Abstract

The main objective of this study is to investigate a solution for the current lack of skilled workers in Europe and to optimize the utilization of expertise. For this qualitative study, 36 semi-structured interviews were conducted (with a purposive sample of financially independent (soon-to-be) retirees and employers). The thematic analysis revealed (1) on both the employer’s and recruiter’s side, there are many stereotypes and prejudices, as well as a lack of creativity about how to integrate these highly motivated specialists into the organization’s workforce; (2) Employees, retirees and employers where asked: what could be the motivation to employ retirees, what could be the benefits, what could be the drawbacks. The results also indicate that searching for intellectual challenges and solving them with a team of co-workers is one of the main attractions for senior experts. We identified six main patterns for unretirement choices: learning and intellectual challenges, applying expertise, public perception of retirees, belonging and social connections, compensating for loss of status, and feeling appreciated. Appreciating, valuing, and channeling this drive to solve present-day problems independent of a person’s chronological age should be self-evident for organizations and societies.

1. Introduction

Governments across Europe are fighting to raise the statutory retirement age: those in favor say we cannot let experts retire while companies struggle to replace their skills and labor (Eatock 2019). Those “against” argue that employees who have worked for decades should not be made to pay for the lack of effective human resource management by decision-makers or inadequate pension systems (Barslund et al. 2019). Moreover, the contributions of senior experts are questioned based on age-related performance realities and prejudices (Federal Ministry for Family Affairs 2023; Jungmann et al. 2020; Vasconcelos 2015; Wegge et al. 2012).

The literature provides a variety of terms, definitions, and formats for late or post-career work, such as “phased” or “partial retirement”, which Lassen et al. have analyzed and categorized (Lassen and Vrangbæk 2021). Journals and books for the public started using the term “unretirement” for older people, reversing their retirement decisions as far back as 1994 (Fyock and Stangor 1994) Fyock, Jack, and Charles Stangor. 1994. The role of memory biases in stereotype maintenance. British Journal of Social Psychology 1994). In the United States of America, “unretirement” is understood as a bridging occupation between full-time work and retirement or even as a lifestyle choice beyond financial motivation (Lee 2022). The first time academia adopted the term “unretirement” was Maestas (2010). Authors who use the term “unretirement” present the definitions and usage they have encountered in the literature and—finding that the criteria vary—offer their definitions that will apply to their specific work (Kanabar 2015; Lassen and Vrangbæk 2021; Lee 2022).

The ability to retain senior experts can be crucial for the performance of organizations. These organizations must implement a culture that recognizes and promotes the workforce’s competencies, experience, and potential. Lee (2022) adds that “…focusing development programs only on a select number of «high potentials» undervalues the contribution of a large part of the workforce [and] might put unnecessary pressure on the high performers …”. It also frustrates those in the workforce who have contributed to the organization’s growth and are willing to continue doing so. An organization’s awareness of ageism and willingness to develop and implement age-inclusive policies and practices contribute to the employer’s attractiveness (Gignac et al. 2022). To this study, “unretirement” is considered any form of work that a healthy, well-educated, financially independent expert who has retired from regular full-time employment is being paid for at a level that would also be attractive for non-retired persons.

Focusing on Germany as one of the largest economies in Europe (Statista 2024), his study aims to research conditions for all parties to consider a third option: choice. Analyzing data from scientific literature and topic-specific semi-structured interviews with three perspectives (retirees, senior employees, and employers/recruiters), this study builds on the current discussion of whether (or if) the continued or re-employment of senior experts could contribute to easing the lack of skilled labor in organizations.

Using an exploratory approach through Grounded Theory, we have focused on the motivations of organizations to consider continuing employment or rehiring senior experts, the requirements of senior experts to consider continuing, and the plans and expectations of employees about ten years before their legal retirement age.

The analysis of the semi-structured interviews allows us to identify six main drivers for unretirement choices: learning and intellectual challenges, applying expertise, public perception of retirees, belonging and social connections, compensating for loss of status, and feeling appreciated.

The literature review led to the formulation of the following research questions:

- (a)

- Faced with a lack of competence in current European labor markets, what is keeping financially independent senior experts who continue looking for intellectual challenges from offering their competencies?

- (b)

- Why are there still organizations that have not found ways to keep or rehire these valuable assets?

2. Literature Review

Previous research has highlighted that post-retirement employment appeals to employees and employers if expectations and requirements are aligned (Tur-Sinai et al. 2022).

A study by Wöhrmann et al. (2016) identifies four post-retirement work choices: voluntary work, same-employer paid work, other-employer paid work, or self-employed paid work based on a quantitative study performed in one logistics company. The authors link Schwartz’s four basic value dimensions, namely, self-transcendence, self-enhancement, conservation, and openness to change, to retirement decisions and offer suggestions to organizations on how to attract individuals that are open to post-retirement work (Schwartz 2017; Wöhrmann et al. 2016). Similarly, Sullivan and Al Ariss (2019) offer suggestions for retirees’ post-retirement employment from an organization’s point of view (Sullivan and Al Ariss 2019).

Armstrong-Stassen and her research colleagues continue to document since 2005 that the opportunity to learn and develop is essential for senior experts to consider staying in their organization (Armstrong-Stassen 2008a, 2008b, 2008c; Armstrong-Stassen and Cameron 2005; Armstrong-Stassen and Schlosser 2008, 2011; Armstrong-Stassen and Templer 2005; Armstrong-Stassen and Ursel 2009; Kerr and Armstrong-Stassen 2011).

