Corporate Culture, Leadership, and Pathological Relationships: A Moderated Mediation Model of Employees’ Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Corporate Culture and Working Atmosphere

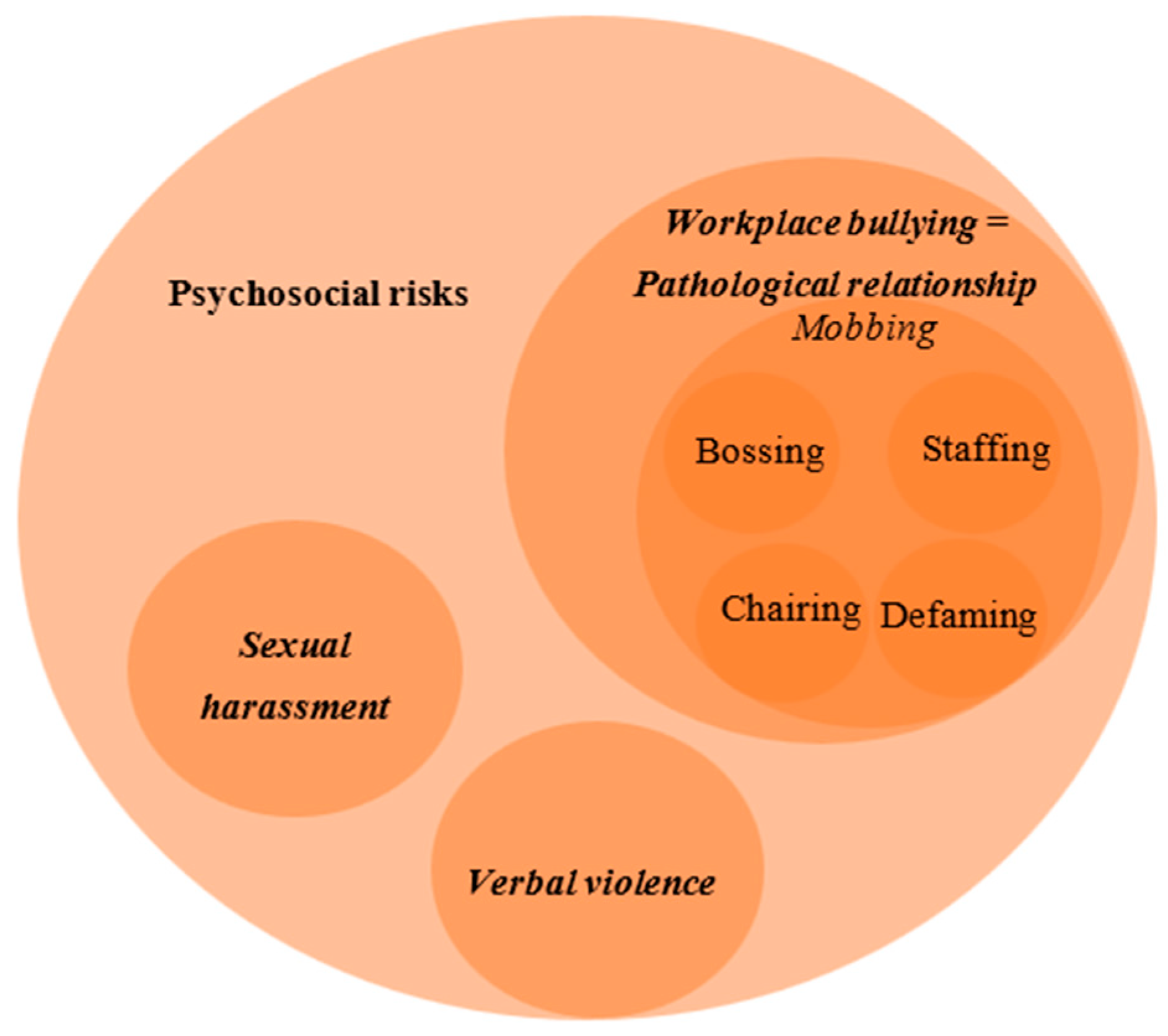

2.2. Pathological Relationships

2.3. Leadership

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sample Size

3.2. Ethical Considerations

