Racial Imposter Syndrome and Music Performance Anxiety: A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Aetiology of Music Performance Anxiety and Racial Imposter Syndrome

After eight years of teaching, I still get nervous being in front of a class. More specifically, I assume that students see me as a white woman, that this is the identity they place on me. As a result, I have been unsure of how to present myself in these spaces, whether it is okay to identify as not-white while experiencing white privilege, if I am taking up too much space outlining my identity in the one-shot classroom, and whether it benefits anyone but myself to make that identity clear.

1.2. Treatment of Music Performance Anxiety and Racial Imposter Syndrome

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Informed Consent

2.2. Case Formulation

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21

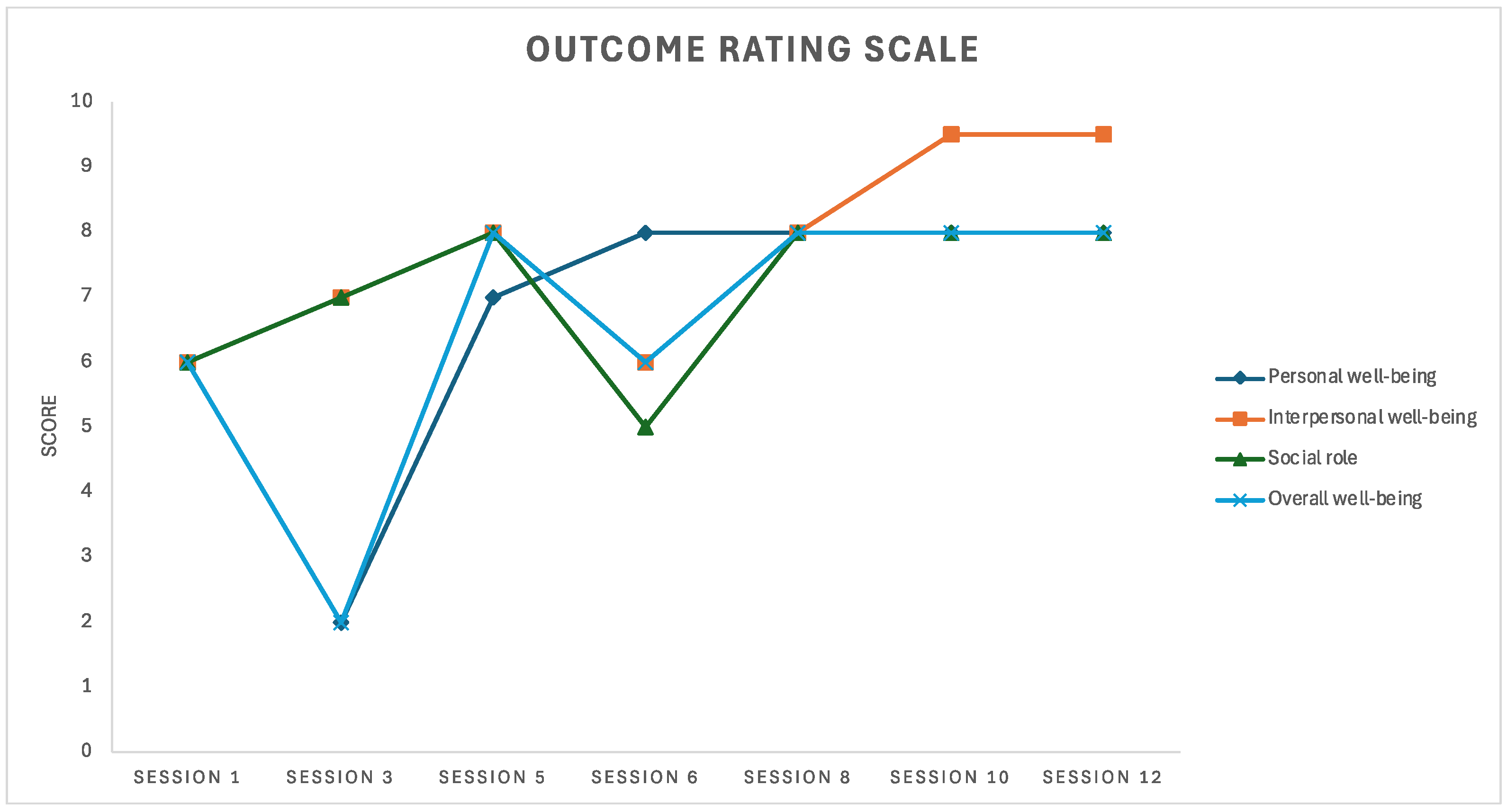

2.3.2. Outcome Rating Scale

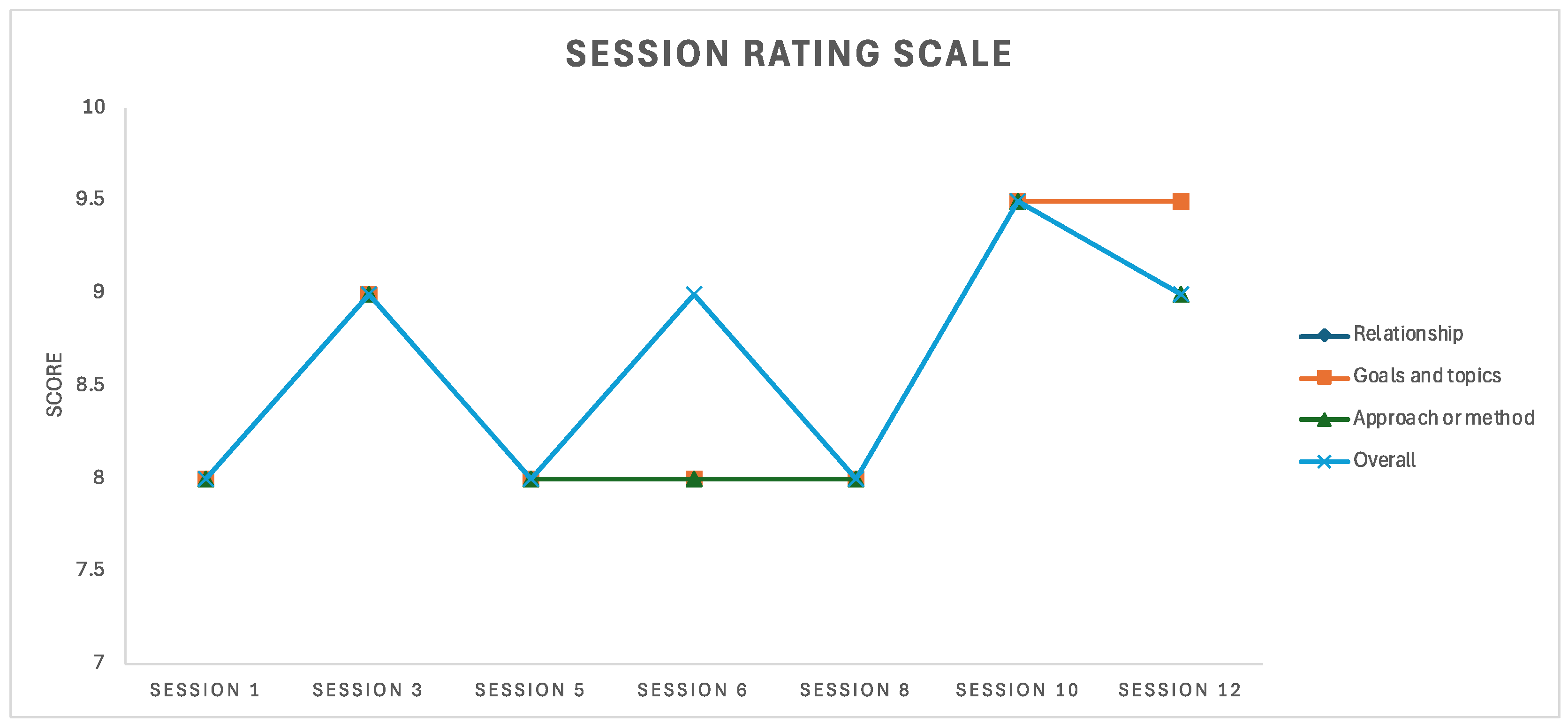

2.3.3. Session Rating Scale

2.4. Procedure

2.4.1. Attachment-Based Therapy

2.4.2. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

3. Results

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ainsworth, M. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44(4), 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, V., on behalf of COPE Council. (2016). Journals’ best practices for ensuring consent for publishing medical case reports: Guidance from COPE. COPE: Committee on Publication Ethics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D. H. (2000). Unraveling the mysteries of anxiety and its disorders from the perspective of emotion theory. American Psychologist, 55(11), 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartleet, B. L., Bennett, D., Bridgstock, R., Harrison, S., Draper, P., Tomlinson, V., & Ballico, C. (2020). Making music work: Sustainable portfolio careers for australian musicians. Australia Research Council Linkage Report. Queensland Conservatorium Research Centre, Griffith University. Available online: https://makingmusicworkcomau.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/mmw_full-report.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boyett, C. (2019). Music performance anxiety. MTNA e—Journal, 10(3), 2–21. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/music-performance-anxiety/docview/2188097483/se-2 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Bravata, D. M., Watts, S. A., Keefer, A. L., Madhusudhan, D. K., Taylor, K. T., Clark, D. M., Nelson, R. S., Cokley, K. O., & Hagg, H. K. (2020). Prevalence, Predictors, and Treatment of Impostor Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(4), 1252–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringhurst, D., Watson, C., Miller, S., & Duncan, B. (2006). The reliability and validity of the outcome rating scale: A replication study of a brief clinical measure. Journal of Brief Therapy, 5(1), 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). Ecological systems theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Annals of child development. Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues (pp. 187–249). Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, A. W. (2014). Get excited: Reappraising pre-performance anxiety as excitement. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143, 1144–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D. P., & Elliott, D. S. (2016). Attachment disturbances in adults: Treatment for comprehensive repair. W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D., Rodgers, Y. H., & Kapadia, K. (2008). Multicultural considerations for the application of attachment theory. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 62(4), 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, D. D. (1999). The feeling good handbook: The groundbreaking program with powerful new techniques and step-by-step exercises to overcome depression, conquer anxiety, and enjoy greater intimacy. