Understanding the Dynamics of Board-Executive Director Relationships in Nonprofits: A Qualitative Study of Youth-Serving Nonprofits in Utah

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Duty of Care: Board members must use prudence and informed judgment when making decisions regarding any aspect of the organization;

- Duty of Loyalty: Board members are faithful to the organization they serve and the organization’s best interest. They avoid placing personal interests or others’ interests above the organization’s interests;

- Duty of Obedience: Board members exhibit loyalty to the organization’s mission, bylaws, and policies when making decisions for the nonprofit.

2. Results

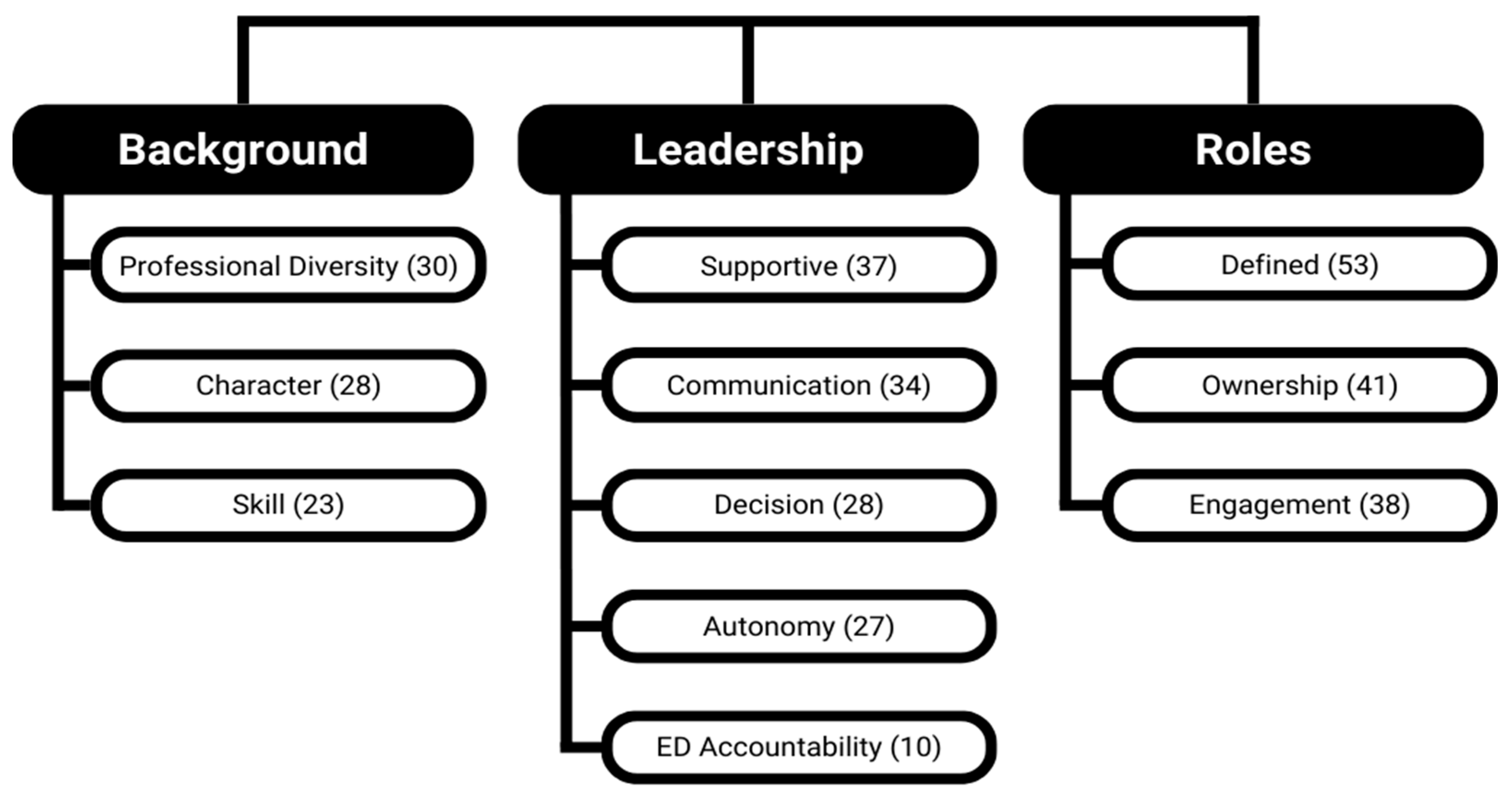

2.1. Theme 1: Background

2.1.1. Professional Diversity

2.1.2. Character

Organization A, Board Chair 1: [She] cares, she’s on top of things, she’s organized, she’s connected.

