Abstract

The success factors and challenges of interorganizational collaboration have been widely studied from different disciplinary perspectives. However, the role of design in making such collaborations resilient has received little attention, although deliberately designing for resilience is likely to be vital to the success of any interorganizational collaboration. This study explores the resilience of interorganizational collaboration by means of a comparative case study of Dutch maternity care providers, which have been facing major challenges due to financial cutbacks, government-enforced collaborative structures, and the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings make two contributions to the literature. First, we further develop the construct of interorganizational resilience. Second, we shed light on how well-designed distributed decision-making enhances resilience, thereby making a first attempt at meeting the challenge of designing for interorganizational resilience.

1. Introduction

Complex societal challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic urge the investigation of what drives the resilience of health care organizations (e.g., Cosentino and Paoloni 2021). Such unexpected shocks also require collaboration between organizations, especially when they cannot address these challenges on their own (Chesley and D’Avella 2020; Huxham and Vangen 2005). Collaboration then serves as a means for organizations to deal with a turbulent and complex environment (Wood and Gray 1991) and obtain a competitive advantage (Kanter 1994). However, interorganizational collaborations are often difficult to sustain, especially when each participating organization needs to find a balance between collaborating and engaging with one another and simultaneously maintaining their autonomy (Chesley and D’Avella 2020).

In this respect, interorganizational collaborations tend to draw on heterarchical organizational designs, that is, structures in which the various elements are highly interdependent and hierarchy is absent. Such designs are associated with members having equal power or similar rights to coordinate activities, often resulting in extensive (i.e., time-consuming) mutual adjustment and consensus building (Gulati et al. 2012). In these heterarchical structures, power is dealt with in a more dynamic and fluid sense than in hierarchical structures (Aime et al. 2014). Heterarchical structures, therefore, have important consequences for power dynamics within interorganizational collaboration, especially in relation to trust. It is often difficult to develop trust under non-hierarchical circumstances (Hardy et al. 1998; Ring 1997). Traditionally, collaborative relationships between individual professionals in maternity care are also determined by status differences, which have led some professionals (e.g., gynecologists) to feel superior (i.e., as if they possess more decision-making power) than other professionals (e.g., obstetricians), which may further impede the development of trust. That is, such a status hierarchy does not invite professionals to communicate across professional boundaries (Edmondson 2003). In developing trust in the collaboration, psychological safety plays an important role (cf. Edmondson 1999): participants need to speak their minds to create mutual understanding.

There are many challenges in interorganizational collaboration in healthcare, such as coming up with adaptive solutions when demand strongly increases but few resources are available (Kennedy et al. 2019; Suter et al. 2009). In this respect, a lack of collaborative capability can negatively impact the care delivered to patients or clients (Zwarenstein et al. 2009). The complexity of health-related issues and the domain-specific knowledge of individual professionals in (e.g., home or maternity) care often severely restricts their ability to come up with integral solutions (Orchard et al. 2005). This suggests the design of interorganizational collaboration structures may be vital for effectively dealing with major challenges such as COVID-19. These structures can facilitate and enhance adaptation to the disruption (Eisenman et al. 2020). More specifically, structures with less hierarchy and more decentralized decision-making processes may cultivate the collaboration’s resilience (Mosca et al. 2021). This calls for heterarchical as opposed to hierarchal structures and, by extension, more distributed decision-making at the interorganizational level.

Few studies have addressed the impact of organizational design on organizational resilience (Eisenman et al. 2020; Välikangas and Romme 2013). This design challenge is even greater at the interorganizational level because interorganizational collaboration cannot be organized in traditional ways (Alberts 2012; Palumbo et al. 2020). Since collegiality instead of hierarchy is likely to result in better outcomes for patients (Feiger and Schmitt 1979), hierarchical status differences in interorganizational collaborations appear to have direct consequences for the care delivered, for example, measured in terms of death rates among newborns (cf. van der Velden et al. 2009).

In the Netherlands, maternity care involves health care professionals often engaging in interorganizational collaboration. These collaborations typically involve hospital-based professionals such as gynecologists but also (e.g., self-employed) professionals that visit clients’ homes, such as obstetricians and maternity care assistants. Notably, in the Netherlands, a substantial part of all child births takes place at home (with help of an obstetrician), in contrast to most other European countries. Dutch maternity care professionals have thus been long aware of the necessity to engage in interorganizational collaboration to be able to deliver joint solutions.

This study seeks to understand how collaboration in Dutch maternity care benefits from heterarchical structures. Accordingly, we investigate how the design of interorganizational collaboration impacts its resilience. We adopt a comparative case study approach to analyze two cases of interorganizational collaboration in maternity care in the Netherlands. In doing so, this study contributes to the extant literature by providing a novel perspective on interorganizational collaboration and resilience.

2. Background

2.1. Interorganizational and Interprofessional Collaboration

Interorganizational collaboration entails both cooperation and coordination. Cooperation requires commitment and aligned interests from all participants, whereas coordination requires effective alignment and adjustment of actions in exchanging knowledge, products or services (Gulati et al. 2012; Jones et al. 1997). Some of these exchanges may be made through temporary organizational forms, brought to life to tackle challenges in a complex and volatile environment (Bigley and Roberts 2001). These interorganizational collaborations often involve distinct professional disciplines. As such, the term ‘interorganizational’ refers in this study also to ‘inter-professional.’ Interprofessional collaboration is conceived as “the process of developing and maintaining effective interprofessional working relationships with learners, practitioners, patients/clients/families and communities to enable optimal health outcomes” (Schroder et al. 2011, p. 190). The ability to collaborate with other professionals is especially vital in healthcare (Suter et al. 2009), as the incapability to collaborate can negatively impact the care delivered (Zwarenstein et al. 2009). In this respect, a collaborative practice in which different professionals jointly create solutions improves the care delivered (Orchard et al. 2005; Schroder et al. 2011).

In a heterarchical structure, power dynamically shifts from one member to the other, depending on which capabilities are demanded (Aime et al. 2014). By contrast, power relations among care professionals are traditionally rather static and characterized by power inequalities arising from status differences. This creates major difficulties but also opportunities for power dynamics in interprofessional collaboration (D’Amour et al. 2005). Especially in care professions, gaining autonomy is an important step in developing one’s professional status (Engel 1970; Schutzenhofer 1987). A high level of autonomy lowers the likelihood of professionals communicating and sharing authority with other professionals (Kohn et al. 1999; Institute of Medicine 2001). Simultaneously acknowledging the need to collaborate, but wanting to hold on to autonomy and independence, therefore reflects an inherent tension in the collaborative process (Thomson and Perry 2006). That is, autonomy indicates freedom of choice, while collaboration requires a joint solution, meaning the professional’s preferred solutions need to be checked with and possibly adjusted to the rest of the group.

Collaborating necessitates the professionals to jointly exercise power by making themselves heard and joining in decision-making as well as knowing how to share responsibilities and coordinate their activities (D’Amour et al. 2008). Power dynamics can play out in a formal and informal process (Kanter 1993; Laschinger et al. 2004). Through positive social interactions, actors within interorganizational collaboration can gain informal power while the nature of their profession gives them formal power. Informal power may especially be important in creating interorganizational collaborations that result in high-quality care outcomes (Hardy et al. 2003).

