Induced Phytoextraction of Heavy Metals from Soils Using Brassica juncea and EDTA: An Efficient Approach to the Remedy of Zinc, Copper and Lead

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Composition of the Soil Used in the Experiment

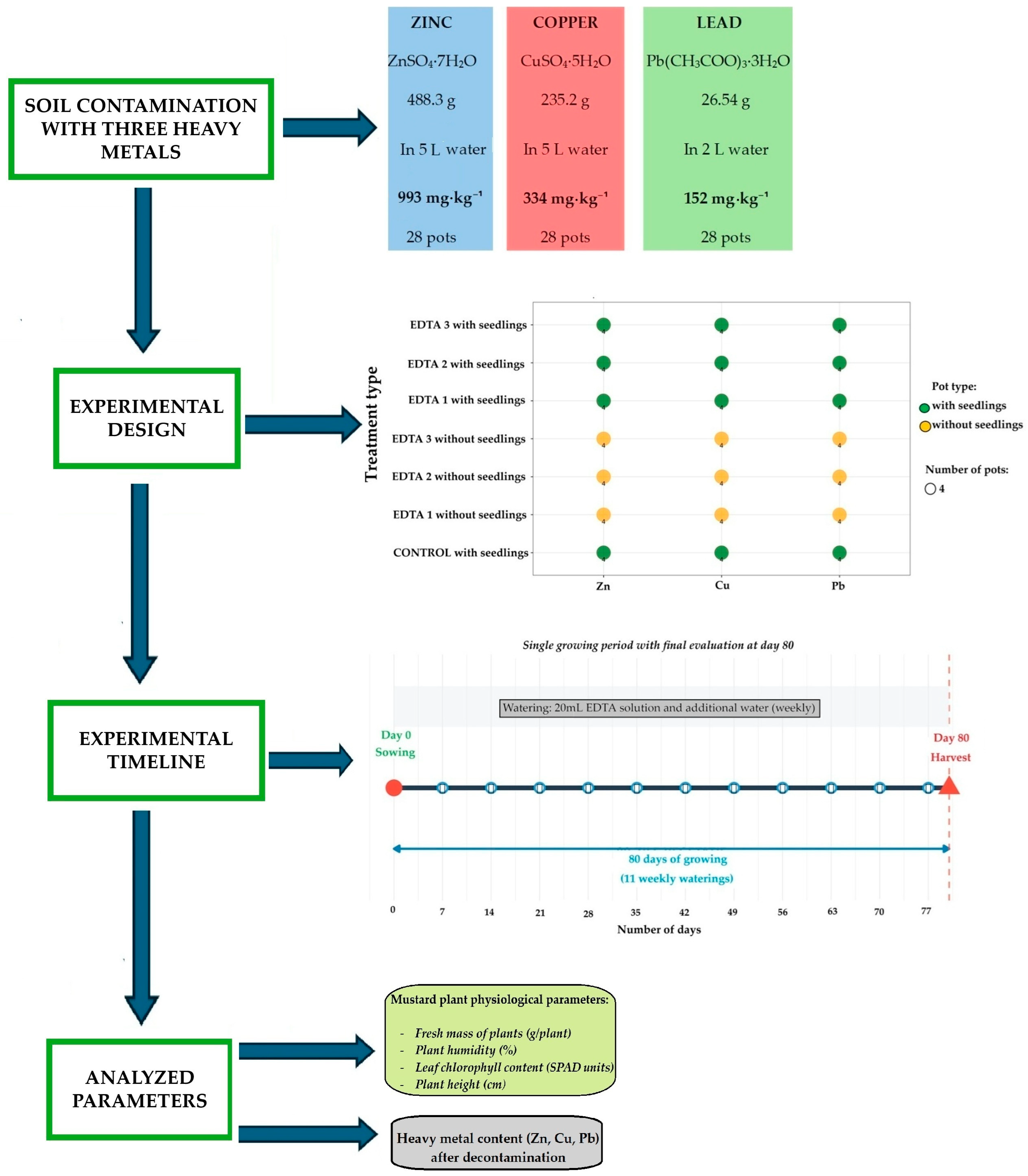

2.2. Soil Contamination Procedure

- Preparation of solutions: the salts corresponding to each metal were dissolved in the indicated volumes of water, obtaining concentrated, completely transparent aqueous solutions.

- Solution application: the entire amount of soil (112 kg) was placed in a suitable container, and the concentrated solution was added gradually, with continuous mixing, to allow uniform distribution of the metals.

- Homogenization: the soil was mixed manually and mechanically, using an electric concrete mixer (Imer Syntesi 140 type, IMER Group, Poggibonsi, Italy), until complete homogenization and uniform distribution of metals in the total soil mass were achieved.

- Stabilization: the contaminated soil was left to rest for 24 h, to allow the penetration and uniformity of metals before distribution into pots (4 kg/pot).

2.3. Applied Decontamination Methods

- The biological method, which consisted of sowing Indian mustard seeds (Brassica juncea) in the contaminated soil, without applying EDTA. 10 seeds were sown in each pot at a depth of approximately 1 cm. After emergence (5–7 days), 3 uniform plants/pot were selected, which were maintained throughout the experiment (80 days).

