Moderating Effects of Telework Intensity on the Relationship Between Ethical Climate, Affective Commitment and Burnout in the Colombian Electricity Sector Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Ethical Leadership and Affective Commitment

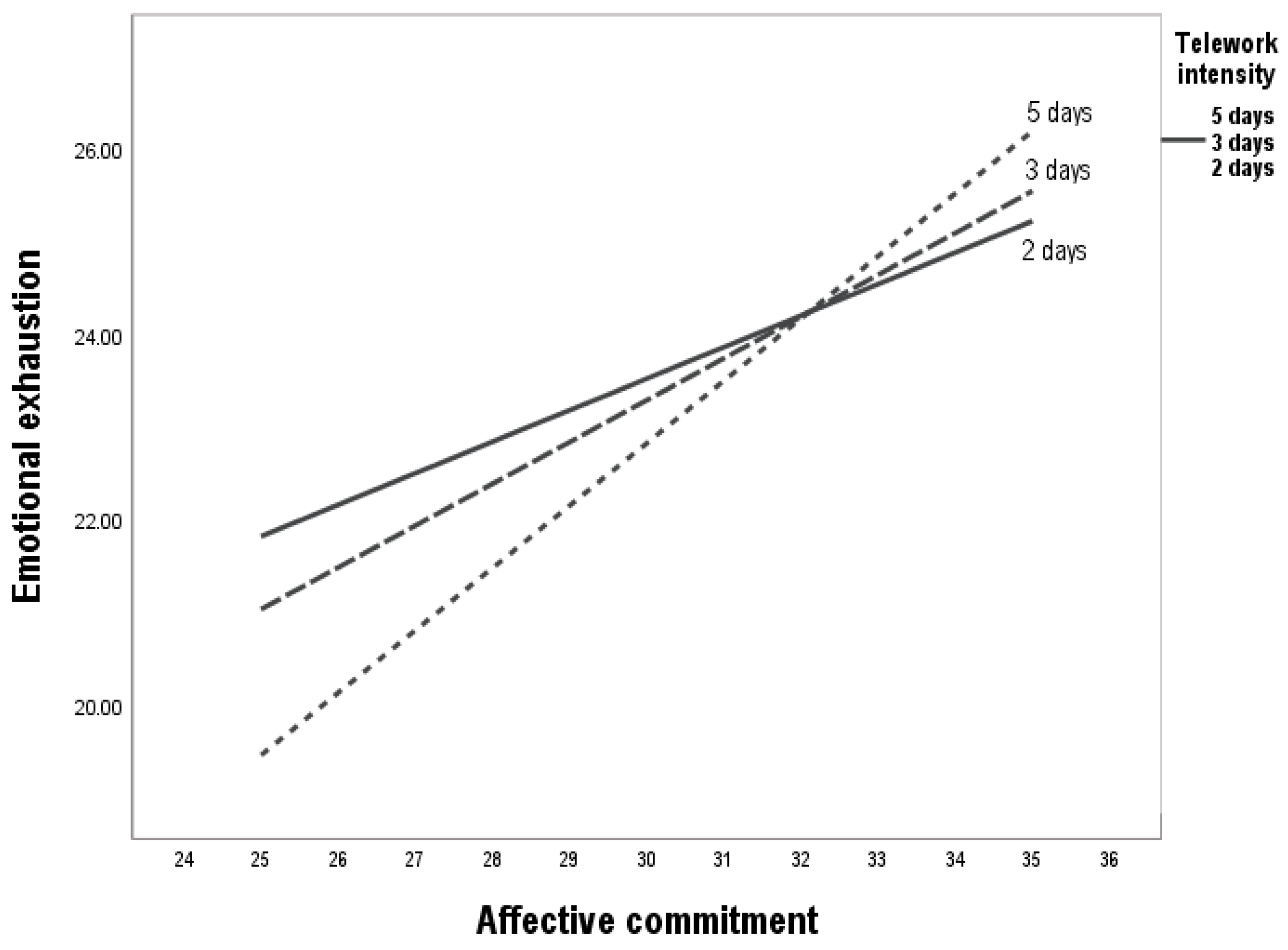

2.2. Affective Commitment and Emotional Exhaustion Under Telework Intensity

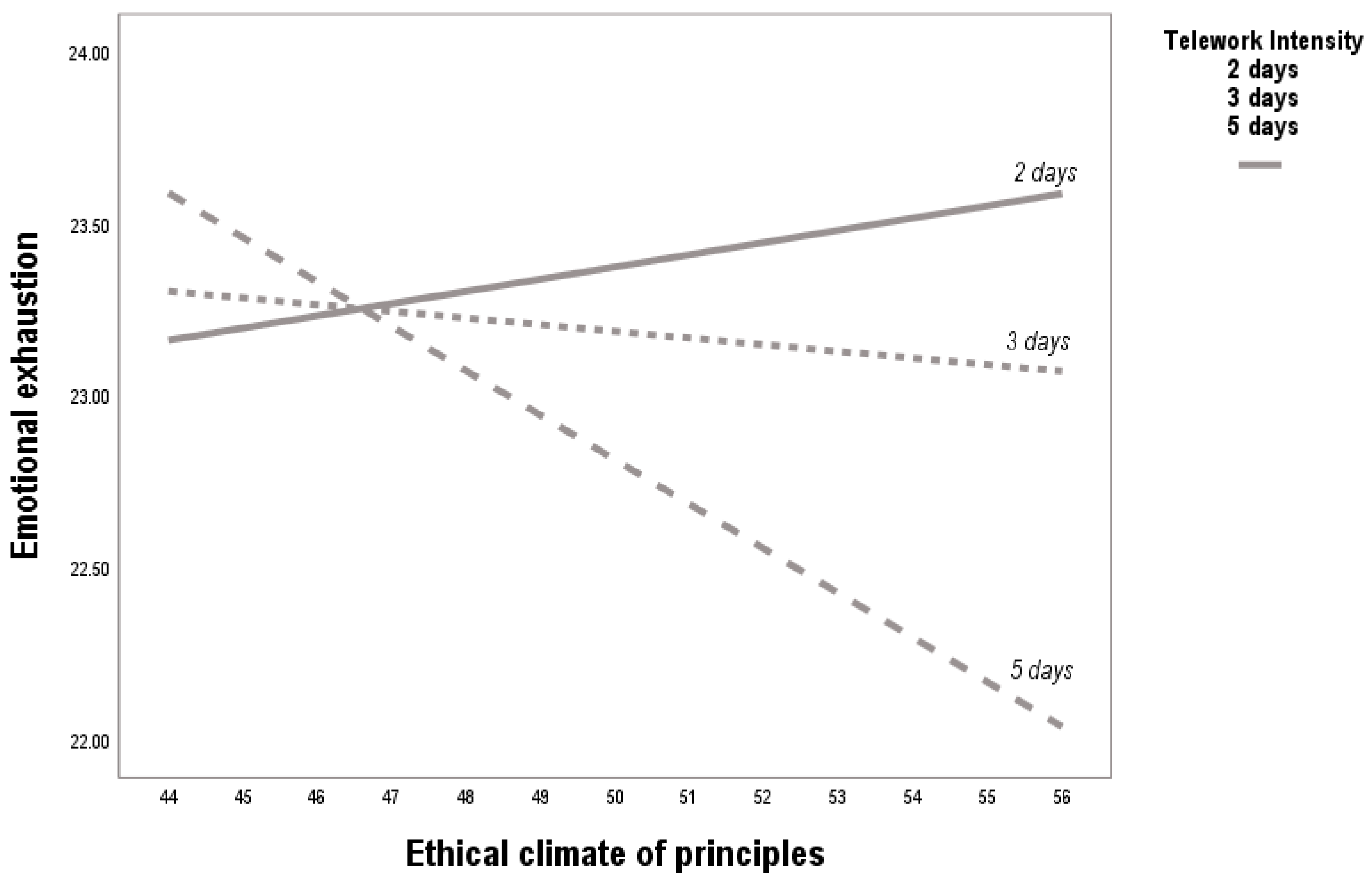

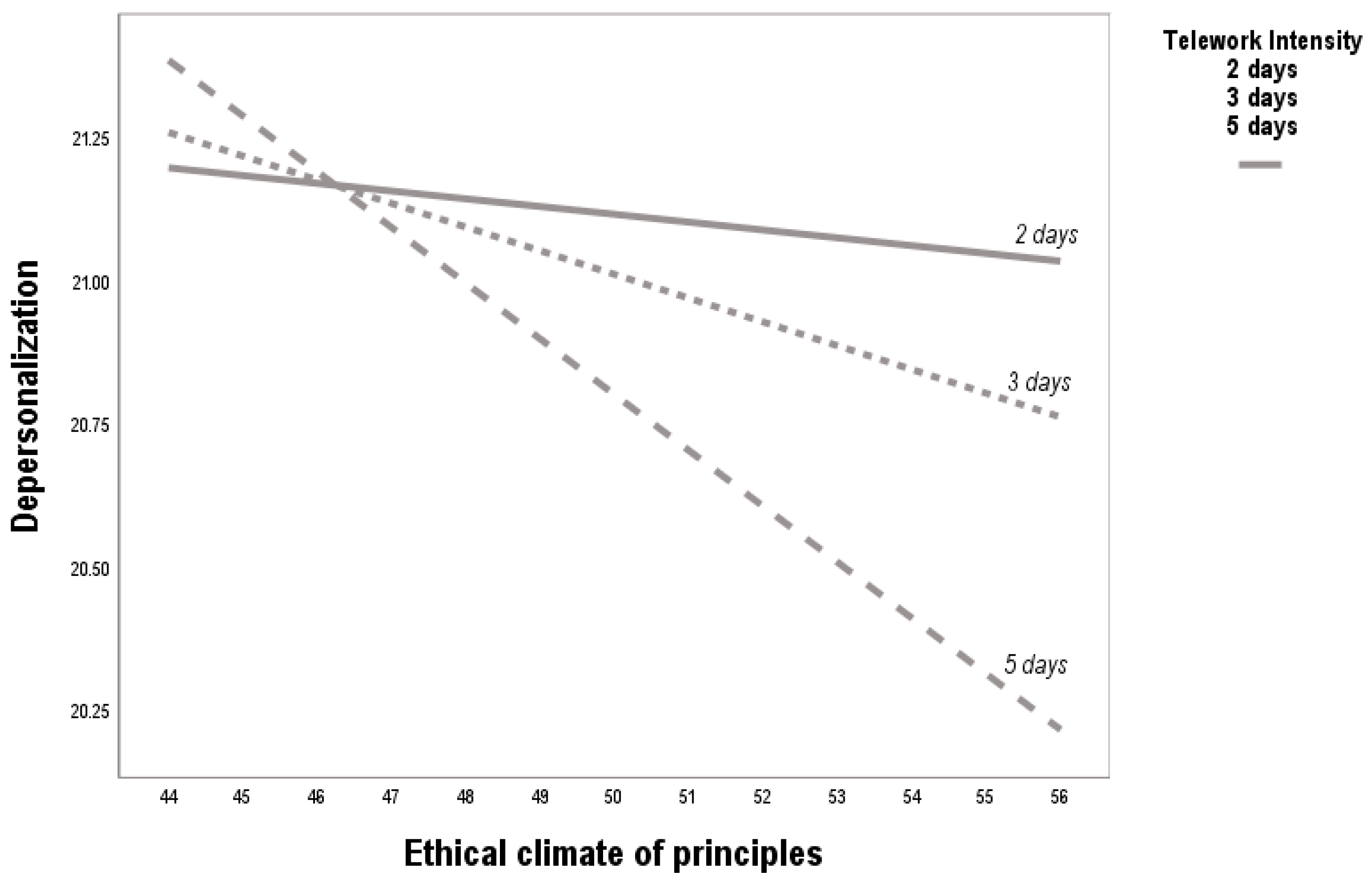

2.3. Principle-Based Ethical Climate, Emotional Exhaustion, and Depersonalization Under Telework Intensity

2.4. Conceptual Model: Ethical Leadership, Ethical Climate of Principles, Affective Commitment and Burnout: Moderated by Telework Intensity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Sampling Strategy

