Psychotherapeutic Treatment of Attachment Trauma in Musicians with Severe Music Performance Anxiety

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Attachment Theory

1.2. Attachment-Informed Psychotherapy (AIP)

1.3. Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy (ISTDP)

- i.

- Inquiry and psychodiagnostic evaluation;

- ii.

- Pressure;

- iii.

- Challenge;

- iv.

- Transference resistance;

- v.

- Direct access to the unconscious;

- vi.

- Systematic analysis of the transference;

- vii.

- Dynamic exploration into the unconscious;

- viii.

- Phase of consolidation.

2. Case Vignette: Intake Assessment and Formulation

Recently, I’ve started having panic attacks… in the time leading up to a gig, I start to feel very separated and vague; my body is just reacting and I’m not quite there. It’s a really bizarre feeling and difficult to put into words … When I’m under pressure I feel really vague. …Then I get brain fog. When I know I’ve reached this point where I’m severely anxious, I get these cold flushes through my hands… For the past two years I get extremely anxious for a few weeks, … and then it passes… Relating to music, specifically last year, I was in a band that was doing a lot of really good gigs and I was at the center of it. I was writing the music; I was organizing it all. It was a seven-piece band with some really good musicians. I’d been overseas for four years travelling, and I got back at the beginning of last year—and suddenly I was confronted with having to be in some sort of musical framework and structure from week to week being at rehearsals and voice being in good condition and I just went into overload. Writing (songs) and having all the stresses that you would have, trying to lead a normal life, waking up early, being concerned about the amount of sleep I was getting. And on top of it all, my voice just shat itself. It began to freak out. That was the way that my anxiety decided to express itself, through my voice because I was the most acutely aware of it on a day-to-day basis. I entered this spiral about it…So that was all of last year—I had all the checks on more than one occasion. I’ve been to a variety of voice and ENT specialists and had laryngoscopies a bunch of times. My dad, who is an ENT specialist, took me to these doctors. They said, “No, there’s nothing there.” Anyway, so this was just an absolute roller coaster, as you can imagine. I’m trying to front more than one band. I was in three bands at the time as well…On top of it all I was coming back from India as well; I’d been overseas for a few years and I was thinking this was all intertwined and at the root of it all, everybody is telling me there is nothing wrong with my voice. And I’m going, “Well, what do I do here?” Sometimes I find it difficult to talk when I’m anxious, and it’s not like a thinking thing. I actually have trouble getting the words out. Late last year I lost one of my closest friends; she died suddenly, and it was around that time that I entered a really severe depression. There were a lot of heavy things happening and I was feeling an immense pressure on my shoulders about this musical thing. I had this amazing band… everyone in the band was saying to me, “You’ve got talent, everything is great. You’re a great songwriter. You’re a great front man. Everything is great.” But I just was systematically undoing it in my head. I just really lost faith in it all. And then this happened… my friend was travelling on a bus through […] and her body just decided that’s it, and she just died. We’d met in India and travelled together for a couple of years. I’d lived with her in […] and there was a romance… the timing was never right but one day we said we would revisit it. Then she died… that’s the bizarre thing about travel relationships—you develop these intense relationships that nobody else in the world knows about… After she died, I woke up in the morning, found no reason to get out of bed…and …considered suicide … I never actually—I was never there, never thinking to myself, “Okay, I’m going to commit suicide” but …just considering the whole meaning of it all… I never felt like I was actually going to go through with it—it was more realizing that all the things that I loved in my life were coming down around me and if I can’t sing and I can’t write music then what have I got to live for? …I had all these things that were coming up on a personal level; singing, being in a band, boiling over and then my friend died and that toppled me over the edge. All the water overflowed out of the pot. Since then, my band came apart and we unofficially broke up at the end of last year… I place the responsibility solely on myself—I brought my personal issues into the band, and I would turn up to rehearsal and not physically be able to sing, like not be able to get notes out of my mouth… and it became infectious, because nobody wanted to be in that environment, where there was no creativity and there was a really bad vibe around. In the last six months… I’ve done a full circle. I took a solid few months off gigging. I was writing music. I tried to get the band back together once or twice, but it just never happened…There’s a couple of guys in that band who are professional musicians, and that always really intimidated me because they would always put me in a situation where I didn’t feel like I belonged there. I didn’t feel like I was legitimate—I didn’t feel like I had earned my right to be there. I was saying to myself, “Why do these really great musicians want to play with me?” They believed in me, but I just butchered it… I’m not good enough. Why are these guys wanting me… they were getting us really good gigs … but I just didn’t believe in it. I thought, “As if these guys want to play music with me.” I had really no faith in myself.

