Venture Capital as a Catalyst for Innovation and Economic Growth in Emerging Economies: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Venture Capital Concept

1.2. Venture Capital and High-Growth SMEs in Emerging Economies

1.3. Venture Capital and Barriers to Innovation

2. Method

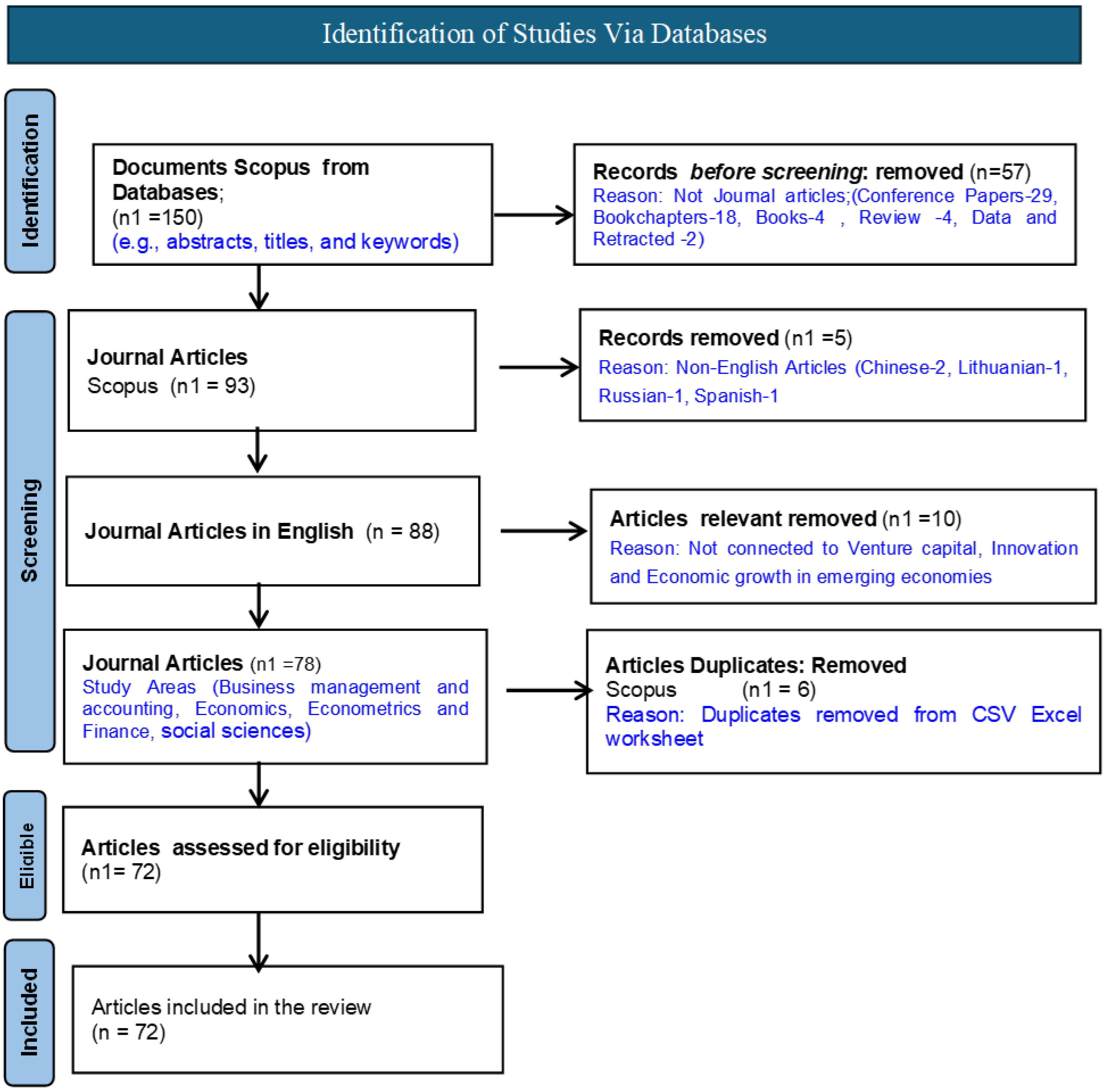

2.1. Study Identification and Sample

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Measures

3. Results

3.1. Systematic Review Scope and Coverage

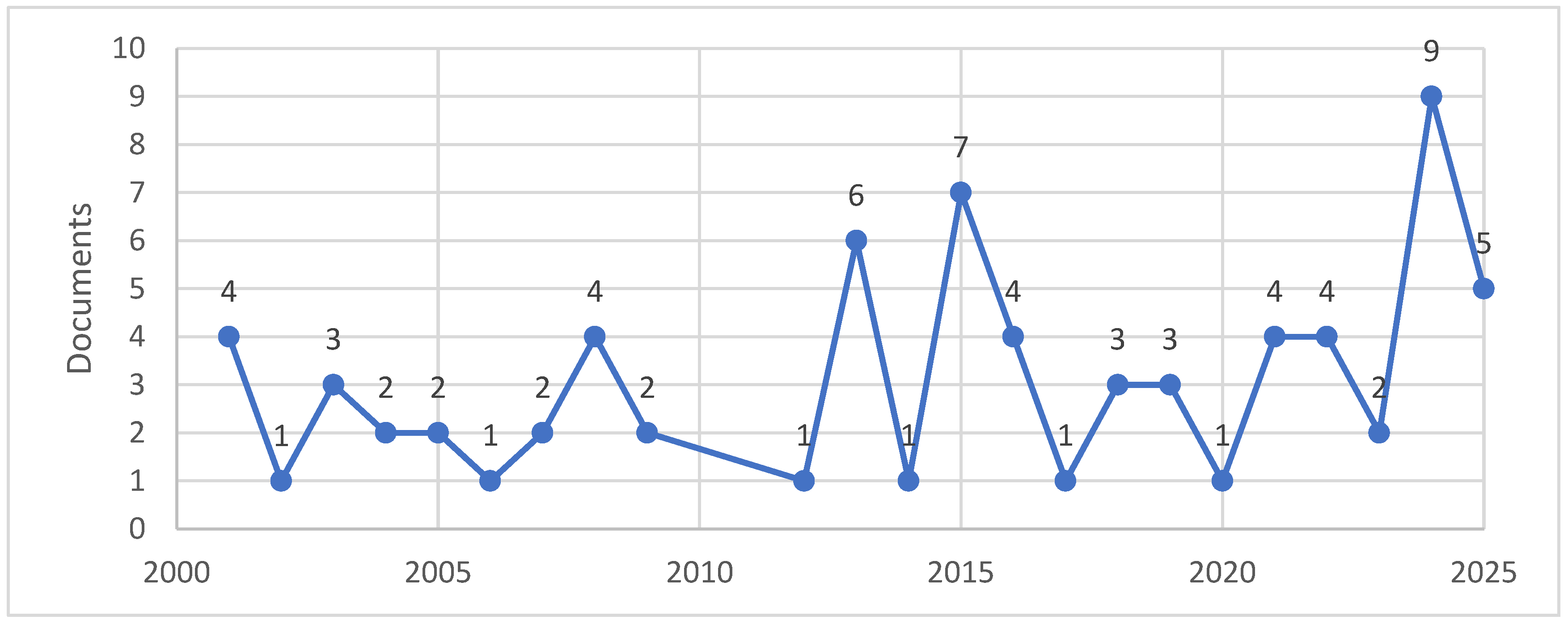

3.2. Overview of Article Publications by Year

3.3. Overview of Distribution of the Article by Journals

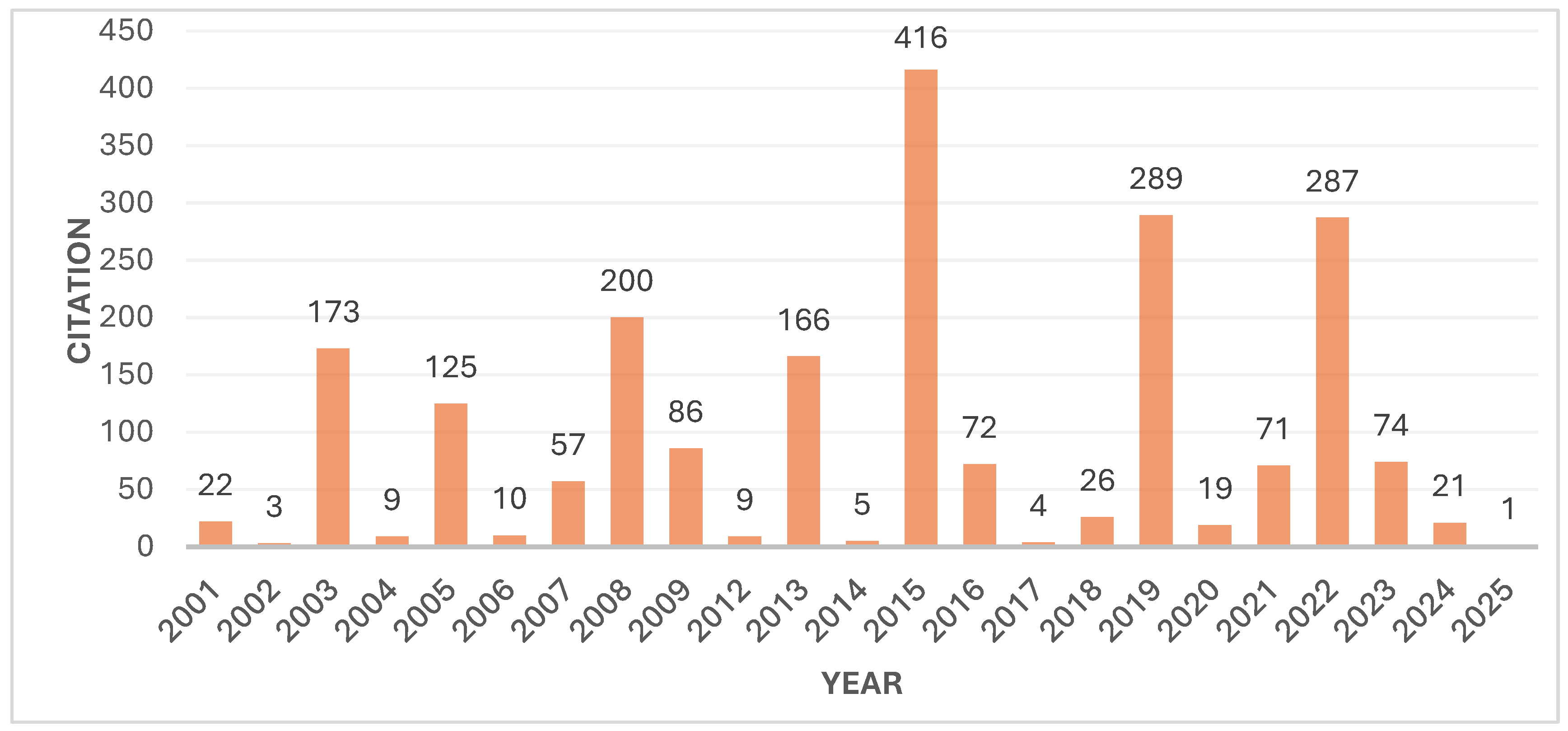

3.4. Analysis of Citation by Year

3.5. Distribution of Articles by Country

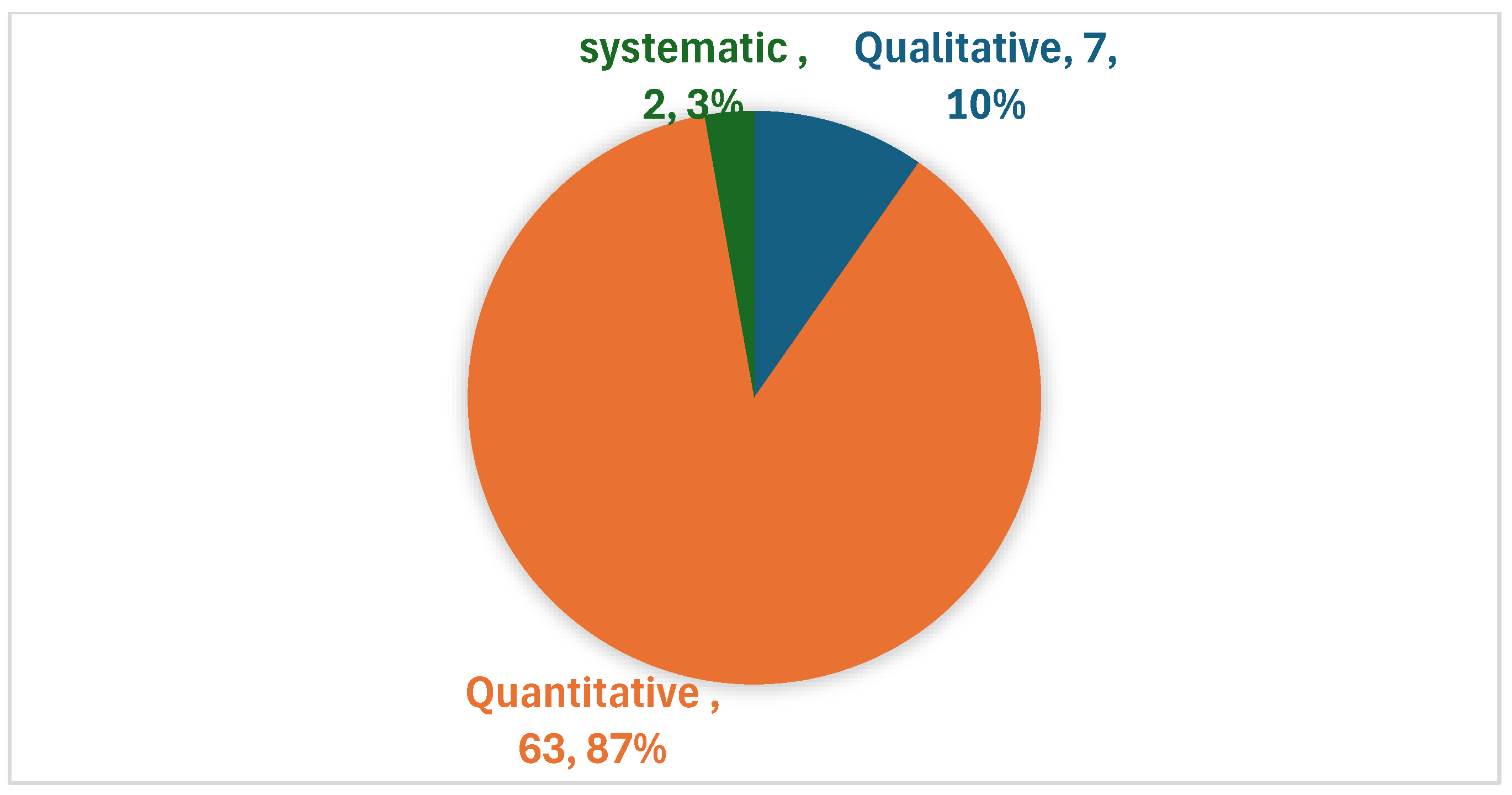

3.6. Analysis of Research Methods

4. Discussion

4.1. Venture Capital and Innovation in Emerging Economies

4.2. Venture Capital and Economic Growth of Emerging Economies

4.3. Venture Capital Growth in Emerging Economies

5. Conclusions

5.1. Contributions to Theory and Practice

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Avenues

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agstner, P. (2024). New legal forms and rules for Italian innovative enterprises. European Business Law Review, 35(7), 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrom, D., & Bruton, G. D. (2006). Venture capital in emerging economies: Networks and institutional change. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(2), 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alperovych, Y., Quas, A., & Standaert, T. (2018). Direct and indirect government venture capital investments in Europe. Economics Bulletin, 38(2), 1219–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassi, T. (2003). Innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 3(1–2), 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthurs, J. D., & Busenitz, L. W. (2003). The boundaries and limitations of agency theory and stewardship theory in the venture capitalist/entrepreneur relationship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(2), 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avnimelech, G., & Teubal, M. (2008). From direct support of business sector R&D/innovation to targeting venture capital/private equity: A catching-up innovation and technology policy life cycle perspective. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 17(1), 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldock, R. (2015). An assessment of the business impacts of the UK’s Enterprise Capital Funds. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 34(8), 1556–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa de Moraes, M., Lobosco, A., & Lima, E. (2013). Expectations of FINEP and São Paulo Anjos Agents concerning the use of venture capital in technology-based small and medium enterprises. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 8, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Bǎtrâncea, L. M. (2022). Determinants of economic growth across the European union: A panel data analysis on small and medium enterprises. Sustainability, 14(8), 4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M., & Hottenrott, H. (2021). Start-up subsidies and the sources of venture capital. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 16, e00272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, F., Colombo, M. G., & Grilli, L. (2011). Venture capital financing and the growth of high-tech start-ups: Disentangling treatment from selection effects. Research Policy, 40(7), 1028–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, F., Colombo, M. G., & Quas, A. (2019). The role of governmental venture capital in the venture capital ecosystem: An organizational ecology perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(3), 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J. H., Colombo, M. G., Cumming, D. J., & Vismara, S. (2018). New players in entrepreneurial finance and why they are there. Small Business Economics, 50(2), 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N. M. P. (2015). Sustainable venture capital—Catalyst for sustainable start-up success? Journal of Cleaner Production, 108, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowska, K. (2008). Business angels in Poland in comparison to the informal venture capital market in the European Union. Engineering Economics, 2(57), 7–14. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=952725 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Buah, E. K. (2017). Assessing the impact of venture capital financing on the growth of SMEs. Texila International Journal of Management, 3(2), 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellari, T., & Gucciardi, G. (2024). Equity investments and environmental pressure: The role of venture capital. Sustainability, 16(1), 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, S., Gatti, S., & Perrini, F. (2009). Are venture capitalists a catalyst for innovation? European Financial Management, 15, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattafi, G., Pistolesi, F., & Teti, E. (2025). Unlocking high-growth potential: Does intellectual capital efficiency drive European entrepreneurial ventures? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 32(1), 173–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieply, S. (2001). Bridging capital gaps to promote innovation in France. Industry and Innovation, 8(2), 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R., Cumming, D., & Li, D. (2016). Do banks or VCs spur small firm growth? Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 41, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M. G., D’Adda, D., & Pirelli, L. H. (2016). The participation of new technology-based firms in EU-funded R&D partnerships: The role of venture capital. Research Policy, 45(2), 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M. G., & Murtinu, S. (2017). Venture capital investments in Europe and portfolio firms’ economic performance: Independent versus corporate investors. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 26(1), 35–66. [Google Scholar]