To collaborate effectively, professionals need to develop trust among each other (D’Amour et al. 2008). Here, the concept of psychological safety plays an important role in both the collaboration and decision-making processes the professionals take part. That is, the collaborating professionals can be broadly conceived as a team, in that they collaborate for a common goal. We, therefore, draw on Edmondson’s definition of psychological safety as ‘a shared belief that the team [emphasis added] is safe for interpersonal risk-taking’, which suggests ‘a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject, or punish someone for speaking up (Edmondson 1999, p. 354). It appears that trust and respect between the professionals in a team improve when they develop a thorough understanding of each other’s roles and responsibilities (professionals knowing each other’s roles, which avoids care duplication and disputes about territory) (Suter et al. 2009), implying they need to communicate.

Whereas effective communication in interprofessional care collaboration is foremost conceived as the ability of the professionals to negotiate and resolve conflicts and coordinate care as well as use language that fits with the audience (Suter et al. 2009), the most critical aspect of interorganizational communication is the extent to which participants demonstrate the ability to communicate quickly and transparently and thereby signal and repair mistakes at the moment they occur, thereby avoiding major risks and costs (Goodman et al. 2011).

2.2. Resilience in the Interorganizational Context

The extant literature provides some groundwork for this study in the area of interorganizational resilience (e.g., Jung et al. 2019; Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011), interorganizational systems (e.g., Hart and Saunders 1998), and interorganizational reliability (e.g., Rice 2021). The term resilience arose from resource dependency theory, which seeks to understand the organization by viewing it as part of the (social) networks in its environment and dependent on the resources provided by it (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978).

Interorganizational systems have been studied in terms of power dynamics and the level of trust and commitment to the interorganizational relationship (e.g., Hart and Saunders 1998). These studies consider the interorganizational system as a supply chain characterized by power dependencies and subsequent asymmetries (Hart and Saunders 1998) and highlight the necessity of interorganizational relationships and associated social capital in enabling responses to environmental turbulence (Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011).

Rice (2021) extends the literature on high-reliability organizations (e.g., Weick et al. 1999) by referring to high-reliability collaborations. She illustrates how power asymmetry comes forward in communication between the different members of the collaborative. She finds the collaborative decision-making process is influenced by those who claim urgency: certain members of the collaboration claimed power (and were given power by others) by persuading others that their claim was more urgent. Indeed, those able to persuade others to adopt their way of thinking set the tone for the remaining collaboration and influence the collaborative decisions made (Dewulf and Elbers 2018).

Based on this prior work, we argue that the literature on resilience can benefit from considering interorganizational resilience as something that is distinct from the resilience of the individual organizations participating in the collaborative (cf. Jung et al. 2019) or supply chain (cf. Hart and Saunders 1998). Specifically for interprofessional care collaborations, investigated later in this paper, we argue that the resilience of the collaborative entity should be assessed in terms of the relationships among all participating professionals, especially as these are expected to improve communication and serve to eliminate the negative consequences of power asymmetry (cf. Hart and Saunders 1998) and prevent misplaced urgency claims (cf. Rice 2021) and avoid a disproportionate influence on decision-making (Dewulf and Elbers 2018).

The literature on resilience in an interorganizational context thus only partially offers a point of departure. Organizational resilience tends to develop over time (Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011; Ortiz-de-Mandojana and Bansal 2016; Samba and Vera 2013), which suggests it is a dynamic organizational capability that has to be renewed continually (Schreyögg and Kliesch-Eberl 2007). Therefore, organizational designs need to incorporate resilience to be able to dynamically adapt to changing environmental demands (Alberts 2012).

Previous studies have addressed how interorganizational relationships can be regulated (e.g., Thompson 1967; Pfeffer and Salancik 1978) but the existing body of knowledge on how the design of interorganizational collaborations influences their resilience is limited. We can therefore learn here from how the design of a single organizational structure benefits resilience. As such, less hierarchical (i.e., increasingly flat) organizational designs appear to be more resilient than their centralized counterparts (Mosca et al. 2021) because they ensure employees’ autonomy in deciding upon actions (Mallak 1999) and thus enable them to act quickly, based on facts on the ground (Sheffi and Rice 2005). In turn, organizational resilience refers to how well a (collaborative) organization succeeds in overcoming adversity (King et al. 2016) and thus dynamically adapts to the environment. Several key constructs are relevant here: anticipation, adaptation, and thriving.

For one, anticipation involves the prediction and—when necessary—prevention of potential changes ahead of time (Weick et al. 1999). By contrast, adaptation involves dealing with problems as they arise, through error detection and containment (Butler and Gray 2006), which requires the organization to simultaneously identify an environmental cue and know what actions needs to be taken to improve the situation (Freeman et al. 2003).

To define adaptation, we draw on Beermann’s (2011) notion of ‘autonomous adaptation’ taking place at that very moment without deliberate or planned action. Where anticipation implies proactive organizational behavior, we thus conceive of organizational adaptation as being largely reactive in nature (Hrebiniak and Joyce 1985). As such, we build on and add to Hrebiniak and Joyce’s (1985) definition by assuming that organizational adaptation involves reactive responses to both endogenous and exogenous changes.

Spreitzer and Sutcliffe (2007) suggest that organizational thriving is about collective learning and being energized. Collective learning can arise from trying new things, taking risks, learning from mistakes, and building capabilities and competencies from thereon. A collective sense of being energized involves high employee vitality. Moreover, trust appears to enhance both vitality and learning, directly or mediated by connectivity, and therefore is an important enabler of thriving (Spreitzer and Carmeli 2009). That is, individuals that develop trust in their organizations, tend to increase their level of vitality to engage in tasks and develop trust in their employers, enabling learning as they feel support from their employer in taking risks and trying new things. Connectivity here implies that individuals experience relationships with each other in such a way that the influence of the other provides an impetus to learn.

3. Research Method

The main question informing our study, described earlier, is a ‘how’ question that invites an in-depth case study approach (Yin 2006). Moreover, to allow for an initial exploration of the mechanisms and processes in interorganizational collaboration and resilience, we focus on cases that have demonstrated a high level of resilience to avoid the question of “whether or not resilience is high” interfering with the analysis.

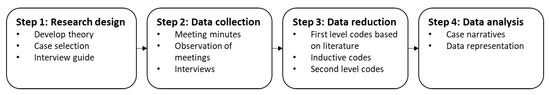

We thus decided to select two cases of interorganizational collaboration in Dutch maternity care, which both successfully dealt with major threats and crises in the past 10 years (incl. major financial cutbacks on maternity care by the Dutch government and the COVID-19 pandemic). The likeliness of their resilience was established upfront by a well-informed expert in the field. By contrast, some other interorganizational collaborations in Dutch maternity care performed less well. For example, in another collaborative the partnering hospital closed, without consultation with the obstetricians, forcing them to take their clients to another hospital located 50 km further away. As a result, this other hospital faced major problems in handling the growing patient flow. Though this is no actual measurement of their lack of resilience, it is a strong indication thereof. By contrast, the two case organizations did not show any such miscommunications or other major turmoil threatening the collaboration, and by extension, their resilience. Appendix A contains a detailed description of the two cases selected. Figure 1 illustrates the case study method of this study.

Figure 1.

Case study method.

3.1. Research Design

In line with Eisenhardt (1989), we are especially interested in the commonalities rather than idiosyncrasies of the two cases studied. In this respect, we follow the primary argument of Eisenhardt that theory development mostly benefits from a comparison of cases across organizational contexts, by obtaining comparative insights but losing contextual insights (Dyer and Wilkins 1991). In our study, this trade-off was addressed by comparing cases within a single context, thereby safeguarding an in-depth understanding of the (e.g., national and industrial) setting. We obtained full access to all relevant data and could assume literal replication (Yin 2006). Though the internal characteristics of the cases are different (see Appendix A), the industrial and institutional background of the two collaborations is similar; therefore, we would expect similar results for each. The case selection also reflects theoretical sampling, because the cases differ in terms of several internal (e.g., decision-making) characteristics; in addition, elements of convenience sampling were also used, by selecting two cases to which we could actually gain access. This combined sampling approach was initiated by the search for two interorganizational collaborations in maternity care that exhibit high resilience. This approach, involving sampling on the dependent variable, is justified because our study is explorative in nature.

