Evaluating Executives and Non-Executives’ Impact toward ESG Performance in Banking Sector: An Entropy Weight and TOPSIS Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Banking Practices in the EU: Shaping the Future of Finance

2.2. The Power of Independent Executives: The Bottom-Up Corporate Governance Approach

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Entropy Weight Method

3.3. TOPSIS Method

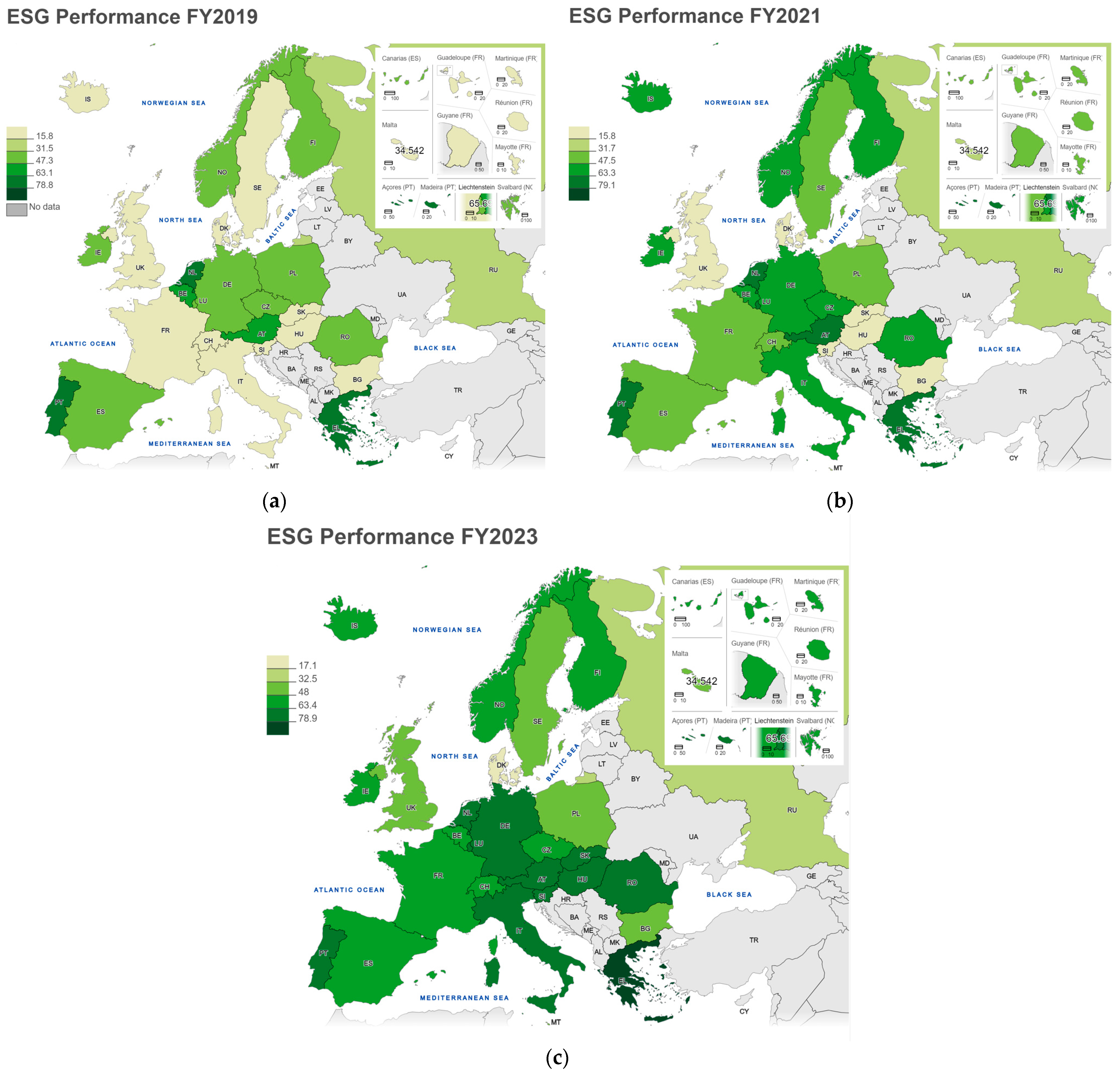

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.150 | 0.000 | 0.035 | 0.027 | 0.127 | 0.000 |

