Interactive Effects of Laminaria digitata Supplementation and Heatwave Events on Farmed Gilthead Seabream Antioxidant Status, Digestive Activity, and Lipid Metabolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Diets

2.2. Organisms and Experimental Design

2.3. Biochemical Analysis

2.3.1. Oxidative Stress

2.3.2. Digestive Enzymes

2.3.3. Fatty Acid Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

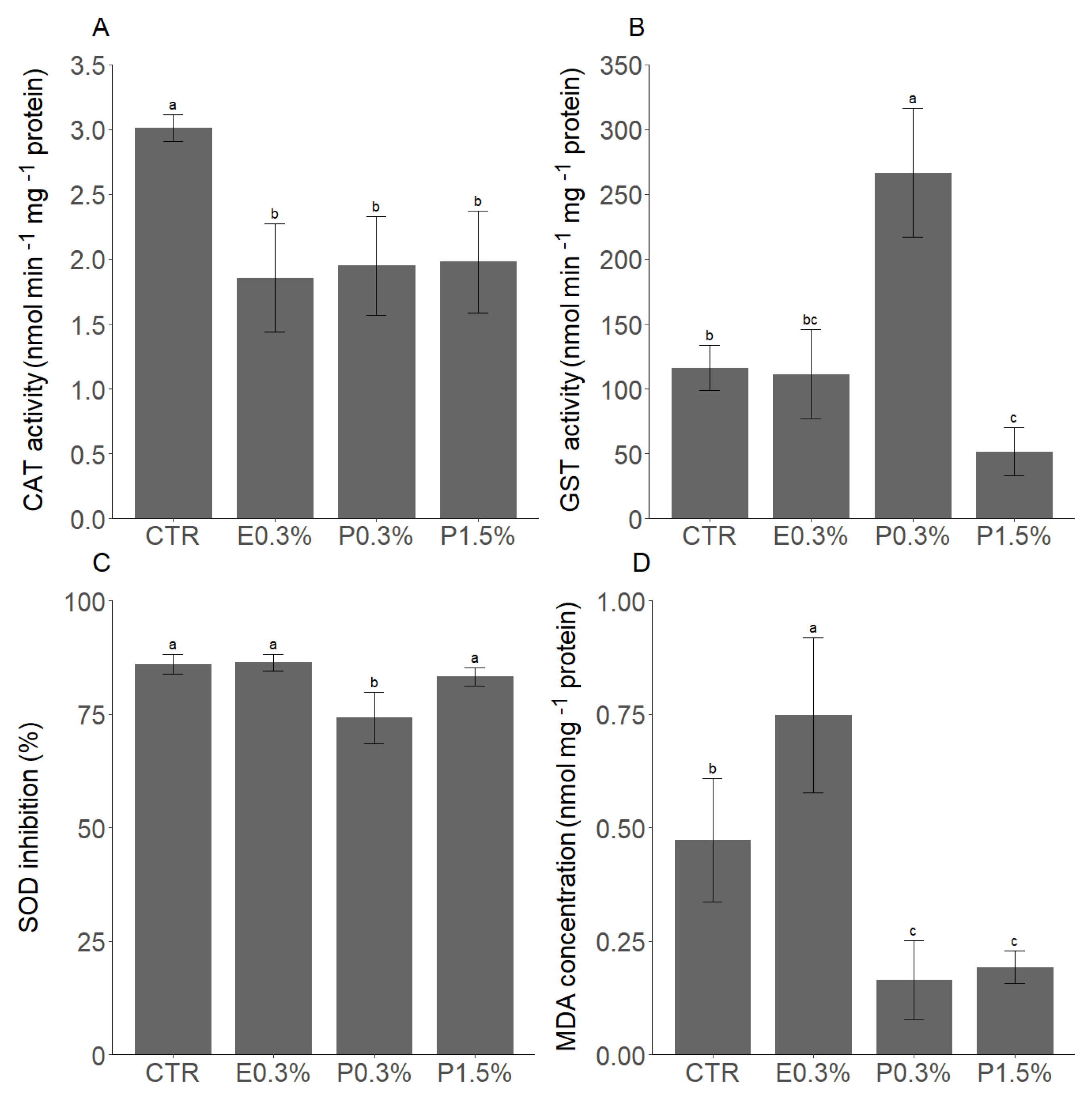

3.1. The Effects of L. digitata Supplementation Under Control Temperature Conditions

| CTR | E0.3% | P0.3% | P1.5% | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14:0 | 2.61 ± 0.43 | 2.63 ± 0.24 | 2.45 ± 0.16 | 2.93 ± 0.07 | 0.372 |