Organization D, Executive Director 4: She’s very comfortable to talk to, and is very engaged with the mission. … She’s just really supportive and really wants to see the best for the organization and all of the staff.

Organization F, Board Chair 6: That’s one thing that I really admire about [the executive director] is just her drive to continually self-improve so that it can then be put back into [the organization].

2.1.3. Skills

Organization C, Executive Director 3: I think we have a great working relationship, because we communicate really well together. He’s very engaged in the organization and … communication wise he’s just, he’s very direct, very open, very honest, so we can have open honest conversations.

Organization D, Board Chair 4: She’s extremely organized. And she has a system, so when she is working on a particular project, whether it’s our online auction fundraiser or trying to figure out how to evaluate financial transactions throughout the year she’s just very organized.

2.2. Theme 2: Leadership Approach

2.2.1. Supportive

Organization A, Board Chair 1: She’s worked very closely with me, really, I felt kind of handheld into the board. … This is my first board experience so having somebody who wants … wants to communicate and coordinate so closely has been a great positive experience for me.

Organization B, Board Chair 2: I would not be able to run this board without her support and her engagement.

Organization B, Executive Director 2: She’s also really hands-on in terms of her support. We meet every single week. She’s very thoughtful in the way that she helps me to frame my thinking [and] my presentation to the board. She edits things for me. She’s just a really good ally. She’s a really good partner.

Organization D, Executive Director 4: They’re very supportive, lot of words of encouragement and concern for my well-being, which is wonderful. Yeah, they’re very sweet people. I’m really happy to know them.

Organization F, Executive Director 6: You essentially have seven bosses. … If I had to combine them all into one style. I mean, really mostly just supportive. You give us information, you tell us what you need, and we’ll try and help you with the expertise that we have, or- it’s more of a we’re here to help and support you, how can we do that, you tell us how to do that.

2.2.2. Communication

Organization B, Executive Director 2: I would say, the more personal the communication, the better because I just think it’s extremely helpful.

Organization D, Board Chair 4: We really promote a culture of safety and speaking your mind respectfully. You know just keeping communication open.

Organization F, Executive Director 6: We both feel like we can ask hard questions about how the board’s functioning and she can ask hard questions about how the organization is running and trust each other to communicate where we think things can improve on either side and how we can support each other to improve those areas.

2.2.3. Decision-Making

2.2.4. Autonomy

Organization E, Executive Director 5: I personally love the autonomy that I’m allowed as the executive director and that they really listen to what I have. … I love that they respect and appreciate the feedback and the ideas that I have and kind of add to that rather than imposing something. … That’s something I think is really functional about the Board is that there’s a good culture of respect and collaboration and trust, and I think that permeates through every part of the organization and it starts with them.

Organization E, Board Chair 5: I feel like because we have so much trust in [the executive director] that we just check in but we back off. … we talk about what needs to be done, [then] we let him go for it and do it.

2.2.5. ED Accountability

Organization F, Executive Director 6: Most of the board agenda is me reporting to the board and asking for input, and we have discussions around areas that I need recommendations in, or input in, or their help and support with.

Organization D, Executive Director 4: Just like every month when we meet, I type up the meeting report. … It’s like a journal basically, like here’s what I did this month and what the organization does programmatically what we’re doing. And they read it, and ask me questions, and then we’ll move on from there. And if anything is concerning they bring it up.

2.3. Theme 3: Roles

2.3.1. Defined

Organization F, Executive Director 6: My role is to implement and ensure the organization is following the policies, procedures, and the strategic direction that the Board and [I] formulated together. And so it’s to make sure that the organization implements that plan and those policies. And to also help set the vision or direction of the organization, ensure sustainability in the organization, [and] ensure community goodwill and PR for the organization.

