From Gendered Entrepreneurial Cognition to Sustainable Performance: The Power of Women’s Entrepreneurial Capital in Emerging Economies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Conceptual Foundations: From Gendered Entrepreneurial Cognition to Sustainable Performance

2.2. Advancing the Theorization of Gendered Entrepreneurial Cognition

2.2.1. Conceptual Foundations and Propositions

- Proposition 1: GEC functions as a gendered cognitive filter that transforms lived experiences and socio-cultural roles into pathways for the development of WIC and WSC.

- Proposition 2: GEC generates mechanism-level processes—such as experiential learning, negotiation of social roles, and collective sensemaking—that enable women entrepreneurs to convert cognitive orientations into tangible intellectual and relational resources.

- Proposition 3: Compared with general entrepreneurial cognition models, GEC provides a context-specific explanatory framework that captures how gendered constraints and opportunities are cognitively processed, thereby fostering distinctive forms of entrepreneurial capital and sustainable performance.

2.2.2. Mechanism-Level Logic of GEC

2.3. Hypotheses Development

2.3.1. The Relationship Between GEC and WIC

2.3.2. The Relationship Between GEC and SP

2.3.3. The Relationship Between GEC and WSC

2.3.4. The Relationship Between WIC and SP

2.3.5. The Relationship Between WSC and SP

2.3.6. The Mediating Role of WIC and WSC

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Quantitative Phase

3.2.1. Population and Sample

3.2.2. Data Collection Procedure

3.2.3. Measurement of Constructs

3.2.4. Data Analysis

3.3. Qualitative Phase

3.3.1. Selection of Informants

3.3.2. Data Collection Techniques

- The role of GEC in strategic decision-making—examining how gender-based perceptions influence women entrepreneurs’ evaluation of opportunities and risks, and linking these insights with quantitative findings that GEC significantly affects SP.

- The development of WIC and WSC under resource constraints—investigating how women entrepreneurs build knowledge, skills, systems, and networks when formal resources are limited, thereby deepening the mediation pathway GEC → WIC/WSC → SP tested in the quantitative phase.

- Challenges and strategies in achieving SP—exploring adaptive strategies to balance economic, social, and environmental dimensions within the TBL framework, complementing quantitative evidence on the role of WIC and WSC in shaping SP.

3.3.3. Qualitative Data Analysis

- Confirm quantitative results, for example, by reinforcing evidence that GEC shapes SP both directly and through WIC and WSC.

- Explain hidden mechanisms, such as cultural factors, social norms, or family support that were not captured in the survey but influenced the development of WIC and WSC.

- Provide practical insights, including strategies of informal networking, community-based management practices, or local innovations that not only explain the relationships among variables but also offer concrete recommendations for empowerment policies targeting women entrepreneurs in emerging economies.

3.4. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Phases

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Phase

4.1.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

4.1.2. Structural Model Evaluation

4.1.3. Mediation Test

4.1.4. Common Method Bias (CMB) Test

4.1.5. Predictive Validity (PLSpredict)

4.2. Qualitative Phase

4.2.1. The Role of GEC in Strategic Decision-Making

4.2.2. Development of WIC Under Resource Constraints

4.2.3. The Role of WSC as Social Capital

4.2.4. Challenges and Strategies for Achieving SP

4.3. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement Items and Sources

| Variable | Dimension | Likert Statements | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEC (Gendered Entrepreneurial Cognition) | Cognitive lens based on gendered experience |

| Henry et al. (2021); Ahl and Marlow (2021) |

| WIC (Women’s Intellectual Capital) | Human and structural capital |

| Paoloni et al. (2023); Yang et al. (2024) |

| WSC (Women’s Social Capital) | Networks and trust |

| Sakamoto (2024); Chowdhury et al. (2024) |

| SP (Sustainable Performance) | Triple bottom line (economic, social, environmental) |

