Impacts of PFAS Exposure on Neurodevelopment: A Comprehensive Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

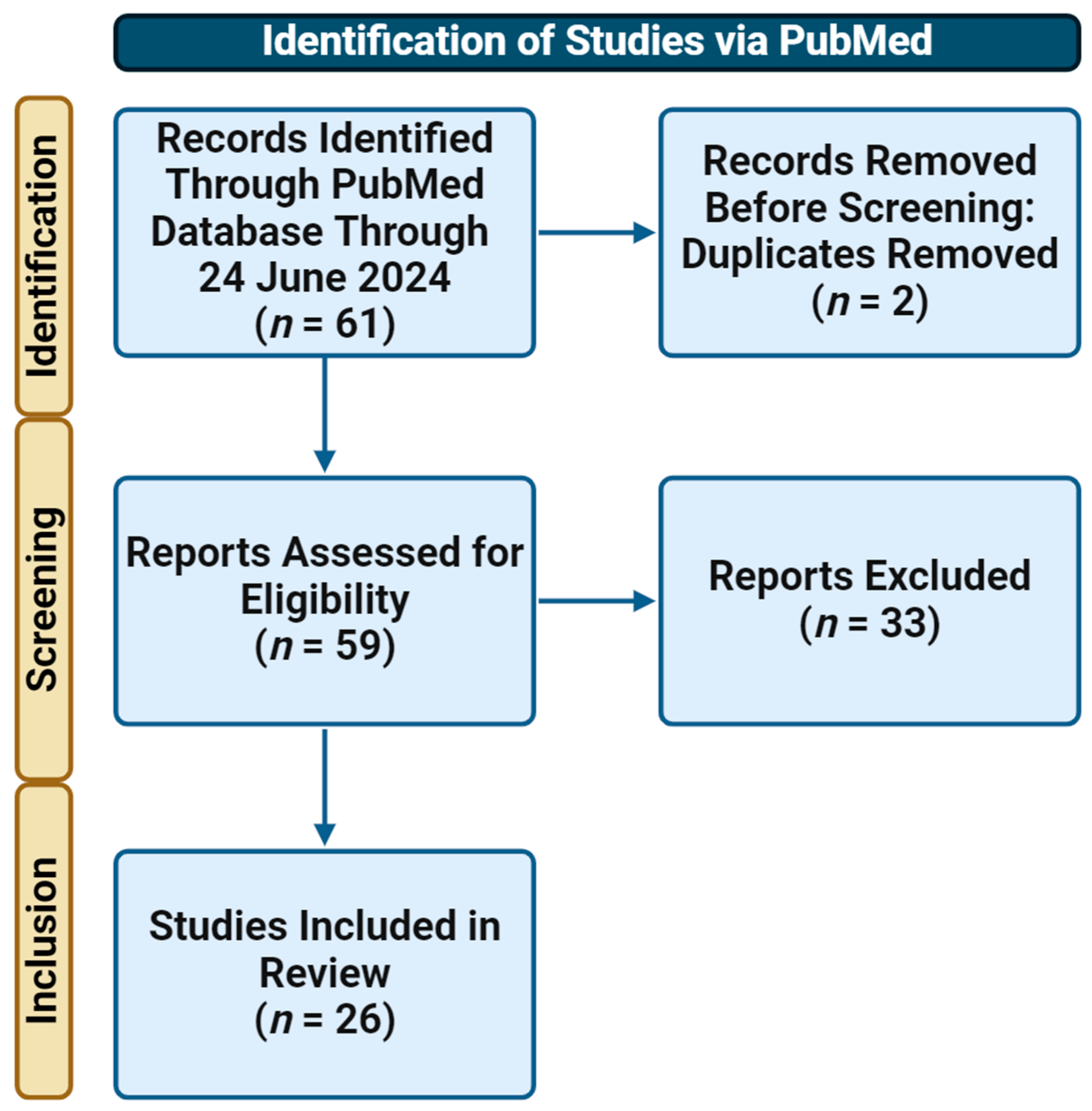

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sourcing

2.2. Exposure Assessment

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. The Intelligence Quotient (IQ)

