Systematic Literature Review on Gig Economy: Power Dynamics, Worker Autonomy, and the Role of Social Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Q1: What is currently understood about power structures, worker autonomy, and the function of social networks within the gig economy? This involves analyzing how these networks operate and the support that they provide to gig workers.

- Q2: How does algorithmic management shape gig workers’ agency and their capacity for collective action? This question explores algorithms’ influence on workers’ autonomy, daily experiences, and opportunities for resistance.

- Q3: Where should future research on the gig economy focus to effectively address power imbalances and promote worker empowerment? To answer this, we propose a theoretical framework that identifies how gig workers can utilize their social networks to counteract the systemic power disparities embedded in platform-based labor models.

The Method

2. Research Methodology

Systematic Literature Review Methods

- What is known about the power dynamics, worker autonomy, and the role of social networks in the gig economy? This question aims to guide the discovery of the bibliometrics, characteristics, constructs, relationships, and themes in the gig economy labor dynamics domain. It seeks to uncover the current knowledge regarding how power is distributed between digital platforms and gig workers, how worker autonomy is influenced, and the significance of social networks in this context.

- How is algorithmic management’s impact on platform workers’ agency and collective action understood? This question aims to explore the theoretical frameworks, empirical contexts, and relations among stakeholders that have been used to understand the influence of algorithmic management on the autonomy and collective agency of gig laborers.

- Where should future research head to effectively address power imbalances and enhance worker empowerment through a comprehensive framework? This question is designed to identify the current literature gaps and suggest future research directions. It should also determine how the relations mapped in the literature can be understood in one framework.

| Algorithm 1. Pseudo code for bibliometric analysis process. | |

| Input: Excel file with authors’ names and citations references | |

| Output: Normalized bibliometric data and co-citation network | |

| Step 1: Bibliometric Data Collection | |

| Import the bibliometric data from the Excel file. | |

| Step 2: Authors’ Name and Citation Reference Normalization | |

| For each paper, normalize the authors’ names and citations: | |

| • Remove diacritics | |

| • Convert text to lowercase | |

| • Strip extra spaces | |

| Ensure consistency in citation formatting using the unicodedata library. | |

| Step 3: Remove Articles Without Bibliometric Data | |

| Filter and remove papers missing bibliometric data (e.g., no authors or citations). | |

