2.1. LCA Methodology and Scenarios

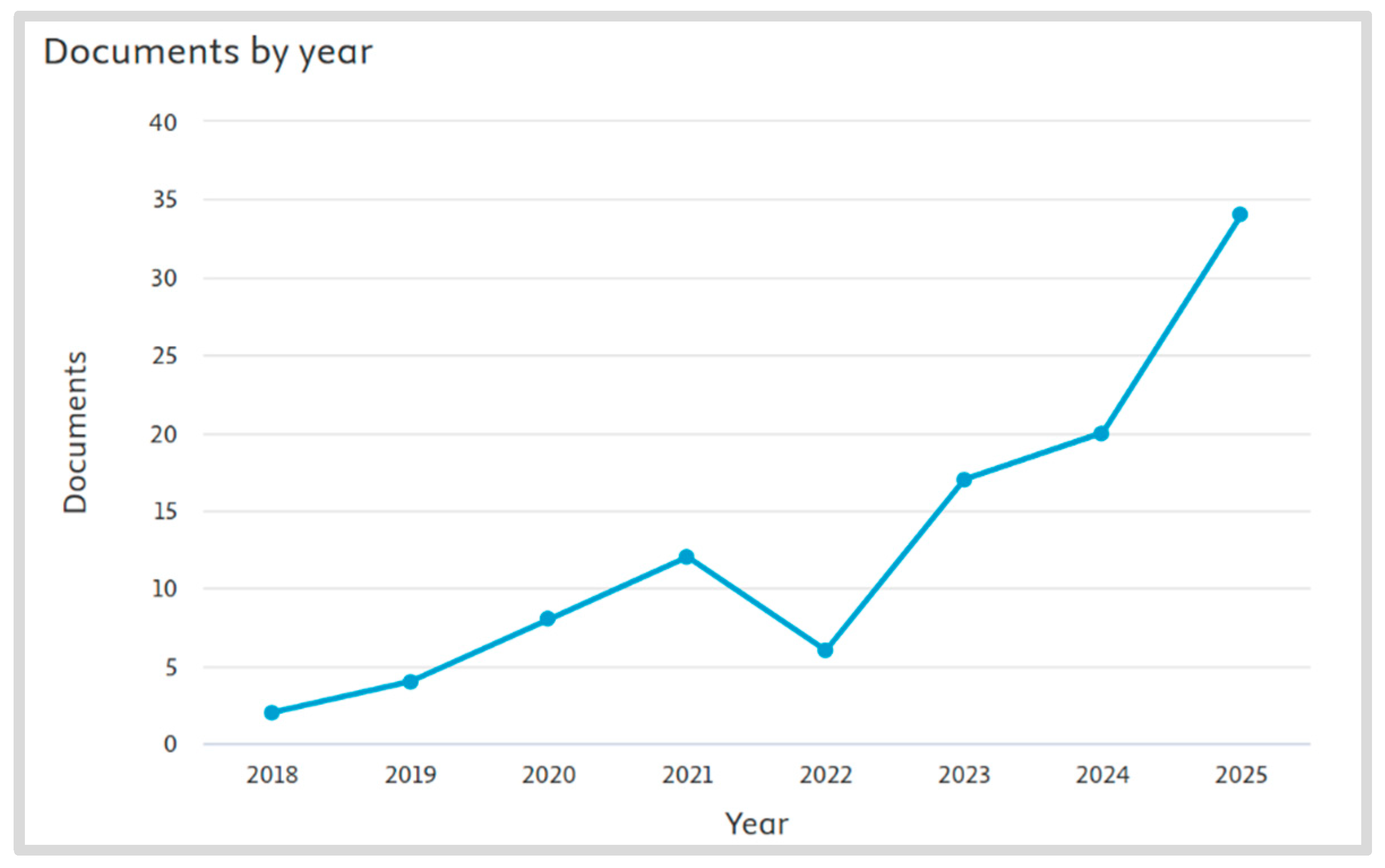

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is the methodology employed in this study to evaluate the environmental impacts of aquafaba production [

18]. LCA is a standardized analytical framework that quantifies the potential environmental effects of a product or process throughout its entire life cycle, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal. The methodology consists of four main phases: goal and scope definition, life cycle inventory (LCI), life cycle impact assessment (LCIA), and interpretation. The LCI involves the compilation and quantification of inputs (energy, raw materials) and outputs (emissions, waste) for all processes within the system boundaries. The LCIA translates these inventory data into potential environmental impacts using characterization factors for different impact categories, such as climate change. The functional unit (FU) serves as the reference basis for all calculations and comparisons, ensuring that environmental impacts are normalized to a consistent quantitative measure.