| 0.170 | 0.000 | 0.035 | 0.136 | 0.093 | 0.000 |

| 0.000 | 0.114 | 0.077 | 0.154 | 0.146 | 0.000 |

| 0.022 | 0.125 | 0.143 | 0.125 | 0.089 | 0.000 |

| 0.000 | 0.124 | 0.157 | 0.155 | 0.146 | 0.156 |

| 0.123 | 0.000 | 0.081 | 0.124 | 0.136 | 0.000 |

| 0.126 | 0.000 | 0.135 | 0.121 | 0.067 | 0.000 |

| 0.169 | 0.132 | 0.052 | 0.010 | 0.070 | 0.000 |

| 0.161 | 0.158 | 0.010 | 0.100 | 0.097 | 0.171 |

| 0.000 | 0.114 | 0.031 | 0.154 | 0.146 | 0.181 |

| 0.122 | 0.144 | 0.058 | 0.119 | 0.128 | 0.000 |

| 0.045 | 0.000 | 0.121 | 0.027 | 0.026 | 0.002 |

| 0.133 | 0.000 | 0.140 | 0.136 | 0.133 | 0.000 |

| 0.020 | 0.000 | 0.159 | 0.014 | 0.108 | 0.000 |

| 0.133 | 0.114 | 0.091 | 0.105 | 0.048 | 0.112 |

| 0.103 | 0.142 | 0.004 | 0.150 | 0.146 | 0.174 |

| 0.031 | 0.124 | 0.004 | 0.052 | 0.090 | 0.145 |

| 0.000 | 0.114 | 0.137 | 0.154 | 0.104 | 0.118 |

| 0.167 | 0.000 | 0.187 | 0.063 | 0.105 | 0.077 |

| 0.141 | 0.159 | 0.115 | 0.124 | 0.096 | 0.093 |

| 0.066 | 0.124 | 0.116 | 0.155 | 0.146 | 0.169 |

| 0.095 | 0.000 | 0.175 | 0.008 | 0.069 | 0.074 |

| 0.000 | 0.114 | 0.184 | 0.154 | 0.146 | 0.173 |

| 0.052 | 0.000 | 0.094 | 0.004 | 0.068 | 0.000 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.092 | 0.154 | 0.146 | 0.156 |

| 0.111 | 0.000 | 0.160 | 0.148 | 0.085 | 0.000 |

| 0.000 | 0.114 | 0.029 | 0.154 | 0.115 | 0.000 |

| 0.020 | 0.162 | 0.162 | 0.041 | 0.044 | 0.000 |

| 0.045 | 0.159 | 0.049 | 0.124 | 0.136 | 0.181 |

| 0.146 | 0.124 | 0.036 | 0.131 | 0.133 | 0.173 |

| 0.045 | 0.155 | 0.155 | 0.041 | 0.038 | 0.002 |

| 0.173 | 0.000 | 0.107 | 0.014 | 0.026 | 0.074 |

| 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.171 | 0.011 | 0.077 | 0.029 |

| 0.065 | 0.114 | 0.116 | 0.058 | 0.036 | 0.093 |

| 0.056 | 0.000 | 0.160 | 0.090 | 0.017 | 0.000 |

| 0.119 | 0.124 | 0.134 | 0.131 | 0.133 | 0.173 |

| 0.042 | 0.142 | 0.117 | 0.150 | 0.135 | 0.000 |

| 0.044 | 0.124 | 0.073 | 0.121 | 0.087 | 0.134 |

| 0.163 | 0.114 | 0.066 | 0.088 | 0.115 | 0.163 |

| 0.126 | 0.000 | 0.090 | 0.010 | 0.024 | 0.000 |

| 0.000 | 0.124 | 0.000 | 0.155 | 0.146 | 0.000 |

| 0.172 | 0.119 | 0.147 | 0.120 | 0.109 | 0.127 |

| 0.000 | 0.114 | 0.096 | 0.154 | 0.146 | 0.156 |

| 0.052 | 0.132 | 0.119 | 0.089 | 0.051 | 0.000 |

| 0.089 | 0.000 | 0.103 | 0.128 | 0.119 | 0.154 |

| 0.051 | 0.122 | 0.127 | 0.019 | 0.129 | 0.112 |

| 0.050 | 0.175 | 0.126 | 0.077 | 0.124 | 0.000 |

| 0.165 | 0.124 | 0.015 | 0.021 | 0.023 | 0.069 |

| 0.000 | 0.124 | 0.014 | 0.155 | 0.146 | 0.169 |

| 0.156 | 0.158 | 0.049 | 0.077 | 0.035 | 0.000 |

| 0.031 | 0.000 | 0.192 | 0.038 | 0.074 | 0.000 |

| 0.179 | 0.103 | 0.132 | 0.154 | 0.132 | 0.173 |

| 0.134 | 0.124 | 0.109 | 0.155 | 0.146 | 0.175 |

| 0.121 | 0.155 | 0.104 | 0.106 | 0.095 | 0.000 |

| 0.173 | 0.114 | 0.024 | 0.088 | 0.115 | 0.000 |

| 0.133 | 0.114 | 0.088 | 0.088 | 0.115 | 0.163 |

| 0.056 | 0.168 | 0.065 | 0.112 | 0.029 | 0.034 |

| 0.000 | 0.124 | 0.062 | 0.155 | 0.146 | 0.181 |

| 0.039 | 0.111 | 0.141 | 0.063 | 0.139 | 0.000 |

| 0.019 | 0.152 | 0.043 | 0.157 | 0.142 | 0.132 |

| 0.137 | 0.122 | 0.104 | 0.121 | 0.139 | 0.151 |

| 0.090 | 0.147 | 0.133 | 0.012 | 0.076 | 0.040 |

| 0.055 | 0.162 | 0.049 | 0.078 | 0.131 | 0.102 |

| 0.120 | 0.122 | 0.176 | 0.136 | 0.147 | 0.156 |

| 0.169 | 0.000 | 0.180 | 0.128 | 0.006 | 0.000 |

| 0.117 | 0.124 | 0.148 | 0.134 | 0.069 | 0.131 |

| 0.061 | 0.114 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.107 | 0.118 |