3.2. Data Collection

From fall 2019 till summer 2020, the first author collected qualitative data by means of interviews, observations of meetings, consultation of meeting minutes, and other branch-specific documental data that apply to both case A and case B (see Table 1). This triangulation of data served to offset any biases and increase the validity of the results, which also helped discover novel aspects of the phenomenon studied (Dubois and Gadde 2002), such as the underlying conditions and processes giving rise to interorganizational resilience. That is, the presence of some concepts and constructs under study was difficult to establish based only on a single data source. This was the case, for example, when analyzing the data on the more unobtrusive construct of informal empowerment, which is usually difficult to obtain from sources such as documents and instead requires substantiation from data sources providing insight into people’s interactions, such as observations.

Table 1.

Overview of Data Sources.

The observations included face-to-face meetings as well as online meetings (during the COVID-19 pandemic). These participant-observations primarily gave insights into the interactions during the decision-making process, including the type of interactions that led to decisions. While attending face-to-face meetings, the main researcher positioned herself as a ‘fly on the wall’, not actively participating to influence the process as little as possible. These observations of meetings were enhanced by informal conversations prior, to or directly after, the meetings. By contrast, the online meetings required a different approach, especially when the observation of (nonverbal) communication became more difficult through low video quality or simply through weak internet connections. In all online meetings observed, the main researcher announced herself at the start of the meeting, after which she would turn off her camera and microphone.

After the observations were made, the meeting minutes for both cases were explored in more detail. These detailed minutes gave insights into the decision-making process, especially regarding coordination and communication (i.e., transparency, lack of or miscommunication, feedback, announcements, discussions, requests, and propositions). The minutes also shed light on several critical incidents that occurred, both within and outside the VSV/IGO collaboration. We assessed the criticality of incidents based on how often they appeared in the meeting minutes, which were consulted for the entire periods that the two collaborations existed (i.e., since 2012 and 2019, respectively).

Many documents (including government reports) were read and analyzed, providing insights that helped to triangulate various key patterns and critical incidents arising from the observations and meeting minutes. Moreover, various documents provided branch-specific data collected in other studies (Struijs et al. 2016, 2017, 2018), which reinforced the longitudinal nature of the study.

Interviews were held with different organizations and their professionals, such as gynecologists, obstetricians, and representatives of maternity care providers. For case A, the interviewees included one gynecologist, two obstetricians, a maternity care assistance director, and one maternity care assistance manager. Specifically for case B, the interviewees included one gynecologist, three obstetricians, and two managers (one in charge of managing the IGO and the other in charge of managing maternity care assistance in the region). The sampling of these interviewees was intended to represent all main actors in the maternity care collaborations. The sample was, however, limited to those professionals that attended the meetings. This served to obtain exclusive insights into the decision-making process during meetings but did not deliver any insights into the day-to-day collaboration. This was partly offset by asking specifically about daily interactions in the interviews. The interviews gave more detailed insights into critical incidents and how professionals in the two collaboratives experience the collaborative process.

Each interview took around 45 min and was conducted utilizing a semi-structured interview script (see Appendix B for the interview protocol). During the first interviews, the COVID-19 pandemic had already broken out, providing a unique test of collaborative ‘resilience’ because maternity care was, like other types of care, directly impacted by the crisis. COVID-19 was therefore included explicitly in the interview guide. Based on the answers of the interviewees, the pandemic could be identified as a critical incident in both cases. Though both cases entail several other critical incidents in the last decade, we opted to isolate the pandemic as the key crisis studied in this paper; this serves to focus on how the interorganizational collaborations activated their resilience potential in real-time, in response to an extra crisis in an industrial context that had already been exposed to several severe challenges earlier.

3.3. Data Analysis

The various data were analyzed by means of a semi-open coding approach, including a partially deductive coding exercise and an open coding exercise followed by axial and selective coding. The documental data gave rise to relevant codes that describe the context in which the two cases were embedded. Appendix C provides the coding scheme for the main concepts that arose from the data and resulting theoretical constructs.

The coding process comprised several steps which took us from first-level codes informed by the literature on interorganizational/interprofessional collaboration and organizational resilience (i.e., shared decision-making, coordination, shared goals, effective communication, mutual trust and respect, cooperation, psychological safety, conflict management and resilience dimensions of anticipation, adaptation and thriving) to second-order codes of shared vision, interorganizational trust, interorganizational psychological safety).

Some codes did not turn out to be relevant, such as conflict management (i.e., no data were collected indicating the existence of conflicts or the management of it). The code of shared decision-making proved to be better subsumed under the umbrella of adjacent codes such as coordination and effective communication. The code for shared goals appeared to cover mostly data indicating the existence of a shared vision rather than a shared goal. That is, the acts illustrative of the code shared vision are of a non-deliberate nature and were required by the unexpected onset of COVID-19. As such, they did not point to any formerly set goals.

Codes arising inductively from the data consist of interorganizational commitment and interorganizational support, which were, together with interorganizational trust derived from diving deeper into the first-order code of mutual trust and respect. Informal empowerment was also included upfront in the coding process. The coding process was initially performed by the main researcher and then discussed with and checked by the other researchers to ensure the reliability of the data analysis.

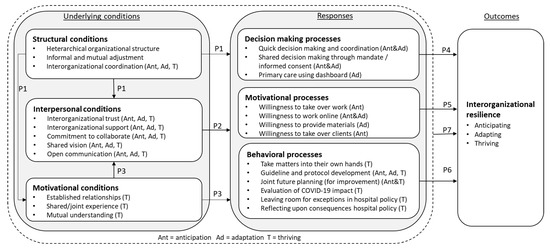

In presenting the data, we followed Eisenhardt and Graebner (2007) by producing a partial narrative in summarizing the data in Appendix D. This appendix presents the data according to the main theoretical constructs (i.e., the interorganizational collaboration and resilience constructs), to show how these are used and thus allow for theory testing. At the same time, we actively pursued theory enhancement by being open to new or improved concepts arising from the data; as such, we combined induction and deduction. Specifically, this meant that the theoretical model in Figure 2 was partly informed by concepts arising from the existing literature (e.g., the structural conditions created by heterarchical organizational designs and mutual coordination, and the resilience dimensions as conceptualized in the background section and partly by concepts arising from the data (e.g., trust, communication, and support). Without compromising the richness of the data from the narrative and Appendix D, we abstracted the data in a model (Figure 2) outlining key conditions and processes for interorganizational resilience as an outcome. The design of the model itself, which categorizes the various concepts as conditions, processes, and outcomes, was also informed by the literature (e.g., Benner and Tushman 2003).

Figure 2.

Conceptual Model.

4. Findings

In this section, we present the main findings of the study in the form of a narrative and a conceptual model.

4.1. How Interorganizational Collaborations in Maternity Care Engaged with the Pandemic

4.1.1. Quick Decision-Making in the Absence of Guidelines and Measures

As of February 2020, maternity care providers in The Netherlands became fully aware of the threat of COVID-19. Both VSV and IGO experienced the same turbulence and dealt with it in somewhat distinct but also highly similar ways. To illustrate this, we first describe the Dutch (maternity care) setting and subsequently how VSV and IGO dealt with the crisis in the period directly before and after the COVID-19 outbreak.

