Transforming Pedagogical Practices and Teacher Identity Through Multimodal (Inter)action Analysis: A Case Study of Novice EFL Teachers in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Teacher Identity and Pedagogical Practices: A Theoretical Overview

2.2. Multimodal Strategies as Sites of Identity Construction

2.3. Negotiation of Teacher Identities: Novice English Educators in Chinese Classrooms

2.4. Analytical Framework: Multimodal (Inter)action Analysis

3. Study Design

- −

- Pitch is a mode of auditory modulation. Pitch enhancement can facilitate adult vocabulary learning across different visual contexts (Filippi et al., 2014). By altering the pitch range, secondary school learners can be subtly guided without direct feedback (Sikveland et al., 2021). This study used Praat’s software (version 6.3.08) (Boersma & Weenink, 2023) to automatically generate pitch and intensity contours, enabling the precise analysis of acoustic properties such as pitch (frequency) and intensity (amplitude) over time (Boersma & Weenink, 2023).

- −

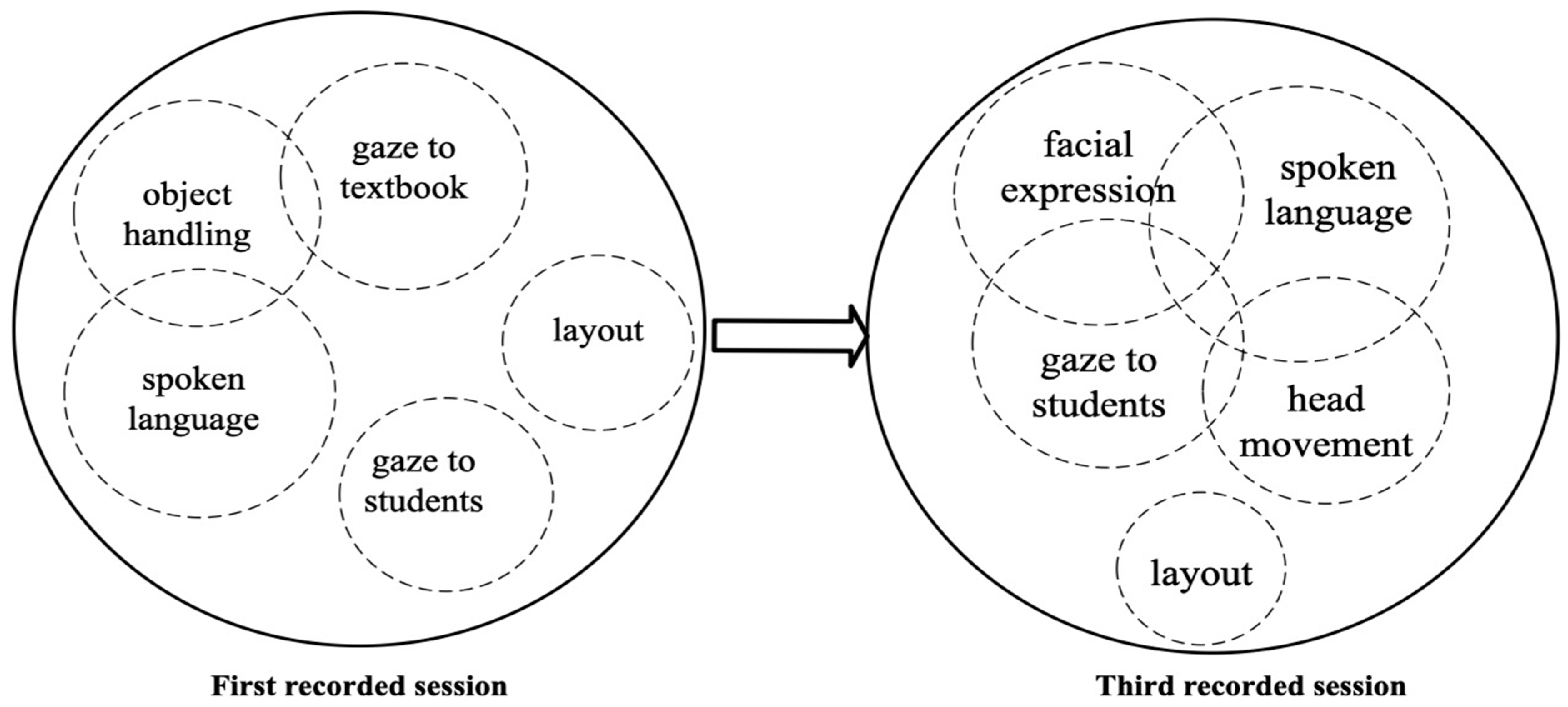

- Layout: “A mode that informs people about the distance between objects, the environment, and the people (inter)acting” (Norris, 2019). In a classroom, layout is reflected in how tables and chairs are arranged, along with elements like pictures, a blackboard, and a screen.

