The Nefarious Hierarchy: An Alternative New Theory of the Firm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definition of Terms

2.2. Related Literature

3. A New Theory of the Firm

3.1. Doing Social Harm (by Exploiting Market Failures)

3.2. Addressing TotF Requirement #1: Explaining Why the Firm Form is Better

3.2.1. Lower Costs

3.2.2. Lower Risks

3.2.3. Higher Benefits

3.3. Addressing TotF Requirement #2: Explaining Why the (Bad) Firm Is Limited in Growth

4. Results

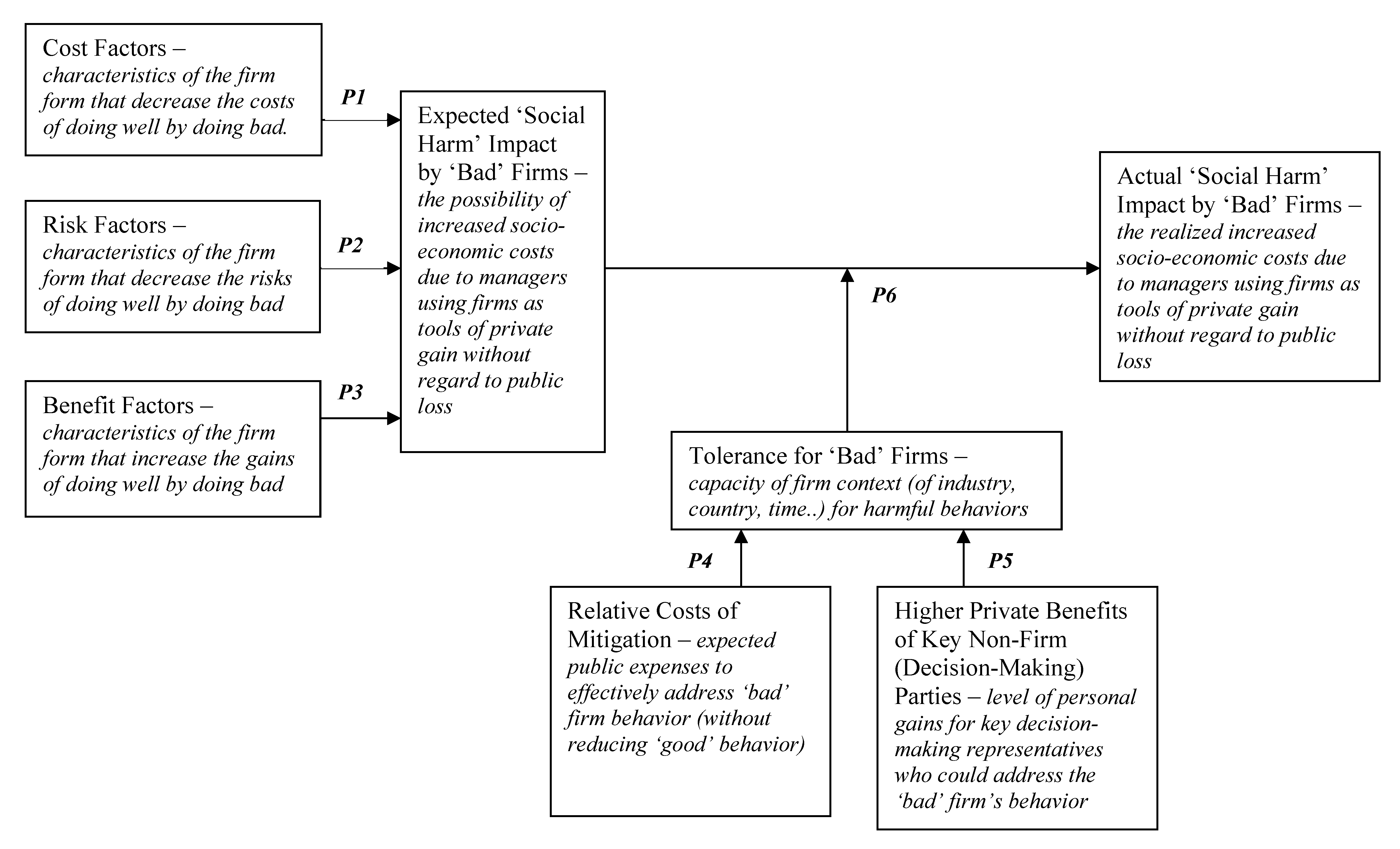

Propositions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akerlof, George A. 1970. The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. Quarterly Journal of Economics 84: 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchian, Armen A., and Harold Demsetz. 1972. Production, information costs, and economic organization. The American Economic Review 62: 777–95. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shammari, Marwan, Abdul Rasheed, and Hussam A. Al-Shammari. 2019. CEO narcissism and corporate social responsibility: Does CEO narcissism affect CSR focus? Journal of Business Research 104: 106–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, Richard J. 2006. SME–supplier alliance activity in manufacturing: Contingent benefits and perceptions. Strategic Management Journal 27: 741–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, Richard J. 2015. Wicked Entrepreneurship: Defining the Basics of Entreponerology. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Argandoña, Antonio. 1998. The stakeholder theory and the common good. Journal of Business Ethics 17: 1093–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, Mehrnaz, Gregory M. Magnan, Michelle Adams, and Tony R. Walker. 2020. Understanding the conceptual evolutionary path and theoretical underpinnings of corporate social responsibility and corporate sustainability. Sustainability 12: 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, Joe S. 1951. Relation of profit rate to industry concentration: American manufacturing, 1936–1940. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 65: 293–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, Joe S. 1954. Economies of scale, concentration, and the condition of entry in twenty manufacturing industries. The American Economic Review 44: 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, George P., Rachna Shah, and Karen Donohue. 2018. The decision to recall: A behavioral investigation in the medical device industry. Journal of Operations Management 62: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baucus, Melissa S., and Cheryl R. Mitteness. 2016. Crowdfrauding: Avoiding Ponzi entrepreneurs when investing in new ventures. Business Horizons 59: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, William J. 1990. Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive. Journal of Political Economy 98: 893–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Ye, Hoje Jo, and Carrie Pan. 2012. Doing well while doing bad? CSR in controversial industry sectors. Journal of Business Ethics 108: 467–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jeffrey, Yuan Ding, Cédric Lesage, and Hervé Stolowy. 2012. Corporate fraud and managers’ behavior: Evidence from the press. In Entrepreneurship, Governance and Ethics. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 271–315. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, Brian L., Laszlo Tihanyi, S. Trevis Certo, and Michael A. Hitt. 2010. Marching to the beat of different drummers: The influence of institutional owners on competitive actions. Academy of Management Journal 53: 723–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, Kathleen R. 1991. A historical comparison of resource-based theory and five schools of thought within industrial organization economics: Do we have a new theory of the firm? Journal of Management 17: 121–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressey, Donald Ray. 1973. Other People’s Money. Montclair: Patterson Smith. [Google Scholar]

