Reflecting Emotional Intelligence: How Mindsets Navigate Academic Engagement and Burnout Among College Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

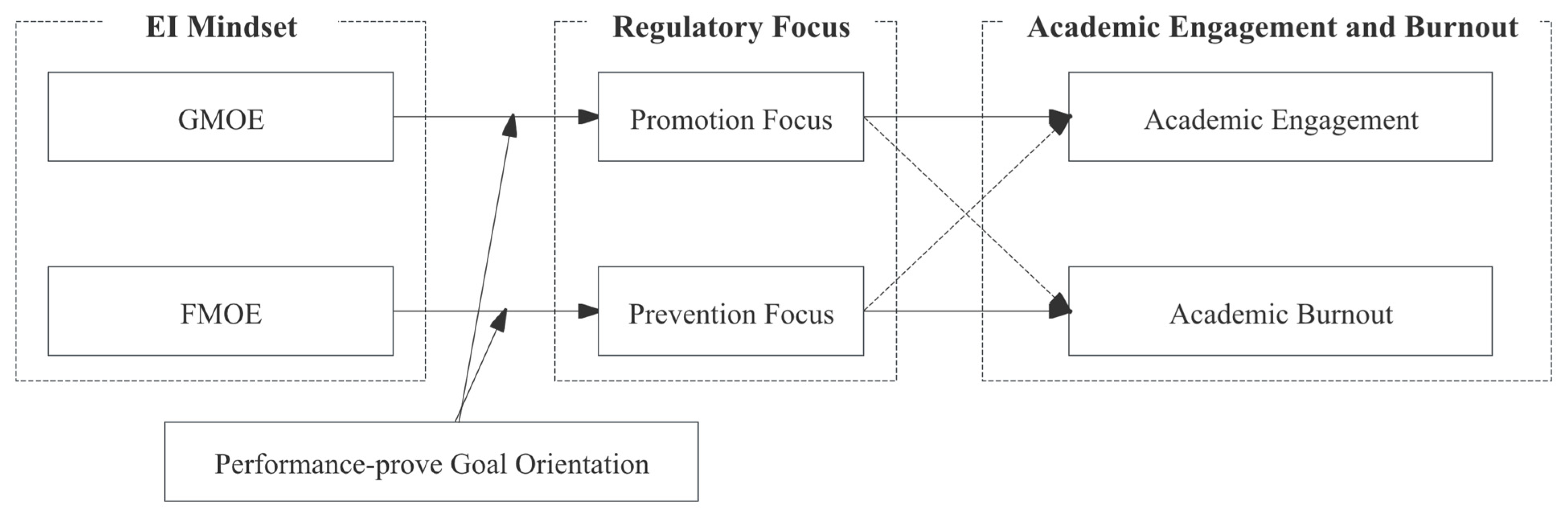

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Linking EI Mindsets with Academic Engagement and Burnout