- −

- Gesture: “A mode that tells us how individuals hold and move their arms, hands, and fingers” (Norris, 2019). Teachers’ gestures in the classroom involve natural interactions with students or teaching tools, such as a blackboard, computer, or mouse (Q. Liu et al., 2022).

- −

- Gaze: “A mode that tells us how individuals look at something or someone” (Norris, 2019). For example, when a teacher notices a student playing with their phone in class, he will look at the student to inform him not to do so.

- −

- Head movement: “A mode that tells us how individuals hold and move their heads” (Norris, 2019). For example, if the teacher wishes to explain the knowledge points in a PowerPoint, then they move their head from the students to the screen.

- −

- Facial expression: “A mode that tells us how individuals maintain and change their expressions on the face” (Norris, 2019). For example, when the teacher asks students questions, they always wear a smile to foster a sense of closeness.

- −

4. Findings

4.1. Shared Beginnings: Teacher-Centered Practices and Passive Knowledge Transmitters

4.2. Teacher A’s Identity Trajectory: From Compliance to Dialogic Enactment

4.3. Shifts in Scales of Actions and Modal Configurations: A Comparative Analysis of Teacher A

4.4. Teacher B’s Identity Development: Navigating Experimentation to Enacted Dialogism

4.5. Shifts in Scales of Actions and Modal Configurations: A Comparative Analysis of Teacher B

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullah, H. M. F., Gaffar, A., & Arifin, S. (2023). Implementation of multiliteration pedagogy in education: A socio-cultural perspective. FIKROTUNA: Jurnal Pendidikan dan Manajemen Islam, 12(02), 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J. (2015). Analysing the construction of modal configurations with mediating digital texts in the classroom. Multimodal Communication, 4(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aini, R. N., Drajati, N. A., & Putra, K. A. (2024). Teacher-student interaction in EFL classrooms through creative problem-solving: An Application of the initiation-response-feedback model. Voices of English Language Education Society, 8(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinola, O. A. (2014). The use of non–verbal communication in the teaching of English language. Journal of Advances in Linguistics, 4(3), 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer-Kuhn, B., Lee, Y., Finnessey, S., & Liu, J. (2020). Inquiry-based learning as a facilitator to student engagement in undergraduate and graduate social work programs. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 8(1), 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldry, A. P., & Thibault, P. J. (2006). Multimodal transcription and text analysis: A multimedia toolkit and coursebook. Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, X. (2017). Application of multimodality to teaching reading. English Language and Literature Studies, 7(3), 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barany, L. K. (2016). Language awareness, intercultural awareness and communicative language teaching: Towards language education. International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies, 2(4), 158–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhuizen, G. (2016). Narrative approaches to exploring language, identity and power in language teacher education. RELC Journal, 47(1), 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J. M. (2015). The SAGE encyclopedia of intercultural competence. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernad-Mechó, E. (2023). Combining multimodal techniques to approach the study of academic lectures: A methodological reflection. In Multimodality studies in international contexts (pp. 92–110). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezemer, J., & Jewitt, C. (2018). Multimodality: A guide for linguists. Research Methods in Linguistics, 28, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. (1999). What the student does: Teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research & Development, 18(1), 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blommaert, J., & Huang, A. (2015). Historical bodies and historical space. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 6(3), 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2023). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer [Computer program], Version 6.3.08; Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Bourne, J., & Jewitt, C. (2003). Orchestrating debate: A multimodal analysis of classroom interaction. Reading, 37(2), 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, M. P., & Markarian, W. C. (2015). Dialogic teaching and dialogic stance: Moving beyond interactional form. Research in the Teaching of English, 49(3), 272–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G., & Yule, G. (1983). Discourse analysis. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brône, G., Oben, B., Jehoul, A., Vranjes, J., & Feyaerts, K. (2017). Eye gaze and viewpoint in multimodal interaction management. Cognitive Linguistics, 28(3), 449–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A. C., Godbole, N., & Marsh, E. J. (2013). Explanation feedback is better than correct answer feedback for promoting transfer of learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(2), 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, M. (2020). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence: Revisited. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Camicia, S. P., & Zhu, J. (2011). Citizenship education under discourses of nationalism, globalization, and cosmopolitanism: Illustrations from China and the United States. Frontiers of Education in China, 6(4), 602–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of commuicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, S. H., O’Connor, C., & Anderson, N. C. (2003). Classroom discussions using math talk in elementary classrooms (vol. 11). Math Solutions. [Google Scholar]