- The chemical method, which consisted of adding EDTA solution (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, disodium salt Na2EDTA·2H2O) in three concentrations equivalent to 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mmol·kg−1 dry soil, to the pots with soil contaminated with each metal (Zn, Cu, Pb);

- Mixed method (chemical-biological), which combined Indian mustard sowing in contaminated soil, according to the biological method, followed by weekly watering with EDTA solution, in the same concentrations (0.5–1.0–2.0 mmol·kg−1 dry soil).

2.4. Design Experimental

- Biological method: 12 pots containing soil contaminated (4 kg/pot) with each metal (Zn, Cu, Pb), in which Indian mustard seeds were sown and watered only with water.

- Chemical method: 36 pots with contaminated soil, treated weekly with three different EDTA solutions (EDTA1, EDTA2, EDTA3), obtained from stock solutions of 15,625, 31,250 and 62,500 mmol·L−1. Each stock solution was diluted 1:4 (v/v) with water before application, and the treatments corresponded to final doses of 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mmol·kg−1 dry soil.

- Mixed method: 36 pots in which Indian mustard seeds were sown and treated weekly with the same three diluted EDTA solutions (EDTA1–EDTA3), corresponding to the same three dosage levels.

2.5. Experimental Determinations

- Fresh weight of plants, determined by weighing immediately after harvest;

- Chlorophyll content, determined with a SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan), the results being expressed in SPAD units;

- Water content (plant moisture), calculated gravimetrically based on the difference between fresh and dry weight, according to standard methodology;

- Plant height, measured with a millimeter ruler.

2.6. Statistical Processing

3. Results

3.1. Statistical Results and Mathematical Modeling Regarding Soil Metal Content

- Zinc (Zn) values recorded the most pronounced decrease, from 993 mg·kg−1 to 481.8 mg·kg−1 in the Indian mustard and EDTA 2.0 mmol·kg−1 treatment, representing a 51.5% reduction. This significant decrease (p < 0.001) demonstrates a superior mobilization of zinc under the chelating action of EDTA, potentiated by the rhizospheric activity of Indian mustard, which confirms the combined remediation efficiency.

- Copper (Cu) content values progressively decrease from 534 mg·kg−1 in the control soil to 387.2 mg·kg−1 in the Indian mustard and EDTA 2.0 mmol·kg−1 variant. This 27.5% reduction indicates a high efficiency of the combined treatment, highlighting a synergistic interaction between the phytoremediation achieved by Indian mustard and EDTA chelation. The differences between the treatments are highly statistically significant (p < 0.001), confirming the substantial effect of the concentration and combination on copper mobilization.

- Lead (Pb) concentration decreased significantly from 152 mg·kg−1 in the control soil to 96.8 mg·kg−1 also in the Indian mustard and EDTA 2.0 mmol·kg−1 variant, corresponding to a reduction of 36.3%. Treatments with EDTA applied alone had a moderate efficiency, but the combination with Indian mustard intensified the phytoextraction and chelation processes. The results (p < 0.001) confirm that mixed treatments represent the most efficient strategy for reducing lead accumulation in contaminated soil.

- The integrated analysis highlights a clear trend of reducing Cu, Pb and Zn concentrations as the EDTA concentration increases, with maximum efficiency in combinations with Indian mustard. The results confirm the synergy between the biological phytoextraction processes and the chemical chelation processes, with Indian mustard and EDTA 0.5–1.0–2.0 mmol·kg−1 treatments achieving the highest percentage reductions (p < 0.001). These variants can be considered optime strategies for remediation of soils contaminated with these heavy metals.

- One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc Tukey HSD test were applied to evaluate the effect of the treatments: Indian mustard, EDTA (0.5–1.0–2.0 mmol·kg−1) and mixed Indian mustard and EDTA (0.5–1.0–2.0 mmol·kg−1) on the content of heavy metals (Cu, Zn, Pb) in contaminated soil.

- The results of the one-way ANOVA analysis revealed highly significant differences (p < 0.001) between treatments for all analyzed metals with F-statistic values of 2274.08 for Zn, 995.64 for Cu, 147.00 for Pb. These results demonstrate the efficiency of the combined Indian mustard and EDTA treatments, especially at concentrations of 1.0 and 2.0 mmol·kg−1, which determined the most pronounced reductions in Zn, Cu, Pb concentrations compared to the control. Overall, the ANOVA analysis confirms that both the type of treatment and the EDTA concentration exert a significant and differentiated effect on the soil remediation processes.