| Step 4: Co-Citation Relationship Identification | |

| For each paper, extract cited references. | |

| For each reference, identify other papers citing the same reference. | |

| Create edges between papers that share at least one citation. | |

| Build a co-citation network with: | |

| • Nodes = Papers | |

| • Edges = Shared citations. | |

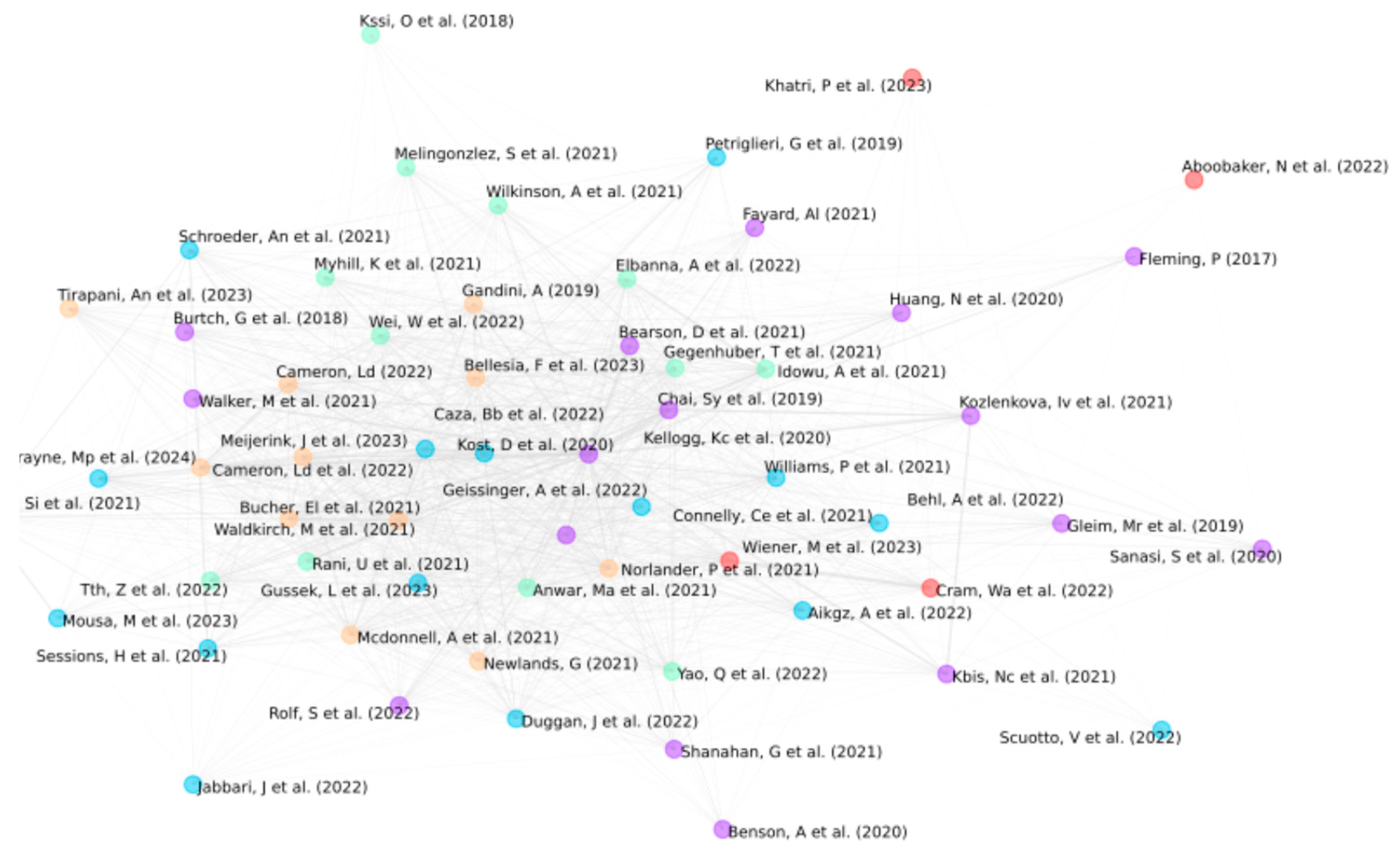

| Step 5: Community Detection with the Leiden Algorithm | |

| Convert the co-citation network into a graph structure. | |

| Apply the Leiden community detection algorithm to find clusters of related papers. | |

| Clusters represent groups of papers that share frequent citations. | |

| Step 6: Graph Visualization | |

| Use a spring layout to position nodes based on connectivity. | |

| Draw the graph with: | |

| • Different colors for each community (clusters). | |

| • Edge thickness reflecting the number of shared citations. | |

| Adjust labels to avoid overlap using the adjustText library. | |

| Step 7: Isolated Node Removal | |

| Remove papers that have no shared citations with others (isolated nodes). | |

| Step 8: Robustness and Sensitivity Checks | |

| Adjust inclusion/exclusion criteria (e.g., citation thresholds, year range). | |

| Rerun the community detection to validate consistency. | |

| Step 9: Final Graph Generation | |

| Generate the final visualization with clusters and labeled nodes. | |

- To test the impact of the inclusion criteria on the synthesized results, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by expanding the range of publication years to include studies published before 2009 and adjusting the keywords and Boolean search strings to capture a broader or narrower set of studies.

- To understand the influence of study quality on the synthesized results, we performed an analysis focusing exclusively on high-quality studies with robust study designs and comprehensive peer review status, as indicated by inclusion in the WOS.

- To guarantee that we captured the gig economy’s global nature, we analyzed our findings’ sensitivity to geographical (e.g., North America, Europe, Asia) and contextual differences, such as diverse types of gig work (e.g., ridesharing vs. delivery services).

