Does the Bilingual Advantage in Cognitive Control Exist and If So, What Are Its Modulating Factors? A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

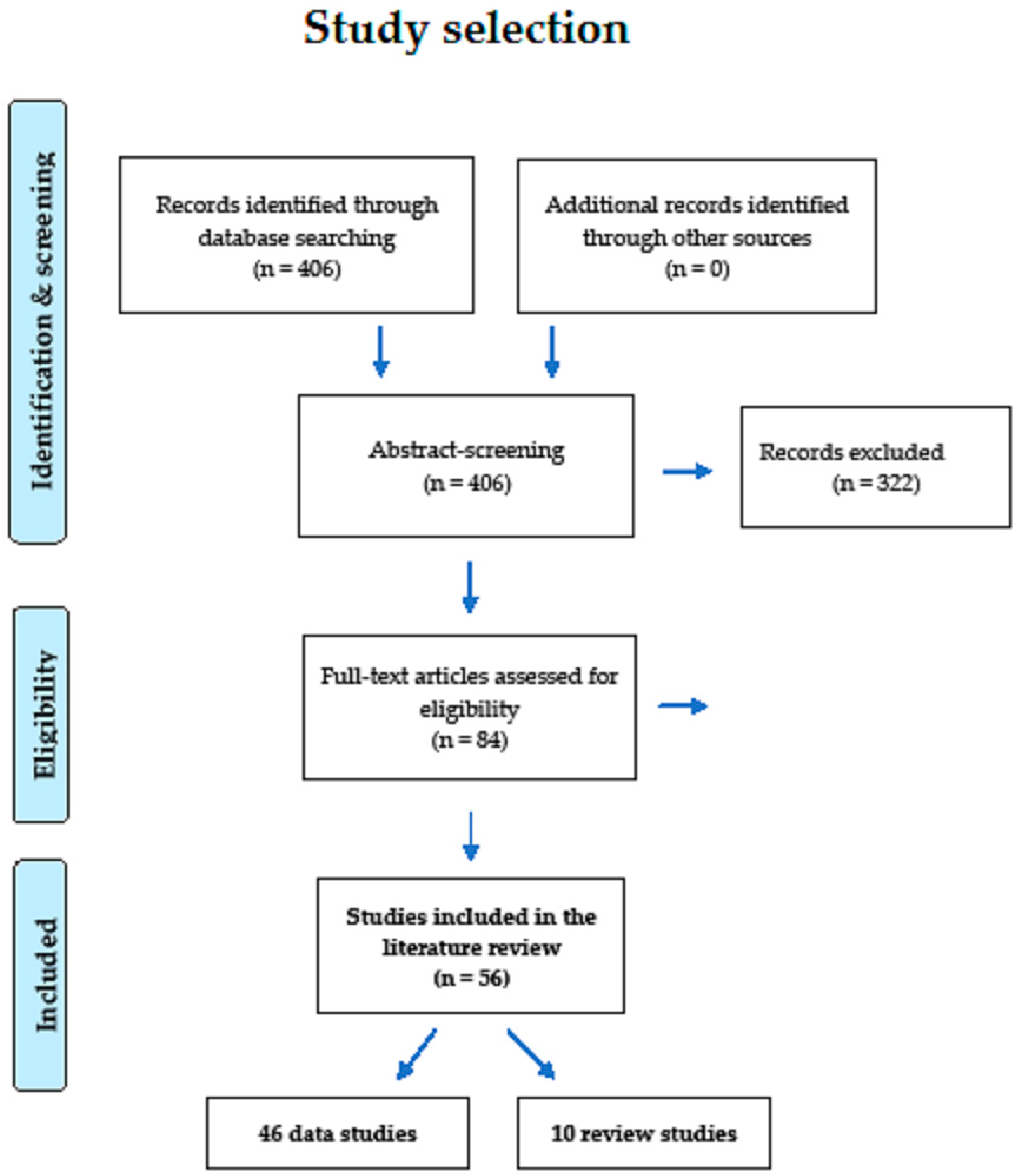

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

3. Results

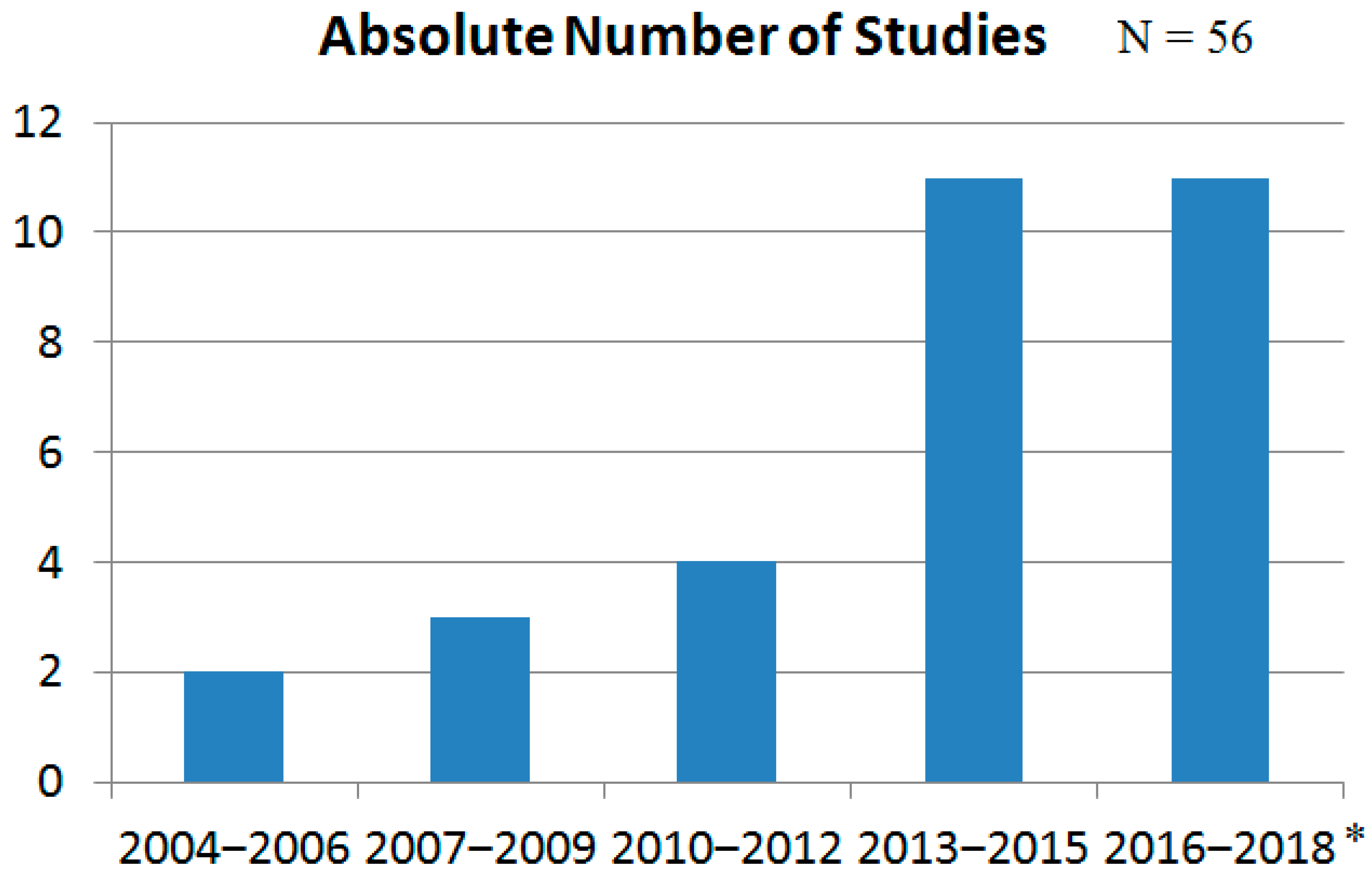

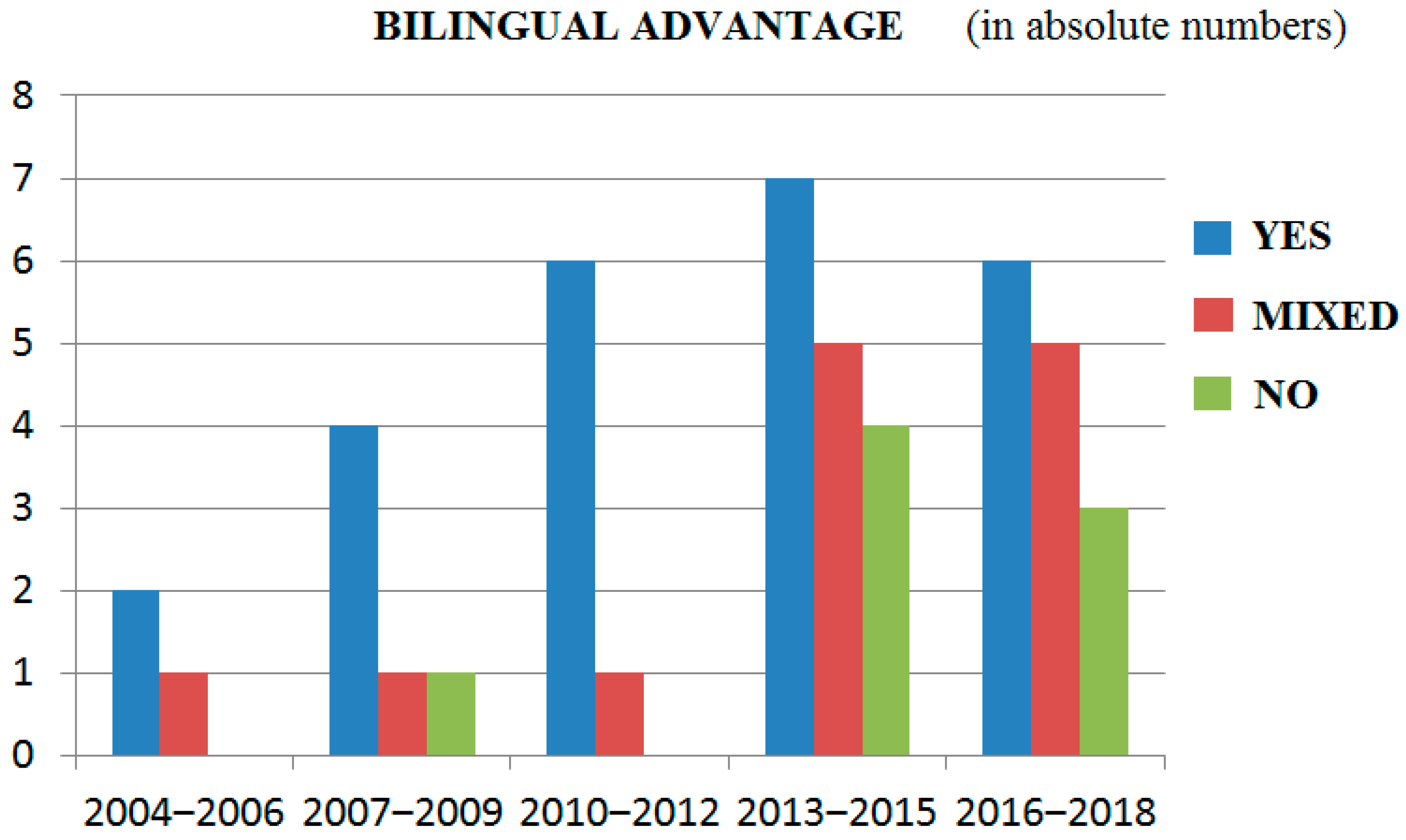

3.1. General Results

3.2. Bilingual Advantage in Children

3.3. Bilingual Advantage in Adults

3.3.1. Behavioral Results

3.3.2. Neuroimaging Results

3.4. Experimental Tasks

3.4.1. Simon Task

3.4.2. Attention Network Test

3.4.3. Flanker Task

3.4.4. Stroop Task

3.4.5. Switching Task

3.4.6. Other Experimental Tasks

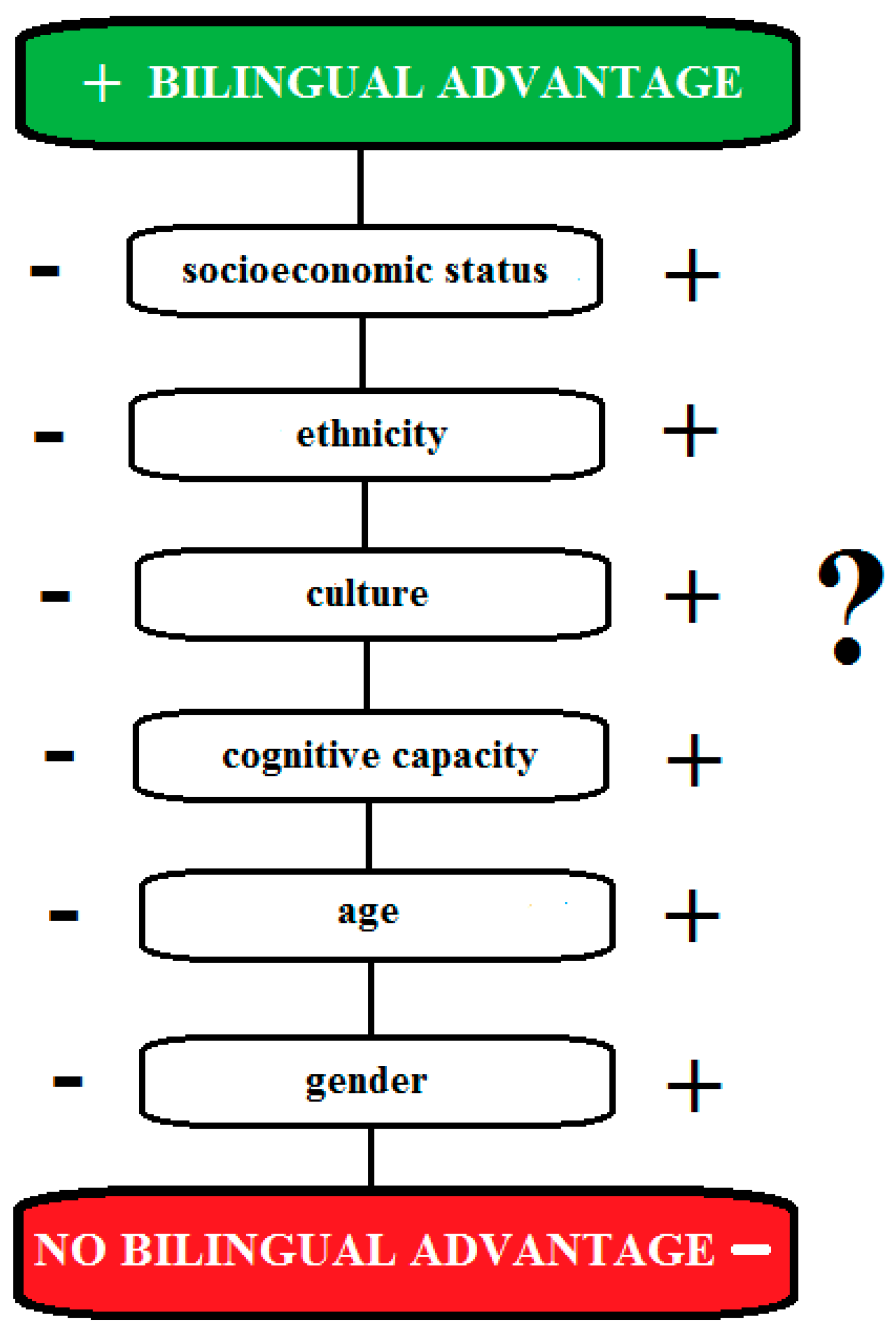

4. Discussion

4.1. General Limitations of Studies Conducted So Far

4.2. Limitations of Our Own Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ansaldo, A.I.; Marcotte, K.; Scherer, L.; Raboyeau, G. Language therapy and bilingual aphasia: Clinical implications of psycholinguistic and neuroimaging research. J. Neurolinguistics 2008, 21, 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milambiling, J. Bringing one language to another: Multilingualism as a resource in the language classroom. Engl. Teach. Forum 2011, 1, 18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, B.; Hashemi, M. Foreign language learning during childhood. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 28, 872–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.S.; Newport, E.L. Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cogn. Psychol. 1989, 21, 60–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, D.; Ryan, L. Language Acquisition: The Age Factor; Multilingual Matters Ltd.: Clevedon, PA, USA, 2004; 289p, ISBN 1853597570. [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne, J.K.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Pinker, S. A critical period for second language acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 million English speakers. Cognition 2018, 177, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struys, E.; Mohades, G.; Bosch, P.; Van den Noort, M. Cognitive control in bilingual children: Disentangling the effects of second-language proficiency and onset age of acquisition. Swiss J. Psychol. 2015, 74, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenneberg, E.H. Biological Foundations of Language; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1967; 489p, ISBN 13-978-0471526261. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, D. The critical period hypothesis: A coat of many colours. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 2005, 43, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhofe, J. The critical period hypothesis in second language acquisition: A statistical critique and a reanalysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempe, V.; Brooks, P.J. Individual differences in adult second language learning: A cognitive perspective. Scott. Lang. Rev. 2011, 23, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Friesen, D.C.; Latman, V.; Calvo, A.; Bialystok, E. Attention during visual search: The benefit of bilingualism. Int. J. Billing. 2015, 19, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, E.; Küntay, A.C.; Messer, M.; Verhagen, J.; Leseman, P. The benefits of being bilingual: Working memory in bilingual Turkish-Dutch children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2014, 128, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenfeld, H.K.; Marian, V. Cognitive control in bilinguals: Advantages in stimulus-stimulus inhibition. Bilingualism 2014, 17, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialystok, E.; Majumder, S.; Martin, M.M. Developing phonological awareness: Is there a bilingual advantage? Appl. Psycholinguist. 2003, 24, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braver, T.S. The variable nature of cognitive control: A dual mechanisms framework. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2012, 16, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, E. Bilinguals’ working memory (WM) advantage and their dual language practices. Brain Sci. 2017, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starreveld, P.A.; De Groot, A.M.B.; Rossmark, B.M.M.; Van Hell, J.G. Parallel language activation during word processing in bilinguals: Evidence from word production in sentence context. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2014, 17, 258–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutalebi, J.; Green, D.W. Control mechanisms in bilingual language production: Neural evidence from language switching studies. Lang. Cognitive Proc. 2008, 23, 557–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struys, E.; Woumans, E.; Nour, S.; Kepinska, O.; Van den Noort, M. A domain general monitoring account of language switching in recognition tasks: Evidence for adaptive control. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paap, K.R.; Greenberg, Z.I. There is no coherent evidence for a bilingual advantage in executive processing. Cogn. Psychol. 2013, 66, 232–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paap, K.R.; Myuz, H.A.; Anders, R.T.; Bockelman, M.F.; Mikulinsky, R.; Sawi, O.M. No compelling evidence for a bilingual advantage in switching or that frequent language switching reduces switch cost. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2017, 29, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratiu, I.; Azuma, T. Working memory capacity: Is there a bilingual advantage? J. Cogn. Psychol. 