- Corsi, C., & Prencipe, A. (2018). Foreign ownership and innovation in independent SMEs. A cross-European analysis. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 30(5), 397–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D., Deloof, M., Manigart, S., & Wright, M. (2019). New directions in entrepreneurial finance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 100, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D., Kumar, S., Lim, W. M., & Pandey, N. (2023). Mapping the venture capital and private equity research: A bibliometric review and future research agenda. Small Business Economics, 61(1), 173–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, P., & Danisman, G. O. (2019). Eco-innovation and firm growth in the circular economy: Evidence from European small- and medium-sized enterprises. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(8), 1608–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, P., & Parris, S. (2015). Access to finance for innovators in the UK’s environmental sector. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 27(7), 782–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q., Li, Z., Du, M., & Yang, T. (2024). Venture capital, innovation channels, and regional resource dependence: Evidence from China. Journal of Environmental Management, 352, 120034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldar, O., & Grennan, J. (2024). Common venture capital investors and startup growth. The Review of Financial Studies, 37(2), 549–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festel, G., Breitenmoser, P., Würmseher, M., & Kratzer, J. (2015). Early stage technology investments of pre-seed venture capitalists. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 7(4), 370–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, R., & Bendelá, F. (2024). The role of equity crowdfunding in the Brazilian entrepreneurial ecosystem: An empirical analysis. Administrative Sciences, 14(9), 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R., & Smith, D. F., Jr. (1990). Venture capital, innovation, and economic Development. Economic Development Quarterly, 4(4), 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freňáková, M., Kmeťová, O., & Blaščák, P. (2019). Features of venture capital funded enterprises: Evidence from Slovakia. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 17, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielsson, J., & Huse, M. (2005). Outside directors in SME boards: A call for theoretical reflections. Corporate Board: Role, Duties and Composition, 1(1), 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Godke Veiga, M., & McCahery, J. A. (2019). The financing of small and medium-sized enterprises: An analysis of the financing gap in Brazil. European Business Organisation Law Review, 20(4), 633–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompers, P. A. (1996). Grandstanding in the venture capital industry. Journal of Financial Economics, 42(1), 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyayeva, T. I., Kuznetsova, T. M., Gnezdova, J. v., Veselovsky, M. Y., & Avarskiy, N. D. (2016). Investing in innovation projects in Russia’s agrifood complex. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce, 21(6), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Haro de Rosario, A., del Carmen Caba-Pérez, M. C., & Cazorla-Papis, L. (2016). The impact of venture capital on investee companies: Evidence from Spain. Review of Managerial Science, 10(3), 577–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgersson, M. (2013). Patent management in entrepreneurial SMEs: A literature review and an empirical study of innovation appropriation, patent propensity, and motives. R and D Management, 43(1), 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X., Wang, Y., & Wang, M. (2016). The innovation and performance impacts of venture capital investment on China’s small- and medium-sized enterprises. China Economic Journal, 9(2), 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. T., & Khan, M. T. A. (2021). Factors influencing the adoption of crowdfunding in Bangladesh: A study of start-up entrepreneurs. Information Development, 37(1), 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarchow, S., & Röhm, A. (2023). Business builders, contractors, and entrepreneurs—An exploratory study of IP venturing funds. Journal of Small Business Management, 61(4), 1451–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaivanto, K., & Stoneman, P. (2007). Public provision of sales contingent claims backed finance to SMEs: A policy alternative. Research Policy, 36(5), 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M. Y. (2020). Sustainable profit versus unsustainable growth: Are venture capital investments and governmental support medicines or poisons? Sustainability, 12(18), 7773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimkhani, M., Pakizeh, K., & Akhavan Anvari, M. R. A. (2022). Identifying and prioritising factors affecting innovation of investee companies from the perspective of venture capitalists: A case study. Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 15(3), 633–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A. I. (2024). Building resilience and sustainability in small businesses enterprises through sustainable venture capital investment in sub-Saharan Africa. Cogent Economics & Finance, 12(1), 2399760. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, A. I. (2025). Unveiling venture capital’s disruptive power; fuelling innovation and economic growth in high-impact firms in East Africa. Future Business Journal, 11(1), 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A. I., & Chiloane-Tsoka, G. E. (2024). Transforming early-stage firms in emerging countries: Unveiling the power of venture capital; a comparative study of South Africa and Kenya. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2360502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A. I., & Tsoka, G. E. (2020). Impact of venture capital financing on small-and medium-sized enterprises’ performance in Uganda. The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 12(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, R., Harms, J., Liket, K., & Maas, K. (2017). Small firms, large impact? A systematic review of the SME finance literature. World Development, 97, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. I., & Hussain, J. G. (2024). Informal venture capital in emerging economies: A case of Pakistan. Venture Capital, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmakov, V. V., Polyakova, A. G., & Shalaev, V. S. (2015). An analysis of the impact of venture capital investment on economic growth and innovation: Evidence from the USA and Russia. Economic Annals, 60(207), 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. S., & Wang, J.-C. (2003). Public policies for the promotion of an innovation-driven economy in Taiwan. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 3(3), 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. (2010). The future of public efforts to boost entrepreneurship and venture capital. Small Business Economics, 35(3), 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J., & Nanda, R. (2020). Venture capital’s role in financing innovation: What we know and how much we still need to learn. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(3), 237–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, L., Tang, J., Karami, M., Busenitz, L., & Kacmar, K. M. (2022). Increasing alertness to new opportunities: The influence of positive affect and implications for innovation. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 39(1), 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingelbach, D. (2013). Paradise postponed? Venture capital emergence in Russia. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 9(1), 204–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q., & Shen, R. (2025). A tale of dual institutional logics: The impact of government venture capital involvement on SMEs’ green innovation performance. Venture Capital. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, E., Bender, M., Achleitner, A. K., & Kaserer, C. (2013). Importance of spatial proximity between venture capital investors and investees in Germany. Journal of Business Research, 66(11), 2346–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadea, D., & Pillay, M. K. (2008). Environmental conditions for SMME development in a South African province. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 11(4), 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangematin, V., Lemarié, S., Boissin, J.-P., Catherine, D., Corolleur, F., Coronini, R., & Trommetter, M. (2003). Development of SMEs and heterogeneity of trajectories: The case of biotechnology in France. Research Policy, 32(4), 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, B., Mohammadali-Haji, A., Botha, I., Madikizela, B., & Madiba, T. (2021). Special purpose acquisition companies as a vehicle for providing venture capital to small and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 14(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbhele, T. P. (2012). The study of venture capital finance and investment behaviour in small and medium-sized enterprises. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 15(1), 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, P., Cooper, S., & Van der Sijde, P. (2011). Entrepreneurship and high-technology ventures. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 17(6). [Google Scholar]