Potentially positive effects of senior personalities in teams—be it in Board Rooms or innovations teams—seem to depend on several contributing factors such as team climate, leadership style, level of age discrimination or appreciation of age diversity in the organization, which can be improved through dedicated training (Beji et al. 2021; Janz et al. 2012; Jungmann et al. 2020; Pesch et al. 2015; Schneid et al. 2016; Tshetshema and Chan 2020; Wegge and Schmidt 2009).

While Pelled et al. (1999) demonstrated that age-diverse teams had fewer emotional conflicts than more homogeneous teams, MacCurtain et al. (2010) contradicted these findings, as did Pesch et al. (2015). Based on their research, Boehm et al. (2011) confirm that findings across studies regarding the effects of age diversity are inconsistent and suggest that organizations will have to find customized solutions to integrate the expertise of senior experts to benefit their organization’s specific needs (Wu et al. 2019).

Weber and Loichinger (2022) emphasize a significant heterogeneity regarding the continued ability and willingness to perform and conform based on education levels, confirming Lassen and Vrangbæk’s (2021) caution to stereotype retirees. Berthel and Becker (2022) emphasize the necessity of continuously evaluating the competencies needed in a changing work environment and appreciate that life, work experience, and subject matter expertise are not interchangeable when evaluating employees’ contributions.

How successfully organizations use the diversity of their workforce is very much dependent on the leaders’ capability to manage diverse teams, and this is strongly influenced by their values (Duns 2016; Leenen et al. 2019; Saha et al. 2020; Silvestri and Veltri 2020). Barnett and Karson (1989) discussed if the ethical behavior of leaders is connected to age or career stage or reflects current societal values to which Copeland (2014) adds her literature review from 2014 after observing “…extensive, evasive and disheartening leadership failures” at the start of the 21st century. These developments in organizations’ culture and behaviors and societies’ values have shaped the working life of current retiree candidates.

Chungkham et al. (2023) challenge the validity of software packages that promise to help understand, calculate, and predict working life duration. There will not be an easy answer, so organizations and policymakers need to consider that diversity (Weber and Loichinger 2022).

Research on psychological safety defines trust and mutual respect as the critical components of a climate in which people are “comfortable being (and expressing) themselves” (Edmondson 2003; Gignac et al. 2022). Research links employees’ trust in the organization and its members to individual and organizational performance (Edwards and Cable 2009; Scheuer and Loughlin 2019). Armstrong-Stassen and Schlosser (2008) summarize studies and own data to confirm that “affective commitment” to their organization induces older employees to consider staying with their organization, especially when they tend to seek development opportunities.

Retirees are looking for meaningful work, flexibility regarding time commitment and content, the opportunity to contribute to an organization’s success, and stimulating social interaction (Kerr and Armstrong-Stassen 2011; Kollmann et al. 2020; Lassen and Vrangbæk 2021).

3. Method

The methodology followed for this study is best described by Elharidy et al. (2008, p. 151) in that we listened to the “…multiple voices [and perspectives] in the data…” and as much as Scapens (2008, p. 915) demands that the knowledge of accounting researchers be combined “with the craft knowledge of accounting practitioners” we compared the findings from the literature review with the findings from our qualitative research.

The topic of this study is in flux: attitudes, perceptions, regulations, individual plans and capabilities, and the environment in which retirement takes place are in a constant process of change. Aware of the complexity and uniqueness of this research approach, this awareness was integrated into the interpretation and analysis of data, using the exploratory approach of Grounded Theory as a protection against unconscious bias, continually reflecting on the study approach, challenging the configuration of the study and perfecting the methods of analyzing and interpreting data. Adding a qualitative research design to the systematic literature review, a series of semi-structured interviews were carried out, and a thematic narrative analysis centered on themes and topics were applied instead of using language or actions (Saunders et al. 2019).

3.1. Participants

The sample is purposive, and participants were chosen as they were seen to be able to contribute to the answer to the research questions (Elharidy et al. 2008; Scapens 2008).

When selecting interview participants from the workers’ and pensioners’ perspectives, we chose individuals who do not have financial needs and who consider it possible to work beyond the legal retirement age. At the outset of this research paper, we decided to focus on white-collar experts and exclude physically demanding jobs from our study as these deserve their own dedicated research (Davis and Dotson 1987; Loveridge 2017), instead building on research which concluded that older workers’ preferences and skills are best suited to office work (Acemoglu et al. 2022).

From the workers’ perspective, participants at a legal retirement age of around ten years were selected.

This option was sustained on the German Semi-Retirement Act, introduced in 1996. This law had the purpose of providing a framework for employees and employers for a gradual transition from full-time employment to retirement while ensuring financial stability for the employee by regulating the payment of certain benefits. Eligible are employees that have reached the age of 55 and with this cutoff, many companies and employees start discussing options when the employee is in his/her early 50s (AltTZG 1996—Altersteilzeitgesetz/German Semi-Retirement Law 1996).

As the third part of our triangulation approach, the perspective of the employer/recruiter was added to the study. The distribution of the participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of study participants based on perspective and gender.

Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 each give an overview of the study participants’ perspective as well as their (former) industry and position.

Table 2.

Overview of study participants with perspective “employee” including industry and position.

Table 3.

Overview of study participants with perspective “employer/recruiter” including industry and position.

Table 4.

Overview of study participants with perspective “(early) retiree” including industry and position.

The study participants were coded alphanumerically with “F” or “M” to identify their gender, “em” from the employee perspective, “er” from the recruiter or employer perspective, and “rt” from the retiree perspective. Citations will look as follows (examples):

- emF01 represents a female employee,

- erF06 represents a female employer/recruiter,

- rtM05 represents a male retiree.