| 16:0 | 14.69 ± 0.50 | 16.52 ± 0.35 | 16.30 ± 1.06 | 15.79 ± 0.19 | 0.150 |

| 18:0 | 5.30 ± 0.90 | 5.23 ± 0.07 | 5.38 ± 0.31 | 5.15 ± 0.53 | 0.797 |

| ΣSFA | 24.51 ± 1.27 | 26.15 ± 0.33 | 25.61 ± 0.84 | 25.36 ± 0.28 | 0.313 |

| 16:1 n-7 | 4.43 ± 0.57 | 3.71 ± 0.03 | 3.82 ± 0.32 | 4.45 ± 0.03 | 0.120 |

| 18:1 n-7 | 3.13 ± 0.11 | 2.63 ± 0.05 | 2.79 ± 0.21 | 2.93 ± 0.12 | 0.058 |

| 18:1 n-9 | 22.64 ± 3.08 | 17.14 ± 0.67 | 18.64 ± 2.24 | 21.43 ± 0.60 | 0.155 |

| 20:1 n-9 | 1.20 ± 0.37 | 1.10 ± 0.01 | 1.07 ± 0.09 | 1.43 ± 0.06 | 0.430 |

| ΣMUFA | 33.62 ± 3.81 | 26.46 ± 0.85 | 28.21 ± 3.10 | 32.39 ± 0.46 | 0.113 |

| 18:2 n-6 | 11.41 ± 1.60 | 10.28 ± 0.10 | 10.66 ± 0.43 | 11.43 ± 0.65 | 0.451 |

| 18:3 n-3 | 2.19 ± 0.46 | 1.95 ± 0.06 | 1.97 ± 0.12 | 2.18 ± 0.18 | 0.599 |

| 20:4 n-6 | 1.33 ± 0.36 | 2.01 ± 0.02 | 1.78 ± 0.31 | 1.37 ± 0.11 | 0.130 |

| 20:5 n-3 | 5.85 ± 0.97 | 7.22 ± 0.28 | 6.62 ± 1.05 | 5.73 ± 0.01 | 0.186 |

| 22:5 n-3 | 2.38 ± 0.36 | 2.70 ± 0.24 | 2.79 ± 0.34 | 2.65 ± 0.64 | 0.623 |

| 22:6 n-3 | 10.29 ± 2.63 | 15.38 ± 0.16 | 14.70 ± 1.94 | 10.90 ± 0.02 | 0.121 |

| ΣPUFA | 37.75 ± 2.29 | 43.70 ± 0.43 | 42.49 ± 2.12 | 33.22 ± 7.20 | 0.106 |