3. Theoretical Reference

3.1. Systematic Literature Review on the Gig Economy’s Power Dynamics, Algorithmic Management, and Labor Relations

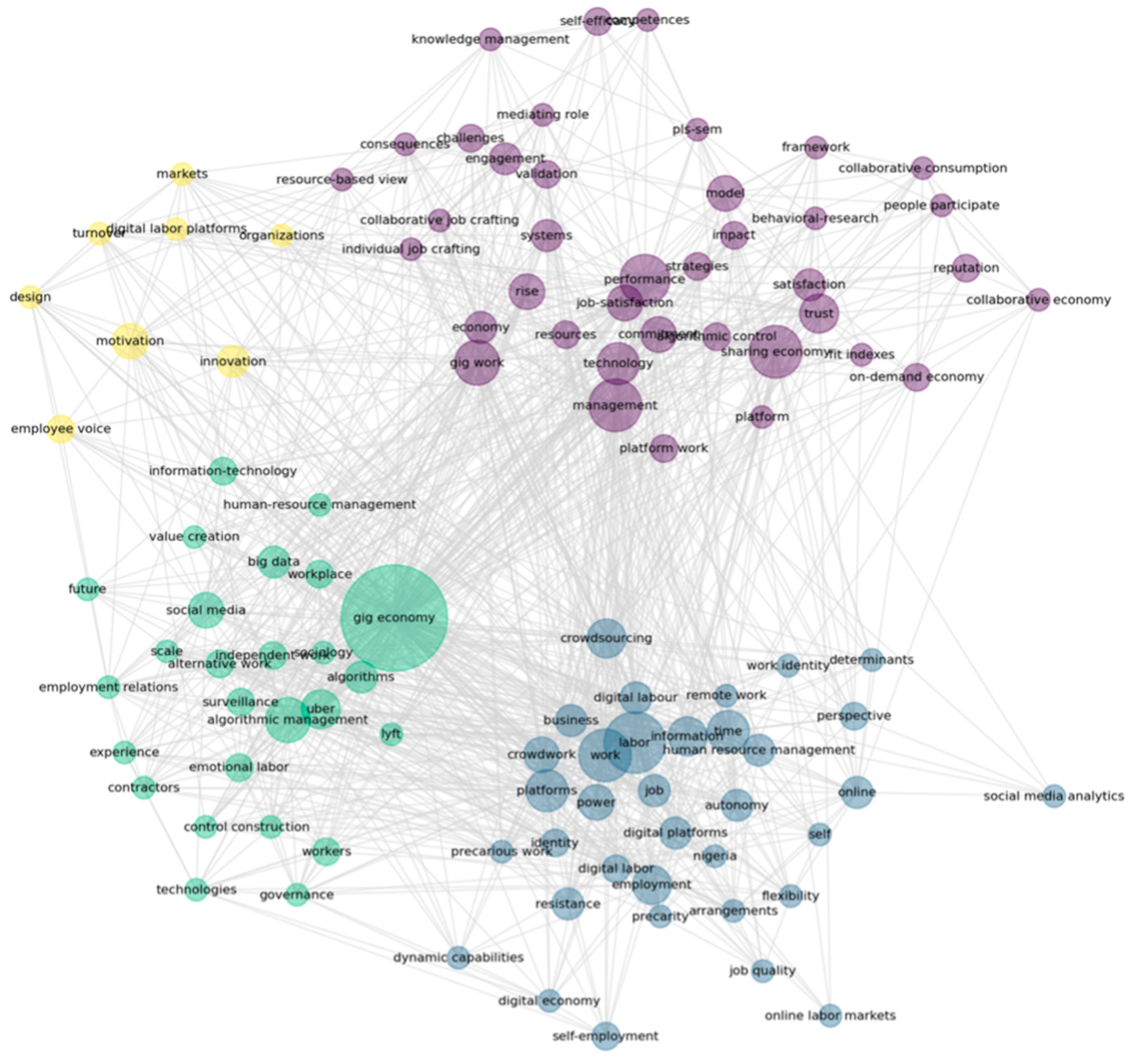

3.1.1. Keyword Analysis

- Power Imbalance Enforced by Algorithmic Management: Algorithms intensify the power imbalances between platforms and workers.

- Emotional and Psychological Impacts on Workers: Gig work affects workers’ emotional well-being and psychological state.

- Various Forms of Resistance: Workers employ different strategies to resist or cope with platform control.

3.1.2. Author and Citation Analysis

3.1.3. Emerging Trends and Potential Literature Gaps

4. Discussion

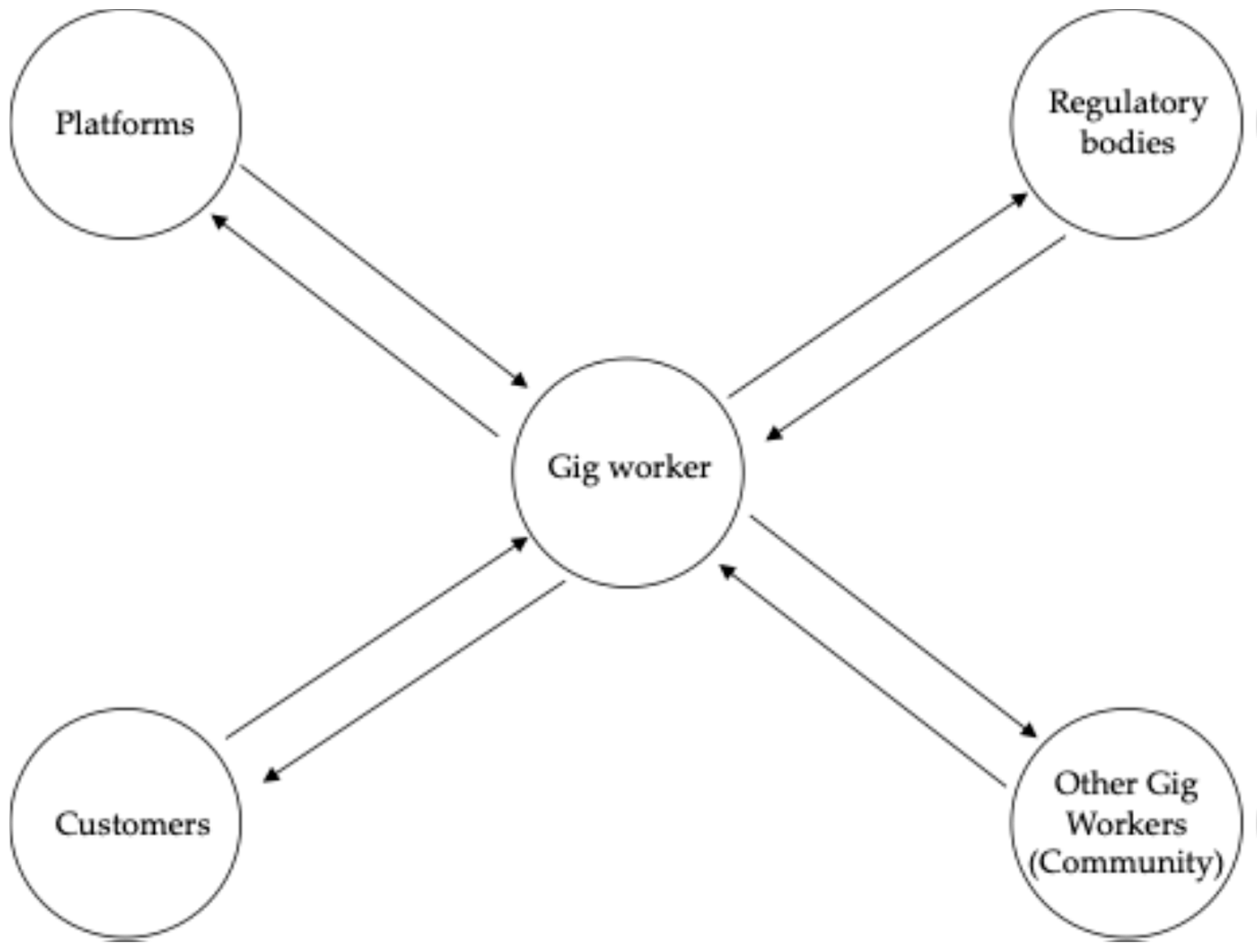

- Power imbalances and algorithmic control: Platforms wield significant power over gig workers through algorithmic management, leading to reduced autonomy and increased job insecurity. This control manifests through task assignments, performance evaluations, and surveillance mechanisms. Authors such as Kellogg et al. (2020) delve into how algorithmic management allows platforms to control workers by limiting their autonomy through individual performance evaluations and task assignments. In contrast, this study highlights how gig workers collectively counteract these power asymmetries.

