Impact of Inclusive Leadership on Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Job Crafting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Inclusive Leadership

2.2. Job Crafting

2.3. Innovative Work Behavior

2.4. Inclusive Leadership and Innovative Work Behavior

2.5. Inclusive Leadership and Job Crafting

2.6. Job Crafting and Innovative Work Behavior

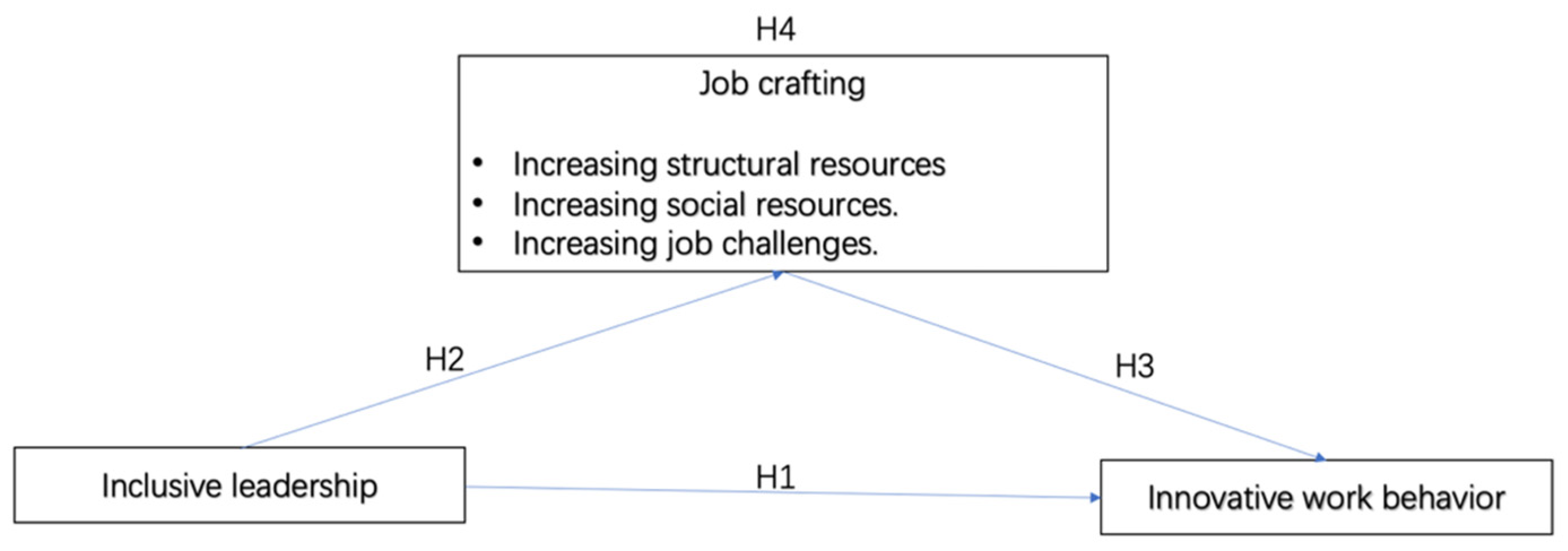

2.7. Mediating Role of Job Crafting and Hypotheses Development

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Instrument Design and Measurement

