Plastic Pollution and Framework Towards Sustainable Plastic Waste Management in Nigeria: Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

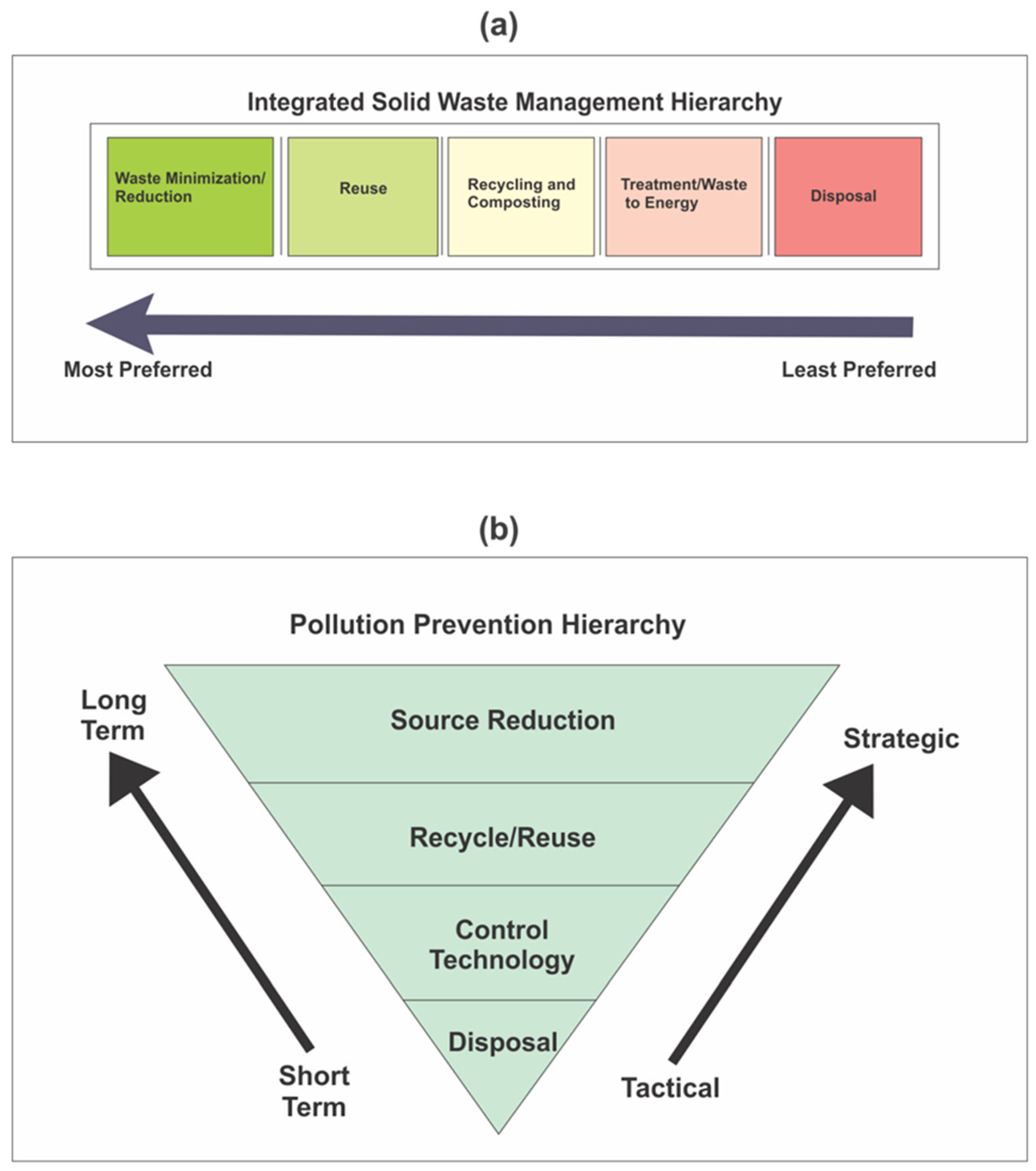