3.2. Instruments

Semi-structured interviews allow for collecting ideas, expectations, stipulations, proposals, suggestions, and experiences without filters. This method requires constant vigilance so that the criteria of objectivity, reliability/dependence, generalizability /transferability, and validity/credibility are met. As the interviews were conducted over 12 months, data collection and analysis were carried out in parallel (Saunders et al. 2019). This required continuous checking of the data: for some items, we referred to previous interviews to confirm or adjust the initial interpretation of that data. For other items, data saturation was reached early in the process, and additional interviews confirmed the validity of this study’s set-up (for example, the benefits of preparing for a smooth transition from working life to retirement over a sufficiently long period).

The three separate interview protocols (Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7) for each group of participants in the study were developed based on the literature review and feedback from the test interviewees. Employees, retirees and employers were asked: what could be the motivation to employ retirees, what could be the benefits, what could be the drawbacks.

Table 5.

Interview protocol 1—Questions to persons responsible for strategic decisions regarding HR and overall workforce deployment—English Version—excerpt.

Table 6.

Interview protocol 2—Questions to employees—English Version—excerpt.

Table 7.

Interview protocol 3—Questions to retirees—English Version—excerpt.

3.3. Procedures

Systematic literature review (SLR). A systematic literature review was conducted between November 2022 and March 2024, starting with the search term “unretirement”, providing 15 references. After analyzing these articles, other Scopus searches were added with the keywords “senior experts” and “retirement”, followed by “age-diversity” and spelling variations of “team performance”. The initial search covered an exhaustive examination of studies on a global scale, ensuring a comprehensive perspective on the topic. As this study focuses on Europe, with a particular emphasis on Germany, publications from the OECD, the European Union and German ministries were added. There is awareness of the potential for profession- and country-specific conclusions, which may arise due to the different cultural and regulatory frameworks unique to each country and/or profession.

To be included in the analysis in this document, a reference had to fulfil the following requirements:

- -

- The main emphasis is on studies with sample groups of adults in Europe with white-collar jobs.

- -

- Peer-reviewed article or book chapter available on the Scopus or Web of Science databases (editorials or book reviews are not accepted).

- -

- Include at least two of the keywords listed above in the title, abstract, or article.

- -

- Adding information relevant to our study.

The following criteria were added manually to exclude publications that did not fall within the scope of the topic to be explored:

- -

- Research centered on physically demanding professions and

- -

- In Germany civil servants do fall under labour law regulations but they differ in important parts from the labour law applied to employees in private organizations.

Qualitative research: semi-structured interviews focusing on three perspectives. Between January and December 2023, 36 interviews were carried out centered on the following three perspectives:

- (a)

- Healthy, financially prepared, highly educated (early) retirees;

- (b)

- Healthy, financially prepared, highly educated senior employees; and

- (c)

- Employers/recruiters.

Most of the interviews were conducted via the collaboration tool Zoom and recorded with the consent of the interviewee. They were conducted in German or English and lasted between 30 to 90 min depending on the number of interruptions or tangents the participants followed.

The first author refined translations using DeepL as a basis. Amberscript was used for an initial rough audio file transcription, which we then prepared for analysis.

In cases where it was not possible to record the interviews digitally, they were documented manually during the interview. We tried to strike a balance between conducting this openly and, at the same time, discreetly to encourage interviewees to respond openly and to feel that their time and ideas were appreciated. After the interview was completed, it was transcribed and handwritten in MS Word, and the documentation was offered to the interview partner for review and confirmation to support the validity of our research.

4. Results

Yes, retirees have earned their right to enjoy their retirement. For some, that means never seeing the inside of an organization or company again, focusing their time, experience, and energy on topics and activities they put aside during their working lives or have recently discovered (rtM11).

Research shows that some retirees would choose the business world; they would value having more options to stay involved and that societies would benefit from giving senior experts more scope to apply their expertise and maturity (Barslund et al. 2019; Federal Ministry for Family Affairs 2023; OECD 2020).

As it was discovered that it is the treatment experienced in the latter stages of regular employment that encourages or dissuades senior experts from even considering working beyond the legal retirement age, research on age diversity was analyzed. It was considered that these studies assessed the impact that senior experts had and experienced in their pre-retirement phase.

The first topic on which the participants’ attitudes in our research varied was addressed: compensation. Some see financial compensation as an accepted means of communicating appreciation for work performed or services rendered—regardless of the age of the service provider (emF02, emF10b, emF11b, emF12, rtF13, emM02b, emM03, rtM08, rtM09, emM12, emM17b). Others focus on greater flexibility in how or when they provide their expertise (rtF07, rtF08, emF09) or consider it their public duty to generously share their expertise for free after having been paid to apply it during their professional lives (emF03b, rtF04, emF09, rtM07, rtM10).

Another significant finding is that professionals who had the chance to “slide into retirement” through part-time models or the home office period triggered during the COVID pandemic experience the transition from work into retirement much more smoothly: the understanding of how much of one’s identity and how many relationships are tied to the professional life are as essential to consider in post-retirement planning as experiencing society’s perception of (part-time) retirees. That includes expectation management at home and the need to renegotiate the distribution of roles and tasks (rtF04, rtM07, rtM09). Moreover, “…it is certainly very sensible, already with a few years before retirement … to think carefully about what activities you want to build up afterwards because for many things the foundation should already be laid before you stop …” (rtF05b). “…I also know pensioners who have lost their sense of purpose and status, which is hard for them. Now, they cannot find their way back in. Being willing and able to perform is like a muscle you must train …” (emM06).

4.1. A Taboo Subject?

This research shows that the perception in society of someone leaving the community of full-time employees is still influenced by the belief that retirees enjoy the luxury of not having to do anything. “And that was also important to me, to cut, not to extend the profession somehow …, but to say clearly that was it, as far as professional things are concerned …” (rtM11).

