The Entrepreneurial Impact of the European Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

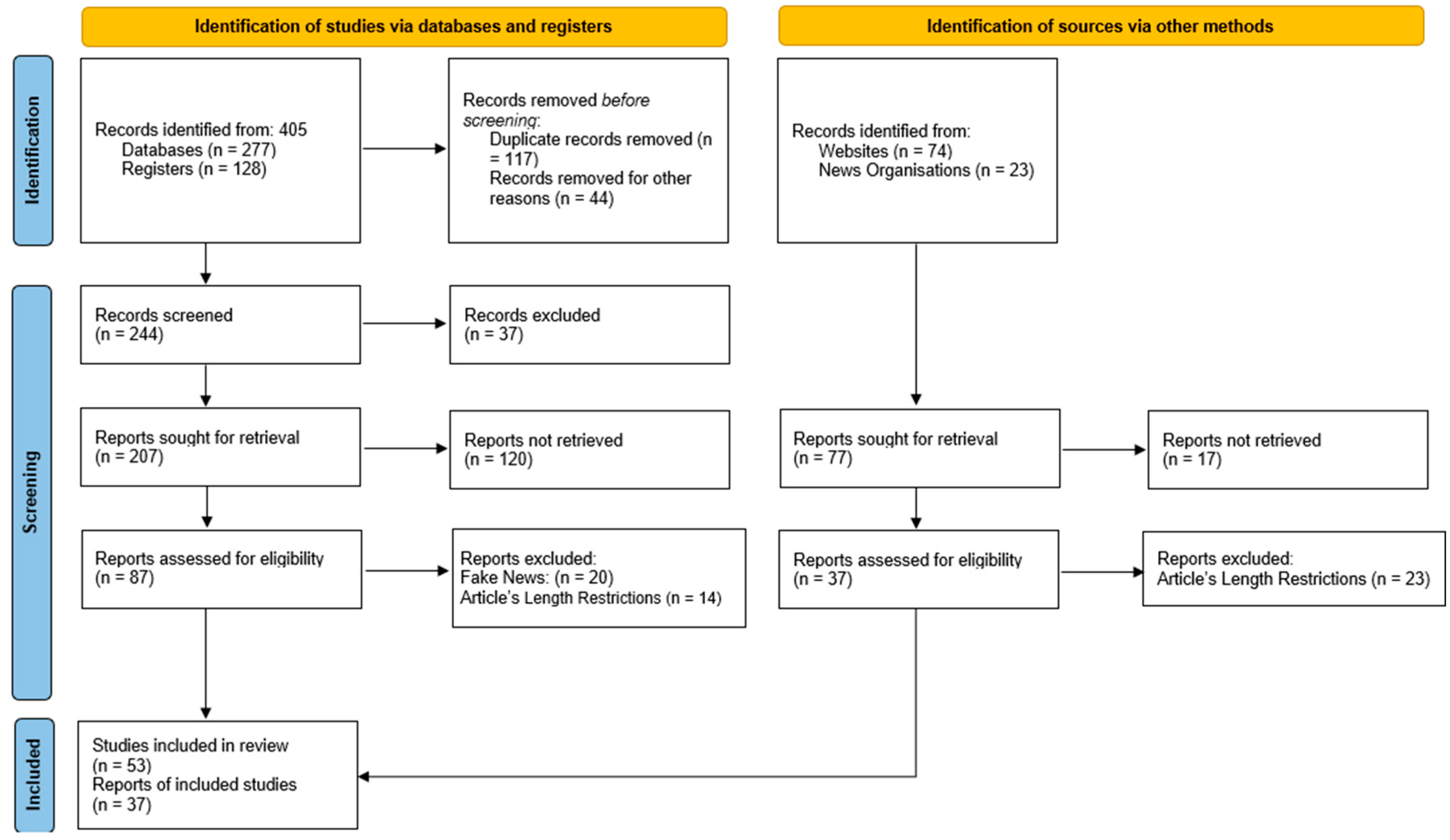

2.1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

2.2. Research Strategy and Data

- Academic Articles: Academic research in the field of business, human rights, and sustainability is well-represented. For instance, studies like those by Bartley (2018), which examine private authority in the global economy, and Jamali and Karam (2018), focusing on corporate social responsibility in developing countries, provide a strong theoretical foundation for the role of corporations in global supply chains (Bartley 2018; Jamali and Karam 2018). Other important contributors include LeBaron and Lister (2021), who explore ethical audits and the supply chains of global corporations (LeBaron and Lister 2021);