3.2. Statistical Analysis of the Effect of Treatments on the Physiological Parameters of Indian Mustard (Brassica juncea) in Soil Contaminated with Cu, Zn and Pb

- Fresh weight of Indian mustard plants, Figure 2A, responded significantly to EDTA application in heavy metal contaminated soils. ANOVA analysis revealed significant treatment effects for copper (F = 6.315, p = 0.0081), zinc (F = 7.155, p = 0.0052) and lead (F = 14.419, p = 0.0003). Tukey post hoc test showed that only the highest concentration of EDTA 3 caused a significant decrease in fresh weight compared to Indian mustard without EDTA (p < 0.05). The most drastic decrease was recorded for lead, where the weight decreased from 17.305 ± 5.965 g/plant in Indian mustard without EDTA to 2.532 ± 1.056 g/plant in EDTA 2. This suggests a phytotoxic effect of EDTA at high concentrations, probably through excessive mobilization of metals in the soil solution and their increased uptake by the plant [41,42,43,44].

- The chlorophyll content, represented by the SPAD index, Figure 2B, did not show significant differences between treatments for any of the tested metals (Cu: p = 0.2013; Zn: p = 0.0686; Pb: p = 0.7537). The values ranged between 5.862 ± 0.286 SPAD (Zn, EDTA 3) and 10.425 ± 2.716 SPAD (Zn, Indian mustard only, no EDTA). The lack of a significant response suggests that chlorophyll biosynthesis was not critically affected by EDTA treatments under the experimental conditions, even in the presence of metal-induced stress [27,45,46,47,48].

- The relative humidity of plant tissues, Figure 2C, was significantly influenced by EDTA only in the case of lead (F = 21.705, p < 0.0001), where the EDTA 3 treatment reduced the water content from 73.612 ± 3.727% to 53.09 ± 2.324%. For copper (p = 0.0996) and zinc (p = 0.1152), the variations were not statistically significant. The decrease in humidity in lead under the EDTA 3 treatment may be associated with osmotic stress and damage to cell membranes under the influence of the increased toxicity of the mobilized metal [45,49].

- Plant height, Figure 2D, demonstrated the strongest response to EDTA application, with extremely strong significant effects for all metals (Cu: F = 98.532, p < 0.0001; Zn: F = 53.966, p < 0.0001; Pb: F = 160.526, p < 0.0001). Tukey’s test revealed a significant growth stimulation at EDTA 1 compared to the Indian mustard treatment alone, without EDTA, for all metals, with maximum values of 21.475 ± 0.881 cm for copper and 18.25 ± 0.37 cm for lead. In contrast, EDTA 3 strongly inhibited growth [50,51], reducing the height to 13.4 ± 0.392 cm (Cu), 15.675 ± 0.457 cm (Zn) and 12.75 ± 0.265 cm (Pb). This biphasic response (stimulation at low concentration, inhibition at high concentration) is characteristic of the hormesia effect [52] and indicates an optimization of growth at low doses of EDTA, probably by alleviating ionic stress.

- Zinc (Zn) showed a dual effect, specific to essential elements. At low or moderate concentrations of EDTA, Zn supported physiological processes, contributing to maintaining an optimal level of tissue moisture, increasing chlorophyll content and slightly superior vegetative development compared to the control. However, at high doses of EDTA, Zn began to exhibit inhibitory effects, reflected by a reduction in fresh weight and a moderate decrease in plant height, suggesting exceeding the optimal physiological threshold and the establishment of metal stress.

- Copper (Cu), although an essential element in small quantities, caused a series of more pronounced negative effects at the concentrations used by EDTA compared to Zn. A significant decrease in chlorophyll content was observed, associated with inhibition of photosynthesis. Tissue moisture and fresh weight were negatively affected, reflecting disruption of cellular metabolism and possible changes in water absorption. Plant height progressively decreased with increasing EDTA concentration at Cu, indicating a strong impact on vegetative growth.

- Lead (Pb), an element with high toxic potential, generated the most pronounced inhibitions for all physiological parameters studied. Pb visibly reduced chlorophyll content, indicating damage to the photosynthetic system, and drastically decreased fresh weight, reflecting severe disturbances in water metabolism and biomass development. Humidity levels were also reduced, suggesting altered root absorption. Plant height was severely limited, especially at high EDTA concentrations, confirming the general inhibitory effect of lead on vegetative growth.

- Biphasic response to EDTA: hormesis and phytotoxicity. The observed biphasic effect of EDTA on plant height, significant stimulation at 0.5 mmol·kg−1 followed by inhibition at 2.0 mmol·kg−1, aligns with the concept of hormesis in plant-metal interactions [52]. Low concentrations of EDTA may ameliorate metal toxicity by forming soluble complexes that reduce the activity of free metal ions, while high concentrations likely enhance metal uptake beyond plant tolerance thresholds. This pattern has been documented in Brassica juncea for Pb-EDTA complexes [50,51], where optimal chelation improved metal translocation without compromising biomass.

- Metal-specific phytotoxicity and EDTA efficiency. The differential responses among heavy metals reflect distinct chemical behaviors and phytotoxic mechanisms. The pronounced reduction in fresh weight and moisture content for Pb at 2.0 mmol·kg−1 EDTA (Figure 2A,C) suggests efficient formation of Pb-EDTA complexes and subsequent uptake by plants [50,51,52,53].