2.1.1. Objective and Scope

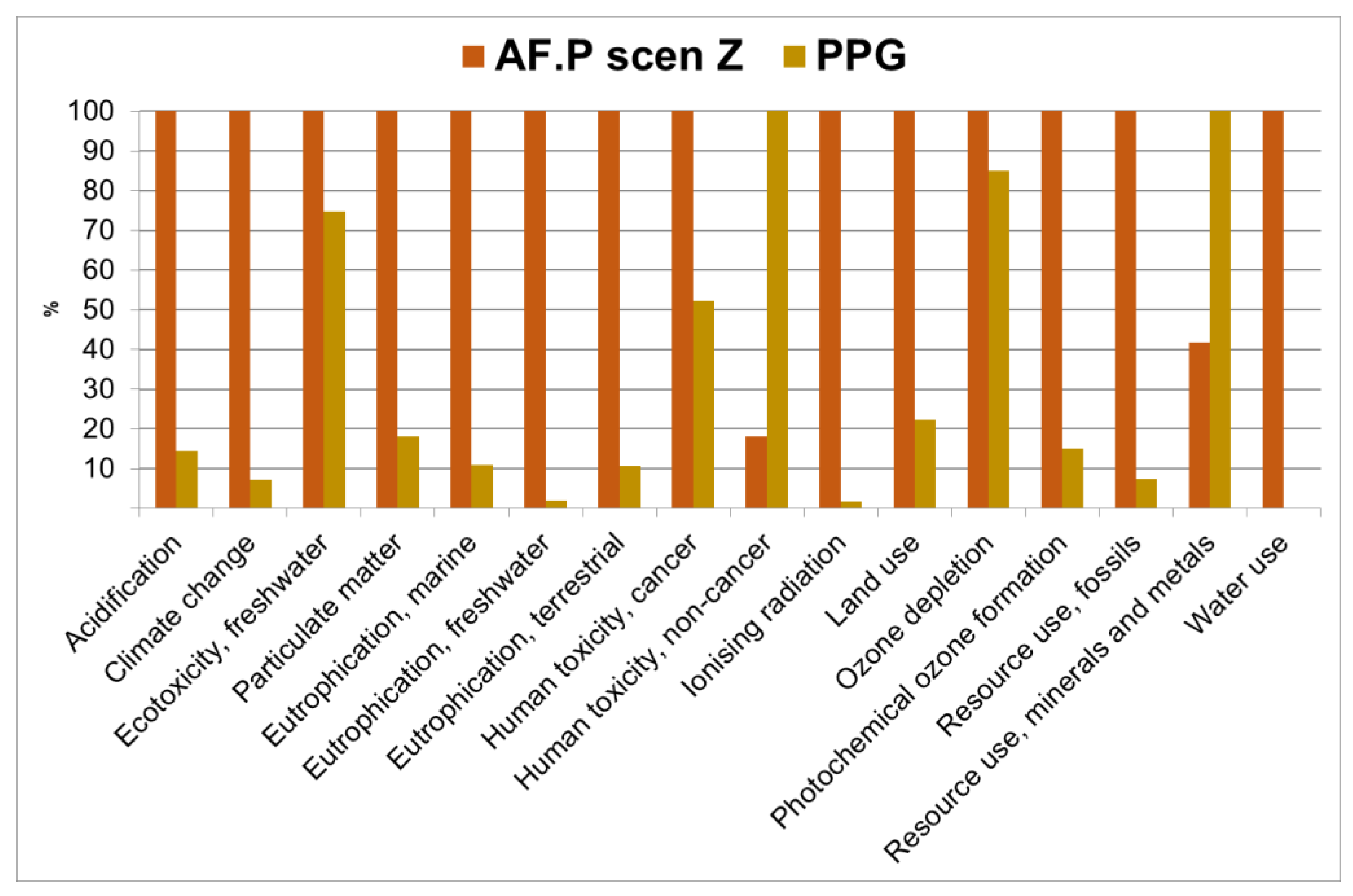

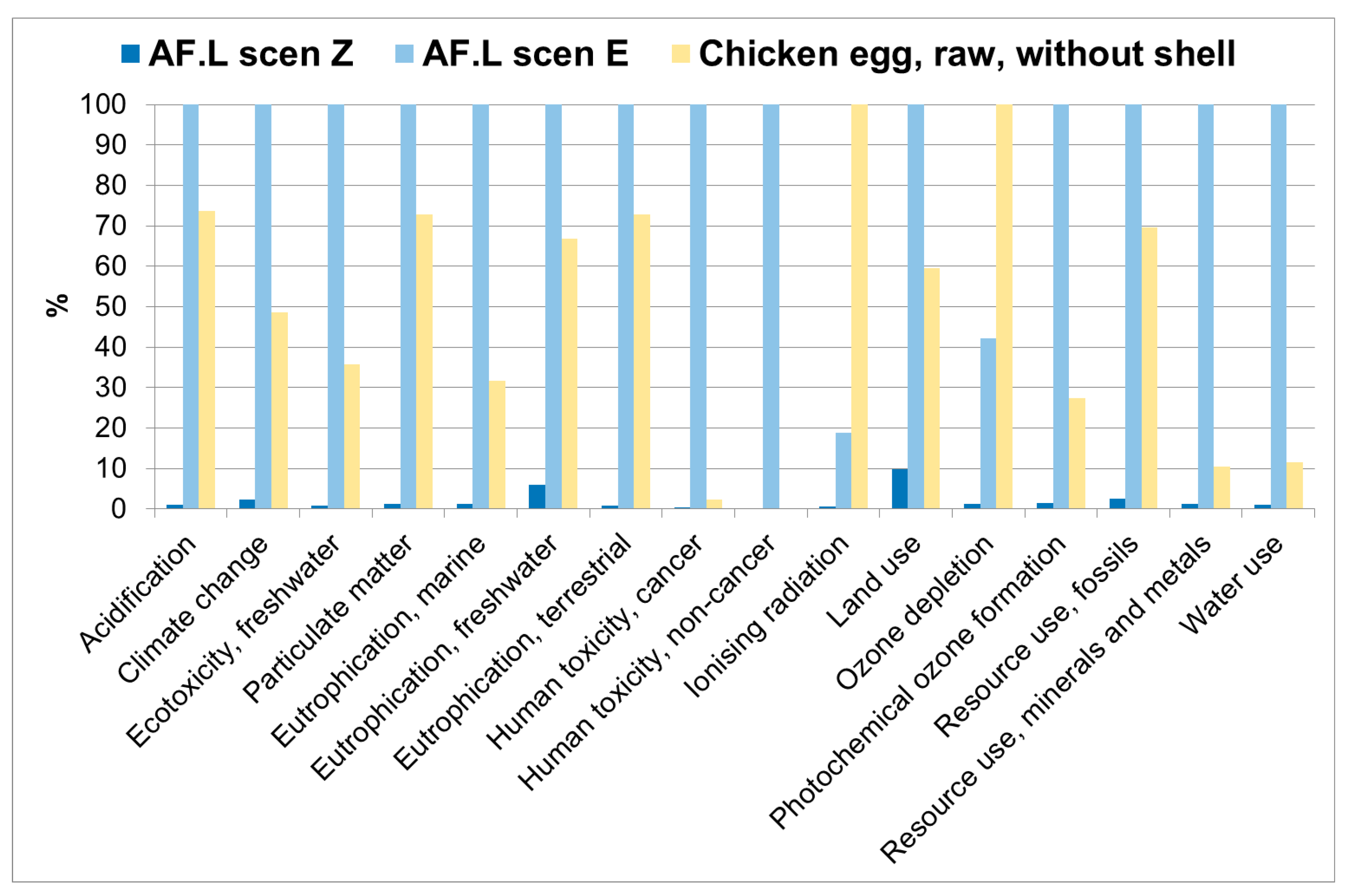

To the best of our knowledge, no LCA study has been applied to the aquafaba sector. This study represents the first comprehensive LCA of aquafaba production, serving as a preliminary environmental assessment to establish a baseline for future standardized analyses. The objective is to evaluate the potential environmental impacts associated with producing aquafaba in two distinct forms for different sectoral applications: powdered aquafaba (AFp) for cosmetic and industrial uses, and liquid aquafaba with stabilizing additives (AFL) for food applications.

