Emotional and Subsequent Behavioral Responses After Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: A Meta-Analysis Based Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. UPB and Its Emotional Responses

2.1.1. UPB and the Positive Emotional Responses

2.1.2. UPB and the Negative Emotional Responses

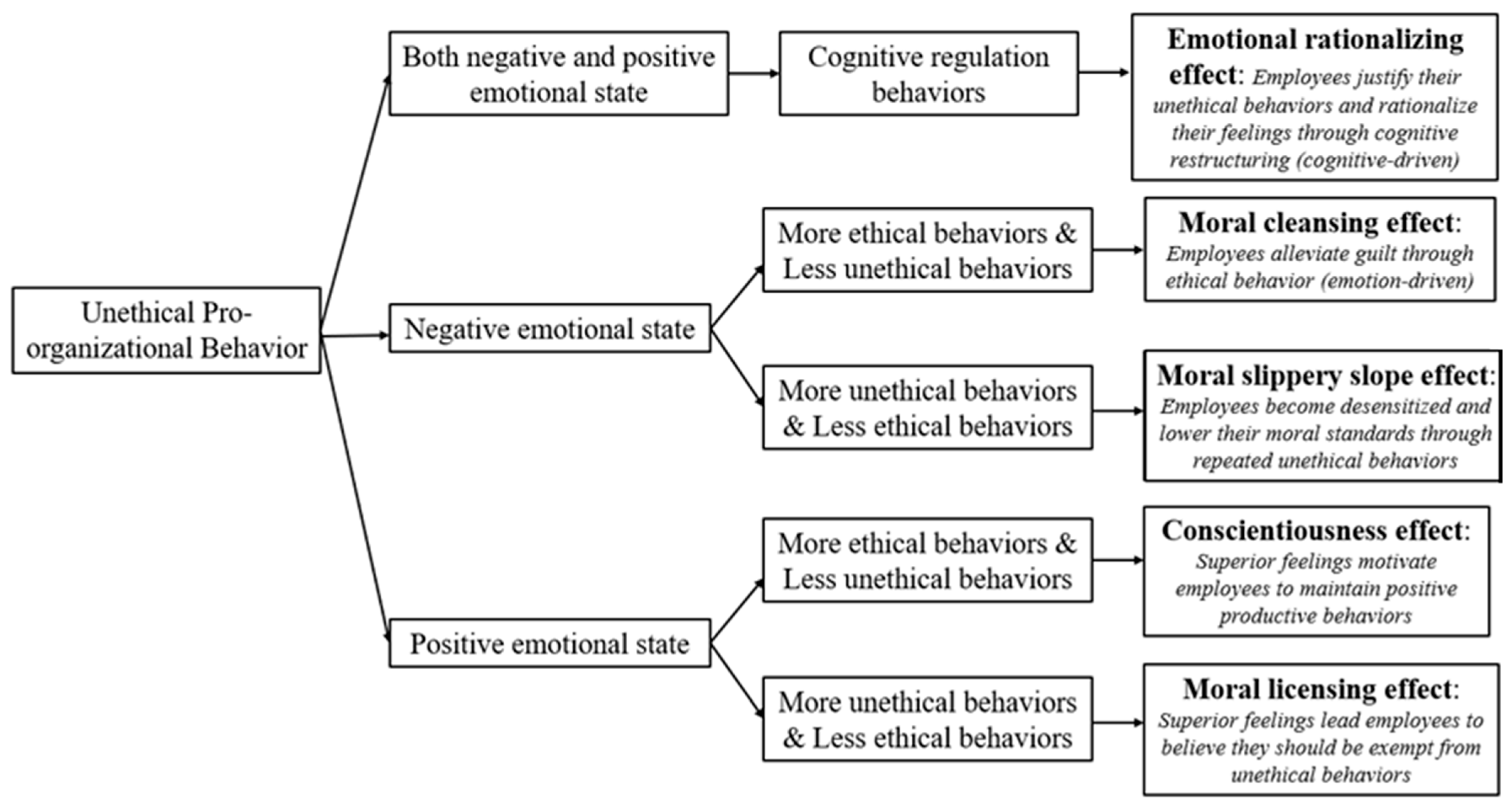

