An Approach to Quality Control of the Dithiothreitol (DTT) Assay for the Determination of Oxidative Potential of Atmospheric Particulate Matter

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

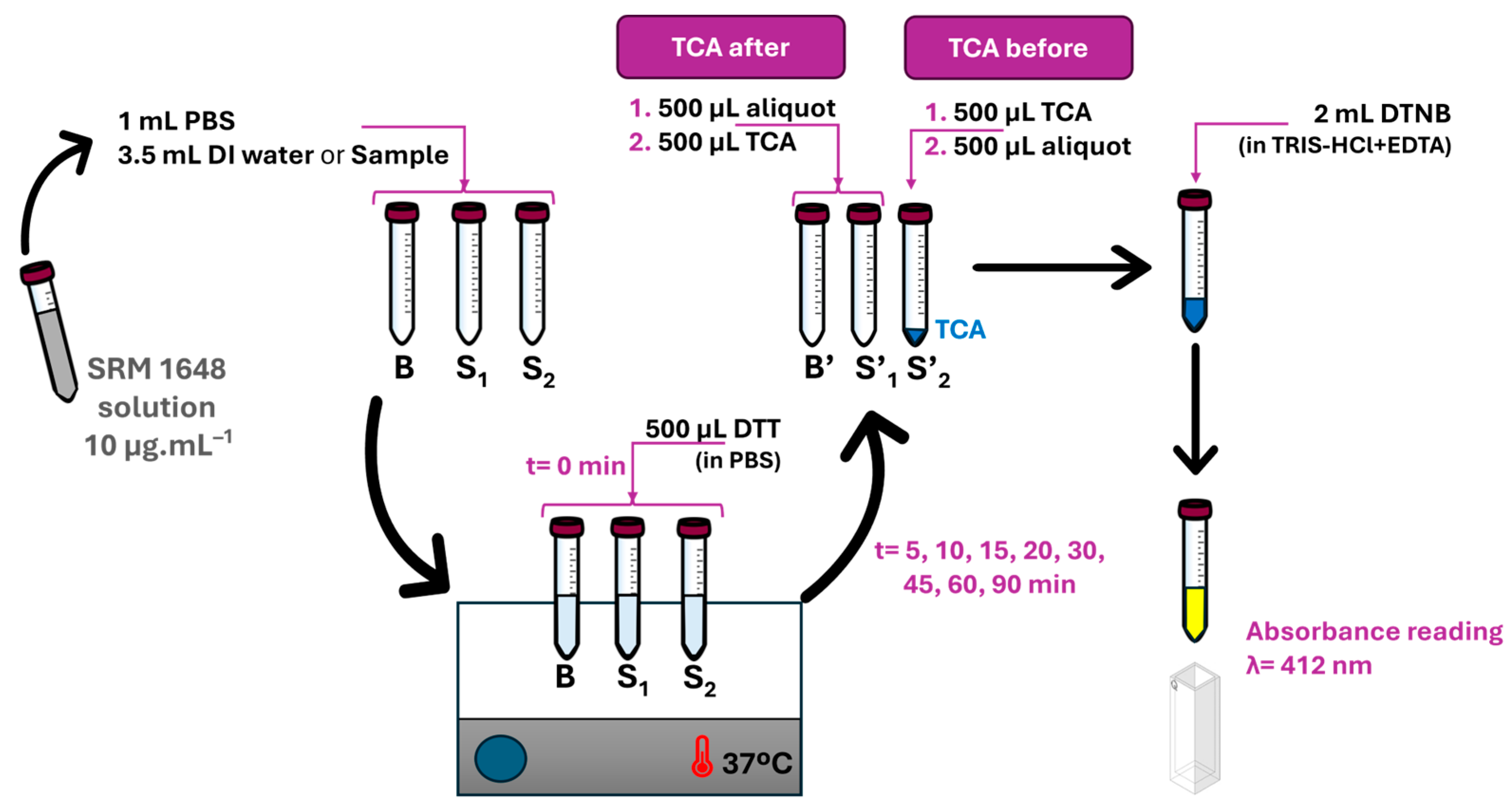

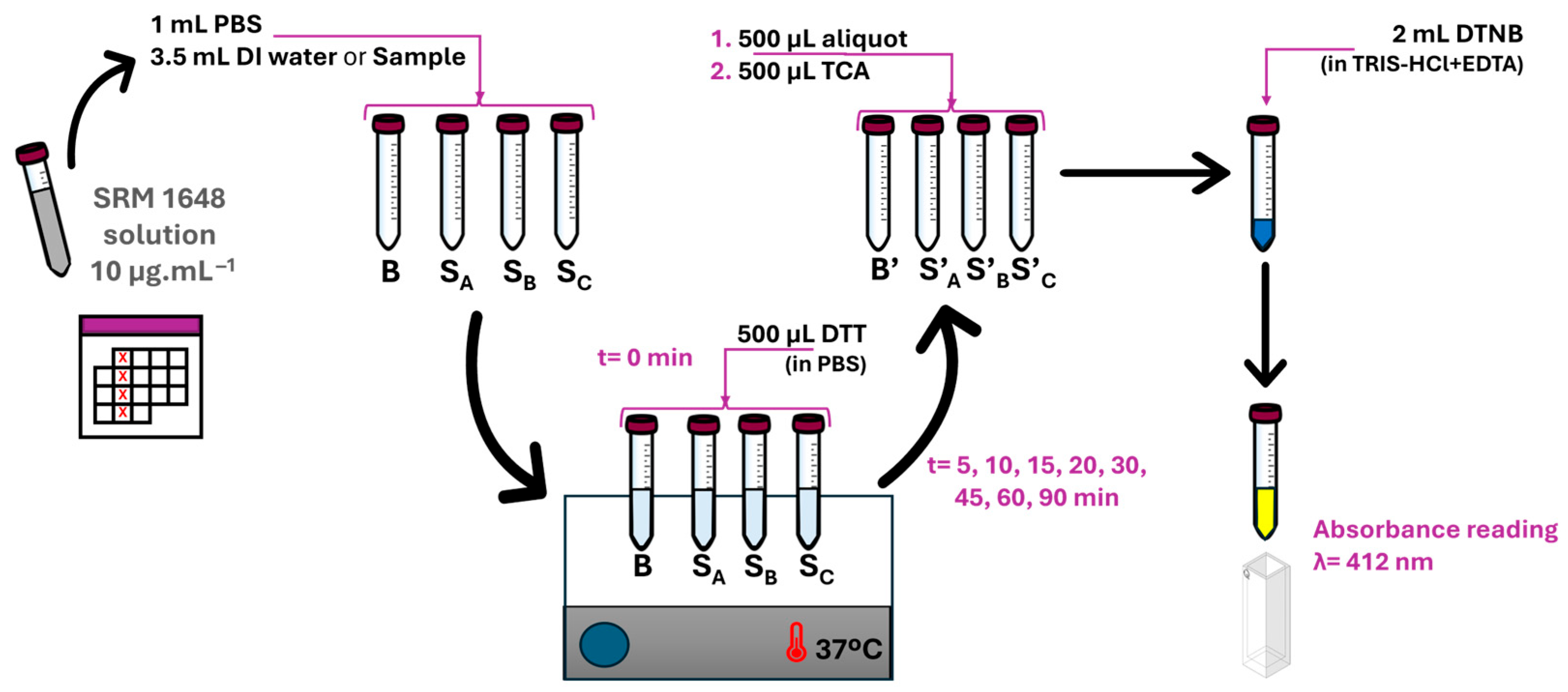

2.1. Oxidative Potential DTT Assay

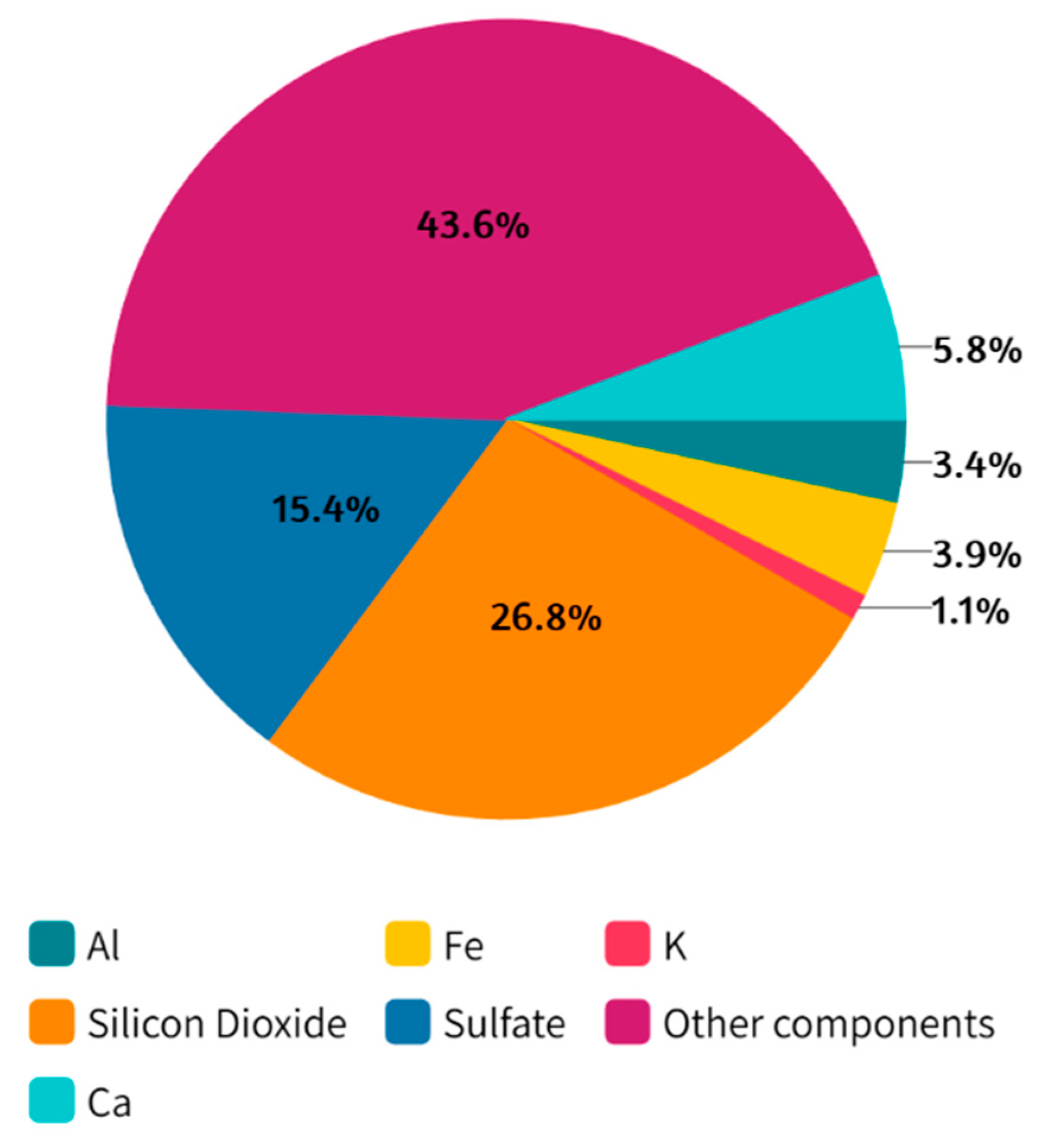

2.2. Standard Reference Material Solution

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Method Validation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of the Order of Addition of the TCA Solution