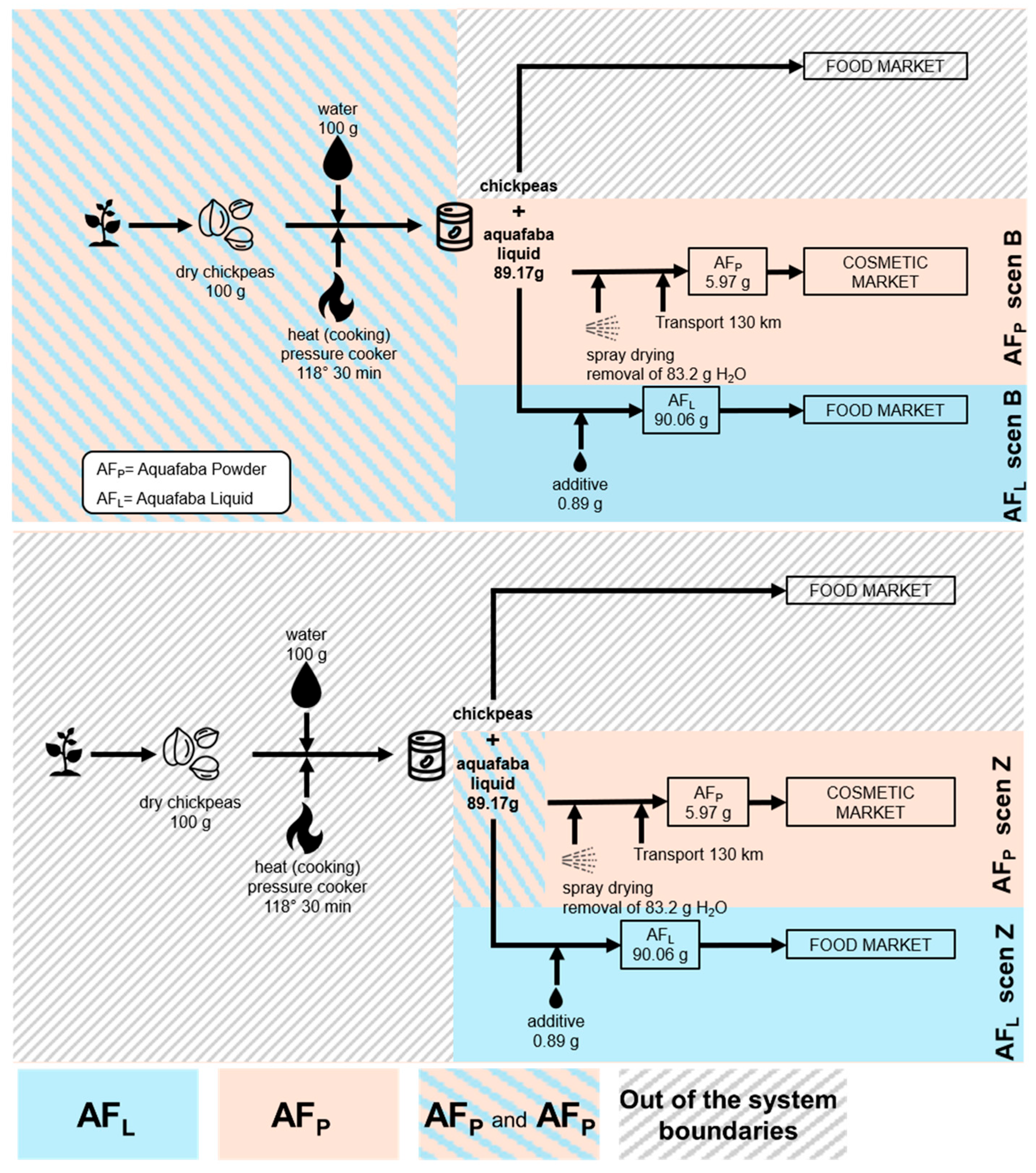

Two functional units were defined to reflect the different applications: 100 g of powdered aquafaba (AF

P) and 100 g of liquid aquafaba with 1% guar gum by weight (AF

L). The system boundaries follow a cradle-to-gate approach, encompassing all processes from chickpea cultivation to the production of ready-to-use aquafaba forms, as shown in

Figure 2. The study stopped at the gate, without including downstream stages, since no specific use scenario (i.e., specific type of cosmetic) and end-of-life stage were considered.