| ΣPUFA n-3 | 22.84 ± 3.41 | 29.21 ± 0.56 | 27.98 ± 2.16 | 23.47 ± 0.41 | 0.097 |

| ΣPUFA n-6 | 14.16 ± 1.25 | 13.82 ± 0.13 | 13.86 ± 0.27 | 14.03 ± 0.52 | 0.867 |

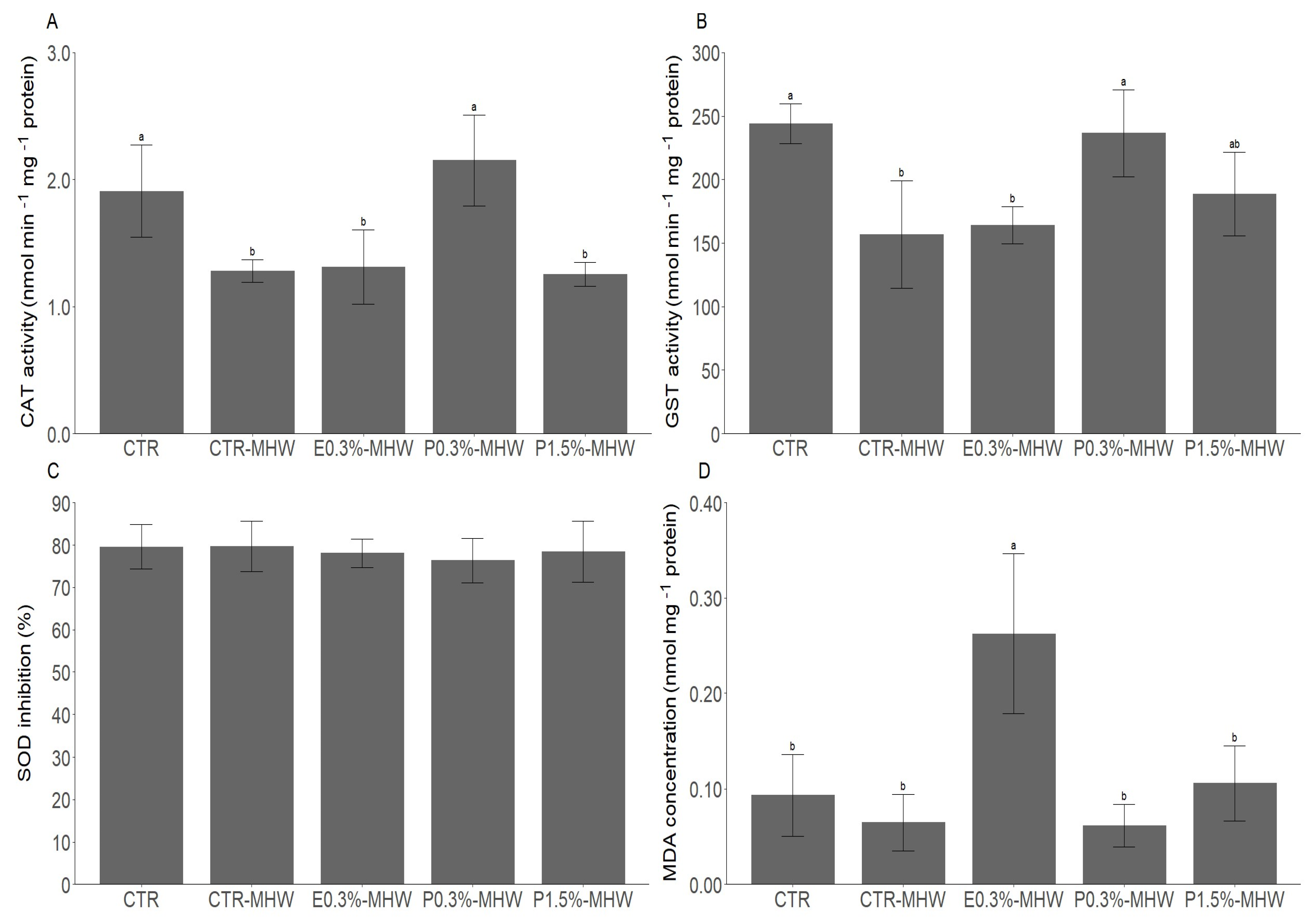

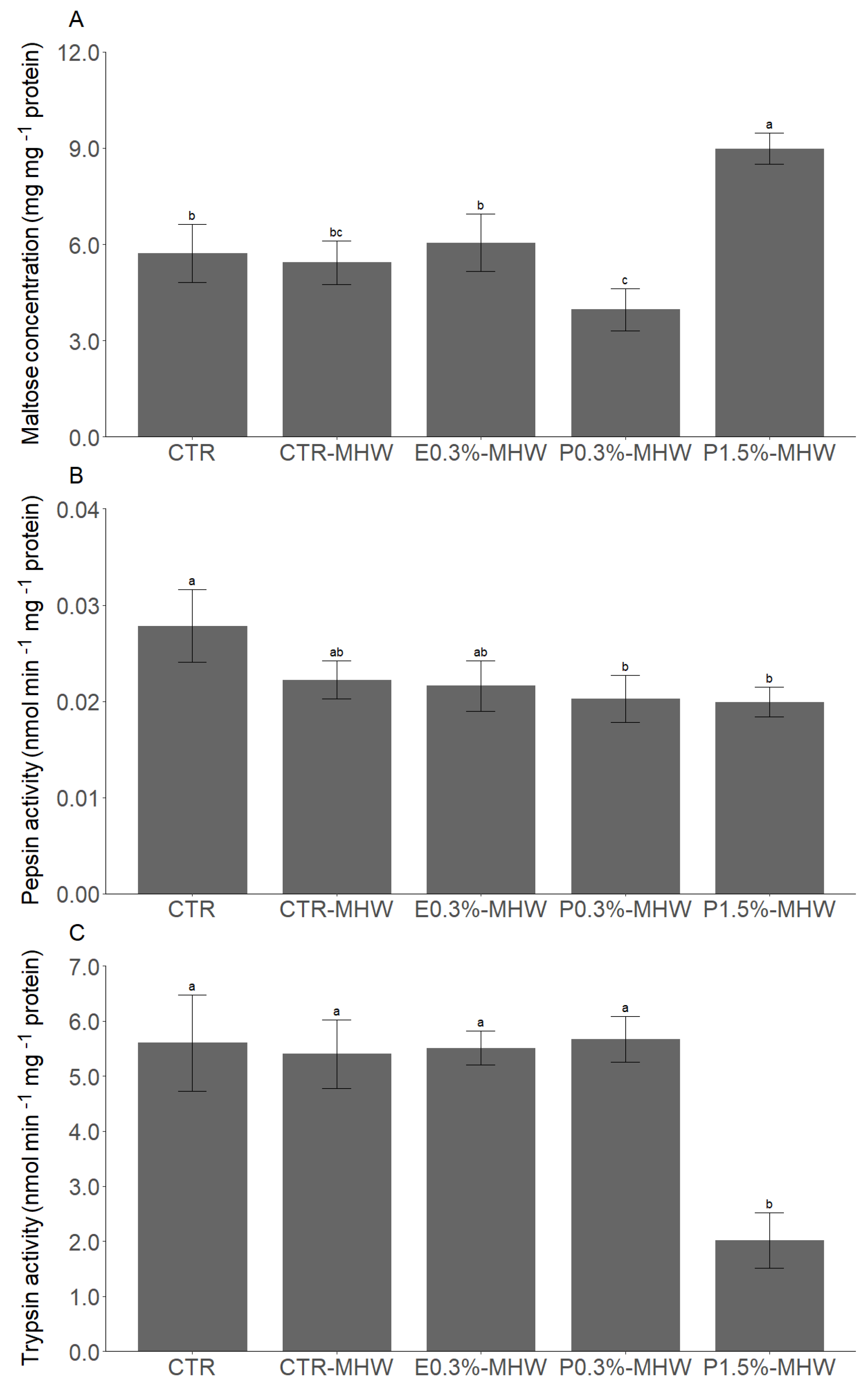

3.2. The Effects of L. digitata Supplementation upon MHW Exposure

| CTR | CTR-HW | E0.3%-HW | P0.3%-HW | P1.5%-HW | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14:0 | 2.83 ± 0.21 | 2.23 ± 0.11 | 2.82 ± 0.42 | 2.75 ± 0.23 | 2.40 ± 0.30 | 0.095 |

| 16:0 | 15.63 ± 0.48 b | 16.72 ± 0.29 ab | 15.76 ± 1.04 ab | 16.61 ± 0.36 ab | 17.86 ± 0.46 a | 0.033 |

| 18:0 | 5.20 ± 0.61 ab | 6.06 ± 0.13 a | 4.90 ± 0.19 b | 4.86 ± 0.33 ab | 5.70 ± 0.19 ab | 0.039 |

| ΣSFA | 23.59 ± 0.55 ab | 24.85 ± 0.05 ab | 22.63 ± 0.34 ab | 23.11 ± 0.96 b | 25.11 ± 0.52 a | 0.026 |

| 16:1 n-7 | 4.41 ± 0.08 a | 3.50 ± 0.14 b | 4.13 ± 0.44 ab | 4.06 ± 0.01 ab | 3.47 ± 0.39 b | 0.012 |

| 18:1 n-7 | 2.91 ± 0.09 | 2.62 ± 0.04 | 2.76 ± 0.29 | 2.59 ± 0.12 | 2.42 ± 0.21 | 0.127 |

| 18:1 n-9 | 21.32 ± 1.92 | 17.94 ± 0.59 | 19.25 ± 1.88 | 18.65 ± 0.13 | 16.83 ± 1.40 | 0.050 |

| 20:1 n-9 | 1.29 ± 0.28 | 1.05 ± 0.10 | 1.12 ± 0.88 | 1.09 ± 0.04 | 0.96 ± 0.16 | 0.437 |