- Regulatory Documents: Regulatory frameworks, such as the Modern Slavery Act of both the Australian Government (2018) and the UK Government (2015), highlight the legal measures taken by different nations to address labor exploitation and modern slavery in global supply chains (Australian Government 2018; UK Government 2015). Similarly, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act by the US Congress (2010) introduces conflict minerals regulations, contributing to corporate social responsibility in global industries (US Congress 2010);

- Industry Reports: Several industry reports focus on the sustainability practices and transparency measures within global supply chains. For example, the OECD (2023a) guidelines on responsible business conduct provide comprehensive recommendations for companies engaging in international trade (OECD 2023a). Reports by the Global Reporting Initiative (2020) and World Bank (2020) further emphasize sustainability and transparency in supply chain management (Global Reporting Initiative 2020; World Bank 2020);

- Institutional Publications: Publications from institutions like Amnesty International (2016) and the Clean Clothes Campaign (2024) bring attention to the human rights issues within global supply chains, especially in industries with vulnerable labor forces, such as palm oil production and garment manufacturing (Amnesty International 2016; Clean Clothes Campaign 2024). These reports highlight the challenges of ensuring ethical practices in complex global networks.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Directive: Purpose and Scope

3.2. Key Provisions

3.3. Affected Entities

3.4. Potential Negative Impact on Entrepreneurial Activity

3.4.1. Initial Implementation Costs

3.4.2. Ongoing Compliance Costs

3.4.3. Administrative Burdens

3.4.4. Financial Strain on SUs and SMEs

3.4.5. Competitive Disadvantage

3.5. Potential Positive Impact on Entrepreneurial Activity

3.5.1. Long-Term Benefits

3.5.2. Opportunities for New Ventures

3.6. Influence on Ecosystems

3.6.1. Supply Chain Management

3.6.2. Collaboration and Network Effects

3.6.3. Regional Variations

3.7. Comparative Analysis with Other Regulations

3.7.1. Global Standards

3.7.2. Lessons from Non-EU Countries

3.8. Policy Recommendations

3.8.1. Support Mechanisms

3.8.2. Policy Enhancements

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amnesty International. 2016. The Great Palm Oil Scandal: Labour Abuses Behind Big Brand Names. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa21/5184/2016/en/ (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Archer, Phil, Karel Charvat, Mariano Navarro, La Cruz, Carlos A. Iglesias, John J O’Flaherty, Tomas Robles, and Dumitru Roman. 2022. Linked Open Data for environment protection in Smart Regions. In CORDIS: European Commission. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/603824/reporting (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Lauren Z., and Andrea Cipriani. 2018. How to carry out a literature search for a systematic review: A practical guide. BJPsych Advances 24: 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. 2018. Modern Slavery Act 2018. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2018A00153 (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Bachev, Hrabrin. 2007. Inclusion of Small-Scale Dairy Farms in Supply Chain in Bulgaria (A Case from Plovdiv Region). SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafilemba, Fidel, Timo Mueller, and Sasha Lezhnev. 2014. The Impact of Dodd-Frank and Conflict Minerals Reforms on Eastern Congo’s Conflict. Enough Project. Available online: https://www.enoughproject.org/files/Enough%20Project%20-%20The%20Impact%20of%20Dodd-Frank%20and%20Conflict%20Minerals%20Reforms%20on%20Eastern%20Congo%E2%80%99s%20Conflict%2010June2014.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Bartley, Tim. 2018. Rules Without Rights: Land, Labor, and Private Authority in the Global Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bohinc, Rado. 2014. Corporate social responsibility: (A European legal perspective). Canterbury Law Review 20: 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnitcha, Jonathan, and Robert McCorquodale. 2017. The Concept of ‘Due Diligence’ in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. European Journal of International Law 28: 899–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, Nicolas, Nadia Bernaz, Gabrielle Holly, and Olga Martin-Ortega. 2024. The EU Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (CSDDD): The Final Political Compromise. Business and Human Rights Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, Karin. 2024. Accountability in the EU for Corporate Human Rights and Environmental Harm: A Tale of Two Systems or Potential for Complementary Twinning? European Union Law Review 35: 429–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clean Clothes Campaign. 2024. 11 Years Since the Rana Plaza Collapse: Factories Are Safer, But the Root Causes of Tragedy Persist. Clean Clothes Campaign. April 24. Available online: https://cleanclothes.org/news/2024/11-years-since-the-rana-plaza-collapse-factories-are-safer-but-the-root-causes-of-tragedy-persist (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Cooper, Chris, Andrew Booth, Jo Varley-Campbell, Nicky Britten, and Ruth Garside. 2018. Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: A literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology 18: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, Tracey, James Guthrie, and John Dumay. 