Social Challenges on University Campuses: How Does Physical Activity Affect Social Anxiety? The Dual Roles of Loneliness and Gender

Abstract

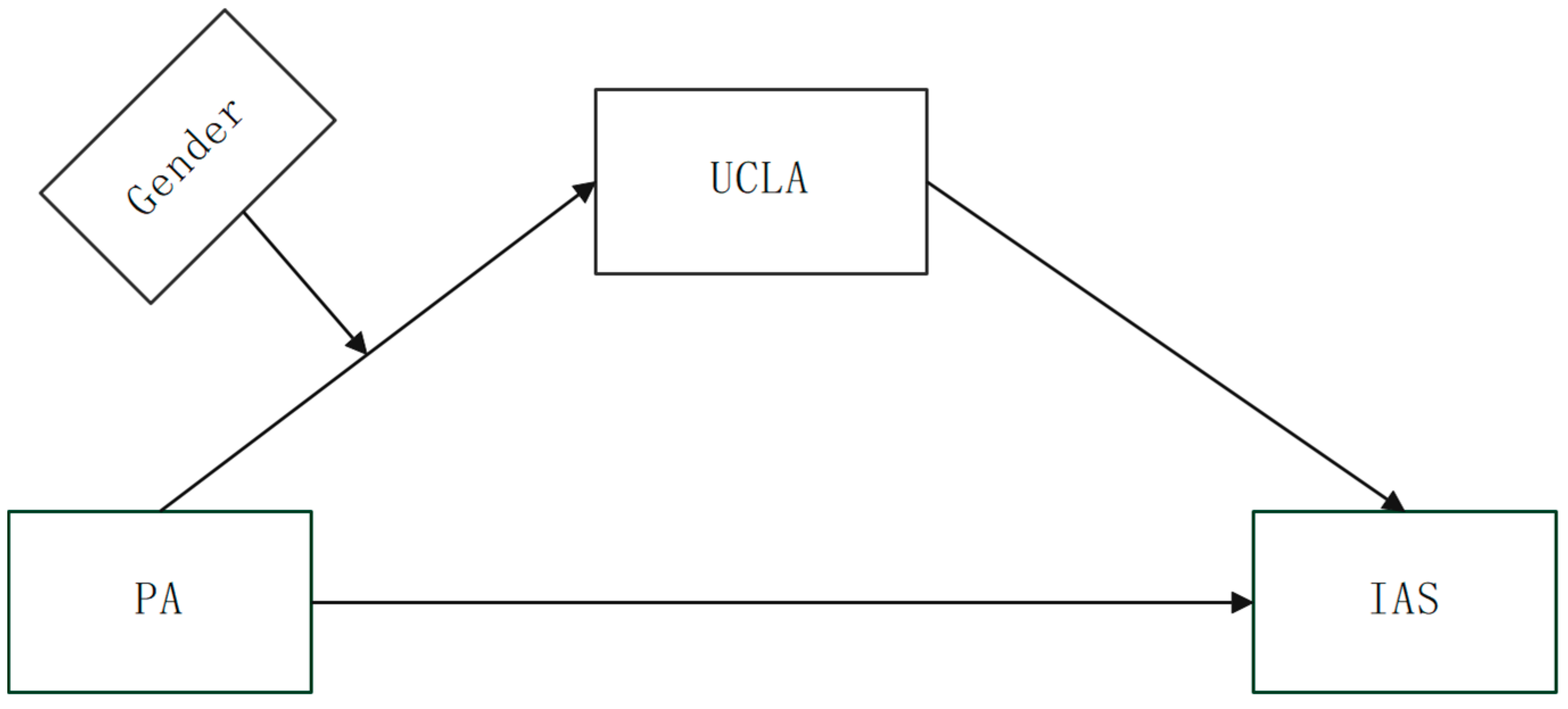

1. Introduction

1.1. Relationship Between Physical Activity and Social Anxiety

1.2. The Mediating Role of Loneliness

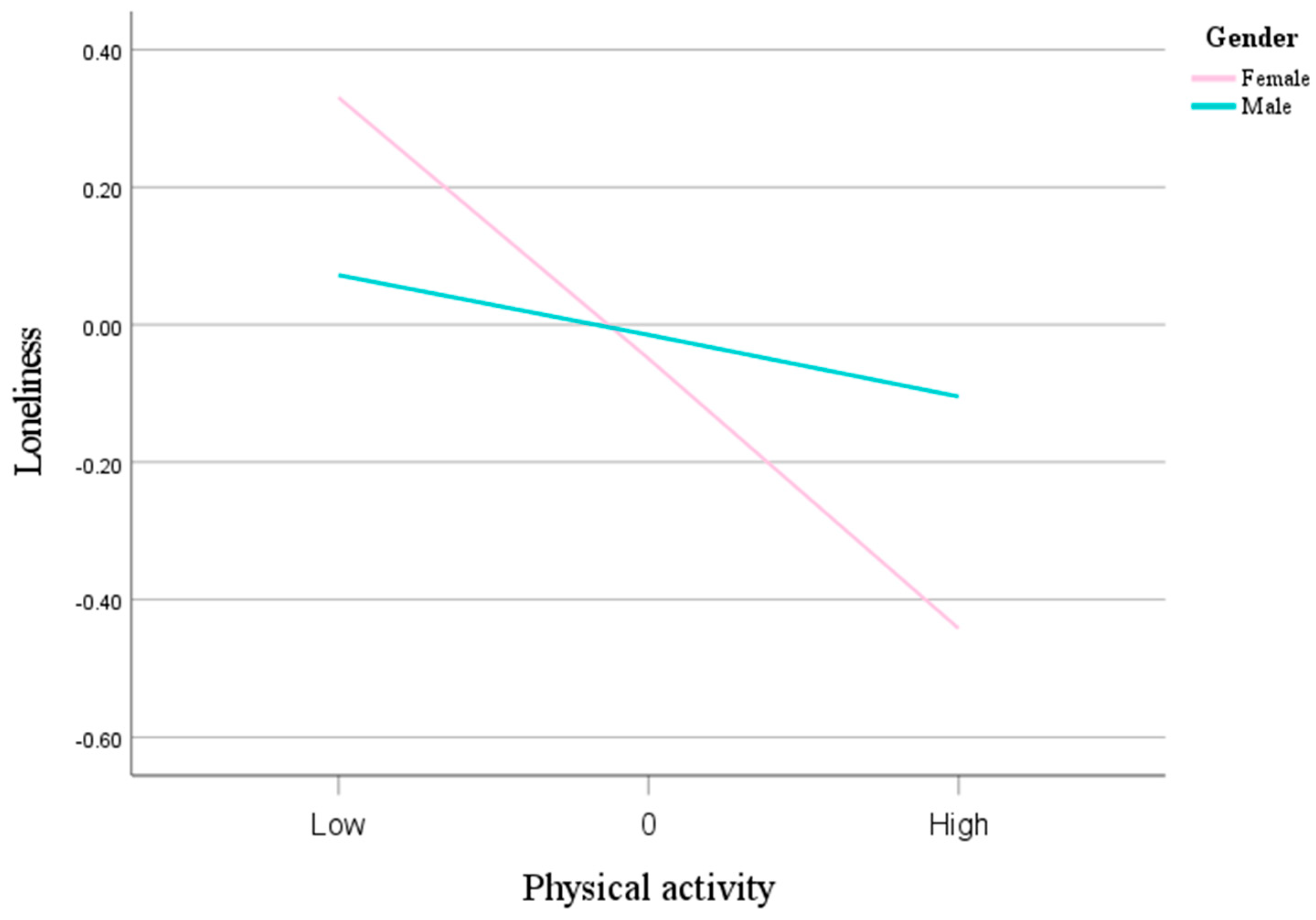

1.3. Gender Moderation Effect

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Process

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Physical Activity

2.2.2. Loneliness

2.2.3. Social Anxiety

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.3. Moderated Mediation Model Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Associations of Physical Activity with Loneliness and Social Anxiety