3.2.1. Innovative Work Behavior

3.2.2. Inclusive Leadership

3.2.3. Job Crafting

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

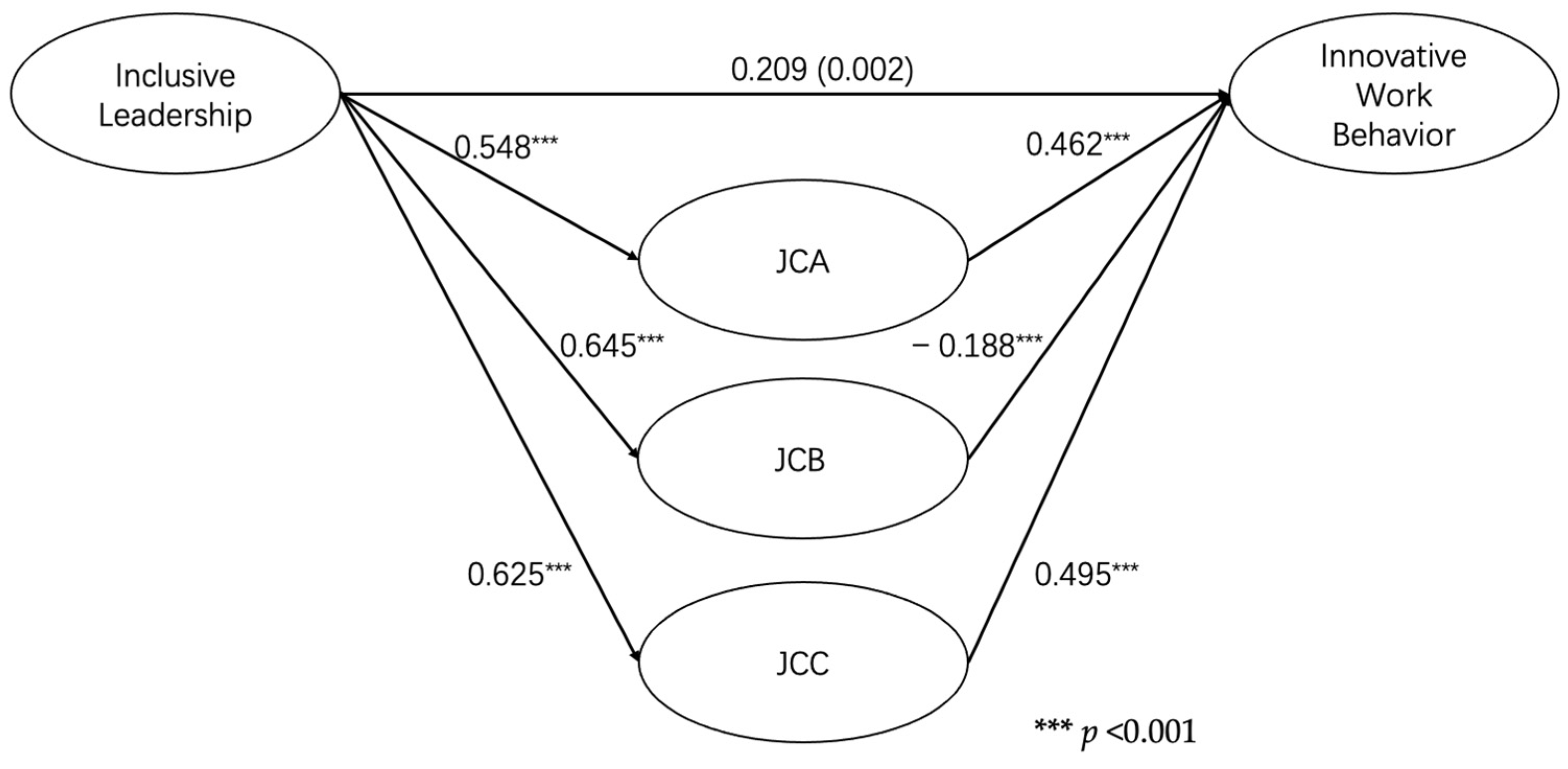

4.2. The Structural Model

4.3. The Mediating Effect

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Practical Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afsar, Bilal, and Waheed Ali Umrani. 2019. Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior: The role of motivation to learn, task complexity and innovation climate. European Journal of Innovation Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, Bilal, Yuosre F. Badir, Bilal Bin Saeed, and Shakir Hafeez. 2017. Transformational and transactional leadership and employee’s entrepreneurial behavior in knowledge–intensive industries. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 28: 307–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikali, Tanachia. 2019. Leading towards inclusiveness: Developing a measurement instrument for inclusive leadership. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Proceedings, Boston, MA, USA, August 1. [Google Scholar]