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos, G. P., Mentis, A. A., & Efthimios, D. (2020). Focusing on the neuro-psycho-biological and evolutionary underpinnings of the imposter syndrome. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 15(3), 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L. K., Osborne, M. S., & Baranoff, J. A. (2020). Examining a group acceptance and commitment therapy intervention for music performance anxiety in student vocalists. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cokley, K. O., Bernard, D. L., Stone-Sabali, S., & Awad, G. H. (2024). Impostor phenomenon in racially/ethnically minoritized groups: Current knowledge and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 20(1), 407–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coşkun-Şentürk, G., & Çırakoğlu, O. C. (2018). How guilt/shame proneness and coping styles are related to music performance anxiety and stress symptoms by gender. Psychology of Music, 46(5), 682–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S. (2007). Racism as trauma: Some reflections on psychotherapeutic work with clients from the African-Caribbean Diaspora from an attachment-based perspective. In J. Schwartz, & K. White (Eds.), Attachment: New directions in psychotherapy and relational psychoanalysis (Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 179–199). Phoenix Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Donella, L. (2018). ‘Racial impostor syndrome’: Here are your stories. NPR Code Switch. Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2018/01/17/578386796/racial-impostor-syndrome-here-are-your-stories (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Duncan, B. L., Miller, S. D., Sparks, J. A., Claud, D. A., Reynolds, L. R., Brown, J., & Johnson, L. D. (2003). The session rating scale: Preliminary psychometric properties of a “working” alliance measure. Journal of Brief Therapy, 3(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- East Metropolitan Health Service, Government of Western Australia. (2020). Case reports. Available online: https://emhs.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/HSPs/EMHS/Documents/Research/EMHS-Case-Reports--Ethical-Considerations-v30-Oct-2020.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Fang, S., & Ding, D. (2023). The differences between acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and cognitive behavioral therapy: A three-level meta-analysis. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 28, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadsby, S., & Hohwy, J. (2024). Negative performance evaluation in the imposter phenomenon. Current Psychology, 43, 9300–9308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, A. J. A. A., Hildebrandt, H., Güsewell, A., Horsch, A., Nater, U. M., & Gomez, P. (2022). How audience and general music performance anxiety affect classical music students’ flow experience: A close look at its dimensions. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 959190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. (2009). ACT made simple: An easy-to-read primer on acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R. (2010). A quick look at your values. Available online: https://www.actmindfully.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Values_Checklist_-_Russ_Harris.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Harris, R. (2016). The complete set of client handouts and worksheets from ACT books by Russ Harris. Available online: https://thehappinesstrap.com/upimages/Complete_Worksheets_2014.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Harris, R., Murphy, M. G., & Rakes, S. (2019). The psychometric properties of the outcome rating scale used in practice: A narrative review. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 16(5), 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncos, D. G., & de Paiva e Pona, E. (2018). Acceptance and commitment therapy as a clinical anxiety treatment and performance enhancement program for musicians: Towards an evidence-based practice model within performance psychology. Music & Science, 1, 2059204317748807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncos, D. G., Heinrichs, G. A., Towle, P., Duffy, K., Grand, S. M., Morgan, M. C., Smith, J. D., & Kalkus, E. (2017). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for the treatment of music performance anxiety: A pilot study with student vocalists. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncos, D. G., & Markman, E. J. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of music performance anxiety: A single subject design with a university student. Psychology of Music, 44(5), 935–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T. (2009). The factor structure of the revised kenny music performance anxiety inventory. In International symposium on performance science (pp. 37–41). Association Européenne des Conservatoires. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D. T. (2011). The psychology of music performance anxiety. Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T. (2016). Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (STPP) for a severely performance anxious musician: A case report. Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy, 6(272), 1000272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T., Davis, P., & Oates, J. (2004). Music performance anxiety and occupational stress amongst opera chorus artists and their relationship with state and trait anxiety and perfectionism. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 18(6), 757–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T., & Holmes, J. (2015). Exploring the attachment narrative of a professional musician with severe performance anxiety: A case report. Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy, 5, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, C., Saville, P., Heiderscheit, A., & Himmerich, H. (2025). Therapeutic interventions for music performance anxiety: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsner, J., Wilson, S. J., & Osborne, M. S. (2023). Music performance anxiety: The role of early parenting experiences and cognitive schemas. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1185296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocker, N., & Mbenna, P. (2025). Inheriting racial privilege and oppression through proximity: Evidence from the everyday lives of mixed-race couples in Australia. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 115(5), 1125–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, S. (2022). Racial imposter syndrome, white presenting, and burnout in the one-shot classroom. College & Research Libraries, 83(5), 841–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Lee, E. H., & Moon, S. H. (2019). Systematic review of the measurement properties of the depression anxiety stress scales-21 by applying updated COSMIN methodology. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 28(9), 2325–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M. E., Herbert, J. D., & Forman, E. M. (2017). Acceptance and commitment therapy: A critical review to guide clinical decision making. In D. McKay, J. S. Abramowitz, & E. A. Storch (Eds.), Treatments for Psychological Problems and Syndromes (pp. 413–432). Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21, DASS-42) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K. K. L., Kleitman, S., & Abbott, M. J. (2019). Impostor phenomenon measurement scales: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S. D., Duncan, B. L., Brown, J., Sparks, J. A., & Claud, D. A. (2003). The outcome rating scale: A preliminary study on the reliability, validity and feasibility of a brief visual analog measure. Journal of Brief Therapy, 2, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, A., Bryan, A., Faber, N. S., Printz Pereira, D., Faber, S., Williams, M. T., & Skinta, M. D. (2023). A systematic review of inclusion of minoritized populations in randomized controlled trials of acceptance and commitment therapy. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 29, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M. G., Rakes, S., & Harris, R. M. (2020). The psychometric properties of the session rating scale: A narrative review. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 17(3), 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal, K. L., King, R., Sissoko, G., Floyd, N., & Hines, D. (2021). The legacies of systemic and internalized oppression: Experiences of microaggressions, imposter phenomenon, and stereotype threat on historically marginalized groups. New Ideas in Psychology, 63, 100895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholl, T. J., & Abbott, M. J. (2024). Debilitating performance anxiety in musicians and the performance specifier for social anxiety disorder: Should we be playing the same tune? Clinical Psychologist, 28(3), 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H., Winn, J. G., Li Verdugo, J., Bañada, R., Zachry, C. E., Chan, G., Okine, L., Park, J., Formigoni, M., & Leaune, E. (2024). Mental health outcomes of multiracial individuals: A systematic review between the years 2016 and 2022. Journal of Affective Disorders, 347, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, M. S., & Kenny, D. T. (2008). The role of sensitizing experiences in music performance anxiety in adolescent musicians. Psychology of Music, 36(4), 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, M. S., Munzel, B., & Greenaway, K. H. (2020). Emotion goals in music performance anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne. (n.d.). Research governance and ethics. Available online: https://www.rch.org.au/ethics/researcher-resources/Help_and_FAQs (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Salhany, A. (2022). Racial imposter syndrome makes you feel like your identity isn’t yours. Vice. Available online: https://www.vice.com/en/article/what-is-racial-imposter-syndrome/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Saulsman, L. M. (2025). Using metaphor to facilitate cognitive detachment in cognitive behaviour therapies. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 18, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D. J. (1999). The developing mind: Toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, W. L., & Ryan, C. (2023). Relationships between music performance anxiety and impostor phenomenon responses of graduate music performance students. Psychology of Music, 52(4), 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, A., & Holmes, J. (2019). Attachment and psychotherapy. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, J. A., Barbarin, O., & Cassidy, J. (2021). Working toward anti-racist perspectives in attachment theory, research, and practice. Attachment & Human Development, 24(3), 392–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajfel, H., Turner, J. C., Austin, W. G., & Worchel, S. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In M. J. Hatch, & M. Schultz (Eds.), Organizational identity: A reader (pp. 33–47). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Twitchell, A. J., Journault, A.-A., Singh, K. K., & Jamieson, J. P. (2025). A review of music performance anxiety in the lens of stress models. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1576391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, Y. (2021). Students’ recollections of parenting styles and impostor phenomenon: The mediating role of social anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences, 172, 110598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fraser, T. Racial Imposter Syndrome and Music Performance Anxiety: A Case Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081057

Fraser T. Racial Imposter Syndrome and Music Performance Anxiety: A Case Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081057

Chicago/Turabian StyleFraser, Trisnasari. 2025. "Racial Imposter Syndrome and Music Performance Anxiety: A Case Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081057

APA StyleFraser, T. (2025). Racial Imposter Syndrome and Music Performance Anxiety: A Case Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081057