1. Introduction

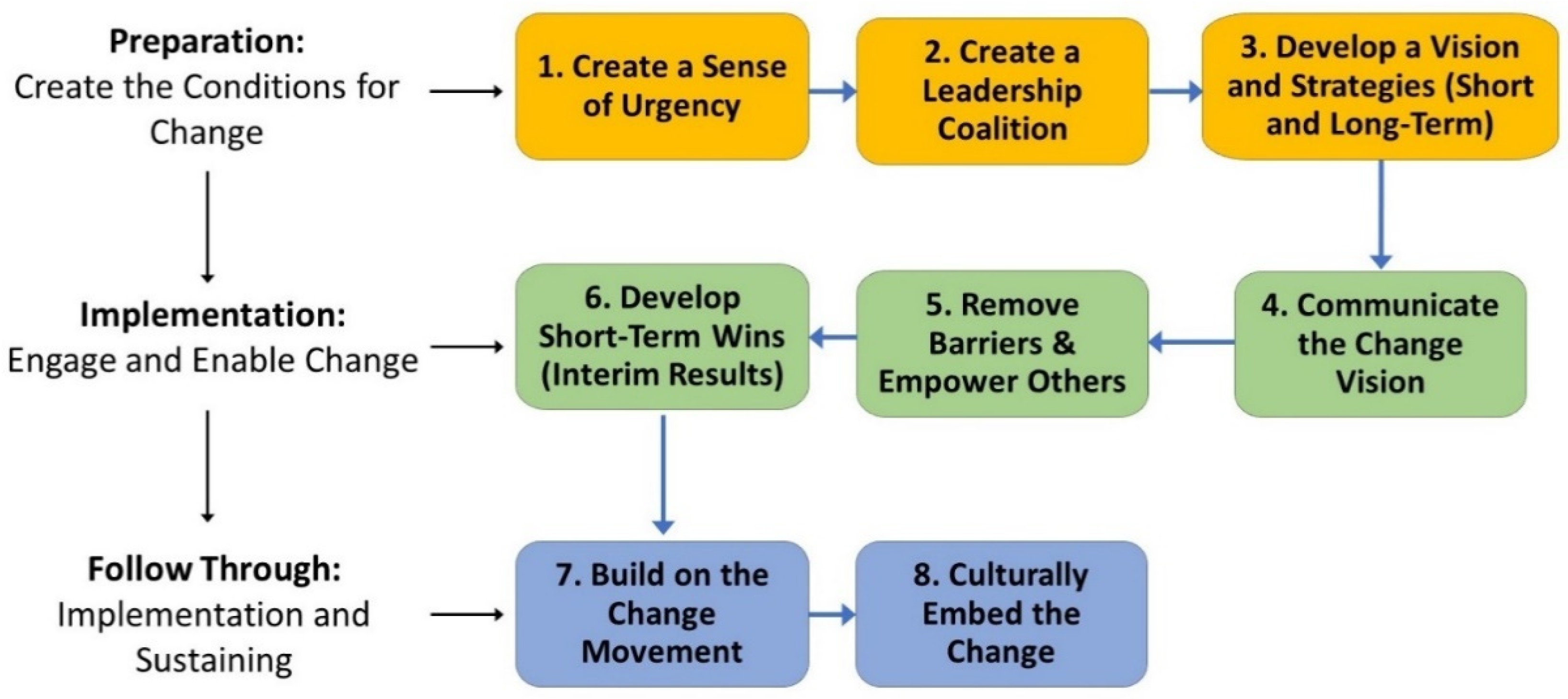

Organizational change has been variously defined as a process in which an organization (e.g., an organized, purposeful group, business, or department) alters minor to major structural components to address operational costs, productivity, and/or service quality deficiencies, identify new growth opportunities, or achieve other organizational goals. There are, therefore, many kinds of organizational change initiatives, including strategic, people-focused, structural, technological, unplanned (like a response to a pandemic), and/or remedial or mitigative change (

Kotter and Schlesinger 1979;

Kotter 2007). The organizational change process usually involves at least three major phases: preparation, implementation, and follow-through (