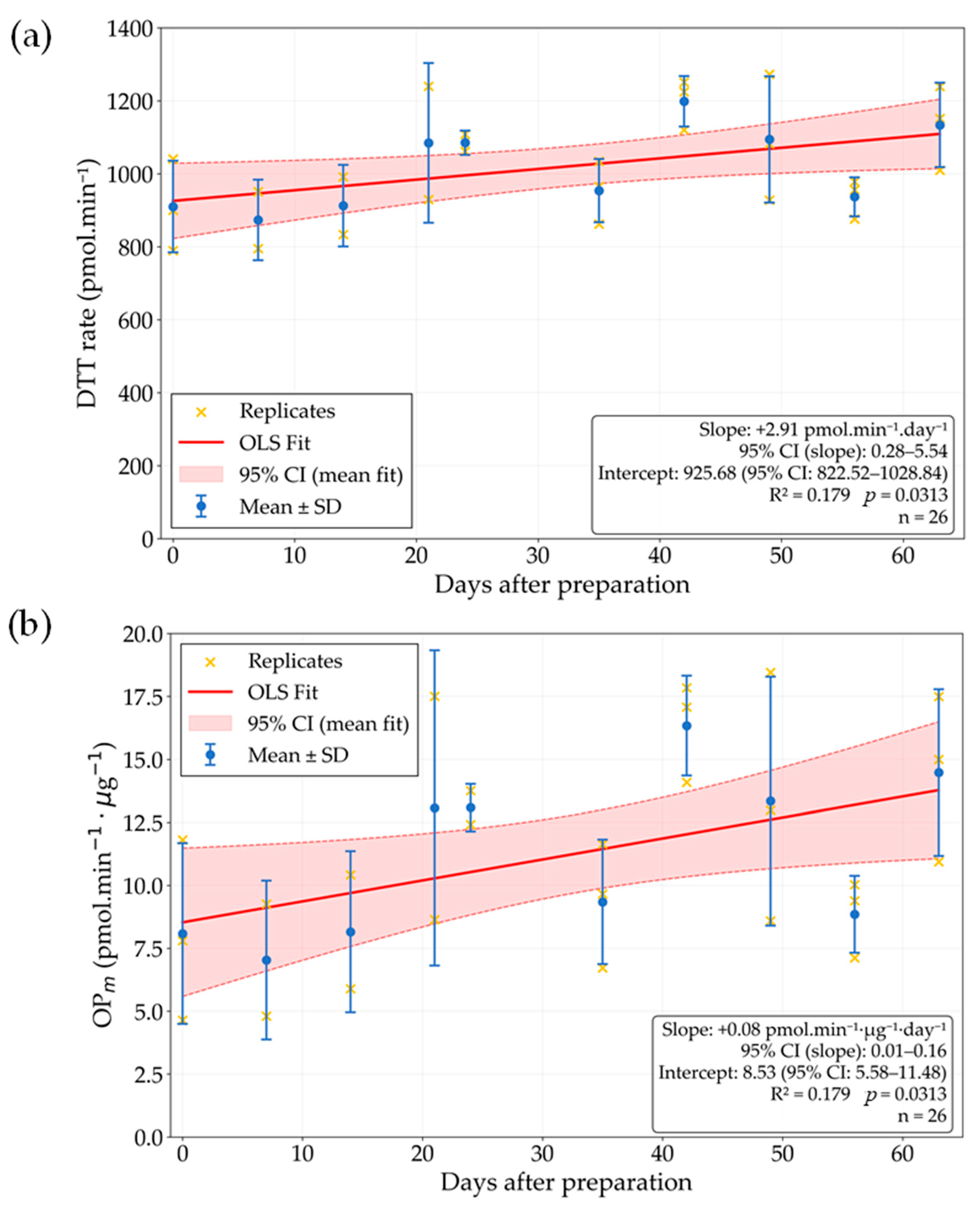

3.2. SRM Solution Stability

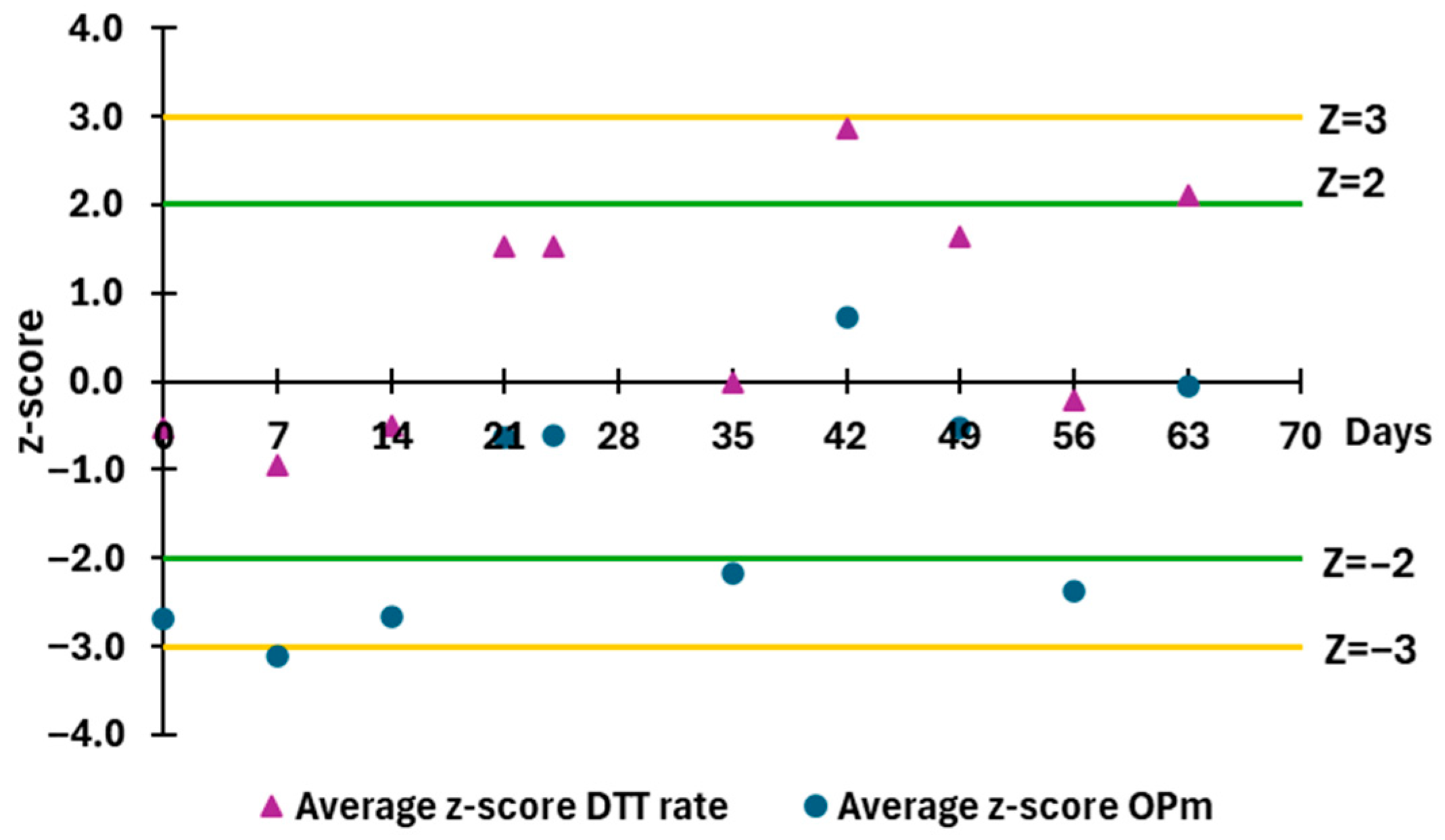

3.3. Quality Control Metrics

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almetwally, A.A.; Bin-Jumah, M.; Allam, A.A. Ambient Air Pollution and Its Influence on Human Health and Welfare: An Overview. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 24815–24830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Sioutas, C.; Weber, R.J. Oxidative Properties of Ambient Particulate Matter—An Assessment of the Relative Contributions from Various Aerosol Components and Their Emission Sources. ACS Symp. Ser. 2018, 1299, 389–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanti Das, T.; Wati, M.R.; Fatima-Shad, K. Oxidative Stress Gated by Fenton and Haber Weiss Reactions and Its Association with Alzheimer’s Disease. Arch. Neurosci. 2014, 2, e60038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Xia, T.; Nel, A.E. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Ambient Particulate Matter-Induced Lung Diseases and Its Implications in the Toxicity of Engineered Nanoparticles. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.T.; Fang, T.; Verma, V.; Zeng, L.; Weber, R.J.; Tolbert, P.E.; Abrams, J.Y.; Sarnat, S.E.; Klein, M.; Mulholland, J.A.; et al. Review of Acellular Assays of Ambient Particulate Matter Oxidative Potential: Methods and Relationships with Composition, Sources, and Health Effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 4003–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Mulholland, J.A.; Russell, A.G.; Weber, R.J. Characterization of Water-Insoluble Oxidative Potential of PM2.5 Using the Dithiothreitol Assay. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 224, 117327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiser, J. Oxidative Stress. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2012, 36, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Verma, V.; Guo, H.; King, L.E.; Edgerton, E.S.; Weber, R.J. A Semi-Automated System for Quantifying the Oxidative Potential of Ambient Particles in Aqueous Extracts Using the Dithiothreitol (DTT) Assay: Results from the Southeastern Center for Air Pollution and Epidemiology (SCAPE). Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2015, 8, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulou, D.; Bougiatioti, A.; Stavroulas, I.; Fang, T.; Lianou, M.; Liakakou, E.; Gerasopoulos, E.; Weber, R.; Nenes, A.; Mihalopoulos, N. Yearlong Variability of Oxidative Potential of Particulate Matter in an Urban Mediterranean Environment. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 206, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. European Parliament Directive (EU) 2024/2881 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2024 on Ambient Air Quality and Cleaner Air for Europe (Recast). Off. J. Eur. Union 2024, 1–70. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/2881/oj (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Gao, D.; Ripley, S.; Weichenthal, S.; Godri Pollitt, K.J. Ambient Particulate Matter Oxidative Potential: Chemical Determinants, Associated Health Effects, and Strategies for Risk Management. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 151, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominutti, P.A.; Jaffrezo, J.-L.; Marsal, A.; Mhadhbi, T.; Elazzouzi, R.; Rak, C.; Cavalli, F.; Putaud, J.-P.; Bougiatioti, A.; Mihalopoulos, N.; et al. An Interlaboratory Comparison to Quantify Oxidative Potential Measurement in Aerosol Particles: Challenges and Recommendations for Harmonisation. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2025, 18, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, A.K.; Sioutas, C.; Miguel, A.H.; Kumagai, Y.; Schmitz, D.A.; Singh, M.; Eiguren-Fernandez, A.; Froines, J.R. Redox Activity of Airborne Particulate Matter at Different Sites in the Los Angeles Basin. Environ. Res. 2005, 99, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrier, J.G.; Anastasio, C. On Dithiothreitol (DTT) as a Measure of Oxidative Potential for Ambient Particles: Evidence for the Importance of Soluble Transition Metals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 9321–9333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirizzi, D.; Cesari, D.; Guascito, M.R.; Dinoi, A.; Giotta, L.; Donateo, A.; Contini, D. Influence of Saharan Dust Outbreaks and Carbon Content on Oxidative Potential of Water-Soluble Fractions of PM2.5 and PM10. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 163, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation. ICH Q2(R2) Validation of Analytical Procedures—Scientific Guideline; International Council for Harmonisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-q2r2-guideline-validation-analytical-procedures-step-5-revision-1_en.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- National Institute of Standards & Technology. Standard Reference Material 1648. 1998. Available online: https://tsapps.nist.gov/srmext/certificates/archives/1648.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- National Institute of Standards & Technology. Certificate of Analysis Standard Reference Material 1648a Urban Particulate Matter; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. Available online: https://tsapps.nist.gov/srmext/certificates/1648a.