When in February 2020 the news spread that the first Dutch person was infected with the virus, the Dutch population was still largely unaware of what was to come. None the less, professionals in the IGO collaboration already touched upon the impending crisis, by postponing certain planned activities with COVID-19 in the back of their minds: “With regard to Corona, the mini-symposium surrounding retraining in the case of child molestation is being postponed” (Meeting minutes, 14 February 2020). However, mid-February) there were no official announcements yet by the Dutch government concerning COVID-19, nor were there any specific guidelines for maternity care. It was not until 3rd March that the network organization of all Dutch maternity care providers (CPZ) signaled the need for information about measures against the virus. At that time, there was no specific protocol for dealing with the virus yet, so the advice was to follow the flu protocol. Nationwide, the focus was on keeping patients as much as possible out of hospitals, and regional bodies such as ROAZ (i.e., a regional collaborative entity for acute care) were put in charge. Therefore, professionals were advised to contact the ROAZ.

The day before a nation-wide lockdown was announced on Sunday, 15 March, immediate consultation took place amongst the board members of cases A and B, making sure that everyone could do their work as of the next day. For case B, the board (consisting of an obstetrician, gynecologist, hospital representative, maternity care assistance manager, and general manager) already had the mandate to act on behalf of the organizations that were part of this collaboration. In case A, a similar approach was adopted, in the absence of a formal mandate; that is, while all professionals would previously have been asked to give informed consent, some decisions were now (quickly) taken without it.

These agile responses were possible because both collaboratives had already established themselves in such a way that the participating professionals were deeply aware of each other’s viewpoints, to the extent that they knew upfront whether others would agree or not: “By now you know, because you work together for a long time already, like well, probably everyone agrees with this. Here’s consent without having to ask for it” (Obstetrician 1).

In making these initial decisions, the VSV (case A) did not wait for guidelines from the Dutch association for gynecologists (NVOG) and the Dutch association for obstetricians (KNOV) but decided to trust their own judgment. By 16th March, the professional association of maternity care assistants called upon all maternity care collaboratives to appoint a maternity care assistance coordinator responsible for interacting with the coordinator for obstetricians on behalf of all maternity care assistants. On the same day, however, the KNOV announced that obstetricians were to do more consultations by phone and do fewer home visits. The two professional organizations apparently did not (extensively) consult each other, as a maternity care assistance manager observed: “There could have been better coordination of care, if you look at the professional organizations” (Maternity care manager).

4.1.2. Introducing Measures and Guidelines

On 17th March, the NVOG, KNOV, and National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) decided to follow the international RCOG guideline as there was still limited information available on pregnant women and their children regarding COVID-19. Professionals were therefore urged by their professional organizations to notify them when they encountered a client with COVID-19 to help them collect data. By this time, professionals were advised to follow general information provided by the RIVM regarding COVID-19 measures. Primary care providers were recommended to consult with secondary care in the case of a COVID-19 infection or to contact the NVOG. A flowchart was provided to guide professionals in shaping their COVID-19 policy, largely informed by knowledge gained during the earlier outbreaks of SARS and MERS viruses.

On 18th March, the association of maternity care assistants, KNOV, NVOG, and other bodies together called upon professionals to make local agreements, so home-based, as well as hospital-based child births, would be secured. In some regions, obstetricians were not allowed to join their clients in the hospital but instead were forced to completely transfer them to this hospital.

On 19 March, the Dutch association of healthcare insurance companies sent a letter to all care professionals on how they planned to support them, to ensure they would not be unnecessarily burdened with financial insecurity and bureaucracy. In 2019, the South/West region of the Netherlands already developed a dashboard, initially aimed to inform primary care professionals on the availability of delivery rooms in the hospital. The COVID-19 crisis accelerated the further development of this dashboard, to ensure it could be used not only on a local scale but also to show the available capacity of all VSVs and adjoined hospitals in the region. In addition, a regional call center was set up to support all professionals with transferals from within and outside the region.

By 26th March, the dashboard and call center were put into use. One gynecologist in case A reflects on how these systems facilitated the VSV in supporting other organizations and saved them time in making decisions: “And we’ve even helped people from Den Bosch and Breda, because they did not have space anymore or because operating rooms were closed. So, we partly provide care support for people living outside the region. (…) And there we also had a sort of dashboard in which you could see if wards were full or not, so obstetricians knew immediately: oh, it’s no use calling them” (Gynecologist 1).

4.1.3. Ineffective Guidance by National and Regional Organizations

By 31st March, hospitals were still taking care of pregnant women and newborns: the departments for obstetrics and neonatology continued to provide consultations and acute care while being carefully separated from wards with COVID-19 patients. VSVs were urged again to contact the ROAZ and make joint agreements within each VSV in view of different future scenarios, to ensure the region would provide high-quality maternity care.

However, the ROAZ did not manage to properly consult several stakeholders in the field, as its policy measures did not adequately respond to the needs of obstetricians in case A; similarly, collaboration B also observed ROAZ did not adequately respond to their IGO form. That is, the ROAZ was not used for organizations in which both primary and secondary care were represented, and thus it ignored the IGO and instead invited primary and secondary care representatives from elsewhere. This resulted in the case of B initially being excluded from regional policy-making. The IGO in case B, therefore, appointed a coordinator in charge of communication with the ROAZ, which eventually resulted in inclusion in the decision-making process.

Both maternity care collaboratives observed that measures were not coordinated well at the national level and other collaboratives elsewhere appeared to suffer from inadequate coordination between obstetricians and gynecologists. A gynecologist in case A shares the following about this: “I received messages from other VSVs in which the collaboration wasn’t good. During corona, there was no communication whatsoever anymore. The hospital would put stuff on its website which the obstetricians did not know anything about, that they should go to the obstetricians or something. You know? Then, you get crazy things like that” (Gynecologist 1). Overall, the national and regional bodies largely failed to help local professionals in maternity care in dealing with the crisis.

4.1.4. Struggling to Exchange Information

On 6th April, a secured website was made available (by the CareCodex foundation), through which professionals could share client data without any extra costs. Healthcare insurers had decided to temporarily increase the rates for maternity care assistance, as the crisis required extra measures to be taken by these professionals. This temporary increase in rates was only to last from 1 April to 1 July 2020. The insurance companies also expressed the willingness to compensate maternity care providers for missing out on income due to COVID-19.

By 7 April, the government endorsed a crisis law for its decentral bodies, enabling them to temporarily make legal decisions by means of digital meetings (Rijksoverheid 2020). Case B had already met digitally in April before any guidelines specific to maternity care were expressed by the CPZ. By 9th April, the CPZ signaled to the Area Health Authority, the national network for acute care, and the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport, on behalf of all maternity care professionals, that not in all regions a clear overview concerning protective materials was in place. Simultaneously, the Ministry was in search of creative solutions regarding COVID-19 and offered an extra financial incentive for those willing to work on such solutions.

Regarding online meetings, case A was hesitant at first and postponed meetings, but eventually, it held the first digital meeting in June 2020. In case B, the members of the board considered the impact of meeting online as not beneficial to the collaboration, because it would not allow for discussions of highly sensitive topics. By July, both collaboratives had held a physical meeting again, which was possible due to the limited number of participants present. Therefore, both collaboratives showed themselves to be able to adapt to the situation by meeting online. The IGO also started thinking about how to extend the strategy to minimize physical encounters to interactions with clients: “The consequences of the Coronavirus have a big impact on regular care. That’s why it is considered to organize online meetings for vulnerable clients” (Meeting minutes, 14 April 2020).

