Abstract

The burgeoning tourism and hospitality industry is plagued by numerous challenges that pose significant hurdles to its long-term success and sustainability. These challenges encompass a range of factors, including fierce competitive convergence, rapid obsolescence of innovative strategies, and the relentless pursuit of ever-greater competitiveness in the marketplace. In such a service-oriented industry, where customer satisfaction is the sine qua non of success, the role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in shaping consumer attitudes and behavior cannot be overstated. Despite this, the empirical evidence on the impact of CSR on brand advocacy behavior among hospitality consumers (BADB) remains somewhat underdeveloped and incomplete. In light of this knowledge gap, the basic objective of our study is to examine the complex interplay between CSR and BADB in the context of a developing country’s hospitality sector. The authors place a particular emphasis on the mediating role of consumer emotions and the moderating influence of altruistic values (ALVS) in shaping this relationship. Through rigorous empirical analysis, the authors demonstrate that CSR positively and significantly impacts BADB, with consumer engagement (CENG) serving as a crucial mediating variable that facilitates this relationship. These findings have significant theoretical and practical implications for the tourism and hospitality industry. Specifically, the authors show that the judicious deployment of CSR initiatives in a hospitality context can foster a positive behavioral psychology among consumers and, in turn, enhance their advocacy intentions towards the brand. This underscores the importance of carefully crafted CSR strategies to secure a competitive advantage in this dynamic and rapidly evolving sector.

1. Introduction

Globalization, technological changes, and dynamic business environments have led to a shifting competitive landscape in all sectors. Businesses face various challenges, including market complexity (Turoń 2022), shortened product life cycles, stiff competition (Mendon et al. 2019), changing consumer preferences (Boneva 2018), and pressures from stakeholders (Zhang and Zhu 2019; Nguyen and Adomako 2022). In response, organizations are continuously seeking ways to remain competitive and stay alive, with an increasing focus on the role of consumers in organizational success (Priem et al. 2018; Mostaghel and Chirumalla 2021). A strong consumer-brand relationship can provide a real-time differentiation opportunity for brands to stand out from competitors. The literature suggests a variety of theoretical and empirical models to explain how organizations and their consumers interact. For example, organizations employ different strategic options to influence consumer attitudes and behaviors, including loyalty intentions (Hwang and Choi 2020; Ozdemir et al. 2020), satisfaction (Ahrholdt et al. 2019), and purchase preferences (Lăzăroiu et al. 2020).

Recently, the importance of brand advocacy behavior (BADB) as a significant communicative behavior of consumers has been emphasized in the literature. BADB refers to consumers promoting and protecting a brand among their peers and social circles (Cross and Smith 1995), which is crucial from both psychological and competitive standpoints. Studies show that individuals rely on personal sources of information, such as referrals and word of mouth, before making purchase decisions (Big Commerce 2022; McCaskill 2015; Leonard 2022). A recent empirical survey by Nielsen indicates that almost 92% of consumers worldwide prefer personal sources of information (for example, referrals and word of mouth) over all other advertising communications (Buyapowa 2022). BADB is especially relevant to service industries, where consumers cannot test or experience services beforehand (Walz and Celuch 2010), and personal sources of information become more critical. Moreover, human dependence in the service sector makes delivering a consistent consumer experience challenging, making the role of a personal source of information (for example, advocacy) even more important (Sweeney et al. 2020). Being advocated by consumers provides a real-time competitive advantage to service providers, as supported by previous studies. This argument also prevails in the studies of Bilro et al. (2019) and Kumar and Kaushik (2020).

In the literature, it is extensively emphasized that consumers are critical to the success of a business. However, capturing consumers’ attention is challenging due to the complexity of human behavior and psychology influenced by a variety of factors (Kim and Ammeter 2018; Taufique and Vaithianathan 2018; Ramya and Ali 2016). A literature review indicates that there are two main factors that affect consumer behavior in an organizational setting: organizational factors (Wang and Chen 2019; Wiederhold and Martinez 2018) and personal factors (Nguyen et al. 2019; Gifford and Nilsson 2014). Consumer behavior is significantly influenced by organizational factors, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) engagement (Zhang et al. 2021; Gupta et al. 2021a, 2021b).

Tourism, a multifarious sector, has embraced CSR as a keystone of its operations. This conceptual pillar, buttressing the foundation of industry strategies, shines a spotlight on environmental conservation, equitable employment practices, and the prosperity of local communities. International tourism behemoths, keenly aware of their formidable influence, wield it conscientiously to address these pressing concerns (Lund-Durlacher 2015). Fathoming the complexities of an interconnected world, tourism companies take different initiatives to embody their CSR ethos. They recognize that the environment, a fragile and finite resource, demands their utmost care. Consequently, they tend to employ eco-friendly alternatives, curbing energy consumption, reducing waste, and embracing green technologies that coexist harmoniously with nature’s bounty.

The genesis of responsible tourism dates back to 2002, when Cape Town played host to the World Summit on Sustainable Development. During this seminal event, the foundational principles of this paradigmatic shift were crystallized, giving rise to the importance of the Cape Town Declaration. Fast forward to 2007, and the World Travel Market ratified this transformative manifesto, heralding a new era of global consciousness and accountability (Harold 2015). At its core, responsible tourism is a multifarious construct, encompassing a panoply of interrelated objectives. Central to this ethos is the imperative of creating habitats that are both hospitable to residents and visitors alike. To achieve this, tourism stakeholders from all walks of life must come together, pooling their resources and talents to foster a sustainable, equitable ecosystem (Cape Town Declaration 2002). Indeed, the tenets of responsible tourism demand that all participants—operators, hoteliers, governments, locals, and tourists—assume a proactive role in effecting meaningful change. This multifaceted approach requires diligent action, innovative solutions, and unflagging commitment, transcending mere lip service and facile gestures.

When it comes to tourism and hospitality, CSR encapsulates a holistic approach. It necessitates that businesses operating in this sector adopt conscientious, forward-thinking practices. These ventures must be mindful of the social and environmental repercussions of their actions, striving to weave them seamlessly into their organizational identity, objectives, and daily proceedings (Madanaguli et al. 2022). Tourism and hospitality enterprises must strike an elusive balance between stakeholder appeasement and societal legitimacy, ensuring that their pursuits are sustainable and ethically sound. Not only does this dynamic equilibrium safeguard their long-term financial viability, but it also fosters goodwill and strengthens the social fabric of the communities they serve. CSR in tourism takes on a multifaceted role. The delicate interplay between human needs and environmental stewardship culminates in an array of challenges and triumphs. For instance, a responsible tour operator might grapple with the conundrum of exhibiting a region’s natural beauty without contributing to its degradation, or they might seek to promote local cultures and traditions without succumbing to the pitfalls of commodification (Lund-Durlacher 2015). Undoubtedly, cultivating a responsible tourism ecosystem is very important. Implementing CSR in tourism is tantamount to acknowledging that the industry’s actions reverberate far beyond their immediate purview. This acknowledgment translates into a steadfast commitment to foster equitable, sustainable growth. For all its intricacies, the pursuit of CSR in tourism is indelible evidence to the power of progress when underpinned by a collective sense of responsibility and a shared vision for a brighter, more inclusive future.

In the present-day panorama of CSR, a dynamic approach prevails. No longer relegated to the periphery, stakeholders (for example, consumers) emerge as active collaborators, joining forces to bring about meaningful change. They transition from mere recipients to instrumental partners, shaping and executing CSR strategies with unwavering determination (Okazaki et al. 2020). As the zeitgeist shifts, so too do consumer proclivities. An emerging penchant for ethically grounded businesses burgeons, propelling the discerning masses to seek out companies that prioritize social causes. The undercurrents of this transformation are undeniably complex, reflecting a collective effort for a more equitable, sustainable world. Although consumers primarily pursue products and services that cater to their fundamental desires, the allure of social initiatives cannot be understated (Becker-Olsen et al. 2006). Indeed, businesses that harness the potential of CSR strategies may reap the rewards of a competitive edge, bolstering their standing in an increasingly crowded marketplace.

Although CSR has been acknowledged as an important organizational enabler in shaping the behavior of consumers, a recent literature review reveals that previous research on CSR and consumer behavior has mostly focused on consumer loyalty (Fernández-Ferrín et al. 2021; Rivera et al. 2019; Ahmad et al. 2021d) and purchase intentions (Gupta et al. 2021b; Sharma et al. 2018), which are critical for any business. However, this neglects the role of CSR in influencing brand advocacy behavior (BADB), which is highly valuable from both competitive and psychological standpoints. Consumers who act as advocates can benefit a brand they love more than loyal or high-purchase-likelihood consumers (Lowenstein 2011; Natalie 2018).

The existing literature emphasizes the crucial role of CSR in determining various consumer outcomes, but it is incomplete without considering the impact of human emotions (Williams 2014; Calvo-Porral et al. 2018; He and Hu 2022). In studies linking CSR to individual outcomes, scholars have proposed a variety of mediating variables, including emotion, which has been found to be particularly important in influencing advocacy intentions (Dick and Basu 1994; Martin et al. 2008). In light of the recent focus on emotional factors as an outcome of CSR, consumer engagement (CENG) is introduced as a mediator in this study between CSR and BADB (Maher and Zohra 2017; Godefroit-Winkel et al. 2022). Examining the mediating function of CENG in a CSR framework can highlight its influence on BADB. Therefore, it will be interesting to see how CENG, as a mediator, explains BADB in a CSR framework.

Behavioral scientists emphasize the importance of human values in shaping behavior (Torres and Allen 2009; Nikolinakou and Phua 2020). Values are trans-situational (Schwartz 1992) but require a specific context to guide a particular behavior. A relationship between CSR and BADB through CENG may be moderated by altruistic values (ALVS). Since values provide only general guidelines for behavior formation, studying their indirect role is important. This view can also be seen in the studies of Zasuwa (2016) and Marbach et al. (2019). Improving consumers’ ALVS in the context of CSR is expected to moderate the proposed relationship.