2015, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, K. Executive control in bilingual children: Factors that influence the outcomes. Linguist. Approaches Biling. 2016, 6, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woumans, E.; Duyck, W. The bilingual advantage debate: Moving toward different methods for verifying its existence. Cortex 2015, 73, 356–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, eb2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E.; Craik, F.I.; Klein, R.; Viswanathan, M. Bilingualism, aging, and cognitive control: Evidence from the Simon task. Psychol. Aging 2004, 19, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialystok, E.; Craik, F.I.; Grady, C.; Chau, W.; Ishii, R.; Gunji, A.; Pantev, C. Effect of bilingualism on cognitive control in the Simon task: Evidence from MEG. NeuroImage 2005, 24, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. Effect of bilingualism and computer video game experience on the Simon task. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 2006, 60, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.B.; Harper, S.N. What did Simon say? Revisiting the bilingual advantage. Dev. Sci. 2007, 10, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialystok, E.; Craik, F.I.; Luk, G. Cognitive control and lexical access in younger and older bilinguals. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2008, 34, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmorey, K.; Luk, G.; Pyers, J.E.; Bialystok, E. The source of enhanced cognitive control in bilinguals: Evidence from bimodal bilinguals. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.; Hernández, M.; Sebastián Gallés, N. Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: Evidence from the ANT task. Cognition 2008, 106, 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialystok, E.; DePape, A.M. Musical expertise, bilingualism, and executive functioning. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2009, 35, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.; Hernández, M.; Costa-Faidella, J.; Sebastián Gallés, N. On the bilingual advantage in conflict processing: Now you see it, now you don’t. Cognition 2009, 113, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E.; Barac, R.; Blaye, A.; Poulin-Dubois, D. Word mapping and executive functioning in young monolingual and bilingual children. J. Cogn. Dev. 2010, 11, 485–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbin, G.; Sanjuan, A.; Forn, C.; Bustamante, J.C.; Rodriguez-Pujadas, A.; Belloch, V.; Hernandez, M.; Costa, A.; Avila, C. Bridging language and attention: Brain basis of the impact of bilingualism on cognitive control. NeuroImage 2010, 53, 1272–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Luk, G.; Bialystok, E. Effect of language proficiency and executive control on verbal fluency performance in bilinguals. Cognition 2010, 114, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soveri, A.; Laine, M.; Hämäläinen, H.; Hugdahl, K. Bilingual advantage in attentional control: Evidence from the forced-attention dichotic listening paradigm. Bilingualism 2011, 14, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Marzecová, A.; Taft, M.; Asanowicz, D.; Wodniecka, Z. The efficiency of attentional networks in early and late bilinguals: The role of age of acquisition. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudes, C.; Macizo, P.; Bajo, T. The influence of expertise in simultaneous interpreting on non-verbal executive processes. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel de Abreu, P.M.; Cruz-Santos, A.; Tourinho, C.J.; Martin, R.; Bialystok, E. Bilingualism enriches the poor: Enhanced cognitive control in low-income minority children. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzecová, A.; Bukowski, M.; Correa, Á.; Boros, M.; Lupiáñez, J.; Wodniecka, Z. Tracing the bilingual advantage in cognitive control: The role of flexibility in temporal preparation and category switching. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2013, 25, 586–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.L. Effects of bilingualism and trilingualism in L2 production: Evidence from errors and self-repairs in early balanced bilingual and trilingual adults. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2014, 43, 357–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macnamara, B.N.; Conway, A.R. Novel evidence in support of the bilingual advantage: Influences of task demands and experience on cognitive control and working memory. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2014, 21, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duñabeitia, J.A.; Hernández, J.A.; Antón, E.; Macizo, P.; Estévez, A.; Fuentes, L.J.; Carreiras, M. The inhibitory advantage in bilingual children revisited: Myth or reality? Exp. Psychol. 2014, 61, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coderre, E.L.; van Heuven, W.J. The effect of script similarity on executive control in bilinguals. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kousaie, S.; Sheppard, C.; Lemieux, M.; Monetta, L.; Taler, V. Executive function and bilingualism in young and older adults. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, N.W.; Fiala, L.; Scott-Brown, K.C.; Kempe, V. No evidence for reduced Simon cost in elderly bilinguals and bidialectals. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2014, 26, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansaldo, A.I.; Ghazi-Saidi, L.; Adrover-Roig, D. Interference control in elderly bilinguals: Appearances can be misleading. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2015, 37, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervais-Adelman, A.; Moser-Mercer, B.; Michel, C.M.; Golestani, N. fMRI of simultaneous interpretation reveals the neural of extreme language control. Cereb. Cortex 2015, 25, 4727–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woumans, E.; Ceuleers, E.; Van der Linden, L.; Szmalec, A.; Duyck, W. Verbal and nonverbal cognitive control in bilinguals and interpreters. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2015, 41, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousaie, S.; Laliberté, C.; López Zunini, R.; Taler, V. A behavioral and electrophysiological investigation of the effect of bilingualism on lexical ambiguity resolution in young adults. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poarch, G.J.; Bialystok, E. Bilingualism as a model for multitasking. Dev. Rev. 2015, 35, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goral, M.; Campanelli, L.; Spiro, A. Language dominance and inhibition abilities in bilingual older adults. Bilingualism 2015, 18, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Elorrieta, E.; Pylkkänen, L. Bilingual language control in perception versus action: MEG reveals comprehension control mechanisms in anterior cingulate cortex and domain-general control of production in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.R.; Bak, T.H.; Allerhand, M.; Redmond, P.; Starr, J.M.; Deary, I.J.; MacPherson, S.E. Bilingualism, social cognition and executive functions: A tale of chickens and eggs. Neuropsychologia 2016, 91, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teubner-Rhodes, S.E.; Mishler, A.; Corbett, R.; Andreu, L.; Sanz-Torrent, M.; Trueswell, J.C.; Novick, J.M. The effects of bilingualism on conflict monitoring, cognitive control, and garden-path recovery. Cognition 2016, 150, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Liu, Y. Classes in translating and interpreting produce differential gains in switching and updating. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, S.R.; Marian, V.; Shook, A.; Bartolotti, J. Bilingualism and musicianship enhance cognitive control. Neural. Plast. 2016, 2016, 4058620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, H.L. An interaction between the effects of bilingualism and cross-linguistic similarity in balanced and unbalanced bilingual adults’ L2 Mandarin word reading production. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2017, 46, 935–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Elorrieta, E.; Pylkkänen, L. Bilingual language switching in the laboratory versus in the wild: The spatiotemporal dynamics of adaptive language control. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 9022–9036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousaie, S.; Phillips, N.A. A behavioural and electrophysiological investigation of the effect of bilingualism on aging and cognitive control. Neuropsychologia 2017, 94, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desideri, L.; Bonifacci, P. Verbal and nonverbal anticipatory mechanisms in bilinguals. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2018, 47, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z. The influence of second language (2) proficiency on cognitive control among young adult unbalanced Chinese-English bilinguals. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struys, E.; Duyck, W.; Woumans, E. The role of cognitive development and strategic task tendencies in the bilingual advantage controversy. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, K.; Filippi, R.; Periche-Tomas, E.; Papageorgiou, A.; Bright, P. The importance of socioeconomic status as a modulator of the bilingual advantage in cognitive ability. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, L.; Van de Putte, E.; Woumans, E.; Duyck, W.; Szmalec, A. Does extreme language control training improve cognitive control? A comparison of professional interpreters, L2 teachers and monolinguals. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, J.L.; Fernandez, F. Performance on auditory and visual tasks of inhibition in English monolingual and Spanish-English bilingual adults: Do bilinguals have a cognitive advantage? J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2018, 61, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesope, O.O.; Lavin, T.; Thompson, T.; Ungerleider, C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the cognitive correlates of bilingualism. Rev. Educ. Res. 2010, 80, 207–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilchey, M.D.; Klein, R.M. Are there bilingual advantages on nonlinguistic interference tasks? Implications for the plasticity of executive control processes. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2011, 18, 625–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.; Dennis, N.A.; Li, P. Cognitive control, cognitive reserve, and memory in the aging bilingual brain. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruin, A.; Treccani, B.; Della Sala, S. Cognitive advantage in bilingualism: An example of publication bias? Psychol. Sci. 2015, 49, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, A.E.; Greene, M.R.; Vaughn, K.A.; Francis, D.J.; Grigorenko, E.L. Beyond the bilingual advantage: The potential role of genes and environment on the development of cognitive control. J. Neurolinguistics 2015, 35, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paap, K.R.; Johnson, H.A.; Sawi, O. Bilingual advantages in executive functioning either do not exist or are restricted to very specific and undetermined circumstances. Cortex 2015, 69, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Krott, A. Data trimming procedure can eliminate bilingual cognitive advantage. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2016, 23, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehtonen, M.; Soveri, A.; Laine, A.; Järvenpää, J.; de Bruin, A.; Antfolk, J. Is bilingualism associated with enhanced executive functioning in adults? A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 394–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahesu Tabori, A.A.; Mech, E.N.; Atagi, N. Exploiting language variation to better understand the cognitive consequences of bilingualism. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, S.; Roehr-Brackin, K.; Pak, H.; Kim, H. Cultural effects rather than a bilingual advantage in cognition: A review and an empirical study. Cogn. Sci. 2018, 42, 2313–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, J.R.; Rudell, A.P. Auditory S-R compatibility: The effect of an irrelevant cue on information processing. J. Appl. Psychol. 1967, 51, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; McCandliss, B.D.; Sommer, T.; Raz, A.; Posner, M.I. Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2002, 14, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, B.A.; Eriksen, C.W. Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Percept. Psychophys. 1974, 16, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroop, J.R. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. 1935, 18, 643–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Janse, E.; Visser, K.; Meyer, A.S. What do verbal fluency tasks measure? Predictors of verbal fluency performance in older adults. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchner, W.K. Age differences in short-term retention of rapidly changing information. J. Exp. Psychol. 1958, 55, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, D.A.; Berg, E.A. A behavioral analysis of degree of reinforcement and ease of shifting to new responses in a Weigl-type card-sorting problem. J. Exp. Psychol. 1948, 38, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, K.W.; Byrd, D.L. The tower of London spatial problem-solving task: Enhancing clinical and research implementation. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2002, 24, 586–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. WAIS-III Nederlandstalige Bewerking: Afname-en Scoringshandleiding, [WAIS-III Dutch version: User manual]; Swets and Zeitlinger: Lisse, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Szmalec, A.; Duyck, W.; Vandierendonck, A.; Mata, A.B.; Page, M.P. The Hebb repetition effect as a laboratory analogue of novel word learning. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2009, 62, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A.; Taylor, C. Development of an aspect of executive control: Development of the abilities to remember what I said and to “do as I say, not as I do”. Dev. Psychobiol. 1996, 29, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manly, T.; Robertson, I.H.; Anderson, V.; Nimmo-Smith, I. The Test of Everyday Attention for Children (TEA-Ch); Battley Brothers: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, S.M.; Mandell, D.J.; Williams, L. Executive function and theory of mind: Stability and prediction from ages 2 to 3. Dev. Psychol. 2004, 40, 1105–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I.H.; Manly, T.; Andrade, J.; Baddeley, B.T.; Yiend, J. ‘Oops!’: Performance correlates of everyday attentional failures in traumatic brain injured and normal subjects. Neuropsychologia 1997, 35, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreen, O.; Strauss, E. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; 442p, ISBN 0195054393. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, D. Cerebral dominance and the perception of verbal stimuli. Can. J. Psychol. 1961, 15, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller-Thomson, E. Emerging evidence contradicts the hypothesis that bilingualism delays dementia onset. A Commentary on “Age of dementia diagnosis in community dwelling bilingual and monolingual Hispanic Americans” by Lawton et al., 2015. Cortex 2015, 66, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, D.M.; Gasquoine, P.G.; Weimer, A.A. Age of dementia diagnosis in community dwelling bilingual and monolingual Hispanic Americans. Cortex 2015, 66, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, S.M.; Choi, H.P. Bilingual and bicultural: Executive function in Korean and American children. Presented at the 2009 Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Denver, CO, USA, 2–4 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stuss, D.T.; Knight, R.T. Principles of Frontal Lobe Function; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; 640p, ISBN 978-0195134971. [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson, S.E.; Della Sala, S. Handbook of Frontal Lobe Assessment; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; 448p, ISBN 9780199669523. [Google Scholar]