- Physiological tolerance mechanisms in Indian mustard. The maintenance of chlorophyll content in all treatments (Figure 2B) suggests that the photosynthetic apparatus of Brassica juncea possesses considerable resilience to stress induced by metal-EDTA complexes. This could be attributed to: (1) compartmentalization of metals in vacuoles via HMA transporters [53], (2) upregulation of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and CAT observed in EDTA-treated Indian mustard [26], or (3) structural stability of chloroplastic membranes under the action of moderate chelation [16,20,22,28].

- Moisture content as an indicator of physiological stress. The significant reduction in lead-specific moisture content at high EDTA concentration (Figure 2C) may indicate a disruption of water relations due to: (1) metal-induced stomatal closure, reducing transpiration [45], (2) affecting the hydraulic conductivity of roots through damage to aquaporins by metals [49], or (3) osmotic stress caused by the accumulation of metal-chelate complexes. The fact that this effect was metal-specific (absent for copper and zinc) suggests different modes of action on water transport systems [21,44].

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of One-Way and Two-Way ANOVA Analyses

4.2. Evolution of Zinc (Zn) Content in Applied Treatments

4.3. Evolution of Copper (Cu) Content in the Applied Treatments

4.4. Evolution of Lead (Pb) Content in Applied Treatments

4.5. Integrated Analysis of Metal Behavior and Treatment Efficiency

4.6. Analysis of Logarithmic Functions Between the Intensity of Soil Decontamination Treatments

4.7. Analysis of Physiological Parameters of Indian Mustard Plants Grown in Soil Contaminated with Zinc, Copper and Lead

4.8. The Study’s Innovative Contributions to the Field of Remediation Research

- Definition of the “optimal concentration window”: the study clearly identifies 0.5 mmol·kg−1 EDTA as the optimal concentration for assisted phytoextraction, balancing extractive efficiency with plant health.

- Demonstrated metal specificity: the study highlights that responses to EDTA are metal-specific, requiring differentiated protocols (Pb requires special attention due to its strong effect on humidity).

- Confirmation of the photosynthetic resistance of Brassica juncea: the study shows that under conditions of extreme metal stress, the photosynthetic apparatus remains functional, supporting the potential for long-term applications.

- Quantified biphasic response: the study shows the exact quantification of the hormetic effect providing a basis for dose optimization in practical applications.

4.9. Research Limitations

- Controlled conditions: the experiment was conducted under laboratory/pot conditions, which may differ from complex field conditions (soil microbiome, climatic variations, interactions with other elements).

- Short exposure period: the long-term effects of repeated EDTA treatments have not been evaluated.

- Limited mechanistic aspects: the study evaluates physiological parameters, but does not investigate in depth the molecular or biochemical mechanisms underlying them.