2.2. Emotional Responses of UPB and Subsequent Behaviors

2.2.1. Moral Cleansing Effect

2.2.2. Emotional Rationalizing Effect

2.2.3. Moral Slippery Slope Effect

2.2.4. Moral Licensing Effect

2.2.5. Conscientiousness Effect

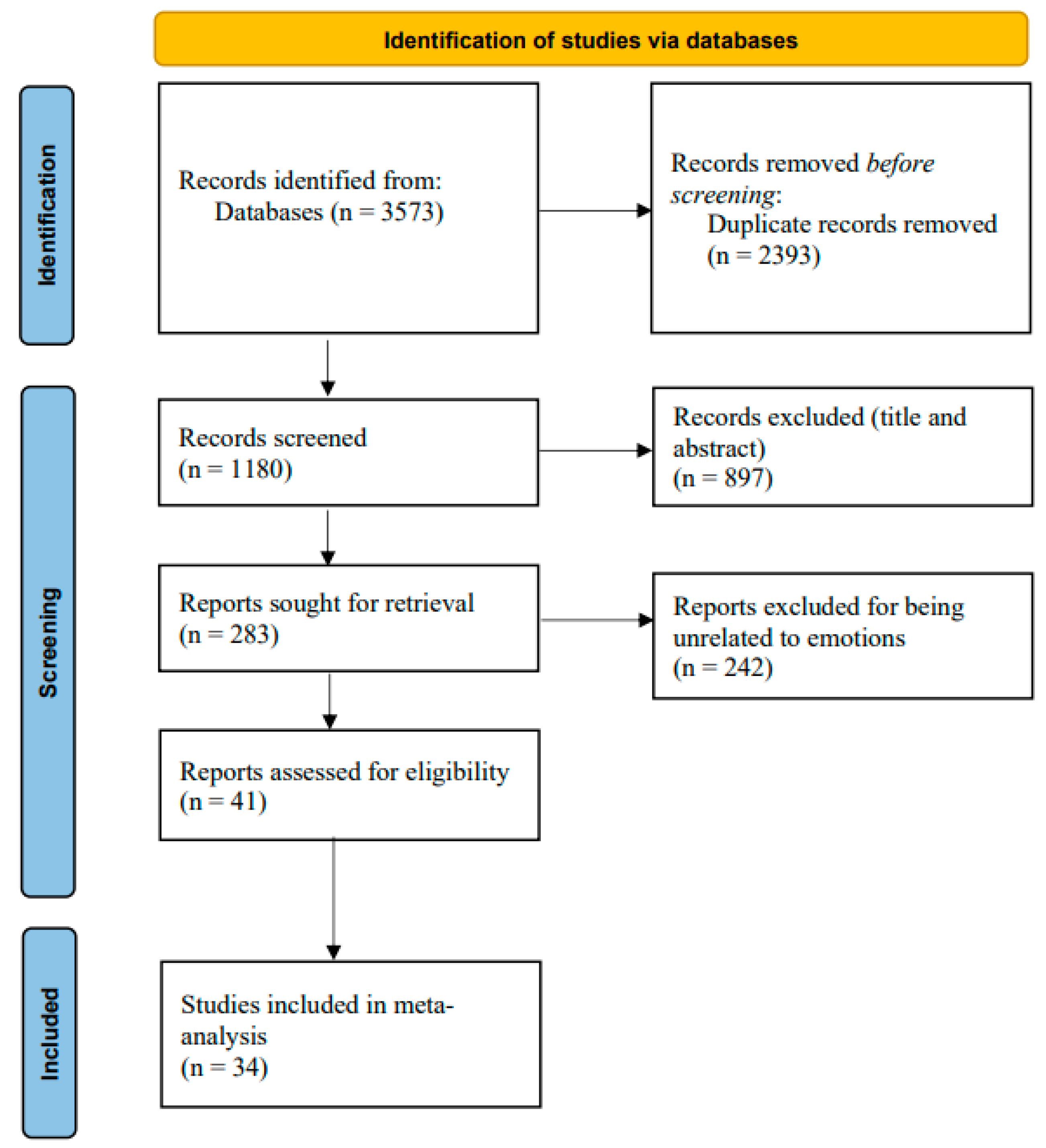

3. Methods

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.3. Data Extraction and Coding