2.1. Attachment History and Patterns

2.2. Internal Working Models

2.3. Affect Regulation

2.4. Transference and Countertransference

2.5. Central Dynamic Conflict (CDC)

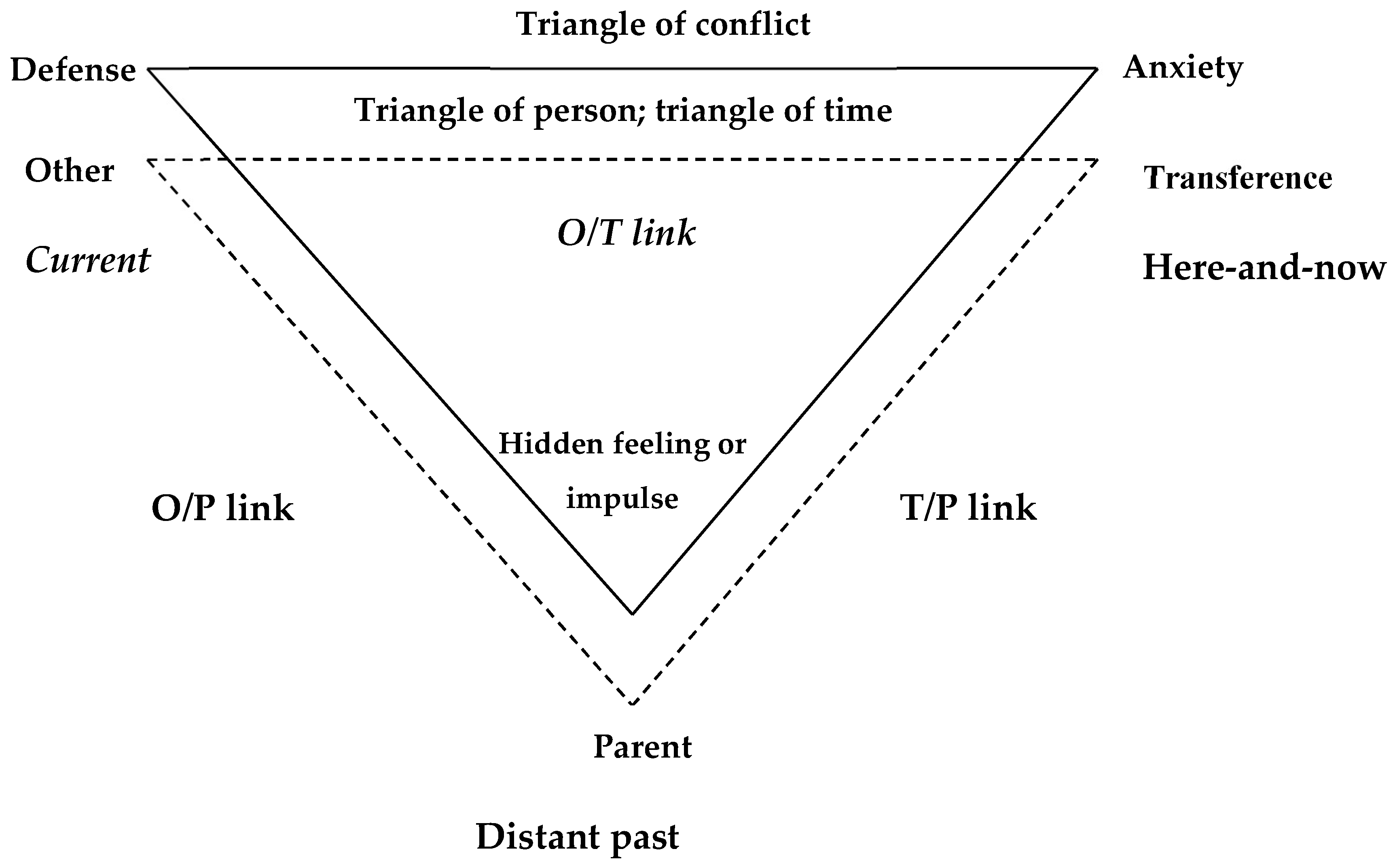

2.6. Triangle of Conflict

2.7. Treatment Goals and Interventions

2.8. A Therapist, Being Attachment-Informed

- ⮚

- Acknowledges his grief of never feeling loved: This on a background of having lost his one true love.

- ⮚

- Help him understand that his feelings are justified: Validating his need.

- ⮚

- Challenge his defenses: By identifying and labeling the behaviors.

- ⮚

- Integrate thoughts and feelings: This is the phase of meaning-making in therapy. Despite the care he exercised, his “voice just shat itself. It began to freak out. That was the way that my anxiety decided to express itself, through my voice because I was the most acutely aware of it on a day-to-day basis.” Callum’s state of disorganized attachment was embodied in his voice, which was both the nurturer/giver and the tormenter/withholder. Callum’s preoccupation with his voice and his throat could also be seen to represent a bid for his father’s attention. His father responded to Callum’s distress in an “organized insecurity” (typically avoidant) fashion (Holmes, 2010), i.e., Father was to an extent “there”, taking his son to an ENT surgeon, but perhaps in an emotionally distant and somatizing way. He was unable to respond to his son’s emotional distress. The very part of himself that Callum wanted his father to love and validate was also the part that both manifested his vulnerability, and perhaps, too, like the inconsolably crying infant, wanted to attack and debase and baffle his father in protest at his father’s emotional unresponsiveness.

3. Case Report 1: Penelope, 21, a Tertiary Level Music Student

3.1. Background

3.2. Assessment of Suitability for ISTDP

3.3. Central Dynamic Conflict (CDC)

3.4. Manifestations of Anxiety