| Gu et al. (2022); Hasan et al. (2025) |

References

- Abane, J. A., Adamtey, R., & Kpeglo, R. (2024). The impact of social capital on business development in Ghana: Experiences of local-level businesses in the Kumasi metropolitan area. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 9, 100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A. S., Amin, H. M., Abdelghany, M., & Elamer, A. A. (2025). Assessing competitiveness through intellectual capital research: A systematic literature review and agenda for future research. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 35(1), 190–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R., Samadhiya, A., Banaitis, A., & Kumar, A. (2025). Entrepreneurial barriers in achieving sustainable business and cultivation of innovation: A resource-based view theory perspective. Management Decision, 63(4), 1207–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, A., Akanpaaba, P. A., Tukue, T., & Sarpong, A. (2025). Amplifying success in SMEs: Harnessing the joint power of social capital and new product development capability in developing economies. Africa Journal of Management, 11(1), 60–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahl, H., & Marlow, S. (2021). Exploring the false promise of entrepreneurship through a postfeminist critique of the enterprise policy discourse in Sweden and the UK. Human Relations, 74(1), 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M., Wu, Q., & Khattak, M. S. (2023). Intellectual capital, corporate social responsibility and sustainable competitive performance of small and medium-sized enterprises: Mediating effects of organizational innovation. Kybernetes, 52(10), 4014–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalde-Calonge, A., Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Sáez-Martínez, F. J. (2024). Fostering circular economy in small and medium-sized enterprises: The role of social capital, adaptive capacity, entrepreneurial orientation and a pro-sustainable environment. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(8), 8882–8899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A. D. A. S. M., & Carvalho, F. M. P. D. O. (2022). How dynamic managerial capabilities, entrepreneurial orientation, and operational capabilities impact microenterprises’ global performance. Sustainability, 15(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anser, M. K., Naeem, M., Ali, S., Huizhen, W., & Farooq, S. (2024). From knowledge to profit: Business reputation as a mediator in the impact of green intellectual capital on business performance. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 25(5/6), 1133–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Boateng, C., Mensah, H. K., & Asumah, S. (2023). Eco-intellectual capital and sustainability performance of SMEs: The moderating effect of eco-dynamic capability. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 2258614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atienza-Barba, M., del Brío-González, J., Mitre-Aranda, M., & Barba-Sánchez, V. (2025). Gender differences in the impact of ecological awareness on entrepreneurial intent. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 21(1), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babajide, A. A., Obembe, D., Solomon, H., & Woldesenbet, K. (2022). Microfinance and entrepreneurship: The enabling role of social capital amongst female entrepreneurs. International Journal of Social Economics, 49(8), 1152–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S., Garg, I., Jain, M., & Yadav, A. (2023). Improving the performance/competency of small and medium enterprises through intellectual capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 24(3), 830–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Nashwan, S. A., & Li, J. Z. (2025). AI-infused knowledge and green intellectual capital: Pathways to spur accounting performance drawn from RBV-KBV model and sustainability culture. Technology in Society, 82, 102913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calás, M. B., Smircich, L., & Bourne, K. A. (2009). Extending the boundaries: Reframing “entrepreneurship as social change” through feminist perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, L. (2023). Gender equality and development: Indonesia in a global context. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 59(2), 179–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. J., Michel, J. G., & Lin, W. (2021). Worlds apart? Connecting competitive dynamics and the resource-based view of the firm. Journal of Management, 47(7), 1820–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M. M. H., Islam, M. T., Ali, I., & Quaddus, M. (2024). The role of social capital, resilience, and network complexity in attaining supply chain sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(3), 2621–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2024). My 35 years in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 18(3), 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, E., Vătămănescu, E. M., Stăneiu, R. M., & Rusu, M. (2023). An exploratory study linking intellectual capital and technology management towards innovative performance in kibs. Sustainability, 15(2), 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwumah, P., Amaniampong, E. M., Animwah Kissiedu, J., & Adu Boahen, E. (2024). Association between entrepreneurial orientation and the performance of small and medium enterprises in Ghana: The role of network ties. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2302192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrehail, H., Aljahmani, R., Taamneh, A. M., Alsaad, A. K., Al-Okaily, M., & Emeagwali, O. L. (2024). The role of employees’ cognitive capabilities, knowledge creation and decision-making style in predicting the firm’s performance. EuroMed Journal of Business, 19(4), 943–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, M., Lukes, M., & Uhlaner, L. (2022). Disentangling succession and entrepreneurship gender gaps: Gender norms, culture, and family. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 997–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felin, T., Foss, N. J., Heimeriks, K. H., & Madsen, T. L. (2012). Microfoundations of routines and capabilities: Individuals, processes, and structure. Journal of Management Studies, 49(8), 1351–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felin, T., Foss, N. J., & Ployhart, R. E. (2015). The microfoundations movement in strategy and organization theory. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 575–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C. I., Ferreira, J. J., Veiga, P. M., Hu, Q., & Hughes, M. (2025). Dynamic capabilities as a moderator: Enhancing the international performance of SMEs with international entrepreneurial orientation. Review of Managerial Science, 19(4), 1073–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N. J., & Klein, P. G. (2020). Entrepreneurial opportunities: Who needs them? Academy of Management Perspectives, 34(3), 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N. J., Klein, P. G., Lien, L. B., Zellweger, T., & Zenger, T. (2021). Ownership competence. Strategic Management Journal, 42(2), 302–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.-C. D., & Welter, F. (2013). Gender identities and practices: Interpreting women entrepreneurs’ narratives. International Small Business Journal, 31(4), 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidage, M., & Bhide, S. (2025). Exploring the nexus between intellectual capital, green innovation, sustainability and financial performance in creative industry MSMEs. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 19(3), 457–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, D. A., Corbett, A. C., & McMullen, J. S. (2011). The cognitive perspective in entrepreneurship: An agenda for future research. Journal of Management Studies, 48(6), 1443–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W., Pan, H., Hu, Z., & Liu, Z. (2022). The triple bottom line of sustainable entrepreneurship and economic policy uncertainty: An empirical evidence from 22 countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 7758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S., Wei, M., Tzempelikos, N., & Shin, M. M. (2024). Women empowerment: Challenges and opportunities for sustainable development goals. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 27(4), 608–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., & Alamer, A. (2022). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, 1(3), 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Astrachan, C. B., Moisescu, O. I., Radomir, L., Sarstedt, M., Vaithilingam, S., & Ringle, C. M. (2021). Executing and interpreting applications of PLS-SEM: Updates for family business researchers. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 12(3), 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariyono, A., & Narsa, I. M. (2024). The value of intellectual capital in improving MSMEs’ competitiveness, financial performance, and business sustainability. Cogent Economics & Finance, 12(1), 2325834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M., Jannah, M., Supatminingsih, T., Ahmad, M. I. S., Sangkala, M., Najib, M., & Elpisah. (2024). Understanding the role of financial literacy, entrepreneurial literacy, and digital economic literacy on entrepreneurial creativity and MSMEs success: A knowledge-based view perspective. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2433708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M., Supatminingsih, T., Tahir, T., Guampe, F. A., Huruta, A. D., & Lu, C. Y. (2025). Sustainable agricultural knowledge-based entrepreneurship literacy in agricultural SMEs: Triple bottom line investigation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 11(1), 100466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendratmi, A., Salleh, M. C. M., Sukmaningrum, P. S., & Ratnasari, R. T. (2024). Toward SDG’s 8: How sustainability livelihood affecting survival strategy of woman entrepreneurs in Indonesia. World Development Sustainability, 5, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C., Coleman, S., Foss, L., Orser, B. J., & Brush, C. G. (2021). Richness in diversity: Towards more contemporary research conceptualisations of women’s entrepreneurship. International Small Business Journal, 39(7), 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C., & Lewis, K. V. (2023). The art of dramatic construction: Enhancing the context dimension in women’s entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Research, 155, 113440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hj Talip, S. N. S., & Wasiuzzaman, S. (2024). Influence of human capital and social capital on MSME access to finance: Assessing the mediating role of financial literacy. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 42(3), 458–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock-Doepgen, M., Heaton, S., Clauss, T., & Block, J. (2025). Identifying microfoundations of dynamic managerial capabilities for business model innovation. Strategic Management Journal, 46(2), 470–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, J. E., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, R. V. D., & Novas, J. C. (2024). Information and knowledge management, intellectual capital, and sustainable growth in networked small and medium enterprises. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15(1), 563–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakeesh, D. F. (2024). Female entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 26(3), 485–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabbaz, L., & Kuran, O. (2024). Empowering rural Lebanese female entrepreneurs: A resource-based perspective. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 29(01), 2450002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. H., Majid, A., Yasir, M., & Javed, A. (2021). Social capital and business model innovation in SMEs: Do organizational learning capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation really matter? European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(1), 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. R., Lin, K. H., Chen, C. H., Otero-Neira, C., & Svensson, G. (2022). TBL dominant logic for sustainability in oriental businesses. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 40(7), 837–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Li, J., & Zhai, Y. (2024). Intellectual capital and sustainability performance: The mediating role of digitalization. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 25(5/6), 867–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Wu, J., Zhang, D., & Ling, L. (2021). Gendered institutions and female entrepreneurship: A fuzzy-set QCA approach. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 36(1), 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukopoulos, A., Papadimitriou, D., & Glaveli, N. (2024). Unleashing the power of organizational social capital: Exploring the mediating role of social entrepreneurship orientation in social enterprises’ performances. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 30(5), 1290–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, J., & Kumar Jha, M. (2025). Do self-help groups possess the dimensions of social capital? Empirical evidence from India. International Journal of Social Economics, 52(4), 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, G., Vu, O. T. K., & Thanh, H. P. (2025). Understanding women entrepreneurship in Vietnam: Motivators and barriers through integration of two theoretical frameworks. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 32(2), 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R. K., Busenitz, L., Lant, T., McDougall, P. P., Morse, E. A., & Smith, J. B. (2002). Toward a theory of entrepreneurial cognition: Rethinking the people side of entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(2), 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral, I. H., Rahman, M. M., Rahman, M. S., Chowdhury, M. S., & Rahaman, M. S. (2024). Breaking barriers and empowering marginal women entrepreneurs in Bangladesh for sustainable economic growth: A narrative inquiry. Social Enterprise Journal, 20(4), 585–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, E., Gomes, S., & Lopes, J. M. (2025). Unveiling triple bottom line’s influence on business performance. Discover Sustainability, 6(1), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, N. H. M., Al Koliby, I. S., Al-Swidi, A. K., & Al-Hakimi, M. A. (2025). Women entrepreneurs and sustainable development: Promoting business performance from the low-income groups. Sustainable Futures, 9, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, S. K., Lee, C. H., & Amran, A. (2023). Assessing the influence of social capital and innovations on environmental performance of manufacturing SMEs. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(6), 3242–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmié, M., Rüegger, S., & Parida, V. (2023). Microfoundations in the strategic management of technology and innovation: Definitions, systematic literature review, integrative framework, and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 154, 113351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoloni, P., Modaffari, G., Ricci, F., & Della Corte, G. (2023). Intellectual capital between measurement and reporting: A structured literature review. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 24(1), 115–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Fernández, H., Rodríguez Escudero, A. I., Martín Cruz, N., & Delgado García, J. B. (2024). The impact of social capital on entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents: Differences between social capital online and offline. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 27(4), 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phonthanukitithaworn, C., Srisathan, W. A., Ketkaew, C., & Naruetharadhol, P. (2023). Sustainable development towards openness SME innovation: Taking advantage of intellectual capital, sustainable initiatives, and open innovation. Sustainability, 15(3), 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylypenko, H. M., Pylypenko, Y. I., Dubiei, Y. V., Solianyk, L. G., Pazynich, Y. M., Buketov, V., Smoliński, A., & Magdziarczyk, M. (2023). Social capital as a factor of innovative development. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(3), 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R., Subramaniam, N., Nair, V. K., Shivdas, A., Achuthan, K., & Nedungadi, P. (2022). Women entrepreneurship and sustainable development: Bibliometric analysis and emerging research trends. Sustainability, 14(15), 9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Solís, E. R., Mojarro-Durán, B. I., & Baños-Monroy, V. I. (2024). Family social capital as a mediator between socioemotional wealth and entrepreneurial orientation: Evidence from Mexican SMEs. Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 22(2), 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Farroñán, E. V., Arbulú Ballesteros, M. A., Mogollón García, F. S., Heredia Llatas, F. D., Farfán Chilicaus, G. C., Guzmán Valle, M. d. l. Á., García Juárez, H. D., Silva León, P. M., & Arbulú Castillo, J. C. (2024). Sustainability and rural empowerment: Developing women’s entrepreneurial skills through innovation. Sustainability, 16(23), 10226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A., Yousafzai, S., & Saeed, S. (2024). Breaking barriers and bridging gaps: The influence of entrepreneurship policies on women’s entry into entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 30(7), 1779–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhaiem, K., & Doloreux, D. (2024). Inbound open innovation in SMEs: A microfoundations perspective of dynamic capabilities. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 199, 123048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritala, P., Kianto, A., Vanhala, M., & Hussinki, H. (2023). To protect or not to protect? Renewal capital, knowledge protection and innovation performance. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(11), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, M. (2024). The role of social capital in community development: Insights from behavioral game theory and social network analysis. Sustainable Development, 32(5), 5240–5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, Z., Khan, M. A., Yang, Z., Khan, A., Haseeb, M., & Sarwar, A. (2021). An investigation of entrepreneurial SMEs’ network capability and social capital to accomplish innovativeness: A dynamic capability perspective. SAGE Open, 11(3), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M. H., & Malik, S. A. (2025). Driving firm performance with green intellectual capital: The key role of business sustainability in SMEs. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 26(3), 691–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D. A., Williams, T. A., & Patzelt, H. (2015). Thinking about entrepreneurial decision making: Review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 41(1), 11–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spender, J. C. (1996). Organizational knowledge, learning and memory: Three concepts in search of a theory. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 9(1), 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S., & Pandita, D. (2025). Unveiling the untapped potential: A comprehensive review of performance in women-owned firms. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 14(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, S., Rossano-Rivero, S., Davis, S., Wakkee, I., & Stroila, I. (2024). Pursuing entrepreneurial opportunities is not a choice: The interplay between gender norms, contextual embeddedness, and (in) equality mechanisms in entrepreneurial contexts. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 30(7), 1725–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swail, J., & Marlow, S. (2024). ‘Involuntary exit for personal reasons’—A gendered critique of the business exit decision. International Small Business Journal, 42(8), 966–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2014). The foundations of enterprise performance: Dynamic and ordinary capabilities in an (economic) theory of firms. Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(4), 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, B. T. T., & Nguyen, P. V. (2024). Driving business performance through intellectual capital, absorptive capacity, and innovation: The mediating influence of environmental compliance and innovation. Asia Pacific Management Review, 29(1), 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, J., Miranda, R., Azevedo, G., & Tavares, M. C. (2022). The impact of sustainable intellectual capital on sustainable performance: A case study. Sustainability, 14(8), 4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tran, D., Van Nguyen, P., Dinh, N. T. T., Huynh, T. N., & Van Ma, K. (2024). Exploring the impact of social capital on business performance: The role of dynamic capabilities, open innovation and government support. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 10(4), 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuciterna, R., Ruggeri, G., Mazzocchi, C., Manzella, S., & Corsi, S. (2024). Women’s entrepreneurial journey in developed and developing countries: A bibliometric review. Agricultural and Food Economics, 12(1), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y., & Wen, S. (2024). The relationship between dynamic capabilities and global value chain upgrading: The mediating role of innovation capability. Journal of Strategy and Management, 17(1), 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldesenbet Beta, K., Mwila, N. K., & Ogunmokun, O. (2024). A review of and future research agenda on women entrepreneurship in Africa. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 30(4), 1041–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuebker, R., Zenger, T., & Felin, T. (2023). The theory-based view: Entrepreneurial microfoundations, resources, and choices. Strategic Management Journal, 44(12), 2922–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., Luo, C., & Pan, L. (2024). Do digitalization and intellectual capital drive sustainable open innovation of natural resources sector? Evidence from China. Resources Policy, 88, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A. (2024). Relationship between human capital and entrepreneurship orientation from the intellectual capital perspective of innovative literacy. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 25(5/6), 1259–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C., Xia, W., & Feng, T. (2024). Adopting relationship trust and influence strategy to enhance green customer integration: A social exchange theory perspective. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 39(8), 1669–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Theory | Findings | Gap | Contribution to This Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barney (1991) | RBV | Competitive advantage derives from VRIN resources. | Limited focus on intangible and cognitive resources. | Extend RBV by highlighting intangible and gendered resources. |

