Can Gratitude Ease the Burden of Fibromyalgia? A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

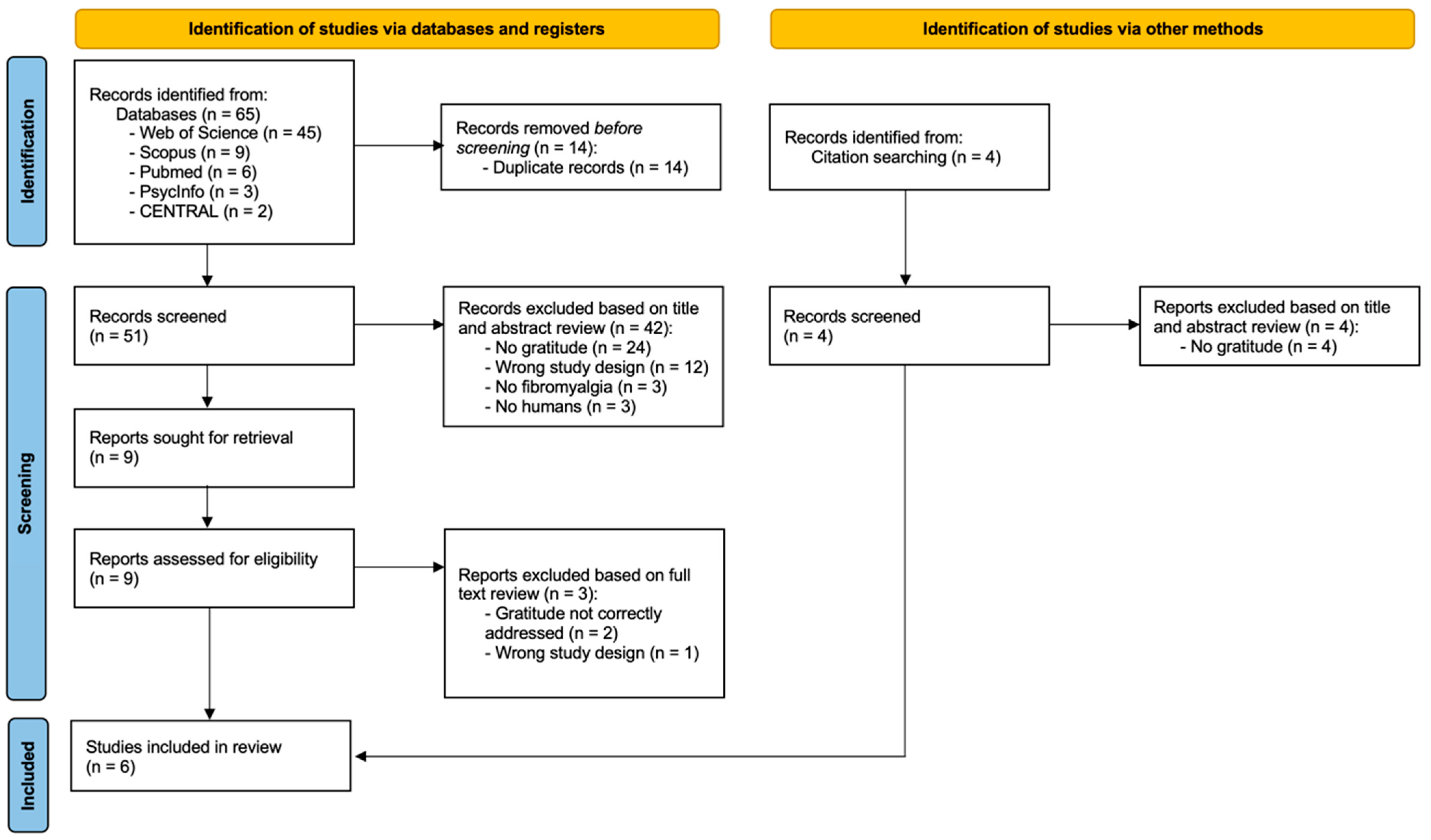

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Summary of Key Findings

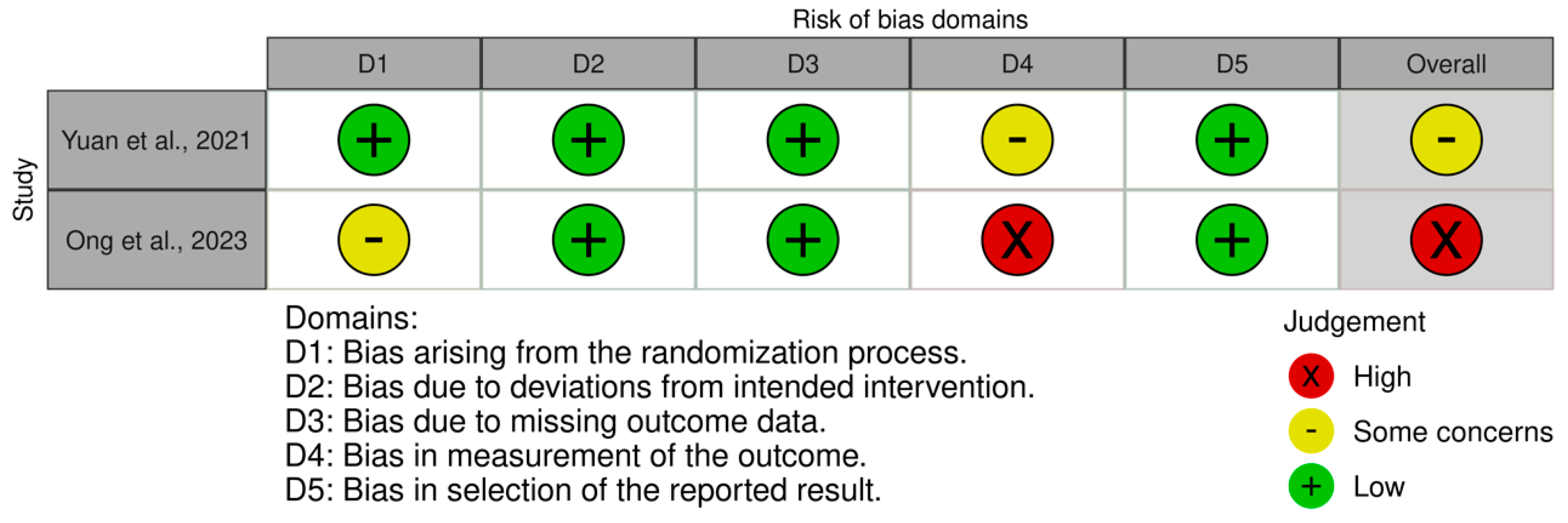

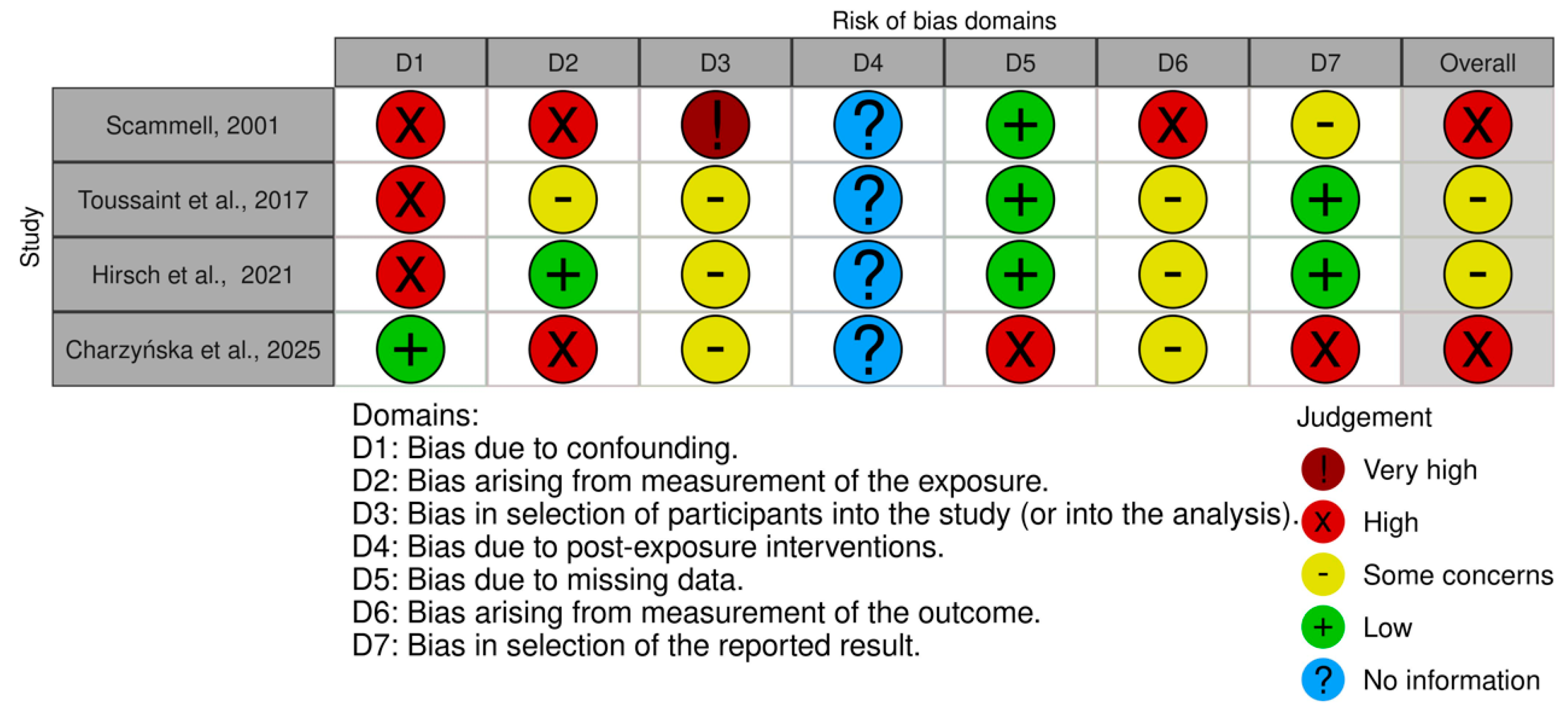

3.3. Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAPT | ACTTION-APS Pain Taxonomy |

| ACTTION | Addiction Clinical Trial Translations Innovations Opportunities and Networks |

| ACR | American College of Rheumatology |

| APS | American Pain Society |

| CBT | Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy |

| CENTRAL | Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials |

| EQ-5D | Euroqol Five Dimensions |

| FM | Fibromyalgia |

| FAS | Fibromyalgia Assessment Status |

| FIQ | Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire |

| FIQR | Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire |

| FSC | Fibromyalgia Survey Criteria |

| GADS | Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale |

| GF | General Fatigue Subscale |

| GFPA | German Fibromyalgia Patient Association |

| GQ6 | Gratitude Questionnaire 6 |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| HAQ | Health Assessment Questionnaire |

| LARKSPUR | Lessons in Affect Regulation to Keep Stress and Pain Under Control |

| mDES | Modified Differential Emotions Scale |

| PCS | Pain Catastrophizing Scale |

| PHQ2 | Patient Health Questionnaire 2 |

| PHQ4 | Patient Health Questionnaire 4 |

| PHQ15 | Patient Health Questionnaire 15 |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROMIS F-SF | Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System Fatigue—Short Form |

| PROMIS-PF | Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System—Physical Function |

| PROMIS-PI | Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System—Pain Interference |

| PROMIS-SI | Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System—Pain Intensity |

| PROSPERO | The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| PSS4 | Perceived Stress Scale 4 |

| QoLS | Quality of Life Scale |

| RASCAS | Revised Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale |

| RCT | Controlled Clinical Trials |

| SCI | Sleep Condition Indicator |

| SCS | Self-Compassion Scale |

| SF12 | Short Form 12 |

| SFFOI | Self-Forgiveness and Forgiveness of Others Index |

| SSS | Symptom Severity Scale |

| TFS | Toussaint Forgiveness Scale |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| WPI | Widespread Pain Index |