Stobierski 2020) (

Figure 1). Significant organizational change efforts often help some organizations adapt to industry changes and improve their competitive standing. However, sometimes investment outcomes in organizational change can be disappointing, and the upheaval created by dismantling one organizational model to develop a new one can result in additional challenges (i.e., unintended consequences) beyond those that initiated the change movement in the first place. Unfortunately, the discomfort created amidst change initiatives is often unavoidable, and it may be the acceptance of the truth and subsequent commitment to a change movement that results in buy-in, engagement, and organizational change initiative success (

Moon 2009;

Shtivelband and Rosecrance 2010;

Stokke 2014). The purpose of this communication is to consider the general role(s) of truth and buy-in in the organizational change process. Truth and buy-in are the focus given their critical roles, yet frequent omissions, in organizational change initiatives. Here, truth in the context of organizational change pertains to the “why” change may be necessary, whereas buy-in pertains to stakeholder commitment and engagement in a change initiative. Lacking understanding and acceptance of the “why” (truth) and subsequent buy-in (commitment to engage fully), the likelihood of a change initiative’s success can be limited. This is important because, while current organizational change models may imply truth and buy-in, they are seldom explicitly stated. The objective of this article is not to provide a thorough literature review or consider all potential perspectives or reasons for discontinuities. Nor is it the intent to define all the philosophical underpinnings and complexities of truth and buy-in. The purpose of this article is rather to serve as a reminder of the relevance of truth and buy-in in the change initiative process.

The administrative science of organizational change has been studied for decades (

Tichy 1983), and established tools are available to assist in deliberate approaches to yield optimal outcomes. While there are many models and it is not intended to identify them all here, a few contextual examples are provided. For example,

Kotter (

2012) identified an eight-step people-centric process that focuses on behavioral and strategic actions in a change process (

Figure 1). The Lewin model (

Sarayreh et al. 2013) works in three phases, including: (1) loosening (preparing for change), (2) change (transition to the new state), and (3) consolidating (solidifying the new culture). These are similar to the phases presented by

Kotter (

2012) and shown in

Figure 1. McKinsey’s 7-S model is another organizational change tool that divides a change initiative into seven distinct components (

Peters and Waterman 2011); the ADKAR change management model (

Tang 2019) emphasizes five key phases, including a desire phase that requires acts of persuasion until everyone involved is in support (i.e., buy-in) of the proposed change(s). The Kubler-Ross change management curve is another example (

Kearney and Hyle 2006), and there are many others. Unfortunately, and despite the progress of recent decades, truth and buy-in are not explicitly described in organizational change process models.

The eight phases in

Figure 1 can be considered and applied differently depending on the organization and the organizational change effort needed.

Kotter (

2012) described what might happen if the eight steps are not followed. These may be considered in terms of change initiative process errors that often result in organizational change failures. Therefore, they also serve as precautionary warnings about challenges that may arise if truths about organizational change are not clearly communicated and buy-in is not achieved early on and nurtured throughout a change initiative. Revised and reworded from

Kotter (

2012) and corresponding to the eight organizational change integrated steps shown in

Figure 1:

Leadership should be sensitive regarding complacency. Complacency is often the product of not establishing a strong enough sense of urgency regarding the need to change. Complacency can be a roadblock, if not entirely derail organizational change initiatives;

There must be a strong and unified leadership team. The leadership team (which may include leaders and/or managers) must fully buy into the change initiative to convey a strong enough sense of urgency regarding the need for change. Lacking absolute buy-in, a change leadership team may lack unity and thus momentum to successfully implement a change initiative;

Lacking a powerful and obtainable vision (i.e., what the future of the organization can look like) for the future state of a given organization, it is difficult to change, i.e., unless you know where you are going, it is challenging to implement the correct strategic changes to get you (or your organization) there;

The unified leadership must be willing to communicate the vision significantly, if not excessively. If the vision and justification for organizational change are under-communicated, the result is often a failed change initiative;

If leaders allow obstacles to slow the progress of a new vision, reasons for complacency increase. It is essential for leadership to fully commit to removing barriers to any organizational change;

Lacking short-term wins, a change initiative can become overwhelming. Having a long-term vision that includes interim results (interim wins) is essential. The short-term wins boost morale and energize the team to keep working hard to achieve the long-term vision;

It is crucial to avoid the temptation to declare premature organizational change success. Culture changing organizational change can take three–ten years (or more). It is essential to not become complacent after a few short-term wins;

It is critical to avoid easing up on a change effort before instituted organizational changes become rooted in the organization’s culture. Again, this can take three–ten (or more) years. Instituted organizational changes must become embedded in the social culture of the organization. This takes time and ongoing diligence.