4.2. Loneliness as a Key Mechanism

4.3. The Moderating Role of Gender

4.4. Research Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahn, J., Falk, E. B., & Kang, Y. (2024). Relationships between physical activity and loneliness: A systematic review of intervention studies. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 6, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, G., & Carlbring, P. (2010). Social phobia (social anxiety disorder). In Stepped care and e-health (pp. 99–113). Springer New York. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, M., Asnaani, A., & Aderka, I. M. (2017). Gender differences in social anxiety disorder: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 56(56), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubert, S., Brazo-Sayavera, J., González, S. A., Janssen, I., Manyanga, T., Oyeyemi, A. L., Picard, P., Sherar, L. B., Turner, E., & Tremblay, M. S. (2021). Global prevalence of physical activity for children and adolescents; inconsistencies, research gaps, and recommendations: A narrative review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 18(1), 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, M. R., Araújo, C. L. P., Reichert, F. F., Siqueira, F. V., da Silva, M. C., & Hallal, P. C. (2007). Gender differences in leisure-time physical activity. International Journal of Public Health, 52(1), 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badcock, J. C., Shah, S., Mackinnon, A., Stain, H. J., Galletly, C., Jablensky, A., & Morgan, V. A. (2015). Loneliness in psychotic disorders and its association with cognitive function and symptom profile. Schizophrenia Research, 169(1), 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, M., Victor, C., Hammond, C., Eccles, A., Richins, M. T., & Qualter, P. (2021). Loneliness around the world: Age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 169(169), 110066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, E. E., & McNally, R. J. (2018). Exercise as a buffer against difficulties with emotion regulation: A pathway to emotional well-being. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 109(109), 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, M. E., Klein, E. M., Brähler, E., Reiner, I., Jünger, C., Michal, M., Wiltink, J., Wild, P. S., Münzel, T., Lackner, K. J., & Tibubos, A. N. (2017). Loneliness in the general population: Prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, J., & Sabiston, C. M. (2009). Social physique anxiety and physical activity: A self-determination theory perspective. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(3), 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., & Nakagawa, S. (2023). Recent advances in the study of the neurobiological mechanisms behind the effects of physical activity on mood, resilience and emotional disorders. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 32(9), 937–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryman, M. T., & Heimberg, R. G. (2018). Emotion regulation in social anxiety and depression: A systematic review of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Clinical Psychology Review, 65(1), 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (2012). Social role theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 458–476). Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eres, R., Lim, M. H., & Bates, G. (2023). Loneliness and social anxiety in young adults: The moderating and mediating roles of emotion dysregulation, depression and social isolation risk. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 96(3), 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijón Puerta, J., Galván Malagón, M. C., Khaled Gijón, M., & Lizarte Simón, E. J. (2022). Levels of stress, anxiety, and depression in university students from Spain and Costa Rica during periods of confinement and virtual learning. Education Sciences, 12(10), 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Baya, D., Mendoza, R., de Matos, M. G., & Tomico, A. (2017). Sport participation, body satisfaction and depressive symptoms in adolescence: A moderated-mediation analysis of gender differences. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 16(2), 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y. (2024). Social anxiety disorder: A general overview. SHS Web of Conferences, 193, 03013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S. N., Chishti, R., & Bano, M. (2018). Gender differences in social support, loneliness, and isolation among old age citizens. Peshawar Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences (PJPBS), 4(1), 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K. (2005). The relationship between exercise and mental health: A life stage perspective. Journal of Health Sciences, 27, 27–32. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behavior Research and Therapy, 98, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F., Zhou, Q., Li, J., Cao, R., & Guan, H. (2014). Effect of social support on depression of internet addicts and the mediating role of loneliness. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, I., Bolliger, C., Holmer, P., Dimech, A. S., Raguindin, P. F., & Michel, G. (2025). Social anxiety among young adults in Switzerland: A cross-sectional study on associations with sports and social support. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazaieri, H., Morrison, A. S., Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. J. (2014). The Role of Emotion and Emotion Regulation in Social Anxiety Disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(1), 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesús, E., & Puerta, J. G. (2022). Prediction of early dropout in higher education using the SCPQ. Cogent Psychology, 9(1), 2123588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesús, E., Puerta, J. G., Galván, C., & Gijón, M. K. (2024). Influence of self-efficacy, anxiety and psychological well-being on academic engagement during university education. Education Sciences, 14(12), 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, J., Kotarska, K., & Aboul-Enein, B. H. (2020). Physical exercise and catecholamines response: Benefits and health risk: Possible mechanisms. Free Radical Research, 54(2–3), 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M. R. (1983). A brief version of the fear of negative evaluation scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9(3), 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Chen, X., Zhu, Y., & Shi, X. (2024). Longitudinal associations of social anxiety trajectories with internet-related addictive behaviors among college students: A five-wave survey study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D. Q. (1994). Stress level of college students and its relationship with physical exercise. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 8(2). [Google Scholar]

