Muscle Dysmorphia, Obsessive–Compulsive Traits, and Anabolic Steroid Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

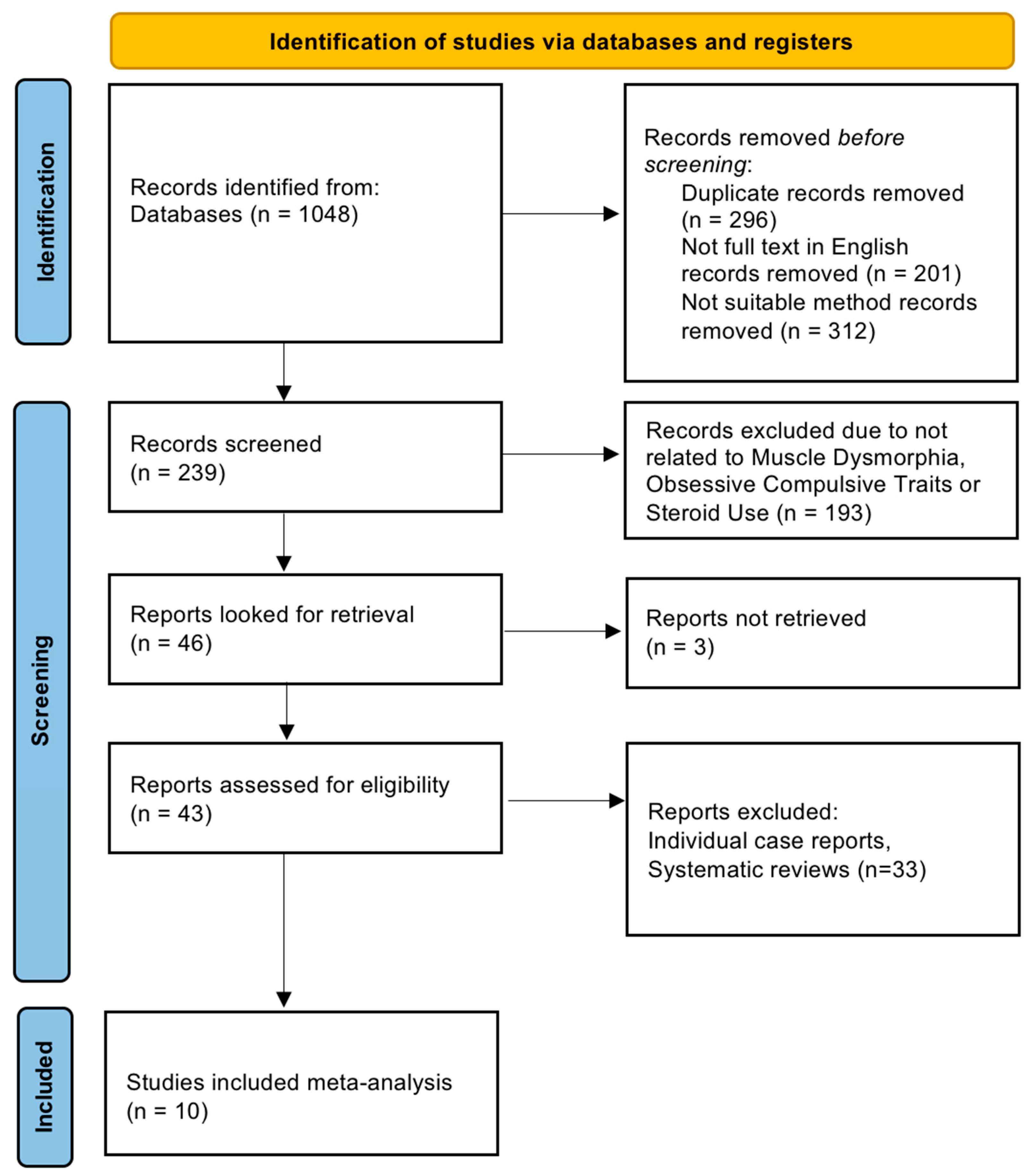

2.4. Screening and Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality and Bias Assessment