4.1.5. Handling the Relaxed Measures

Case A did not comply with the guidelines prevailing as of March, as the following quote from an obstetrician in the VSV shows: “In our case, you can just approach the gynecologist when for example this lady does not speak Dutch; it’s formally not allowed to have a third person present at the delivery, but this lady does not speak a word of Dutch, so can her neighbor please come along as an interpreter? And yes, of course, this is better for everyone, instead of only saying, no, that third person is not allowed in” (Obstetrician 1). According to the obstetrician, the fact that the professionals from primary and secondary care are able to freely communicate without considering professional status enables them to come up with solutions that, while not fully complying with national rules, offer the best care for clients in situations such as the one above.

On 8 May 2020, the strict measures were relaxed to the extent that pregnant women’s partners were allowed to be present again during ultrasounds and delivery. Once the relaxation of measures was announced, it became clear the adapted measures were not aligned with the extant policy of certain hospitals, ultrasound centers, and obstetrics practices which were still trying to contain the inflow of patients. For example, in the IGO case, the board members discussed the consequences of the incongruence between the relaxed national guidelines that imply the hospital could still not allow a “plus one” (i.e., an extra family member allowed in the delivery room) and the IGO’s own policy: “Anne [obstetrician] mentions that [the hospital] still does not allow a plus one, which has resulted at least in a substantial number of Turkish women choosing to give birth at home rather than at the hospital. So that’s something to consider, she says to Peter [gynecologist]” (Observation of IGO board meeting, 6 July 2020).

4.1.6. Communication and Support: The Key to Success

The latter observation of how policy incongruences were addressed also illustrates what both the VSV and IGO stressed as the key to their success in responding to the COVID-19 crisis: short communication lines, created by direct and clear communication and coordination between the involved professionals. These short communication lines were already in place before the crisis presented itself. For the VSV, this communication practice (also) arose from the use of sociocracy, which ensures that possible hampering factors were removed: “This way we’ve actually created trust in the decision-making process, through which the general trust had become so large that it eventually very much benefited the collaboration. (…) And then actually with that corona crisis there was a quick coordination in the region. (…) If there were miscommunications, they were eliminated immediately. So it [sociocracy] really paid off, especially the short lines, being able to communicate, no power games or what have you” (Gynecologist 1).

For the IGO (case B), another key factor that may have enabled short communication lines was the fact that all professionals involved acted as one organizational entity. This meant that a single organization (i.e., the IGO), instead of different professionals and their organizations, was accountable for delivering all maternity care services to clients, resulting in the ability to communicate clearly and act quickly: “[…] And the benefit is, because you are one organization, you can all do it the same way and you don’t need to consult with everyone” (Obstetrician 2); “yes, I think the success factor was that you know each other, we’re really just one [emphasis] chain; the success factor was that people were convinced of the fact that the hospital also faced a problem once a COVID patient could not go home because of a lack in protective materials” (Maternity care assistance director).

Moreover, an obstetrician in IGO claimed that obstetricians took over some of the work of the gynecologists to prevent the latter from becoming overworked, based on the idea that they depended on each other in successfully coping with the crisis: “We found ourselves in a very strange situation as maternity care assistants, because we were not part of acute care and obstetricians were. So, the obstetricians could receive protective materials, but we couldn’t. But we were involved in the same delivery if it was a home birth. So, that was a very strange situation. And there were regions where hospitals said: yes, that’s your problem, we cannot help you. And there were ones that said, well we’ll do what we can. But [the hospital here] just said, we’re going to arrange that together. And thus they’ve provided us with protective materials” (Maternity care assistance director).

4.1.7. Reflecting on the First COVID-19 Wave

Over the summer of 2020, the first COVID-19 wave ended. Partly induced by COVID-19, the Dutch government sought to decrease the number of locations where critical care would be provided, while at the same time shifting focus to the prevention of acute care and providing care services closer to home (Ministerie van VWS 2020). This could mean home-based care, but also e-health and remote monitoring. In proposing future plans for acute care (part of which is maternity care), the government demonstrated some level of reflection, recognizing that COVID-19 had put pressure on healthcare provision in its entirety (Ministerie van VWS 2020). The Dutch government pressed ahead on this observation by arguing that healthcare will have to be organized differently and suggested hybrid forms of care, consisting of a mix of physical and digital contacts.

In the IGO case, such reflections were already taking place, as the board members came to realize that because of the crisis, certain practices that were previously impossible now had become possible. Therefore, the IGO board developed a plan to minimize the number of physical maternity visits, as it was found during the crisis that these were not strictly necessary. As such, the IGO collaborative showed the ability to thrive by implicitly reflecting upon the collaboration: COVID-19 was considered an ‘experiment’ that appeared to have strengthened the collaboration.

The VSV also reflected upon the collaboration during the first wave of the pandemic, concluding it went rather well and that the crisis underlined the importance of collaboration. As opposed to the other case, this reflection was an explicit part of board meetings: “Because there was more pressure behind it to arrange it quickly, that very quickly some sort of decision could be made and we did not end up in endless discussions; and that was not the case because everyone felt the urgency that a decision really needed to be made, a consent decision on how to handle certain things” (Obstetrician 1).

These reflections suggest the two cases provide an example of what was being witnessed nationwide: COVID-19 did not only result in fear and insecurity, but it also gave rise to new insights and new solutions. In the care sector, the urgency of the pandemic apparently provided space for breaking free from old patterns and collaborating across disciplines and domains; moreover, conversations about impossibilities shifted to conversations about creativity, flexibility, and solutions (Blokzijl et al. 2020). Both IGO and VSV appear to have made this shift, demonstrating not only the ability to anticipate and adapt but even to thrive in a crisis where other organizations appear to have failed. They accomplished this by knowing how to communicate and coordinate quickly, enabling effective actions at a local level. All of this happened despite the national and regional agencies lagging behind, and, more importantly, failing to synchronize and coordinate their actions and communications with local organizations such as the VSV and IGO. Appendix D provides a chronological overview of key incidents in the case narratives.

4.2. Theoretical Implications

From the narrative and Appendix D, we inferred specific conditions and processes that enhance interorganizational resilience. That is, the responses in both cases can be subdivided into decision-making, motivational and behavioral processes. We also found that the underlying conditions that incite these processes are of a structural, interpersonal, and/or motivational nature and that the interpersonal conditions are facilitated by the other two, and in turn elicit each type of response process. Figure 2 outlines the conceptual model arising from our findings.

The underlying conditions appear to drive the various processes and interorganizational resilience. For example, trust as an interpersonal condition and heterarchy as a structural condition enable the decision-making process in such a way that the collaborative entity can quickly make decisions.

4.3. Propositions Arising from the Conceptual Model

We started this paper by arguing that the structure of an interorganizational collaboration is vital in determining its resilience. While our findings underline this hypothesis, we also observed that interpersonal and motivational conditions—largely prompted by the structural conditions—appear to be pivotal in shaping the potential for resilience. Especially as they together promote behavioral processes that make the interorganizational collaboration go beyond merely performing reasonably well (i.e., anticipating and adapting) to perform and thrive in the face of major changes, that is, to anticipate, adapt and thrive. Each of the seven propositions in the conceptual model in Figure 2 is fleshed out in the remainder of this section. The codes (e.g., B1) in the remainder of this section refer to the codes used in Appendix D.