- Atwater, Leanne, and Abraham Carmeli. 2009. Leader–member exchange, feelings of energy, and involvement in creative work. The Leadership Quarterly 20: 264–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, Afsaneh. 2017. The impact of entrepreneurial leadership on innovation work behavior and opportunity recognition in high-technology SMEs. The Journal of High Technology Management Research 28: 159–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannay, Dheyaa Falih, Mohammed Jabbar Hadi, and Ahmed Abdullah Amanah. 2020. The impact of inclusive leadership behaviors on innovative workplace behavior with an emphasis on the mediating role of work engagement. Problems and Perspectives in Management 18: 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavik, Ali, Yuen Lam Bavik, and Pok Man Tang. 2017. Servant leadership, employee job crafting, and citizenship behaviors: A cross-level investigation. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 58: 364–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudrias, Jean-Sébastien, Alexandre J. S. Morin, and Denis Lajoie. 2014. Directionality of the associations between psychological empowerment and behavioural involvement: A longitudinal autoregressive cross-lagged analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 87: 437–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, Svend. 2010. Character, personality, and identity: On historical aspects of human subjectivity. Nordic Psychology 62: 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, Arianna, and Riccardo Sartori. 2018. The intertwined relationship between job crafting, work-related positive emotions, and work engagement. Evidence from a positive psychology intervention study. The Open Psychology Journal 11: 210–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costigan, Robert D., Richard C. Insinga, J. Jason Berman, Selim S. Ilter, Grazyna Kranas, and Vladimir A. Kureshov. 2006. The effect of employee trust of the supervisor on enterprising behavior: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Business and Psychology 21: 273–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beer, Leon T., Maria Tims, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2016. Job crafting and its impact on work engagement and job satisfaction in mining and manufacturing. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 19: 400–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, Jeroen P. J., and Deanne N. Den Hartog. 2007. How leaders influence employees’ innovative behaviour. European Journal of Innovation Management 10: 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, Jeroen, and Deanne Den Hartog. 2010. Measuring innovative work behaviour. Creativity and Innovation Management 19: 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. 2008. Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Correction to Deci and Ryan 49: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Arnold B. Bakker, Friedhelm Nachreiner, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2001. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Arnold B. Bakker, and Josette M. P. Gevers. 2015. Job crafting and extra-role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. Journal of Vocational Behavior 91: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Yangchun, Xinxing Dai, and Xudong Zhang. 2021. An empirical study of the relationship between inclusive leadership and business model innovation. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 42: 480–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Sage CA. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, Barbara L. 2001. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist 56: 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, Barbara L. 2004. The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 359: 1367–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromkin, Howard L., and Charles R. Snyder. 1980. The search for uniqueness and valuation of scarcity. In Social Exchange. Berlin: Springer, pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- George, Jennifer M., and Jing Zhou. 2007. Dual tuning in a supportive context: Joint contributions of positive mood, negative mood, and supervisory behaviors to employee creativity. Academy of Management Journal 50: 605–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, Charlotte R., and David V. Day. 1997. Meta-Analytic review of leader–member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology 82: 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajar, Mohammed A., Daing Nasir Ibrahim, and Mohd Ridzuan Darun. 2019. Value innovation: The new source of sustainability. Strategic Alliance Between AGBA, Millikin University (USA), IIM-Rohtak (India) and Gift Society (India) 221: 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hakanen, Jari J., Piia Seppälä, and Maria C. W. Peeters. 2017. High job demands, still engaged and not burned out? The role of job crafting. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 24: 619–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirst, Giles, Rolf Van Dick, and Daan Van Knippenberg. 2009. A social identity perspective on leadership and employee creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 30: 963–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. 2002. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology 6: 307–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, Edwin P. 2013. Inclusive leadership and idiosyncrasy credit in leader-follower relations. In The Oxford Handbook of Leadership. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 122–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Leon, and Sebastiaan Rothmann. 2006. Occupational stress, organisational commitment, and ill-health of educators in the North West Province. South African Journal of Education 26: 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, Christian Bøtcher, and Lotte Bøgh Andersen. 2015. Is leadership in the eye of the beholder? A study of intended and perceived leadership practices and organizational performance. Public Administration Review 75: 829–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, Onne. 2000. Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 73: 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, Onne. 2005. The joint impact of perceived influence and supervisor supportiveness on employee innovative behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 78: 573–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, Basharat, Abdul Karim Khan, and Samina Quratulain. 2018. Inclusive leadership and innovative work behavior: Examination of LMX perspective in small capitalized textile firms. The Journal of Psychology 152: 594–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, Basharat, Iqra Abdullah, Muhmmad Adeel Zaffar, Adnan ul Haque, and Ume Rubab. 2019a. Inclusive leadership and innovative work behavior: The role of psychological empowerment. Journal of Management & Organization 25: 554–71. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, Basharat, Sayyed Muhammad Mehdi Raza Naqvi, Abdul Karim Khan, Surendra Arjoon, and Hafiz Habib Tayyeb. 2019b. Impact of inclusive leadership on innovative work behavior: The role of psychological safety. Journal of Management & Organization 25: 117–36. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, Khadija, Humayun Javed, Tariq Mukhtar, and Dewen Qiu. 2019c. Pathogenicity of some entomopathogenic fungal strains to green peach aphid, Myzus persicae Sulzer (Homoptera: Aphididae). Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control 29: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Muhammad Mumtaz, Muhammad Shujaat Mubarik, and Tahir Islam. 2020. Leading the innovation: Role of trust and job crafting as sequential mediators relating servant leadership and innovative work behavior. European Journal of Innovation Management 24: 1547–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Haemi, Jinyoung Im, Hailin Qu, and Julie NamKoong. 2018. Antecedent and consequences of job crafting: An organizational level approach. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 30: 1863–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, Dorien T. A. M., Marianne van Woerkom, Julia Wilkenloh, Luc Dorenbosch, and Jaap J. A. Denissen. 2017. Job crafting towards strengths and interests: The effects of a job crafting intervention on person–job fit and the role of age. Journal of Applied Psychology 102: 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, Mark R. 2007. Motivational and emotional aspects of the self. Annual Review of Psychology 58: 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, Usha, and Minisha Gupta. 2019. An empirical investigation of innovation process in Indian pharmaceutical companies. European Journal of Innovation Management 23: 500–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Chan Tze, and Amran Rasli. 2014. The Relationship between innovative work behavior on work role performance: An empirical study. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 129: 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Carol Yeh-Yun, and Feng-Chuan Liu. 2012. A cross-level analysis of organizational creativity climate and perceived innovation: The mediating effect of work motivation. European Journal of Innovation Management 15: 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lindell, Michael K., and David J. Whitney. 2001. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, Scott B., and Philip M. Podsakoff. 2012. Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. Journal of Retailing 88: 542–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, Michael D., and Samuel T. Hunter. 2005. Innovation in organizations: A multi-level perspective on creativity. In Multi-Level Issues in Strategy and Methods. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 11–75. [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi, Navaz, and Muhammad Shujaat Mubarak. 2019. Negotiating with managers from south asia: India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. In The Palgrave Handbook of Cross-Cultural Business Negotiation. Berlin: Springer, pp. 487–514. [Google Scholar]