2.2. The Mediating Role of Regulatory Focus

2.3. The Moderating Role of Performance-Prove Goal Orientation

3. Study 1

3.1. Samples and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Results

3.3.1. Manipulation Checks

3.3.2. Experimental Results

3.4. Discussion

4. Study 2

4.1. Samples and Procedure

4.2. Measures

4.3. Data Analysis

4.4. Results

4.4.1. Common Method Bias Test

4.4.2. Descriptive Analysis

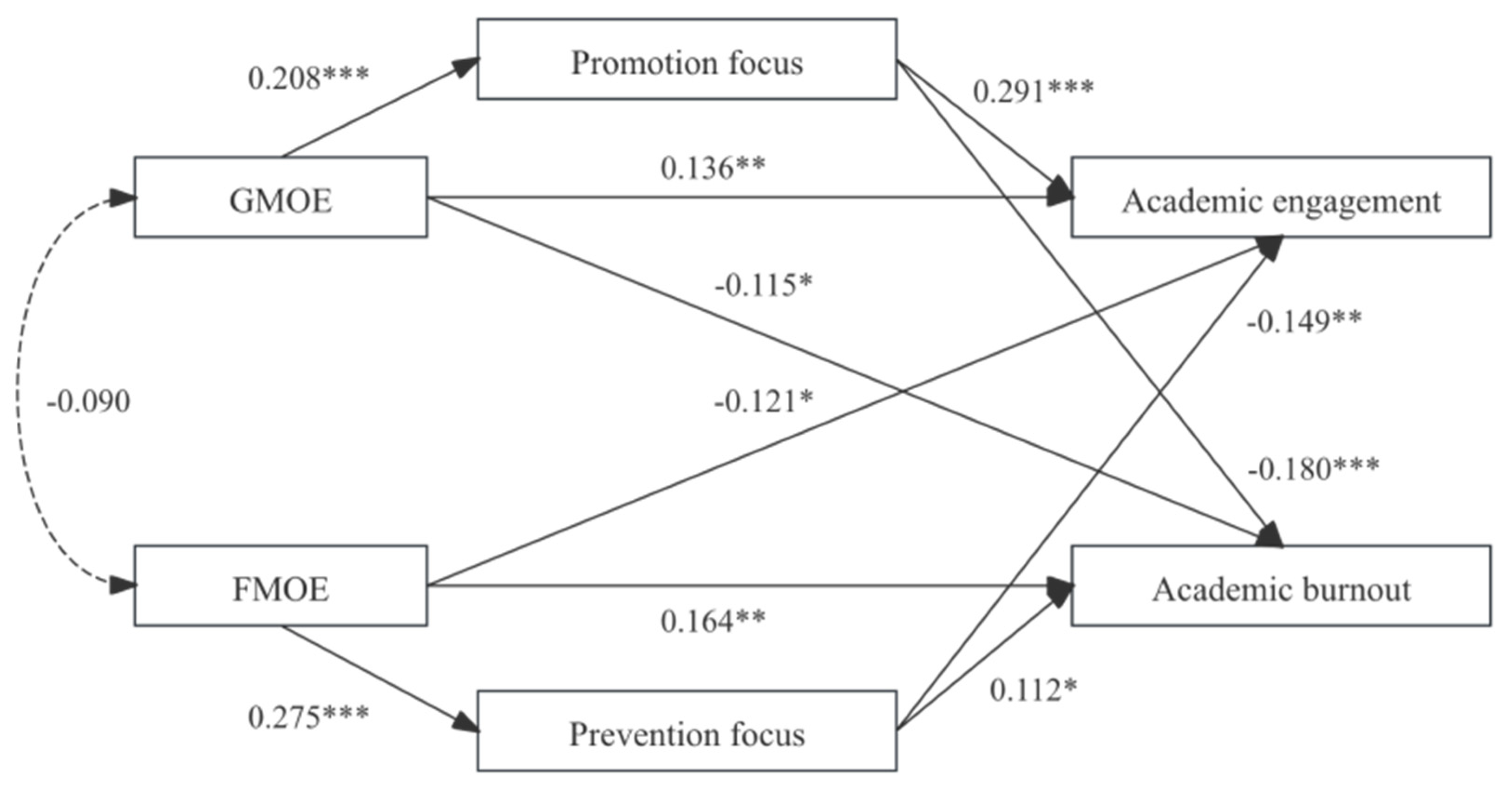

4.4.3. Main and Mediating Effects

4.4.4. Moderated Effects

4.4.5. Moderated Mediation Effects

4.5. Discussion

5. General Discussion

6. Theoretical Implications

7. Practical Implications

8. Limitations and Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EI | emotional intelligence |

| GMOE | growth mindset of emotional intelligence |

| FMOE | fixed mindset of emotional intelligence |

Appendix A. Supplementary Analysis: Incremental Predictive Validity of EI Mindsets for Academic Engagement and Burnout Beyond EI (Full Version)

