2.1. Job Demands–Resources Model

The Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model of

Demerouti et al. (

2001) served as the theoretical model for this study. The JD-R model differentiates between job demands and job resources. Job demands represent physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained effort, such as an unfavorable work environment, and are associated with job strain (health impairment process). Job resources represent functional physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job, such as autonomy or feedback. According to the JD-R model, job resources can stimulate personal development and lead to high work engagement (motivational process) (

Bakker & Demerouti, 2007;

Demerouti et al., 2019). The JD-R model was later expanded by personal resources (

Xanthopoulou et al., 2007), which can be defined as “aspects of the self that are generally linked to resiliency” (

Hobfoll et al., 2003, p. 632). They contribute to explaining motivational outcomes and, therefore, play a similar role as job resources (

Demerouti et al., 2019). This study focused on job demands and resources regarding social relationships, personal resources, and especially the motivational process of the JD-R model.

In the specific context of public administration, characterized by hierarchical structures, formalized communication channels, and institutional constraints, the JD-R model offers a robust framework for examining how these unique organizational features shape the interplay between demands, resources, and employee engagement. The evolving nature of work towards hybrid arrangements introduces novel challenges and opportunities for both job and personal resources, making this theoretical lens particularly relevant.

2.2. Job Demands and Resources Regarding Social Relationships in the Context of Remote and Hybrid Work

Although literature shows a greater tendency towards a beneficial impact of hybrid and remote work on the well-being of employees, some of the main challenges of these forms of work concern social relationships at work, such as feelings of social isolation (

Charalampous et al., 2019). Studies among employees of public organizations and services described feelings of loneliness, isolation, and disconnection from colleagues with respect to remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic (

Babapour Chafi et al., 2022;

Seinsche et al., 2023b). These challenges may be amplified in public sector contexts due to organizational characteristics such as rigid hierarchies and formal communication practices (

Rainey, 2009), which can limit spontaneous interpersonal interactions compared to private sector settings (

Belzunegui-Eraso & Erro-Garcés, 2020;

B. Wang et al., 2021). Thus, hybrid work in public administration entails unique social demands that warrant targeted investigation.

In addition, concerns related to limited knowledge exchange were expressed (

Babapour Chafi et al., 2022). On the one hand, German public service employees stated that there was more social exchange and interaction, e.g., in the form of small talk, unplanned communication, and passing on information, when working in the office (

Seinsche et al., 2023a,

2023b). On the other hand, employees from geographically distributed teams saw some benefits in remote work in that they felt better cohesion because of the possibilities to meet online and perceived easier collaboration. However, further challenges of remote work were described as receiving limited feedback and difficulties in overcoming the fear of missing out at work (

Babapour Chafi et al., 2022). Establishing relationships, ensuring their quality, and building trust were also more difficult when working from home (

Babapour Chafi et al., 2022;

Seinsche et al., 2023b). Several studies support the findings on difficulties with relationships (

Juchnowicz & Kinowska, 2021;

Knardahl & Christensen, 2022;

Wontorczyk & Rożnowski, 2022). Among remote, hybrid, and on-site workers in southern Poland, hybrid workers assessed their possibilities of promoting positive interpersonal relationships at work as significantly lower than on-site workers (

Wontorczyk & Rożnowski, 2022).

Juchnowicz and Kinowska (

2021) found that remote work significantly limited the perception of supportive relationships with superiors and co-workers in the workplace. This was found for participants who worked exclusively remotely and for hybrid workers, who worked remotely 1–2 days a week. However, no significant effects were observed for those working remotely less than once a week or 3–4 days a week. In contrast,

Knardahl and Christensen (

2022) described a monotonic dose–response relationship between the hours worked at home and co-worker support. The perceived co-worker support decreased steadily as the number of hours worked at home increased.

With regard to the state of research, differences in job demands and resources regarding social relationships between different forms of work can be assumed. In the present study, the amount of face-to-face contact with colleagues in the office (low: once a week or less vs. high: several times a week) served as a proxy for the form of work (on-site, hybrid, remote). In this respect, the following two hypotheses were made.

H1. There is a significant difference in the amount of face-to-face contact with colleagues at the office between employees working predominantly at the office, working hybrid, and working predominantly remotely.

H2. There is a significant difference in the job demand, such as fear of missing out at work (H2a), and in the social resources, such as team cohesion (H2b) and social support (H2c), between employees with low and high face-to-face contact with their colleagues at the office.

