The Science of Organisational Resilience: Decoding Its Intellectual Structure to Understand Foundations and Future

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

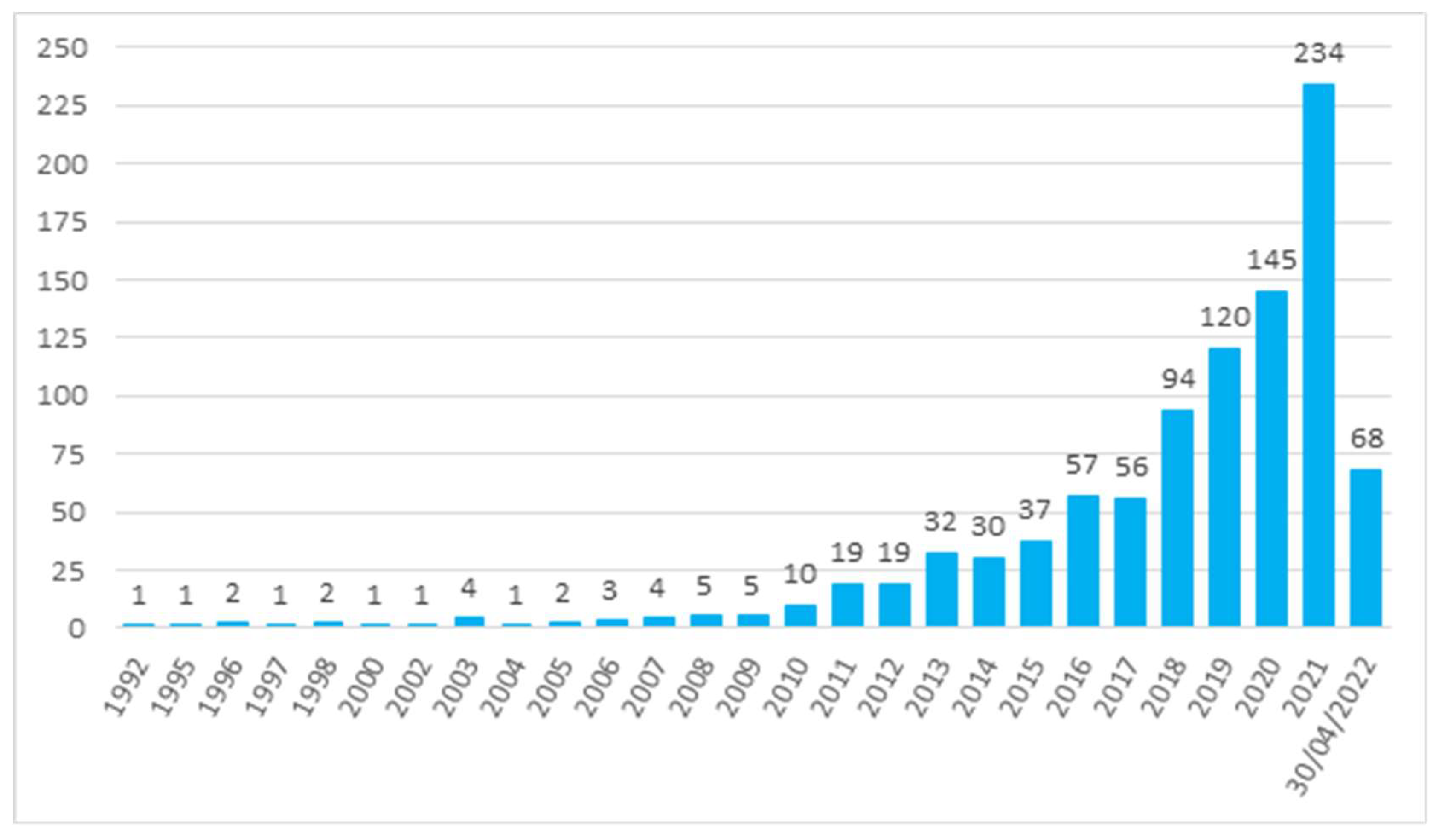

3. Results and Discussion

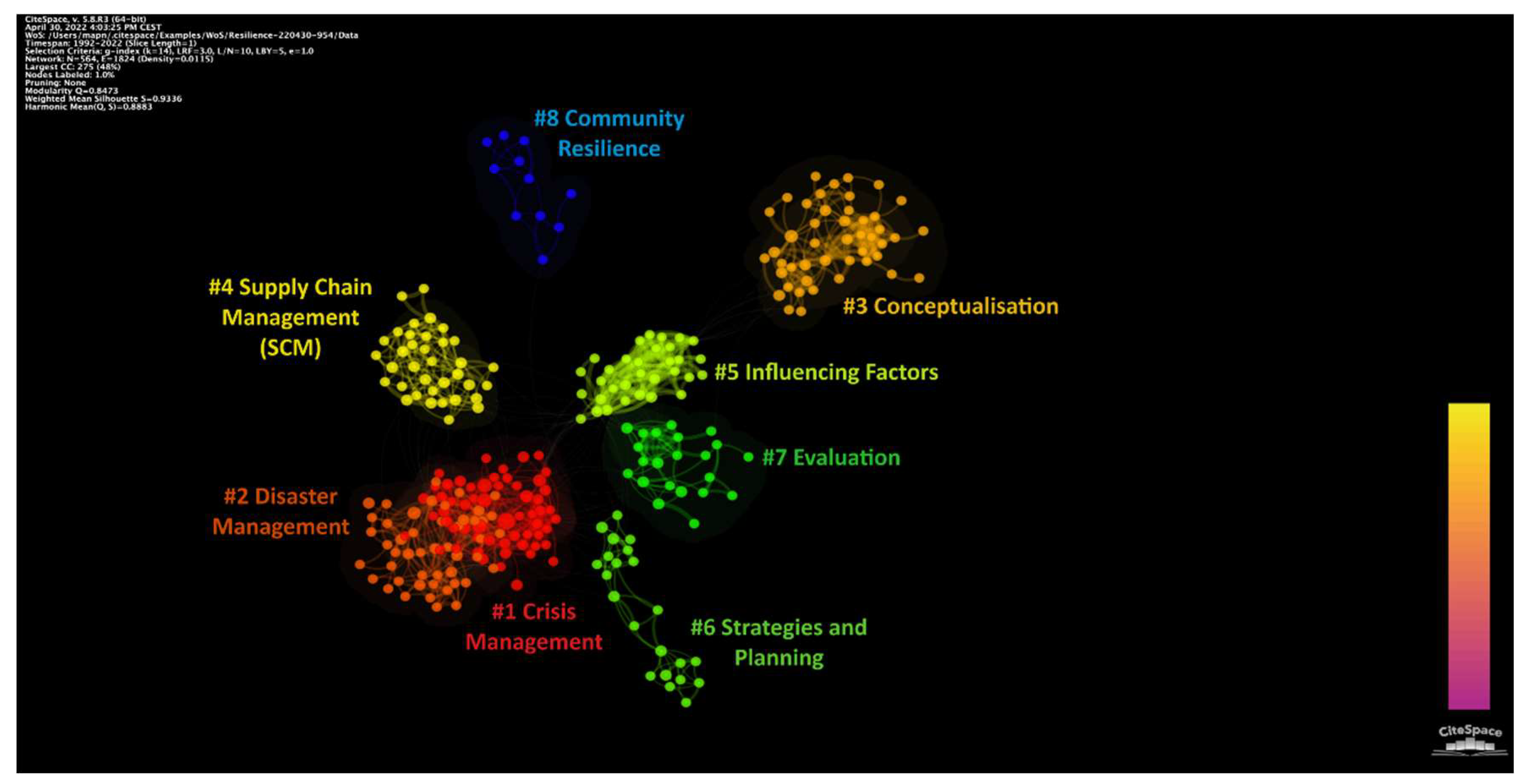

3.1. Main Areas of Research in OR

Synthesis and Inter-Cluster Relationships

3.2. Intellectual Turning Points in OR

3.3. Burst Detection in OR

4. Research Agenda

- RQ1: Under what conditions can organisations integrate digital operational resilience into their strategic planning to mitigate the societal impact of cyber crises?

- RQ2: Under what conditions do proactive crisis anticipation capabilities complement or conflict with reactive disaster recovery mechanisms, and how does this interaction vary across different types of disruptions and organisational contexts?

- RQ3: How do organisations develop “temporal resilience,” the capacity to simultaneously maintain early warning systems and preserve reactive recovery capabilities without resource cannibalisation?

- RQ4: How can organisations resolve the inherent tension between resilience redundancies and sustainability efficiency, and what dynamic capabilities enable the co-evolution of both objectives?

- RQ5: What role do “soft” influence factors play in mediating the paradox between resilience and sustainability?

- RQ6: How does OR influence legitimisation processes with diverse stakeholders during prolonged crises, particularly in highly visible social contexts, such as sports organisations?

- RQ7: What resilience practices enable organisations to maintain or enhance their legitimacy when operating simultaneously in multiple institutional contexts?