- Variety specificity: The results may be specific to the Brassica juncea variety studied, requiring validation on other genotypes.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wuana, R.A.; Okieimen, F.E. Heavy Metals in Contaminated Soils: A Review of Sources, Chemistry, Risks and Best Available Strategies for Remediation. ISRN Ecol. 2011, 20, 402647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.; Wang, Y.; Tan, S.N.; Mohd Yusof, M.L.; Ghosh, S.; Chen, Z. Phytoremediation: A Promising Approach for Revegetation of Heavy Metal-Polluted Land. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, Z.; Lu, X.; Duan, Q.; Huang, L.; Bi, J. A review of soil heavy metal pollution from industrial and agricultural regions in China: Pollution and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Ilahi, I. Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology of Hazardous Heavy Metals: Environmental Persistence, Toxicity, and Bioaccumulation. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 6730305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Dai, M.; Yang, J.; Sun, L.; Tan, X.; Peng, C.; Ali, I.; Naz, I. A critical review on the phytoremediation of heavy metals from environment: Performance and challenges. Chemosphere 2021, 291, 132979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, H. Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils: Sources, Influencing Factors, and Remediation Strategies. Toxics 2024, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicińska, A.; Pomykała, R.; Izquierdo, M. Changes in soil pH and mobility of heavy metals in contaminated soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 73, e13203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ullah, S.; Umar, H.; Saghir, A.; Nasir, S.; Aslam, Z.M.; Jabbar, H.; ul Aabdeen, Z.; Zain, R. Effects of Heavy Metals on Soil Properties and their Biological Remediation. Ind. J. Pure App. Biosci. 2022, 10, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintorini, M.M.; Widyatmoko, H.; Sinaga, E.; Aliyah, N. Effect of pH on metal mobility in the soil. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 737, 012071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihali, C.; Oprea, G.; Michnea, A.; Jelea, S.G.; Jelea, M.; Man, C.; Senila, M.; Grigor, L. Assessment of heavy metals content and pollution level in soil and plants in Baia Mare area, NW Romania. Carpathian J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2013, 8, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Donici, A.; Bunea, C.I.; Calugar, A.; Harsan, E.; Racz, I.; Bora, F.D. Assessment of Heavy Metals Concentration in Soil and Plants from Baia Mare Area, NW Romania. Bull. UASVM Hortic. 2018, 75, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelescu, M.; Baconi, D.; Neagoe, A.; Iordache, V.; Stan, M.; Constantinescu, P.; Ciobanu, A.-M.; Vardavas, A.I.; Vinceti, M.; Tsatsakis, A.M. Environmental metal contamination and health impact assessment in two industrial regions of Romania. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 580, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crăciun, A.I.; Ozunu, A. Comprehensive analysis and review of soil contamination and the associated risks at the Poșta-Rât Industrial Site in Turda, Cluj, Romania. J. Eng. Sci. Innov. 2024, 9, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Schutte, B.J.; Ulery, A.; Deyholos, M.K.; Sanogo, S.; Lehnhoff, E.A.; Beck, L. Heavy Metal Contamination in Agricultural Soil: Environmental Pollutants Affecting Crop Health. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.J.; Ling, Y.E.; Halim, K.A.; Sani, B.S.; Abdullahi, N.I. Heavy metal pollution and transformation in soil: A comprehensive review of natural bioremediation strategies. J. Umm. Al-Qura Univ. Appll. Sci. 2025, 11, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, A.K.; Muruganandam, M.; Ali, S.S.; Kornaros, M. Clean-Up of Heavy Metals from Contaminated Soil by Phytoremediation: A Multidisciplinary and Eco-Friendly Approach. Toxics 2023, 11, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.K.; Kumar, N.; Singh, N.P.; Santal, A.R. Phytoremediation technologies and their mechanism for removal of heavy metal from contaminated soil: An approach for a sustainable environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1076876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Rout, C.; Singh, J.; Saharan, Y.; Goyat, R.; Umar, A.; Akbar, S.; Baskoutas, S. A review on the clean-up technologies for heavy metal ions contaminated soil samples. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. A comparative study on the efficacy of conventional and green chelating agents for soil heavy metal remediation. Theor. Nat. Sci. 2024, 37, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sut-Lohmann, M.; Grimm, M.; Kästner, F.; Raab, T.; Heinrich, M.; Fischer, T. Brassica juncea as a Feasible Hyperaccumulator of Chosen Potentially Toxic Metals Under Extreme Environmental Conditions. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2023, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Liu, D.; Hou, W. Hyperaccumulation of Lead by Roots, Hypocotyls, and Shoots of Brassica juncea. Biol. Plant. 2000, 43, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, K.; Sevugaperumal, R.; Ramasubramanian, V. Phytoextraction: Using Brassica as a Hyper Accumulator. Biochem. Physiol. 2015, 4, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.R.; Bhadra, A.; Premalatha, S.J.; Malathi, H.; Madhu, A.K.; Shrivastava, R.; Patil, S.J. Phytoremediation—A promising approach for pollution management. Eur. Chem. Bull. 2023, 12, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.A.; Perveen, K.; Khan, F.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Hock, O.G.; Bhatt, S.C.; Singh, J.; Qamar, M.O. Effect of different levels of EDTA on phytoextraction of heavy metal and growth of Brassica juncea L. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1228117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelou, M.W.H.; Bauer, U.; Ebel, M.; Schaeffer, A. The influence of EDDS and EDTA on the uptake of heavy metals of Cd and Cu from soil with tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). Chemosphere 2007, 68, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortoloti, G.; Baron, D. Phytoremediation of toxic heavy metals by Brassica plants: A biochemical and physiological approach. Environ. Adv. 2022, 8, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadir, S.; Hameed, A.; Nisa, N.T.; Azooz, M.; Wani, M.R.; Hasannuzaman, M.; Kazi, A.G.; Ahmad, P. Brassicas: Responses and Tolerance to Heavy Metal Stress. In Improvement of Crops in the Era of Climatic Changes; Ahmad, P., Wani, M.R., Azooz, M.M., Tran, L.S.P., Eds.; Springer Science: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourato, M.P.; Moreira, I.N.; Leitão, I.; Pinto, F.R.; Sales, J.R.; Martins, L.L. Effect of Heavy Metals in Plants of the Genus Brassica. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 17975–17998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecka, A.; Konkolewska, A.; Hanć, A.; Ciszewska, L.; Staszak, A.M.; Jarmuszkiewicz, W.; Ratajczak, E. Activation of antioxidative and detoxificative systems in Brassica juncea L. plants against the toxicity of heavy metals. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifullah; Meers, E.; Qadir, M.; de Caritat, P.; Tack, F.M.; Du Laing, G.; Zia, M.H. EDTA-assisted Pb phytoex-traction. Chemosphere 2009, 74, 1279–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M. Nitrogen-Total. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 3: Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Page, A.L., Helmke, P.A., Loeppert, R.H., Soltanpour, P.N., Tabatabai, M.A., Johnston, C.T., Sumner, M.E., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 1085–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.W. Exchangeable Cations. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2: Chemical and Microbiological Properties, 2nd ed.; Page, A.L., Ed.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Shazia, A.; Shazi, I.; Mahmood, U.H. Effect of chelating agents on heavy metal extraction from contaminated soils. Res. J. Chem. Sci. 2014, 4, 70–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dipu, S.; Kumar, A.A.; Thanga, S.G. Effect of chelating agents in phytoremediation of heavy metals. Remediat. J. 2012, 22, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volf, I.; Stingu, A.; Popa, V.I. New natural chelating agents with modulator effects on copper phytoextraction. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2012, 11, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Ali, A.; Ren, C.; Du, J.; Li, R.; Lahori, A.H.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z. EDTA and organic acids assisted phytoextraction of Cd and Zn from a smelter contaminated soil by potherb Indian mustard (Brassica juncea, Coss) and evaluation of its bioindicators. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 167, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.A.; Piotto, F.A.; Nogueirol, R.C.; Azevedo, R.A. Use of non-hyperaccumulator plant species for the phytoextraction of heavy metals using chelating agents. Sci. Agric. 