3.2. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

3.3. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morris-Rosendahl, D.J.; Crocq, M.A. Neurodevelopmental disorders—The history and future of a diagnostic concept. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 22, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, W.D.; Kekatpure, M.V.; Kosofsky, B.E. Prenatal-onset neurodevelopmental disorders secondary to toxins, nutritional deficiencies, and maternal illness. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2013, 111, 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Ijomone, O.M.; Olung, N.F.; Akingbade, G.T.; Okoh, C.O.A.; Aschner, M. Environmental influence on neurodevelopmental disorders: Potential association of heavy metal exposure and autism. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 62, 126638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landrigan, P.J.; Lambertini, L.; Birnbaum, L.S. A research strategy to discover the environmental causes of autism and neurodevelopmental disabilities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, a258–a260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandjean, P.; Landrigan, P.J. Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals. Lancet 2006, 368, 2167–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, G.; Costa, L.G. Developmental neurotoxicity: Some old and new issues. ISRN Toxicol. 2012, 2012, 814795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makris, S.L.; Raffaele, K.; Allen, S.; Bowers, W.J.; Hass, U.; Alleva, E.; Calamandrei, G.; Sheets, L.; Amcoff, P.; Delrue, N.; et al. A retrospective performance assessment of the developmental neurotoxicity study in support of OECD test guideline 426. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panieri, E.; Baralic, K.; Djukic-Cosic, D.; Buha Djordjevic, A.; Saso, L. PFAS Molecules: A Major Concern for the Human Health and the Environment. Toxics 2022, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nisio, A.; Pannella, M.; Vogiatzis, S.; Sut, S.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Santa Rocca, M.; Antonini, A.; Porzionato, A.; De Caro, R.; Bortolozzi, M.; et al. Toni and C. Foresta. Impairment of human dopaminergic neurons at different developmental stages by perfluoro-octanoic acid (PFOA) and differential human brain areas accumulation of perfluoroalkyl chemicals. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderland, E.M.; Hu, X.C.; Dassuncao, C.; Tokranov, A.K.; Wagner, C.C.; Allen, J.G. A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratlen, M.J.; Perera, F.P.; Lederman, S.A.; Rauh, V.A.; Robinson, M.; Kannan, K.; Trasande, L.; Herbstman, J. The association between prenatal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances and childhood neurodevelopment. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263 Pt B, 114444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel, D.; Horowitz, L.; Wormuth, M.; Scheringer, M.; Cousins, I.T.; Hungerbühler, K. Estimating consumer exposure to PFOS and PFOA. Risk Anal. 2008, 28, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Death, C.; Bell, C.; Champness, D.; Milne, C.; Reichman, S.; Hagen, T. Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in livestock and game species: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 144795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, I.M.; Nadal, B.; van Bavel, G.; Lindstrom, J.L. Domingo. Levels of perfluorochemicals in water samples from Catalonia, Spain: Is drinking water a significant contribution to human exposure? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2008, 15, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzhaf, S.; Filipovic, M.; Lewis, J.; Sparrenbom, C.J.; Barthel, R. A review of contamination of surface-, ground-, and drinking water in Sweden by perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). Ambio 2017, 46, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo, J.L.; Nadal, M. Human exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) through drinking water: A review of the recent scientific literature. Environ. Res. 2019, 177, 108648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cousins, I.T.; DeWitt, J.C.; Glüge, J.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Ng, C.A.; Scheringer, M.; Wang, Z. The high persistence of PFAS is sufficient for their management as a chemical class. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2020, 22, 2307–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Pan, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Yao, B.; Dai, J. Exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in serum versus semen and their association with male reproductive hormones. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266 Pt 2, 115330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardener, H.; Sun, Q.; Grandjean, P. PFAS concentration during pregnancy in relation to cardiometabolic health and birth outcomes. Environ. Res. 2021, 192, 110287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.R.; McGovern, K.J.; Pajak, A.M.; Maglione, P.J.; Wolff, M.S. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances and indicators of immune function in children aged 12–19 y: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 79, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, E.; Stratakis, N.; Basagaña, X.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Casas, M.; Fossati, S.; Gražulevičienė, R.; Haug, L.S.; Heude, B.; Maitre, L.; et al. Prenatal and postnatal exposure to PFAS and cardiometabolic factors and inflammation status in children from six European cohorts. Environ. Int. 2021, 157, 106853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderete, T.L.; Jin, R.; Walker, D.I.; Valvi, D.; Chen, Z.; Jones, D.P.; Peng, C.; Gilliland, F.D.; Berhane, K.; Conti, D.V.; et al. Perfluoroalkyl substances, metabolomic profiling, and alterations in glucose homeostasis among overweight and obese Hispanic children: A proof-of-concept analysis. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, T.; Walker, D.I.; Thomas, D.C.; Qiu, C.; Chatzi, L.; Alderete, T.L.; Kim, J.S.; Conti, D.V.; Breton, C.V.; et al. Dysregulated lipid and fatty acid metabolism link perfluoroalkyl substances exposure and impaired glucose metabolism in young adults. Environ. Int. 2020, 145, 106091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Han, X.; Du, G.; Xia, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, C. Serum albumin mediates the effect of multiple per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances on serum lipid levels. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266 Pt 2, 115138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomberg, A.J.; Shih, Y.-H.; Messerlian, C.; Jørgensen, L.H.; Weihe, P.; Grandjean, P. Early-life associations between per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and serum lipids in a longitudinal birth cohort. Environ. Res. 2021, 200, 111400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A.F.; Xia, Q.; Peng, C.; Ng, J.C. Evaluation of the individual and combined toxicity of perfluoroalkyl substances to human liver cells using biomarkers of oxidative stress. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, P.M.; Salihovic, S.; van Bavel, B.; Lind, L. Circulating levels of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and carotid artery atherosclerosis. Environ. Res. 2017, 152, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorke-Monsen, A.-L.; Varsi, K.; Averina, M.; Brox, J.; Huber, S. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and mercury in never-pregnant women of fertile age: Association with fish consumption and unfavorable lipid profile. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2020, 3, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstens, K.E.; Freudenrich, T.; Wallace, K.; Choo, S.; Carpenter, A.; Smeltz, M.; Clifton, M.S.; Henderson, W.M.; Richard, A.M.; Patlewicz, G.; et al. Evaluation of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) In Vitro Toxicity Testing for Developmental Neurotoxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2023, 36, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Yang, Y.; He, D. Chronic exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonate induces behavior defects and neurotoxicity through oxidative damages, in vivo and in vitro. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 113453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Shin, H.-M.; Kannan, K.; Busgang, S.A.; Schmidt, R.J.; Schweitzer, J.B.; Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Bennett, D.H. Childhood exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and neurodevelopment in the CHARGE case-control study. Environ. Res. 2022, 215 Pt 2, 114322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Fu, Y.; Weng, X.; Zeng, Z.; Tan, Y.; Wu, X.; Zeng, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liang, H.; et al. The Association between Prenatal Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Exposure and Neurobehavioral Problems in Offspring: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, K.D.; Patisaul, H.B. Environmental Mechanisms of Neurodevelopmental Toxicity. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, L.G.; Cole, T.B.; Dao, K.; Chang, Y.-C.; Garrick, J.M. Developmental impact of air pollution on brain function. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 131, 104580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamm, M.P.; Cherry, N.M.; Chan, E.; Martin, J.W.; Burstyn, I. Maternal exposure to perfluorinated acids and fetal growth. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2010, 20, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi, J.T.; Avula, V.; Fry, R.C. Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Their Effects on the Placenta, Pregnancy, and Child Development: A Potential Mechanistic Role for Placental Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPARs). Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2020, 7, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erinc, A.; Davis, M.B.; Padmanabhan, V.; Langen, E.; Goodrich, J.M. Considering environmental exposures to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) as risk factors for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, B.E.; Fenton, S.E. Early life exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and latent health outcomes: A review including the placenta as a target tissue and possible driver of peri- and postnatal effects. Toxicology 2020, 443, 152565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yan, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Ren, S. Association of prenatal exposure to perfluorinated and polyfluoroalkyl substances with childhood neurodevelopment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 271, 115939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, J.; Bell, E.M. Determinants of maternal and neonatal PFAS concentrations: A review. Environ. Health 2023, 22, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Li, Q.-Q.; Chu, C.; Wang, S.-Z.; Tang, Y.-T.; Appleton, A.A.; Qiu, R.-L.; Yang, B.-Y.; Hu, L.-W.; Dong, G.-H.; et al. High trans-placental transfer of perfluoroalkyl substances alternatives in the matched maternal-cord blood serum: Evidence from a birth cohort study. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gützkow, K.B.; Haug, L.S.; Thomsen, C.; Sabaredzovic, A.; Becher, G.; Brunborg, G. Placental transfer of perfluorinated compounds is selective—A Norwegian Mother and Child sub-cohort study. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2012, 215, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, M.S.; Varde, M.; Newman, R.B. Environmental toxicants and placental function. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 85 Pt B, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, A.; Buchanan, S.; Liu, W. Exposure characteristics for congeners, isomers, and enantiomers of perfluoroalkyl substances in mothers and infants. Environ. Int. 2020, 144, 106012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantsæter, A.; Whitworth, K.; Ydersbond, T.; Haug, L.; Haugen, M.; Knutsen, H.; Thomsen, C.; Meltzer, H.; Becher, G.; Sabaredzovic, A.; et al. Determinants of plasma concentrations of perfluoroalkyl substances in pregnant Norwegian women. Environ. Int. 2013, 54, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, Z.; Goudarzi, H.; Oulhote, Y. Developmental Exposures to Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs): An Update of Associated Health Outcomes. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.-X.; Zuo, Q.-L.; Fu, X.-H.; Song, L.-L.; Cen, M.-Q.; Wu, J. Association between prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and neurodevelopment in children: Evidence based on birth cohort. Environ. Res. 2023, 236 Pt 2, 116812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullin, A.P.; Gokhale, A.; Moreno-De-Luca, A.; Sanyal, S.; Waddington, J.L.; Faundez, V. Neurodevelopmental disorders: Mechanisms and boundary definitions from genomes, interactomes and proteomes. Transl. Psychiatry 2013, 3, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.C.; Johns, L.E.; Meeker, J.D. Serum Biomarkers of Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Relation to Serum Testosterone and Measures of Thyroid Function among Adults and Adolescents from NHANES 2011–2012. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6098–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, B.F.; Ahmadireskety, A.; Aristizabal-Henao, J.J.; Bowden, J.A. A rapid and simple method to quantify per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in plasma and serum using 96-well plates. MethodsX 2020, 7, 101111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, V.; Abballe, A.; Dellatte, E.; Iacovella, N.; Ingelido, A.M.; De Felip, E. A Simple and Rapid Method for Quantitative HPLC MS/MS Determination of Selected Perfluorocarboxylic Acids and Perfluorosulfonates in Human Serum. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2020, 2020, 8878618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, B.C.; Bellinger, D.C.; Hopkins, M.R.; Coull, B.A.; Ettinger, A.S.; Jim, R.; Hatley, E.; Christiani, D.C.; Wright, R.O. Maternal and Cord Blood Manganese Concentrations and Early Childhood Neurodevelopment among Residents near a Mining-Impacted Superfund Site. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 067020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gansler, D.A.; Varvaris, M.; Schretlen, D.J. The use of neuropsychological tests to assess intelligence. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2017, 31, 1073–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smelror, R.E.; Ueland, T. Cognitive functioning in early-onset psychosis. In Adolescent Psychosis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 13, pp. 127–152. [Google Scholar]