This study aims to address critical knowledge gaps in the existing literature by enriching the understanding of the CSR-consumer behavior management relationship from an advocacy perspective. Firstly, the relationship between CSR and BADB has, with rare exceptions, been underexplored despite consumers’ ability to enhance a brand’s reputation (Castro-González et al. 2019). Most CSR scholars have focused on its impact on consumer loyalty and purchase preferences instead.

Secondly, this study is among the few that emphasize human emotions as part of a CSR strategy. While some studies have discussed the role of emotions in behavior from a behavioral perspective (Patwardhan et al. 2020; Guo et al. 2020), many CSR scholars have relied on rational models to understand consumer behavior (Skawińska 2019; Boccia et al. 2019). However, recent CSR scholars have criticized the limited ability of rational models to explain human behavior and propose emotional models as a better alternative (Kraus et al. 2022; Xie et al. 2019). As a means of addressing this gap, the authors examine how consumer emotions, such as CENG, play a role in explaining BADB within the context of CSR.

Lastly, by examining CSR and consumer behavior from a developing country’s perspective, specifically Pakistan, this study hopes to advance the fields of CSR and consumer behavior. Developed countries have conducted most of the previous studies in this area (Cho et al. 2014; Verbeeten et al. 2016; Kudłak 2020), which may not fully reflect CSR’s cultural and context-specific nature. In light of the fact that CSR is a culturally and contextually specific concept (Zou et al. 2021), the context of developing countries cannot be compared with that of developed countries as developed and developing countries differ from each other. Hence, there is a need to conduct separate studies from the standpoint of CSR in the context of developing countries.

This study examines the hypothesized relationships in Pakistan’s tourism and hospitality sector, specifically in the hospitality sector. Several factors led us to choose this sector, including the problem of competitive convergence due to standardized service delivery and short-lived innovations. Since competitors can easily imitate physical outlays and service delivery patterns, hotels have a hard time establishing a solid competitive base in this environment. Additionally, isomorphism in physical outlay and service delivery further complicates the challenge of retaining existing consumers for a long time (Lemy et al. 2019).

A further challenge lies in the shift in consumers’ purchase decision criteria. Modern consumers are less responsive to mass marketing campaigns (Nielson 2007) and prefer personal sources of information over organization-generated sources (Murray 1991; Michael 2022; Klein et al. 2016). In a service context, consumer endorsements as brand advocates have been found to influence other consumers’ purchase decisions significantly (Sweeney et al. 2020). Therefore, the authors propose that consumers as brand advocates in response to CSR can provide a socially responsible organization with a stable competitive advantage and help it outperform its competitors.

1.1. Literature

1.1.1. Theoretical Roots

In this study, various hypotheses are posed and supported using stewardship theory. Stewardship theory originated from the influential work of Donaldson and Davis (1991), who argued that every individual is responsible for others and should act as a steward. In an organizational context, this theory posits that a corporation’s ultimate goal should not be limited to economic efficiency and financial gain. Instead, it should also benefit all stakeholders, including the environment, the community, consumers, employees, and humanity (Karns 2011). The central tenet of this theory is that businesses should exist to serve rather than solely focusing on maximizing profits (Davis et al. 1997b). However, for an ethical organization to embrace the “serve for others” philosophy, it must also have strong financial health. Thus, a stewardship-oriented organization takes responsibility for caring for all stakeholders while actively striving to foster the economic efficiency of shareholders as a steward. In this way, the theory promotes the efficient utilization of different resources while collaborating with other stakeholders (such as consumers) to achieve better organizational outcomes (Contrafatto 2014).

In this regard, the field of CSR has largely been dominated by a stakeholder perspective. Although stakeholder theory was largely used in the previous CSR studies, as behavioral scientists found it suitable to explain different individual behaviors from the perspective of CSR (Lee et al. 2013; Albasu and Nyameh 2017; Friedman and Miles 2006). However, some recent studies cast doubt on the appropriateness of this theory to cover the broad spectrum of CSR (Oliver 2017; Filipovic et al. 2010). Stakeholder theory sees CSR from an instrumental perspective, which is narrow in scope as it assumes the social responsibility of a business only for the close stakeholders. In this vein, it is argued here that a better business case for CSR would be the one in which a business assumes social responsibility not only for the close stakeholders but also considers the other stakeholders under the umbrella of CSR. In this aspect, stewardship theory may be well placed to cover the broad spectrum of CSR as stewardship theory employs a normative viewpoint for stakeholders where the management of an organization acts as a responsible steward and works to benefit all stakeholders (Davis et al. 1997a). Additionally, stewardship theory assumes that the management of a particular enterprise is expected to assume a sense of responsibility and ownership of all organizational resources and should act in a way to fosters the wellbeing of not only the shareholders but also all stakeholders (Donaldson and Davis 1991). In contrast, the prime focus of stakeholder theory is instrumental, which means an organization seeks to maximize its instrumental outcomes, for example, financial performance through stakeholder management (Hillman and Keim 2001). To this end, some recent CSR scholars have argued in the favor of stewardship theory compared to stakeholder theory. For instance, Murtaza et al. (2021) suggested that stewardship theory offers a normative view of CSR which is based on the assumption that the organization should focus on the benefit of all stakeholders rather than assuming an instrumental approach to maximize the shareholders’ wealth. The scholars such as Oliver (2017) have also stressed the importance of stewardship theory compared to stakeholder theory by arguing that stewardship theory offers a more holistic view of CSR that focuses on the larger interest of all stakeholders including those who are not directly related to an organization. Therefore, the authors suggest the stewardship theory is a good alternate to stakeholder theory to cover the broader spectrum of CSR because this theory assumes a normative approach for the betterment of all stakeholders.

There are several similarities between CSR and stewardship theory. For example, an organization that adopts a CSR approach goes beyond its formal boundaries to benefit society and the environment as a whole. Furthermore, an ethical organization following CSR philosophy aims to utilize societal resources with minimal or no negative impact on the natural environment. Interestingly, stewardship theory also advocates for this same concern in organizational management. Specifically, within the marketing and management literature, the concept of product stewardship is discussed (Jensen and Remmen 2017). This literature outlines two key approaches to product stewardship. The first is the life cycle thinking approach. This suggests that products and services have social, ethical, and environmental implications that should be managed from manufacturing to disposal. The second approach emphasizes the concept of shared responsibility, which posits that not only do organizations have a social responsibility to society, but other stakeholders, including consumers, must also support ethical organizations in achieving their social objectives (Oliver 2017). CSR and BADB must therefore be examined through the lens of stewardship theory. As noted earlier in this study, compared to stakeholder theory (which assumes an instrumental approach for stakeholders), stewardship theory assumes a more comprehensive responsibility (a normative approach for stakeholders) to benefit all stakeholders, including those for whom the organization has no ownership. This may be why some behavioral scientists have sought to explain consumer behavior from a stewardship theory perspective (Boateng et al. 2022; Barrage et al. 2020).

1.1.2. Hypotheses Development

CSR and Advocacy Behavior Relationship

CSR is an organization’s sense of responsibility towards the community and biosphere. According to Carroll (1991), CSR is the totality of an organization’s obligation to all stakeholders, including legal, economic, ethical, and discretionary actions to benefit all stakeholders. He referred to legal obligation as a company’s responsibility to observe the rules and regulations of a country/state in which a business operates. Similarly, economic obligation means an organization should be profitable. Ethical obligation relates to the ethical conduct of a business to do what is ethically right. Lastly, the discretionary obligation of a corporation means it should contribute positively towards the wellbeing of all stakeholders, including the community and biosphere.

The existing body of knowledge indicates that contemporary consumers show great respect for the ethical conduct of a socially responsible organization (Ahmad et al. 2021b, 2021d, 2021f; Sun et al. 2020). It has been suggested that when organizations promote their commitment to CSR, it can create a positive attitude among consumers toward the brand, leading to increased loyalty and advocacy (Ahmad et al. 2022b) Additionally, studies have shown that CSR can increase the likelihood of purchase preferences (Bianchi et al. 2019) and consumer loyalty intentions (Zhang 2022). Consumers, as stakeholders, evaluate organizations’ CSR activities positively and reward them through social exchange processes when organizations engage in CSR activities (Farooq et al. 2014; Srivastava and Singh 2021). An ethical organization’s discretionary behavior under the umbrella of CSR fosters a social connection between consumers and the organization. Marin et al. (2009) suggested that consumers tend to admire the socially responsible engagement of an enterprise. Building on this, Karaosmanoglu et al. (2016) noted that an enterprise’s social behavior encourages consumers to think beyond economic benefits and engage in various extra roles.

In specific, when consumers are satisfied with a particular brand, they are expected to share their positive brand experience with others in their social circles (Khoo 2020). In this respect, a growing body of literature has recently argued that a brand’s socially responsible conduct increases consumers’ advocacy intentions (Mahmood et al. 2021; Ogunmokun and Timur 2022; Shah and Khan 2021). One possible explanation for why CSR influences the advocacy intentions of consumers lies in the fact that the socially responsible behavior of an ethical organization creates a positive brand image in the minds of consumers (Latif et al. 2020). In response, consumers are expected to show a positive association with the brand and perceive it as an ethical brand, increasing their advocacy intentions (Lee 2019). Another way CSR influences BADB is in the emotional association consumers build with a particular brand due to its socially responsible commitment to the larger benefit of all stakeholders (Hur et al. 2020). This emotional connection can lead consumers to an increased level of loyalty and advocacy intentions (Coelho et al. 2019). Luo and Bhattacharya (2006) posited that consumers were more likely to show advocacy intentions for a socially responsible brand. A similar finding can be extracted from the work by Sen and Bhattacharya (2001). Similarly, Limbu et al. (2020) found that a hospital’s CSR activities can boost patients’ advocacy behavior.