- Nembhard, Ingrid M., and Amy C. Edmondson. 2006. Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 27: 941–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, Lisa H., and David M. Mayer. 2009. Do inclusive leaders help to reduce turnover in diverse groups? The moderating role of leader–member exchange in the diversity to turnover relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology 94: 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, Nick. 2020. From knowledge economy to automation anxiety: A growth regime in crisis? New Political Economy 25: 248–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Sharon K., Uta K. Bindl, and Karoline Strauss. 2010. Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management 36: 827–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piansoongnern, Opas. 2016. Chinese leadership and its impacts on innovative work behavior of the Thai employees. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management 17: 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Lei, Bing Liu, Xin Wei, and Yanghong Hu. 2019. Impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior: Perceived organizational support as a mediator. PLoS ONE 14: e0212091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randel, Amy E., Benjamin M. Galvin, Lynn M. Shore, Karen Holcombe Ehrhart, Beth G. Chung, Michelle A. Dean, and Uma Kedharnath. 2018. Inclusive leadership: Realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Human Resource Management Review 28: 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, Quinetta M. 2006. Disentangling the meanings of diversity and inclusion in organizations. Group & Organization Management 31: 212–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rockstuhl, Thomas, James H. Dulebohn, Soon Ang, and Lynn M. Shore. 2012. Leader–member exchange (LMX) and culture: A meta-analysis of correlates of LMX across 23 countries. Journal of Applied Psychology 97: 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, Cort W., Ian M. Katz, Kristi N. Lavigne, and Hannes Zacher. 2017. Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior 102: 112–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Richard M., Kennon M. Sheldon, Tim Kasser, and Edward L. Deci. 1996. All goals are not created equal: An organismic perspective on the nature of goals and their regulation. In The Psychology of Action. Edited by Gollwitzer Peter M. and Bargh John A. London: Guilford, pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Salanova, Marisa, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, Despoina Xanthopoulou, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2010. The gain spiral of resources and work engagement: Sustaining a positive worklife. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 118–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Valle, Raquel, and Daniel Jiménez-Jiménez. 2018. HRM and product innovation: Does innovative work behaviour mediate that relationship? Management Decision 56: 1417–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Susanne G., and Reginald A. Bruce. 1994. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal 37: 580–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, Lynn M., Amy E. Randel, Beth G. Chung, Michelle A. Dean, Karen Holcombe Ehrhart, and Gangaram Singh. 2011. Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of Management 37: 1262–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, Lynn M., Beth G. Chung-Herrera, Michelle A. Dean, Karen Holcombe Ehrhart, Don I. Jung, Amy E. Randel, and Gangaram Singh. 2009. Diversity in organizations: Where are we now and where are we going? Human Resource Management Review 19: 117–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Wendy K., and Michael L. Tushman. 2005. Managing strategic contradictions: A top management model for managing innovation streams. Organization Science 16: 522–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, Gretchen M. 1995. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal 38: 1442–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, Pamela. 2008. Leadership and employee creativity. In Handbook of Organizational Creativity. New York: Erlbaum, pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Tims, Maria, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2010. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 36: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, Maria, Arnold B. Bakker, and Daantje Derks. 2012. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior 80: 173–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, Maria, Arnold B. Bakker, and Daantje Derks. 2013. De Job Demands-Resources benadering van job crafting. Gedrag & Organisatie 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, Mary, Russ Marion, and Bill McKelvey. 2007. Complexity leadership theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era. The Leadership Quarterly 18: 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, Robert J. 2000. Deci and Ryan’s self-determination theory: A view from the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Psychological Inquiry 11: 312–18. [Google Scholar]