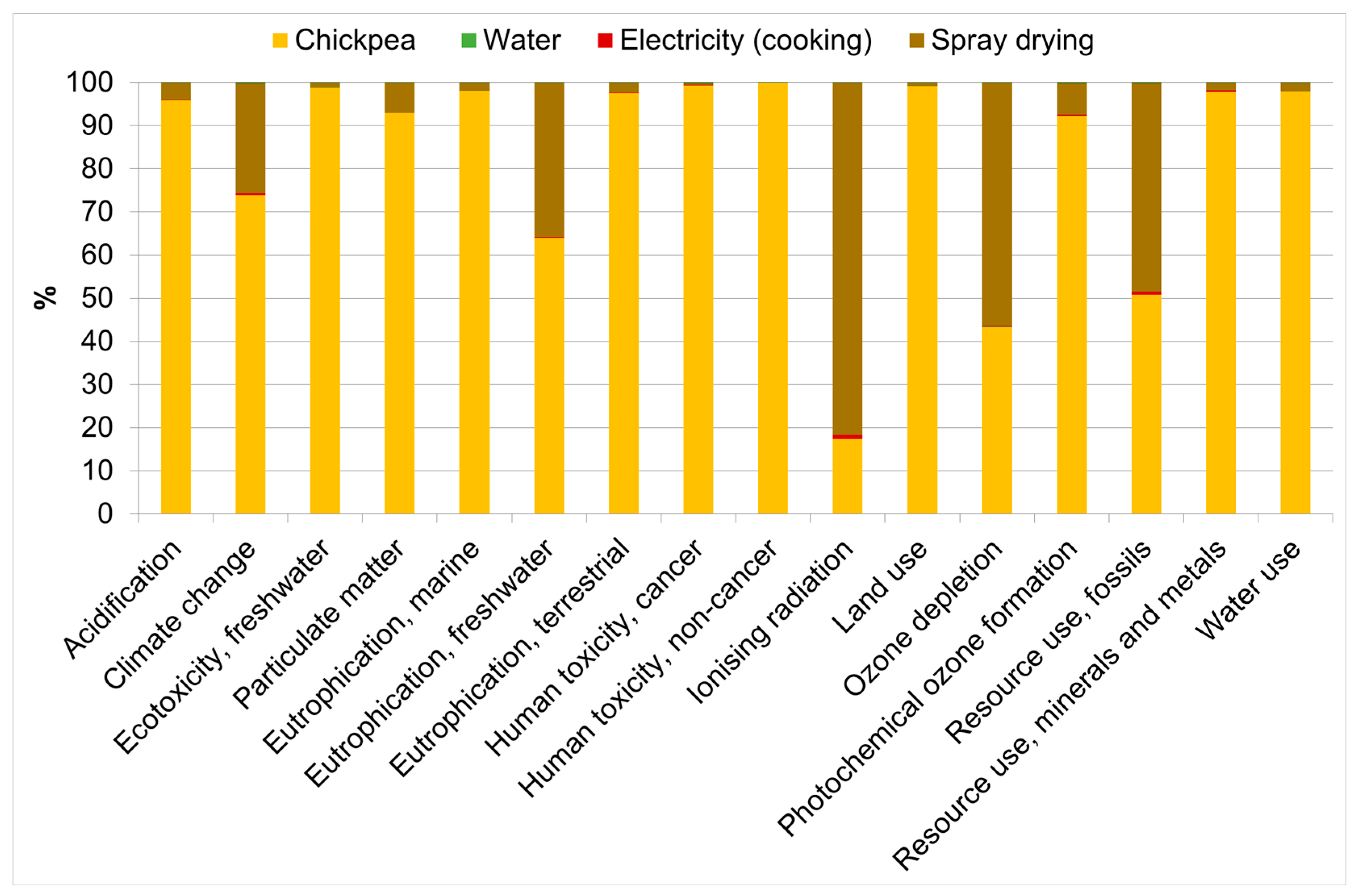

For AFP, this includes chickpea cultivation, cooking to obtain liquid aquafaba, spray drying processes, and transport. For AFL, the system included chickpea cultivation, cooking, and additive incorporation, while excluding the energy-intensive spray drying step. The environmental performance of each aquafaba form was then compared against sector-specific conventional alternatives: AFP versus PPG in cosmetic applications, and AFL versus chicken eggs in food applications. Distribution, usage, and end-of-life phases were excluded due to the wide range of potential applications and the preliminary nature of this assessment.

A functional unit of 100 g was selected for both powdered and liquid aquafaba. This quantity reflects a realistic scale for individual culinary or cosmetic applications, such as the substitution of one egg in food formulations, and allows a manageable comparison with sector-specific conventional alternatives. The selected scale also facilitates the interpretation and communication of environmental impacts at a product-relevant level.