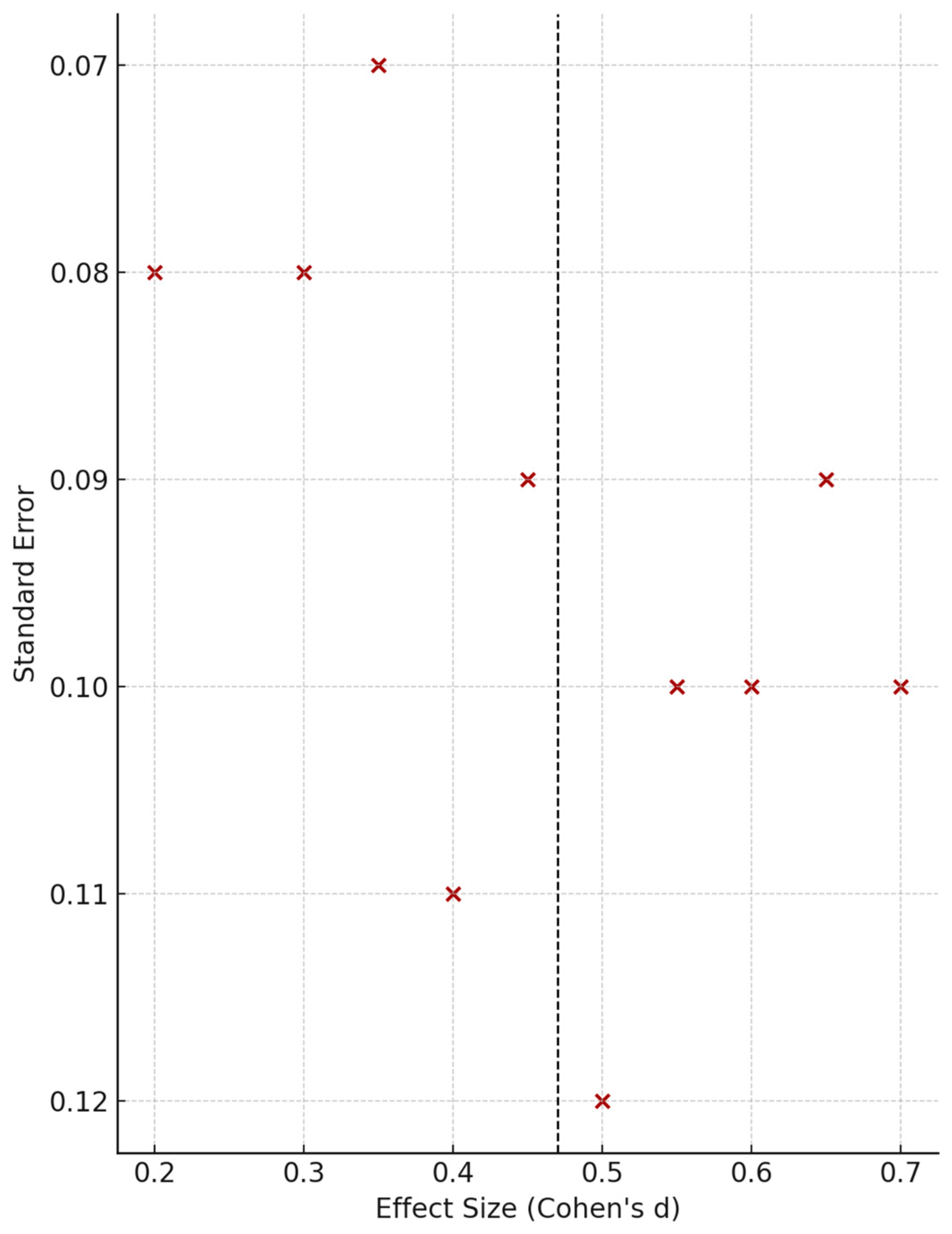

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

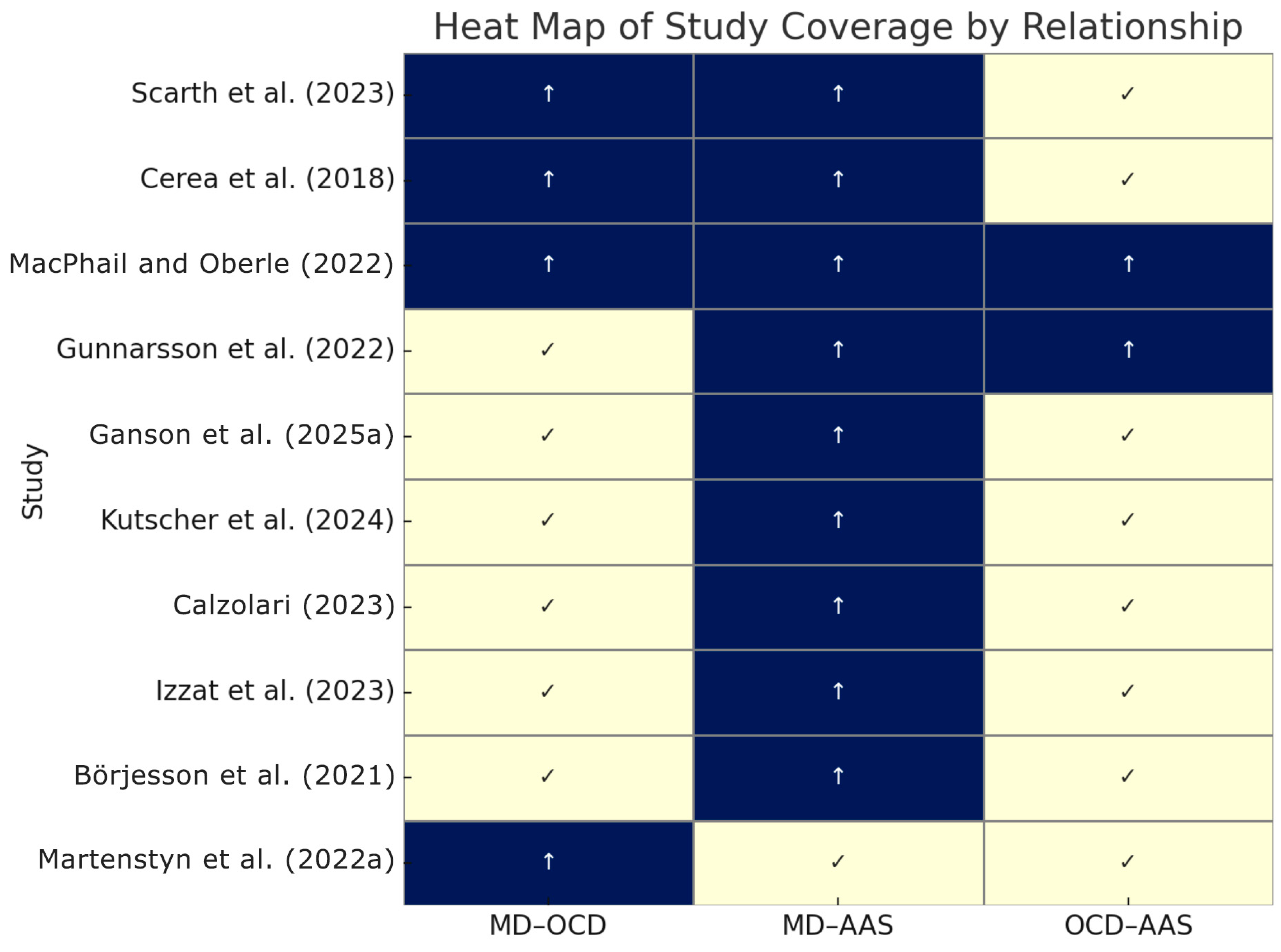

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.1.1. Study Samples and Measures