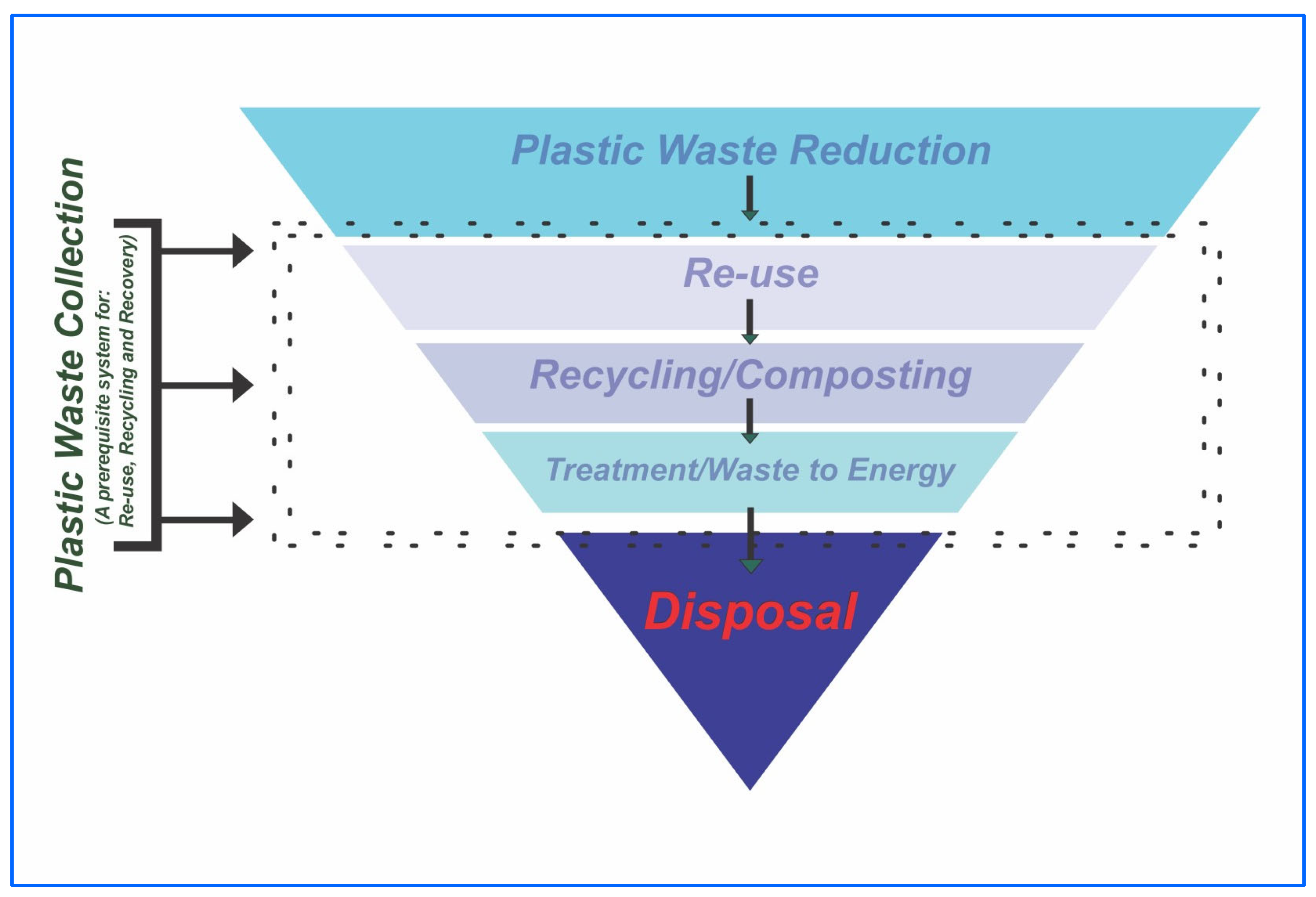

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Current State of Plastic Waste Management in Nigeria