- RQ8: How can AI-driven predictive models improve early warning systems while maintaining ethical standards, organisational legitimacy, and human agency in crisis decision-making?

- RQ9: What governance frameworks can balance the efficiency gains of automated resilience systems with the ethical imperatives of transparency, accountability, and stakeholder inclusion?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer on the Use of Generative AI Tools:

References

- Abdullahi, U., Mohamed, A. M., & Senasi, V. (2023). Exploring global trends of research on organizational resilience and sustainability: A bibliometric review. Journal of International Studies (Malaysia), 19(2), 27–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W. N. (2000). Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Progress in Human Geography, 24(3), 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, H., & Özer-Çaylan, D. (2022). Achieving organizational resilience through complex adaptive systems approach: A conceptual framework. Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 20(4), 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksić, A., Stefanović, M., Arsovski, S., & Tadić, D. (2013). An assessment of organizational resilience potential in smes of the process industry, a fuzzy approach. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries, 26(6), 1238–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambulkar, S., Blackhurst, J., & Grawe, S. (2015). Firm’s resilience to supply chain disruptions: Scale development and empirical examination. Journal of Operations Management, 33–34(1), 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarelli, A., & Nonino, F. (2016). Strategic and operational management of organizational resilience: Current state of research and future directions. Omega-International Journal of Management Science, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C. (1993). Knowledge for action: A guide to overcoming barriers to organizational change. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Aven, T. (2016). Risk assessment and risk management: Review of recent advances on their foundation. European Journal of Operational Research, 253(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, R. (2018). An introduction to bibliometrics: New developments and trends. Chandos Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Barasa, E., Mbau, R., & Gilson, L. (2018). What is resilience and how can it be nurtured? A systematic review of empirical literature on organizational resilience. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 7(6), 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, M., & Deakins, D. (2017). The relationship between dynamic capabilities, the firm’s resource base and performance in a post-disaster environment. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 35(1), 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F., & Ross, H. (2013). Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Society & Natural Resources, 26(1), 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamra, R., Dani, S., & Burnard, K. (2011). Resilience: The concept, a literature review and future directions. International Journal of Production Research, 49(18), 5375–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A., & Van Eeten, M. J. G. (2013). The resilient organization. Public Management Review, 15(3), 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronzo, M., Barbosa, M. W., de Sousa, P. R., Torres Junior, N., & Valadares de Oliveira, M. P. (2024). Leveraging supply chain reaction time: The effects of big data analytics capabilities on organizational resilience enhancement in the auto-parts industry. Administrative Sciences, 14(8), 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N. A., Orchiston, C., Rovins, J. E., Feldmann-Jensen, S., & Johnston, D. (2018). An integrative framework for investigating disaster resilience within the hotel sector. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 36, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N. A., Rovins, J. E., Feldmann-Jensen, S., Orchiston, C., & Johnston, D. (2017). Exploring disaster resilience within the hotel sector: A systematic review of literature. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 22, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno Campos, E., Murcia Rivera, C., & Merino Moreno, C. (2019). Resilient organizational capabilities in NTBFs. Concept and variables as dynamic and adaptive capabilities. Small Business International Review, 3(2), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnard, K., & Bhamra, R. (2011). Organisational resilience: Development of a conceptual framework for organisational responses. International Journal of Production Research, 49(18), 5581–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bygrave, L. A. (2025). The emergence of EU cybersecurity law: A tale of lemons, angst, turf, surf and grey boxes. Computer Law & Security Review, 56, 106071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A., Figueiredo, J., Oliveira, I., & Pocinho, M. (2025). From crisis to opportunity: Digital transformation, digital business models, and organizational resilience in the post-pandemic era. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. (2017). Science mapping: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Data and Information Science, 2(2), 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Chen, Y., Horowitz, M., Hou, H., Liu, Z., & Pellegrino, D. (2009). Towards an explanatory and computational theory of scientific discovery. Journal of Informetrics, 3(3), 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Ibekwe-SanJuan, F., & Hou, J. (2010). The structure and dynamics of cocitation clusters: A multiple-perspective cocitation analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(7), 1386–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., & Song, M. (2019). Visualizing a field of research: A methodology of systematic scientometric reviews. PLoS ONE, 14(10), e0223994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chewning, L. V., Lai, C.