- Chatham, C.H.; Taylor, K.I.; Charman, T.; D’Ardhuy, X.L.; Eule, E.; Fedele, A.; Hardan, A.Y.; Loth, E.; Murtagh, L.; Rubido, M.d.V.; et al. Adaptive behavior in autism: Minimal clinically important differences on the Vineland-II. Autism Res. 2018, 11, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, T.G.; King, T.Z.; Spencer, K.S. Mullen scales of early learning: The utility in assessing children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders, cerebral palsy, and epilepsy. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2013, 2, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujii, N.; Usami, M.; Naya, N.; Tsuji, T.; Mishima, H.; Horie, J.; Fujiwara, M.; Iida, J. Efficacy and Safety of Medication for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents with Common Comorbidities: A Systematic Review. Neurol. Ther. 2021, 10, 499–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biederman, J.; DiSalvo, M.; Vaudreuil, C.; Wozniak, J.; Uchida, M.; Woodworth, K.Y.; Green, A.; Farrell, A.; Faraone, S.V. The child behavior checklist can aid in characterizing suspected comorbid psychopathology in clinically referred youth with ADHD. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 138, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, C.V.; Till, C.; Green, R.; El-Sabbagh, J.; Arbuckle, T.E.; Hornung, R.; Lanphear, B.; Seguin, J.R.; Booij, L.; Fisher, M.; et al. Prenatal exposure to legacy PFAS and neurodevelopment in preschool-aged Canadian children: The MIREC cohort. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2023, 98, 107181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, I.H.; Bilenberg, N.; Möller, S.; Nielsen, F.; Grandjean, P.; Højsager, F.D.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Nielsen, C.; Jensen, T.K. Association Between Prenatal and Early Postnatal Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances and IQ Score in 7-Year-Old Children From the Odense Child Cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 192, 1522–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, A.M.; Webster, G.M.; Yolton, K.; Calafat, A.M.; Muckle, G.; Lanphear, B.P.; Chen, A. Prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and neurobehavior in US children through 8 years of age: The HOME study. Environ. Res. 2021, 195, 110825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Luo, F.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, L. Prenatal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances and child intelligence quotient: Evidence from the Shanghai birth cohort. Environ. Int. 2023, 174, 107912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, Z.; Ritz, B.; Bach, C.C.; Asarnow, R.F.; Bech, B.H.; Nohr, E.A.; Bossi, R.; Henriksen, T.B.; Bonefeld-Jørgensen, E.C.; Olsen, J. Prenatal Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances and IQ Scores at Age 5; a Study in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126, 067004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Rogan, W.J.; Chen, H.-Y.; Chen, P.-C.; Su, P.-H.; Chen, H.-Y.; Wang, S.-L. Prenatal exposure to perfluroalkyl substances and children’‘s’ IQ: The Taiwan maternal and infant cohort study. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2015, 218, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.H.; Oken, E.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Calafat, A.M.; Ye, X.; Bellinger, D.C.; Webster, T.F.; White, R.F.; Sagiv, S.K. Prenatal and childhood exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and child cognition. Environ. Int. 2018, 115, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skogheim, T.S.; Villanger, G.D.; Weyde, K.V.F.; Engel, S.M.; Surén, P.; Øie, M.G.; Skogan, A.H.; Biele, G.; Zeiner, P.; Øvergaard, K.R.; et al. Prenatal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances and associations with symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and cognitive functions in preschool children. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 223, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Dai, Y.; Ding, J.; Guo, J.; Qi, X.; Wu, C.; Zhou, Z. Prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, fetal thyroid function, and intelligence quotient at 7 years of age: Findings from the Sheyang Mini Birth Cohort Study. Environ. Int. 2024, 187, 108720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bünger, A.; Grieder, S.; Schweizer, F.; Grob, A. The comparability of intelligence test results: Group- and individual-level comparisons of seven intelligence tests. J. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 88, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, A.M.; Yolton, K.; Xie, C.; Dietrich, K.N.; Braun, J.M.; Webster, G.M.; Calafat, A.M.; Lanphear, B.P.; Chen, A. Prenatal and childhood exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and cognitive development in children at age 8 years. Environ. Res. 2019, 172, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forns, J.; Verner, M.-A.; Iszatt, N.; Nowack, N.; Bach, C.C.; Vrijheid, M.; Costa, O.; Andiarena, A.; Sovcikova, E.; Høyer, B.B.; et al. Early Life Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and ADHD: A Meta-Analysis of Nine European Population-Based Studies. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128, 57002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalsager, L.; Jensen, T.K.; Nielsen, F.; Grandjean, P.; Bilenberg, N.; Andersen, H.R. No association between maternal and child PFAS concentrations and repeated measures of ADHD symptoms at age 2(1/2) and 5 years in children from the Odense Child Cohort. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2021, 88, 107031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Kim, B.-N.; Lee, Y.A.; Shin, C.H.; Hong, Y.-C.; Døssing, L.D.; Hildebrandt, G.; Lim, Y.-H. Association between early-childhood exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances and ADHD symptoms: A prospective cohort study. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 879, 163081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, Z.; Ritz, B.; von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Bech, B.H.; Nohr, E.A.; Fei, C.; Bossi, R.; Henriksen, T.B.; Bonefeld-Jørgensen, E.C.; Olsen, J. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and childhood autism in association with prenatal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances: A nested case-control study in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skogheim, T.S.; Weyde, K.V.F.; Aase, H.; Engel, S.M.; Surén, P.; Øie, M.G.; Biele, G.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Haug, L.S.; et al. Prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and associations with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder in children. Environ. Res. 2021, 202, 111692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, S.; Yamazaki, K.; Suyama, S.; Ikeda-Araki, A.; Miyashita, C.; Bamai, Y.A.; Kobayashi, S.; Masuda, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Goudarzi, H.; et al. The association between prenatal perfluoroalkyl substance exposure and symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in 8-year-old children and the mediating role of thyroid hormones in the Hokkaido study. Environ. Int. 2022, 159, 107026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaak, I.; De Cock, M.; De Boer, M.; Lamoree, P.; Leonards, P.; Van de Bor, M. Prenatal Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Behavioral Development in Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2016, 13, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Bennett, D.H.; Calafat, A.M.; Tancredi, D.; Roa, D.L.; Schmidt, R.J.; Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Shin, H.-M. Prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in association with autism spectrum disorder in the MARBLES study. Environ. Int. 2021, 147, 106328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Oh, J.; Bennett, D.H.; Calafat, A.M.; Schmidt, R.J.; Shin, H.-M. Prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and child behavioral problems. Environ. Res. 2024, 251 Pt 1, 118511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.-M.; Bennett, D.H.; Calafat, A.M.; Tancredi, D.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Modeled prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in association with child autism spectrum disorder: A case-control study. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyall, K.; Yau, V.M.; Hansen, R.; Kharrazi, M.; Yoshida, C.K.; Calafat, A.M.; Windham, G.; Croen, L.A. Prenatal Maternal Serum Concentrations of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Association with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126, 017001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoadley, L.; Watters, M.; Rogers, R.; Werner, L.S.; Markiewicz, K.V.; Forrester, T.; McLanahan, E.D. Public health evaluation of PFAS exposures and breastfeeding: A systematic literature review. Toxicol. Sci. 2023, 194, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamsen, L.S.; Björvang, R.D.; Mucs, D.; Vinnars, M.