2013, 70, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, H.; Nisar, N.; Mehmood, S.; Iqbal, M.; Nazir, A.; Yasir, M. Indian mustard Brassica juncea efficiency for the accumulation, tolerance and translocation of zinc from metal contaminated soil. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 23, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinniaee, S.; Jafari, M.; Tavili, A.; Zare, S.; Cappai, G. Chelate facilitated phytoextraction of Pb, Cd, and Zn from a lead-zinc mine contaminated soil by three accumulator plants. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, S. Toxic metal accumulation, responses to exposure and mechanisms of tolerance in plants. Biochimie 2006, 88, 1707–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghori, N.H.; Ghori, T.; Hayat, M.Q.; Imadi, S.R.; Gul, A.; Altay, V.; Ozturk, M. Heavy metal stress and responses in plants. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 1807–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.H.; Luo, Y.M.; Xing, X.R.; Christie, P. EDTA-enhanced phytoremediation of heavy metal contaminated soil with Indian mustard and associated potential leaching risk. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 102, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowack, B. Environmental chemistry of aminopolycarboxylate chelating agents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 4009–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Yuan, M.; Huang, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Duan, C. Effects of Heavy Metals on Stomata in Plants: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Rasool, S.; Azooz, M.M.; Hossain, M.A.; Ahanger, M.A.; Ahmad, P. Chapter 24—Heavy Metal Stress: Plant Responses and Signaling; Ahmad, P., Ed.; Plant Metal Interaction; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 557–583. ISBN 9780128031582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epelde, L.; Hernández-Allica, J.; Becerril, J.M.; Blanco, F.; Garbisu, C. Effects of chelates on plants and soil microbial community: Comparison of EDTA and EDDS for lead phytoextraction. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 401, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Sung, K. Effects of chelates on soil microbial properties, plant growth and heavy metal accumulation in plant. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 73, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceló, J.; Poschenrieder, C. Plant water relations as affected by heavy metal stress: A review. J. Plant Nutr. 1990, 13, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, A.L.; Gussman, C.D.; Blaylock, M.J.; Yermiyahu, U.; Huang, J.W.; Kapulnik, Y.; Orser, C.S. EDTA and Pb—EDTA accumulation in Brassica juncea grown in Pb—Amended soil. Plant Soil 1999, 208, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaylock, M.J.; Salt, D.E.; Dushenkov, S.; Zakharova, O.; Gussman, C.; Kapulnik, Y.; Ensley, B.D.; Raskin, I. Enhanced accumulation of Pb in Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) by soil-applied chelating agents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1997, 31, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Baldwin, L.A. Hormesis: The dose-response revolution. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2003, 43, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Cózatl, D.G.; Jobe, T.O.; Hauser, F.; Schroeder, J.I. Long-distance transport, vacuolar sequestration, tolerance, and transcriptional responses induced by cadmium and arsenic. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 10th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Udeigwe, T.K.; Eze, P.N.; Teboh, J.M.; Stietiya, M.H. Application, chemistry, and environmental implications of contaminant-immobilization amendments on agricultural soil and water quality. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowack, B.; VanBriesen, J.M. Chelating agents in the environment. In Biogeochemistry of Chelating Agents; Nowack, B., VanBriesen, J.M., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbisu, C.; Alkorta, I. Phytoextraction: A cost-effective plant-based technology for the removal of metals from the environment. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 77, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, R.; Walker, D.J.; Bernal, M.P. Uptake of heavy metals and As by Brassica juncea grown in a contaminated soil in Aznalcóllar (Spain): The effect of soil amendments. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 138, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeremski, T.; Ranđelović, D.; Jakovljević, K.; Marjanović Jeromela, A.; Milić, S. Brassica Species in Phytoextractions: Real Potentials and Challenges. Plants 2021, 10, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; Zu, Y. Response of Cd, Zn Translocation and Distribution to Organic Acids Heterogeneity in Brassica juncea L. Plants 2023, 12, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.H.; Ali, S.; Kamran, M.; Iqbal, N.; Azeem, M.; Tariq Javed, M.; Ali, Q.; Zulqurnain Haider, M.; Irshad, S.; Rizwan, M. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA) Mitigates the Toxic Effect of Excessive Copper Concentrations on Growth, Gaseous Exchange and Chloroplast Ultrastructure of Corchorus capsularis L. and Improves Copper Accumulation Capabilities. Plants 2020, 9, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathika, R.; Srinivasan, P.; Alkahtani, J.; Al-Humaid, L.A.; Alwahibi, M.S.; Mythili, R.; Selvankumar, T. Influence of biochar and EDTA on enhanced phytoremediation of lead-contaminated soil by Brassica juncea. Chemosphere 2021, 271, 129513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saman, R.U.; Shahbaz, M.; Maqsood, M.F.; Lili, N.; Zulfiqar, U.; Haider, F.U.; Naz, N.; Shahzad, B. Foliar Application of Ethylenediamine Tetraacetic Acid (EDTA) Improves the Growth and Yield of Brown mustard (Brassica juncea) by Modulating Photosynthetic Pigments, Antioxidant Defense, and Osmolyte Production under Lead (Pb) Stress. Plants 2023, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloway, B.J. Heavy Metals in Soils: Trace Metals and Metalloids in Soils and Their Bioavailability, 3rd ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013; Volume 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabata-Pendias, A. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, M.B. Environmental Chemistry of Soils; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Shen, Z.; Li, X.; Baker, A.J. Enhanced phytoextraction of Pb and other metals from artificially contaminated soils through the combined application of EDTA and EDDS. Chemosphere 2006, 63, 1773–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriano, D.C. Trace Elements in Terrestrial Environments: Biogeochemistry, Bioavailability and Risks of Metal, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001; p. 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, J.; Khorasani, N.; Lorestani, B.; Karami, M.; Hassani, A.H.; Yousefi, N. Accumulation of heavy metals in soil and uptake by plant species with phytoremediation potential. Environ. Earth. Sci. 2009, 59, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Cui, J.; Tang, B.; Yang, L. Chelant-Induced Phytoextraction of Heavy Metals from Contaminated Soils: A Review. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2018, 27, 2417–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Sajad, M.A. Phytoremediation of heavy metals—Concepts and applications. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, N.; Imran, M.; Shaheen, M.R.; Ishaque, W.; Kamran, M.A.; Matloob, A.; Rehim, A.; Hussain, S. Phytore-mediation strategies for soils contaminated with heavy metals: Modifications and future perspectives. Chemosphere 2017, 171, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Abiotic Stress: Revisiting the Crucial Role of a Universal Defense Regulator. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Jha, A.; Dubey, R.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 2012, 217037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.J.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, Y.G.; Tang, Z.; McGrath, S.P. Soil contamination in China: Current status and mitigation strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassil, A.D.; Kapulnik, Y.; Raskin, I.; Salt, D.E. The Role of EDTA in Lead Transport and Accumulation by Indian mustard. Plant Physiol. 1998, 117, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K. Heavy metals toxicity in plants: An overview on the role of glutathione and phytochelatins in heavy metal stress tolerance of plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2010, 76, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagajyoti, P.C.; Lee, K.D.; Sreekanth, T.V.M. Heavy metals, occurrence and toxicity for plants: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2010, 8, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metal | Salt Used | Metal Content in Salt, % | Total Quantity, g | Quantity Per Pot, g | Water Used, L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn | ZnSO4·7H2O | 22.75 | 488.3 | 17.44 | 5 |