2.1.2. Scenarios Analyzed

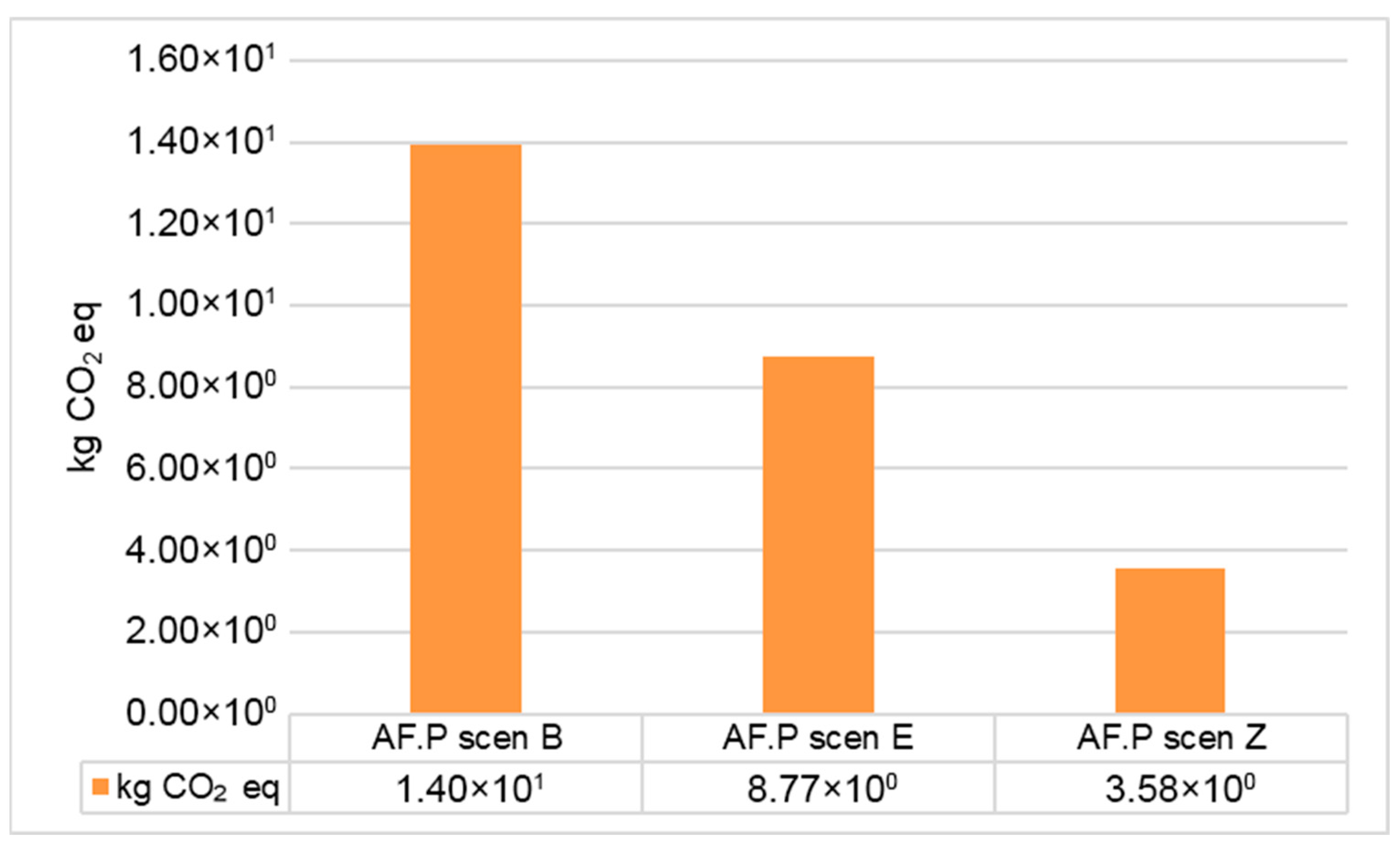

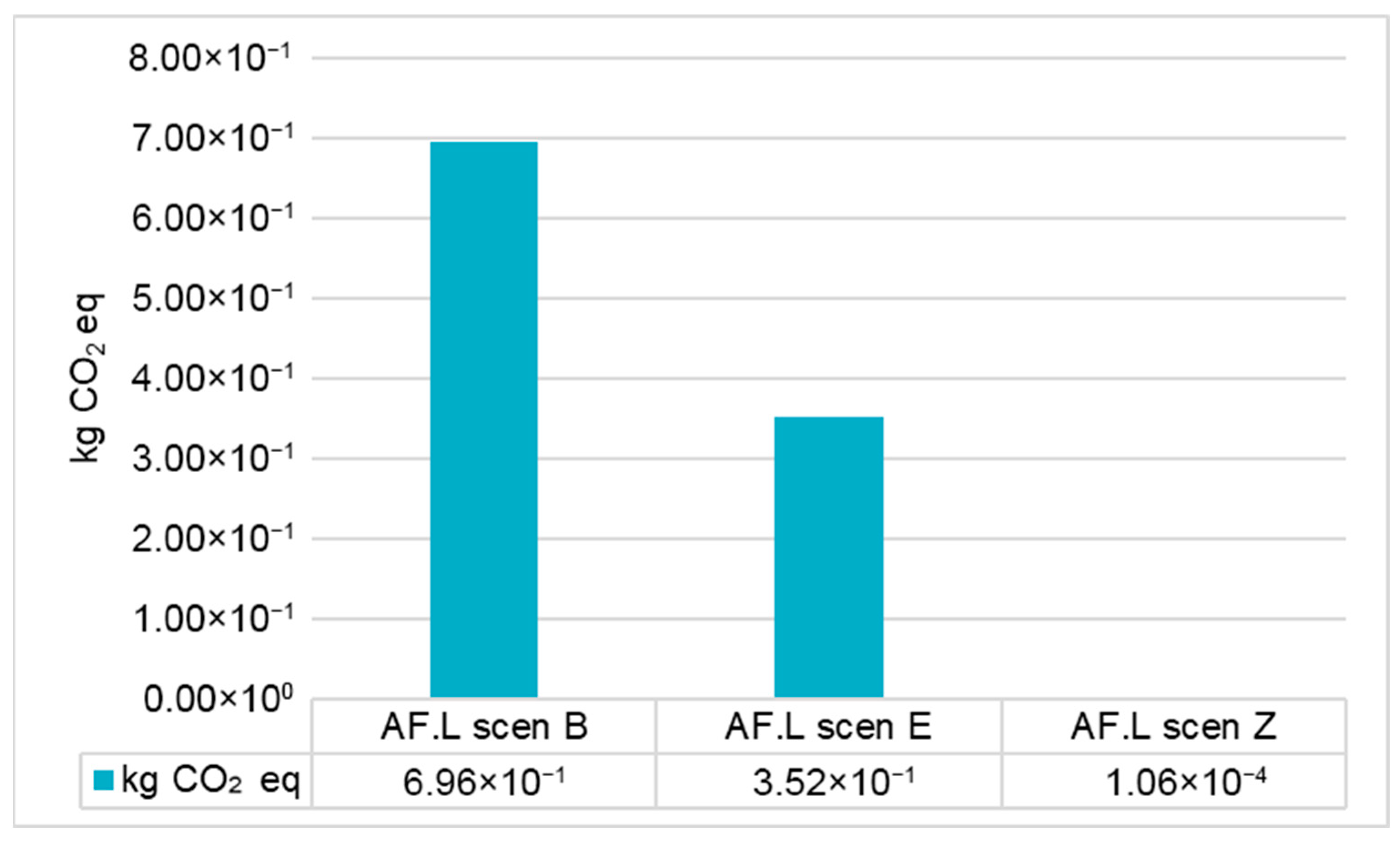

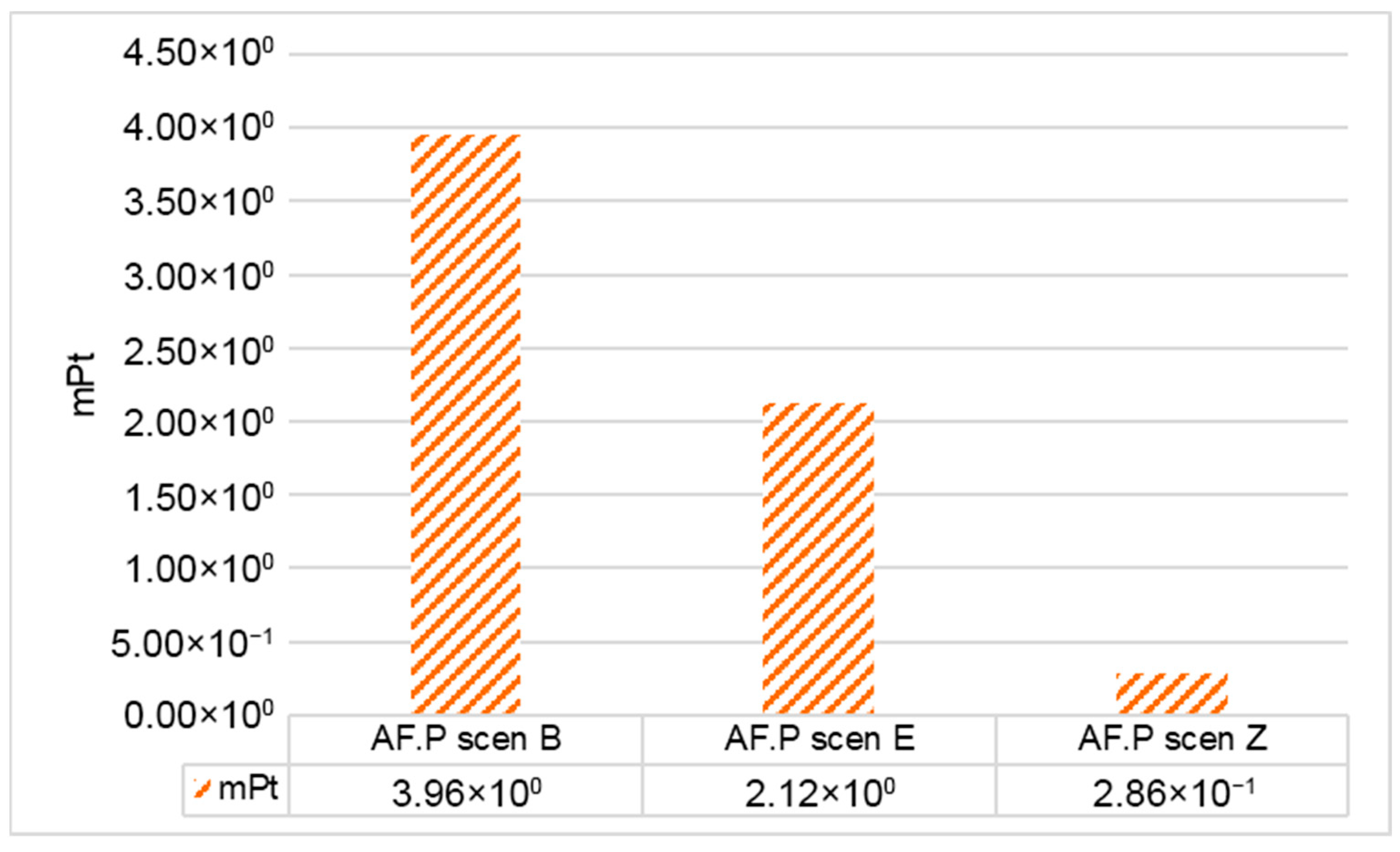

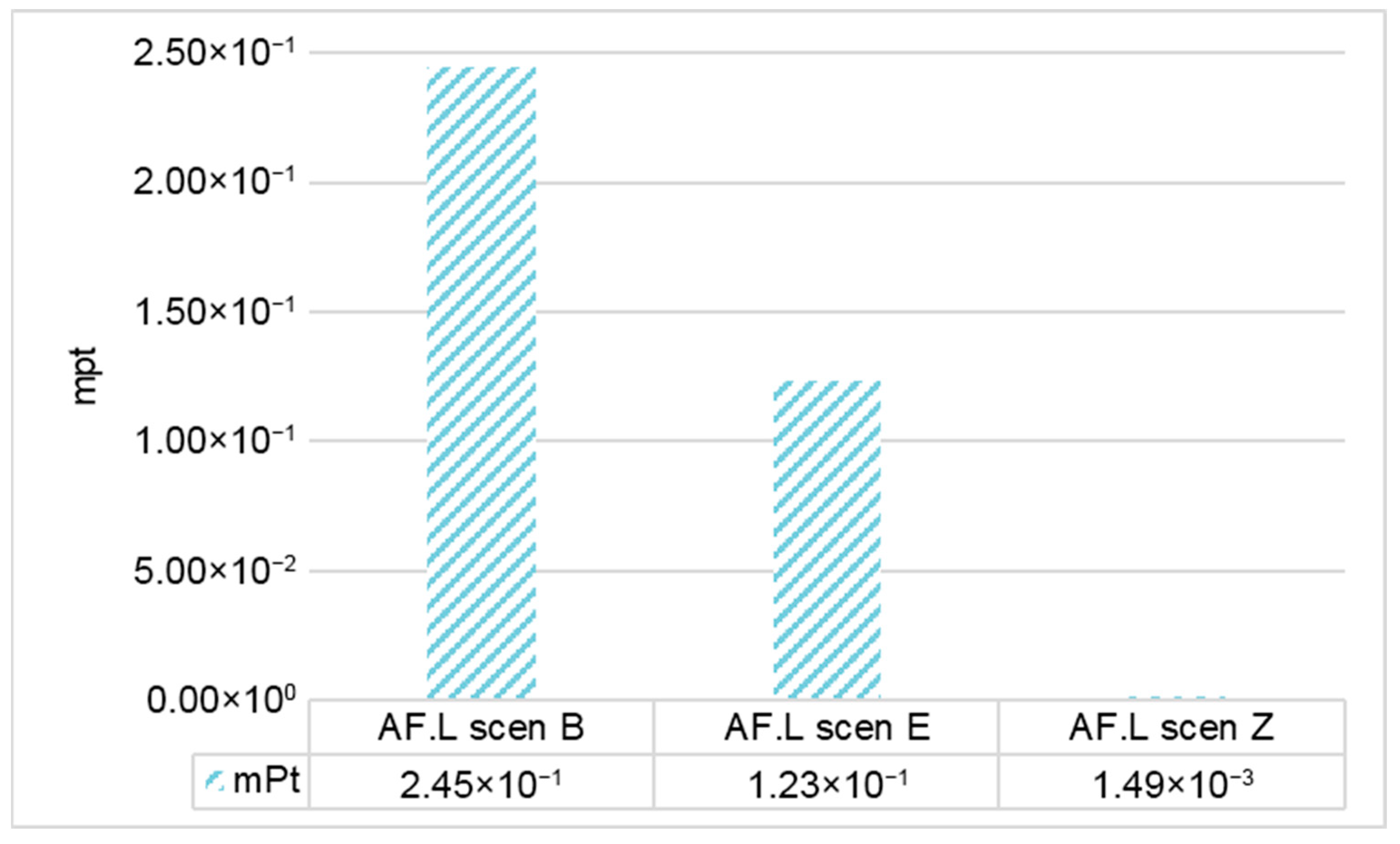

To provide a comprehensive and robust evaluation, three distinct production scenarios were considered for aquafaba, reflecting different approaches to byproduct allocation and energy sourcing. These scenarios, described below, are crucial for understanding how different production contexts and allocation methods can significantly influence the environmental footprint of powdered aquafaba.

scen B—Baseline Scenario (Full Allocation): This scenario represents the most conservative approach to environmental impact assessment. In this scenario, powdered aquafaba is treated as the primary product of interest and therefore bears the full environmental burden associated with the entire production chain. This includes all impacts from chickpea cultivation, the cooking process to extract liquid aquafaba (i.e., energy consumption for heating, water usage), and the spray drying process to produce the powdered form (i.e., electricity consumption, equipment operation). This scenario assumes that the cooked chickpeas, which are co-produced during the aquafaba extraction process, have no economic value or alternative use, making aquafaba responsible for 100% of the environmental impacts. While this approach may overestimate the environmental burden of the aquafaba, it provides a conservative upper bound for impact assessment and is useful for worst-case scenario planning.

scen Z—Zero Burden Scenario (Waste Valorization): This scenario represents the most optimistic approach and reflects the original concept of aquafaba as a waste valorization opportunity. In this scenario, liquid aquafaba is considered a byproduct or waste stream from existing chickpea processing operations (such as canned chickpea production, industrial chickpea cooking for food manufacturing, or restaurant/food service operations). Since this liquid would otherwise be discarded as waste, requiring disposal costs and potentially causing environmental problems, it is assigned zero environmental burden from the upstream processes (chickpea cultivation and cooking) [