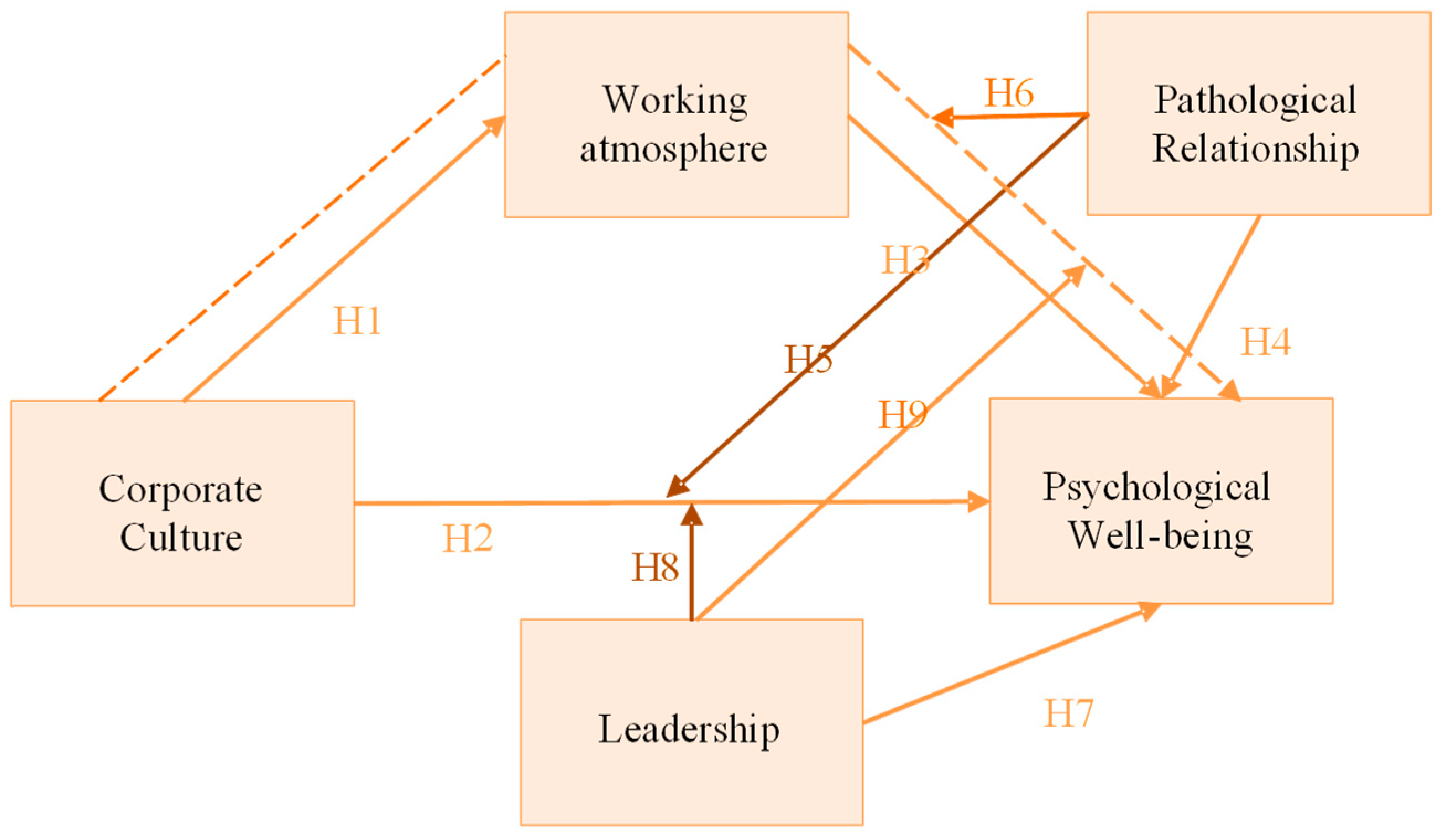

3.3. Moderated Mediation

3.4. Assumptions of Moderated Mediation

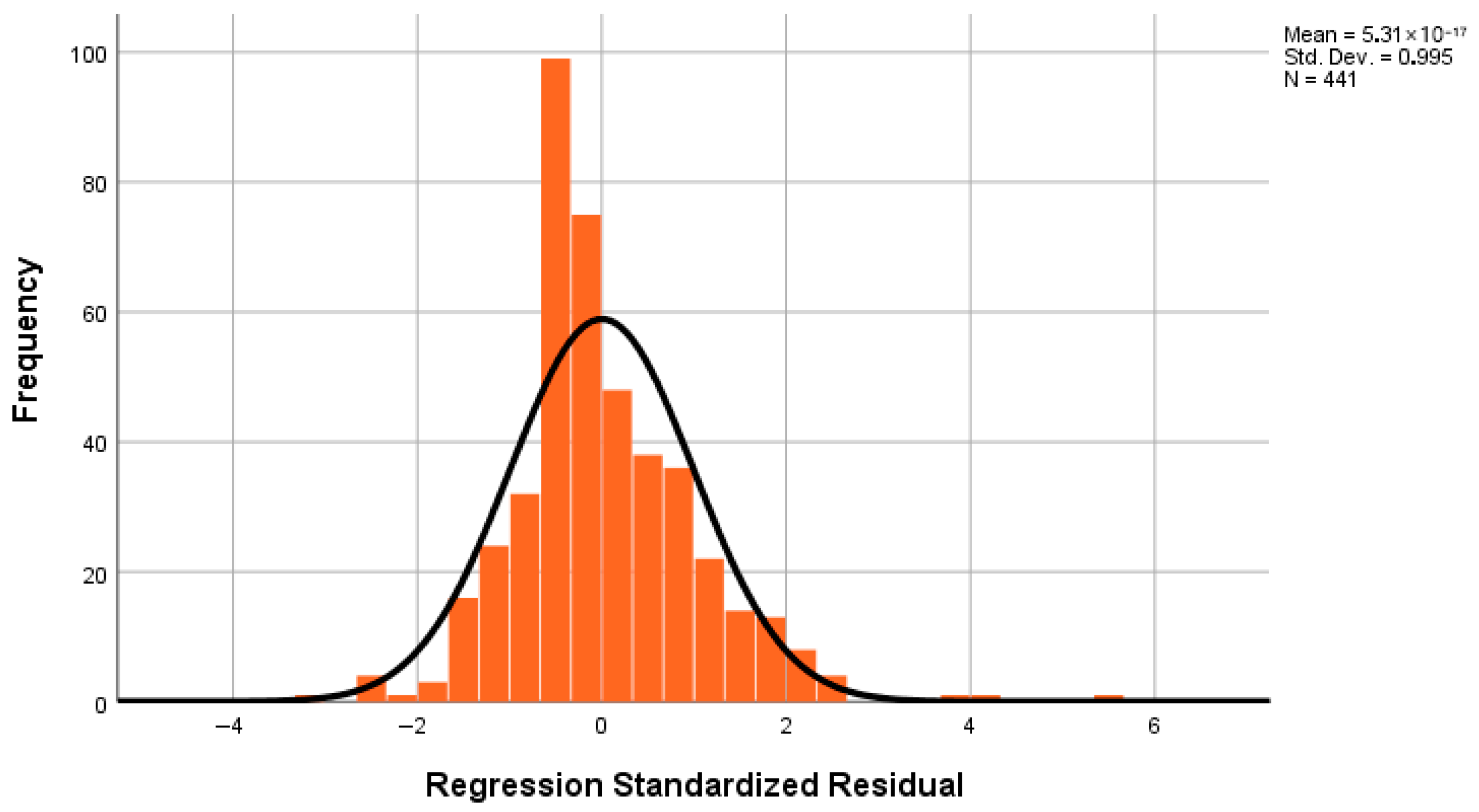

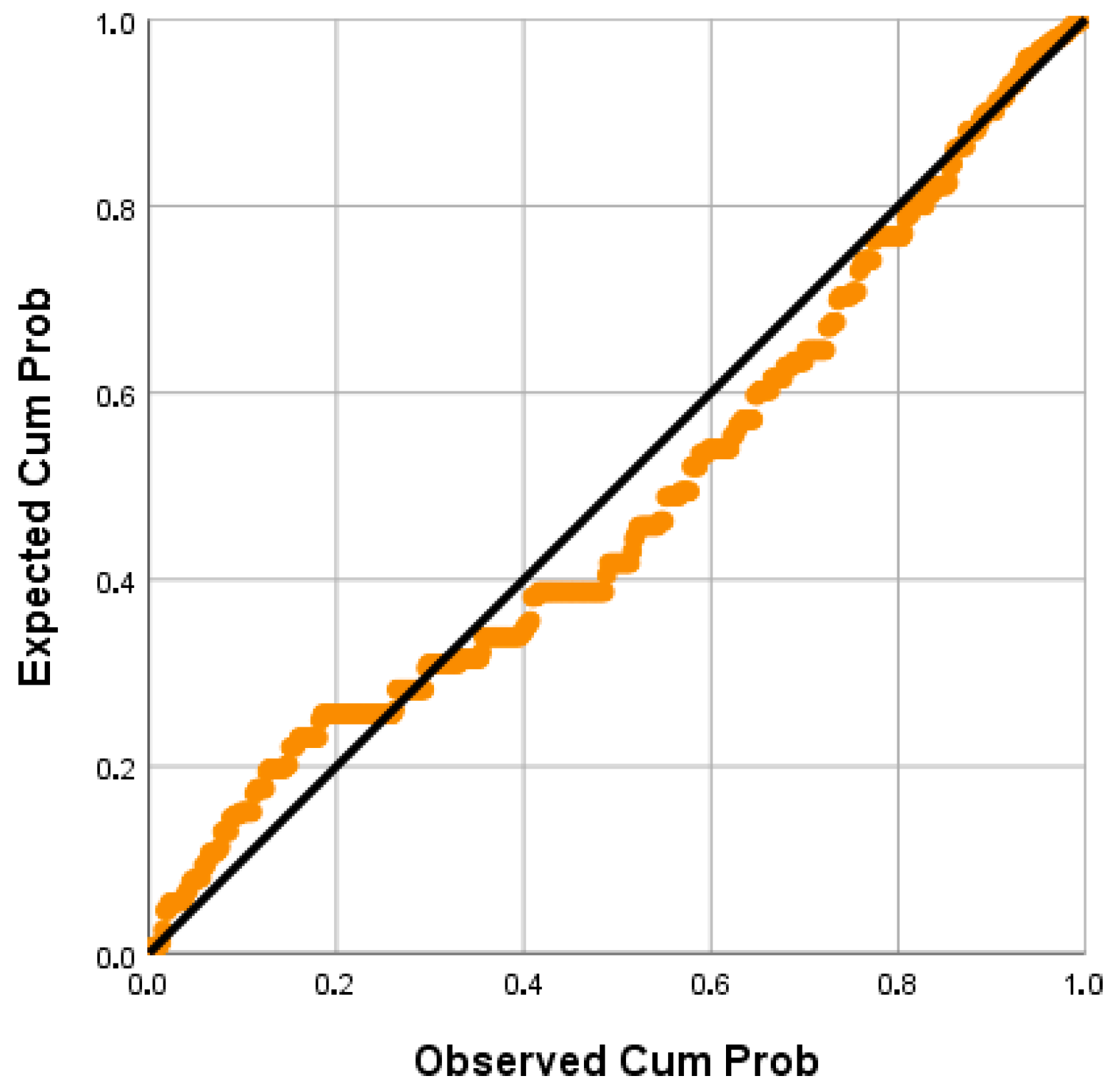

3.4.1. Normal Distribution

3.4.2. Homoscedasticity of Error Values

3.5. Data Analysis

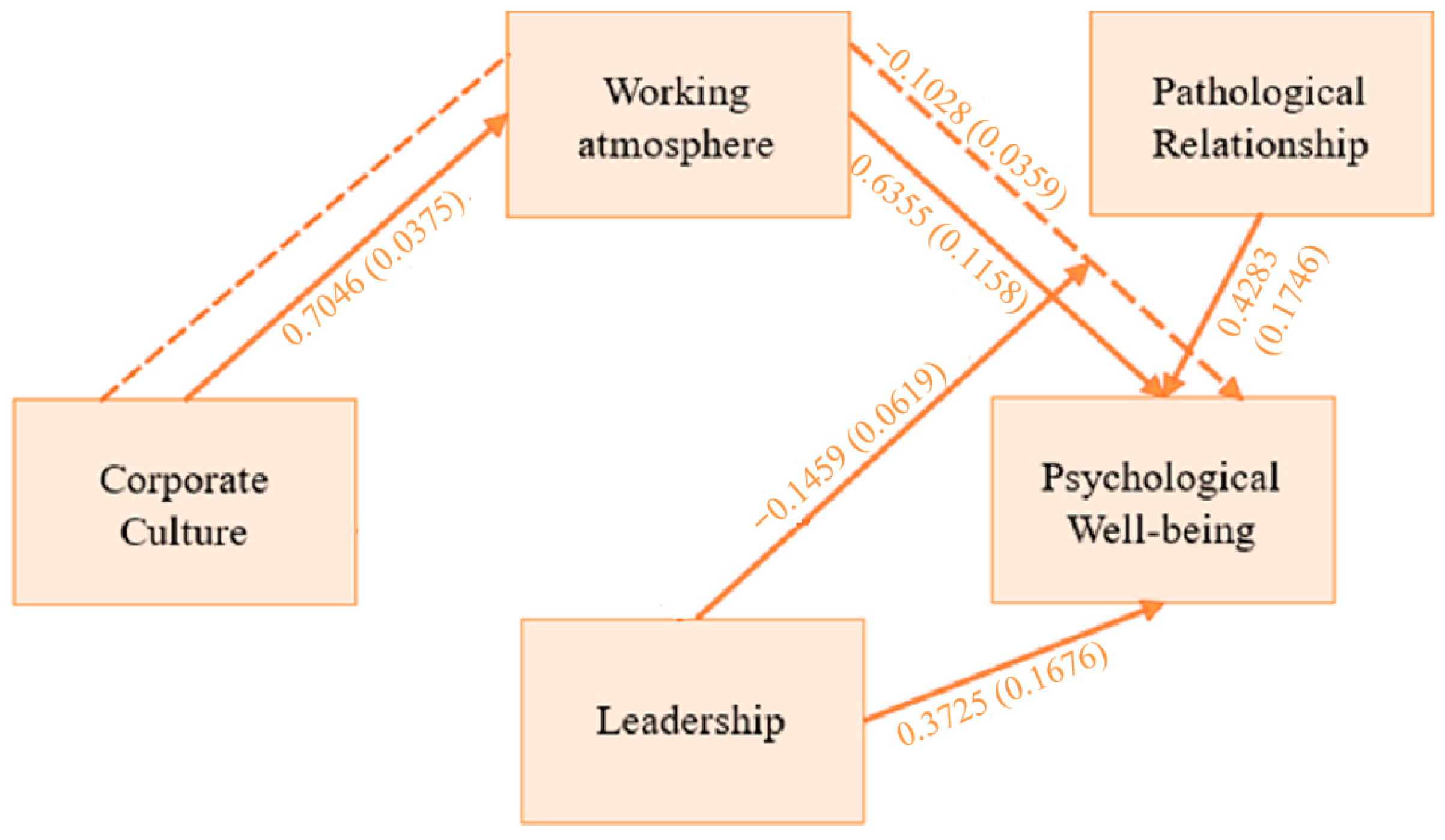

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Framework

5.2. The Impact of Corporate Culture and Work Atmosphere on Psychological Well-Being

5.3. Pathological Relationships and Their Complex Impact on Psychological Well-Being

5.4. The Role of Leadership in Promoting Psychological Well-Being

5.5. Interpretation of Rejected Hypotheses

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.2.1. Leadership Development