- Valian, V. Bilingualism and cognition. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2015, 18, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradowski, M.B. The bilingual advantage debate. In M/Other Tongues in Language Acquisition, Instruction, and Use; Paradowski, M.B., Ed.; University of Warsaw, Institute of Applied Linguistics: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; pp. 252–259. ISBN 9788393532070. [Google Scholar]

- von Bastian, C.C.; Souza, A.S.; Gade, M. No evidence for bilingual cognitive advantages: A test of four hypotheses. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2016, 145, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winerman, L. Psychologists embrace open science: The field is working to change cultural norms to encourage more data sharing and open science. Monitor Psychol. 2017, 48, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Therrien, W.J.; Cook, B.G. Introduction to special issue: Null effects and publication bias in learning disabilities research. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2018, 33, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Azanza, V.A.; López-Penadés, R.; Buil-Legaz, L.; Aguilar-Mediavilla, E.; Adrover-Roig, D. Is bilingualism losing its advantage? A bibliometric approach. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunge, S.A.; Dudukovic, N.M.; Thomason, M.E.; Vaidya, C.J.; Gabrieli, J.D.E. Immature frontal lobe contributions to cognitive control in children: Evidence from fMRI. Neuron 2002, 33, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.S.; Skrondal, A. The Cambridge Dictionary of Statistics, 4th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 1–480. ISBN 13-978-0521766999. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, S.R.; Marian, V. A bilingual advantage for episodic memory in older adults. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2012, 24, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bak, T.H.; Nissan, J.J.; Allerhand, M.M.; Deary, I.J. Does bilingualism influence cognitive aging? Ann. Neurol. 2014, 75, 959–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E.; Craik, F.I.; Freedman, M. Bilingualism as a protection against the onset of symptoms of dementia. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alladi, S.; Bak, T.H.; Duggirala, V.; Surampudi, B.; Shailaja, M.; Shukla, A.K.; Chaudhuri, J.R.; Kaul, S. Bilingualism delays age at onset of dementia, independent of education and immigration status. Neurology 2013, 81, 1938–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramscar, M.; Hendrix, P.; Shaoul, C.; Milin, P.; Baayen, H. The myth of cognitive decline: Non-linear dynamics of lifelong learning. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2014, 6, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabria, M.; Hernández, M.; Martin, C.D.; Costa, A. When the tail counts: The advantage of bilingualism through the ex-Gaussian distribution analysis. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughn, K.A.; Greene, M.R.; Ramos Nuñez, A.I.; Hernandez, A.E. The importance of neuroscience in understanding bilingual cognitive control. Cortex 2015, 73, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alageel, S.; Sheft, S.; Shafiro, V. Linguistic masking release in young and older adults with age-appropriate hearing status. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2017, 142, EL155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakuta, J. Mirror of Language: The Debate of Bilingualism; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1986; 288p, ISBN 978-0465046379. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, R.M. What cognitive processes are likely to be exercised by bilingualism and does this exercise lead to extra-linguistic cognitive benefits? Linguist. Approaches Biling. 2016, 6, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, M.; Lehtonen, M. Cognitive consequences of bilingualism: Where to go from here? Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018, 33, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treccani, B.; Mulatti, C. No matter who, no matter how… and no matter whether the white matter matters. Why theories of bilingual advantage in executive functioning are so difficult to falsify. Cortex 2015, 73, 349–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Malhotra, N.; Simonovits, G. Publication bias in the social sciences: Unlocking the file drawer. Science 2014, 345, 1502–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mervis, J. Why null results rarely see the light of day. Science 2014, 345, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edglossery. Norm-Referenced Test. Available online: https://www.edglossary.org/norm-referenced-test/ (accessed on 10 November 2018).