3.5. Defenses

3.6. Transference and Capacity for Relationship

3.7. Capacity to Tolerate Anxiety and Regulate Affect

3.8. Triangle of Conflict

3.9. Triangle of Person

3.10. Interventions

3.11. Summation

- P:

- So what happened to make me feel so much better?

- DK:

- What do you think happened?

- P:

- It wasn’t just luck, was it?

- DK:

- It has nothing at all to do with luck. It is about motivation and perseverance and commitment and courage and willingness to stare these painful experiences in the face and deal with them.

- P:

- Does it have a name?

- DK:

- Well, if you want a technical term for it, “The penny dropped.”

4. Case Study 2: Kurt, 55, Professional Violinist

4.1. Background

4.2. Central Dynamic Conflict (CDC)

4.3. Manifestations of Anxiety

4.4. Defenses

4.5. Transference and Capacity for Relationship

4.6. Capacity to Tolerate Anxiety and Regulate Affect

4.7. Suitability for ISTDP

4.8. Triangle of Conflict

4.9. Triangle of Person

4.10. Therapeutic Interventions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Somatization refers to the process through which psychological distress and emotional conflict manifest as physical symptoms affecting multiple body systems (gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, respiratory, pain). These symptoms occur because emotions and anxiety are discharged into the body (via autonomic or smooth muscle pathways), resulting in chronic pain, headaches, irritable bowel, or other medically unexplained symptoms. Conversion involves the unconscious transformation of intense emotional states—often forbidden feelings like rage, guilt, or grief—into physical symptoms that cannot be explained medically. Typical conversion symptoms include sensory loss (e.g., blurred vision, numbness), movement problems (called motor conversion), such as non-epileptic seizures, loss of speech, or paralysis, none of which have an identifiable neurological cause. |