| 0.161 | 0.132 | 0.099 | 0.089 | 0.125 | 0.000 |

| 0.158 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.124 | 0.136 | 0.181 |

| 0.134 | 0.124 | 0.034 | 0.079 | 0.080 | 0.137 |

| 0.152 | 0.114 | 0.008 | 0.076 | 0.079 | 0.109 |

| 0.175 | 0.142 | 0.032 | 0.150 | 0.152 | 0.000 |

| 0.000 | 0.114 | 0.176 | 0.154 | 0.146 | 0.173 |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.063 | 0.112 | 0.119 | 0.181 |

| 0.106 | 0.124 | 0.056 | 0.030 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| 0.158 | 0.114 | 0.128 | 0.137 | 0.126 | 0.160 |

| 0.133 | 0.114 | 0.096 | 0.135 | 0.135 | 0.175 |

| 0.052 | 0.132 | 0.022 | 0.089 | 0.141 | 0.000 |

| 0.165 | 0.000 | 0.023 | 0.072 | 0.137 | 0.178 |

| 0.125 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.040 | 0.076 | 0.118 |

| 0.030 | 0.114 | 0.159 | 0.056 | 0.067 | 0.107 |

| 0.092 | 0.000 | 0.047 | 0.075 | 0.104 | 0.000 |

| 0.175 | 0.000 | 0.127 | 0.091 | 0.089 | 0.000 |

| 0.173 | 0.114 | 0.175 | 0.115 | 0.036 | 0.059 |

| Si+ | Si− | Si+ Si− | Si−/(Si+ Si−) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0747 | 0.0283 | 0.1031 | 0.2749 |

