The Link Between Mate Value Discrepancy and Relationship Satisfaction—An Empirical Examination Using Response Surface Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

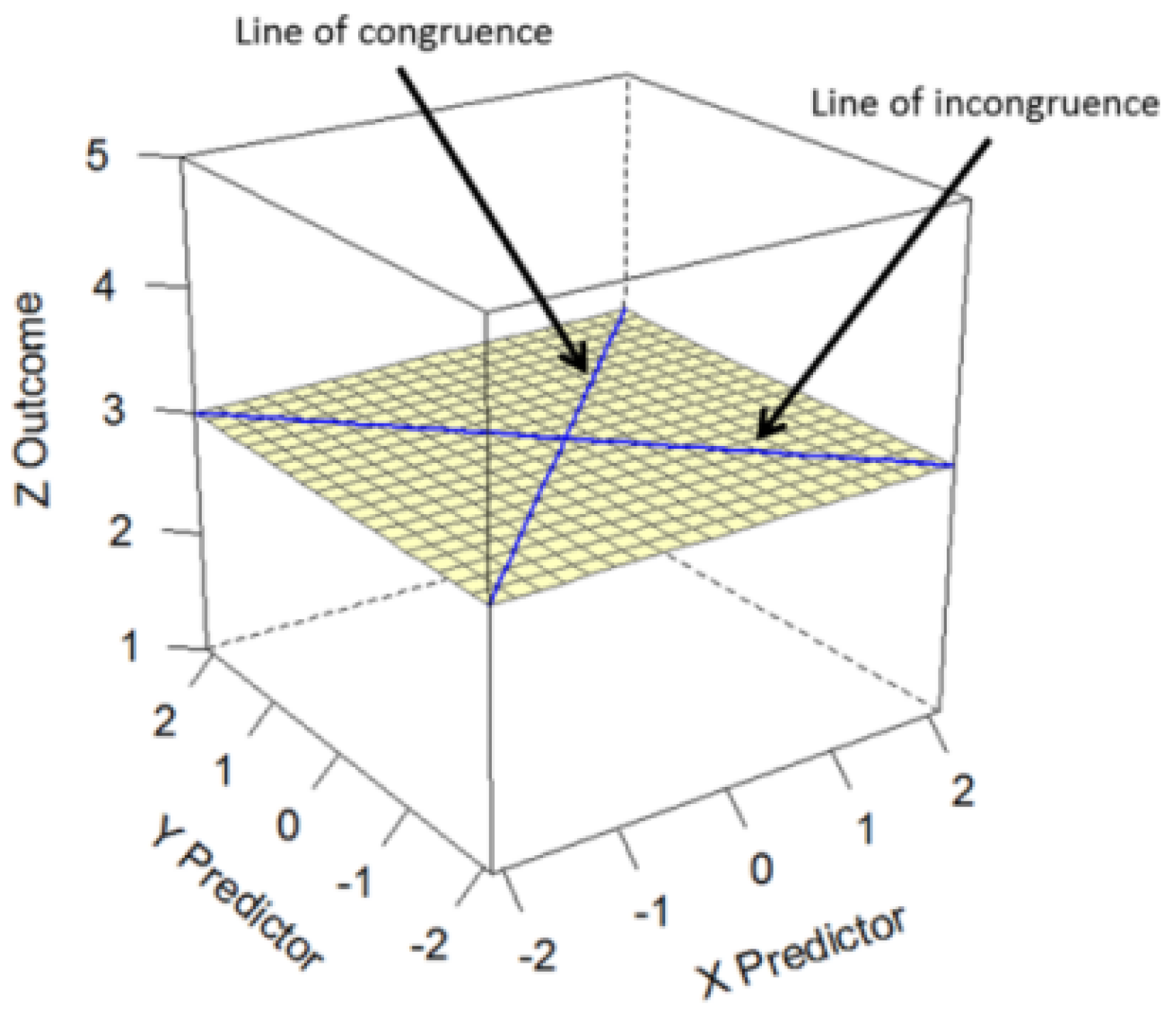

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Measurement Part

2.3.2. Structural Part

3. Results and Findings

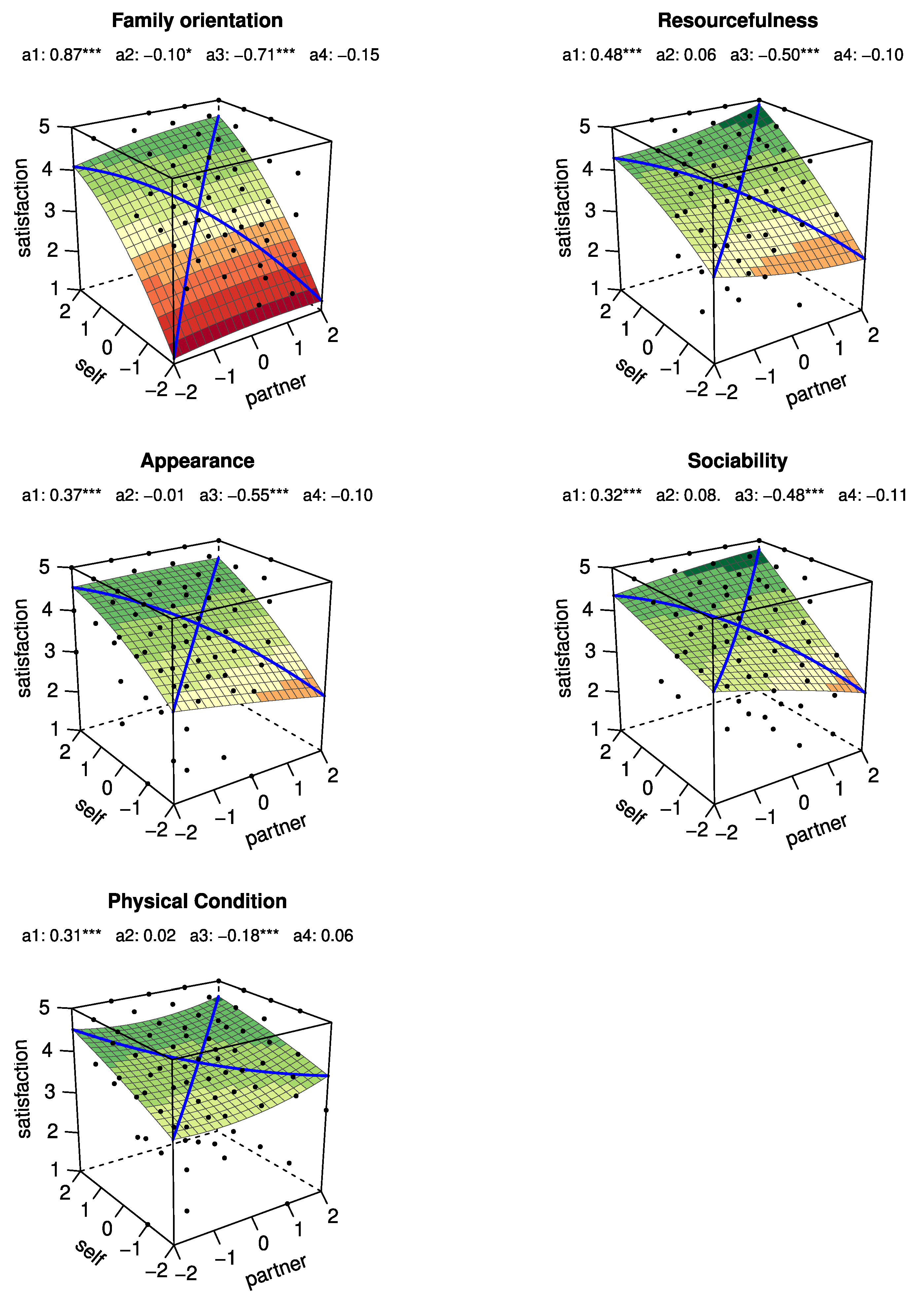

3.1. Family Orientation

3.2. Resourcefulness

3.3. Appearance

3.4. Sociability

3.5. Physical Condition

3.6. Combined Overview

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barranti, M., Carlson, E. N., & Côté, S. (2017). How to test questions about similarity in personality and social psychology research: Description and empirical demonstration of response surface analysis. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhogal, M. S., Rhead, C., & Tudor, C. (2019). Understanding digital dating abuse from an evolutionary perspective: Further evidence for the role of mate value discrepancy. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D. M., Goetz, C., Duntley, J. D., Asao, K., & Conroy-Beam, D. (2017). The mate switching hypothesis. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukcan-Tetik, A., Campbell, L., Finkenauer, C., Karremans, J. C., & Kappen, G. (2017). Ideal standards, acceptance, and relationship satisfaction: Latitudes of differential effects. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy-Beam, D., Goetz, C. D., & Buss, D. M. (2016). What predicts romantic relationship satisfaction and mate retention intensity: Mate preference fulfillment or mate value discrepancies? Evolution and Human Behavior, 37(6), 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danel, D. P., Siennicka, A., Glińska, K., Fedurek, P., Nowak-Szczepańska, N., Jankowska, E. A., & Lewandowski, Z. (2017). Female perception of a partner’s mate value discrepancy and controlling behaviour in romantic relationships. Acta Ethologica, 20(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyuris, P., Járai, R., & Bereczkei, T. (2010). The effect of childhood experiences on mate choice in personality traits: Homogamy and sexual imprinting. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(5), 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrick, S. S. (1988). A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50(1), 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howie, J. M., & Pomiankowski, A. (2021). Mate value. In V. A. Weekes-Shackelford, & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science (pp. 4893–4901). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. D., Galambos, N. L., & Anderson, J. R. (2016). Skip the dishes? Not so fast! Sex and housework revisited. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(2), 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsner, B. R., Figueredo, A. J., & Jacobs, W. J. (2003). Self, friends, and lovers: Structural relations among beck depression inventory scores and perceived mate values. Journal of Affective Disorders, 75(2), 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mare, R. D. (2016). Educational homogamy in two gilded ages: Evidence from intergenerational social mobility data. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 663(1), 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäenpää, E., & Jalovaara, M. (2013). The effects of homogamy in socio-economic background and education on the transition from cohabitation to marriage. Acta Sociologica, 56(3), 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, M., & Määttänen, I. (2020). Norwegian men and women value similar mate traits in short-term relationships. Evolutionary Psychology, 18(4), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, M., Määttänen, I., & Mittner, M. (2024). Testing sexual strategy theory in norway. Behavioral Sciences, 14, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacht, R., & Kramer, K. L. (2019). Are we monogamous? A review of the evolution of pair-bonding in humans and its contemporary variation cross-culturally. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönbrodt, F. D., & Humberg, S. (2023). RSA: An r package for response surface analysis (version 0.10.6). Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=RSA (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Shanock, L. R., Baran, B. E., Gentry, W. A., Pattison, S. C., & Heggestad, E. D. (2010). Polynomial regression with response surface analysis: A powerful approach for examining moderation and overcoming limitations of difference scores. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(4), 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidelinger, R. J., & Booth-Butterfield, M. (2007). Mate value discrepancy as predictor of forgiveness and jealousy in romantic relationships. Communication Quarterly, 55(2), 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Bhogal, M. S., & Howman, J. M. (2019). Mate value discrepancy and attachment anxiety predict the perpetration of digital dating abuse. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 5, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starratt, V. G., Weekes-Shackelford, V. A., & Shackelford, T. K. (2017). Mate value both positively and negatively predicts intentions to commit an infidelity. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štěrbová, Z., Třebický, V., Havlíček, J., Tureček, P., Correa Varella, M. A., & Varella Valentova, J. (2018). Father’s physique influences mate preferences but not the actual choice of male somatotype in heterosexual women and homosexual men. Evolution and Human Behavior, 39, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štěrbová, Z., Tureček, P., & Kleisner, K. (2019). Consistency of mate choice in eye and hair colour: Testing possible mechanisms. Evolution and Human Behavior, 40, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Regional Health–Europe. (2025). The paradox of prosperity and poverty: Confronting inequality in norway. The Lancet Regional Health-Europe, 49, 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiessen, D., & Gregg, B. (1980). Human assortative mating and genetic equilibrium: An evolutionary perspective. Ethology and Sociobiology, 1(2), 111–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Ma, C. (2025). Educational assortative mating and its impact on marital quality in china. Journal of Family Issues, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, G., Zeigler-Hill, V., & Ross, J. (2024). Mate value discrepancies and mate retention behaviors: A cubic response surface analysis. Personal Relationships, 31(3), 676–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Level | Count | Percent | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age | 904 | 51.87 | 15.76 | 18 | 86 | ||

| Relationship length | <3 months | 1 | 0.1 | ||||

| 3–6 months | 1 | 0.1 | |||||

| 6–12 month | 8 | 0.9 | |||||

| 1–2 years | 20 | 2.2 | |||||

| 2–4 years | 64 | 7.1 | |||||

| 4–6 years | 53 | 5.9 | |||||

| 6–10 years | 75 | 8.3 | |||||

| 10–20 years | 207 | 22.9 | |||||

| >20 years | 475 | 52.5 | |||||

| gender | men | 488 | 54 | ||||

| women | 416 | 46 | |||||

| Number of children under 18 | none | 622 | 68.8 | ||||

| 1 kid | 92 | 10.2 | |||||

| 2 kids | 128 | 14.2 | |||||

| 3 kids | 51 | 5.6 | |||||

| 4 kids | 9 | 1 | |||||

| >5 kids | 1 | 0.1 | |||||

| do not want to answer | 1 | 0.1 | |||||

| Educational level | Secondary | 36 | 4 | ||||

| High School | 261 | 28.9 | |||||

| University 1–3 yrs | 302 | 33.4 | |||||

| University 4 yrs + | 224 | 24.8 | |||||

| University 5 yrs + | 56 | 6.2 | |||||

| Other | 25 | 2.8 |

| Latent Variable | Label | M | SE | Z | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| family orientation partner (Famp) | Understanding | 3.93 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 57.93 | 0.86 |