- Vaughn, K.A.; Hernandez, A.E. Becoming a balanced, proficient bilingual: Predictions from age of acquisition and genetic background. J. Neurolinguistics 2018, 46, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughn, K.A.; Ramos Nuñez, A.I.; Greene, M.R.; Munson, B.A.; Grigorenko, E.L.; Hernandez, A.E. Individual differences in the bilingual brain: The role of language background and DRD2 genotype in verbal and non-verbal cognitive control. J. Neurolinguistics 2016, 40, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Putte, E.; De Baene, W.; García-Pentón, L.; Woumans, E.; Dijkgraaf, A.; Duyck, W. Anatomical and functional changes in the brain after simultaneous interpreting training: A longitudinal study. Cortex 2018, 99, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Noort, M.; Struys, E.; Kim, K.-Y.; Bosch, P.; Mondt, K.; Van Kralingen, R.; Lee, M.-K.; Van de Craen, P. Multilingual processing in the brain. Int. J. Multiling. 2014, 11, 182–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Steinkrauss, R.; Van der Steen, S.; Cox, R.; De Bot, K. Foreign language learning as a complex dynamic process: A microgenetic case study of a Chinese child’s English learning trajectory. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2016, 49, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullberg, M.; Roberts, L.; Dimroth, C.; Veroude, K.; Indefrey, P. Adult language learning after minimal exposure to an unknown natural language. Lang. Learn. 2010, 60, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M. Power problems: N > 138. Cortex 2015, 73, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paap, K.R.; Johnson, H.A.; Sawi, O. Should the search for bilingual advantages in executive functioning continue? Cortex 2016, 74, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. Claiming evidence from non-evidence: A reply to Morton and Harper. Dev. Sci. 2009, 12, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmont, J.; Struys, E.; Van den Noort, M.; Van de Craen, P. The effects of CLIL on mathematical content learning: A longitudinal study. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2016, 6, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.R.; Zhang, S.; Duann, J.R.; Yan, P.; Sinha, R.; Mazure, C.M. Gender differences in cognitive control: An extended investigation of the Stop-Signal task. Brain Imaging Behav. 2009, 3, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huster, R.J.; Westerhausen, R.; Herrmann, C.S. Sex differences in cognitive control are associated with midcingulate and callosal morphology. Brain Struct. Funct. 2011, 215, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rama, T. Phonotactic diversity predicts the time depth of the world’s language families. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vangsnes, Ø.A.; Söderlund, G.B.W.; Blekesaune, M. The effect of bidialectal literacy on school achievement. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2017, 20, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, K.; Grohmann, K.K.; Kambanaros, M.; Katsos, N. The effect of childhood bilectalism and multilingualism on executive control. Cognition 2016, 149, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors/Publication Year | Number of Bilingual Subjects | Type of Cognitive Control Task | Results | Bilingual Advantage | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bialystok et al., 2004 [27] | 20 young adults and 20 older adults | Simon task | Smaller Simon effect costs were found for both the young adult and the older adult bilingual group. Moreover, the bilinguals responded more rapidly to conditions that placed greater demands on working memory than the monolinguals. | YES | The authors conclude that controlled processing is carried out more effectively by bilinguals. Secondly, bilingualism helps to offset age-related losses in certain executive processes. |

| Bialystok et al., 2005 [28] | 20 young adults | Simon task | The MEG results showed that correlations between activated regions and reaction times demonstrated faster reaction times with greater activity in different brain regions in bilinguals compared to monolinguals. | PARTIAL | The management of two language systems led to systematic changes in frontal executive functions. |

| Bialystok, 2006 [29] | 57 young adults | Simon task | Video-game players showed faster responses in almost all conditions; however, bilingual adults were found to be faster than the video-game players in a condition that required the most controlled attention to resolve conflict. | YES | Support was found for the bilingual advantage in cognitive control. |

| Morton, Harper, 2007 [30] | 17 children | Simon task | Bilingual and monolingual children performed identically. Children from higher socioeconomic status families performed better than children from lower socioeconomic status families. | NO | Controlling for socioeconomic status and ethnicity seemed to eliminate the bilingual advantage. |

| Bialystok et al., 2008 [31] | 24 young and 24 older adults | Simon task, Stroop task, Sustained Attention to Response task | Bilinguals performed better than monolinguals on the executive functioning tasks, and this advantage was stronger in the group of older bilinguals. Their working memory performance was the same. The monolinguals outperformed the bilinguals on lexical retrieval tasks. | YES | The executive functioning results are support for the bilingual advantage in cognitive control hypothesis; the bilinguals outperformed the monolinguals. |

| Emmorey et al., 2008 [32] | 30 middle-aged adults | Flanker tasks | No group differences in accuracy were found. However, the unimodal bilinguals were faster than the bimodal bilinguals and the monolinguals. | PARTIAL | The bilingual advantage in cognitive control is the result of the unimodal bilingual’s experience controlling two languages in the same modality. |

| Costa et al., 2008 [33] | 100 young adults | Attention Network Test | Bilinguals were faster on the attention network test than the monolinguals; moreover, they were more efficient in alerting and executive control. Bilinguals were better in dealing with conflicting information and showed a reduced switching cost as compared to the monolinguals. | YES | Bilinguals have more efficient attentional mechanisms than monolinguals. This finding supports the bilingual advantage hypothesis. |

| Bialystok, DePape, 2009 [34] | 24 young adults | Simon task, Stroop task | The bilingual adults and monolingual musicians performed better than the monolingual adults on the Simon task. Moreover, the monolingual musicians outperformed the monolingual and bilingual adults on the Stroop task. | YES | The results on the Simon task are support for the bilingual advantage. In addition, musicians were found to have enhanced control in a more specialized auditory task; this was not the case for the bilingual adults. |

| Costa et al., 2009 [35] | 122 young adults | Flanker task | The bilinguals were faster than the monolinguals in the high-monitoring condition, but not in the low-monitoring condition. | YES | Support was found for the hypothesis that bilingualism may affect the monitoring processes involved in executive control. |

| Bialystok et al., 2010 [36] | 56 children | Attention Network Test, Luria’s tapping task, Opposite Worlds task, reverse categori- zation task | The bilingual children performed better on the Luria’s tapping task, opposite worlds task, and reverse categorization task than the monolingual children. On the attention network test, no differences in scores between the bilingual and the monolingual children were found. | YES | Evidence was found for a bilingual advantage in several aspects of executive functioning in young children. This bilingual advantage is present at an earlier age than was previously reported in the literature. |

| Garbin et al., 2010 [37] | 19 young adults | Nonlinguistic Switching task | A reduced switching cost was found in the bilinguals. The bilinguals activated the left inferior frontal cortex and the left striatum, areas that are known to be involved in language control. | YES | The early training of bilinguals in language switching (back and forth) leads to the activation of brain regions known to be involved in language control when conducting nonlinguistic cognitive tasks. |

| Luo et al., 2010 [38] | 40 young adults | Verbal fluency tasks | The letter fluency results showed enhanced executive control for bilinguals compared to monolinguals. No differences between bilinguals and monolinguals were found in category fluency. | YES | The bilinguals showed enhanced executive control on the letter fluency task, supporting the bilingual advantage hypothesis. |