6.2.2. Corporate Culture Reform

6.2.3. Working Climate Interventions

6.3. Limitations and Uniqueness of Research

6.3.1. Methodological Limitations

6.3.2. Sample and Context Limitations

6.3.3. Interpretational Complexity

6.4. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LWMS | Luxembourg Workplace Mobbing Scale |

| LLCI | Lower Limit of the Confidence Interval |

| ULCI | Upper Limit of the Confidence Interval |

| SE | Standard Error |

| SK NACE | Slovak Nomenclature of Economic Activities |

| Coeff | Unstandardized regression coefficient (b) |

References

- Abraham, I. L., & Foley, T. S. (1984). The work environment scale and the ward atmosphere scale (short forms): Psychometric data. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 58(1), 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S., Singh, N., & Kumar, D. (2020). Impact of organizational culture on work–Life-balance. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, 1(8), 264–267. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S., Sohal, A. S., & Wolfram Cox, J. (2020). Leading well is not enough: A new insight from the ethical leadership, workplace bullying and employee well-being relationships. European Business Review, 32(2), 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikens, K. A., Astin, J., Pelletier, K. R., Levanovich, K., Baase, C. M., Park, Y. Y., & Bodnar, C. M. (2014). Mindfulness goes to work: Impact of an online workplace intervention. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56(7), 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alipour, L., & Khoramian, M. (2023). Investigating the impact of biophilic design on employee performance and well-being by designing a research instrument. Kybernetes, 53(11), 4431–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annor, F., & Amponsah-Tawiah, K. (2020). Relationship between workplace bullying and employees’ subjective well-being: Does resilience make a difference? Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 32(3), 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristidou, L., Mpouzika, M., Papathanassoglou, E. D., Middleton, N., & Karanikola, M. N. (2020). Association between workplace bullying occurrence and trauma symptoms among healthcare professionals in Cyprus. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(11), 575623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, K. A. (2017). Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K. A., Turner, N., Barling, J., Kelloway, E. K., & McKee, M. C. (2007). Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: The mediating role of meaningful work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(3), 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auweiler, L., Lang, J., Thissen, M., & Pauli, R. (2023). Workplace bullying experience predicts same-day affective rumination but not next morning mood: Results from a moderated mediation analysis based on a one-week daily diary study. Sustainability, 15(21), 15410. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, A. (2022). Impact of psychological well-being on job performance of employees. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4788728 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Barling, J., & Frone, M. R. (2017). If only my leader would just do something! Passive leadership undermines employee well-being through role stressors and psychological resource depletion. Stress and Health, 33(3), 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Bau, F., & Wagner, K. (2015). Measuring corporate entrepreneurship culture. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 25(2), 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, T. A. (2011). Direct and indirect links between organizational work–home culture and employee well-being. British Journal of Management, 22(2), 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. R. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(2), 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommakanti, S. M., & Swamy, T. N. V. R. (2024). Unraveling the ethical fabric: Exploring the influence of organizational ethical climate on employee psychological well-being. In Diversity, equity and inclusion (pp. 94–111). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Borairi, S., Deneault, A. A., Madigan, S., Fearon, P., Devereux, C., Geer, M., Jeyanayagam, B., Martini, J., & Jenkins, J. (2024). A meta-analytic examination of sensitive responsiveness as a mediator between depression in mothers and psychopathology in children. Attachment & Human Development, 26(4), 273–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M., & Batinic, B. (2002). Understanding the willingness to participate in online surveys: The case of e-mail questionnaires. Online Social Sciences, 81, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Branch, S., Ramsay, S., & Barker, M. (2013). Workplace bullying, mobbing and general harassment: A review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(3), 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressani, M., & Sprecher, A. (2019). Atmospheres. Journal of Architectural Education, 73(1), 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, P., Timms, C., Siu, O. L., Kalliath, T., O’Driscoll, M. P., Sit, C. H., Lo, D., & Lu, C. Q. (2013). Validation of the Job Demands-Resources model in cross-national samples: Cross-sectional and longitudinal predictions of psychological strain and work engagement. Human Relations, 66(10), 1311–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Búgelová, T. (2002). Komunikácia v škole a rodine. Prešovská univerzita. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty, S. (2014). Leadership: Validation of a self-report scale: Comment on dussault, frenette, and fernet (2013). Psychological Reports, 115(2), 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R. (2024). The impact of employees’ health and well-being on job performance. Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, 29(1), 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernukh, D. (2022). Corporate culture of the enterprise: Essence, models, types. Екoнoмічний вісник Дoнбасу, 4(70), 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S. C. (2001). Work cultures and work/family balance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(3), 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E., Näswall, K., Masselot, A., & Malinen, S. (2025). Feeling safe to speak up: Leaders improving employee wellbeing through psychological safety. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 46(1), 152–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colarossi, D. V. (2012). Development of a measure of Corporate Safety Culture for the transportation industry. University of Denver. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, M. F., Searle, B. J., Kangas, M., & Nwiran, Y. (2019). How resilience is strengthened by exposure to stressors: The systematic self-reflection model of resilience strengthening. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 32(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cribari-Neto, F. (2004). Asymptotic inference under heteroskedasticity of unknown form. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 45(2), 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C. (2005). The application of Ryff’Psychologcal well-being scale in college students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 19(2), 128. [Google Scholar]