3.2. Data Collection Procedure

3.3. Measures

3.4. Ethical Considerations

3.5. Analytical Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Ethical Leadership and Affective Commitment

4.2. Affective Commitment and Emotional Exhaustion

4.3. Ethical Climate and Emotional Exhaustion

4.4. Ethical Climate and Depersonalization

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, T. D., Golden, T. D., & Shockley, K. M. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(2), 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, M., Qing, M., Hwang, J., & Shi, H. (2019). Ethical leadership, affective commitment, work engagement, and creativity: Testing a multiple mediation approach. Sustainability, 11(16), 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabay, G., Çangarli, B. G., & Penbek, Ş. (2015). Impact of ethical climate on moral distress revisited: Multidimensional view. Nursing Ethics, 22(1), 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2023). Job demands–resources theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, I., Rossi, M. F., Melcore, G., Perrotta, A., Santoro, P. E., Gualano, M. R., & Moscato, U. (2023). Workplace ethical climate and workers’ burnout: A systematic review. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 20(5), 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraoui, K., Bensemmane, S., Ohana, M., & Russo, M. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and employees’ affective commitment. Management Decision, 57(1), 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. J. Lonner, & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research (pp. 137–164). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, S.-T., Yirsa, J.-P., & Elisenda, T.-P. (2025). Ethical climate, intrinsic motivation, and affective commitment: The impact of depersonalization. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(4), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H., & van der Lippe, T. (2020). Flexible working, work–life balance, and gender equality: Introduction. Social Indicators Research, 151(2), 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K. S., Cheshire, C., Rice, E. R., & Nakagawa, S. (2013). Social exchange theory. In Handbook of social psychology (pp. 61–88). Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirani, K. M., Abadi, M., Alizadeh, A., Barhate, B., Garza, R. C., Gunasekara, N., Ibrahim, G., & Majzun, Z. (2020). Leadership competencies and the essential role of human resource development in times of crisis: A response to COVID-19 pandemic. Human Resource Development International, 23(4), 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, R. S., & Harrison, D. A. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A., Sengupta, S., Panda, M., Hati, L., Prikshat, V., Patel, P., & Mohyuddin, S. (2024). Teleworking: Role of psychological well-being and technostress in the relationship between trust in management and employee performance. International Journal of Manpower, 45(1), 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Simon, L. S., & Judge, T. A. (2016). A head start or a step behind? Understanding how dispositional and motivational resources influence emotional exhaustion. Journal of Management, 42(3), 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., So, K. K. F., & Wirtz, J. (2022). Service robots: Applying social exchange theory to better understand human–robot interactions. Tourism Management, 92(1), 104537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, K. M., Narayanan, J., Anseel, F., Antonakis, J., Ashford, S. P., Bakker, A. B., Bamberger, P., Bapuji, H., Bhave, D. P., Choi, V. K., Creary, S. J., Demerouti, E., Flynn, F. J., Gelfand, M. J., Greer, L. L., Johns, G., Kesebir, S., Klein, P. G., Lee, S. Y., … Vugt, M. V. (2021). COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. American Psychologist, 76(1), 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazauskaite-Zabielske, J., Ziedelis, A., & Urbanaviciute, I. (2022). When working from home might come at a cost: The relationship between family boundary permeability, overwork climate and exhaustion. Baltic Journal of Management, 17(5), 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazauskaitė-Zabielskė, J., Urbanavičiūtė, I., & Žiedelis, A. (2023). Pressed to overwork to exhaustion? The role of psychological detachment and exhaustion in the context of teleworking. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 44(3), 875–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesener, T., Gusy, B., & Wolter, C. (2019). The job demands-resources model: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work & Stress, 33(1), 76–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K. D., & Cullen, J. B. (2006). Continuities and extensions of ethical climate theory: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 69(2), 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercurio, Z. A. (2015). Affective commitment as a core essence of organizational commitment. Human Resource Development Review, 14(4), 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M., Ingusci, E., Signore, F., Manuti, A., Giancaspro, M. L., Russo, V., Zito, M., & Cortese, C. G. (2020). Wellbeing costs of technology use during remote working: An investigation using the Italian translation of the technostress creators scale. Sustainability, 12(15), 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakrošienė, A., Bučiūnienė, I., & Goštautaitė, B. (2019). Working from home: Characteristics and outcomes of telework. International Journal of Manpower, 40(1), 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M. J., Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Roberts, J. A., & Chonko, L. B. (2009). The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: Evidence from the field. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(2), 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2015). Ethical leadership: Meta-analytic evidence of criterion-related and incremental validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 948–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. G., Zhu, W., Kwon, B., & Bang, H. (2023). Ethical leadership and follower unethical pro-organizational behavior: Examining the dual influence mechanisms of affective and continuance commitments. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(22), 4313–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivaz, M., Asadi, F., & Mansouri, P. (2020). Assessment of the relationship between nurses’ perception of ethical climate and job burnout in intensive care units. Investigación y Educación En Enfermería, 38(3), e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, C. W., Allan, B., Clark, M., Hertel, G., Hirschi, A., Kunze, F., Shockley, K., Shoss, M., Sonnentag, S., & Zacher, H. (2021). Pandemics: Implications for research and practice in industrial and organizational psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 14(1–2), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Reyes, J., Idrovo-Carlier, S., & Duque-Oliva, E. J. (2021). Remote work, work stress, and work–life during pandemic times: A Latin America situation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023a). Ethical leadership and benevolent climate. The mediating effect of creative self-efficacy and the moderator of continuance commitment. Revista Galega de Economía, 32(3), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023b). Relación entre liderazgo ético y motivación intrínseca: El rol mediador de la creatividad y el múltiple efecto moderador del compromiso de continuidad. Revista de Métodos Cuantitativos para la Economía y la Empresa, 36(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2024a). Clima ético benevolente y autoeficacia laboral. La mediación de la motivación intrínseca y la moderación del compromiso afectivo en el sector eléctrico colombiano. Lecturas de Economía, 1(101), 235–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2024b). Creativity and emotional exhaustion in virtual work environments: The ambiguous role of work autonomy. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(7), 2087–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2025). ¿El liderazgo y los climas éticos amortiguan o promueven el burnout en el Sector Eléctrico Colombiano? [Doctoral’s thesis, Universitat de Girona]. TDX (Tesis Doctorals en Xarxa). Available online: https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/694925 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Santiago-Torner, C., Corral-Marfil, J. A., Jiménez-Pérez, Y., & Tarrats-Pons, E. (2025a). Impact of ethical leadership on autonomy and self-efficacy in virtual work environments: The disintegrating effect of an egoistic climate. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., Corral-Marfil, J.-A., & Tarrats-Pons, E. (2024). Relationship between personal ethics and burnout: The unexpected influence of affective commitment. Administrative Sciences, 14(6), 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., González-Carrasco, M., & Miranda-Ayala, R. (2025b). Relationship between ethical climate and burnout: A new approach through work autonomy. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. (2017). Applying the job demands–resources model. Organizational Dynamics, 46(2), 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory–general survey. In C. Maslach, S. E. Jackson, & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), MBI manual (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2011). Work engagement: On how to better catch a slippery concept. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(1), 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A., & Melamed, S. (2006). A comparison of the construct validity of two burnout measures in two groups of professionals. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(2), 176–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevičienė, A., Grincevičienė, N., Diskienė, D., & Drūteikienė, G. (2024). The Influence of personal skills for telework on organisational commitment: The mediating effect of the perceived intensity of telework. JEEMS Journal of East European Management Studies, 28(4), 606–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T. W., Le Blanc, P. M., Schaufeli, W. B., & Schreurs, P. J. G. (2005). Are there causal relationships between the dimensions of the Maslach Burnout Inventory? A review and two longitudinal tests. Work & Stress, 19(3), 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresi, M., Pietroni, D., Barattucci, M., Giannella, V. A., & Pagliaro, S. (2019). Ethical climate(s), organizational identification, and employees’ behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(1), 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torlak, N. G., Kuzey, C., Dinç, M. S., & Güngörmüş, A. H. (2021). Effects of ethical leadership, job satisfaction and affective commitment on the turnover intentions of accountants. Journal of Modelling in Management, 16(2), 413–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. (2000). Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. California Management Review, 42(4), 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Elst, T., Verhoogen, R., Sercu, M., Van den Broeck, A., Baillien, E., & Godderis, L. (2017). Not extent of telecommuting, but job characteristics as proximal predictors of work-related well-being. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 59(10), e180–e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1), 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virick, M., DaSilva, N., & Arrington, K. (2010). Moderators of the curvilinear relation between extent of telecommuting and job and life satisfaction: The role of performance outcome orientation and worker type. Human Relations, 63(1), 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Liu, Y., Qian, J., & Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology, 70(1), 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the Job Demands–Resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model Summary | R | R2 | ΔR2 | F (df1, df2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: | Affective commitment (Y) | ||||