2022. Management controls and modern slavery risks in the building and construction industry: Lessons from an Australian social housing provider. The British Accounting Review 55: 101098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenduran, Gökçe, Eda Kemahlioğlu-Ziya, and Jayashankar M. Swaminathan. 2012. Product Take-Back Legislation and Its Impact on Recycling and Remanufacturing Industries. In Sustainable Supply Chains. International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Edited by Tonya Boone, Vaidyanathan Jayaraman and Ram Ganeshan. New York: Springer, vol. 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Banking Authority. 2020. Sustainable Finance: Market Practices. Available online: https://www.eba.europa.eu/sites/default/files/document_library/Sustainable%20finance%20Market%20practices.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- European Commission. 2022. Proposal for a Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/documents-register/detail?ref=COM(2022)71&lang=en (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- European Commission. 2023. Making Mandatory Human Rights and Environmental Due Diligence Work for all. International Partnerships—European Commission. Available online: https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/publications-library/making-mandatory-human-rights-and-environmental-due-diligence-work-all_en (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- European Environment Agency. 2020. The European Environment—State and Outlook 2020. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/soer-2020 (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- European Innovation Council and SMEs Executive Agency. n.d. Support for SMEs. Available online: https://eismea.ec.europa.eu/programmes/single-market-programme/support-smes_en (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- European Parliament. 2021. Corporate Due Diligence and Corporate Accountability. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2021-0073_EN.html (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- FAO. 2023. The State of Food and Agriculture 2023. Revealing the True Cost of Food to Transform Agrifood Systems. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: http://www.fao.org/publications/sofa/2014/en/ (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Feigerlová, Monika. 2024. Seminar of CIRED (The Czech Academy of Sciences). Centre International de Recherche sur l’Environnement et le Développement (CIRED). Available online: https://www.centre-cired.fr/en/seminaire-du-cired-monika-feigerlova-the-czech-academy-of-sciences-2/ (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Fisher, Jonathan. 2018. Impacts of Environmental Regulation on Sustainable Economic Growth. Journal of Business Economics 9: 749–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giegerich, Thomas. 2022. Supply Chains Responsibilities in the “Democratic and Equitable International Order”—The Tasks for the European Union and Its Member States. European Law Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjølberg, Maria. 2009. Measuring the immeasurable? Constructing an index of CSR practices and CSR performance in 20 countries. Scandinavian Journal of Management 25: 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. 2020. GRI Standards. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Horsley, Tanya, Orvie Dingwall, and Margaret Sampson. 2011. Checking reference lists to find additional studies for systematic reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 8: MR000026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM. n.d. Sustainability Solutions. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/sustainability (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- International Energy Agency. 2021. Renewable Energy Market Update 2021. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewable-energy-market-update-2021 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- International Finance Corporation. 2015. Managing Environmental and Social Performance. World Bank Group. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/mgrt/esms-handbook-general-v21.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- International Labour Organization. n.d. International Labour Standards and Human Rights. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/international-labour-standards-and-human-rights (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- International Monetary Fund. 2024. World Economic Outlook Update: July 2024. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2024/07/16/world-economic-outlook-update-july-2024 (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Ioannou, Ioannis, and George Serafeim. 2012. What drives corporate social performance? The role of nation-level institutions. Journal of International Business Studies 43: 834–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, Dima, and Charlotte Karam. 2018. Corporate social responsibility in developing countries as an emerging field of study. International Journal of Management Reviews 20: 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2017. Act on Promotion of Female Participation and Career Advancement in the Workplace. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en/laws/view/3018/en (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Korka-Knuts, Heli. 2024. Evaluating Corporate Accountability for Human Rights Violations: The (Uncertain) Efficacy of Administrative Sanctions Under the EU Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. European Union Law Review 2024: 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourula, Arno, Niccolò Pisani, and Ans Kolk. 2017. Corporate sustainability and inclusive development: Highlights from international business and management research. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 24: 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. 2023. The EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. Available online: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2023/02/the-eu-corporate-sustainability-due-diligence-directive.html (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Kus, Agnieszka, and Dorota Grego-Planer. 2021. A Model of Innovation Activity in Small Enterprises in the Context of Selected Financial Factors: The Example of the Renewable Energy Sector. Energies 14: 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBaron, Genevieve, and Jane Lister. 2021. Ethical Audits and the Supply Chains of Global Corporations. International Labour Review 160: 15–40. Available online: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/96303/1/Global-Brief-1-Ethical-Audits-and-the-Supply-Chains-of-Global-Corporations.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Mak, Chantal. 2022. Corporate sustainability due diligence: More than ticking the boxes? Journal of International Business and Law 102: 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfrino, Marianna. 2024. Blockchain Innovation for Sustainable Supply Chain Management under EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) Regulation. International Journal of Business and Technology Administration 2: 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Ortega, Olga. 2018. Due Diligence, Reporting and Transparency in Supply Chains. In The Human Rights Responsibilities of Business. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, Dirk, and Jeremy Moon. 2008. “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review 33: 404–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, Swen, and Reinhard Prügl. 2021. Digital transformation: A review, synthesis and opportunities for future research. Management Review Quarterly 71: 233–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natural Resources Canada. 2023. Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act. Available online: https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/our-natural-resources/minerals-mining/extractive-sector-transparency-measures-act/18180 (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- New, Stephen John. 2015. Modern slavery and the supply chain: The limits of corporate social responsibility? Supply Chain Management 20: 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, Justine, and Gregory Bott. 2018. Global supply chains and human rights: Spotlight on forced labour and modern slavery practices. Australian Journal of Human Rights 24: 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2011. OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2013. OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas: Second Edition. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2018. OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct. Available online: https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/OECD-Due-Diligence-Guidance-for-Responsible-Business-Conduct.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- OECD. 2021. OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2021 Issue 1. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2023a. OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2023/06/oecd-sme-and-entrepreneurship-outlook-2023_c5ac21d0.html (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- OECD. 2023b. OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct. OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-guidelines-for-multinational-enterprises-on-responsible-business-conduct_81f92357-en.html (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- OECD. n.d. ESG Investing: Practices, Progress and Challenges. OECD. Available online: https://search.oecd.org/daf/fin/financial-markets/esg-investing.htm (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Ottman, Jacquelyn A., Edwin R. Stafford, and Cathy L. Hartman. 2006. Avoiding Green Marketing Myopia: Ways to Improve Consumer Appeal for Environmentally Preferable Products. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 48: 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partzsch, Lena. 2024. Campaigning for Greater Accountability in Global Supply Chains. Environmental Politics 29: 344–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Micah D. J., Casey Marnie, Heather Colquhoun, Chantelle M. Garritty, Susanne Hempel, Tanya Horsley, Etienne V. Langlois, Erin Lillie, Kelly K. O’Brien, Özge Tunçalp, and et al. 2021. Scoping reviews: Reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Systematic Reviews 10: 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiedynok, Valeriia. 2023. “Safe Harbour” in the Proposal for Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. Economic and Law Review 4: 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Michael E., and Mark R. Kramer. 2011. Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review 89: 62–77. Available online: https://hbr.org/2011/01/the-big-idea-creating-shared-value (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Prezioso, Maria, and Maria Coronato. 2013. Sustainability in business practice: How competitiveness is changing in Europe. Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 5: 57+. Available online: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A338327894/AONE?u=anon~1b60dcb8&sid=googleScholar&xid=be0570e1 (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Saberi, Sara, Mahtab Kouhizadeh, Joseph Sarkis, and Lejia Shen. 2018. Blockchain technology and its relationships to sustainable supply chain management. International Journal of Production Research 57: 2117–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaguida, Barbara Maria Moreira Dante. 