References

- Ablin, J. N., Oren, A., Cohen, S., Aloush, V., Buskila, D., Elkayam, O., Wollman, Y., & Berman, M. (2012). Prevalence of fibromyalgia in the Israeli population: A population-based study to estimate the prevalence of fibromyalgia in the Israeli population using the London Fibromyalgia Epidemiology Study Screening Questionnaire (LFESSQ). Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 30(Suppl. S74), 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Amonoo, H. L., Daskalakis, E., Deary, E. C., Guo, M., Boardman, A. C., Keane, E. P., Lam, J. A., Newcomb, R. A., Gudenkauf, L. M., Brown, L. A., Onyeaka, H. K., Lee, S. J., Huffman, J. C., & El-Jawahri, A. (2024). Gratitude, optimism, and satisfaction with life and patient-reported outcomes in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychooncology, 33(2), e6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, L. M., Bennett, R. M., Crofford, L. J., Dean, L. E., Clauw, D. J., Goldenberg, D. L., Fitzcharles, M.-A., Paiva, E. S., Staud, R., Sarzi-Puttini, P., Buskila, D., & Macfarlane, G. J. (2019). AAPT Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. The Journal of Pain, 20(6), 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzeni, F., Talotta, R., Masala, I. F., Giacomelli, C., Conversano, C., Nucera, V., Lucchino, B., Iannuccelli, C., Di Franco, M., & Bazzichi, L. (2019). One year in review 2019: Fibromyalgia. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 37(Suppl. S116), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bandieri, E., Borelli, E., Bigi, S., Mucciarini, C., Gilioli, F., Ferrari, U., Eliardo, S., Luppi, M., & Potenza, L. (2024). Positive psychological well-being in early palliative care: A narrative review of the roles of hope, gratitude, and death acceptance. Current Oncology, 31(2), 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäckryd, E., Tanum, L., Lind, A. L., Larsson, A., & Gordh, T. (2017). Evidence of both systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation in fibromyalgia patients, as assessed by a multiplex protein panel applied to the cerebrospinal fluid and to plasma. Journal of Pain Research, 10, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. M., Friend, R., Jones, K. D., Ward, R., Han, B. K., & Ross, R. L. (2009). The Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR): Validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 11(4), R120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. M., Jones, J., Turk, D. C., Russell, I. J., & Matallana, L. (2007). An internet survey of 2596 people with fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A. L., Prince, A., & Edsall, P. (2000). Quality of life issues for fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Care & Research, 13(1), 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, M., Poncin, E., Bovet, E., Tamches, E., Cantin, B., Pralong, J., & Borasio, G. D. (2023). Giving and receiving thanks: A mixed methods pilot study of a gratitude intervention for palliative patients and their carers. BMC Palliative Care, 22(1), 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardy, K., Klose, P., Welsch, P., & Häuser, W. (2018). Efficacy, acceptability and safety of cognitive behavioural therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome—A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. European Journal of Pain, 22(2), 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossema, E. R., van Middendorp, H., Jacobs, J. W., Bijlsma, J. W., & Geenen, R. (2013). Influence of weather on daily symptoms of pain and fatigue in female patients with fibromyalgia: A multilevel regression analysis. Arthritis Care & Research, 65(7), 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branco, J. C., Bannwarth, B., Failde, I., Abello Carbonell, J., Blotman, F., Spaeth, M., Saraiva, F., Nacci, F., Thomas, E., Caubère, J. P., Le Lay, K., Taieb, C., & Matucci-Cerinic, M. (2010). Prevalence of fibromyalgia: A survey in five European countries. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 39(6), 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosschot, J. F. (2002). Cognitive-emotional sensitization and somatic health complaints. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 43(2), 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. (2007). Temporal course and structural relationships among dimensions of temperament and DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorder constructs. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(2), 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, C. S., Clark, S. R., & Bennett, R. M. (1991). The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire: Development and validation. The Journal of Rheumatology, 18(5), 728–733. [Google Scholar]