- Cyert, Richard M., and James G. March. 1963. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Bó, Ernesto. 2006. Regulatory capture: A review. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 22: 203–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, Michelle K., Daniel C. Ganster, Jason D. Shaw, Jonathan L. Johnson, and Milan Pagon. 2006. The social context of undermining behavior at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 101: 105–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elert, Niklas, and Magnus Henrekson. 2016. Evasive entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics 47: 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Sanchez, Isabel-Maria, Beatriz Cuadrado-Ballesteros, and Cindy Sepulveda. 2014. Does media pressure moderate CSR disclosures by external directors? Management Decision 52: 1014–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, Tiffany, and Katy Jacob. 2009. Payments Fraud: Perception Versus Reality—A conference summary. Economic Perspectives 33: 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal, Sumantra. 2005. Bad Management Theories Are Destroying Good Management Practices. Academy of Management Learning & Education 4: 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Robert M. 1996. Towards a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal 17: 109–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Joseph. 2014. Morality, Competition, and the Firm: The Market Failures Approach to Business Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hmieleski, Keith M., and Daniel A. Lerner. 2016. The dark triad and nascent entrepreneurship: An examination of unproductive versus productive entrepreneurial motives. Journal of Small Business Management 54: 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmstrom, Bengt R., and Jean Tirole. 1989. The theory of the firm. Handbook of Industrial Organization 1: 61–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kini, Omesh, and Ryan Williams. 2012. Tournament incentives, firm risk, and corporate policies. Journal of Financial Economics 103: 350–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirzner, Israel M. 2009. The alert and creative entrepreneur: A clarification. Small Business Economics 32: 145–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, Donald, and Nathan T. Washburn. 2012. Understanding attributions of corporate social irresponsibility. Academy of Management Review 37: 300–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, Steven D., and Sudhir Alladi Venkatesh. 2000. An economic analysis of a drug-selling gang’s finances. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115: 755–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Michael. 2015. Flash Boys: Cracking the Money Code. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Elizabeth N. K., and Brian T. McCann. 2013. Performance Feedback and Firm Risk Taking: The Moderating Effects of CEO and Outside Director Stock Options. Organization Science 25: 262–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelace, Jeffrey B., Jonathan Bundy, Donald C. Hambrick, and Timothy G. Pollock. 2018. The Shackles of CEO Celebrity: Sociocognitive and Behavioral Role Constraints on “Star” Leaders. Academy of Management Review 43: 419–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, David S., and Caleb S. Fuller. 2017. Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive—Relative to what? Journal of Business Venturing Insights 7: 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G. Tom, and Gregory G. Dess. 1996. Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking it to Performance. Academy of Management Review 21: 135–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundmark, Erik, and Alf Westelius. 2019. Antisocial entrepreneurship: Conceptual foundations and a research agenda. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 11: e00104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, Johanna, and Ernesto Noboa. 2006. Social entrepreneurship: How intentions to create a social venture are formed. In Social Entrepreneurship. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 121–35. [Google Scholar]