Appendix A.1. Samples and Procedure

Appendix A.2. Measures

Appendix A.3. Results

| Variables | Academic Engagement | Academic Burnout | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Gender | −0.002 | 0.064 | 0.038 | 0.044 | −0.034 | −0.050 |

| Age | −0.058 | −0.057 | −0.061 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.049 |

| Discipline | −0.065 | −0.062 | −0.054 | 0.080 | 0.077 | 0.074 |

| EI | 0.326 ** | 0.215 ** | −0.384 ** | −0.319 ** | ||

| GMOE | 0.218 ** | |||||

| FMOE | 0.140 ** | |||||

| R2 | 0.032 | 0.211 | 0.333 | 0.038 | 0.248 | 0.292 |

| F | 1.296 | 7.740 *** | 11.503 *** | 1.536 | 9.541 *** | 9.498 *** |

| △R2 | 0.032 | 0.179 | 0.123 | 0.038 | 0.210 | 0.045 |

| △F | 1.296 | 26.233 *** | 21.175 *** | 1.536 | 32.322 *** | 7.266 ** |

Appendix A.4. Discussion

| 1 | Based on a separate sample of 121 undergraduates (Mage = 19.22; 62.81% male), we tested the incremental predictive validity of EI mindsets beyond EI. GMOE significantly improved the prediction of academic engagement (ΔR2 = 0.123, p < 0.001), and FMOE strengthened the capacity to predict academic burnout (ΔR2 = 0.045, p < 0.01). These findings support the incremental utility of EI mindsets beyond EI and demonstrate their distinct theoretical relevance for academic engagement and burnout. (See Appendix A for the full set of results.) |