In the context of the hospitality sector, adopting CSR practices and applying stewardship theory can lead to positive outcomes for both the organization and consumers. Organizations that focus on CSR practices, such as sustainability initiatives, ethical supply chain management, and environmentally-friendly operations, will send a positive message to consumers that they care about their well-being. This can lead to increased loyalty and trust among customers and a better overall brand image. Additionally, applying stewardship theory, which emphasizes that organizations should serve the interests of their stakeholders, can lead to improved customer experiences, increased customer satisfaction, and increased profitability. Moreover, when a hotel organization is perceived to be acting as a responsible steward of resources, such as implementing sustainable practices, supporting the local community, and engaging in ethical business practices, it can create a competitive advantage by attracting consumers who are more likely to support and stay loyal to the organization. Thus, CSR and stewardship theory can be used to positively impact consumer behavior and organizational outcomes in the hospitality sector. It is, therefore, possible to propose a positive link between CSR and BADB. Therefore:

H1:

The advocacy behavior of consumers towards a brand is positively influenced by CSR.

CSR, Engagement, and Advocacy Behavior Relationship

The existing body of literature indicates that while engagement involves behavior, it is usually considered an emotional state of individuals as it is mostly driven by an individual’s feelings and attitude (Saks 2006). From a consumer perspective, the literature suggests that CENG is a multi-faceted variable involving human cognitions and emotions (Patterson et al. 2006). While CENG may involve consumers’ behavioral intentions, CENG is often treated as an emotional state of consumers (Hollebeek et al. 2019). In this respect, Van Doorn et al. (2010) indicated that engaged consumers are emotionally connected with a particular brand/product/service. Moreover, such consumers often seek out different information about a brand they love and share their opinions about the brand with others and participate in different brand-related activities. Pantano and Viassone (2015) posited that CENG is an emotional state characterized by a deep level of identification, involvement, and attachment of consumers to a certain brand. They further stated that CENG many involve both negative and positive emotions of consumers. Kumar and Pansari (2016) were of the opinion that CENG is an emotional aspect of consumer psychology arising from a consumer’s interaction with a brand/product/service. Hollebeek et al. (2019) specified CENG as an emotional connection in the consumer-brand relationship. In an educational context, Fredricks et al. (2004) mentioned that student engagement is an emotional state of students that encompasses emotional feelings of the student towards their school.

More recently, researchers have found that consumers engage with certain brands in an organizational setting due to the brand’s social responsibility and commitment to society and the environment (Pradhan 2018). This suggests that CENG is not solely based on the specific contexts or specialties associated with the brand but also on the brand’s attitude towards social responsibility and its commitment to positively impacting society and the environment. The ethical practices of an organization can positively impact CENG in several ways. For instance, when consumers witness an organization’s CSR initiatives, they are convinced that the organization is actively contributing to the betterment of society, leading to an emotional attachment to a socially responsible organization (Lichtenstein et al. 2004). This emotional connection is strengthened by the belief that the organization shares its values regarding social and environmental concerns, which can foster a deeper level of commitment to an ethical organization (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001). The implementation of CSR initiatives can also convert consumers into more engaged ones (Loureiro and Lopes 2019). According to Romani et al. (2013), an organization’s ethical commitment to social causes can enhance consumer gratitude and respect, which may lead to a long-term relationship. Emotional engagement is further stressed by Pansari and Kumar (2017).

CENG has been discussed at multiple levels in the literature as a mediating factor in driving consumers’ extra-role behavior (Huang and Chen 2022; El-Naga et al. 2022). In the context of consumer behavior, extra-role behavior may include positive word of mouth, brand advocacy, and continued support and loyalty toward a brand. Several studies have shown that CENG mediates the relationship between various antecedents and extra-role behavior (Abbas et al. 2018; Khattak and Yousaf 2021). CENG, for instance, mediates brand trust (Tingchi Liu et al. 2014) and brand loyalty (Agyei et al. 2021; O’Brien et al. 2015; O’Brien et al. 2018). CENG also mediates consumer citizenship behavior through CSR (Yen et al. 2020). As a result, consumers who perceive an organization to be socially responsible are more likely to spread positive word-of-mouth about it and to recommend it to others, and the degree to which they engage with the organization mediates this effect.

In the context of CENG, stewardship theory suggests that organizations can build stronger relationships with their customers by demonstrating their commitment to CSR. When organizations engage in socially responsible behavior, such as reducing their environmental footprint or supporting charitable causes, consumers may view them more positively and feel a greater sense of trust and loyalty toward the organization. Moreover, organizations can also differentiate themselves from competitors by engaging in CSR and creating a competitive advantage. Consumers are increasingly concerned about the impact of their purchasing decisions on society and the environment and are more likely to support organizations that share their values. Overall, from the perspective of stewardship theory, engaging in CSR can help organizations build stronger relationships with their customers by demonstrating their commitment to responsible stewardship of resources while also creating a competitive advantage and contributing to a more sustainable and ethical business environment. Therefore,

H2:

CSR positively predicts consumer engagement.

H3:

Consumers’ engagement mediates between CSR and consumers’ brand advocacy behavior.

Personal Values and Behavior Formation

Scholars have well discussed the influence of personal values on individual behavior (Vinson et al. 1977; Roccas and Sagiv 2010; Ahmad et al. 2021a). This study refers to the definition of Schwartz (1992), who defines values as “trans-situational in nature that guides individual behavior. Schminke et al. (2015) recognized that values are “building blocks” for behavior formation. Further, the available literature suggests that different individual values influence an individual’s behavioral aspects (cognitive and emotional) (Lee and Trail 2011; Weber 2019; Ardenghi et al. 2021). Specifically, it was emphasized that certain individual values could influence the emotional aspect of consumers. Agost and Vergara (2014) concluded that personal reference values affect consumers’ emotions when evaluating a brand or product. Similarly, Kasambala et al. (2016) found that the personal values of female consumers were important in influencing their emotions when they make a purchase decision. Various other scholars have also documented the relationship between different personal values and emotions (Roccas and McCauley 2004; Wu et al. 2020).

To this end, the impact of ALVS to influence different forms of individual behavior was specified by early researchers in the field (Leung 2008; Kane et al. 2012). As far as consumer behavior is concerned, altruistic values play an important role in shaping individual behavior, particularly extra-role behavior. Prior studies have established a link between altruistic values and consumer citizenship behavior, for instance (Fowler 2013; Yi and Gong 2008). Even some recent scholars have argued about an enhanced level of consumer engagement as an outcome of altruistic values (Leckie et al. 2021). From the standpoint of CSR, Leckie et al. (2021) posited the role of ALVS between CSR and positive word of mouth mediated by consumers’ feelings of gratitude (an emotional aspect of consumer psychology).

Based on stewardship theory, consumers with altruistic values are more likely to engage in advocacy behavior, which involves promoting a cause or issue that benefits society. Altruistic values are often associated with a concern for others and a desire to help improve the world around them. This concern can extend to the products and organizations that individuals choose to support. For example, if consumers hold strong altruistic values, they may be more likely to seek out and support organizations that prioritize social and environmental responsibility, such as through sustainable sourcing, fair labor practices, or charitable giving. In turn, consumer advocacy can help to promote these values and encourage other consumers to follow suit. Moreover, organizations prioritizing social and environmental responsibility are also more likely to be viewed positively by consumers and build stronger relationships with their customer base. By engaging in ethical and sustainable practices, organizations can demonstrate their commitment to responsible stewardship and contribute to a more sustainable and equitable business environment. Thus, we propose the following:

H4:

Altruistic values moderate the mediated path between CSR and consumers’ advocacy behavior via consumer engagement.