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Mitkus, R.J.; Powell, J.L.; Zeisler, R.; Squibb, K.S. Comparative Physicochemical and Biological Characterization of NIST Interim Reference Material PM2.5 and SRM 1648 in Human A549 and Mouse RAW264.7 Cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2013, 27, 2289–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, B.R.; Smith, K.R.; Veranth, J.M.; Aust, A.E. Bioavailability of Iron from Coal fly Ash: Mechanisms of Mobilization and of Biological Effects. Inhal. Toxicol. 2000, 12, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.R.; Aust, A.E. Mobilization of Iron from Urban Particulates Leads to Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species in Vitro and Induction of Ferritin Synthesis in Human Lung Epithelial Cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997, 10, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, E. Limit of Detection and Limit of Quantification Determination in Gas Chromatography. In Advances in Gas Chromatography; Guo, X., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.N.; Miller, J.C. Statistics and Chemometrics for Analytical Chemistry; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz, S.; Falkmer, T.; Passmore, A.E.; Parsons, R.; Andreou, P. The Case for Using the Repeatability Coefficient When Calculating Test–Retest Reliability. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahpoury, P.; Zhang, Z.W.; Filippi, A.; Hildmann, S.; Lelieveld, S.; Mashtakov, B.; Patel, B.R.; Traub, A.; Umbrio, D.; Wietzoreck, M.; et al. Inter-Comparison of Oxidative Potential Metrics for Airborne Particles Identifies Differences between Acellular Chemical Assays. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2022, 13, 101596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farner, J.M.; De Tommaso, J.; Mantel, H.; Cheong, R.S.; Tufenkji, N. Effect of Freeze/Thaw on Aggregation and Transport of Nano-TiO2 in Saturated Porous Media. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 1781–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Xia, J.; Chen, M. Research on the Effect of Freeze–Thaw Cycles at Different Temperatures on the Pore Structure of Water-Saturated Coal Samples. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 27649–27655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, C.; Andrade, C.; Manzano, C.A.; Richard Toro, A.; Verma, V.; Leiva-Guzmán, M.A. Dithiothreitol-Based Oxidative Potential for Airborne Particulate Matter: An Estimation of the Associated Uncertainty. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 29672–29680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | TCA Before | TCA After | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average OPm (pmol.min−1.µg−1) | 14.6 | 14.4 | 14.8 |