| 2 | The formulations and therapies described in this paper can only be conducted by a skilled therapist trained in psychodynamic metapsychology and AIP or ISTDP. |

| 3 | Helplessness is a regressive defense triggered by excessive anxiety. |

| 4 | Detachment refers to emotional distancing as a defense against intimacy. |

| 5 | Rationalization is typically a tactical defense that finds intellectual explanations for problems devoid of affect. |

References

- Abbass, A. (2005). Somatization: Diagnosing it sooner through emotion-focused interviewing. The Journal of Family Practice, 54(3), 231–239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abbass, A. (2008). Re: Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapies for chronic pain. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 53(10), 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, A., & Haghiri, B. (2025). Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy for functional somatic disorders: A scoping review. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 22(2), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, A., Lovas, D., & Purdy, A. (2008). Direct diagnosis and management of emotional factors in chronic headache patients. Cephalalgia, 28(12), 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, A., Town, J., & Driessen, E. (2012). Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of outcome research. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 20(2), 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, B. J., Kenny, D. T., O’Brien, I., & Driscoll, T. R. (2014). Sound practice—Improving occupational health and safety for professional orchestral musicians in Australia. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M. D. (1963). The development of mother-infant interaction among the Ganda. In B. M. Foss (Ed.), Determinants of infant behaviour (Vol. 2, pp. 67–112). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Amos, J., Furber, G., & Segal, L. (2011). Understanding maltreating mothers: A synthesis of relational trauma, attachment disorganization, structural dissociation of the personality, and experiential avoidance. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 12(5), 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelman, M. (2012). Chronic conversion disorder masking attachment disorder. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 22(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, B., Jaffe, J., Markese, S., Buck, K., Chen, H., Cohen, P., Bahrick, L., Andrews, H., & Feldstein, S. (2010). The origins of 12-month attachment: A microanalysis of 4-month mother-infant interaction. Attachment & Human Development, 12(1–2), 6–141. [Google Scholar]

- Beeber, A. R. (2018). A brief history of Davanloo’s intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 14(3), 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, A. H. (2010). New aspects of infantile trauma. PsycCRITIQUES, 55(36). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1960). Grief and mourning in infancy and early childhood. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 15, 9–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Separation, anxiety and anger (Vol. 2). Hogarth. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky, W. (1996). Music performance anxiety reconceptualised: A critique of current research practice and findings. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 11(3), 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, J., & Berlin, L. J. (1994). The insecure/ambivalent pattern of attachment: Theory and research. Child Development, 65(4), 971–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davanloo, H. (1995). Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy: Spectrum of psychoneurotic disorders. International Journal of Short Term Psychotherapy, 10, 121–156. [Google Scholar]