- Lim, M. H., Rodebaugh, T. L., Zyphur, M. J., & Gleeson, J. F. M. (2016). Loneliness over time: The crucial role of social anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(5), 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y., & Fan, Z. (2022). The relationship between rejection sensitivity and social anxiety among Chinese college students: The mediating roles of loneliness and self-esteem. Current Psychology, 42(15), 12439–12448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftei, A., & Măirean, C. (2023). Put your phone down! Perceived phubbing, life satisfaction, and psychological distress: The mediating role of loneliness. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mennin, D. S., McLaughlin, K. A., & Flanagan, T. J. (2009). Emotion regulation deficits in generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and their co-occurrence. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(7), 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Day, E. B., Butler, R. M., Morrison, A. S., Goldin, P. R., Gross, J. J., & Heimberg, R. G. (2021). Reductions in social anxiety during treatment predict lower levels of loneliness during follow-up among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 78, 102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Day, E. B., Morrison, A. S., Goldin, P. R., Gross, J. J., & Heimberg, R. G. (2019). Social anxiety, loneliness, and the moderating role of emotion regulation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 38(9), 751–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peerenboom, L., Collard, R. M., Naarding, P., & Comijs, H. C. (2015). The association between depression and emotional and social loneliness in older persons and the influence of social support, cognitive functioning and personality: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 182, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pels, F., & Kleinert, J. (2016). Loneliness and physical activity: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 9(1), 231–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, M. A. M., & de Andrade, L. H. S. G. (2005). Physical activity and mental health: The association between exercise and mood. Clinics, 60(1), 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. E., & LoBue, C. (2024). The many facets of physical activity, sports, and mental health. International Review of Psychiatry, 36(3), 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, D. A., Goldenberg, A., Becerra, R., Boyes, M., Hasking, P., & Gross, J. J. (2021). Loneliness and emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 180, 110974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddervold, S., Haug, E., & Kristensen, S. M. (2024). Sports participation, body appreciation and life satisfaction in norwegian adolescents: A moderated mediation analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 52(6), 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodeiro, J., Olaya, B., Haro, J. M., Gabarrell-Pascuet, A., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Francia, L., Rodríguez-Prada, C., Dolz-del-Castellar, B., & Domènech-Abella, J. (2025). The longitudinal relationship among physical activity, loneliness, and mental health in middle-aged and older adults: Results from the Edad con Salud cohort. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 28, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness scale (version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y., Chen, S.-P., & Liu, L. (2023). The role of peer relationships and flow experience in the relationship between physical exercise and social anxiety in middle school students. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, M., Brundin, L., Erhardt, S., Hållmarker, U., James, S., & Deierborg, T. (2021). Physical activity is associated with lower long-term incidence of anxiety in a population-based, large-scale study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 714014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2(2), 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, R. P., Berrigan, D., Dodd, K. W., Masse, L. C., Tilert, T., & McDowell, M. (2008). Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 40(1), 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujimoto, M., Saito, T., Matsuzaki, Y., & Kawashima, R. (2024). Role of positive and negative emotion regulation in well-being and health: The interplay between positive and negative emotion regulation abilities is linked to mental and physical health. Journal of Happiness Studies, 25(1–2), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, D., & Karas Montez, J. (2010). Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(1), 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Liu, T., Jin, X., & Zhou, C. (2024). Aerobic exercise promotes emotion regulation: A narrative review. Experimental Brain Research, 242(4), 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J., Shao, Y., Hu, J., & Zhao, X. (2025a). The impact of physical exercise on adolescent social anxiety: The serial mediating effects of sports self-efficacy and expressive suppression. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 17(1), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J., Shao, Y., Zang, W., & Hu, J. (2025b). Is physical exercise associated with reduced adolescent social anxiety mediated by psychological resilience? Wave study in China. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 19(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G., Sun, K., Xue, Y., & Dong, D. (2024a). A chain-mediated model of the effect of physical exercise on loneliness. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 30798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G., Xiao, L.-R., Chen, Y.-H., Zhang, M., Peng, K.-W., & Wu, H.-M. (2024b). Association between physical activity and mental health problems among children and adolescents: A moderated mediation model of emotion regulation and gender. Journal of Affective Disorders, 369, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 372 | 58.3 |

