008). Defining and measuring servant leadership behaviour in organizations. Journal of Management Studies, 45, 402–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, R. P. S. M., & Irawanto, S. D. W. (2020). Servant leadership characteristics, organisational commitment, followers’ trust, employees’ performance outcomes: A literature review. European Research Studies Journal, 23, 902–911. [Google Scholar]

- Seto, S., & Sarros, J. C. (2016). Servant Leadership Influence on Trust and Quality Relationship in Organizational Settings. International Leadership Journal, 8, 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, K. B. (2002). Toward a typology of Internet users and online privacy concerns. The Information Society, 18(1), 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Tian, Q.-T., & Kwan, H. K. (2022). Servant leadership and employee voice: A moderated mediation. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedham, Y., & Skaar, T. B. (2019). Mindfulness, trust, and leader effectiveness: A conceptual framework. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steger, M. F., Littman-Ovadia, H., Miller, M., Menger, L., & Rothmann, S. (2013). Engaging in work even when it is meaningless: Positive affective disposition and meaningful work interact in relation to work engagement. Journal of Career Assessment, 21, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambunan, T. T. H. (2011). Development of small and medium enterprises in a developing country: The Indonesian case. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 5, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thebo, J. A., Shah, Q. A., Shah, J. A., Shah, I. A., Soomro, H. J., & Khaskheli, G. A. (2021). Impact of Transformational Leadership Style On Job Performance, Job Satisfaction And Organizational Learning. Multicultural Education, 7, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Umair, M., & Ullah, R. (2013). Impact of GDP and inflation on unemployment rate: A study of Pakistan economy in 2000–2010. International Review of Management and Business Research, 2, 388. [Google Scholar]

- Unler, E., & Caliskan, S. (2019). Individual and managerial predictors of the different forms of employee voice. Journal of Management Development, 38, 582–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bos, K., Wilke, H. A., & Lind, E. A. (1998). When do we need procedural fairness? The role of trust in authority. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 75, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, C. M., Brady, M. K., Calantone, R., & Ramirez, E. (2016). Discriminant validity testing in marketing: An analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsen, E., & Blind, K. (2016). More labour market flexibility for more innovation? Evidence from employer–employee linked micro data. Research Policy, 45, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F. O., & Schaubroeck, J. (2009). Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.-S., & Hsieh, C.-C. (2013). The effect of authentic leadership on employee trust and employee engagement. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 41, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A., & Fay, C. (2011). New times for employee voice? Human Resource Management, 50, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, B., & Fields, D. (2015). Seeking and measuring the essential behaviors of servant leadership. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 36, 413–434. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K. K.-K. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Marketing Bulletin, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S. I., & Kuvaas, B. (2018). The empowerment expectation–perception gap: An examination of three alternative models. Human Resource Management Journal, 28, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, B. (2018). Relationship between servant leadership attributes and trust in leaders: A case of sport instructors in South Korea. The Sport Journal, 21, 11–298. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.-Z., Tse, E. C.-Y., Fu, P., & Kwan, H. K. (2013). The impact of servant leadership on hotel employees “servant behavior”. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L. (2020). The impact of servant leadership and transformational leadership on learning organization: A comparative analysis. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 41(2), 220–236. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q., Chen, J., Chen, L., Jin, L., & Lou, D. (2008, December8–11). Total innovation management competence and innovation performance in SMEs.—An empirical study based on SME survey in Zhejiang Province. 2008 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, A., & Xiao, Y. (2016). Servant leadership and employee voice behavior: A cross-level investigation in China. SpringerPlus, 5, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğit, B., & Bozkurt, S. (2017). A content analysis of servant leadership studies. International Journal of Organizational Leadership, 6, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, D. T., Sendjaya, S., Hirst, G., & Cooper, B. (2014). Does servant leadership foster creativity and innovation? A multi-level mediation study of identification and prototypicality. Journal of Business Research, 67, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia-ur-Rehman, M., Shahbaz, A., & Hassan, N. (2018). Due Economy is Based on Authenticity? Authentic Leader’s Personality and Employees’ Voice Behaviour. Global Economics Review, 3, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | Freq | Qualification | Freq | Tenure | Freq | Designation | Freq | Tenure with Current Leader | Freq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–29 | 79 | Intermediate | 2 | 0–1 | 24 | CFO | 32 | 0–1 | 58 |

| 30–39 | 171 | Bachelor (BS) | 54 | 2–3 | 73 | HR Officer | 66 | 2–3 | 118 |

| 40–49 | 73 | Master | 259 | 4–5 | 156 | IT Officer | 74 | 4–5 | 111 |

| 50–59 | 13 | PhD | 21 | 6–7 | 83 | Marketing Officer | 65 | 6–7 | 49 |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | Director | 65 | ||

| - | - | - | - | - | - | Internee | 34 | ||

| Total | 336 | 336 | 336 | 336 | 336 |

| VS | CR | TI | RM | TS | TL | EV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 2.850 | 2.850 | 2.980 | 2.730 | 3.050 | 2.890 | 2.900 |