- Matten, Dirk, Andrew Crane, and Wendy Chapple. 2003. Behind the mask: Revealing the true face of corporate citizenship. Journal of Business Ethics 45: 109–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthiesen, Marie-Louise, and Astrid Juliane Salzmann. 2017. Corporate social responsibility and firms’ cost of equity: How does culture matter? Cross Cultural and Strategic Management 24: 105–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, Abagail, and Donald Siegel. 2001. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review 26: 117–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, Giovanna, Silvia Pilonato, and Federica Ricceri. 2015. CSR reporting practices and the quality of disclosure: An empirical analysis. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 33: 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miska, Christof, Günter K. Stahl, and Matthias Fuchs. 2018. The moderating role of context in determining unethical managerial behavior: A case survey. Journal of Business Ethics 153: 793–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, Sucheta, and Pamela S. Barr. 2008. Environmental context, managerial cognition, and strategic action: An integrated view. Strategic Management Journal 29: 1395–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, Clare. 2014. Report: Walmart workers cost taxpayers $6.2 billion in public assistance. Forbes, April 15. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Hannah, John Bae, and Sang-Joon Kim. 2017. Can sinful firms benefit from advertising their CSR efforts? Adverse effect of advertising sinful firms’ CSR engagements on firm performance. Journal of Business Ethics 143: 643–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orts, Eric W. 1998. Shirking and sharking: A legal theory of the firm. Yale Law and Policy Review 16: 265–329. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, Kalpana, and Thomas D. Tolleson. 2012. The capture of government regulators by the big 4 accounting firms: Some evidence. Journal of Applied Business and Economics 13: 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Donald, Royston Greenwood, and Kristin Smith-Crowe. 2016. Organizational Wrongdoing: Key Perspectives and New Directions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petrenko, Oleg V., Federico Aime, Jason Ridge, and Aaron Hill. 2016. Corporate social responsibility or CEO narcissism? CSR motivations and organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal 37: 262–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Michael E., and Mark R. Kramer. 2006. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review 84: 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rawley, Evan, and Timothy S. Simcoe. 2010. Diversification, diseconomies of scope, and vertical contracting: Evidence from the taxicab industry. Management Science 56: 1534–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehg, Michael T., Marcia P. Miceli, Janet P. Near, and James R. Van Scotter. 2008. Antecedents and outcomes of retaliation against whistleblowers: Gender differences and power relationships. Organization Science 19: 221–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogelj, Joeri, David L. McCollum, Andy Reisinger, Malte Meinshausen, and Keywan Riahi. 2013. Probabilistic cost estimates for climate change mitigation. Nature 493: 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1934. The Theory of Economic Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, David J. 1986. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy 15: 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirole, Jean. 1988. The Theory of Industrial Organization. Boston: MIT press. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, Justin W., Laszlo Tihanyi, R. Duane Ireland, and David G. Sirmon. 2009. You say illegal, I say legitimate: Entrepreneurship in the informal economy. Academy of Management Review 34: 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, Birger. 1984. A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal 5: 171–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Oliver E. 1979. Transaction-cost economics: The governance of contractual relations. Journal of Law and Economics 22: 233–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Shaker A., and Mike Wright. 2016. Understanding the social role of entrepreneurship. Journal of Management Studies 53: 610–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exacerbating Negative Externalities (Not Paying the Full Cost of the Product) More Than Other Firms |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Size-related: the firm form (e.g., as a hierarchy of authority-based-controlled, coordinated specialists with long-term buy-in, shared access to specialized assets, risk-sharing, repetition) can achieve greater size and diversity more efficiently and effectively than a set of spot market contracts:

|

Central Authority-related: the firm form (e.g., as a set of long-term contracts where residual rights are held by the firm, and coordination comes from firm-authorized directions rather than negotiations) can achieve tighter coordination, consistency, and complexity and loyalty than a set of spot market contracts:

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arend, R.J. The Nefarious Hierarchy: An Alternative New Theory of the Firm. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010021

Arend RJ. The Nefarious Hierarchy: An Alternative New Theory of the Firm. Administrative Sciences. 2021; 11(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleArend, Richard J. 2021. "The Nefarious Hierarchy: An Alternative New Theory of the Firm" Administrative Sciences 11, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010021

APA StyleArend, R. J. (2021). The Nefarious Hierarchy: An Alternative New Theory of the Firm. Administrative Sciences, 11(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010021