-T.; Papadogiannakis, N.; Lindh, C.H.; Andersen, C.Y.; Damdimopoulou, P. Concentrations of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in human embryonic and fetal organs from first, second, and third trimester pregnancies. Environ. Int. 2019, 124, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanssen, L.; Dudarev, A.A.; Huber, S.; Odland, J.; Nieboer, E.; Sandanger, T.M. Partition of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in whole blood and plasma, assessed in maternal and umbilical cord samples from inhabitants of arctic Russia and Uzbekistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 447, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Yin, S.; Kelly, B.C.; Liu, W. Isomer-Specific Transplacental Transfer of Perfluoroalkyl Acids: Results from a Survey of Paired Maternal, Cord Sera, and Placentas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 5756–5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macheka-Tendenguwo, L.R.; Olowoyo, J.O.; Mugivhisa, L.L.; Abafe, O.A. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in human breast milk and current analytical methods. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 36064–36086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, A.; Avenbuan, O.N.; Romano, M.E.; Braun, J.M.; Tolstrup, J.S.; Vandenberg, L.N.; Fenton, S.E. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Breastfeeding as a Vulnerable Function: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies. Toxics 2023, 11, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, J.-M.; Chen, D.; Han, F.-J.; Guo, Y.; Zeng, L.; Lu, X.; Wang, F. A short review on human exposure to and tissue distribution of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragnarsdottir, O.; Abdallah, M.A.; Harrad, S. Dermal uptake: An important pathway of human exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances? Environ. Pollut. 2022, 307, 119478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, L.-Y.; Wen, T.-W.; Lien, G.-W.; Chien, K.-L.; Hsu, S.H.; Liao, C.-C.; Sung, F.-C.; Chen, P.-C.; Su, T.-C. Association between levels of serum perfluorooctane sulfate and carotid artery intima-media thickness in adolescents and young adults. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 3309–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, P.; Andersen, E.W.; Budtz-Jørgensen, E.; Nielsen, F.; Mølbak, K.; Weihe, P.; Heilmann, C. Serum vaccine antibody concentrations in children exposed to perfluorinated compounds. JAMA 2012, 307, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granum, B.; Haug, L.S.; Namork, E.; Stølevik, S.B.; Thomsen, C.; Aaberge, I.S.; van Loveren, H.; Løvik, M.; Nygaard, U.C. Pre-natal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances may be associated with altered vaccine antibody levels and immune-related health outcomes in early childhood. J. Immunotoxicol. 2013, 10, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.S.; Stanko, J.P.; Kato, K.; Calafat, A.M.; Hines, E.P.; Fenton, S.E. Gestational and chronic low-dose PFOA exposures and mammary gland growth and differentiation in three generations of CD-1 mice. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Tan, Y.S.; Harkema, J.R.; Haslam, S.Z. Differential effects of peripubertal exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid on mammary gland development in C57Bl/6 and Balb/c mouse strains. Reprod. Toxicol. 2009, 27, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Espinosa, M.-J.; Mondal, D.; Armstrong, B.; Bloom, M.S.; Fletcher, T. Thyroid function and perfluoroalkyl acids in children living near a chemical plant. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1036–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-S.; Lin, C.-C.; Chen, M.-H.; Hsieh, W.-S.; Chen, P.-C. Perfluoroalkyl substances and thyroid hormones in cord blood. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 222, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Wen, L.-L.; Lin, L.-Y.; Wen, T.-W.; Lien, G.-W.; Hsu, S.H.; Chien, K.-L.; Liao, C.-C.; Sung, F.-C.; Chen, P.-C.; et al. The associations between serum perfluorinated chemicals and thyroid function in adolescents and young adults. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 244–245, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataria, A.; Trachtman, H.; Malaga-Dieguez, L.; Trasande, L. Association between perfluoroalkyl acids and kidney function in a cross-sectional study of adolescents. Environ. Health 2015, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.-D.; Qian, Z.; Vaughn, M.G.; Huang, J.; Ward, P.; Zeng, X.-W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, P.; Li, M.; et al. Positive associations of serum perfluoroalkyl substances with uric acid and hyperuricemia in children from Taiwan. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 212, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, C.; McLaughlin, J.K.; Lipworth, L.; Olsen, J. Prenatal exposure to perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and maternally reported developmental milestones in infancy. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 1391–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, H.; Nakajima, S.; Ikeno, T.; Sasaki, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Miyashita, C.; Ito, S.; Araki, A.; Nakazawa, H.; Kishi, R. Prenatal exposure to perfluorinated chemicals and neurodevelopment in early infancy: The Hokkaido Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 541, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.R.; Savitz, D.A.; Bellinger, D.C. Perfluorooctanoate and neuropsychological outcomes in children. Epidemiology 2013, 24, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenti, I.; Rabaneda, L.G.; Schoen, H.; Novarino, G. Neurodevelopmental Disorders: From Genetics to Functional Pathways. Trends Neurosci. 2020, 43, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antolini, G.; Colizzi, M. Where Do Neurodevelopmental Disorders Go? Casting the Eye Away from Childhood towards Adulthood. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, M.; Chavarro, J.E.; Hamra, G.B.; Hart, J.E.; Tabb, L.P.; Weisskopf, M.G.; Volk, H.E.; Lyall, K. Prenatal Diet as a Modifier of Environmental Risk Factors for Autism and Related Neurodevelopmental Outcomes. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2022, 9, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabhukumr, A.; Malhi, P.; Ravindra, K.; Lakshmi, P. Exposure to household air pollution during first 3 years of life and IQ level among 6–8-year-old children in India- A cross-sectional study. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 709, 135110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.B. Psychometrics, intelligence, and public perception. Intelligence 1997, 24, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqubal, A.; Ahmed, M.; Ahmad, S.; Sahoo, C.R.; Iqubal, M.K.; Haque, S.E. Environmental neurotoxic pollutants: Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 41175–41198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapar, A.; Cooper, M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 2016, 387, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsoklenis, A.; Honkasilta, J. ADHD in the DSM-5-TR: What has changed and what has not. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1064141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Sun, M. Autism Spectrum Disorder: Neurodevelopmental Risk Factors, Biological Mechanism, and Precision Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, T.; King, B.H. Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review. JAMA 2023, 329, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, T.E.; Mazefsky, C.A.; Vasa, R.A.; Lerner, M.D. Co-occurring psychiatric conditions in autism spectrum disorder. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2018, 30, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First Author/Year/Country | Design | Sample Size | Age of Children | PFAS | Sample/ Measuring Method | Exposure Measure | Test Type and Indicator | Adjustment of Covariates | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carly V Goodman/2023/Canada [59] | Cohort Study | n = 522 | Between 3 and 4 | PFOA, PFOS, and PFHxS | Plasma/ UHPLC–MS/MS | PFOA: 1.68 (1.10–2.50), PFOS: 4.97 (3.20–6.20), PFHxS: 1.09 (0.67–1.60) (µg/L) | Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Third Edition (WPPSI-III), composite full-scale IQ (FSIQ), performance IQ (PIQ), and verbal IQ (VIQ) scores | Gestational week of blood sampling, maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, country of birth (Canadian born, foreign born), maternal level of education (trade school diploma or lower, bachelor’s degree or higher), parity (0, 1, 2+), maternal smoking during pregnancy (current smoker, former smoker, never smoked), study site, and the Home Observation Measurement of the Environment (HOME) score, a continuous measure of the quality of the child’s home environment | Each doubling of PFHxS levels corresponded to a reduction of 2.0 points (95% CI: −3.6, −0.5) in FSIQ and 2.9 points (95% CI: −4.7, −1.1) in PIQ in males. However, in females, PFHxS showed no association with FSIQ or PIQ. PFOA and PFOS were also linked to lower PIQ scores in males (PFOA: B = −2.8, 95% CI: −4.9, −0.7; PFOS: B = −2.6, 95% CI: −4.8, −0.5), while in females, they were slightly positively associated with PIQ, but not FSIQ |