- Vandekerkhof, Pieter, Tensie Steijvers, Walter Hendriks, and Wim Voordeckers. 2019. The effect of nonfamily managers on decision-making quality in family firm TMTs: The role of intra-TMT power asymmetries. Journal of Family Business Strategy 10: 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volmer, Judith, Daniel Spurk, and Cornelia Niessen. 2012. Leader–member exchange (LMX), job autonomy, and creative work involvement. The Leadership Quarterly 23: 456–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yi-Xuan, Ya-Juan Yang, Ying Wang, Dan Su, Shu-Weng Li, Ting Zhang, and Hui-Ping Li. 2019. The mediating role of inclusive leadership: Work engagement and innovative behaviour among Chinese head nurses. Journal of Nursing Management 27: 688–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, Logan L, Logan M Steele, and Deanne N. Den Hartog. 2020. Uncertainty avoidance moderates the relationship between transformational leadership and innovation: A meta-analysis. Journal of International Business Studies 51: 138–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, Sandy J., Lynn M. Shore, William H. Bommer, and Lois E. Tetrick. 2002. The role of fair treatment and rewards in perceptions of organizational support and leader-member exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology 87: 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Michael A., and Neil R. Anderson. 1996. Innovation in top management teams. Journal of Applied Psychology 81: 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, Mary-Frances. 2013. From diversity to inclusion: An inclusion equation. In Diversity at Work: The Practice of Inclusion. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 205–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesniewski, Amy, and Jane E. Dutton. 2001. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review 26: 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, Khar Kheng, and Rosli Mahmood. 2013. The relationship between pro-innovation organizational climate, leader-member exchange and innovative work behavior: A study among the knowledge workers of the knowledge intensive business services in Malaysia. Business Management Dynamics 2: 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ziemnowicz, Christopher. 1942. Joseph A. Schumpeter and innovation. Socialism and Democracy 2: 2–4. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Values | Percent | Cumulative Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| GENDER | Male | 26.6 | 26.6 |

