Cognitive Distortions Associated with Loneliness: An Exploratory Study

Abstract

1. Cognitive Distortions Associated with Loneliness: An Exploratory Study

1.1. Loneliness

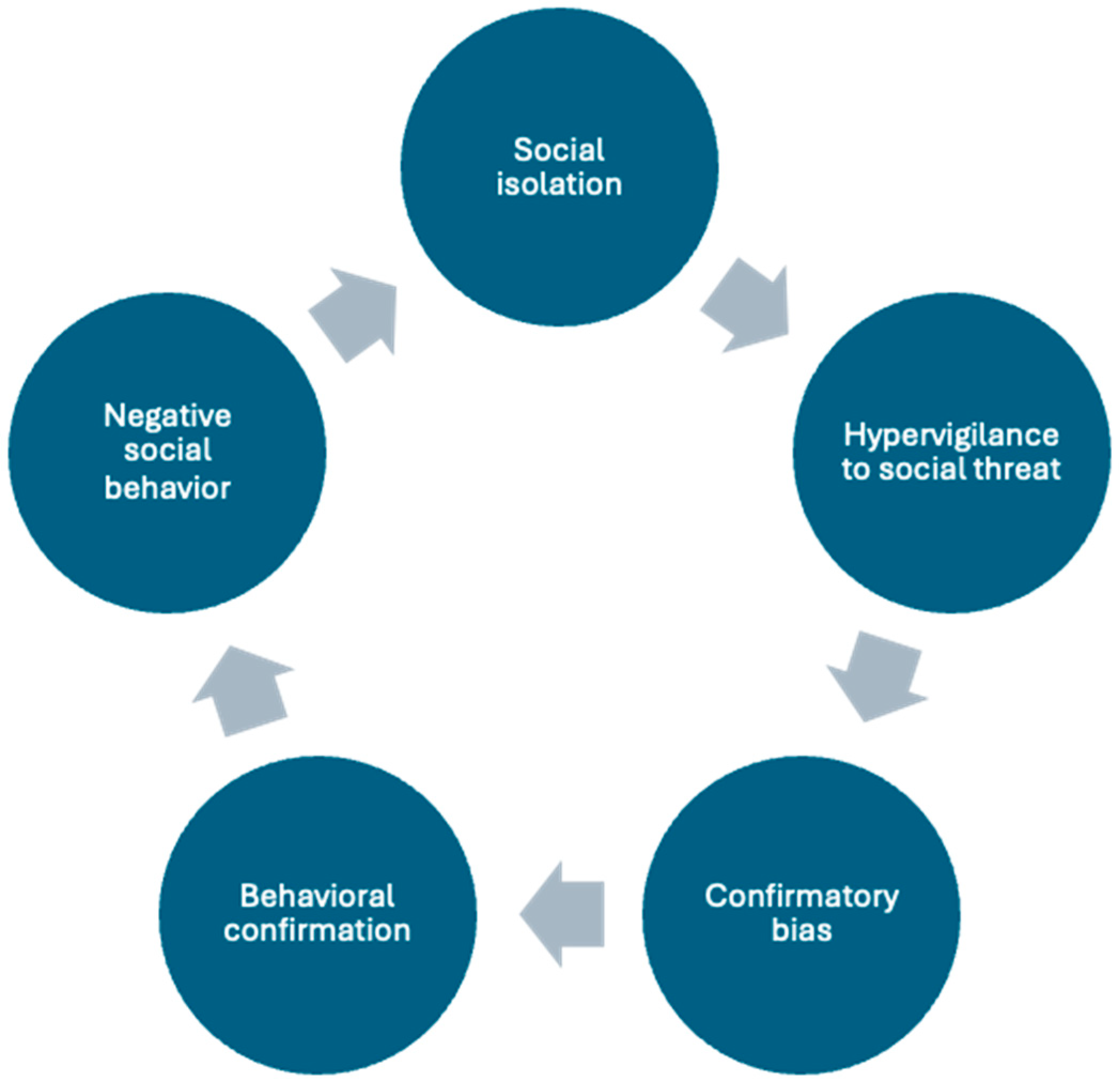

1.2. Cognitive Distortions in the Maintenance of Loneliness

1.3. Treatments Based on Challenging Cognitive Distortions

1.4. The Present Study

- RQ1.