| Median | 2.800 | 2.800 | 2.920 | 2.730 | 3.060 | 2.880 | 2.900 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.599 | 0.599 | 0.781 | 0.578 | 0.676 | 0.618 | 0.628 |

| Variance | 0.358 | 0.358 | 0.610 | 0.334 | 0.457 | 0.382 | 0.395 |

| Skewness | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.059 | 0.082 | 0.062 | 0.066 | 0.071 |

| Std. Error of Skewness | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Kurtosis | −0.948 | −0.948 | −1.055 | −0.702 | −0.722 | −0.879 | −0.834 |

| Std. Error of Kurtosis | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.234 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| VIF | 1.64 | 1.79 | 1.56 | 1.62 | 2.19 | 1.62 | 1.94 |

| R2 | Adjusted R2 | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voluntary Subordination | 0.51 | 0.80 | 0.66 | ||

| Covenantal Relationship | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.58 | ||

| Transforming Influence | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.50 | ||

| Responsible Morality | 0.68 | 0.86 | 0.76 | ||

| Transcendental Spirituality | 0.71 | 0.82 | 0.53 | ||

| Trust in Leader | 0.513 | 0.506 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.51 |

| Employee voice | 0.301 | 0.299 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.54 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Covenantal Relationship | 0.73 | ||||||

| 2. Employee voice | 0.46 | 0.67 | |||||

| 3. Responsible Morality | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.87 | ||||

| 4. Transcendental Spirituality | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.73 | |||

| 5. Transforming Influence | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.707 | ||

| 6. Trust in Leader | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.66 | 0.638 | 0.68 | |

| 7. Voluntary Subordination | 0.59 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.505 | 0.47 | 0.82 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Covenantal Relationship_ | 1.000 | ||||||

| 2.Employee voice_ | 0.587 | 1.000 | |||||

| 3.Responsible Morality_ | 0.688 | 0.550 | 1.000 | ||||

| 4.Transcendental Spirituality_ | 0.829 | 0.657 | 0.792 | 1.000 | |||

| 5.Transforming Influence_ | 0.921 | 0.650 | 0.805 | 0.970 | 1.000 | ||

| 6.Trust in Leader | 0.707 | 0.624 | 0.598 | 0.834 | 0.788 | 1.000 | |

| 7.Voluntary Subordination_ | 0.982 | 0.608 | 0.783 | 0.795 | 0.809 | 0.700 | 1.000 |

| Saturated Model | Estimated Model | |

|---|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.064 | 0.075 |

| d_ULS | 2.867 | 3.969 |

| d_G | 1.009 | 1.029 |

| Chi-Square | 1882.641 | 1912.560 |

| NFI | 0.665 | 0.659 |

| SSO | SSE | Q2 (=1-SSE/SSO) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voluntary Subordination | 672.000 | 672.000 | |

| Covenantal Relationship | 1344.000 | 1344.000 | |

| Transforming Influence | 1680.000 | 1680.000 | |

| Responsible Morality | 672.000 | 672.000 | |

| Transcendental Spirituality | 1344.000 | 1344.000 | |

| Trust in Leader | 3360.000 | 2643.802 | 0.213 |

| Employee voice | 3360.000 | 2935.947 | 0.126 |

| Path Coefficient | Mean | Std. Dev. | t-Values | p-Values | Supported? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voluntary Subordination -> Trust in Leader (H1) | 0.103 | 0.109 | 0.054 | 1.918 | 0.056 | No |

| Covenantal Relationship -> Trust in Leader (H2) | 0.116 | 0.124 | 0.059 | 1.986 | 0.050 | Yes |

| Transforming Influence -> Trust in Leader (H3) | 0.244 | 0.240 | 0.071 | 3.606 | 0.001 | Yes |

| Responsible Morality -> Trust in Leader (H4) | 0.024 | 0.021 | 0.049 | 0.473 | 0.623 | No |

| Transcendental Spirituality -> Trust in Leader (H5) | 0.359 | 0.353 | 0.067 | 5.303 | 0.000 | Yes |

| Trust in Leader -> Employee Voice (H6) | 0.548 | 0.553 | 0.082 | 6.559 | 0.000 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hassan, N.; Yoon, J.; Dedahanov, A.T. Servant Leadership Style and Employee Voice: Mediation via Trust in Leaders. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030099

Hassan N, Yoon J, Dedahanov AT. Servant Leadership Style and Employee Voice: Mediation via Trust in Leaders. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(3):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030099

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassan, Noor, Junghyun Yoon, and Alisher Tohirovich Dedahanov. 2025. "Servant Leadership Style and Employee Voice: Mediation via Trust in Leaders" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 3: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030099

APA StyleHassan, N., Yoon, J., & Dedahanov, A. T. (2025). Servant Leadership Style and Employee Voice: Mediation via Trust in Leaders. Administrative Sciences, 15(3), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15030099