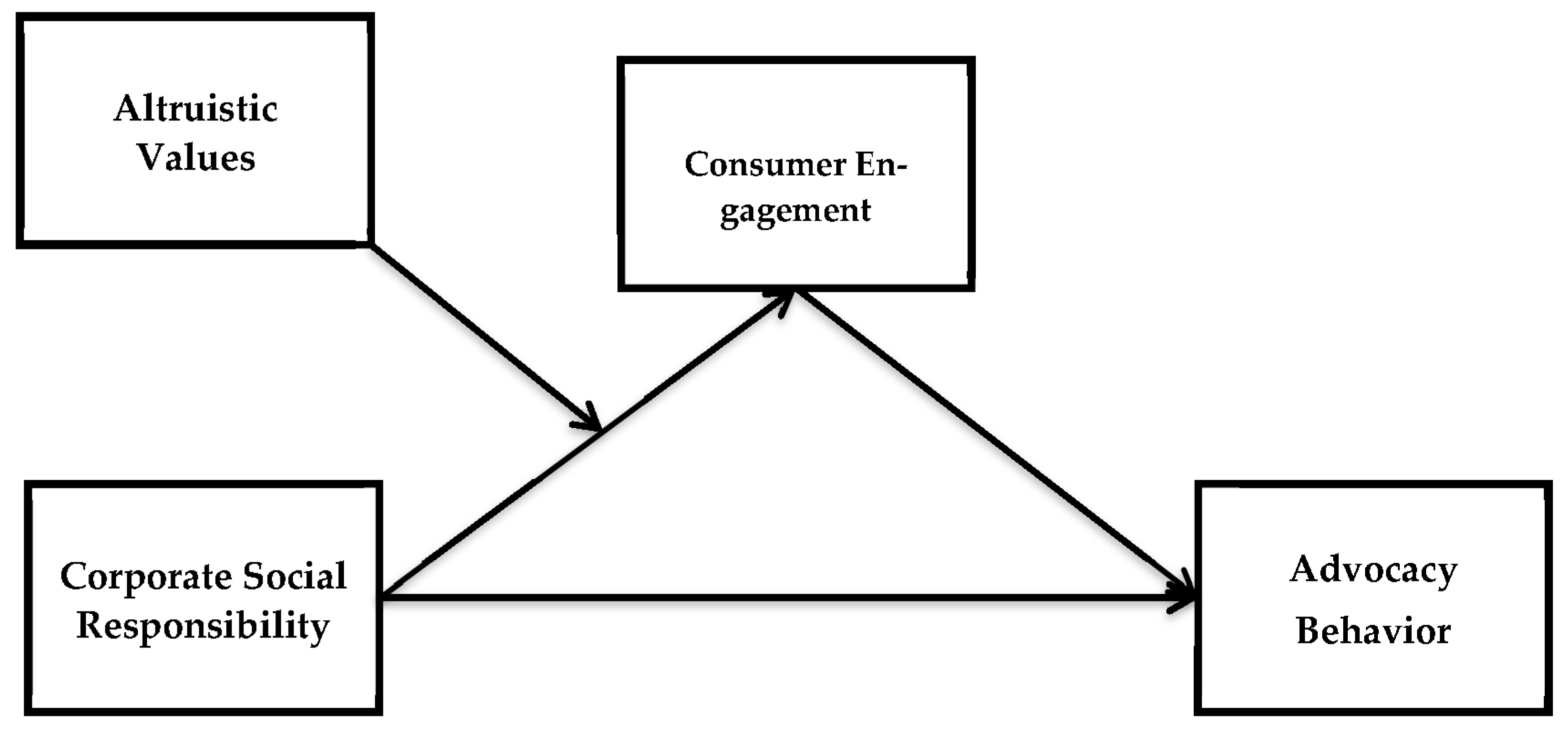

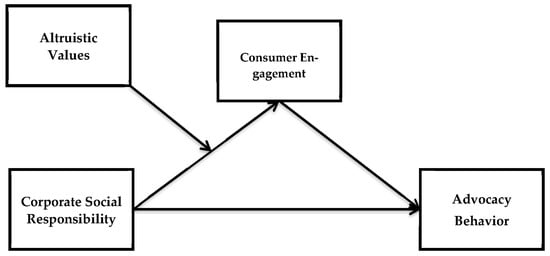

The hypothesized relationships are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed Research Model. CSR = corporate social responsibility, ALVS = altruistic values, CENG = consumer engagement, BADB = brand advocacy behavior.

2. Methodology

2.1. The Study Sector, Sample, and Data Collection

Hospitality consumers in Islamabad and Lahore cities of Pakistan were invited to partake in this data collection activity. The former is the country’s capital, and the latter is the provincial capital of Punjab. From a tourism and hospitality perspective, Islamabad and Lahore are famous and receive special importance from local and international tourists (Sanne 2022). Perhaps this is why all national and international hotel chains exist in these cities. The authors followed a non-probability convenience sampling strategy in this survey. The non-availability of any sampling frame in most consumer surveys (including this study) is one of the reasons that most consumer/employee behavior scholars extensively use this sampling strategy (Kazmi et al. 2021; Coderoni and Perito 2020; Ullah et al. 2021; Ahmad et al. 2021c). Specifically, the consumers were tracked while they were found in a hotel lobby or parking area(s). Prior researchers have also used this consumer tracking strategy in hospitality fields (Ansari et al. 2021; Dharmesti et al. 2020). The hotel administration of the selected hotels cooperated with us (where necessary) in this data-collection activity. For example, the authors were provided proper space/arrangement by the administration to properly interact with the consumers. The authors explained to the hotel administration that the results of this study will be shared with them in order to realize the potential role of CSR to foster the BADB. Prior to approaching a particular hotel organization, the authors pre-checked its CSR engagement. The authors realized that upscale hotel chains had specific CSR plans. For example, Marriott, has a specific CSR plan with the name, “serve 360: Doing good in every direction.” The prime focus of this plan is to reduce water consumption (15%), food wastage (50%), and other wastage (45%). Similarly, Serena hotel has a CSR plan with the name “Karighar” to provide technical and vocational skills to individuals in remote areas of Pakistan (Munaza 2021). Mövenpick has a CSR-related plan Kilo of Kindness to donate food to deprived people (Mövenpick 2023).

Therefore, the authors targeted different upscale hotels in this study. Moreover, the hotel consumers were asked a screening question to know their basic knowledge about CSR.

Regarding the ethicality of this study, the authors, followed the basic steps given in the Helsinki Declaration (Rickham 1964). Since the study was observational and did not involve therapeutic medication, no formal approval from the Institutional Review Board was required. However, every hospitality consumer in this survey was given an informed consent form (attached with every questionnaire). Additionally, the participating consumers were informed that this activity is entirely voluntary and any participating consumer may quit at any stage during the information-sharing process if he or she feels any discomfort in disclosing the information. The data collection activity was completed between September to November 2022.

2.2. Sample Size

The authors estimated an appropriate number of samples for this study by using the A-priori sampling calculator of Dniel (2010). Scholars who use second-generation multivariate data analysis (for example, CB-SEM and PLS-SEM) often use this sampling calculator, especially in social and behavioral sciences (Kuvaas et al. 2020; Dedeoglu et al. 2018). Based on the number of latent and observed variables, probability level, and effect size, this calculator estimates sample size. Using the required inputs, the calculator suggested 352 samples as a suitable size for this study. The authors initially distributed 500 questionnaires to hospitality consumers, knowing that consumer surveys do not produce excellent response rates. In line with the expectation, the authors did not receive a 100% response rate as the authors were able to receive only 382 filled questionnaires. After the screening process (missing responses and outliers) the authors identified 356 valid responses. The socio-demographic detail of the sample is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographics.

2.3. Instrument and Measures

This survey collected responses from hospitality consumers using an adapted questionnaire on a seven-point Likert scale. The respondents received the printed questionnaire and filled it out using paper and pencil. The language of the printed questionnaire was English. The adapted questionnaire was assessed by experts from the hospitality industry and academia to ensure its content validity (Kong et al. 2021). The authors also conducted a pilot study by including different hospitality consumers (not included in the final survey). The pilot study activity revealed that no consumer found any difficulty in understanding the statement of a question.

In specific, the variable of CSR was quantified in this study by using the scale of Alvarado-Herrera et al. (2017), who introduced an 18-item three-dimensional scale to measure consumers’ CSR perceptions in a tourism and hospitality context. One sample item from this scale is “In my opinion, this hotel is trying to help to improve quality of life in the local community”. The authors adapted the scale of Melancon et al. (2011) to quantify BADB (4-items). An illustrated item includes “I would defend this hotel to others if I heard someone speaking poorly about it.” To measure CENG, a 4-item scale was adapted to measure the emotional aspect of consumer engagement from the study of Hollebeek et al. (2014). One sample item from this scale is “I feel very positive when I stay/buy the product/service of this hotel.” Finally, the items of ALVS were adapted from Schwartz (1992), who developed an 8-item scale. One item from this scale is “As a guiding principle in my life, I consider working for the welfare of others.” The authors have provided the full list of items in Appendix A.

2.4. Social Desirability and Method Bias

In order to limit the possible effects of social desirability and common methods bias (CMB), the authors took different theoretical measures (CMB). The questionnaire items were presented randomly to limit any chance of the respondent sequencing the items while filling in the information. In a similar vein, the authors informed every participating consumer that no response was either bad or good and that they need to provide genuine input. Additionally, the authors ensured no statement in the questionnaire should be vague. Similarly, the authors used a shorter version of all scales to limit respondents’ fatigue.

At an empirical level, the authors performed Harman’s single factor test to detect any manifestation of CMB (Harman 1976). The results indicated that the maximum variance shared by a single factor was about 29%, which is less than 50%. This implies that the manifestation of a single dominant factor did not explain more than 50% of the total variance, indicating the absence of any CMB issue. Table 2 provides more details.

Table 2.

Method bias results.