| 0.0196 | 0.0336 | 0.0531 | 0.6321 |

| 0.0433 | 0.0306 | 0.0739 | 0.4142 |

| 0.0395 | 0.0339 | 0.0734 | 0.4621 |

| 0.0675 | 0.0637 | 0.1312 | 0.4852 |

| 0.0187 | 0.0278 | 0.0465 | 0.5972 |

| 0.0128 | 0.0299 | 0.0428 | 0.6996 |

| 0.0355 | 0.0419 | 0.0774 | 0.5410 |

| 0.0703 | 0.0732 | 0.1436 | 0.5101 |

| 0.0758 | 0.0676 | 0.1434 | 0.4712 |

| 0.0368 | 0.0403 | 0.0771 | 0.5232 |

| 0.0283 | 0.0165 | 0.0448 | 0.3691 |

| 0.0132 | 0.0325 | 0.0458 | 0.7106 |

| 0.0323 | 0.0202 | 0.0525 | 0.3845 |

| 0.0475 | 0.0528 | 0.1003 | 0.5265 |

| 0.0713 | 0.0703 | 0.1416 | 0.4963 |

| 0.0662 | 0.0562 | 0.1224 | 0.4588 |

| 0.0571 | 0.0514 | 0.1085 | 0.4738 |

| 0.0283 | 0.0461 | 0.0744 | 0.6198 |

| 0.0479 | 0.0556 | 0.1035 | 0.5376 |

| 0.0671 | 0.0674 | 0.1344 | 0.5011 |

| 0.0325 | 0.0367 | 0.0693 | 0.5302 |

| 0.0713 | 0.0686 | 0.1399 | 0.4907 |

| 0.0295 | 0.0150 | 0.0445 | 0.3369 |

| 0.0633 | 0.0561 | 0.1194 | 0.4700 |

| 0.0138 | 0.0310 | 0.0447 | 0.6925 |

| 0.0450 | 0.0289 | 0.0739 | 0.3910 |

| 0.0460 | 0.0396 | 0.0856 | 0.4626 |

| 0.0760 | 0.0716 | 0.1476 | 0.4850 |

| 0.0672 | 0.0705 | 0.1377 | 0.5121 |

| 0.0423 | 0.0386 | 0.0809 | 0.4770 |

| 0.0300 | 0.0418 | 0.0718 | 0.5819 |

| 0.0344 | 0.0229 | 0.0574 | 0.3995 |

| 0.0464 | 0.0438 | 0.0902 | 0.4854 |

| 0.0232 | 0.0229 | 0.0461 | 0.4962 |

| 0.0656 | 0.0705 | 0.1361 | 0.5181 |

| 0.0407 | 0.0375 | 0.0782 | 0.4792 |

| 0.0596 | 0.0549 | 0.1145 | 0.4795 |

| 0.0624 | 0.0678 | 0.1302 | 0.5209 |

| 0.0206 | 0.0249 | 0.0455 | 0.5476 |

| 0.0480 | 0.0310 | 0.0791 | 0.3925 |

| 0.0504 | 0.0622 | 0.1126 | 0.5523 |

| 0.0676 | 0.0612 | 0.1288 | 0.4749 |

| 0.0377 | 0.0337 | 0.0715 | 0.4720 |

| 0.0559 | 0.0572 | 0.1131 | 0.5061 |

| 0.0539 | 0.0497 | 0.1036 | 0.4797 |

| 0.0455 | 0.0421 | 0.0876 | 0.4806 |

| 0.0427 | 0.0458 | 0.0885 | 0.5178 |

| 0.0740 | 0.0649 | 0.1389 | 0.4671 |

| 0.0384 | 0.0445 | 0.0829 | 0.5368 |

| 0.0291 | 0.0239 | 0.0530 | 0.4518 |

| 0.0631 | 0.0735 | 0.1366 | 0.5380 |

| 0.0662 | 0.0719 | 0.1381 | 0.5204 |

| 0.0367 | 0.0426 | 0.0793 | 0.5370 |

| 0.0327 | 0.0408 | 0.0734 | 0.5553 |

| 0.0623 | 0.0660 | 0.1283 | 0.5143 |

| 0.0461 | 0.0407 | 0.0868 | 0.4692 |

| 0.0757 | 0.0687 | 0.1443 | 0.4757 |

| 0.0370 | 0.0313 | 0.0683 | 0.4584 |

| 0.0649 | 0.0576 | 0.1225 | 0.4703 |

| 0.0592 | 0.0648 | 0.1240 | 0.5224 |

| 0.0408 | 0.0410 | 0.0818 | 0.5015 |

| 0.0570 | 0.0510 | 0.1080 | 0.4722 |

| 0.0602 | 0.0674 | 0.1276 | 0.5283 |

| 0.0036 | 0.0387 | 0.0423 | 0.9159 |

| 0.0530 | 0.0595 | 0.1125 | 0.5288 |

| 0.0577 | 0.0481 | 0.1058 | 0.4548 |

| 0.0318 | 0.0432 | 0.0751 | 0.5762 |

| 0.0652 | 0.0685 | 0.1337 | 0.5124 |

| 0.0575 | 0.0590 | 0.1165 | 0.5066 |

| 0.0500 | 0.0523 | 0.1023 | 0.5111 |

| 0.0368 | 0.0466 | 0.0834 | 0.5593 |

| 0.0713 | 0.0683 | 0.1396 | 0.4895 |

| 0.0709 | 0.0625 | 0.1333 | 0.4684 |

| 0.0354 | 0.0331 | 0.0685 | 0.4828 |

| 0.0600 | 0.0686 | 0.1287 | 0.5335 |

| 0.0657 | 0.0704 | 0.1361 | 0.5172 |

| 0.0426 | 0.0318 | 0.0744 | 0.4277 |

| 0.0642 | 0.0677 | 0.1319 | 0.5130 |

| 0.0455 | 0.0463 | 0.0918 | 0.5045 |

| 0.0520 | 0.0479 | 0.0998 | 0.4795 |

| 0.0252 | 0.0196 | 0.0448 | 0.4372 |

| 0.0113 | 0.0361 | 0.0473 | 0.7617 |

| 0.0317 | 0.0498 | 0.0814 | 0.6112 |

| Countries | Ranking ESG Score by Refinitiv Eikon | Ranking ESG Score by TOPSIS Method | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Czech Republic | 0.9432 | 0.2749 |