Suppose the retiree wants to continue to apply their expertise in a more flexible set-up. In that case, they are perceived as financially challenged, unable to let go, or encouraged to volunteer with “like-minded lonely souls”. As one of the study participants reflected, “… we have to comprehend that our generation has created the current decision-makers, we have molded them, we have set an example of “working life” …” (emM06).

Some admire those who are still working to a certain extent and who are still doing a good job as managers or specialists. “I think that many people who still have a very, very good job beyond retirement age are also a little envied …” (erM14).

4.2. Retiree Perspective

Organizations and society are still adjusting to retirees wanting to continue contributing and learning—learning to apply their expertise in a new field with new tools and adjust to new roles and environments.

“Especially … for managers, people responsible for years, there is nothing. The exception is …; I would say, the top level, for whom age was not an issue, who, because of their great networks … you find them on supervisory boards. However, that is a world of its own. So, I would say for managers at the executive level, not top level, it is quite difficult to find something adequate after retirement, and it is time for a change.”(rtF08)

“I think expert advice is easier to take than advice from leaders. An expert is an expert no matter how old he is. With a leader, people always wonder if he or she can take on the role change from leader to advisor.”(rtM05)

“… I had a small quantity of a suspicion that the head of … was not comfortable with the idea that he would have someone sitting there in his team who was superior to him in terms of seniority and experience …”(rtF05b)

4.3. Employer Perspectives

An organization’s performance depends on the workforce’s performance, and personal diagnostics stress the necessary fit between task and personality (Schuler 2014). The interviewees see age diversity as the responsibility of both Human Resources (HR) and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives. In scientific papers age-diversity in combination with CSR is covered with a view of board composition but we have not seen publications yet on how the recruitment of senior people across the organization supports CSR objectives.

“I do not see a scarcity of candidates in the middle or upper levels of management but at the basis of an organization. Retirees with an academic background who have not reached middle or higher management positions at that time are probably not the ones we would be keen to hire as they represent the percentage of the staff that have not invested in their development over their career.”(erM14)

“I see a challenge in that … the senior people, on the one hand, have to be very selfless so that they do not get the spotlight, but rather the project leader-to-be or the manager-to-be or the person who has just become one. I see this as a challenge because people who have already gained experience in most cases do not suddenly give it up; they somehow need it for themselves and their lives because, in the end … the other person, the new leader, has the success that he or she celebrates. So that could be the challenge …”(erM04aa)

“I see this group of people working primarily on projects. …Because I believe that this group of people has a special motivation. They do not necessarily need the extra Euro … but still like to feel challenged, … and want something for their heads and want to be in life and not on the sand court every day to play boules, to use a metaphor. This means I would try to address this group of people primarily through the content and their values.”(erF06)

4.4. Win-Win

“…they put in their expertise, their steadiness and calmness, and at the same time, they got [topics] done by the young people that might have stressed them [the seniors] out …”(erF06)

“[What I appreciate about senior experts is their] ability to separate, to filter … and [that] can lead to the more important topics being dealt with in a prioritized way …. I see a very, very big strength in it, … a certain calmness … to identify the right topics and to tackle them properly. …At some point, the “shocks” come and go and are repetitive. That is when you identify patterns. You have references on which you can somehow compare situations and say: Is this bigger than that? … [but] this chronological age. …of the person is just very irrelevant in most cases, I am quite honest … it is not so much about age, in my opinion, but it is really about how you build teams.”(erM04aa)

“We pensioners retire early. We are still in good health, and I think we are still mentally fit. I would not have retired if I had not realized I was now the oldest person in the company. Moreover, at some point, you should not work two or three years longer when you are the oldest. …But …I believe that companies, our employees, and our entire economy would benefit greatly if all pensioners who are physically and mentally able to do so were to pass on their experience for another 10 per cent. I think that would be immeasurably valuable …”(rtM10)

“If you want to groom skilled workers to stay on as long as possible or even return from retirement, you must involve them in project work, innovation circles, etc. You need to keep incentivizing them and give them the feeling that they are doing something valuable for the company. So, they are not just routinely going to work every day but are always looking forward to their day. If you manage to do that, then you have the right kind of people that you can keep on board until you have developed the younger generation …”(erM14)

“…sometimes it is … essential to look for the … typical pillars … we are not looking for stars, we are looking for people … to bring stability to the teams … I would be much more open to offering a part-time job model to a Senior than to a Junior in order to get or keep access to their expertise and experience …”(erM17a)

4.5. Themes and Patterns Identified

Beyond the fact that senior experts appreciate development opportunities in their current organizations (see Literature Review in this study), our study adds that highly educated retirees do not just want to continue contributing and using the skills they acquired over their working lives (Table 8). They seek to share their expertise and learn to apply it to a new field or environment.

Table 8.

Themes and patterns identified.

In a nutshell, this study shows that the motivation of senior experts to consider staying involved in the workforce varies.

Based on an exploratory study (Falckenthal et al. 2023), we identified 10 patterns that influence the successful integration of senior experts beyond the legal retirement age into the workforce: legal and regulatory challenges; personality; social status; brain-food; self-fulfillment; experience; individualized terms and agreements; remaining up to date while sharing wisdom; recognition; paid tasks versus voluntary work.

By adding, refining, and relating the data, initial findings were confirmed and relationships identified. Axial coding revealed the following six patterns:

- Belonging and social connections.

- Learning and intellectual challenges.

- Applying expertise.

- Public perception of retirees.

- Compensating for loss of status.