2.2. Awareness on Environmental Impact of Plastic Pollution

2.3. Plastic Waste Collection

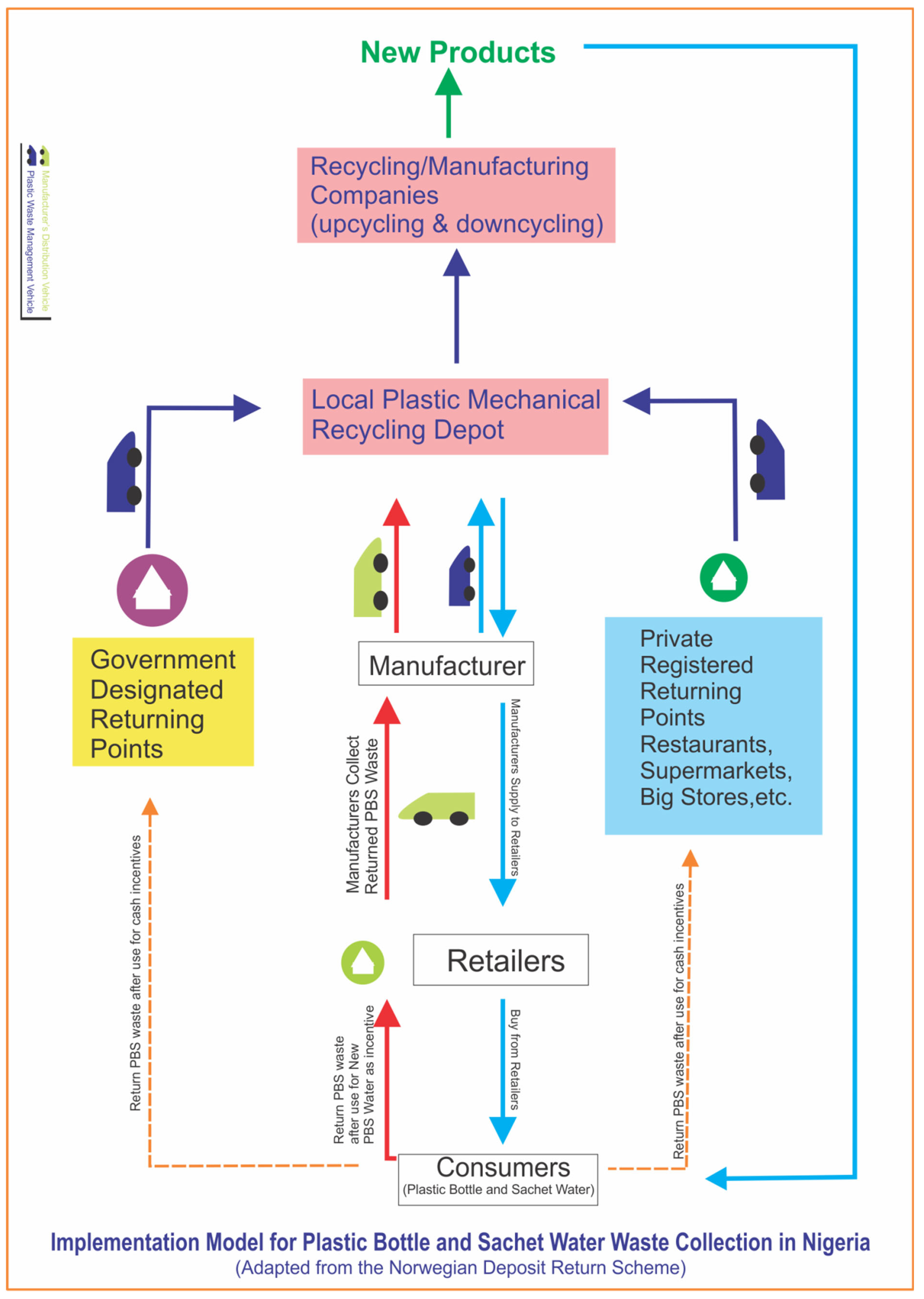

2.4. Norwegian Deposit Return Scheme (DRS)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Study Design

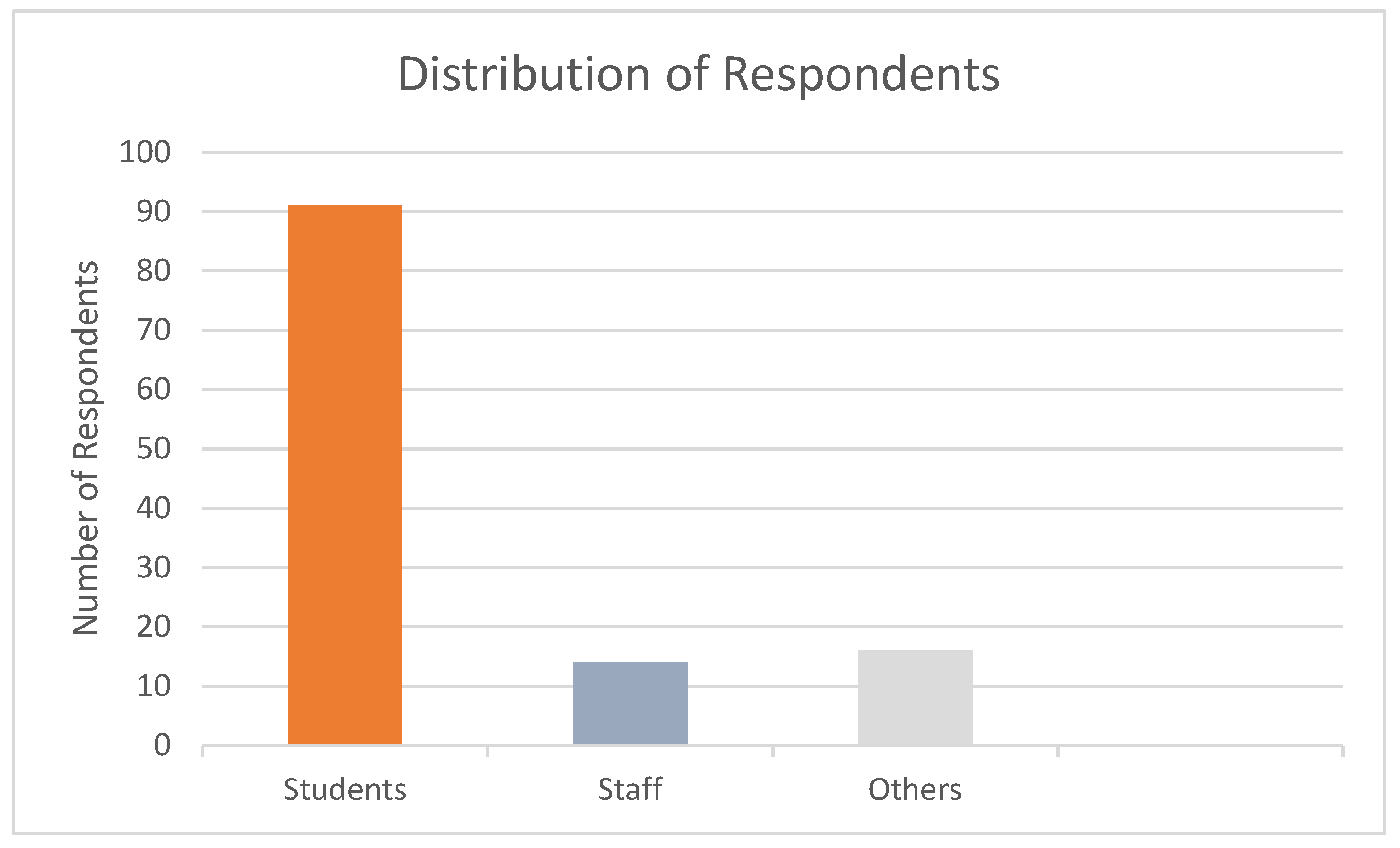

3.2.1. Sampling Technique and Study Participants

3.2.2. Survey Questions and Data Collection

4. Results and Discussion

Implications and Future Works

5. Conclusions

6. Limitation to This Study

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DRS | Deposit Return Scheme |