| Standard deviation (pmol.min−1.µg−1) | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.4 |

| Coefficient of variation | 16.2% | 18.0% | 15.9% |

| Number of replicas | 20 | 10 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vicente, C.; Gonçalves, S.; Gamelas, C.; Almeida, S.M.; Canha, N. An Approach to Quality Control of the Dithiothreitol (DTT) Assay for the Determination of Oxidative Potential of Atmospheric Particulate Matter. Environments 2026, 13, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010006

Vicente C, Gonçalves S, Gamelas C, Almeida SM, Canha N. An Approach to Quality Control of the Dithiothreitol (DTT) Assay for the Determination of Oxidative Potential of Atmospheric Particulate Matter. Environments. 2026; 13(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleVicente, Carolina, Sara Gonçalves, Carla Gamelas, Susana Marta Almeida, and Nuno Canha. 2026. "An Approach to Quality Control of the Dithiothreitol (DTT) Assay for the Determination of Oxidative Potential of Atmospheric Particulate Matter" Environments 13, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010006

APA StyleVicente, C., Gonçalves, S., Gamelas, C., Almeida, S. M., & Canha, N. (2026). An Approach to Quality Control of the Dithiothreitol (DTT) Assay for the Determination of Oxidative Potential of Atmospheric Particulate Matter. Environments, 13(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010006