- Feeling appreciated.

If their professional life has been very intense since the beginning of their career, some participants are aware that for a smooth transition into the next phase of their life, they need activities that can pick up this drive (emM17b, emF03b) or they have to step back already while still in a regular job (rtM08, rtM11, emF12, emF10b).

In the last step of selective coding, we identified three main elements for the successful integration of senior experts beyond the legal retirement age into the workforce taking all three perspectives into account:

- (a)

- Individual values of the employer and employee.

- (b)

- The seeking and offering of intellectual challenges.

- (c)

- Something we call “balanced engagement” offering the senior social interaction within a team in return for contributing calmness and maturity in addition to subject matter expertise.

5. Discussion

Organizations are stifling their growth by neglecting to continuously and purposefully integrate senior experts into their workforce.

The ambition to build on decades of expertise, apply that experience to new environments, and add new pertinent knowledge to their existing vast repertoire are the critical drivers for senior experts who consider unretirement.

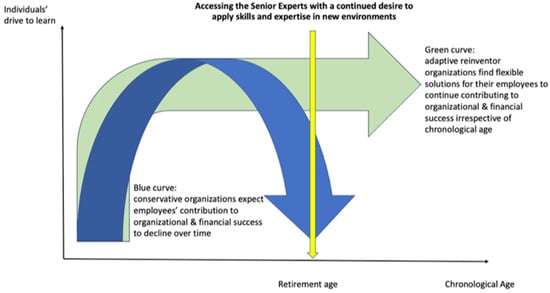

In Germany, there are names for senior experts, such as “Best Ager” and “Silver Society” (Lohmüller and Greiff 2022; Regnet 2019). Putting aside the biases these names conjure, some senior experts are willing and able to continue working beyond their legal retirement age. In addition, large and medium-sized companies have come up with various solutions and examples of accessing and applying senior expert expertise (firms we call adaptive reinventors). However, too few companies still have the framework to manage the above (Figure 1) actively.

Figure 1.

Accessing senior experts with a continued desire to apply skills and expertise in new environments.

If companies consider rehiring retirees, why have they let go of that skill set in the first place? Because too often, employment practices are still rooted in the belief that a career can only go upward—and that the only attractive career progression is upward. After years of growing numbers of employees choosing sabbaticals mid-career and whole bookshelves on work–life balance, few companies have followed these insights with more creative employment policies. “…We should create new rules that do not cement the current status quo but create new opportunities.” (emM06).

Why do seasoned employees who enjoy working accept early retirement plans only to work freelance as pensioners or dive into time-consuming hobbies or volunteer work? Often, they are quite unprepared for the challenge of structuring their days and weeks, and they underestimate the effort to find customers and the need to adjust their own schedule to customers’ availability.

This study confirms research that beyond financial motivations, the aspiration for social recognition, belonging, and contribution drives retirees to consider staying involved in the workforce (Kollmann et al. 2020; Lee 2022; Schröder 2023).

The interviews support previous studies that connect senior experts’ experience and openness to new ideas (Beji et al. 2021; Hafsi and Turgut 2013). While Armstrong-Stassen et al. (2012) focus on the return of early retirees to their former employer, their findings support our and other authors’ research: Being in the privileged position to choose the conditions under which they apply their vast expertise, organizations need to offer senior experts flexible ways to contribute to the organization’s success (Armstrong-Stassen et al. 2012; Boehm et al. 2011).

Personal values guide individuals’ attitudes, behaviors, and decision-making, and they play a crucial role in the context of retirement and how individuals approach this transition. One employer interviewee summarizes her talks with several former employees, saying that retirement candidates who are approached before leaving the company about options to stay involved are much more motivated to discuss terms than candidates who have not been asked while still employed. The latter feel like their contributions are not appreciated until the company experiences the loss of their skills.

Attitudes, biases, expectations, and realities in our society and organizations impact the appeal of continued or re-employment for senior experts. Research on the (lack of) integration of Corporate Social Responsibility goals and Human Resources practices points to the potential of leadership development and workforce education to support culture change efforts (Jang and Ardichvili 2020; Principi et al. 2015). Several authors confirm the importance of leadership competency for the success of diverse teams (Boehm et al. 2011; Scheuer and Loughlin 2021). A study on age diversity among board members confirms a positive relationship with CSR performance but otherwise inconsistent impact on company performance (Gardiner 2022). Additionally, studies show significant heterogeneity regarding the continued ability and willingness to perform based on education levels (Platts et al. 2019; Weber and Loichinger 2022).

Attitudes, biases, expectations, and realities in our society and organizations impact the appeal of continued or re-employment for seniors. Senior experts could be a valuable source of expertise for organizations in the current labor market. “…jobs in which complex information is processed and that require a high level of education and training are less prone to digital change shortly” (Lorenz et al. 2023). These might be the niches companies cannot afford to ignore for available expertise. Few job descriptions reflect this.

As a framework for our research, we analyzed the legal and regulatory options for post-retirement employment as they are currently valid in Germany and adjacent economies. Existing regulation allows for several contractual possibilities whose implications for both sides of the contract must be carefully considered. As one research participant phrased it: “… I would hire them as a trainer, as an instructor and as a sparring partner, …to keep them “at arm’s length” from my labor law obligations.” We leave the discussion of possible measures to facilitate post-retirement employment to the authors of legal journals. Inspiration might be found among our Nordic neighbors (Halvorsen 2021). Finally, this is a cross-sectional study (a photograph of a moment in time) and might serve as a basis for a longitudinal study. Future research might confirm or disconfirm our research results or instead might focus on changes in attitude regarding an increasingly aging workforce—a common reality in more developed countries.