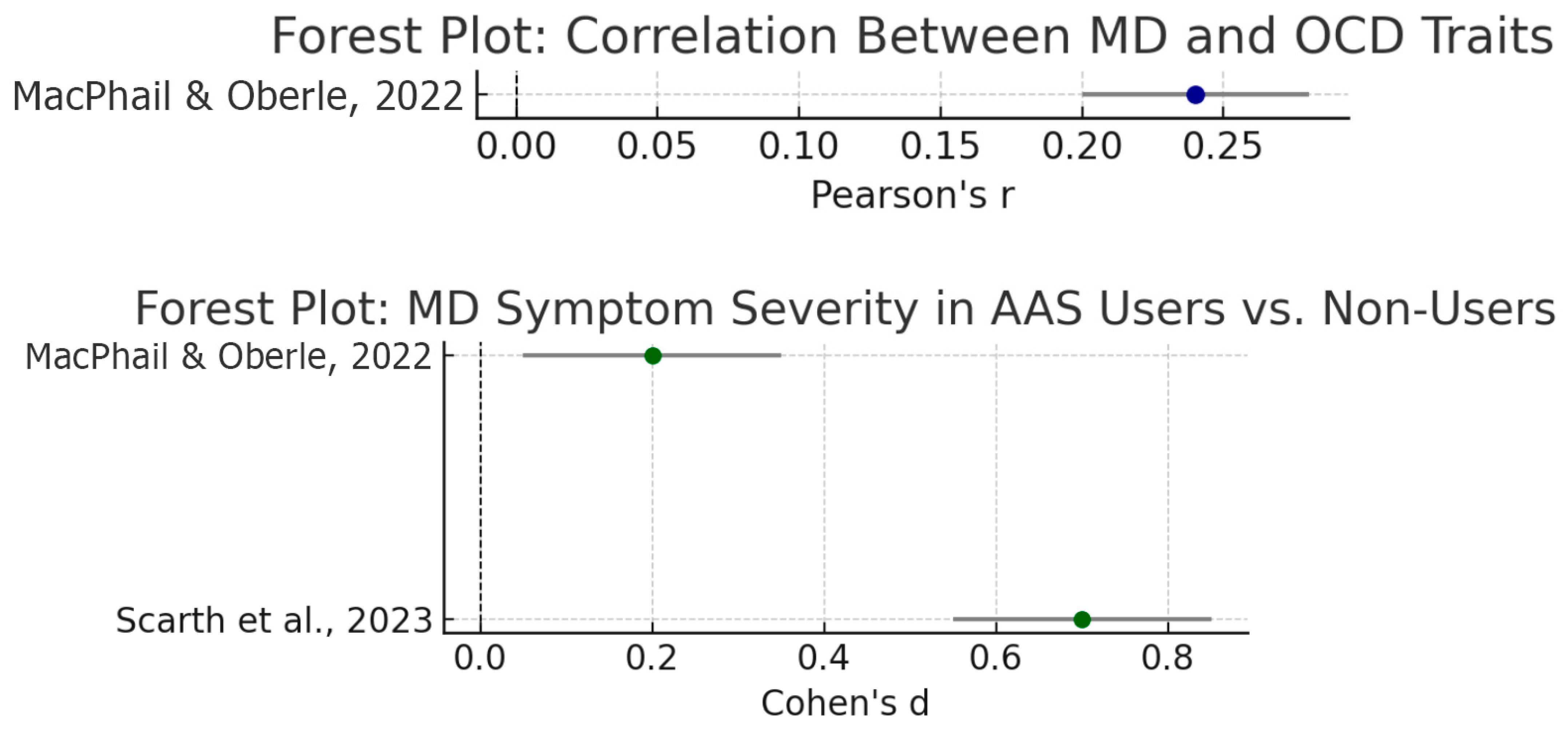

3.1.2. Associations Between MD, OC Traits, and AAS Use

3.1.3. Moderator and Subgroup Analyses

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.3. Narrative Synthesis

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Muscle Dysmorphia and OCD Traits