- Milton-Smith, J. (2001). The role of SMES in commercialising university research & development: The Asia-pacific experience. Small Business Economics, 16(2), 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, A., di Minin, A. D., Martelli, I., Testa, G., & Santoleri, P. (2021). Public funding of innovation: Exploring applications and allocations of the European SME Instrument. Research Policy, 50(1), 104131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawczyński, R. (2020). Venture capitalists’ investment criteria in Poland: Entrepreneurial opportunities, entrepreneurs, and founding teams. Administrative Sciences, 10(4), 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R., Botelho, T., Hussain, J., & Anwar, O. (2023). Solving the SME finance puzzle: An examination of demand and supply failure in the UK. Venture Capital, 25(1), 31–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmieri, E., & Ferilli, G. B. (2024). Innovating the bank-firm relationship: A spherical fuzzy approach to SME funding. European Journal of Innovation Management, 27(9), 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantea, S., & Tkacik, M. (2024). Venture capital and high-tech start-ups in Europe: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Venture Capital, 27, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R. P., Maradana, R. P., Dash, S., Zaki, D. B., Gaurav, K., & Jayakumar, M. (2017). Venture capital, innovation activities, and economic growth: Are feedback effects at work? Innovation, 19(2), 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaní, G. R., & Atienza-Ubeda, M. A. (2006). Venture capital in Latin America: Evolution and prospects in Chile. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 6(4–5), 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbusch, N., Brinckmann, J., & Müller, V. (2013). Does acquiring venture capital pay off for the funded firms? A meta-analysis on the relationship between venture capital investment and funded firm financial performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(3), 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S. P. S., Bonanno, G., Giansoldati, M., & Gregori, T. (2018). Are Venture Capital SMEs more likely to start exporting? Economics Bulletin, 38(3), 1613–1622. [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq, M., Nonthapot, S., Mohamad, S., Keong, O., Ehsanullah, S., & Iqbal, N. (2022). Does green finance matter for sustainable entrepreneurship and environmental corporate social responsibility during COVID-19? China Finance Review International, 12(2), 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samila, S., & Sorenson, O. (2011). Venture capital, entrepreneurship, and economic growth. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1), 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidei, V. V., Onishchenko, S., Zhydovska, N., Borodenko, T., & Abramova, M. (2025). The influence of fintech startups on the dynamics of innovative development of the financial market. Management:(Montevideo), 3, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipola, S. (2022). Another Silicon Valley? Tracking the role of entrepreneurship culture in start-up and venture capital co-evolution in Finland’s entrepreneurial ecosystem 1980–1997. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 14(3), 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, O., & Stuart, T. E. (2001). Syndication networks and the spatial distribution of venture capital investments. American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1546–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillan, J. E., & Ziemnowics, C. (2002). Advanced technology and entrepreneurship opportunities: Examples in Poland. Journal of East-West Business, 7(2), 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarić, M. Š. (2017). SMEs perspective on venture capital investment criteria-A study of Croatian SMEs. Management-Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 22(1), 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahai, A., & Meyer, M. J. (1999). A revealed preference study of management journals’ direct influences. Strategic Management Journal, 20(3), 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, J. A., & Bygrave, W. D. (1986). Venture capital’s role in financing innovation for economic growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 1(2), 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres de Oliveira, R., Gentile-Lüdecke, S., & Figueira, S. (2022). Barriers to innovation and innovation performance: The mediating role of external knowledge search in emerging economies. Small Business Economics, 58(4), 1953–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F. S., Hsieh, L. H., Fang, S. C., & Lin, J. L. (2009). The co-evolution of business incubation and national innovation systems in Taiwan. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 76(5), 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.-H., & Wang, J.-C. (2004). The innovation policy and performance of innovation in Taiwan’s technology-intensive industries. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, K.-H., & Wang, J.-C. (2005). An examination of Taiwan’s innovation policy measures and their effects. International Journal of Technology and Globalisation, 1(2), 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykvová, T. (2018). Venture capital and private equity financing: An overview of recent literature and an agenda for future research. Journal of Business Economics, 88, 325–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. (2023). The ownership structure of corporate venture capital financing and innovation. Technovation, 123, 102736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonglimpiyarat, J. (2007). Management and governance of venture capital: A challenge for commercial banks. Technovation, 27(12), 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, R., Wang, H., Lyu, B., & Xia, Q. (2023). Does venture capital help to promote open innovation practice? Evidence from China. European Journal of Innovation Management, 26(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H., Liu, J., & Zeng, N. (2024). How to promote the digital business model innovation of high-tech SMEs through government venture capital? An evolutionary game perspective. Managerial and Decision Economics, 45(5), 3193–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.-W., Stephens, A. R., & Zhang, W. (2024). Proactive market orientation towards export performance within SMEs: A comparative study between the US and South Korea. Asia Pacific Business Review, 1(23). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharakis, A. L., McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2007). Venture capitalists’ decision policies across three countries: An institutional theory perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(5), 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2025). The impact of government industrial funds on the innovation of SMEs in China. Journal of Asian Economics, 97, 101898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Journals | Citations |