| Felin et al. (2012); Foss and Klein (2020); Foss et al. (2021) | Microfoundations | Capabilities rooted in individual cognition, interactions, and practices. | Underexplored in women entrepreneurship research. | Position GEC as gendered microfoundation shaping resource mobilization. |

| Grant (1996); Spender (1996) | KBV | Knowledge and learning are core to sustainable advantage. | Gendered knowledge construction rarely examined. | Frame WIC as women-specific intellectual capital driving SP. |

| Coleman (1988); Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) | SCT | Social ties provide access to information, legitimacy, and resources. | Limited integration with GEC in emerging economies. | Frame WSC as external capital linking GEC and SP. |

| Calás et al. (2009); Jennings and Brush (2013) | Feminist Entrepreneurship | Gender norms shape entrepreneurial experiences and outcomes. | Few studies link cognition to sustainability outcomes. | Employ GEC to explain pathways to SP via WEC. |

| Ahl and Marlow (2021) | GEC | Women perceive and manage risks differently due to social norms. | Lack of mediation testing through intangible capital. | Highlight role of GEC in shaping WIC and WSC. |

| Shahbaz and Malik (2025); Gidage and Bhide (2025) | IC in SMEs | IC fosters innovation and business sustainability. | Rarely examined from a gendered perspective. | Conceptualize WIC as mediator between GEC and SP. |

| Ooi et al. (2023); Agyapong et al. (2025) | SC in SMEs | SC enhances innovation and collaboration for performance. | Limited research on women entrepreneurs in emerging economies. | Position WSC as mediator between GEC and SP. |

| Hasan et al. (2025); Gu et al. (2022); Nogueira et al. (2025) | TBL | SP must balance economic, social, and environmental goals. | Most studies assess only financial performance. | Employ TBL to capture holistic sustainability outcomes. |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Supporting Theory | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | GEC → WIC | RBV; microfoundations | Barney (1991); Teece (2014); Felin et al. (2015); Wuebker et al. (2023) |

| H2 | GEC → SP | RBV; cognitive perspective; gendered cognition | Henry and Lewis (2023); Srivastava and Pandita (2025) |

| H3 | GEC → WSC | Gendered cognition; SCT | Ahl and Marlow (2021); Babajide et al. (2022) |

| H4 | WIC → SP | RBV; KBV; TBL | Li et al. (2021); Hasan et al. (2025); Abdallah et al. (2025) |

| H5 | WSC → SP | SCT; RBV; TBL | Pylypenko et al. (2023); Zhou et al. (2024) |

| H6a | GEC → WIC → SP | RBV + microfoundations | Ritala et al. (2023); Bansal et al. (2023) |

| H6b | GEC → WSC → SP | RBV + microfoundations | Ramírez-Solís et al. (2024); Loukopoulos et al. (2024) |

| No. | District/City | Number of Samples | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Makassar City | 175 | 26.80 |

| 2 | Maros Regency | 110 | 16.85 |

| 3 | Pangkep Regency | 95 | 14.55 |

| 4 | Barru Regency | 90 | 13.78 |

| 5 | Gowa Regency | 100 | 15.31 |

| 6 | Bulukumba Regency | 83 | 12.71 |

| Total | 653 | 100.00 | |

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 21–30 years | 208 | 32.7 |

| 31–45 years | 296 | 46.5 | |

| >45 years | 133 | 20.8 | |

| Education | Secondary school | 182 | 28.6 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 346 | 54.3 | |

| Postgraduate | 109 | 17.1 | |

| Years of operation | ≤5 years | 232 | 35.5 |

| >5 years | 421 | 64.5 | |

| Total | - | 653 | 100.0 |

| Variable | Dimension | Indicators | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEC | Cognitive lens based on gendered experience |