| Soveri et al., 2011 [39] | 33 adults varying from young to older | Dichotic listening task | Early simultaneous bilinguals outperformed the monolinguals in the forced-attention dichotic listening task; better scores in the forced-right and forced-left attention conditions were found. | YES | Early simultaneous bilinguals are better than monolinguals in directing attention and in inhibiting task-irrelevant stimuli, supporting the bilingual advantage hypothesis. |

| Tao et al., 2011 [40] | 66 young adults | Attention Network Test | Both early and late bilinguals had an advantage in conflict resolution compared to monolinguals; the greatest advantage was found for the early bilinguals. | YES | Specific factors of language experience may affect cognitive control differently. |

| Yudes et al., 2011 [41] | 32 young to middle-aged adults | Simon task, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | Simultaneous interpreters showed better cognitive flexibility scores than bilinguals and monolinguals; however, no differences in inhibition scores were found. | PARTIAL | Some evidence in favor of the bilingual advantage was found. Interpreters indeed outperformed the monolinguals in cognitive flexibility. However, the inhibition results showed a different picture; the interpreters, bilinguals, and monolinguals showed similar results, which is not what the bilingual advantage hypothesis would predict. |

| Engel de Abreu et al., 2012 [42] | 40 children | Complex and simple WM tasks, selective attention test, Flanker task | The bilinguals were better than the monolinguals in cognitive control. | YES | The bilingual advantage was found after controlling for socioeconomic and cultural factors. The bilingual advantage was found for cognitive control and not in other domains. |

| Marzecová et al., 2013 [43] | 22 young adults | Switching tasks | Bilinguals were found to be less affected by the duration of the preceding preparatory interval compared to monolinguals. Moreover, bilinguals outperformed monolinguals on the category switch task; reduced switch costs and greater accuracy scores were found. | YES | Bilingualism was positively found to influence the mechanisms of cognitive flexibility. |

| Paap, Greenberg, 2013 [21] | 122 young adults | Simon task, Flanker task, Switching task | No evidence was found for consistent cross-task advantages in executive processing for the bilinguals compared to the monolinguals. | NO | No consistent cross-task correlations were found, showing evidence against the existence of a bilingual advantage in executive processing. |

| Hsu, 2014 [44] | 78 young adults | Speech production tasks | The first experiment showed that bilinguals and trilinguals outperformed monolinguals in all aspects of inhibitory control. The second experiment showed only an advantage in attentional control for the trilinguals. | YES | The advantage in inhibitory control was visible in more contexts for the trilinguals than for the bilinguals. |

| Macnamara, Conway, 2014 [45] | 21 young adults | Switching task, Mental flexibility task, WM tasks | The adult bimodal bilinguals were followed and re-tested for two years. During this time, their cognitive abilities associated with managing the bilingual demands improved. | YES | The mechanisms recruited during bilingual management and the amount of experience managing the bilingual demands are underlying factors of the bilingual advantage on cognitive control. |

| Duñabeitia et al., 2014 [46] | 252 children | Stroop task | No differences in inhibitory performance scores were found between the bilingual and the monolingual children. | NO | No evidence was found for a bilingual advantage on simple inhibitory tasks. |

| Coderre, van Heuven, 2014 [47] | 58 young adults | Simon task, Stroop task | The similar-script bilinguals were found to have more effective domain-general executive control than the different-script bilinguals. | PARTIAL | No consistent evidence for a bilingual advantage was found, only global response time effects. Script similarity is an important variable to control. |

| Blumenfeld, Marian, 2014 [14] | 90 young adults | Simon task, Stroop task | The bilinguals performed better on the Stroop task than on the Simon task. The monolinguals did not perform differently on the two cognitive control tasks. | YES | Evidence was found for a bilingual advantage in cognitive control where bilingualism may be especially likely to modulate cognitive control mechanisms resolving the stimulus–stimulus competition between two dimensions of the same stimulus. |

| Kousaie et al., 2014 [48] | 51 young adults and 36 older adults | Simon task, Stroop task, Sustained Attention to Response task, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | In some executive functioning tasks, the bilinguals outperformed the monolinguals, but these findings were not consistent across executive function tasks. Moreover, no disadvantage was found for bilinguals on language tasks. Finally, evidence was found that language environment might be an important modulating factor. | PARTIAL | Although in some executive functioning tasks, the bilinguals do outperform the monolinguals, these findings are not consistent across tasks. Language environment seems to be an important modulating factor. |

| Kirk et al., 2014 [49] | 32 older adults | Simon task | The bilinguals, bidialectals, and monolinguals showed no differences in overall reaction times or in the Simon effect. | NO | No evidence was found for a bilingual or bidialectal advantage in executive control. |

| Ansaldo et al., 2015 [50] | 10 older adults | Simon task | No differences in behavioral scores between the monolinguals and the bilinguals in cognitive control performance were found. However, interestingly, in contrast to the elderly monolinguals, the elderly bilinguals were found to deal with interference control without recruiting a circuit that is particularly vulnerable to aging. | PARTIAL | On the one hand, the neuroimaging results are support for the bilingual advantage hypothesis; on the other hand, the behavioral results show no support for any bilingual advantages in cognitive control. |

| Hervais-Adelman et al., 2015 [51] | 50 young adults | Simultan- eous inter- pretation and repetition | The caudate nucleus was found to be implicated in the overarching selection and control of the lexicosemantic system in interpretation while the putamen was found to be implicated in ongoing control of language output. | YES | A clear dissociation of specific dorsal striatum structures in multilingual language control was found areas that are known to be involved in nonlinguistic executive control. |

| Woumans et al., 2015 [52] | 93 young adults | Simon task, Attention Network Test | The bilingual participants showed a smaller congruency effect in the Simon task and were overall faster on the attention network test in comparison with the monolinguals. | YES | Support was found for the bilingual advantage; moreover, different patterns of bilingual language use affect the nature and extent of this advantage. |

| Struys et al., 2015 [7] | 34 children | Simon task, verbal fluency task | A higher global accuracy score was found on the Simon task for the simultaneous bilingual children compared to the early bilingual children. No differences in mean reaction time were found between the two bilingual groups. | PARTIAL | No advantage in terms of verbal fluency was found. However, simultaneous bilingual children have an advantage on the Simon task, even over early bilingual children and when L2 is controlled. |

| Kousaie et al., 2015 [53] | 17 young adults | Stroop task, Animacy Judgment task, lexical ambiguity task | No behavioral differences between the bilingual and the monolingual adults were found. However, subtle processing differences were visible in the electrophysiological data. | NO | Monolinguals rely more on context in the processing of homonyms, while bilinguals simultaneously activate both meanings. |

| Poarch, Bialystok, 2015 [54] | 143 bilingual children | Flanker task, | The bilinguals showed better scores than the monolinguals on the conflict trials in the Flanker task. The degree of bilingual experience was not found to play an important role. | YES | Evidence was found for a bilingual advantage in executive functioning. Moreover, the degree of bilingualism experience does not seem to play an important role in this bilingual advantage. |