4.2. Muscle Dysmorphia and AAS/PED Use

4.3. Integration

4.4. Clinical and Public Health Implications

4.5. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ainsworth, N. P., Thrower, S. N., & Petróczi, A. (2022). Two sides of the same coin: A qualitative exploration of experiential and perceptual factors which influence the clinical interaction between physicians and anabolic-androgenic steroid using patients in the UK. Emerging Trends in Drugs, Addictions, and Health, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, G. D., Amico, F., Cocimano, G., Liberto, A., Maglietta, F., Esposito, M., Rosi, G. L., Di Nunno, N., Salerno, M., & Montana, A. (2021). Adverse effects of anabolic-androgenic steroids: A literature review. Healthcare, 9(1), 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, J. M. X., Kimergård, A., & Deluca, P. (2022). Prevalence of anabolic steroid users seeking support from physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 12(7), e056445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M., Yabancı Ayhan, N., Sarıyer, E. T., Çolak, H., & Çevik, E. (2022). The effect of bigorexia nervosa on eating attitudes and physical activity: A study on university students. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 2022(1), 6325860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badenes-Ribera, L., Rubio-Aparicio, M., Sanchez-Meca, J., Fabris, M. A., & Longobardi, C. (2019). The association between muscle dysmorphia and eating disorder symptomatology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(3), 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blashill, A. J., Grunewald, W., Fang, A., Davidson, E., & Wilhelm, S. (2020). Conformity to masculine norms and symptom severity among men diagnosed with muscle dysmorphia vs. body dysmorphic disorder. PLoS ONE, 15(8), e0237651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, P., Llewellyn, W., & Van Mol, P. (2016). Anabolic androgenic steroid-induced hepatotoxicity. Medical Hypotheses, 93, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, P., Smit, D. L., & de Ronde, W. (2022). Anabolic–androgenic steroids: How do they work and what are the risks? Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13, 1059473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnecaze, A. K., O’Connor, T., & Burns, C. A. (2021). Harm reduction in male patients actively using anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS) and performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs): A review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(7), 2055–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottoms, L., Prat Pons, M., Fineberg, N. A., Pellegrini, L., Fox, O., Wellsted, D., Drummond, L. M., Reid, J., Baldwin, D. S., Hou, R., Chamberlain, S., Sireau, N., Grohmann, D., & Laws, K. R. (2023). Effects of exercise on obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 27(3), 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börjesson, A., Ekebergh, M., Dahl, M. L., Ekström, L., Lehtihet, M., & Vicente, V. (2021b). Women’s experiences of using anabolic androgenic steroids. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 656413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brytek-Matera, A., Staniszewska, A., & Hallit, S. (2020). Identifying the profile of orthorexic behavior and “normal” eating behavior with cluster analysis: A cross-sectional study among polish adults. Nutrients, 12(11), 3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadman, J., & Turner, C. (2025). A clinician’s quick guide to evidence-based approaches: Body dysmorphic disorder. Clinical Psychologist, 29(1), 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzolari, F. (2023). Muscles that matter: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of emotions and experiences of female bodybuilders in Italy. Connexion: Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 12(1), 260869. Available online: https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/MFUconnexion/article/view/260869 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Carvalho, A. (2023). The appearance and enhancing use ideal of drugs image-of anxiety, the and perfect excessive performance. In The body in the mind: Exercise addiction, body image and the use of enhancement drugs (p. 77). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castle, D., Beilharz, F., Phillips, K. A., Brakoulias, V., Drummond, L. M., Hollander, E., Ioannidis, K., Pallanti, S., Chamberlain, S. R., Rossell, S. L., Veale, D., Wilhelm, S., Van Ameringen, M., Dell’Osso, B., Menchon, J. M., & Fineberg, N. A. (2021). Body dysmorphic disorder: A treatment synthesis and consensus on behalf of the international college of obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders and the obsessive compulsive and related disorders network of the European college of neuropsychopharmacology. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 36(2), 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerea, S., Bottesi, G., Pacelli, Q. F., Paoli, A., & Ghisi, M. (2018). Muscle dysmorphia and its associated psychological features in three groups of recreational athletes. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 8877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, C. G., Grieve, F. G., Derryberry, W. P., & Pegg, P. O. (2009). Are anxiety and obsessive-compulsive symptoms related to muscle dysmorphia. International Journal of Men’s Health, 8(2), 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M., Eddy, K. T., Thomas, J. J., Franko, D. L., Carron-Arthur, B., Keshishian, A. C., & Griffiths, K. M. (2020). Muscle dysmorphia: A systematic and meta-analytic review of the literature to assess diagnostic validity. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(10), 1583–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coquet, R., Roussel, P., & Ohl, F. (2018). Understanding the paths to appearance-and performance-enhancing drug use in bodybuilding. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corazza, O., Simonato, P., Demetrovics, Z., Mooney, R., Van De Ven, K., Roman-Urrestarazu, A., Rácmolnár, L., De Luca, I., Cinosi, E., Santacroce, R., Marini, M., Wellsted, D., Sullivan, K., Bersani, G., & Martinotti, G. (2019). The emergence of exercise addiction, body dysmorphic disorder, and other image-related psychopathological correlates in fitness settings: A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE, 14(4), e0213060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L., Piatkowski, T., & McVeigh, J. (2024). “I would never go to the doctor and speak about steroids”: Anabolic androgenic steroids, stigma and harm. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, J., Reynaud, D., Legigan, C., O’Brien, K., & Michel, G. (2023). “Muscle Pics”, a new body-checking behavior in muscle dysmorphia? L’encephale, 49(3), 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzzolaro, M. (2018). Body dysmorphic disorder and muscle dysmorphia. In Body image, eating, and weight: A guide to assessment, treatment, and prevention (pp. 67–84). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakın, G., Juwono, I. D., Potenza, M. N., & Szabo, A. (2021). Exercise addiction and perfectionism: A systematic review of the literature. Current Addiction Reports, 8(1), 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınaroğlu, M., Yılmazer, E., Ülker, S. V., Ahlatcıoğlu, E. N., & Sayar, G. H. (2024). Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy in reducing muscle dysmorphia symptoms among Turkish gym goers: A pilot study. Acta Psychologica, 250, 104542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, G., Dash, S., & Meeten, F. (2014). Obsessive compulsive disorder. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dèttore, D., Fabris, M. A., & Santarnecchi, E. (2020). Differential prevalence of depressive and narcissistic traits in competing and non-competing bodybuilders in relation to muscle dysmorphia levels. Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 20(2), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, B. J., & Baghurst, T. (2016). The disordered-eating, obsessive-compulsive, and body dysmorphic characteristics of muscle dysmorphia: A bimodal perspective. New Male Studies, 5(1), 68–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dinardi, J. S., Egorov, A. Y., & Szabo, A. (2021). The expanded interactional model of exercise addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10(3), 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, M. A., Badenes-Ribera, L., Longobardi, C., Demuru, A., Dawid Konrad, Ś., & Settanni, M. (2022a). Homophobic bullying victimization and muscle Dysmorphic concerns in men having sex with men: The mediating role of paranoid ideation. Current Psychology, 41, 3577–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, M. A., Longobardi, C., Badenes-Ribera, L., & Settanni, M. (2022b). Prevalence and co-occurrence of different types of body dysmorphic disorder among men having sex with men. Journal of Homosexuality, 69(1), 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, M. A., Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., & Settanni, M. (2018). Attachment style and risk of muscle dysmorphia in a sample of male bodybuilders. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(2), 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineberg, N. A., Hengartner, M. P., Bergbaum, C. E., Gale, T. M., Gamma, A., Ajdacic-Gross, V., Rössler, W., & Angst, J. (2013). A prospective population-based cohort study of the prevalence, incidence and impact of obsessive-compulsive symptomatology. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 17(3), 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A., Shorter, G., & Griffiths, M. (2015). Muscle dysmorphia: Could it be classified as an addiction to body image? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganson, K. T., Mitchison, D., Rodgers, R. F., Murray, S. B., Testa, A., & Nagata, J. M. (2025a). Prevalence and correlates of muscle dysmorphia in a sample of boys and men in Canada and the United States. Journal of Eating Disorders, 13(1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganson, K. T., Testa, A., Rodgers, R. F., & Nagata, J. M. (2025b). Associations between muscularity-oriented social media content and muscle dysmorphia among boys and men. Body Image, 53, 101903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, J., Alvarez-Rayón, G., Camacho-Ruíz, J., Amaya-Hernández, A., & Mancilla-Díaz, J. M. (2017). Muscle dysmorphia and use of ergogenics substances. A systematic review. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría (English Ed.), 46(3), 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestsdottir, S., Kristjansdottir, H., Sigurdsson, H., & Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2021). Prevalence, mental health and substance use of anabolic steroid users: A population-based study on young individuals. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 49(5), 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M., Ferrandes, A., & D’Amico, S. (2024). Mirror, mirror on the wall: The role of narcissism, muscle dysmorphia, and self-esteem in bodybuilders’ muscularity-oriented disordered eating. Current Psychology, 43, 32697–32706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martí, I., Fernández-Bustos, J. G., Jordán, O. R. C., & Sokolova, M. (2018). Muscle dysmorphia: Detection of the use-abuse of anabolic adrogenic steroids in a Spanish sample. Adicciones, 30(4), 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, W., & Blashill, A. J. (2021). Muscle dysmorphia. In Eating disorders in boys and men (pp. 103–115). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, B., Entezarjou, A., Fernández-Aranda, F., Jiménez-Murcia, S., Kenttä, G., & Håkansson, A. (2022). Understanding exercise addiction, psychiatric characteristics and use of anabolic androgenic steroids among recreational athletes–An online survey study. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4, 903777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S., Kamionka, A., Xue, Q., Izydorczyk, B., Lipowska, M., & Lipowski, M. (2025). Body image and risk of exercise addiction in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 14(1), 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, B. D., Diehl, D., Weaver, K., & Briggs, M. (2013). Exercise dependence and muscle dysmorphia in novice and experienced female bodybuilders. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2(4), 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havnes, I. A., Jørstad, M. L., McVeigh, J., Van Hout, M. C., & Bjørnebekk, A. (2020). The anabolic androgenic steroid treatment gap: A national study of substance use disorder treatment. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 14, 1178221820904150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzat, N., Abu-Farha, R., Harahsheh, M. A. M., & Thiab, S. (2023). A qualitative assessment of anabolic–androgenic steroid use among gym users in Jordan: Motives, perception, and safety. International Journal of Legal Medicine, 137(5), 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanayama, G., Brower, K. J., Wood, R. I., Hudson, J. I., & Pope, H. G., Jr. (2009). Anabolic–androgenic steroid dependence: An emerging disorder. Addiction, 104(12), 1966–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutscher, E., Arshed, A., Greene, R. E., & Kladney, M. (2024). Exploring anabolic androgenic steroid use among cisgender gay, bisexual, and queer men. JAMA Network Open, 7(5), e2411088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, E. C., Frampton, I., Verplanken, B., & Haase, A. M. (2017). How extreme dieting becomes compulsive: A novel hypothesis for the role of anxiety in the development and maintenance of anorexia nervosa. Medical Hypotheses, 108, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., & Settanni, M. (2017). Muscle dysmorphia and psychopathology: Findings from an Italian sample of male bodybuilders. Psychiatry Research, 256, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macho, J., Mudrak, J., & Slepicka, P. (2021). Enhancing the self: Amateur bodybuilders making sense of experiences with appearance and performance-enhancing drugs. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhail, D. C., & Oberle, C. D. (2022). Seeing Shred: Differences in muscle dysmorphia, orthorexia nervosa, depression, and obsessive-compulsive tendencies among groups of weightlifting athletes. Performance Enhancement & Health, 10(1), 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martenstyn, J. A., Aouad, P., Touyz, S., & Maguire, S. (2022a). Treatment of compulsive exercise in eating disorders and muscle dysmorphia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 29(2), 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martenstyn, J. A., Maguire, S., & Griffiths, S. (2022b). A qualitative investigation of the phenomenology of muscle dysmorphia: Part 1. Body Image, 43, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martenstyn, J. A., Russell, J., Tran, C., Griffiths, S., & Maguire, S. (2025). Evaluation of an 8-week telehealth cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) program for adults with muscle dysmorphia: A pilot and feasibility study. Body Image, 52, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martenstyn, J. A., Touyz, S., & Maguire, S. (2021). Treatment of compulsive exercise in eating disorders and muscle dysmorphia: Protocol for a systematic review. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesce, M., Cerniglia, L., & Cimino, S. (2022). Body image concerns: The impact of digital technologies and psychopathological risks in a normative sample of adolescents. Behavioral Sciences, 12(8), 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L., Murray, S. B., Cobley, S., Hackett, D., Gifford, J., Capling, L., & O’Connor, H. (2017). Muscle dysmorphia symptomatology and associated psychological features in bodybuilders and non-bodybuilder resistance trainers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 47(2), 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchison, D., Mond, J., Griffiths, S., Hay, P., Nagata, J. M., Bussey, K., Trompeter, N., Lonergan, A., & Murray, S. B. (2022). Prevalence of muscle dysmorphia in adolescents: Findings from the EveryBODY study. Psychological Medicine, 52(14), 3142–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S. B., Griffiths, S., Mond, J. M., Kean, J., & Blashill, A. J. (2016). Anabolic steroid use and body image psychopathology in men: Delineating between appearance-versus performance-driven motivations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 165, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, S. B., Rieger, E., Karlov, L., & Touyz, S. W. (2013). An investigation of the transdiagnostic model of eating disorders in the context of muscle dysmorphia. European Eating Disorders Review, 21(2), 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, J. M., McGuire, F. H., Lavender, J. M., Brown, T. A., Murray, S. B., Greene, R. E., Compte, E. J., Flentje, A., Lubensky, M. E., Obedin-Maliver, J., & Lunn, M. R. (2022). Appearance and performance-enhancing drugs and supplements, eating disorders, and muscle dysmorphia among gender minority people. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(5), 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, B. S., Hildebrandt, T., & Wallisch, P. (2022). Anabolic–androgenic steroid use is associated with psychopathy, risk-taking, anger, and physical problems. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 9133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olave, L., Estévez, A., Momeñe, J., Muñoz-Navarro, R., Gómez-Romero, M. J., Boticario, M. J., & Iruarrizaga, I. (2021). Exercise addiction and muscle dysmorphia: The role of emotional dependence and attachment. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 681808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivardia, R. (2001). Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the largest of them all? The features and phenomenology of muscle dysmorphia. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 9(5), 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivardia, R., Pope, H. G., Jr., & Hudson, J. I. (2000). Muscle dysmorphia in male weightlifters: A case-control study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(8), 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Larissa, S., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, P. J., Lund, B. C., Deninger, M. J., Kutscher, E. C., & Schneider, J. (2005). Anabolic steroid use in weightlifters and bodybuilders: An internet survey of drug utilization. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 15(5), 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipou, A., Castle, D. J., & Rossell, S. L. (2019). Direct comparisons of anorexia nervosa and body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review. Psychiatry Research, 274, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, K. A. (2015). Body dysmorphic disorder: Clinical aspects and relationship to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Focus, 13(2), 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C. G., Pope, H. G., Menard, W., Fay, C., Olivardia, R., & Phillips, K. A. (2005). Clinical features of muscle dysmorphia among males with body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image, 2(4), 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, H., Phillips, K. A., & Olivardia, R. (2000). The Adonis complex: The secret crisis of male body obsession. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, H. G., Jr., Gruber, A. J., Choi, P., Olivardia, R., & Phillips, K. A. (1997). Muscle dysmorphia: An underrecognized form of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics, 38(6), 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, R. M. A. D., & Hauck Filho, N. (2025). Taxometric evidence for the dimensional structure of body dysmorphic disorder and muscle dysmorphia. Current Psychology, 44(10), 9358–9364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohman, L. (2009). The relationship between anabolic androgenic steroids and muscle dysmorphia: A review. Eating Disorders, 17(3), 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Aparicio, M., Badenes-Ribera, L., Sanchez-Meca, J., Fabris, M. A., & Longobardi, C. (2020). A reliability generalization meta-analysis of self-report measures of muscle dysmorphia. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 27(1), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rück, C., Mataix-Cols, D., Feusner, J. D., Shavitt, R. G., Veale, D., Krebs, G., & Fernández de la Cruz, L. (2024). Body dysmorphic disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 10(1), 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarth, M., Westlye, L. T., Havnes, I. A., & Bjørnebekk, A. (2023). Investigating anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence and muscle dysmorphia with network analysis among male weightlifters. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, K., & Hausenblas, H. A. (2015). The truth about exercise addiction: Understanding the dark side of thinspiration. Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Segura-García, C., Ammendolia, A., Procopio, L., Papaianni, M. C., Sinopoli, F., Bianco, C., De Fazio, P., & Capranica, L. (2010). Body uneasiness, eating disorders, and muscle dysmorphia in individuals who overexercise. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(11), 3098–3104. [Google Scholar]