-H., & Doerfel, M. L. (2013). Organizational resilience and using information and communication technologies to rebuild communication structures. Management Communication Quarterly, 27(2), 237–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chonsawat, N., & Sopadang, A. (2020). Defining SMEs’ 4.0 readiness indicators. Applied Sciences, 10(24), 8998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M. M. H., & Quaddus, M. (2017). Supply chain resilience: Conceptualization and scale development using dynamic capability theory. International Journal of Production Economics, 188, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales-Estrada, A. M., Gomez-Santos, L. L., Bernal-Torres, C. A., & Rodriguez-Lopez, J. E. (2021). Sustainability and resilience organizational capabilities to enhance business continuity management: A literature review. Sustainability, 13(15), 8196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N. K., & Roy, A. (2022). COVID-19 and agri-food value chain: A systematic review and bibliometric mapping. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 12(3), 442–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Martín, F., Blanco-González, A., & Prado-Román, C. (2020). The intellectual structure of organizational legitimacy research: A co-citation analysis in business journals. Review of Managerial Science, 15(4), 1007–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Martín, F., Miotto, G., & Del-Castillo-Feito, C. (2024). The intellectual structure of gender equality research in the business economics literature. Review of Managerial Science, 18, 1649–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M. (2020). The entrepreneurship power house of ambition and innovation: Exploring German wineries. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 41(3), 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchek, S. (2020). Organizational resilience: A capability-based conceptualization. Business Research, 13(1), 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egghe, L. (2006). Theory and practise of the g-index. Scientometrics, 69(1), 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, O., Henry, D., Sauser, B., & Mansouri, M. (2010, April 5–8). Perspectives on measuring enterprise resilience. 2010 IEEE International Systems Conference (pp. 587–592), San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. (2019). Regulation (EU) 2019/881 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on ENISA (the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity) and on information and communications technology cybersecurity certification and repealing Regulation (EU) No 526/2013 (Cybersecurity Act) (Text with EEA relevance). Official Journal of the European Union, L 151(7.6.2019), 15–69, Document 32019R0881. PE/86/2018/REV/1. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/881/oj# (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- European Union. (2022). Regulation (EU) 2022/2554 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on digital operational resilience for the financial sector and amending Regulations (EC) No 1060/2009, (EU) No 648/2012, (EU) No 600/2014, (EU) No 909/2014 and (EU) 2016/1011 (Text with EEA relevance). Official Journal of the European Union, L 333(27.12.2022), 1–79, Document 32022R2554. PE/41/2022/INIT. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2022/2554/oj/eng (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Fahimnia, B., & Jabbarzadeh, A. (2016). Marrying supply chain sustainability and resilience: A match made in heaven. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 91, 306–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. (2006). Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, M. F. d., & Ribas Filho, D. (2021). Facing the BANI world. International Journal of Nutrology, 14(2), e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, R. R. (2014). Resilience as effective functional capacity: An ecological-stress model. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 24(8), 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A., Rai, B. K., & Griffin, M. (2011). Resilience and Competitiveness of small and medium size enterprises: An empirical research. International Journal of Production Research, 49(18), 5489–5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedner, T., Abouzeedan, A., & Klofsten, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial resilience. Annals of Innovation & Entrepreneurship, 2(1), 7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbane, B. (2019). Rethinking organizational resilience and strategic renewal in SMEs. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 31(5–6), 476–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, J. (2021). Disciplines of organizational resilience: Contributions, critiques, and future research avenues. Review of Managerial Science, 15(4), 879–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenstein, N.-O., Feisel, E., Hartmann, E., & Giunipero, L. (2015). Research on the phenomenon of supply chain resilience: A systematic review and paths for further investigation. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 45(1/2), 90–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S., Barker, K., & Ramirez-Marquez, J. E. (2016). A review of definitions and measures of system resilience. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 145, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S., Ivanov, D., & Dolgui, A. (2019). Review of quantitative methods for supply chain resilience analysis. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 125, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T., Edgeman, R., & Alnajem, M. N. (2023). Exploring the intellectual structure of research in organizational resilience through a bibliometric approach. Sustainability, 15(17), 12980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. (2018). Revealing interfaces of supply chain resilience and sustainability: A simulation study. International Journal of Production Research, 56(10), 3507–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbarzadeh, A., Fahimnia, B., & Sabouhi, F. (2018). Resilient and sustainable supply chain design: Sustainability analysis under disruption risks. International Journal of Production Research, 56(17), 5945–5968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Ritchie, B. W., & Verreynne, M. (2019). Building tourism organizational resilience to crises and disasters: A dynamic capabilities view. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(6), 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N., Elliott, D., & Drake, P. (2013). Exploring the role of social capital in facilitating supply chain resilience. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 18(3), 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan-Vallverdú, V., Plaza-Navas, M.-A., Maria Raya, J., & Torres-Pruñonosa, J. (2024). The Intellectual Structure of Esports Research. Entertainment Computing, 49, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalahmadi, M., & Parast, M. M. (2016). A review of the literature on the principles of enterprise and supply chain resilience: Major findings and directions for future research. International Journal of Production Economics, 171 Pt 1, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khin Khin Oo, N. C., & Rakthin, S. (2022). Integrative review of absorptive capacity’s role in fostering organizational resilience and research agenda. Sustainability, 14(19), 12570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinberg, J. (2003). Bursty and hierarchical structure in streams. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 7(4), 373–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S. N., Ganesh, L. S., & Rajendran, C. (2022). Entrepreneurial interventions for crisis management: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on entrepreneurial ventures. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 72, 102830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamhour, O., Safaa, L., & Perkumiene, D. (2023). What does the concept of resilience in tourism mean in the time of COVID-19? Results of a bibliometric analysis. Sustainability, 15(12), 9797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. V., Vargo, J., & Seville, E. (2013). Developing a tool to measure and compare organizations’ resilience. Natural Hazards Review, 14(1), 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C. A., Beck, T. E., & Lengnick-Hall, M. L. (2011). Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 21(3), 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkov, I., Fox-Lent, C., Read, L., Allen, C. R., Arnott, J. C., Bellini, E., Coaffee, J., Florin, M., Hatfield, K., Hyde, I., Hynes, W., Jovanovic, A., Kasperson, R., Katzenberger, J., Keys, P. W., Lambert, J. H., Moss, R., Murdoch, P. S., Palma-Oliveira, J., … Woods, D. (2018). Tiered approach to resilience assessment. Risk Analysis, 38(9), 1772–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linnenluecke, M. K. (2017). Resilience in business and management research: A review of influential publications and a research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(1), 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, D., Plaza-Navas, M. A., Torres-Pruñonosa, J., & Martinez, L. F. (2025). Navigating the landscape of e-commerce: Thematic clusters, intellectual turning points, and burst patterns in online reputation management. Electronic Commerce Research, 25(1), 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, Y. Y. G., Pérez-Martínez, N. G., García, V. H. B., & Martínez, F. de M. G. (2022). Organizational resilience: 30 years of intellectual structure and future perspectives [Resiliencia organizacional: 30 años de estructura intelectual y perspectivas a futuro]. Iberoamerican Journal of Science Measurement and Communication, 2(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytras, M. D., Serban, A. C., & Ntanos, S. (2025). Exploring distance learning in higher education: Satisfaction and insights from Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Romania, Turkey. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 26(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D., & Derickson, K. D. (2013). From resilience to resourcefulness: A critique of resilience policy and activism. Progress in Human Geography, 37(2), 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafimisebi, O. P., Ogunsade, A. I., Kehinde, W. O., Obembe, D., & Hadleigh-Dunn, S. (2025). Master of uncertainty: How strategic resilient organizations navigate crisis. Strategic Change. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamouni Limnios, E. A., Mazzarol, T., Ghadouani, A., & Schilizzi, S. G. M. (2014). The resilience architecture framework: Four organizational archetypes. European Management Journal, 32(1), 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-Tejón, J., Jiménez-Partearroyo, M., & Benito-Osorio, D. (2022). Security as a key contributor to organisational resilience: A bibliometric analysis of enterprise security risk management. Security Journal, 35(2), 600–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Martín, A., Orduna-Malea, E., Thelwall, M., & López-Cózar, E. D. (2018). Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. Journal of Informetrics, 12(4), 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S., Newell, J. P., & Stults, M. (2016). Defining urban resilience: A review. Landscape and Urban Planning, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M., Pancholi, G., & Saxena, A. (2024). Organizational resilience and sustainability: A bibliometric analysis. Cogent Business and Management, 11(1), 2294513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghel, I., Salanova Soria, M., & Martínez Martínez, I. M. (2013). El camino de la Resiliencia Organizacional: Una revisión teórica [The path of organizational resilience: A theoretical review]. Aloma: Revista de psicologia, ciències de l’educació i de l’esport, 31(2), 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Moral-Muñoz, J. A., Herrera-Viedma, E., Santisteban-Espejo, A., & Cobo, M. J. (2020). Software tools for conducting bibliometric analysis in science: An up-to-date review. El Profesional de la Información, 29(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, D. d., & Tomei, P. A. (2021). Strategic Management of Organizational Resilience (SMOR): A framework proposition. Revista Brasileira de Gestao de Negocios, 23(3), 536–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, S., Rajavel, S., Aggarwal, A. K., & Singh, A. (2020). Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity (VUCA) in context of the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and way forward. International Journal of Health Systems and Implementation Research, 4(2), 10–16. Available online: https://ijhsir.ahsas-pgichd.org/index.php/ijhsir/article/view/93.