- Collective agency and worker empowerment: Despite platforms’ overarching control, gig workers actively engage in resistance and collective strategies. Forming communities or networks, sharing knowledge, and collective bargaining are pivotal in enhancing their bargaining power and working conditions. The mechanisms that drive the collective action among gig workers are multifaceted, relying heavily on the informal social networks that form within platform ecosystems. These networks serve as conduits for the dissemination of tactical knowledge, such as methods for managing customer ratings, navigating platform policies, and organizing collective bargaining. For instance, Mechanical Turk workers have formed an online forum to assist individuals in navigating their ‘career’ on a platform and facilitate collective action (Johnston and Land-Kazlauskas 2018). These social networks facilitate both overt and covert forms of resistance, ranging from data obfuscation techniques to organized strikes aimed at disrupting platform operations

- Role of regulatory bodies: Effective regulation is essential for protecting gig workers’ rights and ensuring fair labor practices. Policymakers need to develop regulations that address job security, income stability, and worker protections tailored to the unique challenges of gig work. However, overly stringent regulations can have negative consequences, including increased informal work.

- Technological and social forces: The interplay between technological advancements and social dynamics significantly shapes the gig economy. Platforms use technology to manage and control workers, while workers leverage technology to connect, organize, and resist. Social forces, including cultural perceptions and community support, also play a critical role in shaping worker experiences and outcomes, creating supportive “holding environments” to navigate the emotional tensions created by precarious work.