- Settanni, M., Quilghini, F., Toscano, A., & Marengo, D. (2025). Assessing the accuracy and consistency of large language models in triaging social media posts for psychological distress. Psychiatry Research, 351, 116583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specter, S. E., & Wiss, D. A. (2014). Muscle dysmorphia: Where body image obsession, compulsive exercise, disordered eating, and substance abuse intersect in susceptible males. In Eating disorders, addictions and substance use disorders: Research, clinical and treatment perspectives (pp. 439–457). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanberg, P., & Atar, D. (2009). Androgenic anabolic steroid abuse and the cardiovascular system. Doping in Sports: Biochemical Principles, Effects and Analysis, 195, 411–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliu, O. (2023). At the crossroads between eating disorders and body dysmorphic disorders—The case of bigorexia nervosa. Brain Sciences, 13(9), 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D. C., & Murray, A. D. (2012). Body image behaviors: Checking, fixing, and avoiding. Encyclopedia of Body Image and Human Appearance, 1, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A., & Szabo, A. (2023). Exercise addiction: A narrative overview of research issues. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 25(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (Year) | Sample (Population) | Key Measures | AAS/PED Use Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scarth et al. (2023) | N = 241 male weightlifters (153 AAS users, 88 controls); mean age ~34 | MD symptoms (Muscle Dysmorphia Inventory, MDI); clinical interview for AAS dependence (SCID) | Group: current/past AAS users vs. non-users |

| Cerea et al. (2018) | N = 125 male recreational lifters (42 bodybuilders, 61 strength athletes, 22 fitness practitioners); mean age ~30 | MD symptoms (MDDI); self-esteem (RSES); perfectionism (MPS); orthorexia (ORTO-15); social anxiety (Social Phobia Scale) | Self-reported AAS use and considering AAS use |

| MacPhail and Oberle (2022) | N = 1601 weightlifters (555 bodybuilders, 889 powerlifters, 157 controls; 78% male); mean age 28 | MD symptoms (MDDI); orthorexia (ONI); depression (PHQ-9); OC tendencies (Y-BOCS) | Self-reported steroid use (subgrouped into steroid users vs. non-users within each athlete group) |