- Orchiston, C., Prayag, G., & Brown, C. (2016). Organizational resilience in the tourism sector. Annals of Tourism Research, 56, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N., & Bansal, P. (2016). The long-term benefits of organizational resilience through sustainable business practices. Strategic Management Journal, 37(8), 1615–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otola, I., & Knop, L. (2023). A bibliometric analysis of resilience and business model usign VOSviewer. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 28(2), 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paeffgen, T. (2023). Organisational resilience during COVID-19 times: A bibliometric literature review. Sustainability, 15(1), 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R., Torstensson, H., & Mattila, H. (2014). Antecedents of organizational resilience in economic crises—An empirical study of swedish textile and clothing SMEs. International Journal of Production Economics, 147 Pt B, 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Martínez, N. G., Vega Esparza, R. M., & López López, Y. Y. G. (2022). Análisis de la resiliencia organizacional en tiempos de la COVID-19: Una mirada bibliométrica [Analysis of organizational resilience in times of COVID-19: A bibliometric overview]. Iberoamerican Journal of Science Measurement and Communication, 2(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, T. J., Croxton, K. L., & Fiksel, J. (2019). The evolution of resilience in supply chain management: A retrospective on ensuring supply chain resilience. Journal of Business Logistics, 40(1), 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarov, S. Y., & Holcomb, M. C. (2009). Understanding the concept of supply chain resilience. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 20(1), 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powley, E. H. (2009). Reclaiming resilience and safety: Resilience activation in the critical period of crisis. Human Relations, 62(9), 1289–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. (2021). Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications, 9(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radanliev, P., De Roure, D., Nicolescu, R., Huth, M., & Santos, O. (2022). Digital twins: Artificial intelligence and the IoT cyber-physical systems in Industry 4.0. International Journal of Intelligent Robotics and Applications, 6(1), 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, D. (2000). Building resilient organisations. OD Practitioner, 32(3), 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseeuw, P. J. (1987). Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M. (2020). How to survive COVID-19? Notes from organisational resilience [¿ Cómo sobrevivir al COVID-19? Apuntes desde la resiliencia organizacional]. International Journal of Social Psychology: Revista de Psicología Social, 35(3), 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchís Gisbert, R., & Poler Escoto, R. (2014). La resiliencia empresarial como ventaja competitiva [Business resilience as a competitive advantage]. II Congreso I+D+i Campus de Alcoi. Creando Sinergias. Libro de resúmenes, 25–28. Available online: https://riunet.upv.es/server/api/core/bitstreams/eb7efb31-829b-4a64-ba27-3ae085c26b90/content (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Schepers, J., Vandekerkhof, P., & Dillen, Y. (2021). The Impact of the COVID-19 crisis on growth-oriented SMEs: Building entrepreneurial resilience. Sustainability, 13(16), 9296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, K., Sharkey Scott, P., & Fynes, B. (2014). Mitigation processes—Antecedents for building supply chain resilience. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 19(2), 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffi, Y., & Rice, J. B., Jr. (2005). A supply chain view of the resilient enterprise. MIT Sloan Management Review, 47(1), 41–48. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/a-supply-chain-view-of-the-resilient-enterprise/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Shibata, N., Kajikawa, Y., & Matsushima, K. (2007). Topological analysis of citation networks to discover the future core articles. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(6), 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Santos, J. L., & Mueller, A. (2022). Resilience in the management and business research field: A bibliometric analysis. Management Letters/Cuadernos de Gestión, 22(2), 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H. (1973). Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 24(4), 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, S. (2009). Measuring resilience potential: An adaptive strategy for organizational crisis planning. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 17(1), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaans, M., & Waterhout, B. (2017). Building up resilience in cities worldwide: Rotterdam as participant in the 100 Resilient Cities Programme. Cities, 61, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoletti, P., & Za, S. (2021). Digital resilience to normal accidents in high-reliability organizations. In S. Aier, P. Rohner, & J. Schelp (Eds.), Engineering the transformation of the enterprise: A design science research perspective (pp. 339–353). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, K. M., & Vogus, T. J. (2003). Organizing for resilience. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 94–110, 390–392). Berrett-Koehler. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, E. D. O., & Werther, W. B. (2013). Resilience: Continuous renewal of competitive advantages. Business Horizons, 56(3), 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Pruñonosa, J., Plaza-Navas, M. A., Díez-Martín, F., & Beltran-Cangrós, A. (2021). The Intellectual Structure of Social and Sustainable Public Procurement Research: A Co-Citation Analysis. Sustainability, 13(2), 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, C. M., & Long, T. M. (2018). Document co-citation analysis to enhance transdisciplinary research. Science Advances, 4(1), e1701130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbano-Carazo, M. I. (2022). Factores Determinantes de la Gestion de Conocimiento y su incidencia en el Desempeño Organizacional en entornos BANI: Una revisión teórica [Determinant factors of knowledge management and their impact on organizational performance in BANI environments: A theoretical review]. Revista Científica Anfibios, 5(1), 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vegt, G. S., Essens, P., Wahlström, M., & George, G. (2015). Managing risk and resilience. Academy of Management Journal, 58(4), 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, J., & Seville, E. (2011). Crisis strategic planning for SMEs: Finding the silver lining. International Journal of Production Research, 49(18), 5619–5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viguri Axpe, M. R. (2024). Complejidad, Inteligencia Artificial y Ética [Complexity, artificial intelligence and ethics]. Revista Iberoamericana de Complejidad y Ciencias Económicas, 2(2), 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, J. A. (2005). Bibliometric methods: Pitfalls and possibilities. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology, 97(5), 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichselgartner, J., & Kelman, I. (2015). Geographies of resilience: Challenges and opportunities of a descriptive concept. Progress in Human Geography, 39(3), 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. A., Gruber, D. A., Sutcliffe, K. M., Shepherd, D. A., & Zhao, E. Y. (2017). Organizational response to adversity: Fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Academy of Management Annals, 11(2), 733–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. A., & Shepherd, D. A. (2016). Building resilience or providing sustenance: Different paths of emergent ventures in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake. Academy of Management Journal, 59(6), 2069–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, D. D. (2015). Four concepts for resilience and the implications for the future of resilience engineering. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 141, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., Hu, M., & Ji, Q. (2020). Financial markets under the global pandemic of COVID-19. Finance Research Letters, 36, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D., & Strotmann, A. (2015). Analysis and visualization of citation networks. Morgan & Claypool. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I., & Cater, T. (2015). Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organizational Research Methods, 18(3), 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Main Study Objectives | Research Method | Analysis Research Areas | Intellectual Turning Points | Burst Detection | Paper Co-Citation Analysis | Research Agenda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silva-Santos and Mueller (2022) | Identify, organise and integrate resilience knowledge in business management, focusing on challenges such as COVID-19 and examining its role in organisational adaptation and recovery from disruptions. | Bibliometric analysis, using co-citation counts, historiography, bibliometric coupling and cartography. | No | Partial (Descriptive analysis identifying most cited papers but lacks in-depth turning point analysis) | No | Partial (descriptive co-citation counts) | Yes |