- Davanloo, H. (1996). Management of tactical defenses in intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy, Part II: Spectrum of tactical defenses. International Journal of Short-Term Psychotherapy, 11(3), 153–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eielsen, M., Ulvenes, P. G., Melsom, L., Wampold, B. E., Røssberg, J. I., Myhre, F., Sørensen, Ø., Rasch, S. M., & Abbass, A. (2025). Development and psychometric evaluation of a screening instrument for cognitive perceptual disruption (Copeds) in psychotherapy patients. Psychotherapy Research, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ein-Dor, T., Mikulincer, M., Doron, G., & Shaver, P. R. (2010). The attachment paradox: How can so many of us (the insecure ones) have no adaptive advantages? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(2), 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezriel, H. (1952). Notes on psychoanalytic group therapy: II: Interpretation and research. Psychiatry, 15(2), 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, A. (2019). Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy (ISTDP) therapists’ experiences of staying with clients’ intense emotional experiencing: An interpretative phenomenological analysis [Doctoral dissertation, University of East London]. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P. (2015). The effectiveness of psychodynamic psychotherapies: An update. World Psychiatry, 14(2), 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederickson, J. J., Messina, I., & Grecucci, A. (2018). Dysregulated anxiety and dysregulating defenses: Toward an emotion regulation informed dynamic psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowinski, A. (2011). Reactive attachment disorder: An evolving entity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, M. I. M. (2005). The therapeutic relationship in short-term dynamic psychotherapy: A comparison of Davanloo and Sifneos [Doctoral dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology]. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, E. (2008). The adult attachment interview: Protocol, method of analysis, and empirical studies. In J. C. P. R. Shaver (Ed.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 552–598). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, T. (2019). The psychodynamics of performance anxiety: Psychoanalytic psychotherapy in the treatment of social phobia/social anxiety disorder. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 49(3), 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. (2010). Exploring in security. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hoviatdoost, P., Schweitzer, R. D., Bandarian, S., & Arthey, S. (2020). Mechanisms of change in intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy: Systematized review. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 73(3), 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, M. L. (2025). Seeing signal anxiety: Davanloo’s pathways of anxiety discharge. American Journal of Psychotherapy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julien, D., & O’Connor, K. P. (2017). Recasting psychodynamics into a behavioral framework: A review of the theory of psychopathology, treatment efficacy, and process of change of the affect phobia model. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 47(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor-Martynuska, J., & Kenny, D. T. (2018). Psychometric properties of the “Kenny-Music Performance Anxiety Inventory” modified for general performance anxiety. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 49(3), 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T. (2004). Music performance anxiety: Is it the music, the performance or the anxiety? Music Forum, 10(4), 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D. T. (2005a). Performance anxiety: Multiple phenotypes, one genotype? Introduction to the special edition on performance anxiety. International Journal of Stress Management, 12(4), 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T. (2005b). A systematic review of treatment for music performance anxiety. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 18(3), 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T. (2009). Negative emotions in music making: Performance anxiety. In P. Juslin, & J. Sloboda (Eds.), Handbook of music and emotion: Theory, research, applications. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D. T. (2011). The psychology of music performance anxiety. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D. T. (2016). Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (STPP) for a severely performance anxious musician: A case report. Journal of Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(3), 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T., & Ackermann, B. J. (2016). Optimizing physical and psychological health in performing musicians. In S. Hallam, I. Cross, & M. Thaut (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology (pp. 390–401). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T., Driscoll, T., & Ackermann, B. (2014). Psychological well-being in professional orchestral musicians in Australia: A descriptive population study. Psychology of music, 42(2), 210–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T., & Holmes, J. (2015). Exploring the attachment narrative of a professional musician with severe performance anxiety: A case report. Journal of Psychology and Psychotherapy, 5(4), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T., & Holmes, J. (2018). Attachment quality is associated with music performance anxiety in professional musicians: An exploratory narrative study. Polish psychological bulletin, 49(3), 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsner, J., Wilson, S. J., & Osborne, M. S. (2023). Music performance anxiety: The role of early parenting experiences and cognitive schemas. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1185296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohut, H. (2018). The search for the self (Vol. 4). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Le Doux, J. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. Simon and Shuster. [Google Scholar]