| Gunnarsson et al. (2022) | N = 3029 physically active adults (63.8% male); ages 15–65 (54% 25–39) | Exercise addiction (EAI); psychiatric diagnoses (self-reported OCD, social phobia, etc.) | Self-reported AAS use in past year (37 users vs. ~2992 non-users) |

| Ganson et al. (2025b) | N = 1488 general population boys and men in US/Canada; ages 15–35 | Probable MD diagnosis (DSM-5 criteria; MDDI cut-off ≥40); muscularity-oriented behaviors (e.g., drive for muscularity scale) | Self-reported PED use (collected as part of MD criteria; e.g., steroid use for physique) |

| Relationship | Effect Size (95% CI) | Statistic (Significance) | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD severity ↔ OC symptom severity(continuous) | r ≈ 0.24 (0.20–0.28) | Pearson r (p < 0.01) **—moderate positive correlation | MacPhail and Oberle (2022) (MDDI vs. Y-BOCS scores) |

| MD presence ↔ AAS use (binary) | OR ≈ 25–30 (high heterogeneity) | OR (p < 0.001)—markedly higher MD prevalence among steroid users vs. non-users | Kutscher et al. (2024): 58% of AAS-using GBQ men met MD criteria vs. ~2–6% in general male samples |

| MD symptom level—AAS users vs. non-users | d ≈ 0.7 (large); ~0.2 (small) | Cohen’s d (p < 0.001 in serious lifters; p = 0.015 in mixed sample)—steroid users report higher MD symptoms | Scarth et al. (2023): All MD subscale means higher in AAS users (e.g., size/symmetry concerns d~0.8). MacPhail and Oberle (2022): small but significant user vs. non-user difference (η2 = 0.004). |

| OC symptom level—AAS users vs. non-users | d ≈ 0.3 (small) | Cohen’s d (p < 0.001)—steroid users report higher OCD trait scores | MacPhail and Oberle (2022): Y-BOCS scores mean ± SD ≈ 11.9 ± 6.2 (users) vs. 8.5 ± 5.7 (non-users), p < 0.001. |

| Exercise addiction risk ↔ OCD diagnosis | OR = 2.82 (1.18–6.73) | OR (p = 0.019; n.s. after Bonferroni correction)—OCD 3× more likely in those at risk of exercise addiction | Gunnarsson et al. (2022) (11% of sample “at-risk” for exercise addiction had 3% OCD vs. 1% in others). |

| Moderator/Subgroup | Effect on MD–OCD–AAS Relationships | Source/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Athlete type (Bodybuilder vs. others) | MD scores differed by athlete type: bodybuilders > strength athletes ≈ fitness practitioners. Bodybuilders also more likely to consider AAS use (23.8%) than others (≤6%). | Cerea et al. (2018)—Group (training goal) moderated MD severity and steroid inclination. Bigorexia traits strongest in aesthetic-focused lifters. |

| Steroid user vs. non-user status | Among non-users, athlete group differences in MD and OC symptoms were significant (BB/PL > controls). Among AAS users, no significant group differences—all had elevated MD/OC (interaction p < 0.001). Steroid use thus “raises” MD to high levels regardless of group. | MacPhail and Oberle (2022)—Significant sport×steroid use interaction for MD symptoms. Also found depression scores–steroid effect seen in BB/PL but not controls (group × steroid p < 0.01). |

| Gender/Sexual orientation | No significant differences in MD prevalence by gender or orientation in community samples (inclusive of men, few women). However, in gay/bisexual men, AAS use was tied to unique body-image motives (community norms) and high MD co-occurrence (58%). | Ganson et al. (2025a)—inclusive sample, found MD across demographics similarly. Kutscher et al. (2024)—GBQ male sample only; suggests sexuality context may influence why MD/AAS occur (qualitative differences). |

| MD phenotype (lean-focused vs. bulk) | Participants preoccupied with leanness (vs. size) may use AAS more cautiously. Some MD individuals cycled cutting/bulking phases; willingness to use substances (e.g., bulking steroids) varied with phase and phenotype. Those viewing muscular size as top priority were more willing to risk health (and use AAS) to achieve it. | Martenstyn et al. (2022a)—Identified “muscular/lean” vs. “muscular-only” MD subtypes. Quantitative data on phenotype moderation not provided, but qualitative results imply differing propensity for AAS use and compulsive behaviors by subtype. |

| BMI and build | MD cases had lower BMI than non-cases on average (MD group mean BMI ~24 vs. 26, p < 0.01). Men with a larger body fat history were less comfortable bulking (gaining weight) and more prone to MD distress when gaining fat. | Ganson et al. (2025b)—BMI difference suggests MD not simply in high-BMI muscular men. Martenstyn et al. (2022b)—Past body type moderated cutting/bulking experiences (ex-fat individuals struggled with bulking). |

| Study (Year) | Design | Sample | Country | Methodology | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kutscher et al. (2024) | Qualitative, thematic analysis | N = 12 cisgender gay/bisexual men using AAS | USA | Semi-structured interviews + MDDI screen | Motivations for AAS use, health care access, MD symptoms |

| Börjesson et al. (2021) | Qualitative, interpretative | N = 12 female AAS users with long-term gym engagement | Sweden | In-depth interviews | Gender, muscularity, side effects, identity tension |

| Calzolari (2023) | Phenomenological thematic study | N = 30 female bodybuilders with AAS/IPED use | Italy | Semi-structured interviews | Empowerment, identity, bodily control, feminine ideals |

| Izzat et al. (2023) | Grounded theory | N = 20 male AAS users (18–40 y), 10+ gym hours/week | Middle East | Focus groups + individual interviews | Beliefs around steroids, health risk perception, motivation |