3. Results

3.1. Initial Analysis

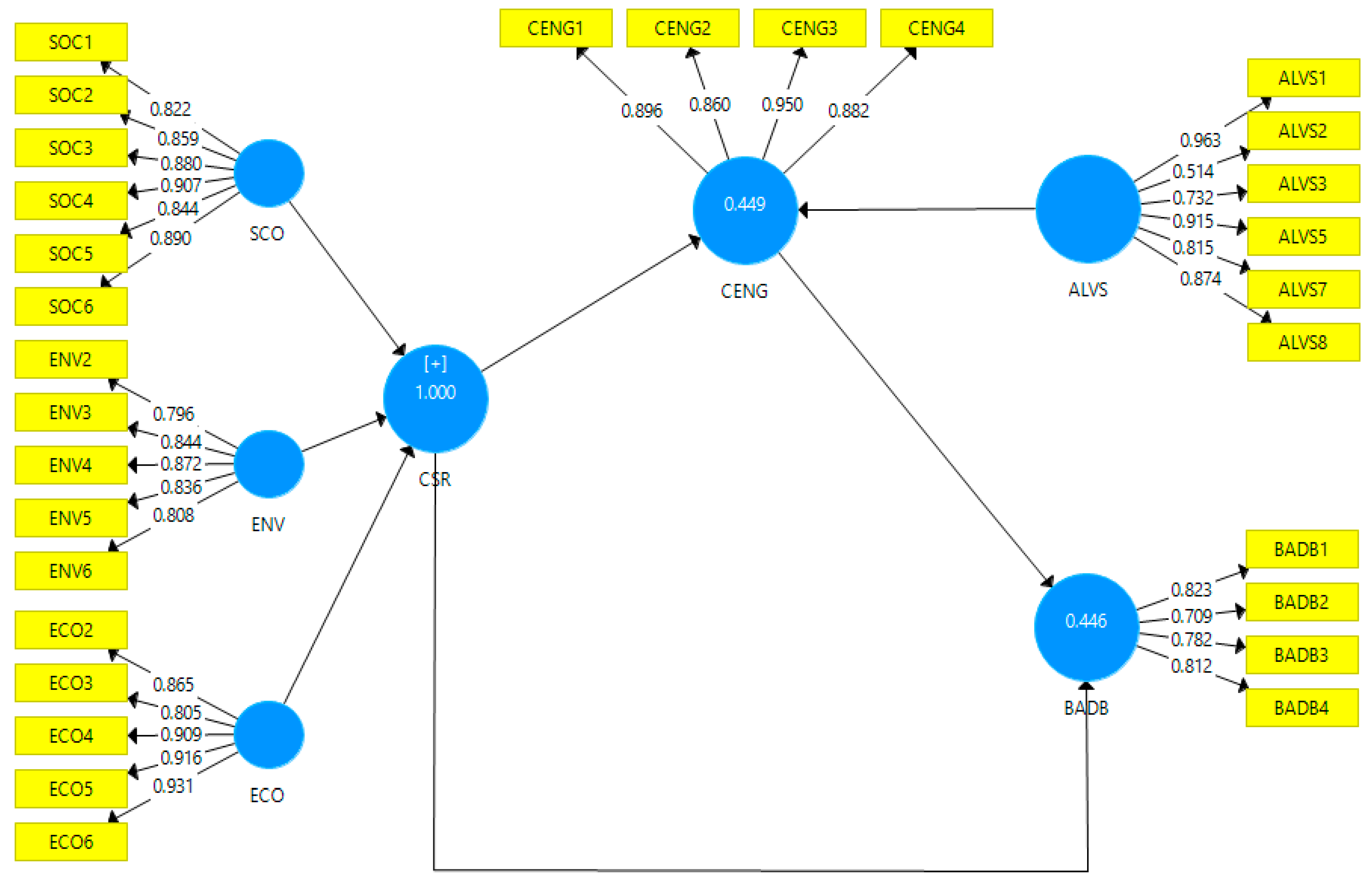

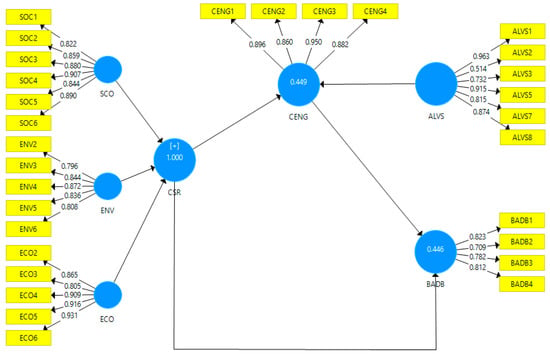

3.1.1. Outer Factor Loadings and Convergent Validity

The authors proceed with the data analysis in this study by performing factor analysis of outer items. The purpose of this activity was to confirm whether each item of a variable significantly loads onto it or not. Ideally, a significant case is where an item of a variable shows a factor loading of 0.70 or greater (Hair et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2023; Chen et al. 2022). In this respect, there were a total of 34 outer items in the measurement model (Figure 2). It was revealed that most of the items’ loadings were significant. However, the authors had to delete four items due to poor factor loadings. Specifically, the authors deleted two items from CSR, and two from ALVS. After removing these weak item loadings, the model showed a significant convergent validity case for all variables. Specifically, the convergent validity was measured by observing all variables’ average variance extracted (AVE) values. The authors have reported these results in Table 3. It can be seen that AVEs ranged from 0.419 (CSR) to 0.806 (CENG). Usually, an AVE value of 0.5 is desired (Ahmad et al. 2022c; Peng et al. 2022; Xu et al. 2022); however, a value greater than 0.35 is also acceptable (Lam 2012; Fornell and Larcker 1981).

Figure 2.

Measurement Model. CSR = corporate social responsibility, ALVS = altruistic values, CENG = consumer engagement, BADB = brand advocacy behavior, SCO = social dimension, ENV = environmental dimension, ECO = economic dimension.

Table 3.

Outer loadings and validity.

3.1.2. Reliability

The reliability of each variable was measured by observing the Cronbach alpha values (>0.7) (Han et al. 2022; Fu et al. 2022), rho_A (>0.7), and composite reliability (>0.7) values. Ideally, if the values in the above cases are 0.7 (Hair et al. 2019) or greater, then these values are considered significant. In this respect, the authors observed that all variables showed significant reliability values for all three criteria. CSR is a case in point where the authors observed 0.906, 0.910, and 0.919 for Cronbach alpha, rho_A, and for composite reliability. The authors have summarized these results in Table 4.

Table 4.

Reliability statistics.

3.1.3. Correlations and Divergent Validity

The authors also analyzed inter-variable correlations and found these positive and significant relations in all cases. For example, inter variable correlation between CSR and BADB was 0.523. The CSR-CENG relationship also showed a positive and significant value of 0.451. The values provided by these tests provide initial support for the hypotheses, particularly H1 and H2. The authors also verified the discriminant validity of each variable. In contrast to convergent validity, discriminant validity establishes whether the items of a particular variable are statistically different from those of other variables. The authors observed all discriminant values were significant as these values were greater than the values of inter-variable correlations. For a case, the discriminant value of ALVS was 0.816, greater than the inter-variable correlations’ values (0.566, 0.487) (Guan et al. 2022; Ahmad et al. 2022a). For more detail, the authors refer to Table 5. Moreover, the authors also tested the HTMT test to further ensure discriminant validity. For a significant HTMT value, it should be less than 0.85 (Hair et al. 2019). As it can be seen from Table 6, all HTMT values were less than the threshold level of 0.85.

Table 5.

Correlations and discriminant validity.

Table 6.

HTMT ratios.