| ISWM | Integrated Solid Waste Management |

| PBSW | Plastic Bottle and Sachet Water |

| PPH | Plastic Pollution Hierarchy |

| PWM | Plastic Waste Management |

| SVSM | Sustainable Value Stream Mapping |

| VSM | Value Stream Mapping |

References

- Halden, R.U. Plastics and Health Risks. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2010, 31, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evode, N.; Qamar, S.A.; Bilal, M.; Barceló, D.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Plastic Waste and Its Management Strategies for Environmental Sustainability. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2021, 4, 100142. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666016421000645 (accessed on 2 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ezeudu, O.B.; Tenebe, I.T.; Ujah, C.O. Status of Production, Consumption, and End-of-Life Waste Management of Plastic and Plastic Products in Nigeria: Prospects for Circular Plastics Economy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Huang, W.; Chen, M.; Song, B.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y. (Micro)plastic crisis: Un-ignorable contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusa, R.; Joshua, W.K. Evaluating the potability and human health risk of sachet water in Wukari, Nigeria. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2022, 78, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoafia, N.; Joseph, A.; Edet, U.; Nwaokorie, F.; Henshaw, O.; Edet, B.; Asanga, E.; Mbim, E.; Chikwado, C.; Obeten, H. Deterioration of the quality of packaged potable water (bottled water) exposed to sunlight for a prolonged period: An implication for public health. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 175, 113728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahiabor, W.K.; Donkor, E.S. Microbial Safety of Sachet Water in Ghana: A Systematic Review. Environ. Health Insights 2025, 19, 11786302241307830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, L.; Dumbili, E. “Drinking and Dropping”: On Interacting with Plastic Pollution and Waste in South-Eastern Nigeria. Worldw. Waste J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2021, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galal, S. Population in Africa, by Country 2023; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1121246/population-in-africa-by-country/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Anabaraonye, B.; Olowoyeye, T.; Anukwonke, C.C. Mitigating the Negative Effects of Plastic Pollution for Sustainable Economic Growth in Nigeria. In Disaster Risk Reduction for Resilience; Springer EBooks: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uche, C.; Abubakar, S.A.; Nnamchi, S.N.; Ukagwu, K.J. Polyethylene terephthalate aggregates in structural lightweight concrete: A meta-analysis and review. Discov. Mater. 2023, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, O.; Orobosa Abraham, I.; Friday Osaru, O.-O. Externality Effects of Sachet and Plastic Bottled Water Consumption on the Environment: Evidence from Benin City and Okada in Nigeria. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Policy 2020, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egun, N.K.; Evbayiro, O.J. Beat the plastic: An approach to polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottle waste management in Nigeria. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2020, 2, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeudu, O.B.; Ezeudu, T.S. Implementation of Circular Economy Principles in Industrial Solid Waste Management: Case Studies from a Developing Economy (Nigeria). Recycling 2019, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, M.S.; Paramasivam, S.K.; Wanazusi, T.; Sundarrajan, K.J.; Erheyovwe, B.P.; Marshal Williams, A.M. Addressing Plastic Waste Challenges in Africa: The Potential of Pyrolysis for Waste-to-Energy Conversion. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M. Can Norway Help Us Solve the Plastic Crisis, One Bottle at a Time? The Guardian, 12 July 2018. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/jul/12/can-norway-help-us-solve-the-plastic-crisis-one-bottle-at-a-time (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Ibikunle, R.; Titiladunayo, I.; Dahunsi, S.; Akeju, E.; Osueke, C. Characterization and projection of dry season municipal solid waste for energy production in Ilorin metropolis, Nigeria. Waste Manag. Res. J. A Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2021, 39, 0734242X2098559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniran, A.E.; Nubi, A.T.; Adelopo, A.O. Solid waste generation and characterization in the University of Lagos for a sustainable waste management. Waste Manag. 2017, 67, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, L.A.; Afon, A.O. Seasonal quantification and characterization of solid waste generation in tertiary institution: A case study. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2022, 24, 1172–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, C.O.; Ozoegwu, C.G.; Ozor, P.A. Solid waste quantification and characterization in university of Nigeria, Nsukka campus, and recommendations for sustainable management. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.R. (Micro)plastics and the UN sustainable development goals. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. 