| ΣMUFA | 32.11 ± 2.22 | 27.29 ± 0.93 | 28.95 ± 2.95 | 28.20 ± 0.36 | 25.51 ± 2.28 | 0.067 |

| 18:2 n-6 | 10.91 ± 0.65 a | 9.63 ± 0.25 b | 11.01 ± 0.13 a | 10.96 ± 0.34 ab | 9.64 ± 0.55 b | 0.005 |

| 18:3 n-3 | 2.13 ± 0.21 ab | 1.80 ± 0.05 ab | 2.12 ± 0.07 a | 2.16 ± 0.21 ab | 1.69 ± 0.11 b | 0.033 |

| 20:4 n-6 | 1.36 ± 0.27 b | 1.92 ± 0.05 ab | 1.53 ± 0.28 ab | 1.61 ± 0.0 ab | 2.06 ± 0.24 a | 0.019 |

| 20:5 n-3 | 5.54 ± 0.64 | 6.72 ± 0.45 | 6.12± 0.40 | 6.55 ± 0.62 | 6.24 ± 0.39 | 0.147 |

| 22:5 n-3 | 2.29 ± 0.20 | 2.39 ± 0.12 | 2.67 ± 0.23 | 2.51 ± 0.13 | 1.28 ± 0.17 | 0.081 |

| 22:6 n-3 | 11.71 ± 1.49 | 16.70 ± 0.36 | 14.83 ± 3.18 | 15.32 ± 1.14 | 18.89 ±2.70 | 0.057 |

| ΣPUFA | 38.33 ± 2.09 | 42.89 ± 0.36 | 42.45 ± 3.12 | 42.92 ± 2.05 | 44.05 ± 2.44 | 0.168 |

| ΣPUFA n-3 | 23.85 ± 2.18 | 29.43 ± 0.42 | 27.83 ± 3.06 | 28.52 ± 1.84 | 30.64 ± 2.73 | 0.123 |

| ΣPUFA n-6 | 13.77 ± 0.29 a | 12.94 ± 0.09 b | 13.94 ± 0.16 a | 13.79 ± 0.22 a | 12.97 ± 0.31 b | <0.001 |

4. Discussion

4.1. L. digitata Supplementation Under Control Temperature Conditions

4.2. L. digitata Supplementation upon MHW Exposure

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-138763-4. [Google Scholar]