Given the critical importance of messaging truth, obtaining buy-in, and developing a unified leadership team, it may be helpful to discern between the roles of managers and leaders, as each may (or may not) have different functions in the delivery(ies) of truth and obtaining buy-in before, during, and after a change initiative. While leader–manager hybrids are undoubtedly common, distinctions between the two may be necessary for change initiative strategic implementation. While a manager may be tasked to help accomplish what is already known, leaders are often the individuals who direct organizational development trajectories and, therefore, change (i.e., when to apply a manager or leader skill set may be exceedingly important). Leadership, thus, builds on existing systems and transforms old ones, developing paths towards new, possibly undiscovered territory that may be critical to advancing a complex change agenda (

Hubbart 2022;

Jabri and Jabri 2022;

Kotter 2007,

2012;

McKenna 2020). Thus, leaders are agile agents of change (

Caldwell 2003). Notably, while the leader may decide what changes need to occur, the manager may need to demonstrate unity with the leader in terms of reaching objectives because it is often the manager that is more fully engaged with the workforce, making sure that the change is seen through. Ultimately, clarity in vision, justifications for change, and great empathy are essential for all members of the change leadership. Leadership teams must therefore be versatile, agile, and able to maneuver with changing organizational conditions. Leaders and managers must ultimately be able to convey a unified truth in their reasoning for change if a change initiative is to succeed.

2. Truth and Buy-In in Organizational Change

There may be no truer truth than how difficult it can be to accept the truth under any circumstance. Furthermore, acceptance of truth, the semantics of truth-telling (

Stokke 2014), and buy-in (

Kotter and Whitehead 2010) are arguably the most significant obstacles to short- and long-term organizational change movement success. Indeed, to many, accepting that something about us as individuals or as a collective organization may be wrong may be highly unpalatable. This is especially true when accepting delinquency(ies) may necessitate significant personal and/or organizational change (

Kotter 2012;

Levine and Cohen 2018). Despite these potential discomforts, truth and buy-in are critical and unavoidable steps in the organizational change process. This is important because avoiding the truth restrains our ability to grow, change, develop, and evolve as individuals or as an organization. Unfortunately, avoidance of the truth in the business world is all too common. For example, an employee may retain certain information so that it does not reach supervisors and result in a change of process, or perhaps worse, disciplinary action. A subset of an organization, such as a division or a department, may avoid sharing truthful information (such as productivity) that may result in negative perceptions of their peers or administration, or worse, dissolution. Resistance to acceptance of the truth may also be based on historical cultures of organizational habit (i.e., the way it has always been done) or fear of the unknown (

Levine and Cohen 2018). The unknowns can include anticipated future norms should a change initiative succeed or even unexpected outcomes (that could be less positive or highly negative) should the initiative succeed or fail. Resistance to truths can also be attributed to a lack of preparatory skills (training) or even threats to a dominant power base and an inability to imagine alternatives that may result in new opportunities for growth, efficiencies, and opportunities for those engaged in the change movement (

Agocs 1997;

Tichy 1983). The truth may also pertain to the consequences of not changing organizational operations in ways that result in advancement, the result of which may include being left behind and potentially out of business. Ultimately, in any organization, acceptance of what may be inconvenient truths is essential for organizational evolution and advancement and critical to obtaining workforce buy-in (

Shtivelband and Rosecrance 2010). It should also be acknowledged that organizational change is likely unnecessary lacking deficiencies. However, making a change, whether personal (employee level) or organizational, requires acceptance of a deficiency (e.g., a behavioral or procedural failure). It is only when that truth is accepted that change can occur because complacency is often no longer an issue with acceptance of the truth and commitment to change (buy-in). This is because those who might otherwise be complacent have accepted the truth, bought in, and are engaged in the change. Operationally, a truth-telling and acceptance phase would be navigated before or in concert with step #1 in

Figure 1 and would be continued as needed throughout the change initiative. This process is challenging and requires a great deal of strategic thinking and empathy on the part of leadership. Empathy is critical at this stage because accepting the truth(s) that lead to a successful organizational change initiative can be similar to the typical phases of grief. Those phases often include denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and finally acceptance (i.e., buy-in) ((

McAlearney et al. 2015;

Romadona and Setiawan 2021), and references therein) (

Figure 2).