Organization C, Executive Director 3: So I feel like the role of the board of directors is to provide guidance to me. And also, at the same time, make sure that I’m doing my job in a satisfactory way. … I think having [a] … board of directors to then help guide and advise you is really important. I use … our board meetings to get ideas, to get energized, [and] to make sure … ideas we’re running with are going in the right direction.

Organization B, Executive Director 2: [The board has] a fiduciary responsibility, both oversight for the budget, as well as a responsibility to ensure that we have the wherewithal and finances, we need to operate

Organization D, Executive Director 4: I think, from what I know and have read with other boards, the other board of directors are much more engaged with fundraising and like finding new prospects. … There’s never really been a clear expectation of who, on the board, whose job that is. You know, that’s kind of like a collective job.

Organization D, Board Chair 4: [The ED’s] role is basically to manage daily operations and that can’t happen without sufficient fundraising as it is being a nonprofit so. I mean she’s the boss, she’s the go-to lady, she basically does the schmoozing with the donors, she makes sure that they are sent notes of appreciation and kept in the loop with our financial reports and things that are happening [in the organization].

2.3.2. Ownership

Organization F, Board Chair 6: I think that it’s more her [ED] responsibility with … board support, so I would say something like 80% her and 20% of the board.

Organization F Executive Director 6: If you ask the IRS it’s the board. … If you’re talking about the day-to-day delivery of services and ensuring that our programs are strong, that’s ultimately my responsibility.

Organization E, Board Chair 5: I feel like the board plays its role, and I think that there’s important things that we do. … But I really feel like [the executive director has] got this and he really is pretty amazing. So in this organization, I would say our executive director is … our key player.

Organization A, Executive Director 1: I would say me, I would take … that burden on myself.

Organization A, Board Chair 1: The managing director is, is primarily responsible for the success of the organization, but the board is a safety net when things aren’t going well. The board steps in, the board helps out, the board may have to hire a different executive director.

Organization D, Executive Director 4: Accountable to the success on the day-to-day, month-to-month? Me. Accountable overall? Definitely, the board. Because if I’m not doing my job they’re gonna fire me.

2.3.3. Engagement

Organization D, Board Chair 4: It is a volunteer board, and so we do get board members from time to time that just are really too busy to be giving the time they’ve committed. And they probably have a lot to offer, but aren’t present either mentally or physically.

Organization E, Executive Director 5: I would define an engaged board as they feel empowered enough by engaging with our programming and talking with me … to bring ideas to the table. And that they feel like they can add value to conundrums that we have or issues that we’re up against and where I love and what I consider a really engaged board is that they’re with it enough to know what’s going on within the organization that they can add ideas. Not only ideas but then also resources or connections that help us to accomplish things in a better way or things we couldn’t do before.

Organization, F Executive Director 6: I think we have a really strong board other than … for an hour and a half a month, how much knowledge do you really have about what the organization needs? And that’s my job to communicate that, but it is sometimes a little bit difficult.

2.3.4. Limitations

3. Methods

3.1. Worldview, Guiding Frameworks, and Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Ethical Considerations

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Measures

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Background

4.2. Leadership Approach and Roles

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Preliminary Surveys

- Preliminary Survey Questions—Board Chair

- What is your name?

- What gender do you identify with?

- What is your age?

- What is your mobile phone number?

- What is your preferred email address?

- What is your profession/vocation?

- What organization are you the board chair of?

- How long have you served as the board chair of this organization?

- How many volunteers are active members of the board?

- Does your organization have a board charter and/or board member agreement?

- Does your organization have a detailed job description for the executive director and board chair?

- Has the board conducted a formal performance review of the executive director and documented it within the last year?

- Has the board conducted a self-assessment within the last two years?

- Does the executive director have an employment contract in writing?

- What is the board’s overall satisfaction level concerning its working relationship with the executive director?

- Likert scale (1 Extremely Dissatisfied; 2 Dissatisfied; 3 Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied; 4 Satisfied; 5 Extremely Satisfied)

- What is your overall satisfaction level concerning your working relationship with the executive director?

- Likert scale (1 Extremely Dissatisfied; 2 Dissatisfied; 3 Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied; 4 Satisfied; 5 Extremely Satisfied)

- Preliminary Survey Questions—Executive Director

- What is your name?