| Iben Have Beck/2023/Denmark [60] | Cohort Study | n = 967 | 7 years old | PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, PFNA, and PFDA | Serum/ LC–MS | PFOS: 4.61 (3.08–7.08), PFOA: 2.48 (1.58–3.49), PFHxS: 0.33 (0.21–0.50), PFNA: 0.57 (0.40–0.78), PFDA: 0.18 (0.13–0.24) (ng/mL) | Abbreviated version of the Danish WISC-V, Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ) score, and Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) score | Maternal educational level, BMI, and sex | PFOS and PFNA exposure and FSIQ remained significant, with β coefficients of −1.7 (95% CI: −3.0, −0.3) and −1.7 (95% CI: −3.0, −0.4) |

| Ann M Vuong/2019/United States [69] | Cohort Study | n = 221 | 3 and 8 years old | PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, and PFNA | Serum/ HPLC–MS/MS | PFOA: 2.4, PFOA: 3.9, PFHxS: 1.4, PFNA: 0.8 (ng/mL) | Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) and Full Scale IQ (FSIQ) | Maternal sociodemographic, behavioral factors, and biological measurements of environmental chemical | Findings do not support that PFAS are adversely associated with cognitive function |

| Hui Wang/2023/China [62] | Cohort Study | n = 2031 | 4 years old | PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFUA, PFDA, PFHxS, PFBS, PFDoA, PFHpA, and PFOSA | Plasma/ HPLC–MS/MS | PFOA: 13.12 (9.36–15.50), PFOS: 11.3 (6.66–13.68), PFNA: 2.05 (1.27–2.49), PFDA: 2.16 (1.18–2.67), PFHxS: 0.62 (0.42–0.69) (ng/mL) | Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scales of Intelligence-Fourth Edition (WPPSI-IV) | Maternal age at delivery, maternal educational level, maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index, parity, maternal folic acid intake during pregnancy, maternal place of birth, maternal active/passive smoking status during pregnancy, maternal freshwater fish intake during pregnancy, and self-reported economic status | No significant associations between ln-transformed nine individual PFAS and child full scale IQ (FSIQ) or subscale IQ after adjusting for potential confounders |

| Zeyan Liew/2018/Norway [63] | Cohort Study | n = 1592 | 5 years old | PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, PFNA, PFHpS, PFDA, and PFOSA | Plasma/ LC–MS/MS | PFOS: 28.10 (21.60–35.80), PFOA: 4.28 (3.51–5.49), PFHxS: 1.07 (0.76–1.38), PFNA: 0.46 (0.36–0.57), PFHpS: 0.37 (0.27–0.49), PFDA: 0.17 (0.14–0.22), PFOSA: 2.32 (1.38–4.16) (ng/mL) | Wechsler Primary and Preschool Scales of Intelligence–Revised (WPPSI-R) | Maternal age at delivery, parity, maternal IQ, socioeconomic status, maternal smoking during pregnancy, maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy, maternal prepregnancy BMI, child’s sex | There is no reliable evidence establishing a connection between prenatal exposure to PFAS and IQ scores in children at the age of five |