4.1. Practical Implication

4.2. Research Limitations

4.3. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anwar, Mohammad Amir, and Mark Graham. 2021. Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Freedom, Flexibility, Precarity and Vulnerability in the Gig Economy in Africa. Competition and Change 25: 237–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascur, Juan Pablo, Suzan Verberne, Nees Jan van Eck, and Ludo Waltman. 2023. Academic Information Retrieval Using Citation Clusters: In-Depth Evaluation Based on Systematic Reviews. Scientometrics 128: 2895–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, Abhishek, Nirma Jayawardena, Alessio Ishizaka, Manish Gupta, and Amit Shankar. 2022. Gamification and Gigification: A Multidimensional Theoretical Approach. Journal of Business Research 139: 1378–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellesia, Francesca, Elisa Mattarelli, and Fabiola Bertolotti. 2023. Algorithms and Their Affordances: How Crowdworkers Manage Algorithmic Scores in Online Labour Markets. Journal of Management Studies 60: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, Eliane Léontine, Peter Kalum Schou, and Matthias Waldkirch. 2021. Pacifying the Algorithm—Anticipatory Compliance in the Face of Algorithmic Management in the Gig Economy. Organization 28: 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Lindsey D., and Hatim Rahman. 2022. Expanding the Locus of Resistance: Understanding the Co-Constitution of Control and Resistance in the Gig Economy. Organization Science 33: 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Sunyu, and Maureen A. Scully. 2019. It’s About Distributing Rather than Sharing: Using Labor Process Theory to Probe the ‘Sharing’ Economy. Journal of Business Ethics 159: 943–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherbakov, L., G. Galambos, R. Harishankar, S. Kalyana, and G. Rackham. 2005. Impact of Service Orientation at the Business Level. IBM Systems Journal 44: 653–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cram, W. Alec, Martin Wiener, Monideepa Tarafdar, and Alexander Benlian. 2022. Examining the Impact of Algorithmic Control on Uber Drivers’ Technostress. Journal of Management Information Systems 39: 426–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crayne, Matthew P., and Alice M. Brawley Newlin. 2023. Driven to Succeed, or to Leave? The Variable Impact of Self-Leadership in Rideshare Gig Work. International Journal of Human Resource Management 35: 98–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, James, Ultan Sherman, Ronan Carbery, and Anthony McDonnell. 2020. Algorithmic Management and App-work in the Gig Economy: A Research Agenda for Employment Relations and HRM. Human Resource Management Journal 30: 114–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, Christian F., Joakim Kembro, and Andreas Wieland. 2017. A New Paradigm for Systematic Literature Reviews in Supply Chain Management. Journal of Supply Chain Management 53: 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbanna, Amany, and Ayomikun Idowu. 2022. Crowdwork, Digital Liminality and the Enactment of Culturally Recognised Alternatives to Western Precarity: Beyond Epistemological Terra Nullius. European Journal of Information Systems 31: 128–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayard, Anne Laure. 2021. Notes on the Meaning of Work: Labor, Work, and Action in the 21st Century. Journal of Management Inquiry 30: 207–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Peter. 2017. The Human Capital Hoax: Work, Debt and Insecurity in the Era of Uberization. Organization Studies 38: 691–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galière, Sophia. 2020. When Food-Delivery Platform Workers Consent to Algorithmic Management: A Foucauldian Perspective. New Technology, Work and Employment 35: 357–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, Alessandro. 2019. Labour Process Theory and the Gig Economy. Human Relations 72: 1039–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gegenhuber, Thomas, Markus Ellmer, and Elke Schüßler. 2021. Microphones, Not Megaphones: Functional Crowdworker Voice Regimes on Digital Work Platforms. Human Relations 74: 1473–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissinger, Andrea, Christofer Laurell, Christina Öberg, Christian Sandström, and Yuliani Suseno. 2022. The Sharing Economy and the Transformation of Work: Evidence from Foodora. Personnel Review 51: 584–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, Mark R., Catherine M. Johnson, and Stephanie J. Lawson. 2019. Sharers and Sellers: A Multi-Group Examination of Gig Economy Workers’ Perceptions. Journal of Business Research 98: 142–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Keman, Jinhui Yao, and Ming Yin. 2019. Understanding the Skill Provision in Gig Economy from a Network Perspective: A Case Study of Fiverr. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 3: 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Hannah, and Chris Land-Kazlauskas. 2018. Organizing On-Demand: Representation, Voice, and Collective Bargaining in the Gig Economy. In Conditions of Work and Employment Series. Geneva: ILO. ISSN 2226-8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, Katherine C., Melissa A. Valentine, and Angéle Christin. 2020. Algorithms at Work: The New Contested Terrain of Control. Academy of Management Annals 14: 366–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, Anthony, Ronan Carbery, John Burgess, and Ultan Sherman. 2021. Technologically Mediated Human Resource Management in the Gig Economy. International Journal of Human Resource Management 32: 3995–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijerink, Jeroen, and Anne Keegan. 2019. Conceptualizing Human Resource Management in the Gig Economy: Toward a Platform Ecosystem Perspective. Journal of Managerial Psychology 34: 214–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijerink, Jeroen, and Tanya Bondarouk. 2023. The Duality of Algorithmic Management: Toward a Research Agenda on HRM Algorithms, Autonomy and Value Creation. Human Resource Management Review 33: 100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, James, and Paul Raekstad. 2023. Algorithmic Domination in the Gig Economy. European Journal of Political Theory 22: 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhill, Katie, James Richards, and Kate Sang. 2021. Job Quality, Fair Work and Gig Work: The Lived Experience of Gig Workers. International Journal of Human Resource Management 32: 4110–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newlands, Gemma. 2021. Algorithmic Surveillance in the Gig Economy: The Organization of Work through Lefebvrian Conceived Space. Organization Studies 42: 719–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norlander, Peter, Nenad Jukic, Arup Varma, and Svetlozar Nestorov. 2021. The Effects of Technological Supervision on Gig Workers: Organizational Control and Motivation of Uber, Taxi, and Limousine Drivers. International Journal of Human Resource Management 32: 4053–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, Fábio Lotti, Andrei Carlos Torresani Paza, Jefferson Luiz Bution, Masaaki Kotabe, Peter Kelle, Eduardo Pinheiro Gondim de Vasconcellos, Celso Claudio de Hildebrand e. Grisi, Martinho Isnard Ribeiro de Almeida, and Adalberto Americo Fischmann. 2022. A Model to Analyze the Knowledge Management Risks in Open Innovation: Proposition and Application with the Case of GOL Airlines. Journal of Knowledge Management 26: 681–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Justin, Weng Marc Lim, Aron O’Cass, Andy Wei Hao, and Stefano Bresciani. 2021. Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). International Journal of Consumer Studies 45: O1–O16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petriglieri, Gianpiero, Susan J. Ashford, and Amy Wrzesniewski. 2019. Agony and Ecstasy in the Gig Economy: Cultivating Holding Environments for Precarious and Personalized Work Identities. Administrative Science Quarterly 64: 124–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilatti, Gustavo, Cristian Candia, Alessandra Montini, and Flávio L. Pinheiro. 2023. From Co-Location Patterns to an Informal Social Network of Gig Economy Workers. Applied Network Science 8: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, Uma, and Marianne Furrer. 2021. Digital Labour Platforms and New Forms of Flexible Work in Developing Countries: Algorithmic Management of Work and Workers. Competition and Change 25: 212–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenelle, Alexandrea J. 2019. ‘We’re Not Uber:’ Control, Autonomy, and Entrepreneurship in the Gig Economy. Journal of Managerial Psychology 34: 269–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolf, Steven, Jacqueline O’Reilly, and Marc Meryon. 2022. Towards Privatized Social and Employment Protections in the Platform Economy? Evidence from the UK Courier Sector. Research Policy 51: 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanasi, Silvia, Antonio Ghezzi, Angelo Cavallo, and Andrea Rangone. 2020. Making Sense of the Sharing Economy: A Business Model Innovation Perspective. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 32: 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuotto, V., S. Le Loarne Lemaire, D. Magni, and A. Maalaoui. 2022. Extending Knowledge-Based View: Future Trends of Corporate Social Entrepreneurship to Fight the Gig Economy Challenges. Journal of Business Research 139: 1111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessions, Hudson, Jennifer D. Nahrgang, Manuel J. Vaulont, Raseana Williams, and Amy L. Bartels. 2021. Do the Hustle! Empowerment from Side-Hustles and Its Effects on Full-Time Work Performance. Academy of Management Journal 64: 235–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, Genevieve, and Mark Smith. 2021. Fair’s Fair: Psychological Contracts and Power in Platform Work. International Journal of Human Resource Management 32: 4078–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirapani, Alessandro Niccolò, and Hugh Willmott. 2023. Revisiting Conflict: Neoliberalism at Work in the Gig Economy. Human Relations 76: 53–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traag, V. A., L. Waltman, and N. J. van Eck. 2019. From Louvain to Leiden: Guaranteeing Well-Connected Communities. Scientific Reports 9: 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldkirch, Matthias, Eliane Bucher, Peter Kalum Schou, and Eduard Grünwald. 2021. Controlled by the Algorithm, Coached by the Crowd–How HRM Activities Take Shape on Digital Work Platforms in the Gig Economy. International Journal of Human Resource Management 32: 2643–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Wei, and Ian Thomas MacDonald. 2022. Modeling the Job Quality of ‘Work Relationships’ in China’s Gig Economy. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 60: 855–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, Martin, W. Alec Cram, and Alexander Benlian. 2023. Algorithmic Control and Gig Workers: A Legitimacy Perspective of Uber Drivers. European Journal of Information Systems 32: 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, Adrian, Michael Knoll, Paula K. Mowbray, and Tony Dundon. 2021. New Trajectories in Worker Voice: Integrating and Applying Contemporary Challenges in the Organization of Work. British Journal of Management 32: 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Alex J., Nicholas Martindale, and Vili Lehdonvirta. 2023. Dynamics of Contention in the Gig Economy: Rage against the Platform, Customer or State? New Technology, Work and Employment 38: 330–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Alex J., Vili Lehdonvirta, and Mark Graham. 2018. Workers of the Internet Unite? Online Freelancer Organisation among Remote Gig Economy Workers in Six Asian and African Countries. New Technology, Work and Employment 33: 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Qiongrui (Missy), La Kami T. Baker, and Franz T. Lohrke. 2022. Building and Sustaining Trust in Remote Work by Platform-Dependent Entrepreneurs on Digital Labor Platforms: Toward an Integrative Framework. Journal of Business Research 149: 327–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