| Overall model | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 14.01 (3, 443) | <0.01 |

| Predictor | b | SE | t | p | 95% CI [LLCI, ULCI] |

| Constant | 22.50 | 3.17 | 7.01 | 0.01 | [16.27, 28.74] |

| Ethical Leadership (X) | 0.25 | 0.06 | 3.42 | 0.01 | [0.11, 0.39] |

| Telework Intensity (W) | −0.59 | 1.01 | −0.56 | 0.57 | [−1.60, 3.21] |

| Interaction (X × W) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.67 | [−0.07, 0.05] |

| Model Summary | R | R2 | ΔR2 | F (df1, df2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: | Emotional Exhaustion (Y) | ||||

| Overall model | 0.46 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 39.09 (3, 444) | <0.01 |

| Predictor | b | SE | t | p | 95% CI [LLCI, ULCI] |

| Constant | 15.46 | 3.65 | 4.23 | 0.01 | [8.29, 22.64] |

| Affective Commitment (X) | 0.27 | 0.12 | 2.25 | 0.02 | [0.04, 0.51] |

| Telework Intensity (W) | −2.49 | 1.08 | −2.29 | 0.02 | [−4.62, −0.35] |

| Interaction (X × W) | 0.08 | 0.04 | 2.14 | 0.03 | [0.06, 0.15] |

| Model Summary | R | R2 | ΔR2 | F (df1, df2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: | Emotional Exhaustion (Y) | ||||

| Overall model | 0.46 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 24.58 (5, 442) | <0.01 |

| Predictor | b | SE | t | p | 95% CI [LLCI, ULCI] |

| Constant | 24.53 | 4.30 | 4.13 | 0.01 | [4.32, 23.69] |

| Climate of principles (X) | 0.20 | 0.07 | 3.42 | 0.01 | [0.11, 0.39] |

| Telework Intensity (W) | −2.72 | 1.46 | −3.66 | 0.02 | [−1.60, −0.21] |

| Interaction (X × W) | −0.06 | 0.03 | −3.95 | 0.02 | [−0.11, −0.02] |

| Model Summary | R | R2 | ΔR2 | F (df1, df2) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: | Depersonalization (Y) | ||||

| Overall model | 0.58 | 0.34 | 0.12 | 35.79 (5, 442) | <0.01 |

| Predictor | b | SE | t | p | 95% CI [LLCI, ULCI] |

| Constant | 24.41 | 4.17 | 4.28 | 0.01 | [4.10, 23.01] |

| Climate of principles (X) | 0.26 | 0.07 | 4.32 | 0.01 | [0.21, 0.79] |

| Telework Intensity (W) | −2.12 | 1.66 | −3.26 | 0.02 | [−1.16, −0.31] |

| Interaction (X × W) | −0.05 | 0.02 | −3.25 | 0.02 | [−0.42, −0.12] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santiago-Torner, C. Moderating Effects of Telework Intensity on the Relationship Between Ethical Climate, Affective Commitment and Burnout in the Colombian Electricity Sector Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101409

Santiago-Torner C. Moderating Effects of Telework Intensity on the Relationship Between Ethical Climate, Affective Commitment and Burnout in the Colombian Electricity Sector Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101409

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantiago-Torner, Carlos. 2025. "Moderating Effects of Telework Intensity on the Relationship Between Ethical Climate, Affective Commitment and Burnout in the Colombian Electricity Sector Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101409

APA StyleSantiago-Torner, C. (2025). Moderating Effects of Telework Intensity on the Relationship Between Ethical Climate, Affective Commitment and Burnout in the Colombian Electricity Sector Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101409