| Goral et al., 2015 [55] | 106 middle-aged to older adults | Simon task, Trail Making test | Balanced bilingual adults showed a greater Simon effect with increasing age, but this was not the case for the dominant bilingual adults. | PARTIAL | Mixed results were found. On the one hand, the results of the dominant bilinguals support the bilingual advantage hypothesis; on the other hand, the results of the balanced bilinguals showed age-related inhibition decline. |

| Blanco-Elorrieta, Pylkkänen, 2016 [56] | 19 young adults | Switching tasks | The bilingual results show a clear dissociation of language control mechanisms in production versus comprehension. | PARTIAL | Partial support was found for the bilingual advantage; language control is a subdomain of general executive control in production. |

| Cox et al., 2016 [57] | 26 bilingual older adults | Simon task | The bilinguals outperformed the monolinguals on the Simon task. This bilingual advantage in conflict processing remained after controlling for the influence of childhood intelligence, as well as the parents’ and the child’s social class. | YES | Evidence was found for the bilingual advantage in the cognitive control hypothesis. L2 learning was found to be related to better conflict processing. Moreover, neither initial childhood ability nor social class was found to be a modulating factor. |

| Teubner-Rhodes et al., 2016 [58] | 59 young adults | N-back task | Bilinguals performed better than monolinguals on a high-conflict task; however, this was not the case on a no-conflict version of the N-back task and on sentence comprehension. | YES | Evidence was found for the bilingual advantage. This advantage may suggest better cognitive flexibility skills. |

| Dong, Liu, 2016 [59] | 145 young adults | Stroop task, switching task, N-back task | The bilinguals with interpreting experience showed improvements in switching and updating performance, while the bilinguals with translating experience showed only marginally significant improvements in updating. | YES | Processing demand was found to be a modulating factor for the presence or absence of bilingual advantages. |

| Schroeder et al., 2016 [60] | 112 young adults | Simon task | The bilinguals, musicians, and bilingual musicians showed improved executive control skills compared to the monolinguals. | YES | Evidence was found for the existence of a bilingual advantage in executive control as well as for musicians. |

| Hsu, 2017 [61] | 64 young to middle-aged adults | A reading task | The balanced and unbalanced bilinguals were better than the monolinguals on the noncontextual single-character reading task (regardless of their first language background) but not on the contextual multiword task. Finally, the unbalanced bilinguals performed better on the noncontextual task than the other two groups. | YES | The two bilingualism effects dynamically interplayed (depending on the task contexts and the relative degrees of using the first language and L2), and both affected the bilingual advantage. |

| Blanco-Elorrieta, Pylkkänen, 2017 [62] | 19 young adults | Switching tasks | The results of the bilinguals showed that switching under external constraints heavily recruited prefrontal control regions. This result is in sharp contrast with natural, voluntary switching when the prefrontal control regions are less recruited. | PARTIAL | Partial evidence was found for the bilingual advantage. This was only visible when bilinguals needed to control their languages according to external cues and not when switching was fully free. |

| Kousaie, Phillips, 2017 [63] | 22 older adults | Stroop task, Simon task, Flanker task | Bilinguals outperformed the monolinguals on the Stroop task, but no behavioral differences on the Simon and the Flanker task were found. Moreover, electrophysiological differences on all three experimental tasks were found between the bilinguals and the monolinguals. | PARTIAL | Mixed results were found. Group differences in electrophysiological results on all cognitive control tasks between the bilinguals and monolinguals were found. However, only the behavioral results on the Stroop task supported the bilingual advantage in the cognitive control hypothesis. |

| Desideri, Bonifacci, 2018 [64] | 25 young to middle-aged adults | Attention Network Test, Picture-word identifica-tion task | The bilingual adults showed overall faster reaction times and a better conflict performance. Moreover, evidence was found for a role of the nonverbal monitoring component on verbal anticipation. | YES | Bilinguals were found to have more efficient reactive processes than monolinguals. Moreover, support was found for a role of the nonverbal monitoring component on verbal anticipation. |

| Xie, 2018 [65] | 94 young adults | Flanker task, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | The Flanker results revealed a better ability of conflict monitoring for the more proficient bilinguals. The Wisconsin card sorting test showed no differences between the high-proficiency, middle-proficiency, and low-proficiency bilingual groups. | PARTIAL | The degree of L2 proficiency was found to affect conflict monitoring but had no influence on inhibition or mental set shifting. |

| Struys et al., 2018 [66] | 59 children | Simon task, Flanker task | The bilinguals performed similarly on the two cognitive control tasks compared to the monolinguals. However, only the bilinguals showed a significant speed–accuracy trade-off across tasks and age groups. | PARTIAL | Differences in strategy choices were found to be able to mask variations in performance between bilingual children and monolingual children, leading to inconsistent findings on the bilingual advantage in cognitive control. |

| Naeem et al., 2018 [67] | 45 young adults | Simon task, Tower of London task | Bilinguals were found to have shorter response times on the Simon task, without getting higher error rates. However, socioeconomic status was an important modulator of this effect. Interestingly, a monolingual advantage on the Tower of London task was found, showing higher executive planning abilities. | NO | Evidence was found against a broad bilingual advantage in executive function. Social economic status was found to be an important modulator. |

| Van der Linden et al., 2018 [68] | 25 middle-aged adults | Flanker task, Simon task, N-back task, Hebb repetition paradigm, Digit span task | The highly proficient bilinguals (interpreters and L2 teachers) did not outperform the monolinguals with respect to interference suppression, prepotent response inhibition, attention, updating, and short-term memory. | NO | No evidence was found for general cognitive control advantages in highly proficient bilinguals. Only possible advantages in short-term memory were reported. |

| Desjardins, Fernandez., 2018 [69] | 19 young adults | Dichotic listening task, Simon task | No differences in scores on any of the dichotic listening conditions were found between the bilinguals and the monolinguals. Moreover, no group differences on the visual test of inhibition were found. | NO | No evidence was found for a bilingual advantage in the inhibition of irrelevant visual and auditory information. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van den Noort, M.; Struys, E.; Bosch, P.; Jaswetz, L.; Perriard, B.; Yeo, S.; Barisch, P.; Vermeire, K.; Lee, S.-H.; Lim, S. Does the Bilingual Advantage in Cognitive Control Exist and If So, What Are Its Modulating Factors? A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9030027

van den Noort M, Struys E, Bosch P, Jaswetz L, Perriard B, Yeo S, Barisch P, Vermeire K, Lee S-H, Lim S. Does the Bilingual Advantage in Cognitive Control Exist and If So, What Are Its Modulating Factors? A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2019; 9(3):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9030027

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan den Noort, Maurits, Esli Struys, Peggy Bosch, Lars Jaswetz, Benoît Perriard, Sujung Yeo, Pia Barisch, Katrien Vermeire, Sook-Hyun Lee, and Sabina Lim. 2019. "Does the Bilingual Advantage in Cognitive Control Exist and If So, What Are Its Modulating Factors? A Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 9, no. 3: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9030027

APA Stylevan den Noort, M., Struys, E., Bosch, P., Jaswetz, L., Perriard, B., Yeo, S., Barisch, P., Vermeire, K., Lee, S.-H., & Lim, S. (2019). Does the Bilingual Advantage in Cognitive Control Exist and If So, What Are Its Modulating Factors? A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 9(3), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9030027