4.3.1. Proposition 1

Proposition 1: Structural conditions facilitate interpersonal and motivational conditions and promote decision-making and motivational processes. A widespread assumption is that coordination in interorganizational relationships is best facilitated by centralized decision-making (Provan and Milward 1995). However, this study showed that a heterarchical structure, characterized by a non-hierarchical informal collaboration, provides excellent interpersonal and motivational conditions that subsequently shape collaborative decision-making and motivational processes.

The structure of both cases implies no participant in the collaboration has authority over others; thus, all participating organizations and professionals have an equivalent say in the decision-making process. As a result, the traditional hierarchy between care professionals (gynecologist vs. obstetrician) needs to be replaced by interorganizational coordination based on informal and mutual adjustment—which offers an alternative for hierarchical constellations (van Baarle et al. 2021; Clegg et al. 2006). If organizations seek to collaborate effectively, they must therefore recognize they cannot exercise power and control over others and should commit to not exploiting or abusing others when the opportunity to do so presents itself (Todeva and Knoke 2005). Precisely because participants do not have authority over each other, collaboratives need to come up with solutions based on mutual agreement, resulting from dialogue and negotiation (Berkowitz and Bor 2018). As such, in the VSV and IGO collaborations, coordination did not take place in a one-directional fashion; rather, it occurred in dialogue with each other. This enabled swift decision-making in the early days of the pandemic (Appendix D: A1/B2), but also later when primary care had to make quick decisions based on information from the dashboard (A4).

Apart from the impact of structural conditions on decision-making, these conditions also influence motivational conditions. That is, the structural conditions influence the interpersonal conditions, as those conditions could not be instigated or sustained under circumstances of formal, hierarchical conditions. For example, the interorganizational coordination effort between the hospital and the obstetricians, which ensured that no transfer of clients would be needed in the case of outpatient delivery, increased their commitment and trust in the collaboration (Gulati et al. 2012). Indeed, in a study of temporary interorganizational collaborations that did not involve the upfront appointment of a leader, Beck and Plowman (2014) found trust and identity succeeded rather than preceded collaborative actions.

Finally, positive motivational processes can only occur if professionals are structurally enabled to coordinate work. These motivational processes indicate a willingness on behalf of the professionals to do something for each other, which might have implications for the power balance in the collaborative entity. Specifically, the apparent need of one professional can be addressed by exploiting another professional and thus abusing power (Todeva and Knoke 2005). This was, by no means, the case in the collaboratives studied in this paper. The professionals acknowledged and appreciated the advantageous position of the other parties. In that regard, our findings align with Aime et al. (2014): that is, the heterarchical structures of the two collaboratives enabled the various participants to perceive such ‘shifts in power’ as highly legitimate and allowed them to be creative in dealing with the challenges faced (e.g., taking over clients from others).

4.3.2. Proposition 2

Proposition 2: Interpersonal conditions promote decision-making, motivational and behavioral processes and enable all resilience-related processes. The VSV and IGO cases share a strong commitment to delivering the best possible care to their clients. This distinguishes them from other types of interorganizational collaboration in which individual engagement often is optional (Chesley and D’Avella 2020). However, the various participants’ perceptions of how to practically achieve the best possible care may not align initially: healthcare professionals have similar backgrounds but may still fail to establish common ground, due to misinterpretations and different expectations (Wu 2018). Traditionally, collaborative relationships between individual professionals in maternity care are based on hierarchical patterns, which may impede the development of trust. In turn, creating and developing trust among organizations in an interorganizational collaboration can be rather challenging, precisely because the traditional hierarchy is missing (Ring 1997). As trusting the other party is witnessed as a risky endeavor, participants often revert to power acts to achieve coordination (Hardy et al. 1998). However, this hierarchical power play was not present in the VSV and IGO cases, and as such, mutual trust was already there. Over the years, the interplay between new structural and motivational conditions gave rise to a virtuous cycle of interorganizational trust in both the collaborative work and decision-making process: interorganizational trust facilitated negotiations, reduced conflicts, and as such enabled shared decision-making, eventually leading to improved performance (Zaheer et al. 1998). This virtuous cycle shows such decisions among maternity care professionals are based on straightforward and open discussions, positively impacting not only the decision-making process but also the collaboration itself.

Trust in the collaboration and decision-making process appears to eventually enable the decision-making, motivational and behavioral processes, and in turn, give rise to anticipation and adaptation, but mostly thriving. According to (Spreitzer and Carmeli 2009), trust at the individual employee level does indeed appear to increase vitality and learning. However, when looking at interorganizational collaborations, such trust does not pertain to the individual organization or one’s employer, but to the interorganizational collaboration and the organizations that are part of it. For example, we saw that trust stimulated professionals in both cases to jointly come up with solutions to the COVID-19 crisis, and hand over the decision-making authority to a selective part of the collaborative, knowing that the stakes of the individual organizations were safeguarded nonetheless (A1/B2). The results from the case study also suggest there was substantial trust in developing protocols and guidelines together, rather than trusting in those devised elsewhere (A3/B4). Indeed, trust is vital for collaborative knowledge creation and dissemination (Newell and Swan 2000). Another example is the trust between hospitals and obstetricians, the first allowing the second to operate on her grounds, while national COVID-19 regulations advised otherwise (B5). We also witnessed trust in daring to communicate openly amongst each other about how the entire period went and what could possibly be learned from it for the future (A9/B11).

These examples of acting on trust especially point to the experience of connectivity, as the collaboration stimulated the professionals to be open to each other’s input. Apparently, it felt ‘safe enough’ for the professionals to open up (Edmondson 1999). Building on Edmondson and Roloff’s work on team collaborations, such collective psychological safety is vital to collaborative learning and performance under turbulent circumstances (van den Berg et al. 2021; Edmondson and Roloff 2009).

Moreover, trust appeared to motivate the various professionals to actively engage in collaboration and give them the feeling of being supported by others, in turn increasing the collective level of vitality and learning. This interorganizational support is evident most distinctively from the interview data, in terms of primary and secondary care professionals providing each other with materials, thinking along with each other, and helping each other out when the workload is high. For example, the hospital proved itself to be lenient in the case of outpatient deliveries (B5) and taking care of clients of other hospitals (A4). The hospital, as a member of the collaborative, decided to provide the obstetricians and maternity care assistants with materials (A2/B3). This resonates well with Berkowitz and Bor (2018), who argue that when members of a collaborative organization are themselves in control of the resources, decisions are made in a more horizontal manner. Such learning behaviors (e.g., taking over work, thinking along) and conditions (i.e., trust and support) encourage collective learning and enhance collaborative work (cf. Tsasis et al. 2013).

What characterizes the importance of a shared vision at an interorganizational level, rather than within an organization, is the collaborative effort in creating the vision together (Chesley and D’Avella 2020). Over the years, both collaborations have actively done so. The shared protocol development (A3/B4) and the development of plans for future care provision (B9,11) in Appendix D illustrate such a shared vision. Shared vision and goals in a collaborative effort effectively reduce tensions (Sherif 1958), which arguably has a positive effect on other interpersonal conditions. Having a shared vision also positively affects commitment, as no one would make the effort to jointly write protocols if they were not adamant to make the collaboration work. The high level of commitment can also be inferred from the willingness to meet online (A6/B7), daring to own up to what went wrong (A8/B8,10), and deliberate efforts to learn from the crisis (A6–9/B8,10,11). In turn, these factors point to open communication, perhaps most strikingly reflected in the incident in which the hospital is willing to leave room for exceptions to COVID-19 regulations (A7). Open communication can also be observed in the acknowledgment of what went wrong (A8/B8,10) and the (explicit) evaluation of the first COVID-19 wave (A9).