| Kind | 4.25 | 0.84 | 0.01 | 70.78 | ||

| Loyal | 4.29 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 57.47 | ||

| Caring | 4.22 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 66.85 | ||

| Family man/woman | 4.14 | 0.67 | 0.02 | 34.76 | ||

| resourcefulness partner (Resp) | Independent | 3.80 | 0.56 | 0.02 | 22.55 | 0.81 |

| Intelligent | 4.00 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 36.24 | ||

| Successful | 3.71 | 0.84 | 0.01 | 69.07 | ||

| Looked up to | 3.69 | 0.77 | 0.02 | 50.14 | ||

| Has or likely to have good finance | 3.63 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 30.57 | ||

| Resourceful person | 3.91 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 56.92 | ||

| appearance partner (Appp) | Attractive face | 3.82 | 0.79 | 0.02 | 52.50 | 0.86 |

| Attractive body | 3.50 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 74.69 | ||

| Sexy | 3.39 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 75.47 | ||

| sociability partner (Socp) | Humorous | 3.56 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 56.98 | 0.81 |

| Social intelligent | 3.83 | 0.68 | 0.02 | 32.75 | ||

| Outgoing | 3.69 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 27.55 | ||

| Makes others laugh | 3.54 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 56.37 | ||

| physical condition partner (Phyp) | Healthy | 3.61 | 0.79 | 0.02 | 37.81 | 0.68 |

| In good physical condition | 3.29 | 0.75 | 0.02 | 34.81 | ||

| family orientation nself (Fams) | Understanding | 3.96 | 0.78 | 0.02 | 47.43 | 0.84 |

| Kind | 4.12 | 0.79 | 0.02 | 48.93 | ||

| Loyal | 4.27 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 38.71 | ||

| Caring | 4.15 | 0.78 | 0.02 | 48.33 | ||

| Family man/woman | 4.00 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 19.99 | ||

| resourcefulness self (Ress) | Independent | 3.84 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 18.64 | 0.82 |

| Intelligent | 3.82 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 27.45 | ||

| Successful | 3.41 | 0.79 | 0.02 | 48.98 | ||

| Looked up to | 3.14 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 35.77 | ||

| Has or likely to have good finance | 3.48 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 25.27 | ||

| Resourceful person | 3.79 | 0.75 | 0.02 | 42.60 | ||

| appearance self (Apps) | Attractive face | 3.01 | 0.76 | 0.02 | 43.68 | 0.85 |

| Attractive body | 2.73 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 55.52 | ||

| Sexy | 2.44 | 0.82 | 0.02 | 53.76 | ||

| sociability self (Socs) | Humorous | 3.32 | 0.82 | 0.02 | 52.87 | 0.81 |

| Social intelligent | 3.64 | 0.61 | 0.02 | 25.68 | ||

| Outgoing | 3.45 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 23.69 | ||

| Makes others laugh | 3.42 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 61.64 | ||

| physical condition self (Phys) | Healthy | 3.64 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 27.31 | 0.69 |

| In good physical condition | 3.19 | 0.75 | 0.03 | 29.95 | ||

| relationship satisfaction (Rsat) | Your partner meets your needs | 4.04 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 102.05 | 0.89 |

| You are satisfied with your relationship | 4.20 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 143.85 | ||

| Your relationship is good compared to most | 4.12 | 0.84 | 0.01 | 77.32 | ||

| You think that you should not have gotten into this relationship (reversed) | 4.33 | 0.61 | 0.02 | 28.28 | ||

| Your relationship has met your original expectations | 3.77 | 0.64 | 0.02 | 30.47 | ||

| You love your partner | 4.38 | 0.77 | 0.01 | 53.52 | ||

| You have problems in your relationship (reversed) | 3.65 | 0.54 | 0.02 | 21.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mehmetoglu, M.; Määttänen, I.; Mittner, M. The Link Between Mate Value Discrepancy and Relationship Satisfaction—An Empirical Examination Using Response Surface Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081131

Mehmetoglu M, Määttänen I, Mittner M. The Link Between Mate Value Discrepancy and Relationship Satisfaction—An Empirical Examination Using Response Surface Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081131

Chicago/Turabian StyleMehmetoglu, Mehmet, Ilmari Määttänen, and Matthias Mittner. 2025. "The Link Between Mate Value Discrepancy and Relationship Satisfaction—An Empirical Examination Using Response Surface Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081131

APA StyleMehmetoglu, M., Määttänen, I., & Mittner, M. (2025). The Link Between Mate Value Discrepancy and Relationship Satisfaction—An Empirical Examination Using Response Surface Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081131