3.4. Quality Assessment

3.5. Statistical Analysis Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Description of Studies

4.2. Heterogeneity Test

4.3. Publication Bias Analysis

4.4. Overall Effect Size Estimation

5. Discussion

5.1. Positive Emotions Elicited by UPB and Subsequent Behavioral Mechanisms

5.2. Negative Emotions Elicited by UPB and Subsequent Behavioral Mechanisms

5.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COR | Conservation of resources |

| EE | Emotional exhaustion |

| PE | Psychological entitlement |

| UPB | Unethical pro-organizational behavior |

References

- Azhar, S., Zhang, Z., & Simha, A. (2024). Leader unethical pro-organizational behavior: An implicit encouragement of unethical behavior and development of team unethical climate. Current Psychology, 43(28), 23597–23610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakbergenuly, I., Hoaglin, D. C., & Kulinskaya, E. (2019). Estimation in meta-analyses of mean difference and standardized mean difference. Statistics in Medicine, 39(2), 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakbergenuly, I., Hoaglin, D. C., & Kulinskaya, E. (2020). Estimation in meta-analyses of response ratios. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20(1), 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Effect sizes based on correlations. In Introduction to meta-analysis (pp. 41–43). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W. K., Bonacci, A. M., Shelton, J., Exline, J. J., & Bushman, B. J. (2004). Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 83(1), 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C. S., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2009). Anger is an approach-related affect: Evidence and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., & Zhang, S. (2024). Employees’ unethical pro-organizational behavior and subsequent internal whistle-blowing. Chinese Management Studies, 19(1), 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Chen, C. C., & Schminke, M. (2023). Feeling guilty and entitled: Paradoxical consequences of unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 183(3), 865–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Chen, C. C., & Sheldon, O. J. (2016). Relaxing moral reasoning to win: How organizational identification relates to unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(8), 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi-Ho, C. (2015). An exploration of the relationships between job motivation, collective benefit, target awareness, and organizational citizenship behavior in Chinese culture. Comprehensive Psychology, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadaboyev, S. M. U., Choi, S., & Paek, S. (2022). Why do good soldiers in good organizations behave wrongly? The vicarious licensing effect of perceived corporate social responsibility. Baltic Journal of Management, 17(5), 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennerlein, T., & Kirkman, B. L. (2022). The hidden dark side of empowering leadership: The moderating role of hindrance stressors in explaining when empowering employees can promote moral disengagement and unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(12), 2220–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwan, K., Altman, D. G., Arnaiz, J. A., Bloom, J., Chan, A., Cronin, E., Decullier, E., Easterbrook, P. J., Von Elm, E., Gamble, C., Ghersi, D., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Simes, J., & Williamson, P. R. (2008). Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS ONE, 3(8), e3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farh, J.-L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support-employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. The Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A. S., Podsakoff, N. P., Beal, D. J., Scott, B. A., Sonnentag, S., Trougakos, J. P., & Butts, M. M. (2019). Experience sampling methods: A discussion of critical trends and considerations for scholarly advancement. Organizational Research Methods, 22(4), 969–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z. H., Zhang, H., Xu, Y., & Chen, J. Y. (2023). Perceived leader dependence and unethical pro-organizational behavior—A moderated chain mediation model. Research on Economics and Management, 44(4), 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, K. A., Resick, C. J., Margolis, J. A., Shao, P., Hargis, M. B., & Kiker, J. D. (2020). Egoistic norms, organizational identification, and the perceived ethicality of unethical pro-organizational behavior: A moral maturation perspective. Human Relations, 73(9), 1249–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, M., & Low, K. (2014). Public integrity, private hypocrisy, and the moral licensing effect. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(3), 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupe, D. W., & Nitschke, J. B. (2013). Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: An integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 14(7), 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X., Sui, Y., & Yan, Q. (2023). Unethical pro-organizational behavior and task performance: A moderated mediation model of depression and self-reflection. Ethics & Behavior, 34(8), 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical Research Edition), 327(7414), 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H., Hsu, H., Kao, K., & Wang, C. (2020). Ethical leadership and employee unethical pro-organizational behavior: A moderated mediation model of moral disengagement and coworker ethical behavior. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 41(6), 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D. M., He, L. F., & Chen, M. (2021). Leader’s unethical pro-organizational behavior and employee’s emotional exhaustion: A cognitive appraisal of emotions perspective. Human Resources Development of China, 38(10), 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., Dong, Y., Chen, X., Liu, Y., Ma, D., Liu, X., Zheng, R., Mao, X., Chen, T., & He, W. (2015). Prevalence of suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 61, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IntHout, J., Ioannidis, J. P., & Borm, G. F. (2014). The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M., & Bashir, S. (2020). The dark side of organizational identification: A multi-study investigation of negative outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 572478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W., Liang, B., & Wang, L. (2023). The Double-Edged Sword Effect of Unethical pro-organizational behavior: The relationship between unethical pro-organizational behavior, organizational citizenship behavior, and work effort. Journal of Business Ethics, 183(4), 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelebek, E. E., & Alniacik, E. (2022). Effects of leader-member exchange, organizational identification and leadership communication on unethical Pro-Organizational behavior: A study on bank employees in Turkey. Sustainability, 14(3), 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, K. F., Sarfraz, M., & Khalil, M. (2023). Doing good for organization but feeling bad: When and how narcissistic employees get prone to shame and guilt. Future Business Journal, 9(1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M., Xin, J., Xu, W., Li, H., & Xu, D. (2022). The moral licensing effect between work effort and unethical pro-organizational behavior: The moderating influence of Confucian value. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 39(2), 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E. R., & Kacmar, K. M. (2017). Exploring the impact of job insecurity on employees’ unethical behavior. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(1), 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist, 46(8), 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A., Schwarz, G., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2019). Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 154(1), 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. C., Wang, Z., Zhu, Z. B., & Zhan, X. J. (2018). Performance pressure and unethical pro-organizational behavior: Based on cognitive appraisal theory of emotion. Chinese Journal of Management, 15(3), 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, H., Huai, M., Farh, J., Huang, J., Lee, C., & Chao, M. M. (2020). Leader unethical pro-organizational behavior and employee unethical conduct: Social learning of moral disengagement as a behavioral principle. Journal of Management, 48(2), 350–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z., Yam, K. C., Johnson, R. E., Liu, W., & Song, Z. (2018). Cleansing my abuse: A reparative response model of perpetrating abusive supervisor behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(9), 1039–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Z., Yam, K. C., Lee, H. W., Johnson, R. E., & Tang, P. M. (2023). Cleansing or licensing? Corporate social responsibility reconciles the competing effects of unethical Pro-Organizational behavior on moral Self-Regulation. Journal of Management, 50(5), 1643–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. J., Liu, L. Y., Syed, Z. A., & Zou, L. M. (in press). Using the process dissociation paradigm to independently measure the ethical and organizational dimensions of unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Business Ethics. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. (2024). How does temporal leadership affect unethical pro-organizational behavior? The roles of emotional exhaustion and job complexity. Kybernetes. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Zhu, Y., Chen, S., Zhang, Y., & Qin, F. (2021). Moral decline in the workplace: Unethical pro-organizational behavior, psychological entitlement, and leader gratitude expression. Ethics & Behavior, 32(2), 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. L., Lu, J. G., Zhang, H., & Cai, Y. (2021). Helping the organization but hurting yourself: How employees’ unethical pro-organizational behavior predicts work-to-life conflict. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 167, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., & Greenbaum, R. L. (2010). Examining the link between ethical leadership and employee misconduct: The mediating role of ethical climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(S1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q., Eva, N., Newman, A., Nielsen, I., & Herbert, K. (2019). Ethical leadership and unethical pro-organisational behaviour: The mediating mechanism of reflective moral attentiveness. Applied Psychology, 69(3), 834–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M., Ghosh, K., & Sharma, D. (2022). Unethical pro-organizational behavior: A systematic review and future research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics, 179(1), 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S., Lupoli, M. J., Newman, A., & Umphress, E. E. (2022). Good intentions, bad behavior: A review and synthesis of the literature on unethical prosocial behavior (UPB) at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 44(2), 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, B., & Miller, D. T. (2001). Moral credentials and the expression of prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(1), 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, S., Bouckenooghe, D., Syed, F., Khan, A. K., & Qazi, S. (2020). The malevolent side of organizational identification: Unraveling the impact of psychological entitlement and manipulative personality on unethical work behaviors. Journal of Business and Psychology, 35(3), 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, S., Talebzadeh, N., Ozturen, A., & Altinay, L. (2023). Investigating a sequential mediation effect between unethical leadership and unethical pro-family behavior: Testing moral awareness as a moderator. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 33(3), 308–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research Edition), 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, H., Björklund, F., & Bäckström, M. (2025). How social desirability influences the relationship between measures of personality and key constructs in positive psychology. Journal of Happiness Studies, 26(3), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J., & Gao, X. X. (2011). Moral emotions: The moral behavior’s intermediary mediation. Advances in Psychological Science, 19(8), 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, R. W., Noftle, E. E., & Tracy, J. L. (2007). Assessing self conscious emotions: A review of self-report and nonverbal measures. In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 443–467). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rostom, A., Dubé, C., Cranney, A., Saloojee, N., Sy, R., Garritty, C., Sampson, M., Zhang, L., Yazdi, F., Mamaladze, V., Pan, I., McNeil, J., Moher, D., Mack, D., & Patel, D. (2004). Celiac disease (evidence reports/technology assessments, No. 104., Appendix D. Quality assessment forms). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK35156/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Rothstein, H. R., Sutton, A. J., & Borenstein, M. (2005). Publication bias in meta-analysis. In H. R. Rothstei, A. J. Sutton, & M. Borenstein (Eds.), Publication bias in meta-analysis: Prevention, assessment & adjustments (pp. 1–7). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W. (2011). A review of the research on moral psychological licensing. Advances in Psychological Science, 19(8), 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y., Hur, W., Kang, D. Y., & Shin, G. (2024). Why pro-organizational unethical behavior contributes to helping and innovative behaviors: The mediating roles of psychological entitlement and perceived insider status. Current Psychology, 43(30), 25135–25152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, L. M., Rees, R., & Berry, C. M. (2023). The role of self-interest in unethical pro-organizational behavior: A nomological network meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(3), 362–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistiawan, J., Sumarsono, J. J. P., Lin, P., & Dwikesumasari, P. R. (2024). Navigating the thin line: Can acts of good lead to defiance at work? Exploring the intricacies of OCB and CWB dynamics. Public Integrity, 27(5), 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C., Chen, Y., Wei, W., & Newman, D. A. (2024). Under pressure: LMX drives employee unethical pro-organizational behavior via threat appraisals. Journal of Business Ethics, 195(4), 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P. M., Yam, K. C., & Koopman, J. (2020). Feeling proud but guilty? Unpacking the paradoxical nature of unethical pro-organizational behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 160, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P. M., Yam, K. C., Koopman, J., & Ilies, R. (2021). Admired and disgusted? Third parties’ paradoxical emotional reactions and behavioral consequences towards others’ unethical pro-organizational behavior. Personnel Psychology, 75(1), 33–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J. P., Mashek, D., & Stuewig, J. (2007). Working at the social-clinical-community-criminology interface: The GMU Inmate Study. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2006). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 345–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2004). Putting the self into self-conscious emotions: A theoretical model. Psychological Inquiry, 15(2), 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2007). The psychological structure of pride: A tale of two facets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 506–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism & collectivism. Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Umphress, E. E., & Bingham, J. B. (2011). When employees do bad things for good reasons: Examining unethical Pro-Organizational behaviors. Organization Science, 22(3), 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphress, E. E., Bingham, J. B., & Mitchell, M. S. (2010). Unethical behavior in the name of the company: The moderating effect of organizational identification and positive reciprocity beliefs on unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(4), 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1), 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Y., Tian, H., & Xing, H. W. (2018). Research on internal auditors’ unethical pro-organizational behavior: From the perspective of dual identification. Journal of Management Science, 31(4), 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Wang, G., Liu, G., & Zhou, Q. (2022). Compulsory unethical pro-organisational behaviour and employees’ in-role performance: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 32(6), 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., Long, L., Zhang, Y., & He, W. (2019). A social exchange perspective of employee–organization relationships and employee unethical pro-organizational behavior: The moderating role of individual moral identity. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(2), 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Xiao, S., & Ren, R. (2022). A moral cleansing process: How and when does unethical pro-organizational behavior increase prohibitive and promotive voice. Journal of Business Ethics, 176(1), 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, D. T., Ordóñez, L. D., Snyder, D. G., & Christian, M. S. (2015). The slippery slope: How small ethical transgressions pave the way for larger future transgressions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P., Chen, C., Chen, S., & Cao, Y. (2020). The Two-Sided Effect of leader unethical pro-organizational behaviors on subordinates’ behaviors: A mediated moderation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 572455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, C., & Zhong, C. (2015). Moral cleansing. Current Opinion in Psychology, 6, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, R., Chan, A., & Linstead, S. (2004). Theorizing Chinese employment relations comparatively: Exchange, reciprocity and the moral economy. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 21(3), 365–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F., Lu, P., Wang, L., & Bao, J. (2023). Investigating the moral compensatory effect of unethical pro-organizational behavior on ethical voice. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1159101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., & Wang, J. (2020). Influence of challenge–hindrance stressors on unethical pro-organizational behavior: Mediating role of emotions. Sustainability, 12(18), 7576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., Wen, T., & Wang, J. (2022). How does job insecurity cause unethical pro-organizational behavior? The mediating role of impression management motivation and the moderating role of organizational identification. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 941650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Yaacob, Z., & Cao, D. (2024). Casting light on the dark side: Unveiling the dual-edged effect of unethical pro-organizational behavior in ethical climate. Current Psychology, 43(16), 14448–14469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., & Lin, Y. (2024). Job demands and employees’ unethical pro-organizational behaviors: Emotional exhaustion as a mediator. Social Behavior and Personality an International Journal, 52(7), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N., Lin, C., Liao, Z., & Xue, M. (2022). When moral tension begets cognitive dissonance: An investigation of responses to unethical pro-organizational behavior and the contingent effect of construal level. Journal of Business Ethics, 180(1), 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z., Luo, J., Fu, N., Zhang, X., & Wan, Q. (2022). Rational counterattack: The impact of workplace bullying on unethical pro-organizational and pro-family behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 181(3), 661–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, D. W., Wan, W. P., & Xu, Y. (2019). Alternative governance and corporate financial fraud in transition economies: Evidence from China. Journal of Management, 45(7), 2685–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K., Wang, D., Huang, W., Li, Z., & Zheng, X. (2021). Role of moral judgment in peers’ vicarious learning from employees’ unethical pro-organizational behavior. Ethics & Behavior, 32(3), 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Liu, X. L., Cai, Y., & Sun, X. (2023). Paved with good intentions: Self-regulation breakdown after altruistic ethical transgression. Journal of Business Ethics, 186(2), 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Du, S. (2023). Moral cleansing or moral licensing? A study of unethical pro-organizational behavior’s differentiating Effects. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 40(3), 1075–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., He, B., & Sun, X. (2018). The contagion of unethical pro-organizational behavior: From leaders to followers. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. J., Sun, Y. D., & Li, Y. X. (2022). Demand paying back or seek paying forward: The influence of job insecurity on unethical behavior. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 30(4), 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. J., Zhao, J., & Liu, Z. Q. (2020). Research on the self-interested risk of unethical pro-organizational behavior and its mechanisms. Chinese Journal of Management, 17(11), 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M., & Qu, S. (2022). Research on the consequences of employees’ unethical pro-organizational behavior: The moderating role of moral identity. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1068606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M., Qu, S., Tian, G., Mi, Y., & Yan, R. (2024). Research on the moral slippery slope risk of unethical pro-organizational behavior and its mechanism: A moderated mediation model. Current Psychology, 43(19), 17131–17145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C., Ku, G., Lount, R. B., & Murnighan, J. K. (2010). Compensatory ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 92(3), 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pathway | Type | k | N | Q | df (Q) | T2 | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPB and Emotional responses | pride | 7 | 69,825 | 78.593 *** | 6 | 0.017 | 94.747 |