- What gender do you identify with?

- What is your age?

- What is your mobile phone number?

- What is your preferred email address?

- What organization are you the executive director of?

- How long have you been the executive director of this organization?

- How many paid employees work for your organization?

- Are you an ex officio or voting member of the board?

- Does your organization have a board charter and/or board member agreement?

- Does your organization have a detailed job description for the executive director and board chair?

- Has the board conducted a performance review of you and documented it within the last year?

- Has the board conducted a self-assessment within the last two years?

- Do you have an employment contract in writing?

- What is your overall satisfaction level concerning your working relationship with the board of directors?

- Likert scale (1 Extremely Dissatisfied; 2 Dissatisfied; 3 Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied; 4 Satisfied; 5 Extremely Satisfied)

- What is your overall satisfaction level concerning your working relationship with the board chair?

- Likert scale (1 Extremely Dissatisfied; 2 Dissatisfied; 3 Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied; 4 Satisfied; 5 Extremely Satisfied)

Appendix B. Interview Guides

- Interview Guide Questions—Board Chair

- What is the role of the board of directors?

- What is the executive director’s role?

- Who is most accountable for the success of the organization, the executive director or the board of directors? Why?

- What do you feel are the greatest strengths the board of directors bring to your organization? The greatest weaknesses?

- What do you feel are the greatest strengths the executive director brings to your organization? The greatest weaknesses?

- Do you prefer to work alone or work in a team? Why?

- If any, what are your communication preferences when it comes to collaboration with the executive director?

- If the executive director made decisions for the organization without consulting you or the board, how would you react?

- Describe the types of decisions the board would be comfortable making without consulting the executive director.

- What types of decisions warrant the executive director’s input or approval?

- If the board disagrees with a decision made by the executive director, how does it handle it?

- What kind of support does the executive provide board members in fulfilling their legal duties?

- How crucial is the executive director to your success as a board chair? Why?

- Describe the management style of the board of directors as it relates to the work of the executive director.

- In the survey, you indicated that overall the board is (extremely dissatisfied, dissatisfied, neutral, satisfied, or extremely satisfied) concerning its working relationship with the executive director. Describe why the board is (extremely dissatisfied, dissatisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, satisfied, or extremely satisfied) with this relationship.

- In the survey, you indicated that overall you are (extremely dissatisfied, dissatisfied, neutral, satisfied, or extremely satisfied) concerning your relationship with the executive director. Describe why you are (extremely dissatisfied, dissatisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, satisfied, or extremely satisfied) with this relationship.

- Interview Guide Questions—Executive Director

- What is your role as the executive director?

- What is the role of the board of directors?

- Who is most accountable for the success of the organization, the board or, you, the executive director? Why?

- What do you feel are the greatest strengths you bring to your organization as an executive director? The greatest weaknesses?

- What do you feel are the greatest strengths the board brings to your organization as a whole? The greatest weaknesses?

- Do you prefer to work alone or work in a team? Why?

- If any, what are your communication preferences when it comes to collaboration with the board?

- If the board made decisions for the organization without consulting you, how would you react?

- Describe the types of decisions you would be comfortable making without consulting the board or board chair.

- What types of decisions warrant the board’s or board chair’s input or approval?

- If you disagree with a decision made by the board, how do you handle it?

- What is your role in planning and participating in board meetings?

- How crucial is the board chair to your success as an executive director? Why?

- Describe the management style of the board of directors as it relates to your work as the executive director.

- In the survey, you indicated that overall you are (extremely dissatisfied, dissatisfied, neutral, satisfied, or extremely satisfied) concerning your working relationship with the board of directors. Describe why you are (extremely dissatisfied, dissatisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, satisfied, or extremely satisfied) with this relationship.

- In the survey, you indicated that overall you are (extremely dissatisfied, dissatisfied, neutral, satisfied, or extremely satisfied) concerning your working relationship with the board chair. Describe why you are (extremely dissatisfied, dissatisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, satisfied, or extremely satisfied) with this relationship.