References

- Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., Shiffman, S., Lerner, N., & Salovey, P. (2006). Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: A comparison of self-report and performance measures of emotional intelligence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4), 780–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockner, J., & Higgins, E. T. (2001). Regulatory focus theory: Implications for the study of emotions at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(1), 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broda, M., Yun, J., Schneider, B., Yeager, D. S., Walton, G. M., & Diemer, M. (2018). Reducing inequality in academic success for incoming college students: A randomized trial of growth mindset and belonging interventions. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 11(3), 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J. L., Billingsley, J., Banks, G. C., Knouse, L. E., Hoyt, C. L., Pollack, J. M., & Simon, S. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of growth mindset interventions: For whom, how, and why might such interventions work? Psychological Bulletin, 149(3–4), 174–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnette, J. L., O’boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2013). Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 655–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, R., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2015). Implicit theories and ability emotional intelligence. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A., & Faria, L. (2020). Implicit theories of emotional intelligence, ability and trait-emotional intelligence and academic achievement. Psihologijske Teme, 29(1), 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A., & Faria, L. (2022). The impact of implicit theories on students’ emotional outcomes. Current Psychology, 41(4), 2354–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A., & Faria, L. (2023). Trajectories of implicit theories of intelligence and emotional intelligence in secondary school. Social Psychology of Education, 26(1), 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A., & Faria, L. (2025). Implicit theories of emotional intelligence and students’ emotional and academic outcomes. Psychological Reports, 128(4), 2732–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, E., & Higgins, E. T. (1997). Regulatory focus and strategic inclinations: Promotion and prevention in decision-making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 69(2), 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnon, C., Dompnier, B., Gilliéron, O., & Butera, F. (2010). The interplay of mastery and performance goals in social comparison: A multiple-goal perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(1), 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De France, K., & Hollenstein, T. (2021). Implicit theories of emotion and mental health during adolescence: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Cognition and Emotion, 35(2), 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W., Lei, W., Guo, X., Li, X., Ge, W., & Hu, W. (2022). Effects of regulatory focus on online learning engagement of high school students: The mediating role of self-efficacy and academic emotions. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(3), 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, B., van Knippenberg, D., Hirst, G., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2015). Outperforming whom? A multilevel study of performance-prove goal orientation, performance, and the moderating role of shared team identification. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(6), 1811–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, P. E., Crawford, E. R., Seibert, S. E., Stoverink, A. C., & Campbell, E. M. (2021). Referents or role models? The self-efficacy and job performance effects of perceiving higher performing peers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(3), 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S. (2008). Can personality be changed? The role of beliefs in personality and change. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(6), 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekermans, G. (2009). Emotional intelligence across cultures: Theoretical and methodological considerations. In Assessing emotional intelligence: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 259–290). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, A. J., & Church, M. A. (1997). A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(1), 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giel, L. I., Noordzij, G., Noordegraaf-Eelens, L., & Denktaş, S. (2020). Fear of failure: A polynomial regression analysis of the joint impact of the perceived learning environment and personal achievement goal orientation. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 33(2), 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52(12), 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 30, pp. 1–46). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, E. T. (2000). Making a good decision: Value from fit. American Psychologist, 55(11), 1217–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, E., Scheiter, K., & Sassenberg, K. (2024). Promotion focus, but not prevention focus of teachers and students matters when shifting towards technology-based instruction in schools. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 22030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, C. L., Burnette, J. L., Nash, E., Becker, W., & Billingsley, J. (2023). Growth mindsets of anxiety: Do the benefits to individual flourishing come with societal costs? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 18(3), 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20(2), 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadpanah, S. (2023). The mediating role of academic passion in determining the relationship between academic self-regulation and goal orientation with academic burnout among English foreign language (EFL) learners. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 933334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Job, V., Bernecker, K., Miketta, S., & Friese, M. (2015). Implicit theories about willpower predict the activation of a rest goal following self-control exertion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(4), 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R. B., & dela Rosa, E. D. (2019). Are your emotions under your control or not? Implicit theories of emotion predict well-being via cognitive reappraisal. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knee, C. R., Patrick, H., Vietor, N. A., & Neighbors, C. (2004). Implicit theories of relationships: Moderators of the link between conflict and commitment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(5), 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneeland, E. T., & Kisley, M. A. (2023). Lay perspectives on emotion: Past, present, and future research directions. Motivation and Emotion, 47(3), 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordsalarzehi, F., Salehipour, S., Hamedani, M. A., Jahromi, R. Z., Arbabisarjou, A., & Ghaljeh, M. (2025). The impact of academic skills training on academic self-efficacy and motivation in nursing and midwifery students: A quasi-experimental study. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 14(1), 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümmel, E., & Kimmerle, J. (2020). The effects of a university’s self-presentation and applicants’ regulatory focus on emotional, behavioral, and cognitive student engagement. Sustainability, 12(23), 10045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J. E. (2022). The impact of career plateau on job burnout in the COVID-19 pandemic: A moderating role of regulatory focus. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaj, K., Chang, C. H., & Johnson, R. E. (2012). Regulatory focus and work-related outcomes: A review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 998–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, K. S., Wong, C. S., & Song, L. J. (2004). The construct and criterion validity of emotional intelligence and its potential utility for management studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. K. (2022). The effects of social comparison orientation on psychological well-being in social networking sites: Serial mediation of perceived social support and self-esteem. Current Psychology, 41(9), 6247–6259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, R., Yang, L., & Wu, L. (2005). The relationship between college students’ professional commitment and learning burnout, and the development of a measurement scale. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 37(5), 632–636. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B., Shah, T. A., & Shoaib, M. (2024). Creative leadership, creative mindset and creativity: A self-regulatory focus perspective. Current Psychology, 43(29), 24375–24389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Yao, M., Li, R., & Zhang, L. (2020). The relationship between regulatory focus and learning engagement among Chinese adolescents. Educational Psychology, 40(4), 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, P., Jordan, C. H., & Kunda, Z. (2002). Motivation by positive or negative role models: Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCann, C., Jiang, Y., Brown, L. E., Double, K. S., Bucich, M., & Minbashian, A. (2020). Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(2), 150–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnamara, B. N., & Burgoyne, A. P. (2023). Do growth mindset interventions impact students’ academic achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis with recommendations for best practices. Psychological Bulletin, 149(3–4), 133–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I. M., Youssef-Morgan, C. M., Chambel, M. J., & Marques-Pinto, A. (2019). Antecedents of academic performance of university students: Academic engagement and psychological capital resources. Educational Psychology, 39(8), 1047–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q., & Zhang, Q. (2023). The influence of academic self-efficacy on university students’ academic performance: The mediating effect of academic engagement. Sustainability, 15(7), 5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moumne, S., Hall, N., Böke, B. N., Bastien, L., & Heath, N. (2021). Implicit theories of emotion, goals for emotion regulation, and cognitive responses to negative life events. Psychological Reports, 124(4), 1588–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, D., & Fayant, M. P. (2010). On being exposed to superior others: Consequences of self-threatening upward social comparisons. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(8), 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J. M., Komissarov, S., Cook, S. L., & Murray, B. L. (2022). Predictors for growth mindset and sense of belonging in college students. Journal of Pedagogical Sociology and Psychology, 4(1), 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertig, D., Schüler, J., Schnelle, J., Brandstätter, V., Roskes, M., & Elliot, A. J. (2013). Avoidance goal pursuit depletes self-regulatory resources. Journal of Personality, 81(4), 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, N., Oberhoffer-Fritz, R., Reiner, B., & Schulz, T. (2025). Stress, student burnout and study engagement–a cross-sectional comparison of university students of different academic subjects. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunesku, D., Walton, G. M., Romero, C., Smith, E. N., Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2015). Mind-set interventions are a scalable treatment for academic underachievement. Psychological Science, 26(6), 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K. V., Furnham, A., & Mavroveli, S. (2007). Trait emotional intelligence: Moving forward in the field of EI. Emotional Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns, 4, 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quílez-Robres, A., Usán, P., Lozano-Blasco, R., & Salavera, C. (2023). Emotional intelligence and academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 49, 101355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-de-Cózar, S., Merino-Cajaraville, A., & Salguero-Pazos, M. R. (2023). Avoiding academic burnout: Academic factors that enhance university student engagement. Behavioral Sciences, 13(12), 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P. E., & Sluyter, D. J. (1997). Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Ruiz, M. J., Pérez-González, J. C., & Petrides, K. V. (2010). Trait emotional intelligence profiles of students from different university faculties. Australian Journal of Psychology, 62(1), 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisk, V. F., Burgoyne, A. P., Sun, J., Butler, J. L., & Macnamara, B. N. (2018). To what extent and under which circumstances are growth mind-sets important to academic achievement? Two meta-analyses. Psychological Science, 29(4), 549–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickhouser, J. E., & Zell, E. (2015). Self-evaluative effects of dimensional and social comparison. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 59, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue-Chan, C., Wood, R. E., & Latham, G. P. (2012). Effect of a coach’s regulatory focus and an individual’s implicit person theory on individual performance. Journal of Management, 38(3), 809–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S. Y., Li, Y. X., & Choi, J. N. (2024). Upward social comparison toward proactive and reactive knowledge sharing: The roles of envy and goal orientations. Journal of Business Research, 170, 114314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghani, A., & Razavi, M. R. (2022). The effect of metacognitive skills training of study strategies on academic self-efficacy and academic engagement and performance of female students in Taybad. Current Psychology, 41(12), 8784–8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, M., John, O. P., Srivastava, S., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Implicit theories of emotion: Affective and social outcomes across a major life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubago-Jimenez, J. L., Zurita-Ortega, F., Ortega-Martin, J. L., & Melguizo-Ibañez, E. (2024). Impact of emotional intelligence and academic self-concept on the academic performance of educational sciences undergraduates. Heliyon, 10(8), e29476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandeWalle, D. (1997). Development and validation of a work domain goal orientation instrument. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 57(6), 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestad, L., & Bru, E. (2024). Teachers’ support for growth mindset and its links with students’ growth mindset, academic engagement, and achievements in lower secondary school. Social Psychology of Education, 27(4), 1431–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizoso, C., Arias-Gundín, O., & Rodríguez, C. (2019). Exploring coping and optimism as predictors of academic burnout and performance among university students. Educational Psychology, 39(6), 768–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A. M., Foster Thompson, L., Rudolph, J. V., Whelan, T. J., Behrend, T. S., & Gissel, A. L. (2013). When big brother is watching: Goal orientation shapes reactions to electronic monitoring during online training. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(4), 642–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q., Pang, C., Zeng, W., Li, Q., Wu, S., & Xiao, X. (2025). Burnout among VET pathway university students: The role of academic stress and school-life satisfaction. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A., & Dhar, R. L. (2021). Linking frontline hotel employees’ job crafting to service recovery performance: The roles of harmonious passion, promotion focus, hotel work experience, and gender. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 47, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M., & Xu, Y. (2024). Method bias mechanisms and procedural remedies. Sociological Methods & Research, 53(1), 235–278. [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda, Y., & Goegan, L. D. (2023). The relationship between regulatory focus, perfectionism, and school burnout. Social Psychology of Education, 26(4), 903–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2020). What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? American Psychologist, 75(9), 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2013). An implicit theories of personality intervention reduces adolescent aggression in response to victimization and exclusion. Child Development, 84(3), 970–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarrinabadi, N., & Saberi Dehkordi, E. (2024). The effects of reference of comparison (self-referential vs. normative) and regulatory focus (promotion vs. prevention) feedback on EFL learners’ willingness to communicate. Language Teaching Research, 28(2), 556–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedelius, C. M., Müller, B. C., & Schooler, J. W. (Eds.). (2017). The science of lay theories: How beliefs shape our cognition, behavior, and health. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., Guo, G., Fu, M., Yang, W., Li, C., & Jiang, Y. (2025). Help-seeking matters: Exploring the dual effects of stress mindsets on academic behaviors. Psychological Reports, 00332941251343550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Qin, X., & Ren, P. (2018). Adolescents’ academic engagement mediates the association between Internet addiction and academic achievement: The moderating effect of classroom achievement norm. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. R., & Namasivayam, K. (2012). The relationship of chronic regulatory focus to work–family conflict and job satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(2), 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, R., Liu, R. D., Ding, Y., Wang, J., Liu, Y., & Xu, L. (2017). The mediating roles of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions in the relation between basic psychological needs satisfaction and learning engagement among Chinese adolescent students. Learning and Individual Differences, 54, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J., Wen, J., & Li, K. (2023). Do achievement goals differently orient students’ academic engagement through learning strategy and academic self-efficacy and vary by grade. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 4779–4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (T1) | 1.56 | 0.50 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2. Grade (T1) | 2.73 | 1.15 | 0.033 | 1 | |||||||||