19]. The environmental impact assessment focuses exclusively on the downstream processing required to convert the “free” liquid aquafaba into powdered form, primarily the spray drying operation. This scenario represents the ideal case for circular economy principles, where waste streams are converted into valuable products without additional resource extraction (within the same facility or not). It demonstrates the maximum environmental benefit that can be achieved when aquafaba is truly utilized as a waste valorization strategy.

scen E—Economic Allocation Scenario: This scenario adopts a more realistic approach by recognizing that aquafaba production typically occurs alongside the production of other valuable co-products, particularly cooked chickpeas or chickpea flour. In this allocation method, the environmental impacts from chickpea cultivation and cooking are distributed between aquafaba and its co-products in proportion to their respective economic values in the market. For example, if liquid aquafaba accounts for 15% of the total economic value generated from the combined products (aquafaba + cooked chickpeas), then it would be allocated 15% of the shared environmental burden from the upstream processes. This approach reflects the economic reality of integrated production systems where multiple products contribute to the overall revenue stream. The economic allocation method is particularly relevant for industrial-scale production, where both aquafaba and chickpea are marketed as separate commodities. This scenario typically results in a significant reduction in environmental impacts attributed to aquafaba compared to the baseline scenario. It is important to note that this allocation is based on an analysis of the Italian market conducted in May 2025. As market prices for these commodities are subject to fluctuation, this economic allocation should not be viewed as a definitive measure but rather as a relevant snapshot. The values provide a useful baseline but require periodic updates to accurately reflect changing market conditions.