| 2 | Iceland | 0.9293 | 0.6321 |

| 3 | United Kingdom | 0.9195 | 0.4142 |

| 4 | Belgium | 0.9171 | 0.4621 |

| 5 | United Kingdom | 0.9163 | 0.4852 |

| 6 | Switzerland | 0.9117 | 0.5972 |

| 7 | Norway | 0.8968 | 0.6996 |

| 8 | Germany | 0.8960 | 0.5410 |

| 9 | Ireland | 0.8939 | 0.5101 |

| 10 | United Kingdom | 0.8925 | 0.4712 |

| 11 | Netherlands | 0.8787 | 0.5232 |

| 12 | Switzerland | 0.8782 | 0.3691 |

| 13 | Spain | 0.8713 | 0.7106 |

| 14 | France | 0.8563 | 0.3845 |

| 15 | United Kingdom | 0.8524 | 0.5265 |

| 16 | Italy | 0.8454 | 0.4963 |

| 17 | United Kingdom | 0.8451 | 0.4588 |

| 18 | United Kingdom | 0.8411 | 0.4738 |

| 19 | Italy | 0.8408 | 0.6198 |

| 20 | Switzerland | 0.8384 | 0.5376 |

| 21 | United Kingdom | 0.8335 | 0.5011 |

| 22 | Switzerland | 0.8274 | 0.5302 |

| 23 | United Kingdom | 0.8245 | 0.4907 |

| 24 | Germany | 0.8241 | 0.3369 |

| 25 | United Kingdom | 0.8226 | 0.4700 |

| 26 | France | 0.8180 | 0.6925 |

| 27 | United Kingdom | 0.8172 | 0.3910 |

| 28 | France | 0.8163 | 0.4626 |

| 29 | Switzerland | 0.8150 | 0.4850 |

| 30 | United Kingdom | 0.8126 | 0.5121 |

| 31 | Liechtenstein | 0.8095 | 0.4770 |

| 32 | United Kingdom | 0.7991 | 0.5819 |

| 33 | Sweden | 0.7979 | 0.3995 |

| 34 | United Kingdom | 0.7902 | 0.4854 |

| 35 | Germany | 0.7871 | 0.4962 |

| 36 | United Kingdom | 0.7852 | 0.5181 |

| 37 | Italy | 0.7848 | 0.4792 |

| 38 | Switzerland | 0.7820 | 0.4795 |

| 39 | United Kingdom | 0.7818 | 0.5209 |

| 40 | Norway | 0.7810 | 0.5476 |

| 41 | United Kingdom | 0.7800 | 0.3925 |

| 42 | Norway | 0.7758 | 0.5523 |

| 43 | United Kingdom | 0.7718 | 0.4749 |

| 44 | Germany | 0.7713 | 0.4720 |

| 45 | United Kingdom | 0.7670 | 0.5061 |

| 46 | Sweden | 0.7646 | 0.4797 |

| 47 | Switzerland | 0.7640 | 0.4806 |

| 48 | United Kingdom | 0.7633 | 0.5178 |

| 49 | United Kingdom | 0.7627 | 0.4671 |

| 50 | Ireland | 0.7604 | 0.5368 |

| 51 | United Kingdom | 0.7593 | 0.4518 |

| 52 | United Kingdom | 0.7589 | 0.5380 |

| 53 | United Kingdom | 0.7533 | 0.5204 |

| 54 | Italy | 0.7494 | 0.5370 |

| 55 | United Kingdom | 0.7489 | 0.5553 |

| 56 | United Kingdom | 0.7478 | 0.5143 |

| 57 | Romania | 0.7460 | 0.4692 |

| 58 | United Kingdom | 0.7436 | 0.4757 |

| 59 | Poland | 0.7430 | 0.4584 |

| 60 | Russia | 0.7384 | 0.4703 |

| 61 | Greece | 0.7369 | 0.5224 |

| 62 | Malta | 0.7356 | 0.5015 |

| 63 | France | 0.7326 | 0.4722 |

| 64 | Greece | 0.7324 | 0.5283 |

| 65 | Denmark | 0.7324 | 0.9159 |

| 66 | United Kingdom | 0.7320 | 0.5288 |

| 67 | France | 0.7316 | 0.4548 |

| 68 | Germany | 0.7260 | 0.5762 |

| 69 | Switzerland | 0.7254 | 0.5124 |

| 70 | United Kingdom | 0.7240 | 0.5066 |

| 71 | United Kingdom | 0.7233 | 0.5111 |

| 72 | Italy | 0.7214 | 0.5593 |

| 73 | United Kingdom | 0.7184 | 0.4895 |

| 74 | Guernsey | 0.7168 | 0.4684 |

| 75 | United Kingdom | 0.7148 | 0.4828 |

| 76 | United Kingdom | 0.7112 | 0.5335 |

| 77 | United Kingdom | 0.7112 | 0.5172 |

| 78 | Germany | 0.7094 | 0.4277 |

| 79 | Switzerland | 0.7092 | 0.5130 |

| 80 | Norway | 0.7075 | 0.5045 |

| 81 | United Kingdom | 0.7053 | 0.4795 |

| 82 | Sweden | 0.7048 | 0.4372 |

| 83 | Ireland | 0.7005 | 0.7617 |

| 84 | United Kingdom | 0.7004 | 0.6112 |

References

- Abdelkader, Mohamed G., Yongqiang Gao, and Ahmed A. Elamer. 2024. Board Gender Diversity and ESG Performance: The Mediating Role of Temporal Orientation in South Africa Context. Journal of Cleaner Production 440: 140728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnese, Paolo, Francesca Battaglia, Francesco Busato, and Simone Taddeo. 2023. ESG Controversies and Governance: Evidence from the Banking Industry. Finance Research Letters 53: 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnese, Paolo, Francesca Romana Arduino, Emma Bruno, and Gianfranco Antonio Vento. 2024. On the Road to Sustainability: The Role of Board Characteristics in Driving ESG Performance in Africa. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 95: 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alola, Andrew Adewale, Ali Celik, Hephzibah Onyeje Obekpa, Ojonugwa Usman, and Chukwuemeka Echebiri. 2023. The Making-or-Breaking of Material and Resource Efficiency in the Nordics. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption 11: 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, Guler, Nuray Tezcan, Ozlem Kutlu Furtuna, and Evrim Hacioglu Kazak. 2017. Corporate Sustainability Measurement Based on Entropy Weight and TOPSIS: A Turkish Banking Case Study. Meditari Accountancy Research 25: 391–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atenidegbe, Olanrewaju Fred, and Kehinde Anthony Mogaji. 2023. Modeling Assessment of Groundwater Vulnerability to Contamination Risk in a Typical Basement Terrain Using TOPSIS-Entropy Developed Vulnerability Data Mining Technique. Heliyon 9: e18371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, Jeongseok, Doojin Ryu, and Robert I. Webb. 2023. ESG Controversy as a Potential Asset-Pricing Factor. Finance Research Letters 58: 104315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennouri, Moez, Anastasia Cozarenco, and Samuel Anokye Nyarko. 2024. Women on Boards and Performance Trade-Offs in Social Enterprises: Insights from Microfinance. Journal of Business Ethics 190: 165–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benuzzi, Matteo, Klaudijo Klaser, and Karoline Bax. 2024. Which ESG+F Dimension Matters Most to Retail Investors? An Experimental Study on Financial Decisions and Future Generations. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 41: 100882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, Rahul, and Gerard Seijts. 2021. Leader Character in the Boardroom. Organizational Dynamics 50: 100751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruch, Nils, Michèle Knodt, and Marc Ringel. 2024. Advocating Harder Soft Governance for the European Green Deal. Stakeholder Perspectives on the Revision of the EU Governance Regulation. Energy Policy 192: 114255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira dos Santos, Murillo, and Fábio Henrique Pereira. 2022. ESG Performance Scoring Method to Support Responsible Investments in Port Operations. Case Studies on Transport Policy 10: 664–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Konan, Vincent Y. S. Chen, Yu Fang Huang, and Jia Wen Liang. 2023. Outside Directors’ Equity Incentives and Strategic Alliance Decisions. Journal of Corporate Finance 79: 102381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, Seungmin, Steve Matsunaga, and Shan Wang. 2022. Effective Board Monitoring over Earnings Reports and Forecasts: Evidence from CFO Outside Director Appointments. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 41: 106981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Fei, Yue-Hu Liu, and Xue-Zhao Chen. 2024. ESG Performance and Business Risk—Empirical Evidence from China’s Listed Companies. Innovation and Green Development 3: 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yashuo, Ranran Ning, Tong Yang, Shangjun Feng, and Chunjiang Yang. 2018. Is transformational leadership always good for employee task performance? Examining curvilinear and moderated relationships. Frontiers of Business Research in China 12: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Shaner. 