Buy-in in the context of organizational change can be considered an honest, reciprocal agreement between leaders and members (stakeholders) of an organization to work together to navigate a successful change initiative. It is a commitment to the process of organizational change, and it involves trust between change agents and stakeholders (

Moon 2009). In this context, stakeholders are individuals that can affect or be affected by a given organizational change initiative. In practice, stakeholders commit (by varying degrees) to supporting a change initiative to help it succeed to fruition. It is a commitment from organization members to support the vision of leadership, and it is a mutual commitment from leadership to work to gain and sustain the buy-in of their stakeholders. This latter point is important because one of the most critical factors for success in change initiatives is the extent to which leadership is willing to commit fully, from the beginning, to honest, open, truthful, reciprocal, and empathetic conversations with stakeholders. It has further relevance because articulating truths to gain buy-in to address a challenging organizational viability situation (e.g., often core productivities and efficiencies) requires an honest assessment of the employee and organizational behavior and excellent skills in listening and empathy (

Levine and Cohen 2018;

Stokke 2014). It is worth acknowledging that processes of garnering buy-in through acceptance of truths may be ignored, and there may be some success with change initiatives regardless. However, lacking investment in stakeholder buy-in at all levels of an organization, the likelihood of a change initiative’s success is very low. Indeed, approximately 70% of organizational change efforts fail, and a leading reason for failure is a lack of stakeholder buy-in. As

Kotter and Whitehead (

2010) explained, a significant problem in obtaining buy-in is often the approach. Often, leadership will take a describe-and-defend approach instead of a collaborative, partnership approach. The former usually takes less time commitment on the part of the leader but can result in resistance; the latter often takes more time commitment on the part of the leader but often results in buy-in due to the trust developed through a more deliberate, collaborative process. This latter point is vital because genuine buy-in usually requires at least some element of co-creation. At a minimum, co-creation can require discussion, debate, and an opportunity for participants to feel vested in an inclusive and equitable decision-making process (

Kotter and Whitehead 2010). Ultimately, the greater the employee (and all stakeholders’) buy-in, the higher the likelihood of success of any change initiative.

There have been a variety of research investigations to elucidate the most effective ways to obtain stakeholder buy-in. For example, three overarching strategies, or themes, were identified by

Applequist et al. (

2017) for getting buy-in, including (1) providing opportunities for effective communication and feedback, (2) supplying appropriate reinforcement techniques that can encourage ongoing engagement, and (3) identifying a change initiative leader. The final strategic point is important because studies have repeatedly shown that obtaining buy-in for change is most successful when a clear champion or change initiative leader is present (

Lewis and Seibold 1998;

Lewis 2007;

Lewis and Seibold 1993). This implies that the selection of the change leader should be very deliberate. Studies showed that for a leader to succeed in motivating and sustaining buy-in through an organizational change initiative, they must be trusted sources of guidance in leading others. This is particularly important during the first stages of a change initiative (

Hendy and Barlow 2012) (

Figure 1). Of further importance, these trusted emissaries of a change initiative must serve as guides or coaches that facilitate trust and buy-in with stakeholders.

Fortunately, some tools have been developed to assist change leaders. For example, seven communication strategies were described by

Mazzei (

2014) to promote employee buy-in and engagement during change initiatives, including (1) creating a communication pathway, (2) adopting a transparent style, (3) building trust, (4) providing training to managers in how to become effective communicators, (5) increasing awareness and thus accountability for organization values, (6) conveying the mutual benefits for employees and the organization of a proposed organizational change initiative, and (7) adopting small practices that encourage and reinforce stakeholder (employee) motivation. To successfully deliver these approaches, a change leader must remain self-aware and empathetic to organizational stakeholders. A process was proposed by

Moon (

2009) to emphasize the importance of a change leader’s ability to tune in to self-awareness and remain flexible to adapt to challenges amidst a change initiative. The importance of staying flexible in a dynamic change initiative landscape, including the ability to adapt to stakeholder complacency and apathy, was similarly addressed by

Kotter (

2007),

Kotter and Whitehead (

2010), and

Kotter (

2012).