- Casale, R., Sarzi-Puttini, P., Botto, R., Alciati, A., Batticciotto, A., Marotto, D., & Torta, R. (2019). Fibromyalgia and the concept of resilience. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 37(Suppl. S116), 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ceko, M., Bushnell, M. C., Fitzcharles, M. A., & Schweinhardt, P. (2013). Fibromyalgia interacts with age to change the brain. NeuroImage: Clinical, 3, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaaya, M., Slim, Z. N., Habib, R. R., Arayssi, T., Dana, R., Hamdan, O., Assi, M., Issa, Z., & Uthman, I. (2012). High burden of rheumatic diseases in Lebanon: A COPCORD study. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, 15(2), 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charzyńska, E., Offenbächer, M., Halverson, K., Hirsch, J. K., Kohls, N., Hanshans, C., Sirois, F., & Toussaint, L. (2025). Profiles of well-being and their associations with self-forgiveness, forgiveness of others, and gratitude among patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. British Journal of Health Psychology, 30(1), e12749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauw, D. J. (2014). Fibromyalgia: A clinical review. JAMA, 311(15), 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, L. F., Pellanda, L. C., & Reppold, C. T. (2019). Positive psychology and gratitude interventions: A randomized clinical trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diniz, G., Korkes, L., Tristão, L. S., Pelegrini, R., Bellodi, P. L., & Bernardo, W. M. (2023). The effects of gratitude interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Einstein, 21, eRW0371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, R. J., Bradley, G., & Morrissey, S. (2014). Positive predispositions, quality of life and chronic illness. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 19(4), 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, G. R., Kaplan, J., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. (2015). Neural correlates of gratitude. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, L. V., Zautra, A., Puente, C. P., López-López, A., & Valero, P. B. (2010). Cognitive-affective assets and vulnerabilities: Two factors influencing adaptation to fibromyalgia. Psychology & Health, 25(2), 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez-Sánchez, C. M., Duschek, S., & Reyes Del Paso, G. A. (2019). Psychological impact of fibromyalgia: Current perspectives. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 12, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendreau, R. M., McCracken, L. M., Williams, D. A., Luciano, J. V., Dai, Y., Vega, N., Ghalib, Z., Guthrie, K., Kraus, A. C., Rosenbluth, M. J., Vaughn, B., Zomnir, J. M., Reddy, D., Chadwick, A. L., Clauw, D. J., & Arnold, L. M. (2024). Self-guided digital behavioural therapy versus active control for fibromyalgia (PROSPER-FM): A phase 3, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 404(10450), 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, D. L. B., Arnold, L. M., Glass, J. M., & Clauw, D. J. (2008). Understanding fibromyalgia and its related disorders. The Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 10(2), 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, E., Elorza, J., & Failde, I. (2010). Fibromyalgia and psychiatric comorbidity: Their effect on the quality of life patients. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría, 38(5), 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Guermazi, M., Ghroubi, S., Sellami, M., Elleuch, M., Feki, H., André, E., Schmitt, C., Taieb, C., Damak, J., Baklouti, S., & Elleuch, M. H. (2008). Fibromyalgia prevalence in Tunisia [Prévalence de la fibromyalgie en Tunisie]. La Tunisie Médicale, 86(9), 806–811. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Alcedo, J., Toledo-Cárdenas, M., Curi Alcántara, E., & Diaz Medina, E. V. (2024). Gratitud y cáncer: Un análisis bibliométrico de la producción científica en Scopus (1991–2024). Psicooncología, 21(2), 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häuser, W., Brähler, E., Wolfe, F., & Henningsen, P. (2014). Patient Health Questionnaire 15 as a generic measure of severity in fibromyalgia syndrome: Surveys with patients of three different settings. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 76(4), 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häuser, W., Jung, E., Erbslöh-Möller, B., Gesmann, M., Kühn-Becker, H., Petermann, F., Langhorst, J., Weiss, T., Winkelmann, A., & Wolfe, F. (2012). Validation of the Fibromyalgia Survey Questionnaire within a cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE, 7(5), e37504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häuser, W., Sarzi-Puttini, P., & Fitzcharles, M. A. (2019). Fibromyalgia syndrome: Under-, over- and misdiagnosis. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 37(Suppl. S116), 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P. T., Morgan, R. L., Rooney, A. A., Taylor, K. W., Thayer, K. A., Silva, R. A., Lemeris, C., Akl, E. A., Bateson, T. F., Berkman, N. D., Glenn, B. S., Hróbjartsson, A., LaKind, J. S., McAleenan, A., Meerpohl, J. J., Nachman, R. M., Obbagy, J. E., O’Connor, A., Radke, E. G., … Sterne, J. A. C. (2024). A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E). Environment International, 186, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J. K., Altier, H. R., Offenbächer, M., Toussaint, L., Kohls, N., & Sirois, F. M. (2021). Positive psychological factors and impairment in rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease: Do psychopathology and sleep quality explain the linkage? Arthritis Care & Research, 73(1), 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J. K., & Sirois, F. M. (2016). Hope and fatigue in chronic illness: The role of perceived stress. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(4), 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, C. S., Lazaridou, A., Cahalan, C. M., Kim, J., Edwards, R. R., Napadow, V., & Loggia, M. L. (2020). Aberrant salience? Brain hyperactivation in response to pain onset and offset in fibromyalgia. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 72(7), 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannuccelli, C., Sarzi-Puttini, P., Atzeni, F., Cazzola, M., di Franco, M., Guzzo, M. P., Bazzichi, L., Cassisi, G. A., Marsico, A., Stisi, S., & Salaffi, F. (2011). Psychometric properties of the Fibromyalgia Assessment Status (FAS) index: A national web-based study of fibromyalgia. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 29(Suppl. S69), S49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Inanici, F., & Yunus, M. B. (2004). History of fibromyalgia: Past to present. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 8(5), 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. T., Atzeni, F., Beasley, M., Flüß, E., Sarzi-Puttini, P., & Macfarlane, G. J. (2015). The prevalence of fibromyalgia in the general population: A comparison of the American College of Rheumatology 1990, 2010, and modified 2010 classification criteria. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 67(2), 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J., Rutledge, D. N., Jones, K. D., Matallana, L., & Rooks, D. S. (2008). Self-assessed physical function levels of women with fibromyalgia: A national survey. Women’s Health Issues, 18(5), 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kini, P., Wong, J., McInnis, S., Gabana, N., & Brown, J. W. (2016). The effects of gratitude expression on neural activity. Neuroimage, 128, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinman, L., Mannix, S., Arnold, L. M., Burbridge, C., Howard, K., McQuarrie, K., Pitman, V., Resnick, M., Roth, T., & Symonds, T. (2014). Assessment of sleep in patients with fibromyalgia: Qualitative development of the fibromyalgia sleep diary. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacasse, A., Bourgault, P., & Choinière, M. (2016). Fibromyalgia-related costs and loss of productivity: A substantial societal burden. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 17, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhorst, J., Klose, P., Dobos, G. J., Bernardy, K., & Häuser, W. (2013). Efficacy and safety of meditative movement therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatology International, 33(1), 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layous, K., Kumar, S. A., Arendtson, M., & Najera, A. (2023). The effects of rumination, distraction, and gratitude on positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(5), 1053–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leça, S., & Tavares, I. (2022). Research in mindfulness interventions for patients with fibromyalgia: A critical review. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 16, 920271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlejohn, G. (2015). Neurogenic neuroinflammation in fibromyalgia and complex regional pain syndrome. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 11(11), 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, G. J., Kronisch, C., Atzeni, F., Häuser, W., Choy, E. H., Amris, K., Branco, J., Dincer, F., Leino-Arjas, P., Longley, K., McCarthy, G., Makri, S., Perrot, S., Sarzi Puttini, P., Taylor, A., & Jones, G. T. (2017). EULAR recommendations for management of fibromyalgia. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 76(12), e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhoul, M., & Bartley, E. J. (2023). Exploring the relationship between gratitude and depression among older adults with chronic low back pain: A sequential mediation analysis. Frontiers in Pain Research, 4, 1140778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, L. A., & Higgins, J. P. T. (2021). Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Research Synthesis Methods, 12(1), 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, P. J., Redwine, L., Wilson, K., Pung, M. A., Chinh, K., Greenberg, B. H., Lunde, O., Maisel, A., Raisinghani, A., Wood, A., & Chopra, D. (2015). The role of gratitude in spiritual well-being in asymptomatic heart failure patients. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 2(1), 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miró, E., Martínez, M. P., Sánchez, A. I., Prados, G., & Medina, A. (2011). When is pain related to emotional distress and daily functioning in fibromyalgia syndrome? The mediating roles of self-efficacy and sleep quality. British Journal of Health Psychology, 16(4), 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, I., Nishioka, K., Usui, C., Osada, K., Ichibayashi, H., Ishida, M., Turk, D. C., Matsumoto, Y., & Nishioka, K. (2014). An epidemiologic internet survey of fibromyalgia and chronic pain in Japan. Arthritis Care & Research, 66(7), 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M. Y., & Wong, W. S. (2013). The differential effects of gratitude and sleep on psychological distress in patients with chronic pain. Journal of Health Psychology, 18(2), 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A. D., Wilcox, K. T., Moskowitz, J. T., Wethington, E., Addington, E. L., Sanni, M. O., Kim, P., & Reid, M. C. (2023). Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a positive affect skills intervention for adults with fibromyalgia. Innovation in Aging, 7(10), igad070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, S., & Russell, I. J. (2014). More ubiquitous effects from non-pharmacologic than from pharmacologic treatments for fibromyalgia syndrome: A meta-analysis examining six core symptoms. European Journal of Pain, 18(8), 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, E., Kjøller, M., Jacobsen, S., Bülow, P. M., Danneskiold-Samsøe, B., & Kamper-Jørgensen, F. (1993). Fibromyalgia in the adult Danish population: I. A prevalence study. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology, 22(5), 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, L. P. (2013). Worldwide epidemiology of fibromyalgia. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 17(8), 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehm, S. E., Koroschetz, J., Gockel, U., Brosz, M., Freynhagen, R., Tölle, T. R., & Baron, R. (2010). A cross-sectional survey of 3035 patients with fibromyalgia: Subgroups of patients with typical comorbidities and sensory symptom profiles. Rheumatology, 49(6), 1146–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, R., Mork, P. J., Westgaard, R. H., Rø, M., & Lundberg, U. (2010). Fibromyalgia syndrome is associated with hypocortisolism. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 17(3), 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Pintó, I., Agmon-Levin, N., Howard, A., & Shoenfeld, Y. (2014). Fibromyalgia and cytokines. Immunology Letters, 161(2), 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A., Di Lollo, A. C., Guzzo, M. P., Giacomelli, C., Atzeni, F., Bazzichi, L., & Di Franco, M. (2015). Fibromyalgia and nutrition: What news? Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 33(Suppl. S88), S117–S125. [Google Scholar]