| Khin Khin Oo and Rakthin (2022) | Explore the role of absorptive capacity in enhancing OR | Author co-citation bibliometric analysis and scoping review | Yes | No | No | No (only author co-citation analysis) | No |

| Hussain et al. (2023) | Analyse the evolution, trends, publication patterns and key subthemes of OR, while mapping the contributions of regions, countries, institutions and leading authors. | Authors co-citation analysis, co-citations counts and bibliographing coupling. | Yes | No | No | No (only author co-citation analysis) | No |

| Annarelli and Nonino (2016) | Investigate the resilience literature focusing on the strategic and operational management of OR. | Systematic literature and co-citation analysis based on multi-dimensional scaling and factor analysis. | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Moura and Tomei (2021) | Propose a framework for managing OR, particularly in response to crises such as COVID-19. | Literature review | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| This study | Aims to map the intellectual structure of OR by identifying key research clusters, influential works and emerging trends, while proposing future research directions to address literature gaps and to highlight areas for further exploration. | Paper bibliometric co-citation analysis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Parameters | Description | Selection |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Timeline | Analysed period | From 1992 to 2022 (30 April 2022) |

| (2) Source of terms | Processed text fields | Title/abstract/author key-words/keywords plus (all) |

| (3) Type of node | Type of network selected for analysis | Cited reference (the networks are made up of co-cited references) |

| (4) Pruning | It is systematically processed to remove excessive connections | None |

| (5) Selection of criteria | How to sample reports to form final networks | g-index (k = 14) |

| Cluster | Size | Silhouette | Year | Label | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 | 0.945 | 2016 | Crisis management | Exploring how resilient organisations cope effectively with a crisis |

| 2 | 48 | 0.876 | 2018 | Disaster management | Integrated approach for effective disaster resilience |