2023. Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Proposal and the 2024 European Parliament Elections. Amadeus International Law Review 7: 101–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAP. n.d. Sustainability Control Tower. Available online: https://www.sap.com/products/scm/sustainability-control-tower.html (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Sarkar, Amoudip N. 2013. Promoting Eco-Innovations to Leverage Sustainable Development of Eco-Industry and Green Growth. European Journal of Sustainable Development 2: 171–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S. Prakash, Terrence F. Martell, and Mert Demir. 2017. Enhancing the role and effectiveness of corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports: The missing element of content verification and integrity assurance. Journal of Business Ethics 144: 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shift Project. 2014. Remediation, Grievance Mechanisms, and the Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights. Available online: https://shiftproject.org/resource/remediation-grievance-mechanisms (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Simons, Penelope. 2015. Selectivity in law-making: Regulating extraterritorial environmental harm and human rights violations by transnational extractive corporations. In Law and the Global Economy. Edited by Penelope Simons. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 254–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solodovnik, Olesia. 2022. Institutional Framework and Experience of Implementing Non-Financial Reporting of Companies in the European Union. Infrastructure of the Market 71: 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Supply Chain Initiative. 2020. Global Supply Chain Management and Sustainability. Available online: https://www.theconsumergoodsforum.com/initiatives/sustainable-supply-chain-initiative (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Szmelter-Jarosz, Agnieszka. 2022. Specifics of Closed Loop Supply Chain Management in the Food Sector. Journal of Reverse Logistics 1: 14–19. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313895849_Specifics_of_Closed_Loop_Supply_Chain_Management_in_the_food_sector (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Taylor, Kathryn S., Kamal R. Mahtani, and Jeffrey K. Aronson. 2021. Summarising good practice guidelines for data extraction for systematic reviews and meta-analysis. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 26: 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorens, Morgane, Nadia Bernaz, and Otto Hospes. 2024. Advocating for the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive Against the Odds: Strategies and Legitimation. Journal of Common Market Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlakson, Tannis, Joann F. De Zegher, and Eric F. Lambin. 2018. Companies’ contribution to sustainability through global supply chains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115: 2072–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, Andrea C., Erin Lillie, Wasifa Zarin, Kelly K. O’Brien, Heather Colquhoun, Danielle Levac, David Moher, Micah D. J. Peters, Tanya Horsley, Laura Weeks, and et al. 2018. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 169: 467–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK Government. 2015. Modern Slavery Act 2015. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/30/contents/enacted (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- UN Global Compact. n.d. The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- UNCTAD. 2020. World Investment Report 2020: International Production Beyond The Pandemic. Available online: https://unctad.org/webflyer/world-investment-report-2020 (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- UNICEF. 2012. Children in Hazardous Work: What We Know, What We Need to Do. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/media/349936/download (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment. 2021. PRI Annual Report 2021. Available online: https://www.unpri.org/annual-report-2021 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- United Nations. 2011. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- US Congress. 2010. Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-111publ203/pdf/PLAW-111publ203.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Ventura, Livia. 2021. Supply chain management and sustainability: The new boundaries of the firm. University Law Review 26: 599–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, Livia. 2023. Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and the New Boundaries of the Firms in the European Union. European Business Law Review 34: 239–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2020. Doing Business 2020: Comparing Business Regulation in 190 Economies. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/32436 (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- World Bank. 2021a. Extractive Industries Overview. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/overview (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- World Bank. 2021b. Agricultural Innovation Systems: An Investment Sourcebook. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/pt/140741468336047588/pdf/672070PUB0EPI0067844B09780821386842.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- World Economic Forum. 2020. Global Gender Gap Report. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- World Economic Forum. 2021. The Global Risks Report 2021. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2021 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