Appendix C. Code Book

| Themes and Theme Definitions | Associated Codes and Code Definitions |

| Background: Previous experience of a board, board member, board chair, or ED | Professional Diversity: Involves the presence of individuals with diverse professional backgrounds on a board and the extent to which these backgrounds provide valuable support to executives. Character: Refers to an individual’s mental and moral qualities, encompassing their ethical and personal attributes. Skill: Pertains to the practical and applicable skills an individual possesses, reflecting their competence in fulfilling their role. |

| Leadership: How the board and executive function with each other and lead the organization | Supportive: Concerns the board’s involvement and whether it is supportive or unsupportive in regards to the work of the ED. Communication: Encompasses the style, frequency, and communication preferences between the ED and the board. Decision-making: Encompasses the processes and methods by which the board and ED make organizational decisions. Autonomy: Describes the degree of freedom granted to the ED to accomplish their work and the level of trust the board places in the ED. ED Accountability: Involves how accountable the ED is to the board, including how they take responsibility for their actions and how actively they engage in board interactions and task initiation. |

| Roles: What they do and attitudes about their role | Defined: Relates to the clarity of role definitions between the board and ED. Ownership: Addresses whether the individuals in their respective roles take ownership of the outcomes resulting from their efforts and whether they acknowledge responsibility for their contributions. Engagement: Reflects how committed and active individuals are in fulfilling their respective roles. |

| 1 | It is important to note that this article discusses mainstream 501(c)(3) nonprofits. Smaller, grassroots, or differently structured nonprofits may not follow this governance model. |

References

- Almaney, Adnan. 1974. Communication and the systems theory of organization. Journal of Business Communication 12: 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, Del M., and Sue Carter Kahl. 2021. Founder or flounder: When board and founder relationship impact nonprofit performance. Journal of Public Affairs Education 27: 238–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, Stephen R. 1998. Perfect Nonprofit Boards: Myths, Paradoxes and Paradigms. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- BoardSource. 2021. Leading with Intent: BoardSource Index of Nonprofit Board Practices. Available online: https://leadingwithintent.org/diversity-equity-and-inclusion-findings/ (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Bobowick, Marla, Will Brown, Anne C. Donnelly, Donald Haider, Judith Millesen, Rick Moyers, Una Osili, David Renz, Bill Ryan, Cathy Trower, and et al. 2021. Leading with Intent: Board Source Index of Nonprofit Board Practices. Washington, DC: Leading With Intent. Available online: https://leadingwithintent.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2021-Leading-with-Intent-Report.pdf?hsCtaTracking=60281ff7-cadf-4b2f-b5a0-94ebff5a2c25%7C428c6485-37ba-40f0-a939-aeda82c02f38 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Bradshaw, Patricia. 2009. A contingency approach to nonprofit governance. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 20: 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Building Movement Project. 2022. Trading Glass Ceilings for Glass Cliffs: A Race to Lead Report on Nonprofit Executives of Color. Available online: https://buildingmovement.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Race-to-Lead-ED-CEO-Report-2.8.22.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Building Movement Project. 2024. The Push and Pull: Declining Interest in Nonprofit Leadership. Available online: https://buildingmovement.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/BMP_The-Push-and-Pull-Report_Final.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- Buse, Kathleen, Ruth S. Bernstein, and Diana Bilimoria. 2016. The influence of board diversity, board diversity policies and practices, and board inclusion behaviors on nonprofit governance practices. Journal of Business Ethics 133: 179–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candid. 2020. Can the Executive Director Also Serve on Our Organization’s Board of Directors? Candid Learning. Available online: https://learning.candid.org/resources/knowledge-base/executive-director-on-board/ (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Carver, John. 2006. Boards that Make a Difference: A New Design for Leadership in Nonprofit and Public Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Cornforth, Chris. 2012. Nonprofit governance research: Limitations of the focus on boards and suggestions for new directions. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41: 1116–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., and Cheryl N. Poth. 2018. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W., and Vicki L. Plano Clark. 2004. Principles of qualitative research: Designing a qualitative study. In Office of Qualitative & Mixed Methods Research. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska. [Google Scholar]