| Martenstyn et al. (2022a) | Interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) | N = 29 men with diagnosed muscle dysmorphia | Australia | In-depth clinical interviews | MD symptomatology, identity, subtype profiles |

| Theme | Description | Illustrative Quotes (Participant) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Body Image Ideals and Dissatisfaction | Unattainable muscular ideals drive constant dissatisfaction. Individuals with MD fixate on “not being big/lean enough” despite already above-average musculature. Goals become moving goalposts—whenever one target is met, a new flaw is found. Many compare themselves to idealized bodies (e.g., social media or competition images), fueling a chronic sense of inadequacy. | “Unsatisfied, there’s a lot more I could do. I need to put on more muscle… I’m lacking where I want to be.” (Diagnosed MD) “Our aim was the perfect physique with all the muscles in harmony… one felt her shoulders weren’t good enough… then perhaps her legs were wrong. All the time, the aim was the perfect physique.” (Female bodybuilder) |

| 2. Compulsivity and Rigid Routines | Compulsive exercise and dieting routines dominate daily life. Individuals report meticulous tracking of workouts, calories, and macros, and feel severe anxiety if routines are disrupted. Behaviors like mirror checking multiple times a day, body checking with tape measures or photos, and refusing to deviate from meal plans are common. These rigid behaviors resemble OCD rituals and are used to manage the anxiety about physique. Social or leisure activities are often sacrificed to prioritize training (“living in a bubble”). | “I pass up chances to meet new people because of my workout schedule” (common sentiment; MD Functional Impairment). “I had cheated by eating four grapes two weeks before the competition… I felt it was cheating and came second. I kept thinking: would I have won if I hadn’t eaten those grapes? … I was so scared of anything that could sabotage my diet or commitment, because it meant my whole life to me.” (Female bodybuilder). “I became aggressive with my family and friends, so I avoided everyone and stayed alone… over that period.” (Male steroid user describing how obsessive regimen caused social withdrawal). |

| 3. Masculinity, Femininity and Identity | Muscularity is tied to gender identity and self-esteem. Men often equate bigger muscles with greater masculinity, sometimes to counter feelings of inferiority (e.g., some gay men felt pressure to achieve the “ideal male physique” to be desirable). Women using AAS struggle with femininity, walking a tightrope between gaining muscle and keeping an “acceptable” female appearance. Participants concealed their bodies due to fear of judgment (e.g., being seen as too masculine) and integrated the muscular ideal deeply into their identity. | “For men, it’s like the bigger I am, the more confident and masculine I feel—it became my whole identity.” (Male MD sufferer, implied). “When my body got muscles, they laughed and said the men’s department is across the street… If I wear a dress, people look at me like I’m a transvestite. I constantly had to prove I’m a girl… I had to fight all the time.” (Female AAS user on social reactions). “Almost all [with MD] avoided taking their shirt off in public…fear of being judged as inadequate.” (Diagnosed MD participants). |

| 4. Motivations for AAS/PED Use | Why they use steroids/PEDs: The primary drivers are achieving the ideal physique and competitive success. Many start AAS to break past natural limits when muscle gains plateau (“when my body could no longer develop naturally, I felt careful use of AAS was justified”). The desire to win in bodybuilding or to be admired for one’s body is a strong motivator. Some also cite professional pressure (e.g., being a personal trainer) or community norms. Notably, users often continue AAS despite side effects, prioritizing physique over health. | “The desire to compete in bodybuilding contests was my main motivation to use steroids.” (Male bodybuilder, Jordan). “I would be lying if I said I wanted to stop taking steroids. I’m confident I can’t maintain this shape with only normal exercise and food… I will take steroids as long as there are competitions.” (Male AAS user with MD). “For us, bodybuilding was empowerment—the more we trained, the more confidence we gained. Some started using IPEDs to enhance their agency further.” (Female bodybuilders, Italy). |

| 5. Perceived Harms, Help-Seeking and Mental Health | Awareness of risks vs. willingness to seek help: Many users acknowledge steroids carry health risks (“Nobody can claim that steroids are safe… they are completely unsafe” said one coach). They experience side effects like mood swings, acne, or depression—e.g., aggression and social isolation (see Theme 2) or body-image “crashes” when off-cycle. However, most downplay these effects as temporary or manageable, using strategies like cycling, “post-cycle therapy,” or ancillary drugs to mitigate harm. Help-seeking is limited: participants often do not trust healthcare providers with their steroid use. They felt doctors “just tell you to stop” and lack understanding of bodybuilding goals. Some found no specialist to consult and instead relied on bro-science or online forums. This leads to a culture of self-directed harm reduction rather than formal treatment. | “These symptoms had no effect on my quality of life… they’re temporary and disappear after the cycle.” (Male AAS user dismissing side effects). “I tried to live with the side effects because I know they’re temporary… acne still bothers me but I’ll see a dermatologist.” (Male user on coping, age 22). “I don’t seek information from doctors because they’re against the idea… they have knowledge but want to stay out of it to protect themselves… We don’t have a medical specialist here to go to. I actually have to follow up with a doctor in America, who specializes in steroid use for athletes.” (Multiple male AAS users). “Despite terrible symptoms… I made an excellent decision: I stopped using steroids… the right method to get rid of the hormone circle and its effects.” (One user who quit, minority viewpoint). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Çınaroğlu, M.; Yılmazer, E. Muscle Dysmorphia, Obsessive–Compulsive Traits, and Anabolic Steroid Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091206

Çınaroğlu M, Yılmazer E. Muscle Dysmorphia, Obsessive–Compulsive Traits, and Anabolic Steroid Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091206

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇınaroğlu, Metin, and Eda Yılmazer. 2025. "Muscle Dysmorphia, Obsessive–Compulsive Traits, and Anabolic Steroid Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091206

APA StyleÇınaroğlu, M., & Yılmazer, E. (2025). Muscle Dysmorphia, Obsessive–Compulsive Traits, and Anabolic Steroid Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091206