| Henry et al. (2021); Ahl and Marlow (2021) |

| WIC | Human and structural capital |

| Paoloni et al. (2023); Yang et al. (2024) |

| WSC | Networks and trust |

| Sakamoto (2024); Chowdhury et al. (2024) |

| SP | Triple bottom line (economic, social, environmental) |

| Gu et al. (2022); Hasan et al. (2025) |

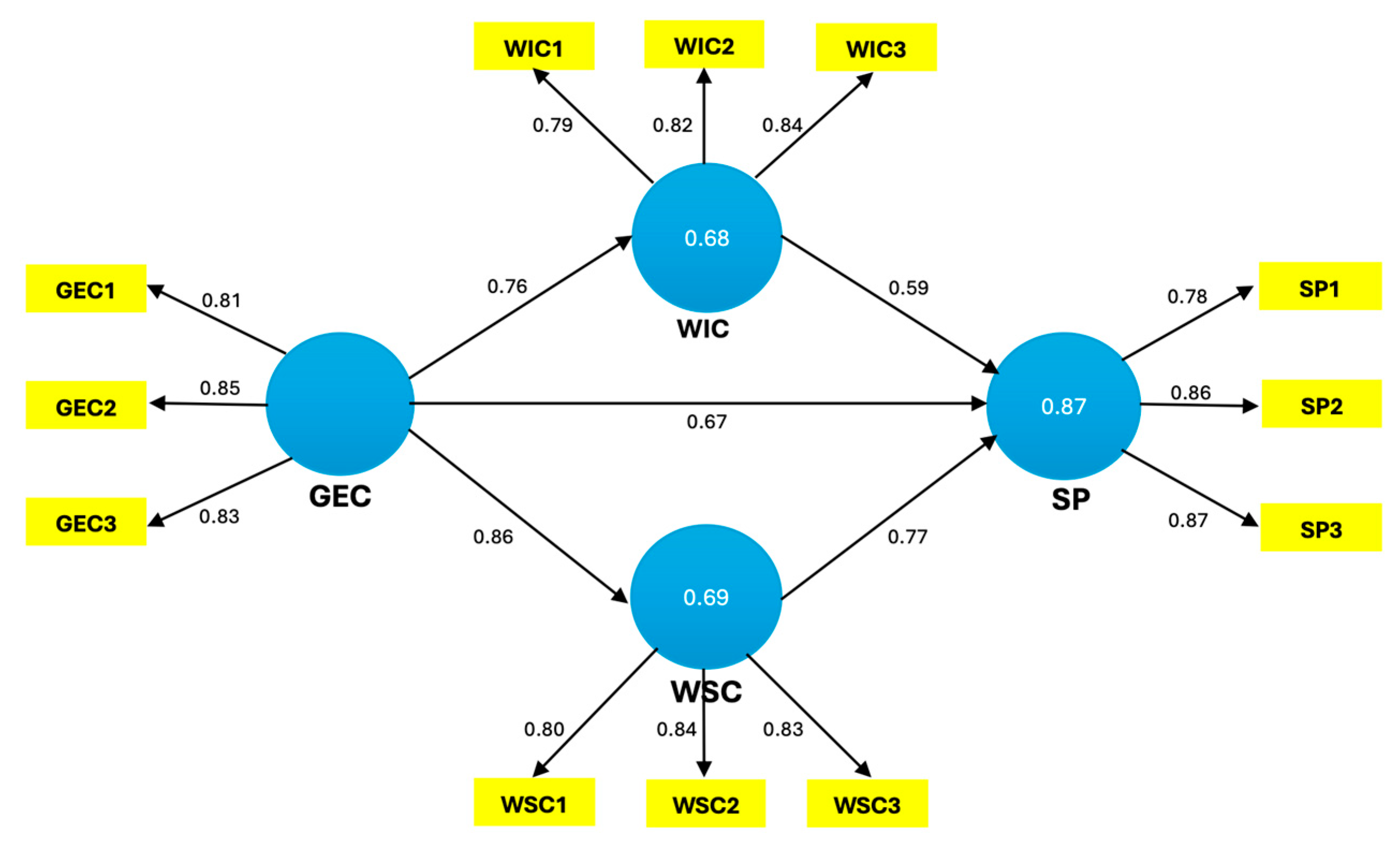

| Construct | Indicator | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEC | GEC1 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.68 |