The interpersonal conditions appear to be mutually reinforcing each other, as communication supports the co-creation of vision and the building of commitment and trust (Chesley and D’Avella 2020). Open communication, spurred by the presence of trust and cooperativeness, can benefit the interorganizational coordination efforts (P1), in turn encouraging the participants to (further) commit to the collaboration, thereby increasing trust even more (Gulati et al. 2012). Overall, the shared nature of the two cases improved coordination activity, because the conditions described by Gulati et al. (2012) were present. All these interpersonal conditions together appear to fuel the resilience of each of the two collaboratives.

4.3.3. Proposition 3

Proposition 3: Motivational conditions facilitate interpersonal conditions, promote motivational and behavioral processes, and enable thriving. By collaborating closely based on commitment and stimulated by governmental guidelines, the connections in both cases strengthened over time, resulting in a shared understanding and experience of the crisis and its consequences for the collaborative. By experiencing hardship, collaborative relationships tend to strengthen over time, creating a ‘collective willingness to collaborate’ across the organization (Hernandez et al. 2020, p. 150). The VSV and IGO collaborative experienced such hardship, not only through the COVID-19 crisis itself but also indirectly through the inadequate performance of for example the ROAZ, giving rise to a joint experience of distrust toward the ROAZ (A5/B6). This distrust might arise from asymmetrical power relations and conflicting interests between the two collaboratives and an organization such as the ROAZ, suggesting a low level of involvement in the broader interorganizational network (cf. Hardy et al. 2003). Both cases also illustrate how close relationships result in a shared understanding, for example regarding the hospital and its willingness to think along and understand the needs of obstetricians, simply by allowing them to enter the hospital during outpatient deliveries (B5) or even allowing a 3rd person in the delivery room when the obstetrician acknowledged the need for it (A7).

All in all, the two cases illustrate how a joint experience of hardship, combined with the acknowledgment of strong interdependence, creates a collective willingness to collaborate. The fact that the motivational conditions promoted the above processes may link back to the facilitation of interpersonal conditions: for example, the establishment of collaborative relations, mutual understanding, and a shared experience enabled the trust to develop over time. The presence of trust at the start of each collaboration, combined with its reinforcement over time, ensured both cases were more than able to face the challenge of COVID-19. Another illustration hereof is the shared experience of distrust in a failing ROAZ having a catalyzing effect on the mutual trust between the partners in the collaboration (A5/B6). The fact that motivational conditions facilitated the interpersonal conditions can also be witnessed from the hospital’s trust and support toward primary care. The outpatient delivery (B5), the extra person in the room (A7), and open communication in discussing hospital policy (B8) all result from previously established relationships and mutual understanding.

4.3.4. Proposition 4

Proposition 4: Shared decision-making processes enable anticipation and adaptation. This proposition directly aligns with proposition 1, in that structural interorganizational conditions promote interorganizational decision-making processes. By design, any collaborative organization has the potential to evoke tensions, as its member organizations exhibit more diversity than individuals—each having its own identity, mission, and tensions to begin with (Brès et al. 2018). In the VSV and IGO cases, we did not observe major tensions, arguably due to a certain relaxation built into their decision-making processes. For example, the very first incident had to be addressed very quickly by both cases, because they could not afford to lose time. Here, the decision-making process adopted (either based on informed consent or a mandate to the board) implied all voices were heard and represented in the process, enabling the collaboration to immediately take a decision (A1/B2). As such, both interorganizational collaborations appeared to be in a more favorable position than most other maternity care collaborations, as the one cost associated with interorganizational cooperation—losing decision-making autonomy—had been eliminated (Schermerhorn 1975). At the same time, the first incident implied an overall adaptation to the COVID-19 crisis itself, as the sudden nature and rapid manifestation of the virus precluded any form of preparedness.

The fact that the VSV was able to quickly come up with solutions, once COVID-19 arrived, was for a large part attributed to the sociocratic decision-making structure. Like obstetrician 1 observed (see narrative), time spent on discussing the actual implementation of decisions during COVID-19 was limited; and commitment had already been obtained during the years before, when decisions had been repeatedly taken by means of the informed consent principle (Romme 2016; Romme and Endenburg 2006), creating a mutual understanding of each other’s stances. Eventually, this enabled the collaboration to focus on what actions needed to be taken to handle the first COVID-19 threat. The fact that commitment was already established also meant that more time and attention could be spent on activities ensuring future performance (Romme 2019). Likewise, decision-making based on a mandate (in case B) resolves any issues over power differences, because the mandate has been created and given (to the management of the collaborative entity) by all members of the collaboration (Hall et al. 1977). The fact that decision-making rules (e.g., how decisions are to be made) were specified upfront, ensured the influence of all actors on the collective decisions made (Dewulf and Elbers 2018).

While both decision-making processes are formalized to a certain extent, the execution of shared decisions is characterized by informal communication and collaboration, indicating informal empowerment. For instance, the various partners in the collaboration operated as equals in serving clients, regardless of any traditional status differences (e.g., between gynecologist and obstetrician). The fact that both collaborations operated in a highly informal manner also exemplifies the pre-existing trust between the partners in the collaboration (Gulati and Nickerson 2008). Another telling example of shared decision-making is the dashboard, provided by a regional body (A4): due to the heterarchical nature of the collaboration, obstetricians were allowed to act on the data provided by the dashboard and adjust their decisions and actions accordingly. Indeed, the obstetricians retained their professional autonomy and were not held back by rules and procedures otherwise prevailing in hospitals. Under more formalized circumstances, their autonomy would probably have been undermined, ultimately jeopardizing their commitment (Organ and Greene 1981).

4.3.5. Proposition 5

Proposition 5: Motivational processes enable anticipation and adaptation. Motivational processes are the only ones prompted by all types of conditions, thereby requiring stimuli from all three process types. The motivational processes pertain to the willingness to take over work (B3), to meet online (A6/B7), to provide materials (A2/B3), and a willingness to take over clients from partners in the collaboration (A4). The IGO appeared to be more proactive than the VSV, for example regarding online meetings: Case B did not sit and wait for regulations to guide their response or for the crisis to blow over, but immediately engaged in analyzing the COVID crisis and developing response scenarios. Case A proved to be more hesitant at first and eventually adapted to the new challenges. Whether more anticipatory or adaptive in nature, the actions taken by both collaboratives point at the partners’ commitment and willingness to reciprocate, thereby strengthening and widening the collaboration (Zaheer and Venkatraman 1995) and enhancing its resilience. This type of ‘network citizenship’ behavior (Provan et al. 2018) is beneficial to collaboration, but not necessarily also to the individual professionals and their organizations.

4.3.6. Proposition 6

Proposition 6: Behavioral processes enable all dimensions of interorganizational resilience, especially thriving. Both collaboratives demonstrated the capability to move beyond doing what was necessary and act outside the box. This included taking matters into their own hands when ROAZ failed to meet their needs. The general approach adopted in case A was more one of shirking the governmental rules and trusting the partners’ own good judgment to do what is right. Case B did try to comply with the rules. The best example of this is when ROAZ did not consult any local maternity care collaborations (as such inhibiting multidirectional information flow and learning; see Hardy et al. 2003): subsequently, case A decided to follow its own path, while case B still sought to be included in ROAZ’s decision-making (A5/B6). In this respect, the VSV in case A was tried and tested when it comes to dealing with setbacks; this collaboration had already lowered its trust in national and regional agencies in the years before. By contrast, the relatively young IGO collaborative in case B was still eager to comply. Thinking and acting outside the box also incorporated active development of guidelines and protocols (A3/B4); adapting to the fact that national and regional agencies did not yet have guidelines or protocols available and anticipating future developments regarding meeting online and the set-up of house visits (A6/B9). Both collaborations also moved beyond what was necessary when the hospital in case B gave obstetricians room for outpatient deliveries (B5) and the hospital in case A relaxed the rules imposed by the government (A7).