In addition to the different allocation scenarios, both aquafaba powder (AFP) and liquid aquafaba (AFL) are considered in this study. Two distinct models were developed because these product forms are utilized in distinct sectors and involve different production steps. The aquafaba produced under these scenarios serves as the basis for comparative LCA studies against conventional alternatives:

For cosmetic applications: Powdered aquafaba is compared against PPG, a widely used synthetic emulsifier. The environmental data for PPG is sourced from the Environmental Footprint database [

20], specifically the process “

Polypropylene glycol {GLO}|Technology mix|Production mix, at plant|LCI result”.

For food applications: Liquid aquafaba with stabilizing additives is compared against whole eggs, considering their emulsifying and binding properties. To follow a conservative approach, the comparison includes guar gum addition (1% by weight) to the liquid aquafaba, although some applications have demonstrated successful egg substitution using liquid aquafaba without any additives.

2.2. Life Cycle Inventories

To perform the LCA in SimaPro 10.2, processes from ecoinvent (version 3.10) [

21], AGRIBALYSE

® (version 3.2) [

22], and the Environmental Footprint (EF) database [

20] are used.

In the case of the ecoinvent database, the Cut-off system model was selected. This system model selection was based on methodological consistency with the AGRIBALYSE

® database [

22], which provides the agricultural background data for chickpea production. The Cut-off approach treats recyclable materials and waste streams by “cutting off” their environmental burdens at the beginning of treatment processes, making them available burden-free for secondary applications [

21]. This approach is particularly well-suited for the zero-burden scenario employed in this study, where aquafaba is conceptualized as a waste valorization opportunity from existing chickpea processing operations.

Due to the unavailability of primary data from the industrial supplier, the LCI for aquafaba powder production was compiled using secondary data from scientific literature. The energy inputs utilize the Italian energy mix from the International Energy Agency (IEA) [

23].

The production scenario (

Table 1) is based on the experimental work of He et al. [

16], with results consistent with their subsequent study [

24]. The process starts with 100 g of dry chickpeas and 100 g of distilled water, cooked in a pressure cooker at 115–118 °C for 30 min. The average yield of liquid aquafaba was 89.17 g, ranging from 70.90 g to 107.44 g per 100 g of chickpeas. Assuming an average moisture content of 93% (ranging from 92% to 94%), drying this liquid yields 5.97 g of powder [

16].

The aquafaba composition and processing parameters used in this study are validated by independent research from Mustafa et al. [

4] who characterized commercial canned chickpea aquafaba. Their analysis revealed a composition of 94% water, 1.5% protein, 0.5% ash, and approximately 4% carbohydrates, with no detectable fat content. This composition corresponds to a moisture content of 94%, which is remarkably consistent with the 93% average moisture content used in our calculations based on He et al. [

16].

An important consideration for the LCI is the distinction between dry and fresh chickpea mass. According to the ecoinvent database properties for chickpeas, fresh chickpeas contain 21.1% dry mass and 78.9% moisture. This means that the 100 g of “dry chickpeas” specified in the He et al. [

16] methodology actually corresponds to approximately 473 g of fresh chickpeas. This correction was applied for having accurate environmental impact allocation, as the ecoinvent process “

chickpea {GLO}|market for chickpea“ refers to fresh chickpeas as traded commercially.

The energy consumption for cooking was estimated based on a professional electric cooker (SIGMA EC60 6.45 kW maximum power, 45 L capacity) [

25]. The calculation considers the temperature difference between ambient conditions (25 °C) and cooking temperature (118 °C) compared to the maximum achievable temperature (190 °C). The energy consumption was then linearly scaled from the full 48 L capacity to the experimental volume of 0.2 L.