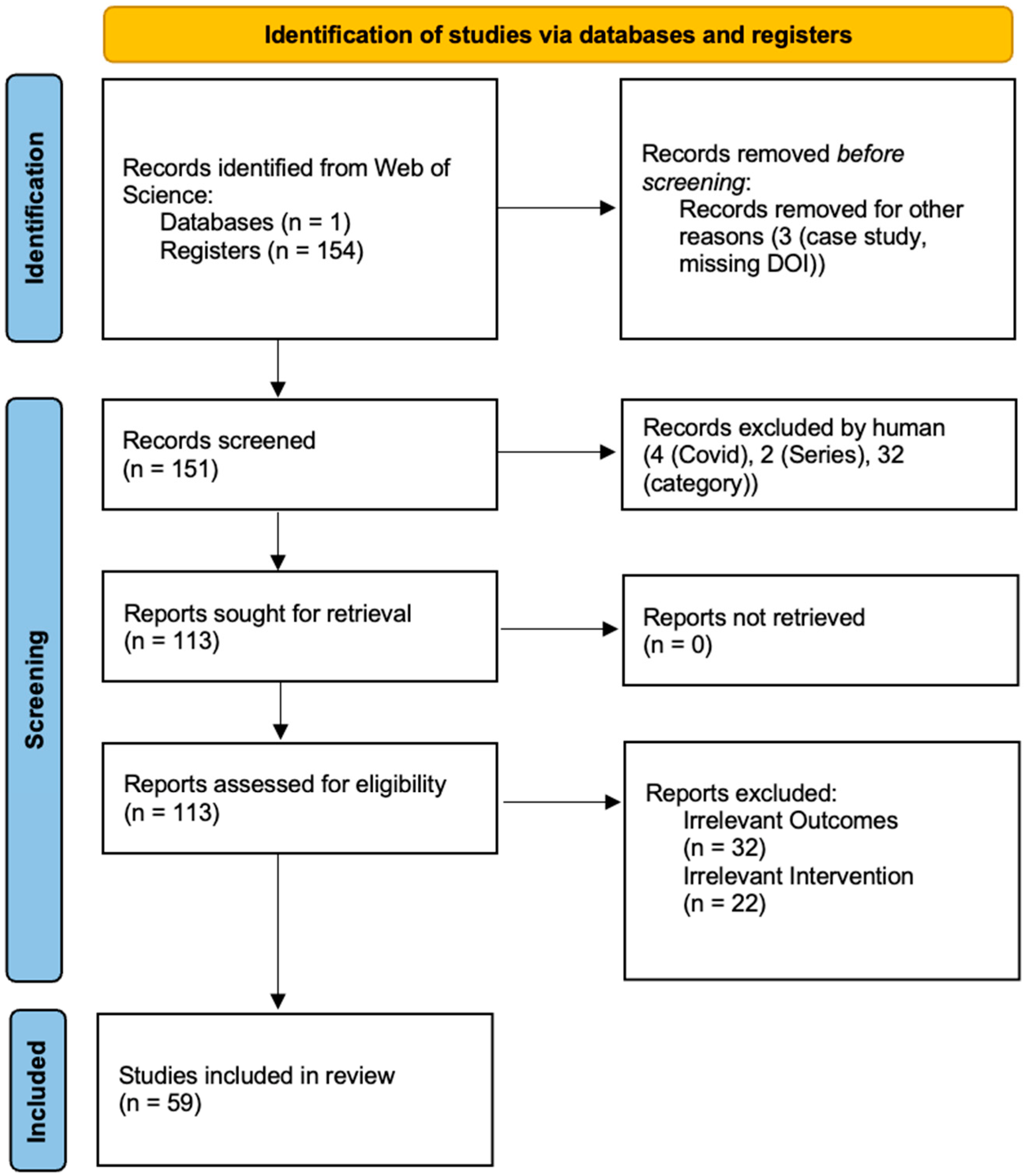

| Stage | Sub-Stage | Criterion | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assembling | Identification | Domain | Management, Business and Business Economics |