- Da Fonseca Ferreira, A.; Roquigny, R.; Grard, T.; Le Bris, C. Temporal and Spatial Dynamics of Vibrio Harveyi: An Environmental Parameter Correlation Investigation in a 4-Metre-Deep Dicentrarchus labrax Aquaculture Tank. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, A.C.; Andrade, C.; Matias, A.C.; Andrade, C. New Challenges in Marine Aquaculture Research. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Abramo, L.R. Realizing the Potential of Aquaculture: Undertaking the Wicked Problems of Climate Change, Fed Production Systems and Global Food Security. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2025, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobday, A.J.; Alexander, L.V.; Perkins, S.E.; Smale, D.A.; Straub, S.C.; Oliver, E.C.J.; Benthuysen, J.A.; Burrows, M.T.; Donat, M.G.; Feng, M.; et al. A Hierarchical Approach to Defining Marine Heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 2016, 141, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Austin, C.; Lake, I.; Archer, E.; Hartnell, R.; Trinanes, J.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Stemming the Rising Tide of Vibrio Disease. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e515–e520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalah, J.; Ibañez, S.; Aixalà, L.; Barber, X.; Sánchez-Jerez, P. Marine Heatwaves in the Western Mediterranean: Considerations for Coastal Aquaculture Adaptation. Aquaculture 2024, 588, 740917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharsack, J.P.; Franke, F. Temperature Effects on Teleost Immunity in the Light of Climate Change. J. Fish Biol. 2022, 101, 780–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Peng, Y.; Xu, Y.; He, G.; Liang, J.; Masanja, F.; Yang, K.; Xu, X.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, L. Responses of Digestive Metabolism to Marine Heatwaves in Pearl Oysters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 186, 114395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siboni, N.; King, W.L.; Williams, N.L.R.; Scanes, E.; Giardina, M.; Green, T.J.; Ostrowski, M.; O’Connor, W.; Dove, M.; Labbate, M.; et al. Increased Abundance of Potentially Pathogenic Vibrio and a Marine Heatwave Co-Occur with a Pacific Oyster Summer Mortality Event. Aquaculture 2024, 583, 740618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmaraki, S.; Somot, S.; Sevault, F.; Nabat, P. Past Variability of Mediterranean Sea Marine Heatwaves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 9813–9823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, H.; McAdam, R.; Juza, M.; Masina, S.; Speich, S. Marine Heat Waves in the Mediterranean Sea: An Assessment from the Surface to the Subsurface to Meet National Needs. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1045138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, M.F.; Mazlum, Y. Global Warming and Sustainable Aquaculture in Türkiye: The Case of Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) and Gilthead Sea Bream (Sparus aurata). Aquacult Int. 2025, 33, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrakidis-Zachou, O.; Lika, K.; Anastasiadis, P.; Papandroulakis, N. Projecting Climate Change Impacts on Mediterranean Finfish Production: A Case Study in Greece. Clim. Change 2021, 165, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmelo, I.; Chainho, T.; Bolotas, D.; Pereira, A.; Özkan, B.; Marques, C.; Silva, I.A.L.; Soares, F.; Pousão-Ferreira, P.; Vieira, E.F.; et al. Laminaria digitata Supplementation as a Climate-Smart Strategy to Counteract the Interactive Effects of Marine Heatwaves and Disease Outbreaks in Farmed Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata). Environments 2025, 12, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciji, A.; Akhtar, M.S. Stress Management in Aquaculture: A Review of Dietary Interventions. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 2190–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacon, A.G.J.; Metian, M.; McNevin, A.A. Future Feeds: Suggested Guidelines for Sustainable Development. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2022, 30, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, A.; Pérez, J.A.; Martín, V.; Acosta, N.G.; Reis, D.B.; Jiménez, I.A.; Rosa, G.; Venuleo, M.; Marrero, M.; Rodríguez, C. Effect of Feed Supplementation with Seaweed Wracks on Performance, Muscle Lipid Composition, Antioxidant Status, Digestive Enzyme Activities, and Plasma Biochemistry of Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata) Juveniles. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 31, 101673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Tawwab, M.; Harikrishnan, R.; Devi, G.; Bhat, E.A.; Paray, B.A. Stimulatory Effects of Seaweed Laminaria digitata Polysaccharides Additives on Growth, Immune-Antioxidant Potency and Related Genes Induction in Rohu Carp (Labeo rohita) during Flavobacterium columnare Infection. Aquaculture 2024, 579, 740253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunathilake, T.; Akanbi, T.O.; Suleria, H.A.R.; Nalder, T.D.; Francis, D.S.; Barrow, C.J. Seaweed Phenolics as Natural Antioxidants, Aquafeed Additives, Veterinary Treatments and Cross-Linkers for Microencapsulation. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwendwa, R.; Wawire, M.; Kahenya, P. Potential for Use of Seaweed as a Fish Feed Ingredient: A Review. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 15, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Latif, H.M.R.; Dawood, M.A.O.; Alagawany, M.; Faggio, C.; Nowosad, J.; Kucharczyk, D. Health Benefits and Potential Applications of Fucoidan (FCD) Extracted from Brown Seaweeds in Aquaculture: An Updated Review. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 122, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Mawla, M.S.; Magouz, F.I.; Khalafalla, M.M.; Amer, A.A.; Soliman, A.A.; Zaineldin, A.I.; Gewaily, M.S.; Dawood, M.A.O. Growth Performance, Intestinal Morphology, Blood Biomarkers, and Immune Response of Thinlip Grey Mullet (Liza ramada) Fed Dietary Laminarin Supplement. J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.; López-Alonso, M.; García-Vaquero, M. Macroalgae for Functional Feed Development: Applications in Aquaculture, Ruminant and Swine Feed Industries. In Seaweeds: Biodiversity, Environmental Chemistry and Ecological Impacts; Newton, P., Ed.; NOVA, Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A.; Marmelo, I.; Dias, M.; Silva, A.C.; Grade, A.C.; Barata, M.; Pousão-Ferreira, P.; Dias, J.; Anacleto, P.; Marques, A.; et al. Asparagopsis Taxiformis as a Novel Antioxidant Ingredient for Climate-Smart Aquaculture: Antioxidant, Metabolic and Digestive Modulation in Juvenile White Seabream (Diplodus sargus) Exposed to a Marine Heatwave. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmelo, I.; Dias, M.; Grade, A.; Pousão-Ferreira, P.; Diniz, M.S.; Marques, A.; Maulvault, A.L. Immunomodulatory and Antioxidant Effects of Functional Aquafeeds Biofortified with Whole Laminaria digitata in Juvenile Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata). Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1325244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.; Marmelo, I.; Chainho, T.; Bolotas, D.; Dias, M.; Cereja, R.; Barata, M.; Pousão-Ferreira, P.; Vieira, E.F.; Delerue-Matos, C.; et al. Improving Farmed Juvenile Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata) Stress Response to Marine Heatwaves and Vibriosis Through Seaweed-Based Dietary Modulation. Animals 2025, 15, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell-Meyerink, D.; Packer, M.A.; Wheeler, T.T.; Hayes, M. Aquaculture Production of the Brown Seaweeds Laminaria digitata and Macrocystis pyrifera: Applications in Food and Pharmaceuticals. Molecules 2021, 26, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palstra, A.P.; Kals, J.; Blanco Garcia, A.; Dirks, R.P.; Poelman, M. Immunomodulatory Effects of Dietary Seaweeds in LPS Challenged Atlantic Salmon Salmo salar as Determined by Deep RNA Sequencing of the Head Kidney Transcriptome. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamunde, C.; Sappal, R.; Melegy, T.M. Brown Seaweed (AquaArom) Supplementation Increases Food Intake and Improves Growth, Antioxidant Status and Resistance to Temperature Stress in Atlantic Salmon, Salmo salar. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, L.H.; Håkan Borg, L.A. A Spectrophotometric Method for Determination of Catalase Activity in Small Tissue Samples. Anal. Biochem. 1988, 174, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habig, W.H.; Pabst, M.J.; Jakoby, W.B. Glutathione S-Transferases. J. Biol. Chem. 1974, 249, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Oberley, L.W.; Li, Y. A Simple Method for Clinical Assay of Superoxide Dismutase. Clin. Chem. 1988, 34, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, M.; Mihara, M. Determination of Malonaldehyde Precursor in Tissues by Thiobarbituric Acid Test. Anal. Biochem. 1978, 86, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaharudin, N.; Salmeán, A.A.; Dragsted, L.O. Inhibitory Effects of Edible Seaweeds, Polyphenolics and Alginates on the Activities of Porcine Pancreatic α-Amylase. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anson, M.L. The Estimation Of Pepsin, Trypsin, Papain and Cathepsin With Hemoglobin. J. Gen. Physiol. 1938, 22, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comabella, Y.; Mendoza, R.; Aguilera, C.; Carrillo, O.; Hurtado, A.; García-Galano, T. Digestive Enzyme Activity during Early Larval Development of the Cuban Gar Atractosteus tristoechus. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 2006, 32, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlanger, B.F.; Kokowsky, N.; Cohen, W. The Preparation and Properties of Two New Chromogenic Substrates of Trypsin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1961, 95, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomklao, S.; Benjakul, S.; Visessanguan, W.; Kishimura, H.; Simpson, B. Proteolytic Degradation of Sardine (Sardinella gibbosa) Proteins by Trypsin from Skipjack Tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) Spleen. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarra, N.M.; Batista, I.; Nunes, M.L.; Empis, J.M.; Christie, W.W. Seasonal Changes in Lipid Composition of Sardine (Sardina pilchardus). J. Food Sci. 1997, 62, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Antequera, F.P.; Simó-Mirabet, P.; Román, M.; Fuentes, J.; Oliva, M.; Méndez-Paz, D.; Vázquez-Sobrado, R.; Martos-Sitcha, J.A.; Moyano, F.J.; Mancera, J.M. Effect of Algal Extracts on the Metabolism, Intestinal Functionality and Oxidative Status of Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata). Aquaculture 2025, 609, 742869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, D.; Vinagre, C.; Diniz, M.S. Are Fish in Hot Water? Effects of Warming on Oxidative Stress Metabolism in the Commercial Species Sparus aurata. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 63, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Li, W.; Lin, Q.; Lin, X.; Lin, J.; Zhu, Q.; Jiang, H.; Huang, Z. Dietary Administration of Laminarin Improves the Growth Performance and Immune Responses in Epinephelus coioides. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014, 41, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, S.; Cai, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, D.; Guo, W.; Wang, S. Effects of Five Prebiotics on Growth, Antioxidant Capacity, Non-Specific Immunity, Stress Resistance, and Disease Resistance of Juvenile Hybrid Grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂). Animals 2023, 13, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.; Marmelo, I.; Dias, M.; Anacleto, P.; Pires, C.; Batista, I.; Marques, A.; Maulvault, A.L. Antioxidant, Metabolic and Digestive Biomarker Responses of Farmed Sparus aurata Supplemented with Laminaria digitata. Aquaculture 2025, 598, 741984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negara, B.F.S.P.; Sohn, J.H.; Kim, J.-S.; Choi, J.-S. Effects of Phlorotannins on Organisms: Focus on the Safety, Toxicity, and Availability of Phlorotannins. Foods 2021, 10, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.J.; Svendsen, J.C.; Malte, H.; Pereira, L.F.; Carvalho, P.; Pereira, R.; Gonçalves, J.F.M.; Ozório, R.O.A. Diets Supplemented with Seaweed Affect Metabolic Rate, Innate Immune, and Antioxidant Responses, but Not Individual Growth Rate in European Seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 2061–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, I.; Magalhães, R.; Coutinho, F.; Couto, A.; Sousa, S.