| Cu | CuSO4·5H2O | 25.44 | 235.2 | 8.40 | 5 |

| Pb | Pb(CH3COO)2·3H2O | 64.3 | 26.54 | 0.948 | 2 |

| Treatment | Concentration of the Solution EDTA (mmol·L−1) | Content EDTA (g·L−1) | Dosage per Application (mmol/pot) | Cumulative Dose (mmol/pot) | Equivalent (mmol·kg−1 Dry Soil) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDTA 1 | 15.625 | 5.816 | 0.0625 | 0.75 | 0.5 |

| EDTA 2 | 31.250 | 11.633 | 0.1250 | 1.50 | 1.0 |

| EDTA 3 | 62.500 | 23.265 | 0.2500 | 3.00 | 2.0 |

| Type of Treatment | Mean ± SD of Soil Metal Content and Tukey Grouping *, (mg·kg−1) | Percentage of Metal Reduction After Soil Decontamination, (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn | Cu | Pb | Zn | Cu | Pb | |

| Untreated contaminated soil | 993.0 ± NA (a) | 534.0 ± NA (a) | 152.0 ± NA (a) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Only Indian mustard | 951.0 ± NA (b) | 496.0 ± NA (b) | 134.0 ± NA (b) | 4.2 | 7.1 | 11.8 |

| EDTA 0.5 mmol·kg−1 (EDTA 1) | 786.5 ± 4.2 (c) | 445.5 ± 2.4 (c) | 129.8 ± 1.7 (b) | 20.8 | 16.6 | 14.6 |

| EDTA 1.0 mmol·kg−1 (EDTA 2) | 778.8 ± 2.6 (c) | 432.0 ± 2.4 (d) | 126.0 ± 2.9 (b) | 21.6 | 19.1 | 17.1 |

| EDTA 2.0 mmol·kg−1 (EDTA 3) | 761.0 ± 2.6 (d) | 425.5 ± 1.3 (e) | 119.8 ± 3.1 (c) | 23.4 | 20.3 | 21.2 |