2021, 30, 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.J.; Raps, H.; Cropper, M.; Bald, C.; Brunner, M.; Canonizado, E.M.; Charles, D.; Chiles, T.C.; Donohue, M.J.; Enck, J.; et al. The Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health. Ann. Glob. Health 2023, 89, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, V.; Chatterjee, S. Contribution of plastic and microplastic to global climate change and their conjoining impacts on the environment—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 875, 162627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassin, J.B.; Dijkstra, H. Plastic Venture Builder (PVB): An empirically derived assessment tool to support plastic waste management ventures in low- and middle-income countries. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 42, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluko, O.O.; Obafemi, T.H.; Obiajunwa, P.O.; Obiajunwa, C.J.; Obisanya, O.A.; Odanye, O.H.; Odeleye, A.O. Solid waste management and health hazards associated with residence around open dumpsites in heterogeneous urban settlements in Southwest Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 32, 1313–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferronato, N.; Maalouf, A.; Mertenat, A.; Saini, A.; Khanal, A.; Copertaro, B.; Yeo, D.; Jalalipour, H.; Raldúa Veuthey, J.; Ulloa-Murillo, L.M.; et al. A review of plastic waste circular actions in seven developing countries to achieve sustainable development goals. Waste Manag. Res. J. A Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2023, 42, 0734242X231188664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.; Lee, Z.; Shaleh, A.; Soo, H.S. The United Nations Environment Assembly resolution to end plastic pollution: Challenges to effective policy interventions. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Iacovidou, E. An overview of the challenges and trade-offs in closing the loop of post-consumer plastic waste (PCPW): Focus on recycling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 380, 120887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlert, S.; Bening, C.R. Why pledges alone will not get plastics recycled: Comparing recyclate production and anticipated demand. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNIDO. Nigeria Automates Plastic Waste Management with Locally Fabricated Reverse Vending Machines, Boosting Recycling Efforts in the Federal Capital Territory. 2024. Available online: https://www.unido.org/news/nigeria-automates-plastic-waste-management-locally-fabricated-reverse-vending-machines-boosting-recycling-efforts-federal-capital-territory (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Ford, H.V.; Jones, N.H.; Davies, A.J.; Godley, B.J.; Jambeck, J.R.; Napper, I.E.; Suckling, C.C.; Williams, G.J.; Woodall, L.C.; Koldewey, H.J. The fundamental links between climate change and marine plastic pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.J. Solving the plastic problem: From cradle to grave, to reincarnation. Sci. Prog. 2019, 102, 218–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejaswini, M.S.S.R.; Pathak, P.; Ramkrishna, S.; Ganesh, P.S. A comprehensive review on integrative approach for sustainable management of plastic waste and its associated externalities. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 825, 153973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letcher, T.M. Plastic Waste and Recycling: Environmental Impact, Societal Issues, Prevention, and Solutions; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/books/plastic-waste-and-recycling/letcher/978-0-12-817880-5 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Williams, A.T.; Rangel-Buitrago, N. The past, present, and future of plastic pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 176, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iroegbu, A.O.C.; Ray, S.S.; Mbarane, V.; Bordado, J.C.; Sardinha, J.P. Plastic pollution: A perspective on matters arising: Challenges and opportunities. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 19343–19355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakthipriya, N. Plastic waste management: A road map to achieve circular economy and recent innovations in pyrolysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 809, 151160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen-Taylor, K.O. Combining Extended Producer Responsibility (Epr) and Deposit Refund System (Drs) Policy for Higher Recovery and Recycling of Plastic Bottles and Sachet Water Waste: Application of Vending Machine and Designated Return Depot Centre in Lagos, Nigeria. Open J. Environ. Res. 2022, 3, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adibe, C.E.; Nwafor, N.; Ugwu, P.I.; Obuka, U.; Richards, N.U. Understanding the psychology and legal perspective of plastic dependency in Nigeria. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43, 2630–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhuoso, O.A. The Role of Educational Programs to enhance Stakeholder Participation for Sustainable Waste Management in Developing Countries: An Investigation into Public Secondary Schools in Nigeria. Int. J. Waste Resour. 2018, 1, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalu, M.T.B.; Cuthbert, R.N.; Muhali, H.; Chari, L.D.; Manyani, A.; Masunungure, C.; Dalu, T. Is Awareness on Plastic Pollution Being Raised in Schools? Understanding Perceptions of Primary and Secondary School Educators. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitou, A.; Naasan Aga-Spyridopoulou, R.; Mylona, Z.; Beck, R.; McLellan, F.; Addamo, A.M. Investigating the knowledge and attitude of the Greek public towards marine plastic pollution and the EU Single-Use Plastics Directive. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 166, 112182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowarah, K.; Duarah, H.; Devipriya, S.P. A preliminary survey to assess the awareness, attitudes/behaviours, and opinions pertaining to plastic and microplastic pollution among students in India. Mar. Policy 2022, 144, 105220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, C.; Esteban, M.Á.; Cuesta, A. Microplastics in Aquatic Environments and Their Toxicological Implications for Fish. In Toxicology—New Aspects to This Scientific Conundrum; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Plastics and microplastics factsheet. Heliyon 2015, 6, e04255. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/28420/Microplasen.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Lee, J.; Hong, S.; Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H.; Jang, Y.C.; Jang, M.; Heo, N.W.; Han, G.M.; Lee, M.J.; Kang, D.; et al. Relationships among the abundances of plastic debris in different size classes on beaches in South Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 77, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TOMBRA. Norway’s Deposit Return Scheme Is World’s Recycling Role Model. 2022. Available online: https://www.tomra.com/en/reverse-vending/media-center/featurearticles/norway-deposit-return-scheme (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Kehinde, A.; Awosusi, B.; Iyaniwura, S.; Ganiyu, Y. Plastic pollution in Nigeria: The need for legislation to tackle the menace. Kryt. Prawa Niezalez. Stud. Prawem 2023, 2023, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, W.; Mortazavi, R.; Cialani, C.; Nordström, J. How have waste management policies impacted the flow of municipal waste? An empirical analysis of 14 European countries. Waste Manag. 2023, 164, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.; Ahmed, W.; Najmi, A. Understanding consumers’ behaviour intentions towards dealing with the plastic waste: Perspective of a developing country. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 142, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, E. Leveraging public awareness and behavioural change for entrepreneurial waste management. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Nguyen, N.; Phung, P.; Yến-Khanh, N. Residents’ waste management practices in a developing country: A social practice theory analysis. Environ. Chall. 2023, 13, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawodu, A.; Oladejo, J.; Tsiga, Z.; Kanengoni, T.; Cheshmehzangi, A. Underutilization of waste as a resource: Bottom-up approach to waste management and its energy implications in Lagos, Nigeria. Intell. Build. Int. 2021, 14, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirasit, A. The Impact of Social Media Campaigns on Reducing Plastic Waste in Thailand’s Coastal Areas. Stud. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2024, 3, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S.; Nousheen, A.; Siddiquah, A. Effect of an environmental education course on prospective teachers’ pro-environmental behavior: A study in education for sustainable development perspective. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, R.; Leonard, S.A. Plastics and the Circular Economy; Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel (STAP) to the Global Environment Facility (GEF): Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tamburini, E.; Costa, S.; Summa, D.; Battistella, L.; Fano, E.A.; Castaldelli, G. Plastic (PET) vs bioplastic (PLA) or refillable aluminium bottles—What is the most sustainable choice for drinking water? A life cycle (LCA) analysis. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.Y.; Gholami, H.; Saman, M.Z.M.; Ngadiman, N.H.A.B.; Zakuan, N.; Mahmood, S.; Omain, S.Z. Sustainability-Oriented Application of Value Stream Mapping: A Review and Classification. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants | Students | Staff | Others | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Number | 91 | 14 | 16 | 121 |

| Percentage Distribution (%) | 75.2 | 11.6 | 13.2 | 100 |

| Stakeholder Groups. | Number of persons. | Assigned code Number. | ||

| Manufacturer | 2 | P1, P3 | ||

| Retailer | 2 | P2,P6 | ||

| Government Waste Management Authority | 1 | P4 | ||

| Private Waste Management Company | 1 | P5 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chilote, M.O.; Dhakal, H.N. Plastic Pollution and Framework Towards Sustainable Plastic Waste Management in Nigeria: Case Study. Environments 2025, 12, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12060209

Chilote MO, Dhakal HN. Plastic Pollution and Framework Towards Sustainable Plastic Waste Management in Nigeria: Case Study. Environments. 2025; 12(6):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12060209

Chicago/Turabian StyleChilote, Martha Ogechi, and Hom Nath Dhakal. 2025. "Plastic Pollution and Framework Towards Sustainable Plastic Waste Management in Nigeria: Case Study" Environments 12, no. 6: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12060209

APA StyleChilote, M. O., & Dhakal, H. N. (2025). Plastic Pollution and Framework Towards Sustainable Plastic Waste Management in Nigeria: Case Study. Environments, 12(6), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12060209