The resilience of both collaborations during the COVID-19 crisis did not only arise from the way they collaborated, but also from the way they experienced the situation at hand and actively reflected on this experience. According to Simonin (1997), experience alone does not ensure that an organization benefits from collaboration, rather it needs to internalize this experience in such a way that it can steer future activities. Both collaborations indeed did this, when they reflected on what COVID-19 implied for the collaborative work, such as a change in communication (B10), the implications of online meetings (A6), and the consequences of a strict hospital policy (B8). These reflections elicited joint efforts to improve various work processes (B9,11). Here, especially the IGO collaborative moved beyond mere decision-making to collective sense-making and developing the path forward (Weick 1993).

The ability of both collaborations to accomplish such collective sense-making arises from the collective capability to synchronize visions and focus on a shared goal (e.g., Kennedy et al. 2019): providing the best possible maternity care. For the VSV case, this synchronization process was also enhanced by the informed consent approach to decision-making, which enables the partners to acknowledge and understand each other in the way arguments are formulated and exchanged. Overall, our data suggest that the development of a resilient interorganizational collaboration may require continual learning and adapting, by regularly evaluating and adjusting the collaborative path (Berends and Sydow 2019). As such, one can argue that the two collaboration cases studied here demonstrate huge potential for thriving by design.

4.3.7. Proposition 7

Proposition 7: Interorganizational resilience is (largely) determined by the interplay between conditions and processes. In the Background section, we defined interorganizational resilience as the collaboration’s capability to anticipate, adapt and thrive, thus extending the organizational and intrapersonal dimensions of resilience to the interorganizational level. This extension of the conventional definition of resilience resonates with, for example, Stoverink et al. (2020) who built on Weick’s (1993) theory of organizational resilience to come up with antecedents for team resilience. The fact that the construct of interorganizational resilience remains largely underdeveloped in the literature informed our, at first sight, somewhat careless extrapolation. For now, interorganizational resilience is conceived as “the ability to adapt to challenging and unexpected conditions, while continuing to collaborate interdependently to address wicked issues that cannot be solved by one organization alone” (Chesley and D’Avella 2020, p. 300). Through extrapolating findings from the intra-organizational to the interorganizational level, Chesley and D’Avella (2020) conclude that commitment, vision, adaptation, relationships, and the significance of an issue are important determinants of interorganizational resilience. Our study aligns with these findings, to the extent that commitment, vision and relationships indeed appear to be important underlying conditions for interorganizational resilience and its enabling processes; moreover, we made a preliminary categorization of these conditions and processes and theorized about their connections. Adaptation clearly is an important dimension of interorganizational resilience in both cases, though often in combination with anticipation and thriving. Whereas the focus of the study by Stoverink et al. (2020) was on team resilience, its results support our analysis of resilience at the interorganizational level. By equating interorganizational with team resilience, interorganizational collaboration operates in highly similar ways to teamwork (Solansky et al. 2014).

At the organizational level, resilience apparently requires leadership for its insurance (Chesley and D’Avella 2020; Stoverink et al. 2020), assuming that organizational members are interdependent but depend on managers to deal with major turbulence. By contrast, such leadership does not (ex ante) exist in interorganizational collaboration and, therefore, participants rely much more on each other for their collective performance and resilience. While the common wisdom is that a lack of leadership is problematic for interorganizational resilience, our findings suggest that a single leader is not necessary for a resilient collaboration, but only if its structural conditions and decision-making processes enable shared decisions on all key challenges—also in the face of adversity.

4.4. Contributions

With this study, we aimed to find out how the structure of an interorganizational collaboration determines its resilience. To that end, we obtained preliminary insights into how structural conditions influence and interact with interpersonal and motivational conditions and how this interplay results in certain processes that enable resilience. The propositions describing this interplay serve as the main theoretical contribution of this study; these propositions can also guide and inform future research in this area. They especially imply the necessity of a broader focus on organizational theory, to not only consider the question of how the structure of an organization can be aligned with its objectives in terms of coordination, but also the ‘softer’ question of how people’s motivations and interactions can be optimized in such a way that they ensure the interorganizational collaboration’s design works out effectively.

This study also serves to further conceptualize interorganizational resilience by explicating how it resembles, but also is distinct from, organizational resilience. By witnessing how resilience played out in an interorganizational context, we observed that it appears to be more similar to team resilience than organizational resilience (Stoverink et al. 2020). However, interorganizational resilience and team resilience constitute distinct conceptualizations of the resilience construct: interorganizational collaborations face different, often farther-reaching challenges than intra-organizational teams, also regarding the absence of hierarchy and its implications for trust building (Ring 1997) and the likelihood of power abuse (Hardy et al. 1998). The quest to overcome these challenges calls for more research into how resilience can be developed at the interorganizational level.

We also contribute to the literature by further developing the dimensions of resilience, especially the underdeveloped dimension of thriving (Spreitzer and Sutcliffe 2007; Walumbwa et al. 2018). Thriving may be the dimension that sets resilience apart from mere performance but is, thus far, mainly conceptualized at the individual instead of (inter)organizational level. Our empirical findings suggest that thriving largely arises from interpersonal and motivational (rather than structural) conditions and that behavioral processes are the most distinctive result. However, thriving does draw on structural conditions, especially the heterarchical nature of decision-making on collaborative challenges. This suggests that designing for interorganizational resilience foremost needs to lead to structures that enable people in the collaboration to create positive interpersonal and motivational conditions that enable them to display conducive behaviors. The empirical findings appear to underline the suggestion that thriving distinguishes resilience from performance. Learning, being a key feature of thriving, has been marked as an important area of research, especially in terms of how care professionals learn in the delivery of care (Tsasis et al. 2013). In that respect, the current study has shed light on the impact of interaction, feedback, and reflection on the collective learning and collaboration of professionals in the maternity care context.

Finally, we also contribute to the literature on interorganizational collaboration, which seeks to establish whether an interorganizational relationship is worth pursuing in the first place (Barringer and Harrison 2000). Here, maternity care involves interorganizational cooperation that is not optional, but mandatory: all participating organizations are indispensable links in the larger network of maternity care. What drives interorganizational relationships in health care settings such as maternity care and how they can be sustained, is viewed differently among scholars and practitioners (Palumbo et al. 2020). This empirical setting thereby provides both an exemplifying and a novel perspective on interorganizational collaborations that operate on the cutting edge of voluntariness and rules imposed by government but are also exposed to both formal interactions (induced by medical rules) and informal ones (induced by interpersonal relationships between the professionals). Specifically, the empirical setting of case B can offer relevant insights that can inform similar forms of interorganizational collaboration in other western countries in which funding reforms of maternity care are being implemented (Struijs et al. 2017).

4.5. Limitations and Future Research Paths

While the findings arising from this study are highly interesting, we must be cautious in claiming generalizability. That is, the empirical part of this study is highly contextualized in both geography (i.e., Netherlands) and sector (i.e., care).