6. Conclusions

The definition of “retirement” and the expectations of how retirees spend their time constantly change. Just as the choice of profession varies from person to person, so do retirement plans. They are very much influenced by several factors, not least the individuals’ education level.

Sliding into retirement with part-time contracts was designed to reduce HR costs. Now, organizations must take this flexibility one step further and redesign task distribution across the workforce based on skills and expertise, not chronological age. Considering the impact of digitization and the constantly changing requirements that workers must fulfil, incumbents might feel threatened by senior experts’ scope of expertise and maturity. At the same time, senior experts need to plan their post-retirement as carefully as their career to shape that phase actively and not feel frustrated by a lack of opportunities. Moreover, as one of our interviewees summarized: “The bandwidth of options you have as a retiree is …a function of your fitness… Whether you have the freedom and the choices, or your opportunities are limited due to fitness constraints that shape your everyday life…” (emM06).

Independent of age, workers expect more flexibility from organizations regarding location, time frame, and weekly working hours. The workplace equipment and ergonomics have become much more adaptable to individual needs and preferences. It is not a question of age to expect the workplace and times to be customizable. By actively developing age-diversity competence across all generations, employees in all stages of their careers might benefit, and managers responsible for HR and recruiting decisions would have a wider pool from which to staff open positions.

The benefits and challenges attributed to diverse teams also apply to the dimension of “age.” Company cultures and HR practices must be addressed for this development to succeed. Financially independent retirees are more selective in choosing work engagements as they pay more attention to bringing their objectives to the workplace. At the same time, maintaining curiosity and openness is a crucial prerequisite for all parties involved.

From our research, we find that the following demographics might be interesting to study in the future: having a partner versus being single, having to care for family members (parents, partners, children, or relatives), and intercultural dimensions of age diversity—to name but a few. Further access to the topic may be by analyzing if and how personality traits (e.g., based on the OCEAN model) influence a senior expert’s availability and employability.

This study might also benefit younger workers who may become more aware of what awaits them as they grow older. It might influence their career choices and career trajectory by encouraging them to reflect on personal values, lifegoals, and what it means to have a longer career.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.F., C.F. and M.A.-Y.-O.; methodology, B.F., C.F. and M.A.-Y.-O.; software, B.F.; validation, B.F., C.F., A.P.-M. and M.A.-Y.-O.; formal analysis, B.F., C.F., A.P.-M. and M.A.-Y.-O.; investigation, B.F., C.F., A.P.-M. and M.A.-Y.-O.; resources, B.F., C.F., A.P.-M. and M.A.-Y.-O.; data curation, B.F., C.F., A.P.-M. and M.A.-Y.-O.; writing—original draft preparation, B.F., C.F., A.P.-M. and M.A.-Y.-O.; writing—review and editing, B.F., C.F., A.P.-M. and M.A.-Y.-O.; visualization, B.F., C.F., A.P.-M. and M.A.-Y.-O.; supervision, B.F., C.F. and M.A.-Y.-O.; project administration, B.F., C.F., A.P.-M. and M.A.-Y.-O.; funding acquisition, A.P.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical analysis and approval were waived for this study, as all the interviewees had to read and sign an informed consent form before being interviewed. Interviewees would only be interviewed if they agreed. If they disagreed, they would not be interviewed. The interviewees were thus informed about the purpose of the study and the confidentiality of the results. No names of the interviewees were to be mentioned; nor any organizations they are, or were, perhaps linked to.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the lead author. The data are not publicly available because, in their informed consent, the participants were informed that the data would be confidential and that individual responses would never be known, as the data analysis would be of all the participants combined.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acemoglu, Daron, Nicolaj Søndergaard Mühlbach, and Andrew J. Scott. 2022. The rise of age-friendly jobs. Journal of the Economics of Ageing 23: 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AltTZG 1996—Altersteilzeitgesetz/German Semi-Retirement Law. 1996. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/alttzg_1996/BJNR107810996.html (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Armstrong-Stassen, Marjorie. 2008a. Factors associated with job content plateauing among older workers. Career Development International 13: 594–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Stassen, Marjorie. 2008b. Human resource practices for mature workers—And why aren’t employers using them? Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 46: 334–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Stassen, Marjorie. 2008c. Organisational practices and the post-retirement employment experience of older workers. Human Resource Management Journal 18: 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Stassen, Marjorie, and Andrew Templer. 2005. Adapting training for older employees. The Canadian response to an aging workforce. Journal of Management Development 24: 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Stassen, Marjorie, and Francine Schlosser. 2008. Benefits of a supportive development climate for older workers. Journal of Managerial Psychology 23: 419–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Stassen, Marjorie, and Francine Schlosser. 2011. Perceived organizational membership and the retention of older workers. Journal of Organizational Behavior 32: 319–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Stassen, Marjorie, and Nancy D. Ursel. 2009. Perceived organizational support, career satisfaction, and the retention of older workers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 82: 201–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Stassen, Marjorie, and Sheila Cameron. 2005. Factors related to the career satisfaction of older managerial and professional women. Career Development International 10: 203–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Stassen, Marjorie, Francine Schlosser, and Deborah Zinni. 2012. Seeking resources: Predicting retirees’ return to their workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology 27: 615–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, John H., and Marvin J. Karson. 1989. Managers, values, and executive decisions: An exploration of the role of gender, career stage, organizational level, function, and the importance of ethics, relationships and results in managerial decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics 8: 747–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barslund, Mikkel, Robert Anderson, Markus Bönisch, Andreas Cebulla, Hans Dubois, Charlotte Fechter, Tobias Göllner, Nathan Hudson-Sharp, Johannes Klotz, Gerd Naegele, and et al. 2019. Policies for an Ageing Workforce Work-Life Balance, Working Conditions and Equal Opportunities Report of a CEPS-NIESR-FACTAGE and Eurofound Conference. Available online: www.factage.eu (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Beji, Rania, Ouidad Yousfi, Nadia Loukil, and Abdelwahed Omri. 2021. Board Diversity and Corporate Social Responsibility: Empirical Evidence from France. Journal of Business Ethics 173: 133–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthel, Jürgen, and Fred G. Becker. 2022. Personal-Management—Grundzüge für Konzeptionen betrieblicher Personalarbeit, 12th ed. Stuttgart: Schäffer-Poeschel. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, Stephan, Miriam K. Baumgaertner, David J. G. Dwertmann, and Florian Kunze. 2011. Age diversity and its performance implications-Analysing a major future workforce trend. In From Grey to Silver: Managing the Demographic Change Successfully. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chungkham, Holendro Singh, Robim S. Högnäs, Jenny Head, Paola Zaninotto, and Hugo Westerlund. 2023. Estimating Working Life Expectancy: A Comparison of Multistate Models. SAGE Open 13: 21582440231177270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, Mary Kay. 2014. The Emerging Significance of Values Based Leadership: A Literature Review. International Journal of Leadership Studies 8: 105–35. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Paul O., and Charles O. Dotson. 1987. Job performance testing: An alternative to age discrimination. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 19: 179–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duns, Stephen. 2016. Corporate social responsibility and leadership. International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research 14: 3211–31. [Google Scholar]