| 3. Discipline (T1) | 2.42 | 1.04 | 0.304 ** | −0.020 | 1 | ||||||||

| 4. Age (T1) | 20.93 | 3.5 | −0.019 | 0.351 ** | 0.050 | 1 | |||||||

| 5. GMOE (T1) | 3.13 | 0.98 | 0.007 | −0.004 | −0.024 | −0.018 | 1 | ||||||

| 6. FMOE (T1) | 3.63 | 0.88 | −0.052 | −0.016 | −0.033 | −0.003 | −0.072 | 1 | |||||

| 7. Promotion focus (T2) | 3.26 | 0.75 | −0.016 | 0.053 | −0.028 | 0.003 | 0.193 ** | −0.028 | 1 | ||||

| 8. Prevention focus (T2) | 3.02 | 0.73 | 0.048 | 0.125 ** | −0.020 | 0.068 | −0.032 | 0.239 ** | −0.114 * | 1 | |||

| 9. Performance-prove goal orientation (T2) | 4.07 | 1.26 | −0.028 | 0.020 | −0.019 | −0.028 | −0.083 | −0.088 * | −0.011 | 0.075 | 1 | ||

| 10. Academic engagement (T3) | 3.15 | 0.75 | 0.070 | 0.024 | 0.046 | −0.013 | 0.205 ** | −0.168 ** | 0.308 ** | −0.205 ** | −0.051 | 1 | |

| 11. Academic burnout (T3) | 3.10 | 0.74 | 0.071 | 0.015 | 0.029 | 0.031 | −0.165 ** | 0.191 ** | −0.201 ** | 0.163 ** | 0.021 | −0.134 ** | 1 |

| Paths | Effect | Boot SE | Bias-Corrected 95%CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | p | |||

| GMOE → Promotion focus → Academic engagement | 0.045 | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.074 | 0.000 |

| GMOE → Promotion focus → Academic burnout | −0.026 | 0.009 | −0.049 | −0.011 | 0.000 |

| FMOE → Prevention focus → Academic burnout | 0.023 | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.054 | 0.035 |

| FMOE → Prevention focus → Academic engagement | −0.033 | 0.013 | −0.065 | −0.012 | 0.002 |

| Variables | Promotion Focus | Prevention Focus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Gender | −0.018 | −0.022 | −0.010 | 0.083 | 0.104 | 0.086 |

| Grade | 0.038 | 0.038 | 0.031 | 0.071 * | 0.071 * | 0.070 * |

| Discipline | −0.016 | −0.012 | −0.03 | −0.026 | −0.022 | −0.016 |

| Age | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.002 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| GMOE | 0.147 *** | 0.429 *** | ||||

| FMOE | 0.211 *** | −0.056 | ||||

| Performance-prove goal orientation | 0.002 | 0.224 * | 0.057 * | −0.208 * | ||

| GMOE × performance-prove goal orientation | −0.068 * | |||||

| FMOE × performance-prove goal orientation | 0.073 ** | |||||

| R2 | 0.004 | 0.041 | 0.052 | 0.020 | 0.088 | 0.103 |

| F | 0.487 | 3.557 ** | 3.924 *** | 2.501 * | 8.067 *** | 8.155 *** |

| Mediation Paths | Performance-Prove Goal Orientation | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMOE → Promotion focus →Academic engagement | M − SD | 0.064 | 0.016 | 0.033 | 0.096 |

| M | 0.040 | 0.011 | 0.019 | 0.062 | |

| M + SD | 0.021 | 0.013 | −0.007 | 0.048 | |

| FMOE → Prevention focus → Academic burnout | M − SD | 0.020 | 0.010 | 0.003 | 0.043 |

| M | 0.031 | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.060 | |

| M + SD | 0.040 | 0.018 | 0.007 | 0.076 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, W.; Guo, G.; Yang, W. Reflecting Emotional Intelligence: How Mindsets Navigate Academic Engagement and Burnout Among College Students. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091261

Jiang Y, Zhang J, Zheng W, Guo G, Yang W. Reflecting Emotional Intelligence: How Mindsets Navigate Academic Engagement and Burnout Among College Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091261

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Yunshan, Jianwei Zhang, Wenfeng Zheng, Guangxia Guo, and Wenya Yang. 2025. "Reflecting Emotional Intelligence: How Mindsets Navigate Academic Engagement and Burnout Among College Students" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091261

APA StyleJiang, Y., Zhang, J., Zheng, W., Guo, G., & Yang, W. (2025). Reflecting Emotional Intelligence: How Mindsets Navigate Academic Engagement and Burnout Among College Students. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091261