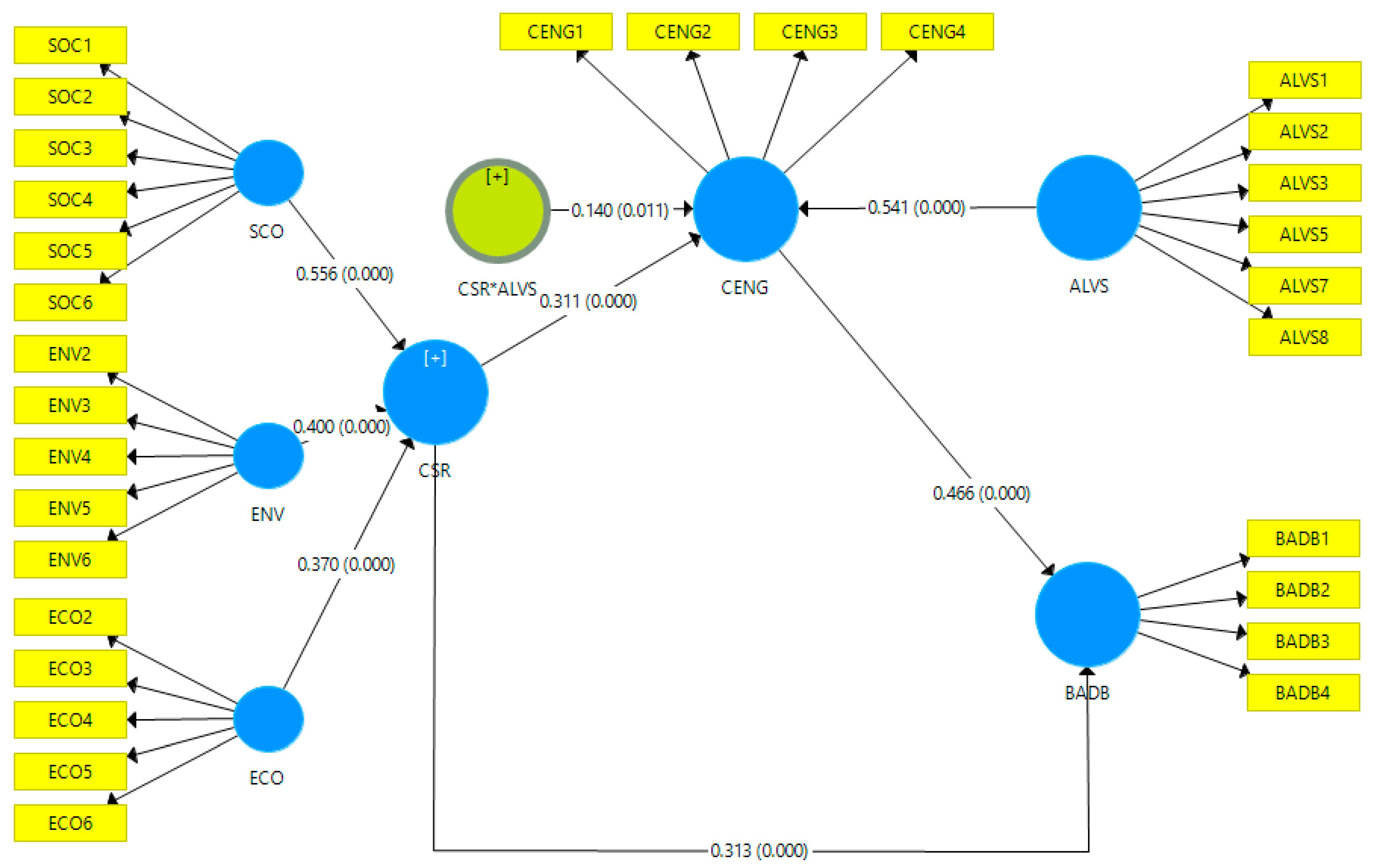

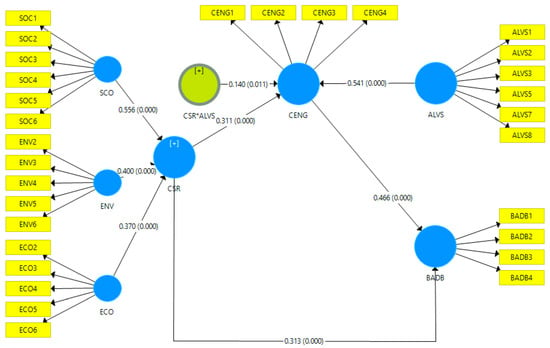

3.2. Structural Analysis

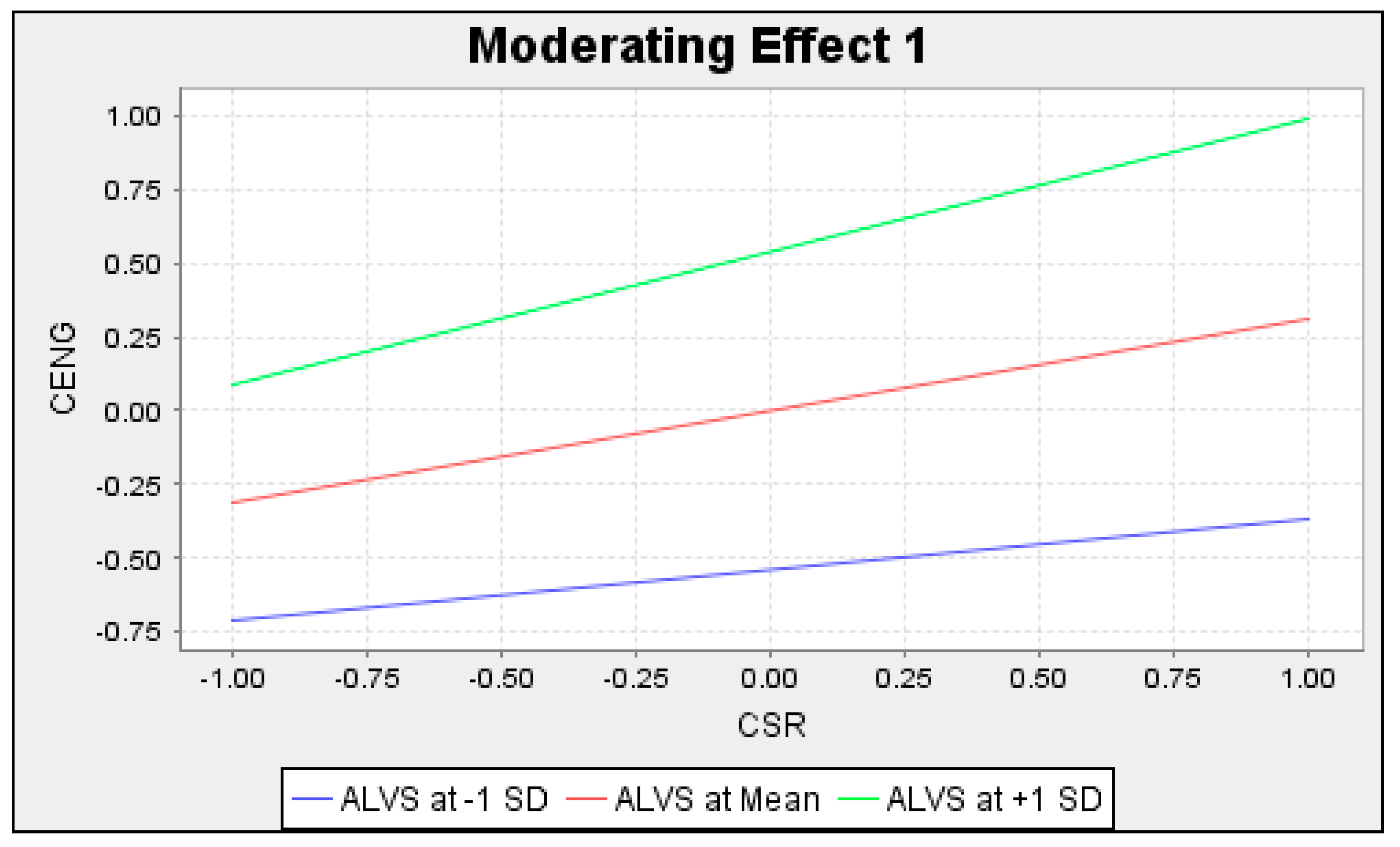

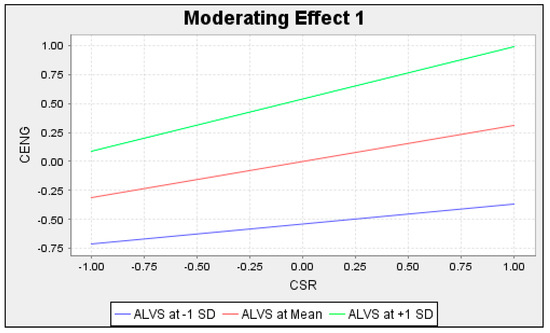

The authors tested the proposed hypotheses by using structural equation modeling. For this purpose, the authors used SMART-PLS software, a modern data analysis application (Guo et al. 2021; Ahmad et al. 2021g; Yu et al. 2021), especially for complex models (like in this study). A bootstrapping sample of 5000 was selected in this study to check the significance of mediation and moderation effects (Ahmad et al. 2021e). The authors have presented the output of different structural relationships in Figure 3. Moreover, a brief summary of the hypotheses evaluation has also been presented in Table 7. In this regard, the empirical results of the structural analysis revealed that the direct relationships were all significant. Especially these results were important to empirically validate the first two hypotheses in this study (H1, H2). Statistically, it was observed that CSR directly and significantly predicted BADB (H1 = 0.313, p < 0.05, T = 6.383, CI = 0.215–0.405) and CENG (H2 = 0.311, p < 0.05, T = 5.343, CI = 0.191–0.419). Hence, based on empirical evidence, H1 and H2 were accepted. The indirect effect in this study was also significant. This was especially important to establish whether there is a mediating function of CENG between CSR and BADB. To this end, the authors realized that there is a partial mediating function of CENG (H3 = 0.145, p < 0.05, T = 4.499, CI = 0.084–0.211). Hence, H3 was also accepted. Lastly, the moderation effect of the interaction term (CSR*ALVS) was also significant. Specifically, this statistical analysis showed that there is a moderating effect of interaction term on CENG (H4 = 0.065, p < 0.05, T = 2.463, CI = 0.006–0.111). These results confirmed the theoretical statement of H4. The authors also tested the moderating effect of ALVS on CENG at three different levels of means (at zero, +1 SD, and −1 SD). The authors revealed that at +1SD, the moderating effect of ALVS was higher than in the other two cases. For further detail, the authors refer to Figure 4.

Figure 3.

The structural model image extracted from SMART-PLS: CSR = Corporate social responsibility, ALVS = Altruistic values, CENG = Consumer engagement, BADB = Brand advocacy behavior, SCO = Social dimension, ENV = Environmental dimension, ECO = Economic dimension.

Table 7.

Structural analysis.

Figure 4.

Simple slope analysis showing the moderating effect of ALVS in the relationship of CSR and CENG at three different levels of mean.

4. Discussion

The specified objectives, as indicated in the introduction part of this study, can now be explained in light of the achieved empirical results. As per the statistical analysis results, the authors confirm that the manifestation of organizational ethics (for example, CSR) significantly determines the BADB of hospitality consumers. In specific, hospitality consumers are expected to positively evaluate the CSR-based actions of an ethical hotel organization which then directly predicts BADB. Different measures taken by a socially responsible hotel administration inculcate the feelings among hospitality consumers that a particular hotel not only considers its own economic benefit but also shows a serious concern for the welfare of all stakeholders, including the community and ecosystems. When consumers see this ‘caring for others’ concern of an ethical hotel organization, they are self-convinced that this hotel assumes self-obligated extra responsibility to take care of all stakeholders as a part of its CSR strategy. In line with the crux of stewardship theory and the process of social exchange, the authors argue that when consumers see the extra-engagement of an ethical hotel in the larger interest of all stakeholders without thinking about whether these stakeholders closely relate to its business operations (the nearby community, employees, consumers, etc.) or not, the consumers are expected to respond positively. In this vein, consumers, too, show extra concern for the prosperity of such an ethical hotel organization and show their advocacy intentions by recommending, endorsing, and defending such an organization within their social circles. Thus, the discretionary behavior of an ethical organization under the umbrella of CSR gives rise to a social bonding between consumers and the organization, and they tend to praise the altruistic social engagement of a socially responsible enterprise. Hence, the results show a positive link between CSR and BADB. This finding is in line with previous researchers, too (Castro-González et al. 2019; Christis and Wang 2021). Moreover, from a hospitality perspective, scholars such as Ahmad et al. (2022b), Latif et al. (2020), Shah and Jan (2021), and Kaur et al. (2022) have also indicated that the manifestation of CSR, in a hospitality organization, may increase the advocacy intentions of individuals including employees and consumers.

Another important objective of this study was to highlight the emotional aspect of human psychology to explain how and why CSR influences the BADB of hospitality consumers. In line with this objective, the authors proposed the mediating function of CENG to explain the underlying logic of the CSR-BADB relationship. In line with the theoretical assumption, the empirical results confirmed the mediating mechanism of CENG to explain the association between CSR and BADB. This is in line with a plethora of CSR scholars who acknowledged the critical role of CSR in influencing different emotional aspects of human psychology (Su et al. 2014; Ahmed et al. 2020). Such mediating function helps to understand how and why CSR sparks the advocacy intentions of hospitality consumers. To this end, the ethical context of a socially responsible hotel organization infuses positive emotions among consumers in the form of CENG. In response to different CSR-based actions of a hotel, the consumers feel an emotional attachment to such an ethical hotel. Specifically, the manifestation of emotional feelings urges hospitality consumers to show their extra motivation to support a socially responsible organization. Backed by an elicit level of positive emotions, the consumers are expected to go the extra mile to support an ethical hotel organization. Indeed, the feeling that a hotel cares for others develops an emotional bond among consumers with a certain hotel. They feel that the organization shares the same concern as they have for society and the biosphere. This leads them towards an enhanced level of engagement with an ethical hotel organization. Hence, CSR activities are helpful for converting consumers into more engaged ones. In response, consumers are expected to stay with an ethical organization as long as possible. Further, not only do they support the ethical concern of a hotel, they also promote such organizations to their social circles. Hence, CSR first improves the CENG of hospitality consumers, which then mediates to explain their advocacy intentions. Prior researchers also confirmed the mediating function of CENG in a CSR context (Abbas et al. 2018; Khattak and Yousaf 2021).

Lastly, this study confirms the moderating role of ALVS in the mediated relation between CSR and BADB through CENG. Specifically, the results show that the manifestation of ALVS in the theoretical framework creates a moderating effect between predictor (CSR) and mediator (CENG) and produces a buffering effect on CENG, which influences BADB. Other researchers have also proposed different human values’ moderating role in guiding human behavior (Chaudhary 2020; Barni et al. 2019). To elucidate further, altruism’s prime focus is considering others’ wellbeing, which is also a focus of CSR. Hence there exists value congruence between the organization and consumers, which, in combination, creates a buffering effect to enhance the engagement level of consumers. Resultantly, consumers with a higher level of engagement backed by ALVS are expected to show a higher level of advocacy intentions. This is because the ALVS of consumers and CSR-based actions of an organization share a common concern for the wellbeing of others. Therefore, when consumers with higher ALVS orientation see the CSR commitment of a hotel organization, they are expected to reward such an organization. All this process ultimately motivates consumers to do extra favor for a particular hotel organization. Thus, from a ‘caring for others’ perspective, consumers give a positive response to such ‘others’ (hotel organizations, for example) by showing BADB. Hence, the authors confirm there is a conditional indirect function of human values, especially ALVS, to foster the advocacy intentions of hospitality consumers.