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Domingues, V.F.; Oliva-Teles, A.; Peres, H. Evaluation of the Seaweeds Chondrus crispus and Ulva lactuca as Functional Ingredients in Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata). J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 2115–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C.; Peréz-Jiménez, A.; Coutinho, F.; Díaz-Rosales, P.; Serra, C.A.D.R.; Panserat, S.; Corraze, G.; Peres, H.; Oliva-Teles, A. Dietary Carbohydrate and Lipid Sources Affect Differently the Oxidative Status of European Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) Juveniles. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 1584–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhzadeh, N.; Ahmadifar, E.; Soltani, M.; Tayefi-Nasrabadi, H.; Mousavi, S.; Naiel, M.A.E. Brown Seaweed (Padina australis) Extract Can Promote Performance, Innate Immune Responses, Digestive Enzyme Activities, Intestinal Gene Expression and Resistance against Aeromonas hydrophila in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio). Animals 2022, 12, 3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norambuena, F.; Hermon, K.; Skrzypczyk, V.; Emery, J.A.; Sharon, Y.; Beard, A.; Turchini, G.M. Algae in Fish Feed: Performances and Fatty Acid Metabolism in Juvenile Atlantic Salmon. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.J.; Salas-Leitón, E.; Pereira, L.F.; Queiroz, A.; Magalhães, F.; Pereira, R.; Abreu, H.; Reis, P.A.; Gonçalves, J.F.M.; Ozório, R.O.D.A. Role of Dietary Seaweed Supplementation on Growth Performance, Digestive Capacity and Immune and Stress Responsiveness in European Seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Aquac. Rep. 2016, 3, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcaíno, A.J.; Mendes, S.I.; Varela, J.L.; Ruiz-Jarabo, I.; Rico, R.; Figueroa, F.L.; Abdala, R.; Moriñigo, M.Á.; Mancera, J.M.; Alarcón, F.J. Growth, Tissue Metabolites and Digestive Functionality in Sparus aurata Juveniles Fed Different Levels of Macroalgae, Gracilaria cornea and Ulva rigida. Aquac. Res. 2016, 47, 3224–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkoff, H.; Rønnestad, I. Effects of Temperature on Feeding and Digestive Processes in Fish. Temperature 2020, 7, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdala-Díaz, R.T.; García-Márquez, J.; Rico, R.M.; Gómez-Pinchetti, J.L.; Mancera, J.M.; Figueroa, F.L.; Alarcón, F.J.; Martínez-Manzanares, E.; Moriñigo, M.Á. Effects of a Short Pulse Administration of Ulva rigida on Innate Immune Response and Intestinal Microbiota in Sparus aurata Juveniles. Aquac. Res. 2021, 52, 3038–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Tawwab, M.; Mousa, M.A.A.; Mamoon, A.; Abdelghany, M.F.; Abdel-Hamid, E.A.A.; Abdel-Razek, N.; Ali, F.S.; Shady, S.H.H.; Gewida, A.G.A. Dietary Chlorella vulgaris Modulates the Performance, Antioxidant Capacity, Innate Immunity, and Disease Resistance Capability of Nile Tilapia Fingerlings Fed on Plant-Based Diets. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2022, 283, 115181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho Ribeiro, A.; Gonçalves, A.; Colen, R.; Nunes, M.L.; Dinis, M.T.; Dias, J. Dietary Macroalgae Is a Natural and Effective Tool to Fortify Gilthead Seabream Fillets with Iodine: Effects on Growth, Sensory Quality and Nutritional Value. Aquaculture 2015, 437, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Huan, P.; Liu, B. The Combination of High Temperature and Vibrio Infection Worsens Summer Mortality in the Clam Meretrix petechialis by Increasing Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 149, 109542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.J.; Magnoni, L.; Gonçalves, J.F.M.; Twijnstra, R.H.; Kijjoa, A.; Pereira, R.; Palstra, A.P.; Ozório, R.O.A. Effects of Dietary Supplementation of Gracilaria Sp. Extracts on Fillet Quality, Oxidative Stress, and Immune Responses in European Seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Sun, X.; Li, N.; Guo, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wang, L. Structural Properties and Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides Extracted from Laminaria japonica Using Various Methods. Process Biochem. 2021, 111, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, V.; Maulvault, A.L.; Alves, R.N.; Anacleto, P.; Pousão-Ferreira, P.; Carvalho, M.L.; Nunes, M.L.; Rosa, R.; Marques, A. Will Seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) Quality Change in a Warmer Ocean? Food Res. Int. 2017, 97, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, K.; Zhang, R.; Luo, L.; Wang, S.; Xu, W.; Zhao, Z. Effects of Thermal Stress on the Antioxidant Capacity, Blood Biochemistry, Intestinal Microbiota and Metabolomic Responses of Luciobarbus capito. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tocher, D.R.; Fonseca-Madrigal, J.; Dick, J.R.; Ng, W.-K.; Bell, J.G.; Campbell, P.J. Effects of Water Temperature and Diets Containing Palm Oil on Fatty Acid Desaturation and Oxidation in Hepatocytes and Intestinal Enterocytes of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 137, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Ding, L.; Wei, X.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z.; Han, S.; Huang, T.; Wang, B.; et al. Physiological Responses to Heat Stress in the Liver of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Revealed by UPLC-QTOF-MS Metabolomics and Biochemical Assays. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 242, 113949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, H.; Maulvault, A.L.; Santos, C.P.; Silva, M.; Bandarra, N.M.; Valente, L.M.P.; Rosa, R.; Marques, A.; Anacleto, P. Can Marine Heatwaves Affect the Fatty Acid Composition and Energy Budget of the Tropical Fish Zebrasoma scopas? Environ. Res. 2023, 224, 115504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gomes, R.V.C.; Marmelo, I.; Chainho, T.; Pereira, A.; Bolotas, D.; Barata, M.; Pousão-Ferreira, P.; Vieira, E.F.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Anacleto, P.; et al. Interactive Effects of Laminaria digitata Supplementation and Heatwave Events on Farmed Gilthead Seabream Antioxidant Status, Digestive Activity, and Lipid Metabolism. Environments 2026, 13, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010025