2024. Are Women Greener? Board Gender Diversity and Corporate Green Technology Innovation in China. International Review of Economics and Finance 93: 1001–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, Dan S., Oliver Zhen Li, Albert Tsang, and Yong George Yang. 2012. Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Gourav, Rajiv K Srivastava, and Samir K Srivastava. 2018. A Generalised Fuzzy TOPSIS With Improved Closeness Coefficient. Expert Systems with Applications 96: 185–95. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3451799 (accessed on 5 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ferriani, Fabrizio. 2023. Issuing Bonds during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Was There an ESG Premium? International Review of Financial Analysis 88: 102653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Yuan, Jinyu Chen, and Ran Liu. 2024. ESG Rating Disagreement and Corporate Green Innovation Bubbles: Evidence from Chinese A-Share Listed Firms. International Review of Financial Analysis 95: 103495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoor, Abdul, and Ammar Ali Gull. 2024. Do Co-Opted Boards Protect CEOs from ESG Controversies? Finance Research Letters 63: 105263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, Srishti, and Maria Llop. 2024. The Shipping Industry under the EU Green Deal: An Input-Output Impact Analysis. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 182: 104035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, Paul, and Charles Fay. 1994. Outside Director Compensation and Firm Performance. Human Resource Management 33: 111–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Xu, Qinlei Jing, and Hao Chen. 2023. The Impact of Environmental Tax Laws on Heavy-Polluting Enterprise ESG Performance: A Stakeholder Behavior Perspective. Journal of Environmental Management 344: 118578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, Matthias. 2024. The European Green Deal, Retail Investors and Sustainable Investments: A Perspective Article Covering Economic, Behavioral, and Regulatory Insights. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 7: 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Qiongyu, Jiali Fang, Xiaolong Xue, and Hongming Gao. 2023. Does Digital Innovation Cause Better ESG Performance? An Empirical Test of a-Listed Firms in China. Research in International Business and Finance 66: 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Ying Sophie, and Mengyu Li. 2019. Are Overconfident Executives Alike? Overconfident Executives and Compensation Structure: Evidence from China. North American Journal of Economics and Finance 48: 434–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, Jeong Hoon, Natalie Kyung Won Kim, and Jae Yong Shin. 2024. Politically Connected Outside Directors and the Value of Cash Holdings. Finance Research Letters 62: 105124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Ga Young, Hyoung Goo Kang, and Woojin Kim. 2022. Corporate Executives’ Incentives and ESG Performance. Finance Research Letters 49: 103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Hongli, Wenjie Hu, and Pengcheng Jiang. 2024. Does ESG Performance Affect Corporate Tax Avoidance? Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters 61: 105056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Xinru, Xiaoxu Chen, and Zhiming Ao. 2024. ESG Rating, Board Faultlines, and Corporate Performance. Research in International Business and Finance 72: 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, Mustafa Tevfik, Dilvin Taşkın, Muhammad Shahbaz, Serpil Kılıç Depren, and Ugur Korkut Pata. 2024. Effects of Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG)Disclosures on ESGscores: Investigating Therole Ofcorporategovernance Forpubliclytraded Turkishcompanies. Journal of Environmental Management 368: 122205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, Harpreet, Surbhi Gupta, and Arvind Dhingra. 2023. Selection of solar panel using entropy TOPSIS technique. Materials Today: Proceedings. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneth David, Lemuel, Jianling Wang, Vanessa Angel, and Meiling Luo. 2024. Environmental Commitments and Innovation in China’s Corporate Landscape: An Analysis of ESG Governance Strategies. Journal of Environmental Management 349: 119529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, Ishwar, and Frode Kjærland. 2023. Sustainability Reporting Practices and Environmental Performance amongst Nordic Listed Firms. Journal of Cleaner Production 418: 138172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiohos, Apostolos, and Nikolaos Sariannidis. 2010. Determinants of the Asymmetric Gold Market. Investment Management and Financial Innovations 7: 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kostyuchenko, Nadiya, Katharina Reidl, and Rolf Wüstenhagen. 2024. Does Citizen Participation Improve Acceptance of a Green Deal? Evidence from Choice Experiments in Ukraine and Switzerland. Energy Policy 189: 114106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Aifan, Junxue Li, Limin Wen, and Yi Zhang. 2023. When Trackers Are Aware of ESG: Do ESG Ratings Matter to Tracking Error Portfolio Performance? Economic Modelling 125: 106346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xiaoqian, Javier Cifuentes-Faura, Shikuan Zhao, and Long Wang. 2024. The Impact of Government Environmental Attention on Firms’ ESG Performance: Evidence from China. Research in International Business and Finance 67: 102124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallidis, Ioannis, Grigoris Giannarakis, and Nikolaos Sariannidis. 2024. Impact of Board Gender Diversity on Environmental, Social, and ESG Controversies Performance: The Moderating Role of United Nations Global Compact and ISO. Journal of Cleaner Production 444: 141047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Geeti, Archana Patro, and Aviral Kumar Tiwari. 2024. Does Climate Governance Moderate the Relationship between ESG Reporting and Firm Value? Empirical Evidence from India. International Review of Economics and Finance 91: 920–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Jordan, Throstur Olaf Sigurjonsson, Nikolaos Kavadis, and Stefan Wendt. 2024. Green Bonds and Sustainable Business Models in Nordic Energy Companies. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 7: 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, Niels Oliver, Christoph Böhringer, Knut Einar Rosendahl, and Torjus Folsland Bolkesjø. 2023. Impacts of Green Deal Policies on the Nordic Power Market. Utilities Policy 80: 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, Cláudia Rafaela Saraiva de Melo Simões, Adiel Teixeira de Almeida-Filho, and Rachel Perez Palha. 