4.1. Implications

4.1.1. Theoretical Implications

This study significantly enriches the existing body of literature by offering different theoretical insights. Firstly, this study enriches the existing literature on the CSR–consumer behavior relationship from a BADB perspective. In this vein, as the authors indicated at the onset of this study, most CSR scholars explored its role in influencing consumers’ loyalty or purchase preferences (Fernández-Ferrín et al. 2021; Rivera et al. 2019; Sharma et al. 2018). Although these studies were important to spark the existing discussion on CSR and consumer behavior management, neglecting BADB in a CSR context was unwise. Especially from market complexity and competitive advantage perspectives, consumers as advocates bring more benefits to a brand they love than loyal consumers or those with higher purchase intentions. Hence, this study tends to close a critical knowledge gap by proposing CSR as an enabler to foster the advocacy intentions of consumers.

Secondly, in a CSR framework, this study is one of the limited studies highlighting the important role of human emotions in behavior formation. Although the seminal role of human emotions from a behavioral perspective has been discussed in different studies (Patwardhan et al. 2020; Guo et al. 2020), many CSR scholars have proposed rational models to explain different behavioral intentions of consumers (Skawińska 2019; Boccia et al. 2019). Sparking the existing debate on consumer behavior management from an emotional perspective is important because empirical evidence suggests that most of the consumers’ brand purchase decisions are influenced by emotions (Magids et al. 2015). Further, the inefficiency of rational models to explain human behavior has recently been criticized by recent CSR scholars (Kraus et al. 2022; Xie et al. 2019). Hence, the authors bridge this knowledge gap by highlighting the mediating role of consumer emotions (for example, CENG) to explain BADB from the standpoint of CSR.

Thirdly, this study enriches the available body of CSR literature from a perspective of stewardship theory. In this regard, most CSR scholars have promoted a stakeholder theory perspective (Lee et al. 2013; Albasu and Nyameh 2017; Friedman and Miles 2006). Although important, this theory’s instrumental approach undermines the broad spectrum of CSR (Oliver 2017; Filipovic et al. 2010). We, in this regard, propose stewardship theory, which has a normative approach as an alternative to stakeholder theory.

Lastly, this study presents the case of a developing country from a CSR–consumer behavior management perspective, whereas, previously, most of the research was conducted in the context of developed countries (Cho et al. 2014; Verbeeten et al. 2016; Kudłak 2020). Considering the contextual nature of CSR, developed country studies may not reflect the context of developing economies as developed and developing countries differ in many ways.

4.1.2. Practical Implications

Subsequently, this study offers different practical imperatives to the hospitality administration of Pakistan. Specifically, this study highlights the important role of CSR in positively influencing/shaping the advocacy intentions of hospitality consumers. This implication is a very important one, especially from the perspective of the service milieu. This is because, unlike the manufacturing milieu, human dependence in services makes delivering a consistent consumer experience challenging. Additionally, prior testing and service experience are not possible in a service’s context. These points make the role of a personal source of information (for example, advocacy) even more important in a service context. At the same point, considering that consumers prefer personal sources of information over any other form of organization-generated communication (advertising, for example), the important role of CSR from an advocacy perspective should be considered by a hotel administration.

Another important practical insight for the hospitality sector is to address the issue of competitive convergence. Indeed, the isomorphism in physical outlay and service delivery patterns of different players in the hotel sector makes it very challenging for a hotel to hold the existing consumers for a long time and find a stable base of competitive advantage. Hence, promoting customers as brand advocates is really an important tool for a hotel organization for which CSR has a definite role. Therefore, hotel administrators need to understand CSR not only serves the philanthropic purpose of a business but if planned and executed well, CSR-based actions can help a hotel organization to overrun the competitors by increasing the advocacy intentions among hospitality consumers. Hence, considering the market complexities and rivalry in the hospitality segment, this study indicates the important role of CSR in gaining a competitive advantage by converting consumers into brand advocates.

4.2. Limitations and Future Suggestions

Though this study enriches the existing body of literature in many ways and also presents different practical imperatives for the hospitality sector of Pakistan, it still faces some potential limitations which may be addressed in future studies. First, this study only gathered data from two large cities in Pakistan. Although these cities were important from a tourism and hospitality standpoint, the authors identify the geographical concentration of this study may undermine the generalizability of results. Therefore, the authors suggest including more cities in the future may address this limitation. Secondly, due to the unavailability of any sampling frame, the authors did not subscribe to any probability sampling (for example, random sampling) and used convenience sampling. Although it is one of the most employed sampling strategies in many consumer surveys, the authors still suggest that future researchers employ some probability sampling if possible. Cross-sectional data were another issue in our study because they may not reflect an ideal case to predict causal relationships. Therefore, the authors suggest fixing this limitation in future studies using a longitudinal data design.

5. Conclusions

Investigating the intricacies of CSR and its significant impact on hospitality consumers’ advocacy intentions reveals a dynamic network of connections ripe for exploration. The profound findings of this research study illuminate a critical pathway for hotel administrators to capitalize on the transformative power of CSR, thereby fostering a robust foundation for competitive advantage through the canalization of BADB within the hospitality industry’s consumer landscape. In light of these revelations, the authors strongly urge decision-makers within the hospitality domain to meticulously orchestrate a comprehensive CSR blueprint. Such a strategic undertaking must not only satisfy the altruistic obligations incumbent upon hospitality organizations but also present an authentic, tactical opportunity for differentiation, setting them apart from the competitors. Moreover, it behooves hospitality organizations to weave innovative communication stratagems, particularly in relation to the dissemination of CSR-related activities. This stems from the premise that well-informed consumers, adeptly acquainted with the CSR-oriented undertakings of a hospitality organization, will likely impart such knowledge within their social spheres, amplifying the probability of advocacy intentions. Although some hospitality organizations presently engage in dialogue with consumers vis-à-vis their CSR exploits, adopting a more proactive, future-oriented approach to communication could yield huge dividends heretofore unseen. By embracing a visionary stance and conveying their commitment to socially responsible initiatives, hospitality organizations can unlock the potential for enhanced consumer loyalty, thereby bolstering their competitive edge in an increasingly discerning market.

Contrarily, hospitality organizations must fathom the multifaceted implications of CSR, particularly in the context of market complexities and unrelenting competitiveness. This discernment is paramount, given the transient nature of conventional differentiators, such as architectural idiosyncrasies or service delivery patterns, which may be effortlessly replicated by rivals. In this respect, CSR-based differentiation transcends the ephemeral, fostering enduring emotional ties between hospitality organizations and consumers. Emotional connections, as opposed to superficial distinctions, engender profound, enduring, and efficacious relationships that fortify the hospitality organization’s position within the industry. To summarize, the hospitality sector, beset by a plethora of obstacles, including competitive convergence, evanescent innovations, and formidable market complexities, can overcome these challenges through the judicious formulation and implementation of a well-crafted CSR stratagem. Such an approach enables hospitality businesses to navigate industry rivalry while solidifying their standing in an ever-evolving landscape.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A., A.A. and I.S.; Methodology, N.A.; Formal analysis, N.A.; Writing—original draft, N.A.; Writing—review & editing, A.A. and I.S.; Project administration, A.A. and I.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was received.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Considering the observational nature of the study and in the absence of any involvement of therapeutic medication, no formal approval of the Institutional Review Board of the local Ethics Committee was required. All procedures performed were by the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of 33 Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standard. All the procedures were approved by the ethical committee of University of Central Punjab.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from each respondent.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on a reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research is a part of the doctoral dissertation of the principal and corresponding author (Naveed Ahmad).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Items Used in This Study.

Table A1.

Items Used in This Study.

| Corporate Social Responsibility |

| In my opinion, regarding society, this hotel is really trying to sponsor educational programs (SCO1) |

| In my opinion, regarding society, this hotel is really trying to sponsor public health programs (SCO2) |

| In my opinion, regarding society, this hotel is really trying to be highly committed to well-defined ethical principles (SCO3) |

| In my opinion, regarding society, this hotel is really trying to sponsor cultural programs |

| (SCO4)In my opinion, regarding society, this hotel is really trying to make financial donations to social causes (SCO5) |

| In my opinion, regarding society, this hotel is really trying to help to improve quality of life in the local community (SCO6) |

| In my opinion, regarding environment, this hotel is really trying to sponsor pro-environmental programs (ENV1) |

| In my opinion, regarding environment, this hotel is really trying to allocate resources to offer services compatible with the environment (ENV2) |

| In my opinion, regarding environment, this hotel is really trying to carry out programs to reduce pollution (ENV3) |

| In my opinion, regarding environment, this hotel is really trying to protect the environment (ENV4) |

| In my opinion, regarding environment, this hotel is really trying to recycle its waste materials properly (ENV5) |

| In my opinion, regarding environment, this hotel is really trying to use only the necessary natural resources (ENV6) |

| In my opinion, regarding economy, this hotel is really trying to maximize profits in order to guarantee its continuity (ECO1) |

| In my opinion, regarding economy, this hotel is really trying to build solid relations with its customers to assure its long-term economic success (ECO2) |

| In my opinion, regarding economy, this hotel is really trying to continuously improve the quality of the services that they offer (ECO3) |

| In my opinion, regarding economy, this hotel is really trying to have a competitive pricing policy (ECO4) |

| In my opinion, regarding economy, this hotel is really trying to always improve its financial performance (ECO5) |

| In my opinion, regarding economy, this hotel is really trying to do its best to be more productive (ECO6) |

| Altruistic values |

| As a guiding principle in my life, I consider unity with nature (ALVS1) |

| As a guiding principle in my life, I consider preventing pollution (ALVS2) |

| As a guiding principle in my life, I consider protecting the environment (ALVS3) |