| Research questions | What is known about the power dynamics, worker autonomy, and the role of social networks in the gig economy? | ||

| How does algorithmic management impact gig workers’ agency and collective action? | |||

| Where should future research on the gig economy be heading to effectively address power imbalances and enhance worker empowerment through a comprehensive framework? | |||

| Source type | Academic Journals in English | ||

| Source quality | Web of Science (WOS) | ||

| Acquisition | Search mechanism and material acquisition | WOS | |

| Search period | 2009–2023 | ||

| Search keywords | Boolean search | ||

| Total number of articles returned from the search | 154 | ||

| Arranging | Organization | Organizing codes | Bibliometric (category, citation network, citations, and reference) and content analysis (study outcomes and context) |

| Purification | Article type included/excluded | Article outcomes, missing information, citation network impact, WOS category | |

| Total number of articles returned from the purification | 59 | ||

| Assessing | Evaluation | Analysis method | Bibliographic modeling, topic modeling, and article content |

| Agenda proposal method | Gaps’ identification, framework creation, and future research | ||

| Reporting | Reporting | Combination of discussions and chart images |

| Cluster (Color) | Main Themes | Representative Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Yellow | Digital platforms, algorithmic management, power imbalances, worker autonomy, organizational control | Kellogg et al. (2020); Yao et al. (2022); Gegenhuber et al. (2021); Wilkinson et al. (2021) |

| Green | Gig worker behavior, algorithmic control, worker agency, resistance | Wei and MacDonald (2022); Norlander et al. (2021); Petriglieri et al. (2019); Bucher et al. (2021); Waldkirch et al. (2021) |

| Blue | Impact of digital platforms on labor markets, worker experiences, gig economy dynamics | Newlands (2021); Anwar and Graham (2021); Elbanna and Idowu (2022) |

| Purple | Power imbalances, algorithmic control, worker resistance, sharing economy business models, self-leadership, institutional complexities in HRM | Cameron and Rahman (2022); Crayne and Newlin (2023); Sanasi et al. (2020); McDonnell et al. (2021) |

| Topic | Is It Addressed (Focus) in the Current Article? |

|---|---|

| Emerging Trends | |

| Worker Resistance and Collective Agency: Increasing focus on how gig workers use strategies like rating manipulation, forming support networks, and engaging in collective bargaining to counteract platform control. | Yes. We highlight the gig workers’ social networks and how they might use strategies to resist platform control and gain autonomy. |

| Psychological and Emotional Dimensions: Growing recognition of the mental health impacts of gig work, including how workers create “holding environments” for emotional support. | Partially. The article discusses how gig workers manage the emotional and psychological impacts of precarious work by forming “holding environments” or supportive structures to cope with the stresses of gig work. However, more detailed empirical research could be beneficial in examining how these holding environments function and their effectiveness in fostering long-term worker resilience. |

| Technological Adaptation and Skill Development: Exploring how gig workers adapt to the evolving technologies and develop new skills through platform work. | No. |

| Regulatory Responses and Policy Development: Focus on how regions and countries address gig worker conditions through policy and labor law reforms. | No. |

| Potential Literature Gaps | |

| Absence of a Holistic Framework: The literature lacks an integrated framework that connects power dynamics, worker autonomy, and social networks, leaving the interplay between these elements underexplored. | Yes. We aim to fill this gap by developing a comprehensive framework integrating power dynamics, worker autonomy, and social networks. The focus is on creating a holistic approach. |

| Lack of Research on the Positive Outcomes of Algorithmic Management: The current focus is on disempowerment, with limited discussion on how platforms may foster entrepreneurship or skill development. | Partially. We touch on worker resistance but lack emphasis on how algorithmic management could foster entrepreneurship or skills. |

| Long-Term Impact on Well-being and Career Development: Insufficient research on how prolonged gig work affects long-term career trajectories, skill acquisition, and life satisfaction. | Partially. We discuss the psychological impacts but focus less on long-term career trajectories or skill acquisition. |

| Lack of Intersectional Analysis: Limited comprehensive analysis integrating the diverse experiences of gig workers based on gender, race, and socio-economic status into the broader gig economy research. | No. |

| Retirement Plans for Gig Workers: Absence of discussions on how gig workers, especially low-skilled workers, can ensure financial security for retirement. | No. |

| Research Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Q1. What is known about the power dynamics, worker autonomy, and the role of social networks in the gig economy? | The power dynamics in the gig economy are characterized by significant imbalances, where platforms exert control through algorithmic management, often leading to reduced autonomy for workers. However, gig workers form social networks that act as mechanisms of resistance, enhancing collective agency and autonomy. These networks enable the sharing of information, negotiation strategies, and collective actions that counteract the control exerted by platforms and challenge the established power structures. Social networks thus play a critical role in promoting worker empowerment and addressing the power asymmetries in gig work. |