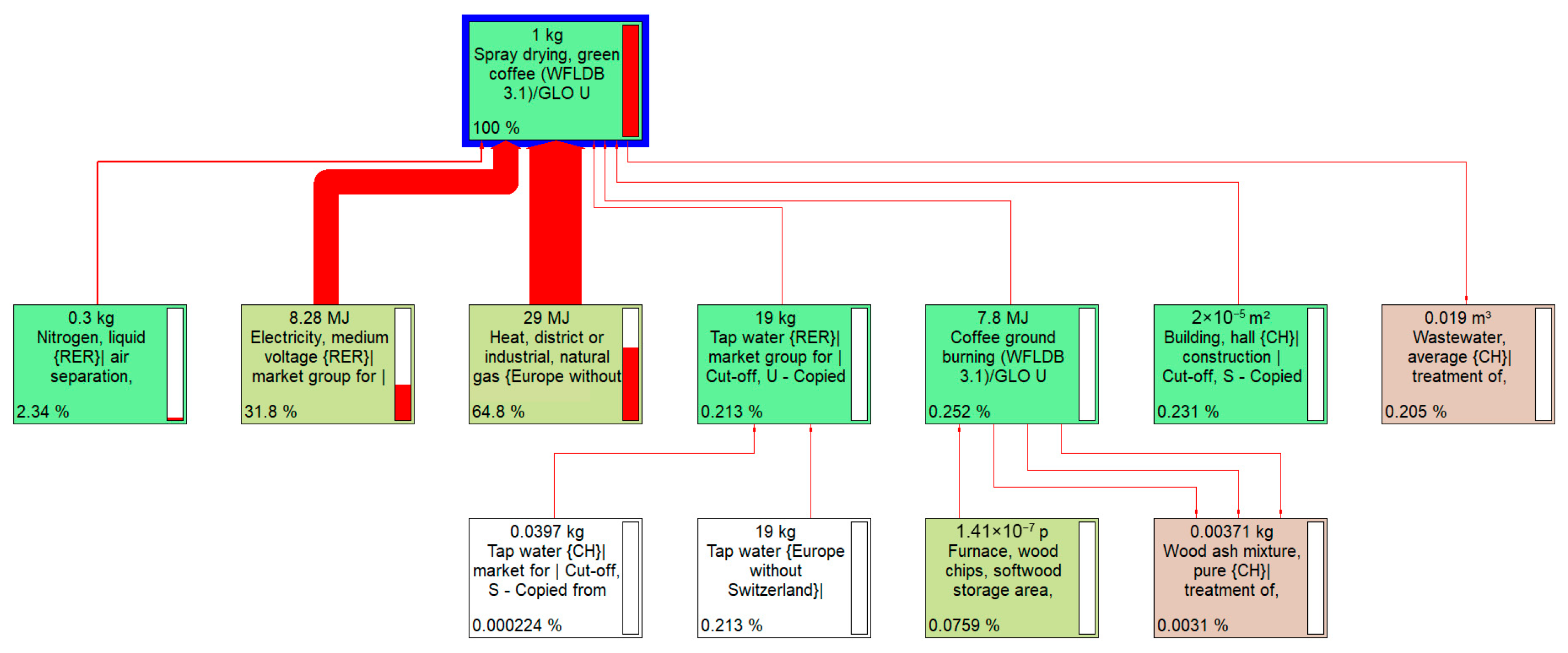

The environmental impacts associated with spray drying were determined using a process-based approach rather than generic energy calculations. This methodology employs the AGIBALYSE [

24] process “

Spray drying, green coffee (WFLDB 3.1) {GLO}|U” as a reference system, which provides a comprehensive representation of industrial spray drying operations, including energy consumption, equipment utilization, and auxiliary material requirements. The scaling methodology is based on the fundamental principle that spray drying energy requirements are primarily determined by the quantity of water that must be evaporated from the feed material. In fact, the primary energy consumption in the spray drying process includes the steam required for air heating and the electricity consumed by intake and exhaust fans during the drying operation [

26]. This can also be noted from network representation of impact on climate change of the process (

Figure 3), where it is shown that 64.5% of the impact is linked to the heat.

Figure 3 shows the network analysis generated through the SimaPro software for the spray-drying process only, highlighting the relative contribution of energy and auxiliary inputs to the climate change impact category.

The reference coffee process transforms 2.22 kg of wet coffee into 1.00 kg of dried product, requiring the removal of 1.22 kg of water. In the aquafaba production scenario, 89.17 g of liquid aquafaba (representing the average yield from 100 g of dry chickpeas as determined by He et al. [

16]) is processed to yield 5.97 g of powder (AFP), necessitating the evaporation of 83.2 g of water. The process scaling factor is calculated as the ratio of water removal requirements between the aquafaba and coffee systems. This approach yields a scaling factor of 0.0682 (calculated as 0.0832 ÷ 1.22 kg).

Transportation impacts are selectively included based on the anticipated application scenarios for each aquafaba form. For powdered aquafaba (AF

P), transportation is included in the system boundaries, as this product is primarily intended for cosmetic and industrial applications requiring transport to specialized manufacturing facilities located at different sites. For liquid aquafaba (AF

L), transportation is excluded from the assessment, assuming utilization within the food sector at the same production facility where chickpeas are processed. The transport calculation assumes a default distance of 130 km and considers a lorry EURO4, as recommended by PEF document [

20], for transporting 89.17 g of liquid aquafaba, resulting in 11.58 kgkm.

For the zero-burden scenario, which considers aquafaba as a waste valorization opportunity, the inventory includes only the downstream processing impacts.

The inventories presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3 have been modelled for aquafaba powder production, which is primarily utilized as a substitute in the cosmetic sector.

In the food sector, aquafaba can also be used directly in liquid form (AF

L), eliminating the need for spray drying. Mustafa et al. [

4] indicates that liquid aquafaba has been successfully employed in some applications without any additives, while other studies have demonstrated the need for stabilizing agents to achieve optimal functional performance [

1]. To conduct a conservative analysis that accounts for potential additive requirements, guar gum has been included in the liquid aquafaba inventory (

Table 4). Based on typical formulations reported by Xu et al. [

1], a concentration of 1% guar gum by weight of liquid aquafaba represents a conservative estimate for applications requiring enhanced emulsion stability, such as mayonnaise production. The additive was selected among various natural gums, such as xanthan gum, tragacanth gum, and Arabic gum, because guar gum is available in the AGRIBALYSE

® database.

This is the inventory for the complete AFL process; for the zero-burden AFL scenario, as with AFP scen Z, the cooking phase is not considered.

An economic allocation approach was implemented to address the multi-functional nature of the aquafaba production process. This allocation method distributes environmental impacts proportionally to the economic value of co-products, in accordance with LCA methodology standards [

18]. The rationale for economic allocation stems from the production process characteristics, where chickpea processing yields both aquafaba powder and chickpea flour as valuable outputs.

Currently, chickpea flour represents the primary market product for most producers, while aquafaba remains a niche product. However, as the focus of this study is on aquafaba, the chickpea flour production process was excluded from the system boundaries. The economic allocation recognizes that the market value of products justifies the existence of the production facility.

A comprehensive market survey was conducted to determine the economic allocation factor and it’s shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6. The analysis included multiple commercial brands for both products, and it is referred to May 2025.

Based on these market values, environmental impacts from chickpea cultivation and cooking are allocated proportionally between the two products. The significantly higher market value of aquafaba powder (approximately 18 times that of chickpea flour) reflects its specialized applications and limited commercial availability. The observed price ranges (€3.00–11.99/kg for chickpea flour and €60.75–176.30/kg for aquafaba powder) demonstrate significant market variability.

From 1 kg of dry chickpeas, the process yields approximately 1 kg of chickpea flour and 59.7 g of aquafaba powder. Despite the significant difference in mass output, the revenue analysis reveals a more balanced economic contribution: chickpea flour generates 7.23 € per kg of dry chickpeas, while aquafaba powder contributes 7.86 € (59.7 g × 131.68 €/kg).

The economic allocation factor for aquafaba powder is therefore:

This result indicates that aquafaba, representing only 6% of the total mass output, accounts for approximately 52% of the economic value generated from dry chickpea processing. This allocation factor is applied to all upstream inputs (chickpeas, water, and cooking energy), while the spray drying process remains fully allocated to aquafaba as it provides no benefit to the flour co-product.

In the economic allocation scenario, the impacts related to chickpeas and their cooking are distributed between the two co-products according to the calculated allocation percentage (52.1%), while the impacts of spray drying (for AFP) or additive production (for AFL) are considered in their entirety and allocated exclusively to aquafaba.