Gomes RVC, Marmelo I, Chainho T, Pereira A, Bolotas D, Barata M, Pousão-Ferreira P, Vieira EF, Delerue-Matos C, Anacleto P, et al. Interactive Effects of Laminaria digitata Supplementation and Heatwave Events on Farmed Gilthead Seabream Antioxidant Status, Digestive Activity, and Lipid Metabolism. Environments. 2026; 13(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomes, Rita V. C., Isa Marmelo, Tomás Chainho, Alícia Pereira, Daniel Bolotas, Marisa Barata, Pedro Pousão-Ferreira, Elsa F. Vieira, Cristina Delerue-Matos, Patrícia Anacleto, and et al. 2026. "Interactive Effects of Laminaria digitata Supplementation and Heatwave Events on Farmed Gilthead Seabream Antioxidant Status, Digestive Activity, and Lipid Metabolism" Environments 13, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010025

APA StyleGomes, R. V. C., Marmelo, I., Chainho, T., Pereira, A., Bolotas, D., Barata, M., Pousão-Ferreira, P., Vieira, E. F., Delerue-Matos, C., Anacleto, P., Marques, A., Diniz, M. S., Bandarra, N. M., & Maulvault, A. L. (2026). Interactive Effects of Laminaria digitata Supplementation and Heatwave Events on Farmed Gilthead Seabream Antioxidant Status, Digestive Activity, and Lipid Metabolism. Environments, 13(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010025