| Q2. How does algorithmic management impact gig workers’ agency and collective action? | Algorithmic management significantly shapes gig workers’ behaviors and psychological experiences by creating an environment of surveillance and control that often limits worker autonomy. Algorithms assign tasks, evaluate performance, and regulate access to work, which can lead to feelings of disempowerment and economic precarity. Psychologically, gig workers may experience stress, frustration, and anxiety due to the unpredictable nature of algorithmic decision making. However, the article highlights that workers are not passive in response to these pressures. Many develop coping mechanisms, such as creating personal “holding environments”—supportive structures that help them manage emotional tensions. Furthermore, workers engage in forms of covert resistance, including data manipulation, rating management, and collective action through social networks. These psychological strategies enable gig workers to reclaim some degree of agency, maintain viable work identities, and foster resilience despite the control exerted by algorithmic management. Collective action, bolstered by shared experiences of algorithmic pressure, allows workers to develop solidarity and challenge the system collectively. Thus, while algorithmic management imposes significant constraints, gig workers use individual and collective psychological and behavioral strategies to navigate and resist these controls. |

| Q3. Where should future research on the gig economy be heading to effectively address power imbalances and enhance worker empowerment through a comprehensive framework? | Future research should explore the long-term effects of gig work on career development and worker well-being, investigate the potential positive aspects of algorithmic management, and delve into how intersectionality affects worker experiences in the gig economy. Additionally, studies should consider how regulatory frameworks can be designed to protect worker rights without exacerbating the informality in the sector. A comprehensive framework that integrates economic, technological, social, and regulatory forces can help develop strategies to empower gig workers more effectively. |

| Forces | Platforms (Algorithmic Management) | Customers | Other Gig Workers (Community) | Regulatory Bodies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Incoming | Platforms drive economic incentives and job availability through algorithmic task assignments and payment structures. | Customers provide financial compensation and demand services. | Collective bargaining and shared resources reduce individual costs. | Regulations and labor laws determine minimum wage and protections. |

| Outgoing | Gig workers’ performance and availability directly influence platform metrics and profitability. | The quality of service and customer satisfaction impact repeat business and tips. | The participation in community efforts can influence overall market rates and conditions. | Workers’ economic struggles drive the advocacy for better policies and benefits. | |

| Technological | Incoming | Platforms use algorithms for surveillance and control, affecting work availability and conditions. | Customer reviews and ratings impact workers’ algorithmic scores and future job opportunities. | Technology facilitates the communication and organization among workers. | Technological regulations impact the development and deployment of gig platforms. |

| Outgoing | Worker data and feedback influence algorithmic adjustments and platform policies | Workers’ adherence to technological tools and communication platforms enhances the customer experience. | Workers contribute to online forums and support networks, enhancing collective knowledge. | Workers’ use of technology can advocate for improved digital labor rights and protections. | |

| Social | Incoming | Platform policies and culture shape workers’ social interactions and norms. | Customer interactions and expectations shape social norms and worker conduct. | Peer support and collective identity strengthen social bonds and resilience. | Social policies and public opinion influence regulatory actions and worker protections. |

| Outgoing | Workers’ social behaviors and compliance affect platform reputation and user trust. | Workers’ professionalism and service quality influence customer perceptions and social feedback. | Workers’ active participation in social movements can drive community cohesion and advocacy. | Workers’ social activism and participation in public discourse drive regulatory change and awareness. | |

| Regulatory | Incoming | Compliance with labor laws and platform regulations impacts job security and conditions. | Consumer protection laws and regulations impact service standards and worker obligations. | The legal recognition of worker organizations enhances collective bargaining power. | Labor regulations and protections define workers’ rights and benefits. |

| Outgoing | Workers’ adherence to and feedback on regulations influence platform adjustments and legal compliance. | Workers’ compliance with regulatory standards ensures customer trust and legal operation. | Workers’ legal actions and collective agreements influence broader industry standards and policies. | Workers’ advocacy and participation in policy development shape future regulations and labor laws. |

| Research Question | Theoretical Framework Components | Explanation of How the Framework Addresses each Question |

|---|---|---|

| Q1. What is currently understood about the power structures, worker autonomy, and the function of social networks within the gig economy? |

|

|

| Q2. How does algorithmic management shape gig workers’ agency and their capacity for collective action? |

|

|

| Q3. Where should future research on the gig economy focus to effectively address power imbalances and promote worker empowerment? |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pilatti, G.R.; Pinheiro, F.L.; Montini, A.A. Systematic Literature Review on Gig Economy: Power Dynamics, Worker Autonomy, and the Role of Social Networks. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100267

Pilatti GR, Pinheiro FL, Montini AA. Systematic Literature Review on Gig Economy: Power Dynamics, Worker Autonomy, and the Role of Social Networks. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(10):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100267

Chicago/Turabian StylePilatti, Gustavo R., Flavio L. Pinheiro, and Alessandra A. Montini. 2024. "Systematic Literature Review on Gig Economy: Power Dynamics, Worker Autonomy, and the Role of Social Networks" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 10: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100267

APA StylePilatti, G. R., Pinheiro, F. L., & Montini, A. A. (2024). Systematic Literature Review on Gig Economy: Power Dynamics, Worker Autonomy, and the Role of Social Networks. Administrative Sciences, 14(10), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100267