2.3. Associations Between Social Resources, Personal Resources, and Work Engagement, as Well as the Moderating Role of Face-to-Face Contact

Work engagement was described as a distinct concept and defined as “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” by

Schaufeli and Bakker (

2004, p. 4). Vigor refers to high levels of energy and mental resilience as well as the willingness to invest effort in one’s work. Dedication means being strongly involved in one’s work and deriving a sense of significance from it. Absorption describes a state of being immersed and happily engrossed in one’s work (

Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). The main predictors of work engagement are job and personal resources (

van den Heuvel et al., 2010).

One job resource that depicts social relationships and collaboration at work is team cohesion. Team cohesion can be understood as “the solidarity or unity of a group” (

Forsyth, 2014, p. 10). Team cohesion highly correlates with concepts of social support at work and a sense of community (

Lieb et al., 2024) and was found to be positively related to job satisfaction (

Bae et al., 2023;

Penconek et al., 2021). To the best of our knowledge, studies on the relationship between team cohesion and work engagement are still pending.

Hybrid work requires new forms of leadership that build on trust in the workforce and empower employees with more personal responsibility (

Quatram & van Kempen, 2021). Empowering leadership is a leadership form that is characterized by the support of subordinates’ autonomy (

Amundsen & Martinsen, 2014). Studies found statistically significant positive relationships between empowering leadership and work engagement (

Forster & Koob, 2023;

Tuckey et al., 2012).

In public administration, where institutional trust and service quality are paramount, social resources such as team cohesion and empowering leadership are critical not only for employee motivation but also for maintaining organizational legitimacy (

Brewer, 2003;

Zubair et al., 2021).

Under hybrid work conditions, these social resources might be disrupted, heightening their significance.

No studies in the field of public administration were identified. Therefore, we examined the following hypothesis.