- Eatock, David. 2019. Demographic outlook for the European Union 2019. EPRS—European Parliamentary Research Service. Available online: https://dspace.ceid.org.tr/handle/1/1820 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Edmondson, Amy. 2003. Psychological Safety, Trust, and Learning in Organizations: A Group-level Lens. Trust and Distrust in Organizations: Dilemmas and Approaches 12: 239–72. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Jeffrey R., and Daniel M. Cable. 2009. The Value of Value Congruen ce. Journal of Applied Psychology 94: 654–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elharidy, Ali M., Brian Nicholson, and Robert W. Scapens. 2008. Using grounded theory in interpretive management accounting research. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management 5: 139–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falckenthal, Bettina, Manuel Au-Yong-Oliveira, and Cláudia Figueiredo. 2023. They Learned, They Grew, They Succeeded-So Why Retire? The Gift of Experience. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10773/38161 (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth. 2023. Older Persons and Demographic Change. Available online: https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/meta/en/older-persons (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Fyock, Jack, and Charles Stangor. 1994. The role of memory biases in stereotype maintenance. British Journal of Social Psychology 33: 331–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, Elliroma. 2022. What’s age got to do with it? The effect of board member age diversity: A systematic review. Management Review Quarterly 74: 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, Monique A. M., Julie Bowring, Faraz V. Shahidi, Vicki Kristman, Jill Cameron, and Arif Jetha. 2022. Workplace Disclosure Decisions of Older Workers Wanting to Remain Employed: A Qualitative Study of Factors Considered When Contemplating Revealing or Concealing Support Needs. Work, Aging and Retirement 10: 174–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafsi, Taïeb, and Gokhan Turgut. 2013. Boardroom Diversity and its Effect on Social Performance: Conceptualization and Empirical Evidence. Journal of Business Ethics 112: 463–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, Bjorn E. 2021. High and rising senior employment in the Nordic countries. European Journal of Workplace Innovation 6: 130–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Soebin, and Alexandre Ardichvili. 2020. Examining the Link Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Human Resources: Implications for HRD Research and Practice. Human Resource Development Review 19: 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, Katharina, Claudia Buengeler, Robert A. Eckhoff, Astrid C. Homan, and Sven C. Voelpel. 2012. Leveraging age diversity in times of demographic change: The crucial role of leadership. In Handbook of Research on Workforce Diversity in a Global Society: Technologies and Concepts. Hershey: IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungmann, Franziska, Jürgen Wegge, Susanne C. Liebermann, Birgit C. Ries, and Klaus-Helmut Schmidt. 2020. Improving Team Functioning and Performance in Age-Diverse Teams: Evaluation of a Leadership Training. Work, Aging and Retirement 6: 175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanabar, Ricky. 2015. Post-retirement labour supply in England. Journal of the Economics of Ageing 6: 123–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, Gerry, and Marjorie Armstrong-Stassen. 2011. The Bridge to Retirement. The Journal of Entrepreneurship 20: 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, Tobias, Christoph Stöckmann, Julia M. Kensbock, and Anika Peschl. 2020. What satisfies younger versus older employees, and why? An aging perspective on equity theory to explain interactive effects of employee age, monetary rewards, and task contributions on job satisfaction. Human Resource Management 59: 101–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassen, Aske Juul, and Karsten Vrangbæk. 2021. Retirement transitions in the 21st century: A scoping review of the changing nature of retirement in Europe. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life 15: 39–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Zeewan. 2022. Returning to work: The role of soft skills and automatability on unretirement decisions. Journal of the Economics of Ageing 22: 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenen, Louise, Adelai Van Heerden, Phelela Ngcingwana, and Lindiwe Masole. 2019. A model to select a leadership approach for a diverse team. Paper presented at the European Conference on Research Methods in Business and Management Studies, Johannesburg, South Africa, June 20–21; pp. 182–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmüller, Eva Kkatharina, and Katharina Greiff. 2022. Generationensensible Personal- und Karriereentwicklung—Ansätze und Instrumente für eine erfolgreiche Umsetzung in Unternehmen. In Generationen-Management. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, pp. 225–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, Hanno, Fabian Stephany, and Jan Kluge. 2023. The future of employment revisited: How model selection affects digitization risks. Empirica 50: 323–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveridge, Stephanie. 2017. Nurse manager role stress. Nursing Management 48: 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCurtain, Sarah, Patrick C. Flood, Nagarajan Ramamoorthy, Michael A. West, and Jeremy F. Dawson. 2010. The Top Management Team, Reflexivity, Knowledge Sharing and New Product Performance: A Study of the Irish Software Industry. Creativity and Innovation Management 19: 219–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestas, Nicole. 2010. Back to work: Expectations and realizations of work after retirement. Journal of Human Resources 45: 718–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2020. Promoting an Age-Inclusive Workforce. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelled, Lisa Hope, Kathleen M. Eisenhardt, and Katherine R. Xin. 1999. Exploring the black box: An analysis of work group diversity, conflict, and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly 44: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, Robin, Ricarda B. Bouncken, and Sascha Kraus. 