- Ruini, C., & Vescovelli, F. (2013). The role of gratitude in breast cancer: Its relationships with post-traumatic growth, psychological well-being and distress. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(1), 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaffi, F., De Angelis, R., & Grassi, W. (2005). Prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions in an Italian population sample: Results of a regional community-based study. I. The MAPPING study. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 23(6), 819–828. [Google Scholar]

- Salaffi, F., Franchignoni, F., Giordano, A., Ciapetti, A., Sarzi-Puttini, P., & Ottonello, M. (2013). Psychometric characteristics of the Italian version of the revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire using classical test theory and Rasch analysis. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 31(Suppl. S79), S41–S49. [Google Scholar]

- Salaffi, F., Sarzi-Puttini, P., Girolimetti, R., Gasparini, S., Atzeni, F., & Grassi, W. (2009). Development and validation of the self-administered Fibromyalgia Assessment Status: A disease-specific composite measure for evaluating treatment effect. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 11(4), R125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandıkçı, S. C., & Özbalkan, Z. (2015). Fatigue in rheumatic diseases. European Journal of Rheumatology, 2(3), 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, R. A., & Sansone, L. A. (2010). Gratitude and well being: The benefits of appreciation. Psychiatry, 7(11), 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sarzi-Puttini, P., Giorgi, V., Marotto, D., & Atzeni, F. (2020). Fibromyalgia: An update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 16(11), 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scammell, S. H. (2001). Illness as transformative gift in people with fibromyalgia. California Institute of Integral Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Scudds, R. A., Li, E. K. M., & Scudds, R. J. (2006). The prevalence of fibromyalgia syndrome in chinese people in Hong Kong. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain, 14(2), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology. An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senna, E. R., De Barros, A. L., Silva, E. O., Costa, I. F., Pereira, L. V., Ciconelli, R. M., & Ferraz, M. B. (2004). Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in Brazil: A study using the COPCORD approach. The Journal of Rheumatology, 31(3), 594–597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spaeth, M. (2009). Epidemiology, costs, and the economic burden of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 11(3), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staud, R., Robinson, M. E., Weyl, E. E., & Price, D. D. (2010). Pain variability in fibromyalgia is related to activity and rest: Role of peripheral tissue impulse input. The Journal of Pain, 11(12), 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J. A. C., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., Cates, C. J., Cheng, H. Y., Corbett, M. S., Eldridge, S. M., Emberson, J. R., Hernán, M. A., Hopewell, S., Hróbjartsson, A., Junqueira, D. R., Jüni, P., Kirkham, J. J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., … Higgins, J. P. T. (2019). RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T. T., Tan, M. P., Lam, C. L., Loh, E. C., Capelle, D. P., Zainuddin, S. I., Ang, B. T., Lim, M. A., Lai, N. Z., Tung, Y. Z., Yee, H. A., Ng, C. G., Ho, G. F., See, M. H., Teh, M. S., Lai, L. L., Pritam Singh, R. K., Chai, C. S., Ng, D. L. C., & Tan, S. B. (2023). Mindful gratitude journaling: Psychological distress, quality of life and suffering in advanced cancer: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 13(e2), e389–e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszek, K. (2023). Do positive emotions prompt people to be more authentic? The mediation effect of gratitude and empathy dimensions on the relationship between humility state and perceived false self. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 11(4), 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, L., Sirois, F., Hirsch, J., Weber, A., Vajda, C., Schelling, J., Kohls, N., & Offenbacher, M. (2017). Gratitude mediates quality of life differences between fibromyalgia patients and healthy controls. Quality of Life Research, 26(9), 2449–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhanoğlu, A. D., Yilmaz, Ş., Kaya, S., Dursun, M., Kararmaz, A., & Saka, G. (2008). The epidemiological aspects of fibromyalgia syndrome in adults living in turkey: A population based Study. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain, 16(3), 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçeyler, N., Häuser, W., & Sommer, C. (2011). Systematic review with meta-analysis: Cytokines in fibromyalgia syndrome. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierck, C. J., Jr. (2006). Mechanisms underlying development of spatially distributed chronic pain (fibromyalgia). PAIN, 124(3), 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, A., Lahr, B. D., Wolfe, F., Clauw, D. J., Whipple, M. O., Oh, T. H., Barton, D. L., & St Sauver, J. (2013). Prevalence of fibromyalgia: A population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, utilizing the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Arthritis Care & Research, 65(5), 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K. P., Speechley, M., Harth, M., & Ostbye, T. (1999). The London fibromyalgia epidemiology study: The prevalence of fibromyalgia syndrome in London, Ontario. The Journal of Rheumatology, 26(7), 1570–1576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, F., Clauw, D. J., Fitzcharles, M. A., Goldenberg, D. L., Häuser, W., Katz, R. L., Mease, P. J., Russell, A. S., Russell, I. J., & Walitt, B. (2016). 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 46(3), 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (2007). Coping style as a psychological resource of grateful people. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(9), 1076–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., Lloyd, J., & Atkins, S. (2009a). Gratitude influences sleep through the mechanism of pre-sleep cognitions. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 66(1), 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., & Maltby, J. (2009b). Gratitude predicts psychological well-being above the Big Five facets. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(4), 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Gillett, R., Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2008). The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(4), 854–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., & Tarrier, N. (2010). Positive clinical psychology: A new vision and strategy for integrated research and practice. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J. (2020). Gratitude and subjective well-being among Koreans. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S. L. K., Couto, L. A., & Marques, A. P. (2021). Effects of a six-week mobile app versus paper book intervention on quality of life, symptoms, and self-care in patients with fibromyalgia: A randomized parallel trial. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy, 25(4), 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. Y., Plamondon, A., Goldstein, A. L., Snorrason, I., Katz, J., & Björgvinsson, T. (2022). Dynamics of daily positive and negative affect and relations to anxiety and depression symptoms in a transdiagnostic clinical sample. Depression and Anxiety, 39(12), 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference Study Type Country(ies) * | Participant Characteristics | Intervention | Control | Measures of Effect | Main Results and Implications for Future Research | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scammell (2001) Qualitative study USA |

| Observational | Observational |

|

|

|

| Toussaint et al. (2017) Cross-sectional study Austria Germany UK USA |

| Observational | Observational |

|

|

|

| Hirsch et al. (2021) Cross-sectional study Austria Germany UK USA |

| Observational | Observational |

|

|

|

| Yuan et al. (2021) Randomized clinical trial Brazil |

| Mobile app ProFibro for 6 weeks (this app promotes the practice of gratitude and provides educational measures regarding FM) | Paper booklet of similar content to the content of the ProFibro app for 6 weeks |

|

|

|

| Ong et al. (2023) Randomized clinical trial USA |

| LARKSPUR group (49 subjects) for 5 weeks (this program included skill training that targeted 8 skills to help foster positive affect; one of them was gratitude) | Emotion reporting group (46 subjects) |

|

|

|

| Charzyńska et al. (2025) Cross-sectional study Austria Germany Poland UK USA |

| Observational | Observational |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carneiro, B.D.; Pozza, D.H.; Tavares, I. Can Gratitude Ease the Burden of Fibromyalgia? A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081079

Carneiro BD, Pozza DH, Tavares I. Can Gratitude Ease the Burden of Fibromyalgia? A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081079

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarneiro, Bruno Daniel, Daniel Humberto Pozza, and Isaura Tavares. 2025. "Can Gratitude Ease the Burden of Fibromyalgia? A Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081079

APA StyleCarneiro, B. D., Pozza, D. H., & Tavares, I. (2025). Can Gratitude Ease the Burden of Fibromyalgia? A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1079. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081079