2023. A TOPSIS-based framework for construction projects’ portfolio selection in the public sector. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noei, Shirin, Arman Sargolzaei, Kang Yen, Saman Sargolzaei, and Nansong Wu. 2017. Ecopreneur Selection Using Fuzzy Similarity TOPSIS Variants. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management 7: 864–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Oh, Hyun Jung, Byoungkwan Lee, Hye Hyun Ma, Dayeoun Jang, and Sejin Park. 2024. A Preliminary Study for Developing Perceived ESG Scale to Measure Public Perception toward Organizations’ ESG Performance. Public Relations Review 50: 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omo-Okoro, Patricia N., Christopher J. Curtis, and Kriveshini Pillay. 2023. Importance of Phosphorus Raw Materials in Green Deal Strategies. In Sustainable and Circular Management of Resources and Waste towards a Green Deal. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 213–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Jian-Yang. 2017. The SME Board Stock Price Trend Analysis and Investment Strategy Under the Fractal Market Hypothesis. DEStech Transactions on Social Science, Education and Human Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazou, Konstantina, Christos Lemonakis, Ioannis Passas, Constantin Zopounidis, and Alexandros Garefalakis. 2024. ESG-Driven Ecopreneur Selection in European Financial Institutions: Entropy and TOPSIS Analysis. Management Decision, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Suárez, Javier, and Ana B. Alonso-Conde. 2024. Have Shifts in Investor Tastes Led the Market Portfolio to Capture ESG Preferences? International Review of Financial Analysis 91: 103019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Lei, Jianing Li, and Siqi Huang. 2024. News or Noise? ESG Disclosure and Stock Price Synchronicity. International Review of Financial Analysis 95: 103483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryou, Ji Woo, Albert Tsang, and Kun Tracy Wang. 2022. Product Market Competition and Voluntary Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures†. Contemporary Accounting Research 39: 1215–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, Marcel, Florian Spitzer, Simone Haeckl, Alexia Gaudeul, Erich Kirchler, Stefan Palan, and Katharina Gangl. 2024. Can Information Provision and Preference Elicitation Promote ESG Investments? Evidence from a Large, Incentivized Online Experiment. Journal of Banking and Finance 161: 107114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklavos, George, George Theodossiou, Zacharias Papanikolaou, Christos Karelakis, and Konstantina Ragazou. 2024. Environmental, Social, and Governance-Based Artificial Intelligence Governance: Digitalizing Firms’ Leadership and Human Resources Management. Sustainability 16: 7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Yanqi, Dan Zhao, and Yuanyuan Cao. 2024. The Impact of ESG Performance, Reporting Framework, and Reporting Assurance on the Tone of ESG Disclosures: Evidence from Chinese Listed Firms. Journal of Cleaner Production 466: 142698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan, Enyang Besong, Agbortarh Besong Matilda, and Manases Mbengwor Natu. 2024. Examining the Nexus between Governance and Financial Inclusion in the Nordic-Baltic Region: Bank Stability as a Moderator. Heliyon 10: e34227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Bowen, Jiayi Yu, and Zhilong Tian. 2024. The Impact of Market-Based Environmental Regulation on Corporate ESG Performance: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on China’s Carbon Emission Trading Scheme. Heliyon 10: e26687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzitiridou-Chatzopoulou, Maria, Georgia Zournatzidou, Eirini Orovou, Maria Lithoxopoulou, Eftychia Drogouti, George Sklavos, Evangelia Antoniou, and Christos Tsakalidis. 2024. Evaluating Malnutrition Practices and Mother’s Education on Children Failure to Thrive Symptoms Using Entropy-Weight and TOPSIS Method. Children 11: 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Geer, Sara A., and Peter Bühlmann. 2009. On the Conditions Used to Prove Oracle Results for the Lasso. Electronic Journal of Statistics 3: 1360–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vara Prasad, Majeti Narasimha, Marzena Smol, and Helena Freitas. 2023. Achieving Sustainable Development Goals via Green Deal Strategies. In Sustainable and Circular Management of Resources and Waste towards a Green Deal. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Miao, Yiduo Wang, and Shouxun Wen. 2024. ESG Performance and Green Innovation in New Energy Enterprises: Does Institutional Environment Matter? Research in International Business and Finance 71: 102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Qiong, Huajie Wang, and Kemin Wang. 2024. Making Outside Directors inside: Independent Directors’ Corporate Site Visits and Real Earnings Management. British Accounting Review 56: 101429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Ruirui, and Zhongfeng Qin. 2024. Asymmetric Volatility Spillovers among New Energy, ESG, Green Bond and Carbon Markets. Energy 292: 130504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Zihao, Jun Gao, Chengdi Luo, Hui Xu, and Guanqun Shi. 2024. How Does Boardroom Diversity Influence the Relationship between ESG and Firm Financial Performance? International Review of Economics and Finance 89: 713–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Jialin, Yulong Huang, and Xiaowei Liao. 2024. Help or Hindrance? The Impact of Female Executives on Corporate ESG Performance in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 437: 140614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Lei, and Yuanyuan Yang. 2024. How Does Digital Finance Influence Corporate Greenwashing Behavior? International Review of Economics and Finance 93: 359–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Mengtao, Wenwen Li, Yalin Luo, and Wenchuan Chen. 2023. Government Audit Supervision, Financialization, and Executives’ Excess Perks: Evidence from Chinese State-Owned Enterprises. International Review of Financial Analysis 89: 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zournatzidou, Georgia, and Christos Floros. 2023. Hurst Exponent Analysis: Evidence from Volatility Indices and the Volatility of Volatility Indices. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16: 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zournatzidou, Georgia, Ioannis Mallidis, Dimitrios Farazakis, and Christos Floros. 2024. Enhancing Bitcoin Price Volatility Estimator Predictions: A Four-Step Methodological Approach Utilizing Elastic Net Regression. Mathematics 12: 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Description | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| C1. Executive Members Gender Diversity, Percent Score | Represents the proportion of women in leadership positions (Zhang et al. 2023; Yan et al. 2024). | Percent |