| guilt | 17 | 72,232 | 281.669 *** | 16 | 0.062 | 97.622 | |

| shame | 7 | 68,765 | 391.841 *** | 6 | 0.041 | 96.632 | |

| anxiety | 8 | 3308 | 38.323 *** | 7 | 0.010 | 80.565 | |

| emotional exhaustion | 5 | 1271 | 212.452 *** | 4 | 0.198 | 97.975 | |

| psychological entitlement | 22 | 7531 | 241.007 *** | 21 | 0.037 | 92.559 | |

| Emotional responses and Behaviors | moral licensing | 18 | 7209 | 61.128 *** | 17 | 0.007 | 73.212 |

| moral slippery slope | 13 | 71,896 | 320.632 *** | 12 | 0.015 | 92.784 | |

| moral cleansing effect | 10 | 70,119 | 206.279 *** | 9 | 0.009 | 89.146 | |

| conscientiousness effect | 12 | 71,858 | 570.211 *** | 11 | 0.037 | 97.114 | |

| emotional rationalizing effect | 11 | 3795 | 75.413 *** | 10 | 0.018 | 87.191 |

| Pathway | Type | k | N | Fail-Safe N | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPB and Emotional responses | pride | 7 | 69,825 | 517.145 | <0.001 |

| guilt | 17 | 72,232 | 459.841 | <0.001 | |

| shame | 7 | 68,765 | 390.374 | <0.001 | |

| anxiety | 8 | 3308 | 1220.234 | <0.001 | |

| emotional exhaustion | 5 | 1271 | 4.068 | 0.652 | |

| psychological entitlement | 22 | 7531 | 1337.921 | <0.001 | |

| Emotional responses and Behaviors | moral licensing | 18 | 7209 | 2048.288 | <0.001 |

| moral slippery slope | 13 | 71,896 | 817.409 | <0.001 | |

| moral cleansing | 10 | 70,119 | 1537.556 | <0.001 | |

| conscientiousness effect | 12 | 71,858 | 673.728 | <0.001 | |

| emotional rationalizing effect | 11 | 3795 | 1214.929 | <0.001 |

| Pathway | Type | Estimate | SE | Z | ES(r) | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| UPB and Emotional responses | pride | 0.268 | 0.053 | 5.085 *** | 0.261 | 0.163 | 0.355 |

| guilt | 0.297 | 0.062 | 4.795 *** | 0.288 | 0.174 | 0.395 | |

| shame | 0.353 | 0.080 | 4.418 *** | 0.339 | 0.194 | 0.469 | |

| anxiety | 0.315 | 0.040 | 7.811 *** | 0.305 | 0.232 | 0.375 | |

| emotional exhaustion | −0.091 | 0.202 | −0.451 | −0.091 | −0.451 | 0.295 | |

| psychological entitlement | 0.353 | 0.043 | 8.179 *** | 0.339 | 0.262 | 0.411 | |

| Emotional responses and Behaviors | moral licensing | 0.241 | 0.024 | 10.120 *** | 0.237 | 0.192 | 0.280 |

| moral slippery slope | 0.237 | 0.037 | 6.393 *** | 0.233 | 0.163 | 0.300 | |

| moral cleansing | 0.304 | 0.035 | 8.768 *** | 0.295 | 0.232 | 0.356 | |

| conscientiousness effect | 0.332 | 0.057 | 5.804 *** | 0.321 | 0.217 | 0.418 | |

| emotional rationalizing effect | 0.340 | 0.044 | 7.794 *** | 0.328 | 0.249 | 0.402 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zou, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C. Emotional and Subsequent Behavioral Responses After Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: A Meta-Analysis Based Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091266

Zou L, Wang Y, Liu C. Emotional and Subsequent Behavioral Responses After Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: A Meta-Analysis Based Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091266

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Lemei, Yixiang Wang, and Chuanjun Liu. 2025. "Emotional and Subsequent Behavioral Responses After Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: A Meta-Analysis Based Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091266

APA StyleZou, L., Wang, Y., & Liu, C. (2025). Emotional and Subsequent Behavioral Responses After Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: A Meta-Analysis Based Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091266