- Curral, L., Carmona, L., Pinheiro, R., Reis, V., & Chambel, M. J. (2023). The effect of leadership style on firefighters well-being during an emergency. Fire, 6(6), 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, E. I., van der Meulen, R. T., de Wandeler, J., Zijlstra, B. J., Formsma, A. R., & Bögels, S. M. (2020). The Unilever study: Positive effects on stress and risk for dropout from work after the finding peace in a frantic world training. Mindfulness, 11, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffuant, G., Roubin, T., Nugier, A., & Guimond, S. (2024). A newly detected bias in self-evaluation. PLoS ONE, 19(2), e0296383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devonish, D. (2013). Workplace bullying, employee performance and behaviors: The mediating role of psychological well-being. Employee Relations, 35(6), 630–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, R. K., & Sjabadhymi, B. (2021). Digital leadership as a resource to enhance managers’ psychological well-being in COVID-19 pandemic situation in Indonesia. The South East Asian Journal of Management, 15(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dextras-Gauthier, J., Gilbert, M. H., Dima, J., & Adou, L. B. (2023). Organizational culture and leadership behaviors: Is manager’s psychological health the missing piece? Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1237775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H., Yu, E., & Li, Y. (2020). Transformational leadership and core self-evaluation: The roles of psychological well-being and supervisor-subordinate guanxi. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 30(3), 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dujo López, V., González Trijueque, D., Graña Gómez, J. L., & Andreu Rodríguez, J. M. (2020). A psychometric study of a Spanish version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised: Confirmatory factor analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T., & Sumartojo, S. (2015). Designing atmospheres: Introduction to special issue. Visual Communication, 14(3), 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Els, B., & Jacobs, M. (2023). Unravelling the interplay of authentic leadership, emotional intelligence, cultural intelligence and psychological well-being. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 49, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkutlu, H., & Chafra, J. (2016). Benevolent leadership and psychological well-being: The moderating effects of psychological safety and psychological contract breach. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 37(3), 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, S., Mokhtar, D., Ng, K., & Niven, K. (2023). What influences the relationship between workplace bullying and employee well-being? A systematic review of moderators. Work & Stress, 37(3), 345–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiabane, E., Flachi, D., Giorgi, I., Crepaldi, I., Candura, S. M., Mazzacane, F., & Argentero, P. (2015). Professional outcomes and psychological health after workplace bullying: An exploratory follow-up study. La Medicina del Lavoro, 106(4), 271–283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Finchilescu, G., Bernstein, C., & Chihambakwe, D. (2019). The impact of workplace bullying in the Zimbabwean nursing environment: Is social support a beneficial resource in the bullying–well-being relationship? South African Journal of Psychology, 49(1), 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finsel, J., Wöhrmann, A., Wang, M., Wilckens, M., & Deller, J. (2021). Organizational practices for the aging workforce: Validation of an English version of the later life workplace index. Innovation in Aging, 5(Suppl. S1), 826–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finstad, G. L., Giorgi, G., Lulli, L. G., Pandolfi, C., Foti, G., León-Perez, J. M., Cantero-Sánchez, F. J., & Mucci, N. (2021). Resilience, coping strategies and posttraumatic growth in the workplace following COVID-19: A narrative review on the positive aspects of trauma. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganassali, S. (2008). The influence of the design of web survey questionnaires on the quality of responses. Survey Research Methods, 2(1), 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gatt, J. M., Burton, K. L., Schofield, P. R., Bryant, R. A., & Williams, L. M. (2014). The heritability of mental health and wellbeing defined using COMPAS-W, a new composite measure of wellbeing. Psychiatry Research, 219(1), 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S., & Srivastava, B. K. (2014). Construction of a reliable and valid scale for measuring organizational culture. Global Business Review, 15(3), 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J. R., Grennan, J., Harvey, C. R., & Rajgopal, S. (2022). Corporate culture: Evidence from the field. Journal of Financial Economics, 146(2), 552–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesiuk, L., Szymańska, A., Jastrzębska, J., & Rutkowska, M. (2022). The relationship between the manifestations of mobbing and reactions of mobbing victims. Medycyna Pracy, 73(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R., & Bakhshi, A. (2018). Workplace bullying and employee well-being: A moderated mediation model of resilience and perceived victimization. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 33(2), 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, J., Huhtamäki, F., Sundvik, D., & Thor, T. (2024). Nothing to fear: Strong corporate culture and workplace safety. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 63(2), 519–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabi, R., & Kumral, M. (2022). Addressing specific safety and occupational health challenges for the Canadian mines located in remote areas where extreme weather conditions dominate. Journal of Sustainable Mining, 21(3), 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C. C., Chen, H., Yang, N., Wang, X. H. F., & Wang, B. L. (2023). Empowering leadership and leader’s psychological well-being: A moderated mediation model. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 51(5), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanein, A., & Elrayah, M. (2025). Empowering minds in the hospitality sector: The moderation-mediation role of psychological empowerment in fostering transformational leadership and psychological well-being. Journal of Posthumanism, 5(5), 2944–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassi, A., & Storti, G. (2023). Wise leadership: Construction and validation of a scale. Modern Management Review, 28(1), 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A., & Afshari, L. (2021). Supportive organizational climate: A moderated mediation model of workplace bullying and employee well-being. Personnel Review, 50(7/8), 1685–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (1989). Organising for cultural diversity. European Management Journal, 7(4), 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtman, I., Jettinghoff, K., & Cedillo, L. (2007). Protecting Workers’ Health Series No. 6: Raising awareness of stress at work in developing countries. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, N. H., Lange, B., Rodin, D., & Wolf-Bauwens, M. L. (2018). Getting clear on corporate culture: Conceptualisation, measurement and operationalisation. Journal of the British Academy, 6(1), 155–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F. S., Liu, Y. A., & Tsaur, S. H. (2019). The impact of workplace bullying on hotel employees’ well-being: Do organizational justice and friendship matter? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1702–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J. G. (1999). Transformational/charismatic leadership’s tranformation of the field: An historical essay. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inceoglu, I., Thomas, G., Chu, C., Plans, D., & Gerbasi, A. (2018). Leadership behavior and employee well-being: An integrated review and a future research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M., Majeed, M., & Khattak, S. A. (2021). The combined effect of safety specific transformational leadership and safety consciousness on psychological well-being of healthcare workers. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 688463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L. R., & Brett, J. M. (1984). Mediators, moderators, and tests for mediation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(2), 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, S., & Majeed, N. (2019). Relationship between team culture and team performance through lens of knowledge sharing and team emotional intelligence. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(1), 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D., Aggarwal, S., Robinson, J., Kumar, N., Spearot, A., & Park, D. S. (2022). Exhaustive or exhausting? Evidence on respondent fatigue in long surveys. Journal of Development Economics, 161, 102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalliath, T. J., Bluedorn, A. C., & Strube, M. J. (1999). A test of value congruence effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20(7), 1175–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, F., Li, J., & Hua, Y. (2023). How and when does humble leadership enhance newcomer well-being. Personnel Review, 52(1), 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A., Husain, S., Minhaj, S. M., Ali, M. A., & Helmi, M. A. (2024). To explore the impact of corporate culture and leadership behaviour on work performance, mental health and job satisfaction of employees: An empirical study. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(11), 6417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H., Choi, H. J., Yu, J. P., Lim, J. H., Lee, H. J., & Jung, S. H. (2020). Argumentum ad hominem and coercive company culture influences on workaholism: Results and implications of a cross-cultural South Korea study. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 30(2), 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, M., Willard-Grace, R., Huang, B., & Grumbach, K. (2018). Maslach burnout inventory and a self-defined, single-item burnout measure produce different clinician and staff burnout estimates. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(8), 1344–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, M., & Keklik, İ. (2020). Predicting psychological well-being levels of research assistants working at Hacettepe University. Hacettepe Universitesi Egitim Fakultesi Dergisi-Hacettepe University Journal of Education, 35(1), 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kubáni, V. (2011). Psychológia práce. Prešovská Univerzita. [Google Scholar]