Moon (

2009) aimed to develop a mechanism to increase the buy-in among organization stakeholders through common sense perspectives. Said differently,

Moon (

2009) showed that views of common sense or points of logic may provide the most effective positive argumentation towards garnering buy-in and, therefore, result in change initiative success. Delivering pragmatic arguments requires a strong sense of self-awareness and flexibility in approach on the part of the change leader. Maintaining the requisite levels of self-awareness can become very challenging for change leaders, considering all the pressures and perturbations from multiple organizational interests that can affect decision-making. These pressures can distract the change leader from remaining diligent to the stakeholders that need logical (common sense) argumentation and are responsible to the greatest extent for upholding the organization. Lacking the ability to remain self-aware through such a process can result in self-sabotage by the leader and, ultimately, failure of a change initiative (

Kotter and Whitehead 2010;

Kotter 2012;

Moon 2009). If successful, however, it is through this process that change leaders and stakeholders can begin to focus on solving the problems that have led to the moment of change. Through this process, close collaboration can be achieved between the leaders, managers, and stakeholders who will see a change initiative through to completion.

3. Implications and Applications

The importance of truth and buy-in is often underappreciated but stretches far beyond organizational change and has been shown to positively influence organizational work performance, commitment, satisfaction, and turnover when applied as standard practices (

O’Sullivan and Partridge 2016). Under change initiative circumstances, ample evidence suggests that truth and buy-in must be navigated early, if not well before any organizational change movement is initiated. It should also be acknowledged that if effective communication, stakeholder engagement, and buy-in exist in an organization, change initiatives can be far less negatively impactful and more about a standard (unified) acceptance of normal marketplace adaptation. Thus, leadership should always communicate truthfully and transparently with stakeholders to maintain persistent and sustained buy-in and trust. The organization will then be well-positioned and malleable when change initiatives become necessary.

These ideas may be helpful in many industries, organizations, and disciplines that do not often use organizational change approaches. For example, organizations such as the global agriculture industry may need to achieve global buy-in to feed a future human population of over nine billion people (

Hubbart 2022). Or organizations such as higher education (colleges and universities) may need to rethink how they recruit and retain students, faculty, and staff. Or scientific disciplines such as climate science may wish to affect public thinking about carbon generation or sequestration and climate change impacts at regional, continental, and global scales. In all these cases and a myriad of others, there is a need to convey the truth and advance credibility through effectively communicating scientifically supported truths to obtain commitment (buy-in) to change (

Allchin 2020;

Kotcher et al. 2017;

Yamamoto 2012). For the examples provided here, accepting these truths may include that we are not currently able to feed a planet of over 9 billion people and that a great deal of global organizational change must occur with the highest degree of buy-in to navigate this challenge successfully. Or that in higher education, public perceptions and enrollments may be dropping for various reasons. New innovative changes must be implemented to increase public confidence and attract diverse populations of students towards equitable and inclusive degree programs that prepare them for the dynamic futures they envision. Or that climate scientists may need to share inconvenient truths about scientific findings while building public confidence and trust so that policies might be enacted that will change an uncertain climate future. Ultimately, the applicable concepts of truth and buy-in range from the individual to multi-thousand stakeholder industries. The ideas are inter- and multi-organizational and may therefore be helpful at all levels and in all types of organizations.

4. Conclusions

Amidst organizational change initiatives, effective in situ communication leads to understanding, trust, and buy-in. The concepts of trust and buy-in are implicit in the terminologies used in discussions of organizational change. These ideas are fundamental in current socio-political times, considering the imperative for equitable and inclusive advancement teams that must be skilled to address a highly complex and often global-scale economy. Unfortunately, while the ideas presented in this article are often promoted, they are seldom practiced or are practiced in isolation from each other, perhaps randomly, and often out of sync amidst organizational change initiatives when they are most greatly needed. It is often during a moment of organizational change that leaders fear the failure of the change initiative and loss of confidence in their role(s), and it may be because of that anxiety that critical steps in the change process(es) are omitted (inadvertently or overtly). There is, however, very little doubt that buy-in increases when leaders regularly engage in stakeholder communication exercises before and during a change initiative, thereby often offsetting inherent leadership anxieties. Ultimately, this is unavoidable hard work. If a leader cannot engage in such activities due to focus and pressures in many other areas, an emissary should be appointed to carry out these roles. Ultimately, change is a constant in all successful organizations, but without truth and buy-in at all levels, organizational change success is nearly impossible. Fortunately, a great deal of research and many tools are available to guide leadership during moments of change. However, during these inevitable moments, it is critical to always consider the importance of truth and buy-in for organizational change success.