| Indian mustard and EDTA 0.5 mmol·kg−1 (EDTA 1) | 672.5 ± 11.2 (e) | 395.5 ± 2.1 (f) | 119.0 ± 1.8 (c) | 32.3 | 25.9 | 21.7 |

| Indian mustard and EDTA 1.0 mmol·kg−1 (EDTA 2) | 568.2 ± 4.3 (f) | 393.0 ± 1.8 (f) | 104.8 ± 0.5 (d) | 42.8 | 26.4 | 31.1 |

| Indian mustard and EDTA 2.0 mmol·kg−1 (EDTA 3) | 481.8 ± 2.4 (g) | 387.2 ± 2.5 (g) | 96.8 ± 1.7 (e) | 51.5 | 27.5 | 36.3 |

| Type of Metal | a (Slope) | b (Intercept) | R2 | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal content (mg·kg−1) | ||||

| Cu | −73.79 | 536.41 | 0.98 | Strong decrease, excellent model (98%) |

| Zn | −232.1 | 1056.7 | 0.88 | Strong decrease, very good model |

| Pb | −23.26 | 153.61 | 0.91 | Steady decrease, stable model |

| Percentage loss (%) | ||||

| Cu | 10.34 | 7.8211 | 0.97 | Progressive loss, very strong correlation |

| Zn | 21.337 | 2.1002 | 0.87 | Accelerated loss, very good model |

| Pb | 11.469 | 8.0041 | 0.79 | Moderate loss, good fit |

| Treatment Type | Mobilization Factor (MF) of Heavy Metals | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Zn | Cu | Pb | |

| Contaminated soil | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Only Indian mustard | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.88 |

| EDTA 0.5 mmol·kg−1 (EDTA 1) | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.85 |

| EDTA 1.0 mmol·kg−1 (EDTA 2) | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.83 |

| EDTA 2.0 mmol·kg−1 (EDTA 3) | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.79 |

| Indian mustard and EDTA 0.5 mmol·kg−1 (EDTA 1) | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.78 |

| Indian mustard and EDTA 1.0 mmol·kg−1 (EDTA 2) | 0.57 | 0.74 | 0.69 |

| Indian mustard and EDTA 2.0 mmol·kg−1 (EDTA 3) | 0.49 | 0.72 | 0.64 |

| Heavy Metal | Parameter | F-Value | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu (a) | Fresh weight, (g/plant) | F = 6.315 | p = 0.0081 | ** |

| Chlorophyll content, (SPAD units) | F = 1.797 | p = 0.2013 | ns | |

| Plant moisture, (%) | F = 2.610 | p = 0.0996 | ns | |

| Plant height, (cm) | F = 98.532 | p < 0.0001 | *** | |

| Zn (b) | Fresh weight, (g/plant) | F = 7.155 | p = 0.0052 | ** |

| Chlorophyll content, (SPAD units) | F = 3.076 | p = 0.0686 | ns | |

| Plant moisture, (%) | F = 2.435 | p = 0.1152 | ns | |

| Plant height, (cm) | F = 53.966 | p < 0.0001 | *** | |

| Pb (c) | Fresh weight, (g/plant) | F = 14.419 | p = 0.0003 | *** |

| Chlorophyll content, (SPAD units) | F = 0.403 | p = 0.7537 | ns | |

| Plant moisture, (%) | F = 21.705 | p < 0.0001 | *** | |

| Plant height, (cm) | F = 160.526 | p < 0.0001 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pruteanu, A.; Nițu, M.; Vlăduț, V.; Matache, M.; Voicea, I.; Iuliana, G.; Vanghele, N.; Nenciu, F.; Cujbescu, D.; Badea, D.O. Induced Phytoextraction of Heavy Metals from Soils Using Brassica juncea and EDTA: An Efficient Approach to the Remedy of Zinc, Copper and Lead. Environments 2026, 13, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010023

Pruteanu A, Nițu M, Vlăduț V, Matache M, Voicea I, Iuliana G, Vanghele N, Nenciu F, Cujbescu D, Badea DO. Induced Phytoextraction of Heavy Metals from Soils Using Brassica juncea and EDTA: An Efficient Approach to the Remedy of Zinc, Copper and Lead. Environments. 2026; 13(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010023

Chicago/Turabian StylePruteanu, Augustina, Mihaela Nițu, Valentin Vlăduț, Mihai Matache, Iulian Voicea, Gageanu Iuliana, Nicoleta Vanghele, Florin Nenciu, Dan Cujbescu, and Daniel Onuț Badea. 2026. "Induced Phytoextraction of Heavy Metals from Soils Using Brassica juncea and EDTA: An Efficient Approach to the Remedy of Zinc, Copper and Lead" Environments 13, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010023

APA StylePruteanu, A., Nițu, M., Vlăduț, V., Matache, M., Voicea, I., Iuliana, G., Vanghele, N., Nenciu, F., Cujbescu, D., & Badea, D. O. (2026). Induced Phytoextraction of Heavy Metals from Soils Using Brassica juncea and EDTA: An Efficient Approach to the Remedy of Zinc, Copper and Lead. Environments, 13(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010023