- Kudryavtseva, A., Sklemina, D., Vereitinova, T., Dmitrieva, V., & Kislyakov, P. (2018). Organizational environment as factor of psychological well-being. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 50, 642–650. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose, V., S, S., Wilson, P. R., & MR, A. (2019). The differential association of workplace conflicts on employee well-being: The moderating role of perceived social support at work. International Journal of Conflict Management, 30(5), 680–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R., Dollard, M. F., Tuckey, M. R., & Dormann, C. (2011). Psychosocial safety climate as a lead indicator of workplace bullying and harassment, job resources, psychological health and employee engagement. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 43(5), 1782–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipold, B., Munz, M., & Michele-Malkowsky, A. (2019). Coping and resilience in the transition to adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 7(1), 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesener, T., Gusy, B., & Wolter, C. (2019). The job demands-resources model: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work & Stress, 33(1), 76–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lindert, L., Zeike, S., Choi, K., & Pfaff, H. (2022). Transformational leadership and employees’ psychological wellbeing: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, W. W., Moerkerke, B., Loeys, T., & Vansteelandt, S. (2022). Disentangling indirect effects through multiple mediators without assuming any causal structure among the mediators. Psychological Methods, 27(6), 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorincová, S., Bajzíková, L., Oborilová, I., & Hitka, M. (2020). Corporate culture in small and meduium-sized enterprises of forestry and forest-based industry is different. Acta Facultatis Xylologiae Zvolen, 62, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, K. B., Kroeck, K. G., & Sivasubramaniam, N. (1996). Effectiveness correlates of transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic review of the MLQ literature. The Leadership Quarterly, 7(3), 385–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manotas, E. M. A. (2015). Mobbing in organizations: Analysis of particular cases in a higher education institution. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191, 1607–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, H., Pyun, D. Y., Md Husin, M., Gholami Torkesaluye, S., & Rouzfarakh, A. (2022). The influences of authentic Leadership, meaningful work, and perceived organizational support on psychological well-being of employees in sport organizations. Journal of Global Sport Management, 9(3), 575–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A. S., Lucke, C. M., Nelson, K. M., & Stallworthy, I. C. (2021). Resilience in development and psychopathology: Multisystem perspectives. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 17(1), 521–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, I. (2010). Measures of self-perceived well-being. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(1), 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, L., Keller, A., Reis, D., & Nohe, C. (2023). On the asymmetry of losses and gains: Implications of changing work conditions for well-being. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(8), 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhuber, S. (2020). Deconstructing impoliteness in professional discourse: The social psychology of workplace mobbing. A cross-disciplinary contribution with conclusions for the intercultural workplace. Lodz Papers in Pragmatics, 16(2), 235–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N., & Dibb, S. (2006). Using email questionnaires for research: Good practice in tackling non-response. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 14, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michulek, J. (2021). Porovnanie právnej úpravy patologických vzťahov na pracovisku v Slovenskej republike a vybraných krajinách Európskej únie. PHD Progress, 9(1), 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Michulek, J., Gajanova, L., Krizanova, A., & Nadanyiova, M. (2023). Determinants of improving the relationship between corporate culture and work performance: Illusion or reality of serial mediation of leadership and work engagement in a crisis period? Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1135199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michulek, J., Gajanova, L., Sujanska, L., & Nahalkova Tesarova, E. (2024). Understanding how workplace dynamics affect the psychological well-being of university teachers. Aministrative Sciences, 14(12), 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minárová, M., Benčiková, D., Malá, D., & Smutný, F. (2020, October 9–10). Mobbing in a workplace and its negative influence on building quality culture. 19th International Scientific Conference Globalization and its Socio-Economic Consequences 2019—Sustainability in the Global-Knowledge Economy (Vol. 74, p. 05014), Rajecké Teplice, Slovakia. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, E., & Joseph, J. (2023). A review on the impact of workplace culture on employee mental health and well-being. International Journal of Case Studies in Business, IT and Education (IJCSBE), 7(2), 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhonen, T., Jönsson, S., Denti, L., & Chen, K. (2013). Social climate as a mediator between leadership behavior and employee well-being in a cross-cultural perspective. Journal of Management Development, 32(10), 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murry, V. M., Nyanamba, J. M., Hanebutt, R., Debreaux, M., Gastineau, K. A., Goodwin, A. K., & Narisetti, L. (2023). Critical examination of resilience and resistance in African American families: Adaptive capacities to navigate toxic oppressive upstream waters. Development and Psychopathology, 35(5), 2113–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthuswamy, V. V., & Li, H. X. (2023). Abusive leadership mitigates psychological well-being and increases presenteeism: Exploration of the negative effects of abusive leadership on employees? mental health. American Journal of Health Behavior, 47(3), 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuert, C. E. (2021). The effect of question positioning on data quality in web surveys. Sociological Methods & Research, 53(1), 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J. E. (1977). Development of a measure of perceived work environment (PWE). Academy of Management Journal, 20(4), 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C. K. J., Kwan, L. Y. J., & Chan, W. (2024). A note on evaluating the moderated mediation effect. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 31(2), 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K., & Daniels, K. (2012). Does shared and differentiated transformational leadership predict followers’ working conditions and well-being? The Leadership Quarterly, 23(3), 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K., Yarker, J., Randall, R., & Munir, F. (2009). The mediating effects of team and self-efficacy on the relationship between transformational leadership, and job satisfaction and psychological well-being in healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(9), 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okechukwu, F. O., Ogba, K. T., Nwufo, J. I., Ogba, M. O., Onyekachi, B. N., Nwanosike, C. I., & Onyishi, A. B. (2022). Academic stress and suicidal ideation: Moderating roles of coping style and resilience. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, P., Uchida, T., Magnier-Watanabe, R., Benton, C., & Nagata, K. (2024). Antecedents of subjective well-being at work–The case of French permanent employees. Evidence-based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 12(4), 1040–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ökdem, M. (2023). Mobbing used against teachers by school administrators: Examples of case. Hacettepe Universitesi Egitim Fakultesi Dergisi-Hacettepe University Journal of Education, 38, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. G., Kim, J. S., Yoon, S. W., & Joo, B. K. (2017). The effects of empowering leadership on psychological well-being and job engagement: The mediating role of psychological capital. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(3), 350–367. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S. L., Jimmieson, N. L., Walsh, A. J., & Loakes, J. L. (2015). Trait resilience fosters adaptive coping when control opportunities are high: Implications for the motivating potential of active work. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(3), 583–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecino, V., Mañas, M. A., Díaz-Fúnez, P. A., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Padilla-Góngora, D., & López-Liria, R. (2019). Organisational climate, role stress, and public employees’ job satisfaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(10), 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perko, K., Kinnunen, U., Tolvanen, A., & Feldt, T. (2016). Investigating occupational well-being and leadership from a person-centred longitudinal approach: Congruence of well-being and perceived leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(1), 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, Ş. C., Ştefan, S. C., Olariu, A. A., Popa, C. F., & Pantea, M. I. (2023). Shaping the culture of your organization by the human capital: Employees’ competencies and leaders’ perceived behavior. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 24(5), 1164–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posthuma, A. B. (1970). Normative data on the least-preferred co-worker scale (LPC) and the group atmosphere questionnaire (GA) (No. TR708).