|---|---|

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 295 |

| Research Policy | 276 |

| Business Strategy and the Environment | 246 |

| China Finance Review International | 191 |

| R and D Management | 129 |

| International Small Business Journal | 115 |

| Corporate Board: Role, Duties and Composition | 111 |

| Technological Forecasting and Social Change | 84 |

| Small Business Economics | 68 |

| European Journal of Innovation Management | 63 |

| Sustainability (Switzerland) | 59 |

| Economics of Innovation and New Technology | 55 |

| Technology Analysis and Strategic Management | 54 |

| European Business Organisation Law Review | 43 |

| International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management | 41 |

| Technovation | 34 |

| South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences | 28 |

| Journal of Entrepreneurship | 21 |

| Venture Capital | 21 |

| Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy | 20 |

| Journal of Technology Management and Innovation | 15 |

| International Journal of Technology and Globalisation | 14 |

| Journal of King Abdulaziz University, Islamic Economics | 14 |

| Social Sciences and Humanities Open | 13 |

| Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship | 12 |

| Central Asia and the Caucasus | 11 |

| China Economic Journal | 11 |

| Engineering Economics | 11 |

| European Research Studies Journal | 11 |

| Industry and Innovation | 11 |

| Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal | 7 |

| Cogent Business and Management | 6 |

| Critical Perspectives on International Business | 6 |

| Cogent Economics and Finance | 5 |

| Enterprise Development and Microfinance | 5 |

| Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce | 5 |

| Problems and Perspectives in Management | 5 |

| Review of Managerial Science | 5 |

| Management (Croatia) | 4 |

| Singapore Economic Review | 4 |

| Economics Bulletin | 3 |

| Journal of East-West Business | 3 |

| Asia Pacific Business Review | 2 |

| Comparative Economic Research | 2 |

| Journal of International Food and Agribusiness Marketing | 2 |

| Administrative Sciences | 1 |

| European Business Law Review | 1 |

| Journal of Asian Economics | 1 |

| Managerial and Decision Economics | 1 |

| Grand Total | 2145 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kato, A.I. Venture Capital as a Catalyst for Innovation and Economic Growth in Emerging Economies: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110405

Kato AI. Venture Capital as a Catalyst for Innovation and Economic Growth in Emerging Economies: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):405. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110405

Chicago/Turabian StyleKato, Ahmed I. 2025. "Venture Capital as a Catalyst for Innovation and Economic Growth in Emerging Economies: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110405

APA StyleKato, A. I. (2025). Venture Capital as a Catalyst for Innovation and Economic Growth in Emerging Economies: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110405