| GEC2 | 0.85 | ||||

| GEC3 | 0.83 | ||||

| WIC | WIC1 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.65 |

| WIC2 | 0.82 | ||||

| WIC3 | 0.84 | ||||

| WSC | WSC1 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.67 |

| WSC2 | 0.84 | ||||

| WSC3 | 0.83 | ||||

| SP | SP1 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.73 |

| SP2 | 0.86 | ||||

| SP3 | 0.87 |

| Construct | GEC | WIC | WSC | SP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEC | 0.82 | |||

| WIC | 0.54 | 0.81 | ||

| WSC | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.82 | |

| SP | 0.46 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.85 |

| Construct | GEC | WIC | WSC | SP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEC | - | |||

| WIC | 0.65 | - | ||

| WSC | 0.61 | 0.63 | - | |

| SP | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.69 | - |

| Path | β | t-Value | p-Value | R2 | Adjusted R2 | f2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEC → WIC | 0.42 | 8.21 | 0.000 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.19 | 0.31 |

| GEC → SP | 0.18 | 2.35 | 0.019 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.28 |

| GEC → WSC | 0.39 | 7.58 | 0.000 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.29 |

| WIC → SP | 0.34 | 5.41 | 0.000 | 0.21 | |||

| WSC → SP | 0.36 | 6.02 | 0.000 | 0.24 |

| Indirect Effect | β | t-Value | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEC → WIC → SP | 0.14 | 3.27 | 0.001 | Significant |

| GEC → WSC → SP | 0.16 | 3.81 | 0.000 | Significant |

| Test | Result | Threshold | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harman’s Single-Factor | 32% variance explained | <50% | No CMB issue |

| Full Collinearity VIF | All values < 3.3 | <3.3 | No CMB issue |

| Construct | Indicator | Q2_Predict | RMSE (PLS) | RMSE (LM) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WIC | WIC1 | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.48 | Better predictive power |

| WIC2 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.50 | ||

| WIC3 | 0.20 | 0.44 | 0.49 | ||

| WSC | WSC1 | 0.23 | 0.40 | 0.47 | Better predictive power |

| WSC2 | 0.20 | 0.43 | 0.49 | ||

| WSC2 | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.48 | ||

| SP | SP1 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0.46 | Better predictive power |

| SP2 | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0.47 | ||

| SP3 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tahir, T.; Hasan, M.; Thamrin Tahir, M.I.; Ampa, A.T.; To Tadampali, A.C.; Suharto, R.; Ahmad, M.I.S. From Gendered Entrepreneurial Cognition to Sustainable Performance: The Power of Women’s Entrepreneurial Capital in Emerging Economies. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110433

Tahir T, Hasan M, Thamrin Tahir MI, Ampa AT, To Tadampali AC, Suharto R, Ahmad MIS. From Gendered Entrepreneurial Cognition to Sustainable Performance: The Power of Women’s Entrepreneurial Capital in Emerging Economies. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):433. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110433

Chicago/Turabian StyleTahir, Thamrin, Muhammad Hasan, Muhammad Ilyas Thamrin Tahir, Andi Tenri Ampa, Andi Caezar To Tadampali, Ratnah Suharto, and Muhammad Ihsan Said Ahmad. 2025. "From Gendered Entrepreneurial Cognition to Sustainable Performance: The Power of Women’s Entrepreneurial Capital in Emerging Economies" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110433

APA StyleTahir, T., Hasan, M., Thamrin Tahir, M. I., Ampa, A. T., To Tadampali, A. C., Suharto, R., & Ahmad, M. I. S. (2025). From Gendered Entrepreneurial Cognition to Sustainable Performance: The Power of Women’s Entrepreneurial Capital in Emerging Economies. Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110433