2015. Effects of Communication Style and Age Diversity in Innovation Teams. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management 12: 1550029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platts, Loretta G., Laurie M. Corna, Diana Worts, Peggy McDonough, Debora Price, and Karen Glaser. 2019. Returns to work after retirement: A prospective study of unretirement in the United Kingdom. Ageing and Society 39: 439–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principi, Andrea, Paolo Fabbietti, and Giovanni Lamura. 2015. Perceived qualities of older workers and age management in companies: Does the age of HR managers matter? Personnel Review 44: 801–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnet, Erika. 2019. Best Agers—Arbeitssituation, Gesundheit und Karriereerwartungen. Available online: https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-hs-augsburg/1800 (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Rudolph, Cort W., Rachel S. Rauvola, and Hannes Zacher. 2018. Leadership and generations at work: A critical review. The Leadership Quarterly 29: 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, Raiswa, Shashi Kaskav, Roberto Cerchione, Rajwinder Singh, and Richa Dahiya. 2020. Effect of ethical leadership and corporate social responsibility on firm performance: A systematic review. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 409–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Mark N. K., Philip Lewis, Adrian Thornhill, and Alex Bristow. 2019. Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed. London: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Scapens, Robert W. 2008. Seeking the relevance of interpretive research: A contribution to the polyphonic debate. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 19: 915–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, Cara-Lynn, and Catherine Loughlin. 2019. The moderating effects of status and trust on the performance of age-diverse work groups. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship 7: 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, Cara-Lynn, and Catherine Loughlin. 2021. Seizing the benefits of age diversity: Could empowering leadership be the answer? Leadership & Organization Development Journal 42: 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneid, Matthias, Rodrigo Isidor, Holger Steinmetz, and Rüdiger Kabst. 2016. Age diversity and team outcomes: A quantitative review. Journal of Managerial Psychology 31: 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, Martin. 2023. Work Motivation Is Not Generational but Depends on Age and Period. Journal of Business and Psychology 39: 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, Heinz. 2014. Psychologische Personalauswahl, 4th ed. Göttingen: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 2017. The Refined Theory of Basic Values. In Values and Behavior. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing, pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, Antonella, and Stefania Veltri. 2020. Exploring the relationships between corporate social responsibility, leadership, and sustainable entrepreneurship theories: A conceptual framework. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 585–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. 2024. Gross Domestic Product at Current Market Prices of Selected European Countries in 2023 (In Million Euros). September 17. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/685925/gdp-of-european-countries/ (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Sullivan, Sherry E., and Akram Al Ariss. 2019. Employment After Retirement: A Review and Framework for Future Research. Journal of Management 45: 262–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshetshema, Caspar T., and Kai-Ying Chan. 2020. A systematic literature review of the relationship between demographic diversity and innovation performance at team-level. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 32: 955–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur-Sinai, Aviad, Shosh Shahrabani, Ariela Lowenstein, Ruth Katz, Dafna Halperin, and Haya Fogel-Grinvald. 2022. What drives older adults to continue working after official retirement age? Ageing & Society 44: 1618–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, Anselmo Ferreira. 2015. Older workers: Some critical societal and organizational challenges. Journal of Management Development 34: 352–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, Frank, and Susanne Scheibe. 2013. A literature review and emotion-based model of age and leadership: New directions for the trait approach. The Leadership Quarterly 24: 882–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Daniela, and Elke Loichinger. 2022. Live longer, retire later? Developments of healthy life expectancies and working life expectancies between age 50–59 and age 60–69 in Europe. European Journal of Ageing 19: 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegge, Jürgen, and Klaus-Helmut Schmidt. 2009. The impact of age diversity in teams on group performance, innovation and health. In Handbook of Managerial Behavior and Occupational Health. London: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wegge, Jürgen, Franziska Jungmann, Susanne C. Liebermann, Meir Shemla, Brigit Claudia Ries, Stefan Diestel, and Schmidt Klaus.-Helmut. 2012. What makes age diverse teams effective? Results from a six-year research program. Work 41: 5145–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wöhrmann, Anne Marit, Ulrike Fasbender, and Jürgen Deller. 2016. Using Work Values to Predict Post-Retirement Work Intentions. Career Developent Quarterly 64: 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Jie, Orlando C. Richard, Xinhe Zhang, and Craig Macaulay. 2019. Top Management Team Surface-Level Diversity, Strategic Change, and Long-Term Firm Performance: A Mediated Model Investigation. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 26: 304–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, Lena, and Laurence Romani. 2004. When nationality matters. A study of departmental, hierarchical, professional, gender, and age-based employee groupings. Leadership preferences across 15 countries. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 4: 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).