| Yan Wang/2015/United States [64] | Cohort Study | n = 120 | 5 years old | PFHxS, PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFDeA, PFUnDA, PFDoDA, PFHpA, and PFHxA | Serum/ HPLC–MS/MS | PFHxS: 0.45 (0.35–0.57), PFOA: 2.00 (1.72–2.33), PFOS: 11.5 (10.2–13.07), PFNA: 1.33 (1.12–1.59), PFDeA: 0.39 (0.34–0.44), PFUnDA: 3.05 (2.37–3.94), PFDoDA: 0.29 (0.25–0.34) (ng/mL) | Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ), verbal IQ (VIQ) and performance IQ (PIQ) | Maternal age, maternal education, previous live births, family income, and maternal fish consumption during pregnancy | Exposure to two types of long-chain PFAS during pregnancy has been linked to lower IQ scores in children |

| Maria H Harris/2018/United States [65] | Cohort Study | n = 1226 | 3 years old | PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, MeFOSAA, and PFDeA | Plasma/ HPLC–MS/MS | PFOA: 4.4 (3.1–6.0), PFOS: 6.2 (4.2–9.7), PFHxS: 1.9 (1.2–3.4), PFNA: 1.5 (1.1–2.3), MeFOSAA: 0.3 (<LOD −0.6), PFDeA: 0.3 (0.2–0.5) (ng/mL) | Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT-III), Wide Range Assessment of Visual Motor Abilities (WRAVMA), Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (KBIT-2), and Visual Memory Index of the Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning (WRAML2) | Child sex, age at cognitive testing, maternal race/ethnicity, age, maternal and paternal education, socioeconomic status and maternal intelligence scores | Prenatal PFAS were associated with both better and worse cognitive scores |

| Miranda J. Spratlen/2020/United States [11] | Cohort Study | n = 110 | Children ages 3–7 years | PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, PFNA, PFDS, PFBS, PFOSA, PFHxA, PFHpA, PFDA, PFUnDA, and PFDoDA | Plasma/ HPLC–MS/MS | PFOS: 6.27 (1.05, 33.7), PFOA: 2.37 (0.18, 8.14), PFNA: 0.45 (<LOQ, 10.3), PFHxS: 0.69 (<LOQ, 15.8), PFDS: 0.13 (<LOQ, 0.64) (ng/mL) | Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID-II), Mental Development Index (MDI), Psychomotor Development Index (PDI), and Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI) | Maternal age; material hardship during pregnancy; pre-pregnancy BMI; maternal IQ; maternal race; maternal education; home smoking exposure; marital status; parity; child’s gestational age at birth; exact child age on test date; child’s sex; maternal demoralization score; and child breastfeeding history | Findings on prenatal PFAS exposure and child neurodevelopment are inconsistent |

| Thea S. Skogheim/2020/Norway [66] | Longitudinal Prospective Study | n = 944 | 3.5 years old | PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFUnDA, PFHxS, PFHpS, and PFOS | Plasma/ LC–MS/MS | PFOA: 2.50 (1.77–3.21), PFNA: 0.41 (0.29–0.53), PFDA: 0.15 (0.10–0.23), PFUnDA: 0.22 (0.14–0.32), PFHxS: 0.65 (0.46–0.88), PFHpS: 0.15 (0.10–0.20), PFOS: 11.51 (8.77–14.84) (ng/mL) | The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment interview, Child Development Inventory and Stanford–Binet (5th revision) | Maternal age, maternal education, maternal fish intake, parity, maternal ADHD symptoms, child sex, premature birth, birth weight, maternal BMI, maternal smoking, maternal alcohol consumption, maternal anxiety/depression and maternal iodine intake | No consistent evidence to conclude that prenatal exposure to PFAS are associated with cognitive dysfunctions in preschool children aged three and a half years |

| Boya Zhang/2024/China [67] | Cohort Study | n = 327 | 7 years old | PFHpA, PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFUnDA, PFDoDA, PFBS, PFHxS, PFHpS, PFOS, PFDS, and PFOSA | Serum/ UHPLC–MS/MS | PFHpA: 0.27 (0.23–0.30), PFOA: 3.51 (3.29–3.75), PFNA: 0.32 (0.28–0.36), PFDA: 0.86 (0.76–0.96), PFUnDA: 0.61 (0.57–0.65), PFDoDA: 0.13 (0.12–0.14), PFBS: 0.08 (0.07–0.09), PFHxS: 0.09 (0.08–0.10), PFHpS: 0.06 (0.05–0.07), PFOS: 2.10 (1.98–2.22) (ng/mL) | Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Chinese Revised (WISC-CR) | Maternal age at delivery, parity, maternal educational level, child’s sex, annual household income, pet ownership, changes in marital status, pre-pregnancy BMI | Increased prenatal exposure to PFAS negatively affected the IQ of school-aged children |

| First Author/Year/Country | Design | Sample Size | Age of Children | PFAS | Sample/Measuring Method | Exposure Measure | Test Type and Indicator | Adjustment of Covariates | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joan Forns/2020/Norway [70] | Cross-Sectional Study | n = 518 | 3, 6, 12, and 24 months of age | PFOS and PFOA | Serum/ HPLC–MS/MS | PFOS: 20.19 (4.1–87.3), PFOA: 1.83 (0.5–5.1) (ng/mL) | Attention Syndrome Scale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL-ADHD), Hyperactivity/Inattention Problems subscale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-Hyperactivity/Inattention), and ADHD Criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (ADHD-DSM-IV) | Maternal prepregnancy body mass index, maternal age at delivery, maternal education, maternal smoking during pregnancy, maternal parity, duration of total breastfeeding, and child sex | Exposure to PFOS or PFOA early in life was not linked to ADHD during childhood, with odds ratios (ORs) varying between 0.96 (95% CI: 0.87, 1.06) and 1.02 (95% CI: 0.93, 1.11). Analysis using stratified models indicates that the impact of PFAS may vary based on the child’s sex and the mother’s level of education |

| Louise Dalsager/2021/Denmark [71] | Cohort Study | n = 1138 | 2.5–5 years old | PFHxS, PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, and PFDA | Serum/ LC–MS/MS | PFOS: 4.65 (11.22), PFOA: 2.43 (6.40), PFHxS: 0.32 (0.81), PFNA: 0.58 (1.24), PFDA: 0.18 (0.37), Median (95th percentile) (ng/mL) | Child Behavior Checklist 1.5–5 | Parity, maternal educational level, parental psychiatric diagnosis, child sex | No correlation has been found between PFAS levels in mothers or children and symptoms of ADHD |