| As a guiding principle in my life, I consider respecting the Earth (ALVS4) |

| As a guiding principle in my life, I consider social justice (ALVS5) |

| As a guiding principle in my life, I consider a world at peace (ALVS6) |

| As a guiding principle in my life, I consider myself helpful to others (ALVS7) |

| As a guiding principle in my life, I consider equality (ALVS8) |

| Advocacy Behavior |

| I try to get my friends and family to buy this hotel’s services (BADB1) |

| I seldom miss an opportunity to tell others good things about this hotel (BADB2) |

| I would defend this hotel to others if I heard someone speaking poorly about this hotel (BADB3) |

| I would bring friends/family with me to this hotel because I think they would like it here (BABD4) |

| Consumer Engagement |

| I feel very positive when I stay/buy the product/service of this hotel (CENG1) |

| Staying/buying the product/service of this hotel makes me happy (CENG2) |

| I feel good when I stay/buy the product/service of this hotel (CENG3) |

| I am proud to stay/buy the product/service of this hotel (CENG4) |

References

- Abbas, Moazzam, Yongqiang Gao, and Sayyed Sadaqat Hussain Shah. 2018. CSR and customer outcomes: The mediating role of customer engagement. Sustainability 10: 4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agost, María-Jesús, and Margarita Vergara. 2014. Relationship between meanings, emotions, product preferences and personal values. Application to ceramic tile floorings. Applied Ergonomics 45: 1076–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyei, James, Shaorong Sun, Emmanuel Kofi Penney, Eugene Abrokwah, and Ramous Agyare. 2021. Understanding CSR and Customer Loyalty: The Role of Customer Engagement. Journal of African Business 23: 869–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Bilal, Sajid Iqbal, Mahnoor Hai, and Shahid Latif. 2021a. The interplay of personal values, relational mobile usage and organizational citizenship behavior. Interactive Technology and Smart Education 19: 260–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Naveed, Asif Mahmood, Antonio Ariza-Montes, Heesup Han, Felipe Hernández-Perlines, Luis Araya-Castillo, and Miklas Scholz. 2021b. Sustainable businesses speak to the heart of consumers: Looking at sustainability with a marketing lens to reap banking consumers’ loyalty. Sustainability 13: 3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Naveed, Asif Mahmood, Heesup Han, Antonio Ariza-Montes, Alejandro Vega-Muñoz, Mohi ud Din, Ghazanfar Iqbal Khan, and Zia Ullah. 2021c. Sustainability as a “new normal” for modern businesses: Are smes of pakistan ready to adopt it? Sustainability 13: 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Naveed, Miklas Scholz, Esra AlDhaen, Zia Ullah, and Philippa Scholz. 2021d. Improving Firm’s economic and environmental performance Through the sustainable and innovative environment: Evidence from an emerging economy. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 651394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Naveed, Miklas Scholz, Zia Ullah, Muhammad Zulqarnain Arshad, Raja Irfan Sabir, and Waris Ali Khan. 2021e. The nexus of CSR and co-creation: A roadmap towards consumer loyalty. Sustainability 13: 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Naveed, Rana Tahir Naveed, Miklas Scholz, Muhammad Irfan, Muhammad Usman, and Ilyas Ahmad. 2021f. CSR communication through social media: A litmus test for banking consumers’ loyalty. Sustainability 13: 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Naveed, Zia Ullah, Muhammad Zulqarnain Arshad, Hafiz waqas Kamran, Miklas Scholz, and Heesup Han. 2021g. Relationship between corporate social responsibility at the micro-level and environmental performance: The mediating role of employee pro-environmental behavior and the moderating role of gender. Sustainable Production and Consumption 27: 1138–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Naveed, Zia Ullah, Esra AlDhaen, Heesup Han, Luis Araya-Castillo, and Antonio Ariza-Montes. 2022a. Fostering Hotel-Employee Creativity Through Micro-Level Corporate Social Responsibility: A Social Identity Theory Perspective. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 865021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Naveed, Zia Ullah, Esra AlDhaen, Heesup Han, Antonio Ariza-Montes, and Alejandro Vega-Muñoz. 2022b. Fostering advocacy behavior of employees: A corporate social responsibility perspective from the hospitality sector. Frontiers in Psychology 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Naveed, Zia Ullah, Esra AlDhaen, Heesup Han, and Miklas Scholz. 2022c. A CSR perspective to foster employee creativity in the banking sector: The role of work engagement and psychological safety. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 67: 102968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Ishfaq, Mian Sajid Nazir, Imran Ali, Mohammad Nurunnabi, Arooj Khalid, and Muhammad Zeeshan Shaukat. 2020. Investing in CSR pays you back in many ways! The case of perceptual, attitudinal and behavioral outcomes of customers. Sustainability 12: 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrholdt, Dennis C., Siegfried P. Gudergan, and Christian M. Ringle. 2019. Enhancing loyalty: When improving consumer satisfaction and delight matters. Journal of business research 94: 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albasu, Joseph, and Jerome Nyameh. 2017. Relevance of stakeholders theory, organizational identity theory and social exchange theory to corporate social responsibility and employees performance in the commercial banks in Nigeria. International Journal of Business, Economics and Management 4: 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado-Herrera, Alejandro, Enrique Bigne, Joaquín Aldas-Manzano, and Rafael Curras-Perez. 2017. A scale for measuring consumer perceptions of corporate social responsibility following the sustainable development paradigm. Journal of Business Ethics 140: 243–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Nabeel Younus, Temoor Anjum, Muhammad Farrukh, and Petra Heidler. 2021. Do Good, Have Good: A Mechanism of Fostering Customer Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability 13: 3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardenghi, Stefano, Giulia Rampoldi, Marco Bani, and Maria Grazia Strepparava. 2021. Personal values as early predictors of emotional and cognitive empathy among medical students. Current Psychology 42: 253–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, Daniela, Francesca Danioni, and Paula Benevene. 2019. Teachers’ self-efficacy: The role of personal values and motivations for teaching. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrage, Lint, Eric Chyn, and Justine Hastings. 2020. Advertising and environmental stewardship: Evidence from the BP oil spill. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12: 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, Karen L., B. Andrew Cudmore, and Ronald Paul Hill. 2006. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research 59: 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, Enrique, Juan Manuel Bruno, and Francisco J. Sarabia-Sanchez. 2019. The impact of perceived CSR on corporate reputation and purchase intention. European Journal of Management and Business Economics 28: 206–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Big Commerce. 2022. Word-of-Mouth Marketing: How to Get Happy Customers to Advocate for Your Business. Available online: https://www.bigcommerce.com/articles/ecommerce/word-of-mouth-marketing/ (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Bilro, Ricardo Godinho, Sandra Maria Correia Loureiro, and João Guerreiro. 2019. Exploring online customer engagement with hospitality products and its relationship with involvement, emotional states, experience and brand advocacy. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 28: 147–71. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, Henry, Fortune Edem Amenuvor, Diyawu Rahman Adam, George Cudjoe Agbemabiese, and Robert E. Hinson. 2022. Exploring customer stewardship behaviors in service firms. European Business Review. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, Flavio, Rosa Malgeri Manzo, and Daniela Covino. 2019. Consumer behavior and corporate social responsibility: An evaluation by a choice experiment. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26: 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneva, Miroslava. 2018. Challenges related to the digital transformation of business companies. In Innovation Management, Entrepreneurship and Sustainability (IMES 2018). Prague: Vysoká škola ekonomická v Praze. [Google Scholar]

- Buyapowa. 2022. 92% of Consumers Trust Word of Mouth. Available online: https://www.buyapowa.com/92-of-consumers-trust-word-of-mouth/ (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Calvo-Porral, Cristina, Agustín Ruiz-Vega, and Jean-Pierre Lévy-Mangin. 2018. Does product involvement influence how emotions drive satisfaction?: An approach through the Theory of Hedonic Asymmetry. European Research on Management and Business Economics 24: 130–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cape Town Declaration. 2002. Cape Town Conference on Responsible Tourism in Destinations. Responsible Tourism 2002. Available online: http://www.capetown.gov.za/en/tourism/Documents/Responsible%20Tourism/Toruism_RT_2002_Cape_Town_Declaration.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Carroll, Archie B. 1991. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons 34: 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-González, Sandra, Belén Bande, Pilar Fernández-Ferrín, and Takuma Kimura. 2019. Corporate social responsibility and consumer advocacy behaviors: The importance of emotions and moral virtues. Journal of Cleaner Production 231: 846–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, Richa. 2020. Green human resource management and employee green behavior: An empirical analysis. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 630–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jinyong, Wafa Ghardallou, Ubaldo Comite, Naveed Ahmad, Hyungseo Bobby Ryu, Antonio Ariza-Montes, and Heesup Han. 2022. Managing Hospital Employees’ Burnout through Transformational Leadership: The Role of Resilience, Role Clarity, and Intrinsic Motivation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 10941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Charles H., Giovanna Michelon, Dennis M. Patten, and Robin W. Roberts. 2014. CSR report assurance in the USA: An empirical investigation of determinants and effects. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 5: 130–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christis, Julia, and Yijing Wang. 2021. Communicating environmental CSR towards consumers: The impact of message content, message style and praise tactics. Sustainability 13: 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coderoni, Silvia, and Maria Angela Perito. 2020. Sustainable consumption in the circular economy. An analysis of consumers’ purchase intentions for waste-to-value food. Journal of Cleaner Production 252: 119870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, Arnaldo, Cristela Bairrada, and Filipa Peres. 2019. Brand communities’ relational outcomes, through brand love. Journal of Product & Brand Management 28: 154–65. [Google Scholar]

- Contrafatto, Massimo. 2014. Stewardship Theory: Approaches and Perspectives. In Accountability and Social Accounting for Social and Non-Profit Organizations. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 177–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, Richard, and Janet Smith. 1995. Customer Bonding: Pathway to Lasting Customer Loyalty. Lincolnwood: NTC Business Books. [Google Scholar]