| C2. Board Attendance Score | Specifies whether the financial institution discloses information on the presence of individual board members at board meetings (Ghafoor and Gull 2024). | Percent |

| C3. Board Tenure Score | Displays the mean duration of tenure for each member of the board (Bennouri et al. 2024; Wu et al. 2024). | Percent |

| C4. Non-Executive Board Members Score | Provides the proportion of non-executive board members. | Percent |

| C5. Independent Board Members Score | Displays the proportion of board members who are independent, as indicated by each of the chosen financial institutions (Wu et al. 2024; Ji et al. 2024). | Percent |

| C6. Strictly Independent Board Members Score | The percentage of board members who meet specific independence criteria, including not being employed by the company, not having served on the board for more than ten years, not being a major shareholder with more than 5% of holdings, not having membership on multiple boards, not having immediate family ties to the corporation, and not receiving any compensation other than board service remuneration, is indicated (Bhardwaj and Seijts 2021). | Percent |

| Criterion | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.93089 | 0.918287 | 0.954517 | 0.963958 | 0.976212 | 0.870133 | |

| D = 1 − | 0.06911 | 0.081713 | 0.045483 | 0.036042 | 0.023788 | 0.129867 |

| 0.17904 | 0.211691 | 0.117829 | 0.093372 | 0.061628 | 0.33644 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zournatzidou, G. Evaluating Executives and Non-Executives’ Impact toward ESG Performance in Banking Sector: An Entropy Weight and TOPSIS Method. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100255

Zournatzidou G. Evaluating Executives and Non-Executives’ Impact toward ESG Performance in Banking Sector: An Entropy Weight and TOPSIS Method. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(10):255. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100255

Chicago/Turabian StyleZournatzidou, Georgia. 2024. "Evaluating Executives and Non-Executives’ Impact toward ESG Performance in Banking Sector: An Entropy Weight and TOPSIS Method" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 10: 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100255

APA StyleZournatzidou, G. (2024). Evaluating Executives and Non-Executives’ Impact toward ESG Performance in Banking Sector: An Entropy Weight and TOPSIS Method. Administrative Sciences, 14(10), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100255