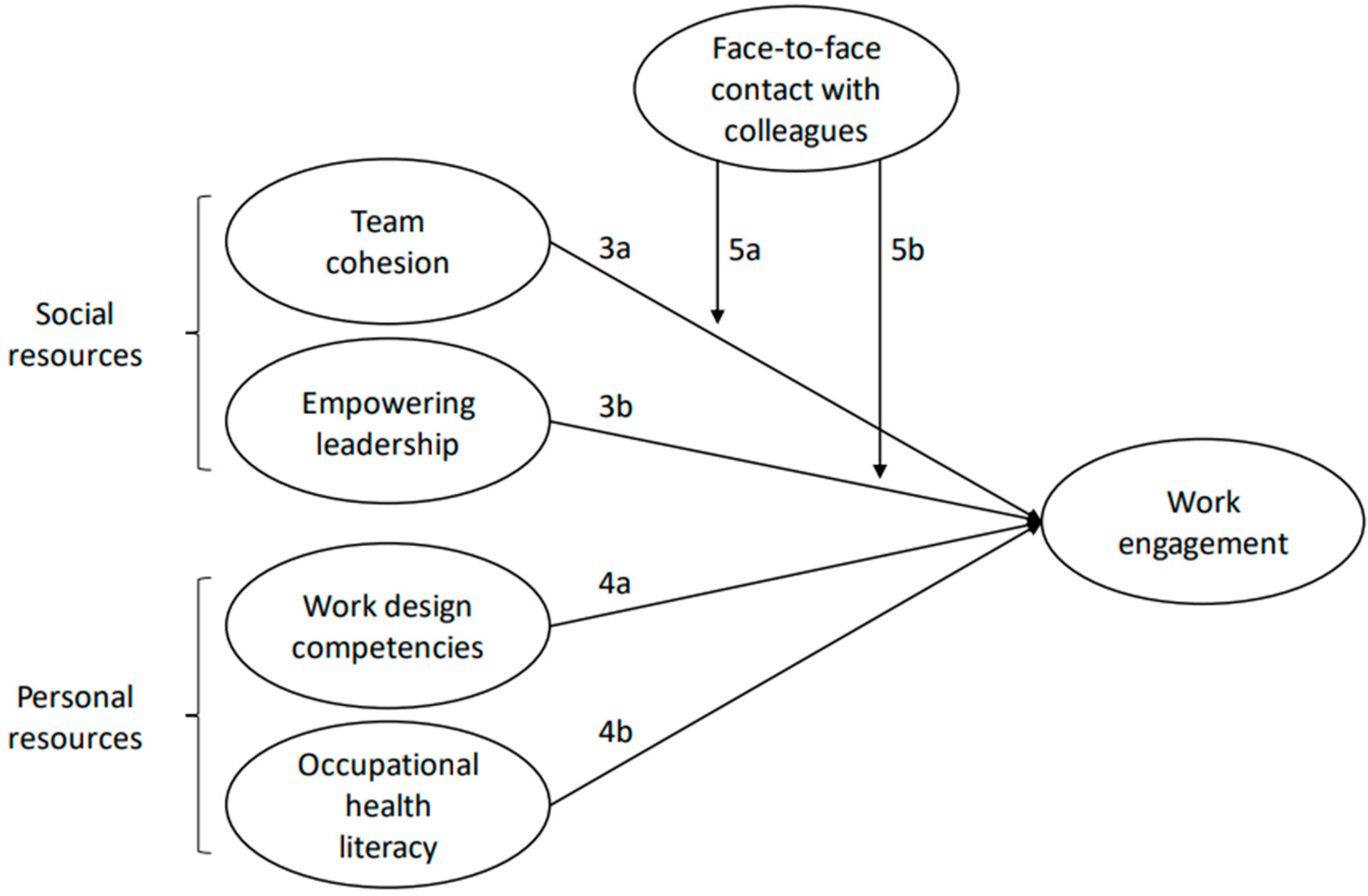

H3. The social resources, such as team cohesion (H3a) and empowering leadership (H3b), are significantly associated with work engagement among employees in public administration.

Working remotely from home places additional demands on employees compared to on-site work, such as high levels of self-discipline, personal responsibility, and self-organization (

Quatram & van Kempen, 2021). Skills that are required to cope with the demands of an independent work organization can be summarized as work design competencies (

Dettmers & Clauß, 2018). They can be defined as “knowledge of how to design favorable working conditions that enable effective management of one’s own work tasks, while at the same time promoting motivation and reducing stress” (

Dettmers & Clauß, 2018, p. 17). In former studies, work design competencies showed first significant positive relationships with work engagement (

Dettmers & Clauß, 2018) and appeared to be relevant to work ability, which indicates employees’ current and future ability to work (

Niebuhr et al., 2022).

Another individual competence of employees in the context of working life comprises occupational health literacy (OHL) (

Ehmann et al., 2021). The concept of OHL includes the aspects of accessing, understanding, appraising, and applying health information with regard to safety and health at work (

Ehmann et al., 2021;

Jørgensen & Larsen, 2019;

Rauscher & Myers, 2014). In a recent study, knowledge-/skill-based OHL was positively associated with work ability among participants in diverse small and medium-sized enterprises (

Friedrich et al., 2024). However, to the best of our knowledge, research on OHL is still sparse. Individual competencies to manage one’s own health could be important personal resources, especially in new hybrid work contexts where employees are left to their own devices to a certain extent (

Ehmann et al., 2021). Therefore, the following hypothesis was examined in this study.

H4. The personal resources, such as work design competencies (H4a) and OHL (H4b), are significantly associated with work engagement among employees in public administration.

Previous research has shown that predictors of work engagement and well-being differ depending on work arrangement (remote, hybrid, or on-site) (

Grobelny, 2023;

Wontorczyk & Rożnowski, 2022). For instance, positive interpersonal relations predicted engagement more strongly among remote workers, while supportive leadership showed stronger associations for on-site employees (

Wontorczyk & Rożnowski, 2022).

Grobelny (

2023) highlighted that the relationship between job resources and well-being varies across different team settings and suggested extending the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model by including team type as a contextual factor.

From a theoretical perspective, face-to-face interaction enhances social presence, mutual trust, and spontaneous informal exchange, which are crucial for the effective functioning of social resources like team cohesion and leadership [e.g., Social Presence Theory, Media Richness Theory]. In physical work environments, social cues such as body language, tone of voice, and informal encounters are more salient, enabling stronger interpersonal bonds. Thus, face-to-face contact can be expected to amplify the effects of social resources on employee engagement.

Given the formalized and hierarchical structure of public sector organizations (

Rainey, 2009), face-to-face interaction may play a particularly important role in maintaining social resources such as team cohesion and leadership support. As a result, the positive effects of these resources on employee engagement may be more pronounced in the public sector than in less formal organizational contexts.

Based on these theoretical and empirical considerations, we formulated the following hypothesis:

H5. Face-to-face contact with colleagues significantly moderates the relationship between the social resources, such as team cohesion (H5a) and empowering leadership (H5b) and work engagement.

In contrast to social resources, personal resources such as work design competencies are internal, self-regulatory capacities that enable individuals to actively shape their work environment and maintain motivation and engagement, regardless of external conditions. According to the JD-R model, personal resources function as relatively stable individual characteristics that are not bound to situational factors like physical proximity to colleagues.

Moreover, personal resources rely less on interpersonal interaction and more on individual agency, problem-solving, and proactive behavior. These qualities can be deployed both in remote and in on-site work contexts. Thus, the positive relationship between personal resources and work engagement is expected to remain stable, independent of face-to-face work conditions.

Consequently, the relationship between personal resources and engagement is expected to be stable and not moderated by face-to-face contact.

Figure 1 visually summarizes the hypotheses H3-H5 on the associations between social and personal resources and work engagement and the moderation effects of face-to-face contact.