| Female | 266 | 41.7 | |

| Grade | Freshman | 273 | 42.8 |

| Sophomore | 181 | 28.4 | |

| Junior | 123 | 19.3 | |

| Senior | 61 | 9.6 | |

| Age | M ± SD | 19.82 ± 1.39 | — |

| Variable M (SD) | Total | Male (N = 372) | Female (N = 266) | p-Value | Var | Skew | Kurt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19.81 (1.39) | ||||||

| PA | 20.17(20.84) | 23.60 (22.35) | 15.37 (17.45) | p < 0.01 | 434.25 | 1.494 | 1.811 |

| IAS | 49.42 (8.71) | 48.74 (9.05) | 50.37 (8.13) | p = 0.02 | 75.89 | −0.137 | 0.532 |

| UCLA | 45.39 (8.45) | 45.15 (8.64) | 45.73 (8.19) | p = 0.312 | 71.41 | −0.041 | 0.468 |

| Gender | PA | UCLA | IAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | |||

| PA | 0.195 ** | 1 | ||

| UCLA | −0.034 | −0.182 ** | 1 | |

| IAS | −0.092 * | −0.195 ** | 0.416 ** | 1 |

| Outcome Variable | Model 1UCLA | Model IAS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | p | β | SE | t | p | |

| Age | −0.0443 | 0.0566 | −0.7821 | 0.4344 | 0.0065 | 0.0523 | 0.1245 | 0.9009 |

| Grade | 0.0493 | 0.0567 | 0.8689 | 0.3852 | −0.0428 | 0.0523 | −0.8186 | 0.4133 |

| Gender | 0.0170 | 0.0403 | 0.4213 | 0.6737 | ||||

| PA | −0.2160 | 0.0407 | −5.3074 | <0.001 | −0.1217 | 0.0365 | −2.3377 | <0.001 |

| PA × Gender | 0.1494 | 0.0424 | 3.5209 | <0.001 | ||||

| UCLA | 0.3937 | 0.0364 | 10.8098 | <0.001 | ||||

| R2 | 0.0527 | 0.1890 | ||||||

| F | 7.0326 | 36.8679 | ||||||

| Type | Effect | SE | Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | −0.1545 | 0.0314 | −0.2240 | −0.0994 |

| Men | −0.0353 | 0.0208 | −0.0782 | −0.0039 |

| Moderated mediation index | 0.1192 | 0.0355 | 0.0557 | 0.1950 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nie, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, C.; Wang, T.; Zhou, F.; Gao, J. Social Challenges on University Campuses: How Does Physical Activity Affect Social Anxiety? The Dual Roles of Loneliness and Gender. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081063

Nie Y, Wang W, Liu C, Wang T, Zhou F, Gao J. Social Challenges on University Campuses: How Does Physical Activity Affect Social Anxiety? The Dual Roles of Loneliness and Gender. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081063

Chicago/Turabian StyleNie, Yuyang, Wenlei Wang, Cong Liu, Tianci Wang, Fangbing Zhou, and Jinchao Gao. 2025. "Social Challenges on University Campuses: How Does Physical Activity Affect Social Anxiety? The Dual Roles of Loneliness and Gender" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081063

APA StyleNie, Y., Wang, W., Liu, C., Wang, T., Zhou, F., & Gao, J. (2025). Social Challenges on University Campuses: How Does Physical Activity Affect Social Anxiety? The Dual Roles of Loneliness and Gender. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081063