| 3 | 46 | 0.929 | 2009 | Conceptualisation | Development of OR concept |

| 4 | 36 | 0.922 | 2018 | SCM | The focus is on aspects related to organisational and supply chain resilience |

| 5 | 32 | 0.954 | 2013 | Influencing factors | Identifying factors that contribute to OR |

| 6 | 22 | 0.972 | 2015 | Strategy and planning | Strategy and planning actions to build effective OR |

| 7 | 22 | 0.963 | 2013 | Evaluation | Assessment of the level of resilience in organisations |

| 8 | 11 | 0.99 | 2014 | Community Resilience | They seek to explore and integrate resilience approaches to adapt them to communities |

| Cluster a | References | Strength b | Begin c | End d | 2009–2022 e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Somers (2009) | 4.4 | 2011 | 2013 |  |

| 3 | Lengnick-Hall et al. (2011) | 10.38 | 2013 | 2016 |  |

| 3 | Burnard and Bhamra (2011) | 5.7 | 2014 | 2016 |  |

| 3 | Bhamra et al. (2011) | 4.56 | 2014 | 2016 |  |

| 7 | Lee et al. (2013) | 6.97 | 2015 | 2018 |  |

| 1 | Pal et al. (2014) | 7.42 | 2016 | 2019 |  |

| 1 | Mamouni Limnios et al. (2014) | 5.32 | 2016 | 2018 |  |

| 1 | Boin and Van Eeten (2013) | 4.35 | 2016 | 2018 |  |

| 5 | Scholten et al. (2014) | 4.05 | 2016 | 2017 |  |

| 5 | Johnson et al. (2013) | 3.47 | 2016 | 2017 |  |

| 5 | Hohenstein et al. (2015) | 4.55 | 2017 | 2019 |  |

| 1 | Van der Vegt et al. (2015) | 8.88 | 2018 | 2020 |  |

| 1 | Ortiz-de-Mandojana and Bansal (2016) | 7.29 | 2019 | 2022 |  |

| 6 | Meerow et al. (2016) | 5.27 | 2019 | 2020 |  |

| 1 | Linnenluecke (2017) | 4.12 | 2019 | 2022 |  |

| 1 | Williams and Shepherd (2016) | 3.82 | 2019 | 2020 |  |

| 6 | Hosseini et al. (2016) | 3.49 | 2019 | 2022 |  |

| 1 | Williams et al. (2017) | 7.93 | 2020 | 2022 |  |

| 1 | Duchek (2020) | 6.64 | 2020 | 2022 |  |

| 2 | Barasa et al. (2018) | 4.4 | 2020 | 2022 |  |

| Cluster | Cluster label | Number of Papers a | Min (Year) b | Max (Year) c | Mean (Year) d | Mean (Strength) e | Min (Begin) f | Max (End) g | 2009–2022 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Conceptualisation | 4 | 2009 | 2011 | 2011 | 6.26 | 2011 | 2016 |  |

| 5 | Influencing Factors | 3 | 2013 | 2015 | 2014 | 4.02 | 2016 | 2019 |  |

| 1 | Crisis Management | 9 | 2013 | 2020 | 2016 | 6.20 | 2016 | 2022 |  |

| 6 | Strategy and planning | 2 | 2016 | 2016 | 2016 | 4.38 | 2019 | 2022 |  |

| 2 | Disaster management | 1 | 2018 | 2018 | 2018 | 4.40 | 2020 | 2022 |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toro-Gallego, C.; Sapena-Bolufer, J.; Plaza-Navas, M.-A.; Torres-Pruñonosa, J. The Science of Organisational Resilience: Decoding Its Intellectual Structure to Understand Foundations and Future. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15100404

Toro-Gallego C, Sapena-Bolufer J, Plaza-Navas M-A, Torres-Pruñonosa J. The Science of Organisational Resilience: Decoding Its Intellectual Structure to Understand Foundations and Future. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(10):404. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15100404

Chicago/Turabian StyleToro-Gallego, Cristóbal, Juan Sapena-Bolufer, Miquel-Angel Plaza-Navas, and Jose Torres-Pruñonosa. 2025. "The Science of Organisational Resilience: Decoding Its Intellectual Structure to Understand Foundations and Future" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 10: 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15100404

APA StyleToro-Gallego, C., Sapena-Bolufer, J., Plaza-Navas, M.-A., & Torres-Pruñonosa, J. (2025). The Science of Organisational Resilience: Decoding Its Intellectual Structure to Understand Foundations and Future. Administrative Sciences, 15(10), 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15100404