- Among lonely individuals, which forms of cognitive distortion related to loneliness are most prevalent?

- RQ2.

- Among lonely individuals, which forms of cognitive distortion related to loneliness are most strongly correlated with the experience of loneliness?

- RQ3.

- Among lonely individuals, which forms of cognitive distortion related to loneliness mediate the association between loneliness and stress?

2. Method

2.1. Loneliness Pretest

2.2. Full Study

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Procedure

2.2.3. Measurement

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Dimension Reduction

3.3. Research Questions

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Liabilities and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This comparison temporarily suppressed the data of two participants whose reported gender was other than female or male due to the small cell size. |

| 2 | Racial comparisons were conducted separately because participants could select more than one racial identity. |

| 3 | Cell sizes for gender identity and racial identity sum to >237 because participants could select multiple categories. |

References

- Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression causes and treatment. University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, D. (1980). Feeling good. Morrow. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, D. (1989). The feeling good handbook. Morrow. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, D. (1999). The feeling good handbook (2nd ed.). HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J. T., Adler, A. B., Lester, P. B., McGurk, D., Thomas, J. L., Chen, H. Y., & Cacioppo, S. (2015). Building social resilience in soldiers: A double dissociative randomized controlled study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(1), 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging, 21(1), 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, S., Bangee, M., Balogh, S., Cardenas-Iniguez, C., Qualter, P., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2016). Loneliness and implicit attention to social threat: A high-performance electrical neuroimaging study. Cognitive Neuroscience, 7(1–4), 138–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, D. A. (2013). Cognitive restructuring. In S. G. Hofmann (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of cognitive behavioral therapy. Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J. D., Irwin, M. R., Burklund, L. J., Lieberman, M. D., Arevalo, J. M., Ma, J., Breen, E. C., & Cole, S. W. (2012). Mindfulness-based stress reduction training reduces loneliness and pro-inflammatory gene expression in older adults: A small randomized controlled trial. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 26(7), 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudjoe, T. K. M., Roth, D. L., Szanton, S. L., Wolff, J. L., Boyd, C. M., & Thorpe, R. J. (2020). The epidemiology of social isolation: National health and aging trends study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(1), 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, N. (2020). Governing through kodokushi. Japan’s lonely deaths and their impact on community self-government. Contemporary Japan, 32(1), 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBerard, M. S., & Kleinknecht, R. A. (1995). Loneliness, duration of loneliness, and reported stress symptomatology. Psychological Reports, 76(Suppl. S3), 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiJulio, B., Hamel, L., Muñana, C., & Brodie, M. (2018). Loneliness and social isolation in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan: An international survey. The Kaiser Family Foundation. Available online: https://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Loneliness-and-Social-Isolation-in-the-United-States-the-United-Kingdom-and-Japan-An-International-Survey (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Dobson, K. S., & Dozois, D. J. A. (2010). Historical and philosophical bases of the cognitive-behavioral therapies. In K. S. Dobson (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies (3rd ed., pp. 3–38). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, A. M., & Qualter, P. (2020). Alleviating loneliness in young people: A meta-analysis of interventions. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 26(1), 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A., & MacLaren, C. (2005). Rational emotive behavior therapy: A therapist’s guide (2nd ed.). Impact Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Erzen, E., & Çikrikci, Ö. (2018). The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 64(5), 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, K., Ray, C. D., James, R., & Anderson, A. J. (2023). Correlates of compassion for suffering social groups. Southern Communication Journal, 84(4), 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A., & DeWolf, R. (1992). The 10 dumbest mistakes smart people make and how to avoid them. HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, A., & Lurie, M. (1994). Depression: A cognitive therapy approach—A viewer’s manual. Newbridge Professional Programs. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, A., & Oster, C. (1999). Cognitive behavior therapy. In M. Hersen, & A. S. Bellack (Eds.), Handbook of comparative interventions for adult disorders (2nd ed., pp. 108–138). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Gerino, E., Rollè, L., Sechi, C., & Brustia, P. (2017). Loneliness, resilience, mental health, and quality of life in old age: A structural equation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerst-Emerson, K., & Jayawardhana, J. (2015). Loneliness as a public health issue: The impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. American Journal of Public Health, 105(5), 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilson, M., & Freeman, A. (1999). Overcoming depression: A cognitive therapy approach for taming the depression BEAST: Client workbook. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, R., Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., Speicher, C. E., & Holliday, J. E. (1985). Stress, loneliness, and changes in herpesvirus latency. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 8(3), 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, S. K., Pellmar, T. C., Kleinman, A. M., & Bunney, W. E. (Eds.). (2002). Reducing suicide: A national imperative. National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, R. A., Hudson, J. L., & Chilcot, J. (2020). Loneliness and type 2 diabetes incidence: Findings from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Diabetologia, 63, 2329–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickin, N., Käll, A., Shafran, R., Sutcliffe, S., Manzotti, G., & Langan, D. (2021). The effectiveness of psychological interventions for loneliness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 88, 102066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollon, D. S., & Dimidjian, S. (2009). Cognitive and behavioral treatments of depression. In I. H. Gotlib, & C. L. Hammen (Eds.), Handbook of depression (2nd ed., pp. 586–603). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, M. A., Chu, C., Rogers, M. L., & Joiner, T. E. (2020). A meta-analysis of the relationship between sleep problems and loneliness. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(5), 799–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P., McGinty, G., Karatzias, T., Murphy, J., Vallières, F., & McHugh Power, J. (2018). Can the REBT theory explain loneliness? Theoretical and clinical applications. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 48(1), 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, I., Kelly, P. J., Deane, F. P., Baker, A. L., Goh, M. C. W., Raftery, D. K., & Dingle, G. A. (2020). Loneliness among people with substance use problems: A narrative systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Review, 39(5), 447–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaremka, L. M., Fagundes, C. P., Glaser, R., Bennett, J. M., Malarkey, W. B., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2013). Loneliness predicts pain, depression, and fatigue: Understanding the role of immune dysregulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(8), 1310–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, M. A., Padmanabhanunni, A., & Chipps, J. (2019). An evaluation of a low-intensity cognitive behavioral therapy mHealth-supported intervention to reduce loneliness in older people. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L., Jin, Y., Zhang, X., Wang, F., Song, Y., & Xing, F. (2018). The effect of Baduanjin qigong combined with CBT on physical fitness and psychological health of elderly housebound. Medicine, 97(51), e13654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, J., Hanschmidt, F., & Kersting, A. (2021). The association between therapeutic alliance and outcome in internet-based psychological interventions: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 114, 106512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käll, A., Jägholm, S., Hesser, H., Andersson, F., Mathaldi, A., Norkvist, B. T., Shafran, R., & Andersson, G. (2020). Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for loneliness: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 51(1), 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremers, I. P., Steverink, N., Albersnagel, F. A., & Slaets, J. P. (2006). Improved self management ability and well-being in older women after a short group intervention. Aging and Mental Health, 10(5), 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liebke, L., Bungert, M., Thome, J., Hauschild, S., Gescher, D. M., Schmahl, C., Bohus, M., & Lis, S. (2016). Loneliness, social networks, and social functioning in borderline personality disorder. Personality Disorders, 8(4), 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Hawkley, L. C., Waite, L. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Social Science & Medicine, 74(6), 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, C. M., Chen, H. Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 219–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, H., Bebbington, P., Dennis, M. S., Jenkins, R., McManus, S., & Brugha, T. S. (2013). Feelings of loneliness among adults with mental disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(1), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren-Yagoda, R., Melamud-Ganani, I., & Aderka, I. M. (2022). All by myself: Loneliness in social anxiety disorder. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science, 131(1), 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, U., & Tuncay, T. (2008). Correlates of loneliness among university students. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C., Majeed, A., Gill, H., Tamura, J., Ho, R. C., Mansur, R. B., Nasri, F., Lee, Y., Rosenblat, J. D., Wong, E., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). The effect of loneliness on distinct health outcomes: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 294, 113514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, E., Bu, F., & Fancourt, D. (2021). Loneliness and risk for cardiovascular disease: Mechanisms and future directions. Current Cardiology Reports, 23(6), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perissinotto, C. M., Cenzer, I. S., & Covinsky, K. E. (2012). Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(14), 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R., Van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., Bangee, M., Maes, M., & Verhagen, M. (2015). Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, T., Elliott, P., & Roberts, R. (2017). Relationship between loneliness and mental health in students. Journal of Public Mental Health, 16(2), 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D. (1996). UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, L., & Fox, M. (2019). The comprehensive clinician’s guide to cognitive behavioral therapy. PSEI Publishing & Media. [Google Scholar]