- Leichsenring, F., & Salzer, S. (2014). A unified protocol for the transdiagnostic psychodynamic treatment of anxiety disorders: An evidence-based approach. Psychotherapy, 51(2), 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letourneau, N., Watson, B., Duffett-Leger, L., Hegadoren, K., & Tryphonopoulos, P. (2011). Cortisol patterns of depressed mothers and their infants are related to maternal–infant interactive behaviours. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 29(5), 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons-Ruth, K., Zeanah, C. H., & Gleason, M. M. (2015). Commentary: Should we move away from an attachment framework for understanding disinhibited social engagement disorder (DSED)? A commentary on Zeanah and Gleason (2015). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(3), 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Moran, G., Pederson, D. R., & Benoit, D. (2006). Unresolved states of mind, anomalous parental behavior, and disorganized attachment: A review and meta-analysis of a transmission gap. Attachment & Human Development, 8(2), 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, M. (1995). Attachment: Overview and implications for clinical work. In S. Goldberg, R. Muir, & J. Kerr (Eds.), Attachment theory: Social, developmental and clinical perspectives (pp. 404–474). Analytic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Main, M., Hesse, E., & Kaplan, N. (2005). Predictability of attachment behaviour and representational processes. In K. E. Grossman, K. Grossman, & E. Waters (Eds.), Attachment from infancy to adulthood: Lessons from longitudinal studies (pp. 245–304). Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1/2), 66–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, D. H. (1979). Individual psychotherapy and the science of psychodynamics (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Maunder, R. G., Lancee, W. J., Nolan, R. P., Hunter, J. J., & Tannenbaum, D. W. (2006). The relationship of attachment insecurity to subjective stress and autonomic function during standardized acute stress in healthy adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60(3), 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menninger, K. (1958). Theory of psychoanalytic technique. Basic Books/Hachette Book Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2011). Attachment, anger, and aggression. In P. R. Shaver (Ed.), Human aggression and violence: Causes, manifestations, and consequences (pp. 241–257). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Molnos, A. (1984). The two triangles are four: A diagram to teach the process of dynamic brief psychotherapy. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 1(2), 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli-Pott, U., & Mertesacker, B. (2009). Affect expression in mother–infant interaction and subsequent attachment development. Infant Behavior and Development, 32(2), 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. WW Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Ravari, M. A. R., Vaziri, S., Sarafraz, M., & Rafiepoor, A. (2024). The impact of intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy (ISTDP) on psychological capacity, anxiety severity, and functional gastrointestinal disorders in psychosomatic patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. International Journal of Education and Cognitive Sciences, 5(2), 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonover, L. (2025). Attachments and strategies: Music performance anxiety, trauma, and mental health distress within music learning environments. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, P. R., Mikulincer, M., Lavy, S., & Cassidy, J. (2009). Understanding and altering hurt feelings: An attachment-theoretical perspective on the generation and regulation of emotions. In A. L. Vangelisti (Ed.), Feeling hurt in close relationships (pp. 92–119). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spangler, G., & Grossmann, K. E. (1993). Biobehavioural organization in securely and insecurely attached infants. Child Development, 64, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroufe, L. A., & Waters, E. (1977). Attachment as an organizational construct. Child Development, 48, 1184–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, D. J. (2007). Attachment in psychotherapy. Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann, A., Vogel, D., Voss, C., Nusseck, M., & Hoyer, J. (2020). The role of retrospectively perceived parenting style and adult attachment behaviour in music performance anxiety. Psychology of Music, 48(5), 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnicott, D. W. (1965). A clinical study of the effect of a failure of the average expectable environment on a child’s mental functioning. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 46, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kenny, D. Psychotherapeutic Treatment of Attachment Trauma in Musicians with Severe Music Performance Anxiety. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091270

Kenny D. Psychotherapeutic Treatment of Attachment Trauma in Musicians with Severe Music Performance Anxiety. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091270

Chicago/Turabian StyleKenny, Dianna. 2025. "Psychotherapeutic Treatment of Attachment Trauma in Musicians with Severe Music Performance Anxiety" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091270

APA StyleKenny, D. (2025). Psychotherapeutic Treatment of Attachment Trauma in Musicians with Severe Music Performance Anxiety. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091270