| Johanna Inhyang Kim/2023/South Korea [72] | Prospective Cohort Study | n = 521 | 2, 4, and 8 years old | PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFUnDA, PFHxS, and PFOS | Serum/ HPLC–MS/MS | PFOA: 3.61 (1.91–6.72), PFNA: 0.99 (0.45–2.96), PFDA: 0.34 (0.12–0.94), PFUnDA: 0.45 (0.17–0.94), PFHxS: 1.01 (0.54–1.95), PFOS: 3.94 (1.80–7.47) (ng/mL | ADHD Rating Scale IV (ARS) | Mother’s age during pregnancy, mother’s educational attainment, father’s educational background, socioeconomic conditions, maternal smoking during pregnancy, use of assisted reproductive technologies, maternal stress levels during pregnancy | PFAS exposure at age 2 was associated with ADHD development at age 8 |

| Ann M Vuong/2021/United States [61] | Cohort Study | n = 240 | 5 and 8 years old | PFOA, PFHxS, PDNA, and PFOS | Serum/ HPLC–MS/MS | PFOA: 5.3 (1.7), PFOS: 12.8 (1.7), PFHxS: 1.5 (0.8), PFNA: 0.90 (1.5), mean (SD) (ng/mL) | The Behavioral Assessment System for Children-2 (BASC-2) and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children–Young Child (DISC-YC) were used to evaluate ADHD symptoms and diagnostic criteria | Maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, family income, ln-maternal serum cotinine (ng/mL), maternal depression, marital status, maternal IQ, parity, and child sex | PFOS and PFNA were consistently linked to hyperactive-impulsive ADHD traits across two validated assessment tools |

| Thea S. Skogheim/2021/Norway [74] | Cohort Study | n = 821 | 3 years old | PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFUnDA, PFHxS, PFHpS, and PFOS | Plasma/ LC–MS/MS | PFOA: 2.46 (3.46–2.86), PFNA: 0.42 (0.20–0.49), PFDA: 0.19 (0.15–0.23) (ng/mL) | Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS screener) | Child sex, birth weight, and small for gestational age (SGA); maternal age at delivery, education, parity, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), self-reported smoking and alcohol intake during pregnancy, as well as FFQ-based estimates of seafood (g/day), and dietary iodine intake (μg/day) | Several PFAS (PFUnDA, PFDA, and PFOS) were inversely associated with odds of ADHD and/or ASD |

| Sachiko Itoh/2022/Japan [75] | Prospective Cohort Study | n = 770 | 8 years old | PFHxS, PFOS, PFHxA, PFHpA, PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFUnDA, PFDoDA, PFTrDA, and PFTeDA | Plasma/ UHPLC–MS/MS | PFHxS: 0.32 (0.22–0.41), PFOS: 6.66 (4.92–8.31), PFOA: 2.48 (1.50–3.00), PFNA: 1.16 (0.79–1.38), PFDA: 0.53 (0.34–0.62), PFUnDA: 1.37 (0.73–1.73), PFDoDA: 0.18 (0.12–0.23), PFTrDA: 0.35 (0.24–0.44) (ng/mL) | ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS) | Age of the mother at delivery, number of previous pregnancies, level of education, body mass index before pregnancy, alcohol consumption during pregnancy, smoking habits during pregnancy, and the sex of the child | Higher the maternal PFAS levels, lower the risk of ADHD symptoms at 8 y of age |

| Ilona Quaak/2016/The Netherlands [76] | Cohort Study | n = 76 | 18 months | PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFHpS, PFNA, PFDA, and PFUnDA | Plasma/ LC–MS/MS | PFOA: 905.6 (437.1), PFOS: 1583.6 (648.3), PFHxS: 140.0 (69.2), PFHpS: 35.6 (21.3), PFNA: 140.0 (61.8), PFDA: 52.2 (20.9), PFUnDA: 32.05 (11.9), Mean (SD) (ng/L) | Child Behavior Checklist 1.5–5 (CBCL) | Family history, educational level, smoking, alcohol use and illicit drug use during pregnancy | Prenatal exposure to PFAS showed no significant associations with ADHD scores |

| Thea S. Skogheim/2020/Norway [66] | Cohort Study | n = 944 | 3.5 years old | PFHpS, PFOS, PFHxS, PFOA, PFDA, PFUnDA, and PFNA | Plasma/ LC–MS/MS | PFOA: 2.61 (1.77–3.21), PFNA: 0.45 (0.29–0.53), PFDA: 0.19 (0.10–0.23), PFUnDA: 0.25 (0.05–0.32), PFHxS: 0.79 (0.46–0.88), PFHpS: 0.16 (0.10–0.20), PFOS: 12.32 (8.77–14.84), (ng/mL) | The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment interview, Child Development Inventory and Stanford–Binet (5th revision) | Maternal age, maternal education, maternal fish intake, parity, maternal ADHD symptoms, child sex, premature birth, birth weight, maternal BMI, maternal smoking, maternal alcohol consumption, maternal anxiety/depression and maternal iodine intake | Consistent evidence was not found to link prenatal PFAS exposure with ADHD symptoms or cognitive impairments in preschool children around three and a half years old |

| Zeyan Liew/2015/United States [73] | Cohort Study | n = 220 | Average 10.7 years old | PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, PFHpS, PFNA, and PFDA | Plasma/ LC–MS/MS | PFOS: 26.80 (19.20, 35.00), PFOA: 4.06 (3.08, 5.50), PFHxS: 0.84 (0.61, 1.15), PFHpS: 0.30 (0.20, 0.40), PFNA: 0.42 (0.34, 0.52), PFDA: 0.15 (0.11, 0.20), (ng/mL) | ICD-10 codes F90.0 | Maternal age at delivery, socioeconomic status, maternal smoking, alcohol drinking during pregnancy, mother’s self-reported psychiatric illnesses, child’s birth year, child’s sex | Evidence does not consistently support a link between prenatal PFAS exposure and an increased risk of ADHD |

| First Author/Year/Country | Design | Sample Size | Age of Children | PFAS | Sample/Measuring Method | Exposure Measure | Test Type and Indicator | Adjustment of Covariates | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thea S. Skogheim/2021/Norway [74] | Cohort Study | n = 400 | 3 years old | PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFUnDA, PFHxS, PFHpS, and PFOS | Plasma/ LC–MS/MS | PFOA: 2.46 (3.46–2.86), PFNA: 0.42 (0.20–0.49), PFDA: 0.19 (0.15–0.23) (ng/mL) | Diagnoses of “pervasive developmental disorders” were identified using ICD-10 codes F84.0, F84.1, F84.5, F84.8, or F84.9 | Child’s sex, birth weight, and status as small for gestational age (SGA); maternal age at delivery, education level, number of previous births, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), self-reported smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy, as well as estimates of seafood intake (g/day) and dietary iodine intake (μg/day) based on a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). | An increased risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) was observed in the second quartile of PFOA exposure [OR = 1.71 (95% CI: 1.20, 2.45)]. Conversely, PFUnDA, PFDA, and PFOS were associated with a reduced likelihood of ADHD, and the overall PFAS mixture showed a decreased risk of ASD [OR = 0.76 (95% CI: 0.64, 0.90)]. |