- Stickley, A., & Koyanagi, A. (2016). Loneliness, common mental disorders and suicidal behavior: Findings from a general population survey. Journal of Affective Disorders, 197, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, A., Adolfsson, A. N., Nordin, M., & Adolfsson, R. (2020). Loneliness increases the risk of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(5), 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surkalim, D. L., Luo, M., Eres, R., Gebel, K., van Buskirk, J., Bauman, A., & Ding, D. (2022). The prevalence of loneliness across 113 countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 376, e067068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurston, R. C., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2009). Women, loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(8), 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). Nation: United States. U.S. Department of Commerce. Available online: https://data.census.gov/profile/United_States?g=010XX00US (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S., & Hanratty, B. (2016). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart, 102(3), 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, C. R., & Yang, K. (2012). The prevalence of loneliness among adults: A case study of the United Kingdom. The Journal of Psychology, 146(1–2), 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J. E. (1982). Loneliness, depression and cognitive therapy: Theory and application. In L. A. Peplau, & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 379–406). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N., Fan, F. M., Huang, S. Y., & Rodriguez, M. A. (2018). Mindfulness training for loneliness among Chinese college students: A pilot randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Psychology, 53(5), 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | M/SD | r with Loneliness |

|---|---|---|

| I feel that I am disconnected from others, and because I feel that way, it is therefore true. | 4.42/1.66 | 0.38 ** |

| I use my emotions to tell me what’s true about my relationships. | 4.18/1.46 | 0.07 |

| How do I know that others reject me? I know because I feel it. | 4.18/1.75 | 0.27 ** |

| Even when they don’t say so, I can tell other people don’t want to be emotionally connected to me. | 4.35/1.70 | 0.31 ** |

| I know other people think poorly of me, even when they don’t tell me that. | 4.17/1.73 | 0.28 ** |

| When I feel lonely, it is the worst thing in the world. | 3.42/1.83 | 0.22 ** |

| Feeling lonely is terrible and I cannot stand it. | 3.82/1.78 | 0.24 ** |

| Being lonely is the worst thing that could happen to me. | 2.75/1.76 | 0.21 ** |

| I cannot stand feeling lonely. | 3.70/1.82 | 0.23 ** |

| Other people need to change their behaviors so that I feel less lonely. | 2.52/1.49 | 0.07 |

| Other people should change how they interact with me so that I feel more connected. | 2.59/1/61 | 0.06 |

| Being lonely isn’t my fault; I am a victim of what happens around me. | 3.02/1.45 | 0.14 * |

| I am lonely because of my circumstances. | 5.00/1.71 | 0.24 ** |

| I have no control over how lonely I am. | 3.48/1.60 | 0.25 ** |

| Nobody wants to be emotionally connected to me, ever. | 3.36/1.80 | 0.46 ** |

| Everyone I want to feel emotionally connected to rejects me. | 3.34/1.72 | 0.34 ** |

| I always feel rejected by others. | 3.98/1.84 | 0.31 ** |

| I had a hard time connecting with someone once. I will feel lonely forever. | 2.93/1.72 | 0.23 ** |

| In the past, I have had difficulty forming positive emotional connections. I am destined to feel lonely for the rest of my life. | 3.78/1.88 | 0.32 ** |

| Even though I have had good relationships before, I am destined to be lonely. | 3.73/1.88 | 0.37 ** |

| I’ve had some emotional connections with people in the past, but those don’t count; I am likely to be lonely forever. | 3.12/1.74 | 0.31 ** |

| It isn’t fair that I am as lonely as I am. | 3.63/1.83 | 0.23 ** |

| If life were more fair, I wouldn’t be so lonely. | 3.65/1.86 | 0.26 ** |

| If I can just tolerate my loneliness now, I know I will be rewarded later. | 3.19/1.71 | −0.23 ** |

| If I bear my lonely feelings now, I’ll be rewarded in the future. | 3.03/1.60 | −0.23 ** |

| If I am lonely, that must mean I deserve to be lonely. | 3.07/1.84 | 0.27 ** |

| I wouldn’t be lonely if I didn’t deserve to be. | 3.00/1.77 | 0.21 ** |

| I am simply the kind of person who tends to be lonely. | 4.97/1.75 | 0.42 ** |

| I’m just the type of person who is usually lonely. | 4.71/1.81 | 0.40 ** |

| Other people are either with me or against me. | 3.39/1.81 | 0.19 ** |

| In relationships, I am either a success or I’m a total failure. | 3.80/1.72 | 0.09 |