- DeCarlo, Matthew. 2018. Scientific Inquiry in Social Work. Minneapolis: Open Textbook Library. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, Peter F. 1990. Lessons for successful nonprofit governance. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 1: 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duta, Andrei. 2011. Nested at the heart: A new approach to nonprofit leadership. Nonprofit World 29: 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fram, Eugene. 2014. Once again! Should a Nonprofit CEO be a Voting Member of the Board of Directors? The Huffington Post. Available online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/eugene-fram/once-again-should-anonpr_b_4408917.html (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Garry, Joan. 2019. Thriving as an executive director. In Nonprofit Management 101: A Complete and Practical Guide for Leaders and Professionals, 2nd ed. Edited by Darian Rodriguez Heyman and Laila Brenner. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Golensky, Martha. 1993. The board-executive relationship in nonprofit organizations: Partnership or power struggle? Nonprofit Management and Leadership 4: 177–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Yvonne D., and Vic Murray. 2012. Perspectives on the leadership of chairs of nonprofit organization boards of directors: A grounded theory mixed-method study. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 22: 411–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, Monique, and Bonnie N. Kaiser. 2022. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine 292: 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, Robert D. 2016. Chapter six: Executive leadership. In The Jossey-Bass Handbook of Nonprofit Leadership and Management, 4th ed. Edited by David O. Renz. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 167–87. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Robert D., and David O. Renz. 2000. Board practices of especially effective and less effective local nonprofit organizations. The American Review of Public Administration 30: 146–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, Robert D., David O. Renz, and Richard D. Heimovics. 1996. Board practices and board effectiveness in local nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 7: 373–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiland, Mary. 2008. The board chair-executive director relationship: Dynamics that create value for nonprofit organizations. Journal for Nonprofit Management 12: 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Sector. 2023. 2022 Annual Report. Available online: https://independentsector.org/resource/2022-annual-report/ (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Inglis, Sue, and Shirley Cleave. 2006. A scale to assess board member motivations in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 17: 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, Urs P., and Florian Rehli. 2012. Cooperative power relations between nonprofit board chairs and executive directors. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 23: 219–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskyte, Kristina. 2018. Board attributes and processes, board effectiveness, and organizational innovation: Evidence from nonprofit organizations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 29: 1098–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Johnny S., and Kristin Whitehill Bolton. 2013. Strengths perspective. Encyclopedia of Social Work. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, Jodie B., and Dwight V. Denison. 2008. Fostering effective relationships among nonprofit boards and executive directors. Journal for Nonprofit Management 23: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, Dyana P., and Mirae Kim. 2020. A board coaching framework for effective nonprofit governance: Staff support, board knowledge, and board effectiveness. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance 44: 452–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, Melissa A. 2019. Betwixt and between the board chair and executive director: Dyadic leadership role perceptions within nonprofit organizations. Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership 9: 281–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Duncan J., and Robert L. Fischer. 2023. Exploring data use in nonprofit organizations. Evaluation and Program Planning 97: 102197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, Matthew B., A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldana. 2019. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Stevens, Katrina, and Kevin D. Ward. 2019. Nonprofit board members’ reasons to join and continue serving on a volunteer board of directors. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 31: 61–83. [Google Scholar]

- National Council of Nonprofits. 2024. Self-Assessments for Nonprofit Boards. Available online: https://www.councilofnonprofits.org/running-nonprofit/governance-leadership/self-assessments-nonprofit-boards (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Nicholson, Gavin J., and Geoffrey C. Kiel. 2004. A framework for diagnosing board effectiveness. Corporate Governance: An International Review 12: 442–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olinske, Jaime L., and Chan M. Hellman. 2016. Leadership in the human service nonprofit organization: The influence of the board of directors on executive director well-being and burnout. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance 41: 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orland-Barak, Lily, and Ronit Hasin. 2010. Exemplary mentors’ perspectives towards mentoring across mentoring contexts: Lessons from collective case studies. Teaching and Teacher Education 26: 427–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrower, Francie, and Melissa M. Stone. 2006. Governance: Research trends, gaps, and future prospects. In The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, 2nd ed. Edited by Walter W. Powell and Richard Steinberg. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 612–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrower, Francie, and Melissa M. Stone. 2010. Moving governance research forward: A contingency-based framework and data application. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 39: 901–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, David O. 2016. Chapter five: Leadership, governance, and the work of the board. In The Jossey-Bass Handbook of Nonprofit Leadership and Management, 4th ed. Edited by Robert D. Herman. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 127–66. [Google Scholar]