| Female | 73.4 | 100.0 | |

| AGE | Younger than 25 | 28.0 | 28.0 |

| 26~30 | 41.4 | 69.4 | |

| 31~35 | 9.9 | 79.3 | |

| 36~40 | 12.5 | 91.8 | |

| Older than 41 | 8.2 | 100.0 | |

| EDUCATION | Undergraduate | 22.4 | 22.4 |

| Bachelor | 60.2 | 82.6 | |

| Master | 15.5 | 98.0 | |

| PhD | 2.0 | 100.0 | |

| POSITION | Ordinary employees | 56.6 | 56.6 |

| First-line managers | 24.7 | 81.3 | |

| Middle managers | 11.2 | 92.4 | |

| Top managers | 7.6 | 100.0 | |

| TENURE | 0~1 | 24.3 | 24.3 |

| 2~3 | 30.9 | 55.3 | |

| 4~5 | 17.1 | 72.4 | |

| 6~10 | 14.1 | 86.5 | |

| 10 and more | 13.5 | 100.0 |

| Dim | Item Reliability | Composite Reliability | Convergence Validity | Discriminate Validity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STD.LOARDING | CR | AVE | IL | IWB | JCA | JCC | JCD | |

| IL | 0.602~0.789 | 0.884 | 0.523 | 0.723 | ||||

| IWB | 0.612~0.775 | 0.877 | 0.544 | 0.651 | 0.738 | |||

| JCA | 0.726~0.828 | 0.854 | 0.594 | 0.548 | 0.680 | 0.771 | ||

| JCB | 0.674~0.797 | 0.836 | 0.506 | 0.645 | 0.310 | 0.354 | 0.711 | |

| JCC | 0.698~0.867 | 0.872 | 0.631 | 0.625 | 0.708 | 0.343 | 0.403 | 0.794 |

| DV | IV | Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | p-Value | R-Square | HYPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JCA | IL | 0.548 | 0.049 | 11.185 | *** | 0.300 | S |

| JCB | IL | 0.645 | 0.043 | 14.851 | *** | 0.416 | S |

| JCC | IL | 0.625 | 0.043 | 14.560 | *** | 0.391 | S |

| IWB | IL | 0.209 | 0.066 | 3.167 | 0.002 | 0.743 | S |

| JCA | 0.462 | 0.055 | 8.433 | *** | S | ||

| JCB | −0.188 | 0.065 | −2.873 | 0.004 | S | ||

| JCC | 0.495 | 0.060 | 8.247 | *** | S |

| Pint Estimate | Product of Coefficients | Bootstrap 5000 Times 95% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias Corrected | |||||

| SE | Est./S.E. | Lower | Upper | ||

| INDIRECT EFFECT | |||||

| JCA | 0.282 | 0.071 | 3.96 | 0.164 | 0.448 |

| JCB | −0.135 | 0.08 | −1.69 | −0.342 | −0.002 |

| JCC | 0.345 | 0.088 | 3.931 | 0.213 | 0.557 |

| TIE | 0.492 | 0.108 | 4.558 | 0.325 | 0.746 |

| TOATL EFFECT & DERECT EFFECT | |||||

| TE | 0.725 | 0.093 | 7.806 | 0.562 | 0.93 |

| DE | 0.233 | 0.109 | 2.15 | 0.016 | 0.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, Y.; Jin, J.; Yim, S.-H. Impact of Inclusive Leadership on Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Job Crafting. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13010004

Guo Y, Jin J, Yim S-H. Impact of Inclusive Leadership on Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Job Crafting. Administrative Sciences. 2023; 13(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Yinping, Junge Jin, and Sang-Hyuk Yim. 2023. "Impact of Inclusive Leadership on Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Job Crafting" Administrative Sciences 13, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13010004

APA StyleGuo, Y., Jin, J., & Yim, S.-H. (2023). Impact of Inclusive Leadership on Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Job Crafting. Administrative Sciences, 13(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13010004