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How do I know that others reject me? I know it because I feel it. | 0.77 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.07 |

| Even when they don’t say so, I can tell other people don’t want to be emotionally connected to me. | 0.72 | 0.12 | −0.05 | 0.11 | −0.15 | 0.14 |

| I use my emotions to tell me what’s true about my relationships. | 0.65 | −0.19 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.16 | −0.23 |

| I know other people think poorly of me, even when they don’t tell me that. | 0.64 | 0.15 | −0.02 | 0.13 | −0.25 | 0.22 |

| If I can just tolerate my loneliness now, I know I will be rewarded later. | −0.02 | 0.89 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.07 |

| If I bear my lonely feelings now, I’ll be rewarded in the future. | 0.06 | 0.89 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.11 | −0.10 |

| When I feel lonely, it is the worst feeling in the world. | 0.03 | −0.04 | −0.90 | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.03 |

| I cannot stand feeling lonely. | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.89 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Feeling lonely is terrible and I cannot stand it. | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.88 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Being lonely is the worst thing that could happen to me. | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.82 | −0.10 | −0.05 | −0.09 |

| I am simply the kind of person who tends to be lonely. | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| I’m just the type of person who is usually lonely. | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.88 | 0.01 | −0.03 |

| I am lonely because of my circumstances. | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.73 | −0.03 | −0.04 |

| I wouldn’t be lonely if I didn’t deserve to be. | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.92 | −0.02 |

| If I am lonely, that must mean I deserve to be lonely. | 0.06 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.08 | −0.83 | 0.01 |

| I’ve had some emotional connections with people in the past, but those don’t count; I am likely to be lonely forever. | 0.13 | −0.18 | 0.02 | 0.18 | −0.54 | −0.27 |

| Other people need to change their behaviors so that I feel less lonely. | −0.08 | 0.10 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.20 | −0.83 |

| Other people should change how they interact with me so that I feel more connected. | 0.14 | 0.16 | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.06 | −0.79 |

| Internal Reliability (Alpha) | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Mean | 4.22 | 3.11 | 3.42 | 4.76 | 3.06 | 2.42 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.27 | 1.53 | 1.57 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.42 |

| Dimension | Mean |

|---|---|

| Mindreading | 4.22 a |

| Future Reward | 3.11 b |

| Catastrophizing | 3.42 c |

| Essentializing | 4.76 d |

| Deservedness | 3.06 b |

| Externalizing | 2.42 e |

| Total Effect B (p) | Direct Effect B (p) | Relationship | Indirect Effect B [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress → Loneliness | Stress → Loneliness | Stress → Mindreading → Loneliness | 0.14 [0.05, 0.26] |

| 0.60 (<0.001) | 0.15 (0.20) | Stress → Future Reward → Loneliness | 0.05 [−0.01, 0.13] |

| Stress → Catastrophizing→ Loneliness | 0.07 [0.01, 0.15] | ||

| Stress → Essentializing→ Loneliness | 0.13 [0.02, 0.26] | ||

| Stress → Deservedness → Loneliness | 0.04 [−0.05, 0.15] | ||

| Stress → Externalizing → Loneliness | 0.002 [−0.03, 0.03] | ||

| Total Indirect Effect | 0.45 [0.29, 0.62] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Floyd, K.; Ray, C.D.; Boumis, J.K. Cognitive Distortions Associated with Loneliness: An Exploratory Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081061

Floyd K, Ray CD, Boumis JK. Cognitive Distortions Associated with Loneliness: An Exploratory Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081061

Chicago/Turabian StyleFloyd, Kory, Colter D. Ray, and Josephine K. Boumis. 2025. "Cognitive Distortions Associated with Loneliness: An Exploratory Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081061

APA StyleFloyd, K., Ray, C. D., & Boumis, J. K. (2025). Cognitive Distortions Associated with Loneliness: An Exploratory Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081061