- Renz, David O., William A. Brown, and Fredrik O. Andersson. 2023. The evolution of nonprofit governance research: Reflections, insights, and next steps. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 52 Suppl. S1: 241S–277S. [Google Scholar]

- Selden, Sally C., and Jessica E. Sowa. 2015. Voluntary turnover in nonprofit human service organizations: The impact of high performance work practices. Human Service Organizations Management, Leadership & Governance 39: 182–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherin, Jessica. 2008. Nonprofit Chief Executives and Their Boards of Directors: An Exploration of Individual and Job Characteristics that Contribute to the Quality of the Executive-Board Relationship. Doctoral dissertation, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada; p. 304889795. [Google Scholar]

- Slevin, Eamonn, and David Sines. 2000. Enhancing the truthfulness, consistency and transferability of a qualitative study: Utilising a manifold of approaches. Nurse Researcher (through 2013) 7: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenny, Steven, Janelle M. Brannan, and Grace D. Brannan. 2022. Qualitative Study; Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470395/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Tsui, Ming-sum, Fernando C. H. Cheung, and Zvi D. Gellis. 2004. In search of an optimal model for board–executive relationships in voluntary human service organizations. International Social Work 47: 169–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Vernetta, and Emily Heard. 2019. Board governance. In Nonprofit Management 101: A Complete and Practical Guide for Leaders and Professionals, 2nd ed. Edited by Darian Rodriguez Heyman and Laila Brenner. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 503–23. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, Jayme E. 2021. More than meets the eye: Organizational capacity of nonprofits in the poor, rural South. Journal of Rural Studies 86: 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, Andrew. 2023. How Public Colleges are Partnering with their Communities. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/articles/how-public-colleges-are-partnering-with-their-communities (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Watt, Diane. 2007. On becoming a qualitative researcher: The value of reflexivity. Qualitative Report 12: 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organization | A | B | C | D | E | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Org. Age | 38 | 8 | 20 | 26 | 22 | 35 |

| No. of Employees | 30 | 26 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 71 |

| No. of Board Members | 13 | 12 | 16 | 7 | 13 | 13 |

| Board Charter | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ED/Chair Job Descriptions | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ED Performance Review | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Board Self-Assessment | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| ED Employment Contract | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| ED Paid | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| NTEE Code | Child Abuse, Prevention of (I72) | Child Day Care (P33) | Youth Development Programs (O50) | Youth Violence Prevention (I21) | Youth Development Programs (O50) | Family Violence Shelters (P43) |

| Participant | Gender Identity | Age | Profession/Vocation | Years as BC/ED |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED1 | Female | 31 | - | 4 |

| BC1 | Male | 54 | Database Engineering Manager | 0.33 |

| ED2 | Female | 61 | - | 0.67 |

| BC2 | Female | 57 | Community Volunteer | 1 |

| ED3 | Female | 46 | - | 4.5 |

| BC3 | Male | 62 | Retired | 1.5 |

| ED4 | Female | 28 | - | 0.46 |

| BC4 | Female | 43 | Physician Assistant | 2.42 |

| ED5 | Male | 40 | - | 6 |

| BC5 | Female | 66 | Nurse | 0.08 |

| ED6 | Female | 49 | - | 25 |

| BC6 | Female | 47 | Board President | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Didericksen, J.; Walters, J.E.; Wallis, D. Understanding the Dynamics of Board-Executive Director Relationships in Nonprofits: A Qualitative Study of Youth-Serving Nonprofits in Utah. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100252

Didericksen J, Walters JE, Wallis D. Understanding the Dynamics of Board-Executive Director Relationships in Nonprofits: A Qualitative Study of Youth-Serving Nonprofits in Utah. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(10):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100252

Chicago/Turabian StyleDidericksen, Jaxon, Jayme E. Walters, and Dorothy Wallis. 2024. "Understanding the Dynamics of Board-Executive Director Relationships in Nonprofits: A Qualitative Study of Youth-Serving Nonprofits in Utah" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 10: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100252

APA StyleDidericksen, J., Walters, J. E., & Wallis, D. (2024). Understanding the Dynamics of Board-Executive Director Relationships in Nonprofits: A Qualitative Study of Youth-Serving Nonprofits in Utah. Administrative Sciences, 14(10), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14100252