| Jiwon Oh/2022/United States [31] | Case–control Study | n = 551 | 2–5 years old | PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, PFDA, PFPeA, PFUnDA, PFBS, PFHxA, MeFOSAA, and EtFOSAA | Serum/ HPLC–MS/MS | PFOA: 2.20 (0.91, 6.30), PFOS: 2.01 (0.81, 8.01), PFHxS: 0.59 (0.20, 3.05), PFNA: 0.71 (0.26, 2.49), PFDA: 0.14 (0.06, 0.49), PFPeA: 0.51 (0.20, 1.33), PFHpA: 0.23 (0.03, 1.00), PFUnDA: 0.03 (<LOD, 0.13), PFBS: <LOD (<LOD, 0.10), PFHxA: <LOD (<LOD, 0.43), MeFOSAA: 0.10 (<LOD, 1.56), EtFOSAA: <LOD (<LOD, 0.06) (ng/mL) | Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS) are combined to generate an Early Learning Composite (Composite) score | Child’s sex, age at sampling, recruitment regional center; sampling year; gestational age at delivery, maternal factors, parity, breastfeeding duration, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. | PFOA was linked to higher odds of ASD, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.99 per log ng/mL increase (95% CI: 1.20, 3.29). PFHpA also showed increased odds of ASD with an OR of 1.61 (95% CI: 1.21, 2.13). Conversely, perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUnDA) was associated with lower odds of ASD, showing an OR of 0.43 (95% CI: 0.26, 0.69). Additionally, mixtures of PFAS were associated with increased odds of ASD, with an average OR of 1.57 and a range from the 5th to 95th percentile of 1.16 to 2.13. |

| Jiwon Oh/2021/United States [77] | Cohort Study | n = 57 | 3 years old | PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, PFDA, PFUnDA, PFDoDA, MeFOSAA, and EtFOSAA | Serum/ Reverse-Phase LC–MS/MS | PFOA: 0.9 (0.3–2.3), PFOS: 3.0 (1.1–6.8), PFHxS 0.4 (0.2–1.6), PFNA 0.5 (0.2–1.0), PFDA 0.1 (<LOD −0.4), PFUnDA 0.1 (<LOD −0.3), PFDoDA: <LOD (<LOD −0.1), MeFOSAA: 0.1 (<LOD −0.8), EtFOSAA <LOD (<LOD-<LOD) (ng/mL) | Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) | Child’s sex, birth year, maternal vitamin intake in the first month of pregnancy, maternal education, and homeownership. | PFOA and PFNA were positively associated with ASD risk, with relative risks (RR) of 1.20 (95% CI: 0.90, 1.61) and 1.24 (95% CI: 0.91, 1.69), respectively, for each 2-fold increase in concentration. In contrast, PFHxS was negatively associated with ASD risk, showing an RR of 0.88 (95% CI: 0.77, 1.01). |

| Jeong Weon Choi/2024/United States [78] | Cohort Study | n = 280 | 3 years old | PFHxS, PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, and PFDA | Serum/ Reverse-Phase LC–MS/MS | PFHxS: 0.45 (0.2–1.60), PFOS: 2.93 (1.10–7.00), PFOA: 0.87 (0.35–2.10), PFNA: 0.48 (0.20–1.00), PFDA 0.14 (<LOD −0.40) (ng/mL) | Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule and Mullen Scales of Early Mullen Scales of Early Learning | Child sex, child age at assessment, year of birth, gestational age at delivery, maternal age at delivery, parity, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal race/ethnicity, maternal education, breastfeeding duration, homeownership, maternal smoking status during pregnancy, and child ASD outcome group. | PFOS, PFNA, and PFDA were associated with several behavioral problems among children diagnosed with ASD. |

| Hyeong-Moo Shin/2020/United States [79] | Case–control Study | n = 239 | 2–5 years old | PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, and PFNA | Plasma/ Reverse-Phase HPLC–MS/MS | PFOA: 1.07 (0.37–3.40), PFOS: 3.10 (1.08–10.03), PFHxS: 0.50 (0.20–1.63), PFNA: 0.50 (<LOD −1.23) (ng/mL) | Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL), the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS), Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedules-Generic (ADOS-G) | Age and sex of the child at the time of assessment, year of birth, regional center of recruitment, number of previous pregnancies, gestational age at birth, maternal race/ethnicity, place of maternal birth, mother’s age at delivery, maternal BMI before pregnancy, vitamin intake around conception, duration of breastfeeding. | Increases in PFHxS and PFOS levels were tentatively connected to a higher risk of ASD diagnosis in children. For each nanogram per milliliter increase, PFHxS had an odds ratio of 1.46 (95% CI: 0.98, 2.18) and PFOS had an odds ratio of 1.03 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.08). |

| Kristen Lyall/2018/United States [80] | Case–control Stude | n = 553 | 15–19 weeks gestational age | Et-PFOSA, Me-PFOSA, PFDeA, PFHxS, PFNA, PFOA, PFOS, PFOSA | Serum/ Negative-ion Turbo Ion Spray–tandem mass spectrometry | Et-PFOSA: 0.68 (0.63, 0.73), Me-PFOSA: 1.14 (1.07, 1.23), PFDeA: 0.17 (0.16, 0.18), PFHxS: 1.39 (1.29, 1.49), PFNA: 0.60 (0.57, 0.63), PFOA: 3.58 (3.41, 3.76), PFOS: 17.5 (16.8, 18.3), PFOSA: 0.11 (0.10, 0.11) (ng/mL) | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR) criteria | Child sex, month and year of birth, maternal age, country of maternal birth, maternal race/ethnicity, parity, and maternal education. | While most PFAS prenatal concentrations were not significantly linked to ASD, notable inverse associations were observed for perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). Specifically, the adjusted odds ratios for the highest versus lowest quartiles were 0.62 (95% CI: 0.41, 0.93) for PFOA and 0.64 (95% CI: 0.43, 0.97) for PFOS. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Currie, S.D.; Wang, J.-S.; Tang, L. Impacts of PFAS Exposure on Neurodevelopment: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Environments 2024, 11, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11090188

Currie SD, Wang J-S, Tang L. Impacts of PFAS Exposure on Neurodevelopment: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Environments. 2024; 11(9):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11090188

Chicago/Turabian StyleCurrie, Seth D., Jia-Sheng Wang, and Lili Tang. 2024. "Impacts of PFAS Exposure on Neurodevelopment: A Comprehensive Literature Review" Environments 11, no. 9: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11090188

APA StyleCurrie, S. D., Wang, J.-S., & Tang, L. (2024). Impacts of PFAS Exposure on Neurodevelopment: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Environments, 11(9), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11090188