- Postrelova, M. N. (2019). Transforming corporate culture of south Korea in a new socio-eco-nomic environment. Korean Peninsula in Search for Peace and Prosperity, 1, 261. [Google Scholar]

- Pozega, Z., Crnkovic, B., & Gashi, L. M. (2013). Value dimensions of corporate culture of state-owned enterprise employees. Ekonomski vjesnik: Review of Contemporary Entrepreneurship, Business, and Economic Issues, 26(2), 391–399. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, W., & Saufi, A. (2025). Impact of corporate culture towards employee belongingness: An analysis of the literature. International Journal of Scientific Multidisciplinary Research, 3(2), 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raithel, K., van Knippenberg, D., & Stam, D. (2021). Team leadership and team cultural diversity. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 28(3), 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasak, N. T. S., Zamri, M. N., Suhaimi, M. H., & Kamaruddin, K. (2024). The role of leadership styles, work-life balance and the physical environment in promoting psychological well-being: A job demands-resources perspective. Information Management and Business Review, 16(3), 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattrie, L. T., Kittler, M. G., & Paul, K. I. (2020). Culture, burnout, and engagement: A meta-analysis on national cultural values as moderators in JD-R theory. Applied Psychology, 69(1), 176–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N., Semedo, A. S., Gomes, D., Bernardino, R., & Singh, S. (2022). The effect of workplace bullying on burnout: The mediating role of affective well-being. Management Research Review, 45(6), 824–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieder, A. D., Roth, S. L., Musyimi, C., Ndetei, D., Sassi, R. B., Mutiso, V., Hall, G. B., & Gonzalez, A. (2019). Impact of maternal adverse childhood experiences on child socioemotional function in rural Kenya: Mediating role of maternal mental health. Developmental Science, 22(5), e12833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodic, V. (2015, November 12–13). Mobbing in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the member states of the European Union. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 144, p. 012016), Baia Mare, Romania. [Google Scholar]

- Roskams, M., & Haynes, B. (2021). Environmental demands and resources: A framework for understanding the physical environment for work. Facilities, 39(9/10), 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, G., & Lees, B. (2001). Developing corporate culture as a competitive advantage. Journal of Management Development, 20(10), 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samul, J. (2024). Spiritual leadership and work engagement: A mediating role of spiritual well-being. Central European Management Journal, 32(3), 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A. (2025). Self-dignity amidst adversity: A review of coping strategies in the face of workplace toxicity. Management Review Quarterly, 75(1), 881–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. (2015). Engaging leadership in the job demands-resources model. Career Development International, 20(5), 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieman, S., & Reid, S. (2008). Job authority and interpersonal conflict in the workplace. Work and Occupations, 35(3), 296–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y. X. (2023). The influence of sports on the psychological state of employees from the perspective of the corporate culture. Revista de Psichologia del Deporte, 32(3), 310–319. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, J. Y. Y., Mustamil, N. M., & Wider, W. (2023). Psychosocial working conditions and work engagement: The mediating role of psychological well-being. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 17(4), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjögren, T., Nissinen, K. J., Järvenpää, S. K., Ojanen, M. T., Vanharanta, H., & Mälkiä, E. A. (2006). Effects of a physical exercise intervention on subjective physical well-being, psychosocial functioning and general well-being among office workers: A cluster randomized-controlled cross-over design. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 16(6), 381–390. [Google Scholar]

- Sprigg, C. A., Niven, K., Dawson, J., Farley, S., & Armitage, C. J. (2019). Witnessing workplace bullying and employee well-being: A two-wave field study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(2), 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevičienė, A., Tamaševičius, V., Diskienė, D., Grakauskas, Ž., & Rudinskaja, L. (2021). The mediating effect of work-life balance on the relationship between work culture and employee well-being. Business Economics and Management (JBEM), 22(4), 988–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffgen, G., Sischka, P., Schmidt, A. F., Kohl, D., & Happ, C. (2016). The Luxembourg workplace mobbing scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(2), 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švábová, L., Ďurana, P., & Ďurica, M. (2022). Deskriptívna a induktívna štatistika (1st ed.). EDIS-Vydavateľstvo UNIZA. [Google Scholar]

- Tempel, J., Prause, I., & Heinz, R. (2004, October 18–20). Working atmosphere, work demands and work ability of the workforce in successful retail markets. International Congress Series (Vol. 1280, pp. 316–321), Verona, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Tummers, L. G., & Bakker, A. B. (2021). Leadership and job demands-resources theory: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 722080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungar, M. (2013). Resilience, trauma, context, and culture. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 14(3), 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandekerckhove, S., Lenaerts, K., Szekér, L., Desiere, S., Lamberts, M., & Ramioul, M. (2021). Musculoskeletal disorders and psychosocial risk factors in the workplace—Statistical analysis of EU-wide survey data. Musculoskeletal disorders and psychosocial risk factors in the workplace—Statistical analysis of EU-wide survey data. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). [Google Scholar]