| Key Provisions | Description | Article Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Due Diligence Measures | Companies must integrate comprehensive due diligence measures into their corporate policies to identify, avoid, mitigate, and account for harmful human rights and environmental impacts. This includes conducting risk assessments and implementing preventive and corrective actions. | Article 6 |

| Stakeholder Engagement | Companies are required to engage with stakeholders, such as workers, civil society, and trade unions, to ensure that those potentially affected by operations are involved in the due diligence process. | Article 6 |

| Reporting Requirements | Firms must publicly report on their due diligence activities, including risks identified, measures taken, and outcomes, in an annual statement published on their website by 30 April each year. | Article 11 |

| Corrective Action Plans | When adverse impacts are identified, companies must take corrective actions to neutralize the impact or minimize its extent. This may include providing compensation or seeking assurances from business partners for compliance. | Article 8 |

| Grievance Mechanisms | Companies must establish effective grievance mechanisms, allowing individuals and businesses to submit complaints regarding harmful impacts. These complaints should be addressed promptly and transparently. | Article 9 |

| Monitoring and Continuous Improvement | Companies are required to carry out periodic assessments of their operations and value chains to evaluate the effectiveness of their due diligence measures. Based on the findings, companies must update their policies to remain aligned with evolving standards and risks. | Article 10 |

| Affected Entities | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Large Enterprises | Companies with more than 500 employees and a net worldwide turnover exceeding EUR 150 million. These enterprises, often influential in global supply chains, are expected to implement comprehensive due diligence. | Article 2 (European Union 2022) |

| High-Impact Sectors | Companies with more than 250 employees and a net worldwide turnover of over EUR 40 million, where at least 50% of turnover is generated from high-risk industries. | Article 2 (European Union 2022) |

| Textiles and Apparel | The sector faces challenges related to labor rights violations, unsafe working conditions, and environmental impacts. The Rana Plaza tragedy highlighted these issues within global supply chains. | Clean Clothes Campaign (2024) |

| Agriculture and Food | Industries involved in agriculture, forestry, and food production, often dealing with challenges such as land use, deforestation, and labor rights. The palm oil industry exemplifies the need for oversight. | Amnesty International (2016); FAO (2023) |

| Extractive Industries | Mining and resource extraction sectors are known for environmental damage, community displacement, and human rights abuses. The Democratic Republic of Congo’s mining industry is a key example. | World Bank (2021a); UNICEF (2012) |

| Manufacturing and Trade of Chemicals and Fuels | Involves primary metals manufacturing and wholesale trade of minerals and intermediate products. The sector’s environmental impacts, such as pollution, demand comprehensive due diligence. | OECD (2018); European Environment Agency (2020) |

| Aspect | Description | Impact on SUs and SMEs |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Implementation Costs | Substantial investments in IT systems, due diligence frameworks, and training to comply with new mandates. | High upfront costs in IT and employee training; necessary to implement due diligence frameworks. |

| Ongoing Compliance Costs | Continuous monitoring, reporting, audits, and certifications for compliance. | Recurring costs for audits, certifications, compliance teams, and external consultants. |

| Administrative Burdens | Significant documentation, record keeping, and stakeholder engagement requirements. | Increased resource allocation for administrative tasks and maintaining comprehensive records. |

| Financial Strain on SUs and SMEs | Cash flow challenges and potential difficulties in securing financing. | Higher financial strain due to limited resources and risk of non-compliance penalties. |

| Competitive Disadvantage | Smaller businesses struggle to compete with larger firms that benefit from economies of scale. | Challenges in meeting compliance requirements, limiting competitive positioning and market access. |

| Long-Term Benefits | Potential long-term benefits through sustainable practices and improved resource efficiency. | Enhanced reputation, access to new markets, and lower long-term operational costs. |

| Opportunities for New Ventures | Growth opportunities in sustainability consulting, compliance software, and training services. | New business prospects in offering solutions for compliance and sustainability. |

| Influence on Ecosystems | Supply chain management and stakeholder engagement changes due to higher transparency requirements. | Need for stronger supplier relationships and enhanced transparency throughout the supply chain. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dempere, J.; Udjo, E.; Mattos, P. The Entrepreneurial Impact of the European Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100266

Dempere J, Udjo E, Mattos P. The Entrepreneurial Impact of the European Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(10):266. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100266

Chicago/Turabian StyleDempere, Juan, Eseroghene Udjo, and Paulo Mattos. 2024. "The Entrepreneurial Impact of the European Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 10: 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100266

APA StyleDempere, J., Udjo, E., & Mattos, P. (2024). The Entrepreneurial Impact of the European Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence. Administrative Sciences, 14(10), 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100266