- Vernimmen, G., Gadassi-Polack, R., Bronstein, M. V., De Putter, L., & Everaert, J. (2025). Social interpretation bias and inflexibility: Mapping indirect pathways from pathological personality traits to symptom clusters of anxiety and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 233, 112920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkey, F. H., & McCormick, I. A. (1985). Multiple replication of factor structure: A logical solution for a number of factors problem. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 20(1), 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. J., Demerouti, E., & Le Blanc, P. (2017). Transformational leadership, adaptability, and job crafting: The moderating role of organizational identification. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 100, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., & Preacher, K. J. (2015). Moderated mediation analysis using Bayesian methods. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(2), 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. F., & Lin, Q. G. (2007, June 1–3). The development of innovative corporate culture for enterprises to promote technology innovation. Managing Total Innovation and Open Innovation in the 21st Century (Vol. 1–2, pp. 1243–1247), Hangzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., & Hudy, M. J. (1997). Overall job satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M., Razinskas, S., Backmann, J., & Hoegl, M. (2018). Authentic leadership and leaders’ mental well-being: An experience sampling study. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(2), 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weziak-Bialowolska, D., Lee, M. T., Cowden, R. G., Bialowolski, P., Chen, Y., VanderWeele, T. J., & McNeely, E. (2023). Psychological caring climate at work, mental health, well-being, and work-related outcomes: Evidence from a longitudinal study and health insurance data. Social Science & Medicine, 323, 115841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. (2014). Researching and developing mental health and well-being assessment tools for supporting employers and employees in Wales [Doctoral dissertation, Cardiff University]. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G., & Smith, A. P. (2016). Using single-item measures to examine the relationships between work, personality, and well-being in the workplace. Psychology, 7, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A. M. (2001). Understanding organisational culture and the implications for corporate marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 35(3–4), 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodrow, C., & Guest, D. E. (2017). Leadership and approaches to the management of workplace bullying. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(2), 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. (2019). Scale development and factor analysis. In Scholarly publishing and research methods across disciplines (pp. 159–183). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, G., & Lee, S. (2018). It doesn’t end there: Workplace bullying, work-to-family conflict, and employee well-being in Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7), 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J. H. (2020). Fuzzy moderation and moderated-mediation analysis. International Journal of Fuzzy Systems, 22(6), 1948–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabojnik, J. (2004). A model of rational bias in self-assessments. Economic Theory, 23(2), 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeike, S., Bradbury, K., Lindert, L., & Pfaff, H. (2019). Digital leadership skills and associations with psychological well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Variable Type | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate Culture | Independent variable | X |

| Psychological Well-being | Dependent variable | Y |

| Working Atmosphere | Mediator variable | M |

| Pathological Relationships | Moderation variable | W |

| Leadership | Moderation variable | Z |

| Levene’s Test of Equality of Error Variances | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: Psychological well-being | |||

| F | df1 | df2 | Sig. |

| 3.383 | 124 | 316 | 0.000 |

| Tests the null hypothesis that the error variance of the dependent variable is equal across groups. | |||

| Reliability Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Cronbach’s alpha | N of items |

| 0.935 | 5 |

| Outcome Variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Summary | ||||||

| R | R-sq | MSE | F (HC4) | df1 | df2 | p |

| 0.7075 | 0.5006 | 0.6753 | 352.6481 | 1.000 | 439.000 | 0.000 |

| Model | ||||||

| Coeff | SE (HC4) | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Constant | 0.4781 | 0.0881 | 5.4255 | 0.000 | 0.3049 | 0.6513 |

| Corporate Culture | 0.7046 | 0.0375 | 18.7789 | 0.000 | 0.6308 | 0.7783 |

| Outcome Variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Summary | ||||||

| R | R-sq | MSE | F (HC4) | df1 | df2 | p |

| 0.8981 | 0.8067 | 0.3161 | 459.1341 | 8.000 | 432.000 | 0.000 |

| Model | ||||||

| Coeff | SE (HC4) | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Constant | −0.2783 | 0.1339 | −2.0787 | 0.0382 | −0.5414 | −0.0152 |

| Corporate Culture | 0.0390 | 0.0925 | 0.4216 | 0.6735 | −0.1428 | 0.2208 |

| Working Atmosphere | 0.6355 | 0.1158 | 5.4870 | 0.0000 | 0.4079 | 0.8631 |

| Pathological Relationships | 0.4283 | 0.1746 | 2.4523 | 0.0146 | 0.0850 | 0.7715 |

| Interaction 1 | −0.0622 | 0.0581 | −1.0720 | 0.2843 | −0.1764 | 0.0519 |

| Interaction 2 | 0.0486 | 0.0563 | 0.8637 | 0.3882 | −0.0620 | 0.1592 |

| Leadership | 0.3725 | 0.1676 | 2.2227 | 0.0268 | 0.0431 | 0.7019 |

| Interaction 3 | 0.0787 | 0.0644 | 1.2206 | 0.2229 | −0.0480 | 0.2053 |

| Interaction 4 | −0.1459 | 0.0619 | −2.3574 | 0.0188 | −0.2675 | −0.0243 |

| Interaction 1: corporate culture and pathological relationships | ||||||

| Interaction 2: work atmosphere and pathological relationships | ||||||

| Interaction 3: corporate culture and leadership | ||||||

| Interaction 4: work atmosphere and leadership | ||||||

| Indices of Partial Moderated Mediation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

| Pathological relationships | 0.0342 | 0.0347 | −0.0344 | 0.1011 |

| Leadership | −0.1028 | 0.0359 | −0.1680 | −0.0253 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Michulek, J.; Gajanova, L.; Gajdosikova, D.; Senci, M. Corporate Culture, Leadership, and Pathological Relationships: A Moderated Mediation Model of Employees’ Well-Being. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15100399

Michulek J, Gajanova L, Gajdosikova D, Senci M. Corporate Culture, Leadership, and Pathological Relationships: A Moderated Mediation Model of Employees’ Well-Being. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(10):399. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15100399

Chicago/Turabian StyleMichulek, Jakub, Lubica Gajanova, Dominika Gajdosikova, and Matus Senci. 2025. "Corporate Culture, Leadership, and Pathological Relationships: A Moderated Mediation Model of Employees’ Well-Being" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 10: 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15100399

APA StyleMichulek, J., Gajanova, L., Gajdosikova, D., & Senci, M. (2025). Corporate Culture, Leadership, and Pathological Relationships: A Moderated Mediation Model of Employees’ Well-Being. Administrative Sciences, 15(10), 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15100399