- Chee, Y. S., Mehrotra, S., & Ong, J. C. (2014). Facilitating dialog in the game-based learning classroom: Teacher challenges reconstructing professional identity. Digital Culture & Education. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M., Zhang, W., & Zheng, Q. (2023). Academic literacy development and professional identity construction in non-native English-speaking novice English language teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1190312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H. Y., & Ding, Q. (2021). Examining the behavioral features of Chinese teachers and students in the learner-centered instruction. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 36(1), 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilwant, K. (2012). Comparison of two teaching methods, structured interactive lectures and conventional lectures. Biomedical Research, 23(3), 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensson, J. (2021). Teacher identity as discourse: A case study of students in Swedish teacher education. Department of Swedish and Multilingualism, Stockholm University. [Google Scholar]

- Crozet, C. (2016). The intercultural foreign language teacher: Challenges and choices. In The critical turn in language and intercultural communication pedagogy (pp. 167–185). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C. (2011). Uncertain professional identities: Managing the emotional contexts of teaching. In New understandings of teacher’s work: Emotions and educational change (pp. 45–64). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10(3), 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M. M., & Barbosa, A. F. (2023). Multimodal positioning of (future) multilingual teachers of EFL. In Multimodal communication in intercultural interaction (pp. 141–168). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, P. A., & Uchida, Y. (1997). The negotiation of teachers’ sociocultural identities and practices in postsecondary EFL classrooms. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 451–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzedzickis, A., Kaklauskas, A., & Bucinskas, V. (2020). Human emotion recognition: Review of sensors and methods. Sensors, 20(3), 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, D., & Mercer, N. (1987). Common knowledge: The development of understanding in the classroom. Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., O’sullivan, M., Chan, A., Diacoyanni-Tarlatzis, I., Heider, K., Krause, R., LeCompte, W. A., Pitcairn, T., & Ricci-Bitti, P. E. (1987). Universals and cultural differences in the judgments of facial expressions of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(4), 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erfanian Mohammadi, J., Elahi Shirvan, M., & Akbari, O. (2019). Systemic functional multimodal discourse analysis of teaching students developing classroom materials. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(8), 964–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, P., Gingras, B., & Fitch, W. T. (2014). Pitch enhancement facilitates word learning across visual contexts. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, E. M. A., Reijs, R. P., Leenders, H. H. M., Jansen, M. W. J., & Hoebe, C. J. P. A. (2024). Co-creation and decision-making with students about teaching and learning: A systematic literature review. Journal of Educational Change, 25(1), 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafar, Z. N. (2023). The Teacher-centered and the student-centered: A comparison of two approaches. International Journal of Arts and Humanities, 1(1), 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (1983). The interaction order: American sociological association, 1982 presidential address. American Sociological Review, 48(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzar, J. (2020). Teacher identity formation through classroom practices in the post-method era: A systematic review. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1853304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J. (2022). College English education in China: From curriculum formulation to implementation reality. Saint Louis University. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, M., & Benson, P. (2015). The formation of English teacher identities: A cross-cultural investigation. Language Teaching Research, 19(2), 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G., & Zhu, M. (2019). Identity construction of Chinese business english teachers from the perspective of ESP theory. International Education Studies, 12(7), 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, M. M., Zaid, R., & Shah, S. A. (2023). Effects of teacher teaching approaches on students engagement and comprehension at university level. Journal of Social Sciences Review, 3(2), 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, R., De Wever, B., Waaramaa, T., Laukkanen, A.-M., & Lämsä, J. (2018). It’s not only what you say, but how you say it: Investigating the potential of prosodic analysis as a method to study teacher’s talk. Frontline Learning Research, 6(3), 204–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejji Alanazi, M. (2019). A study of the pre-service trainee teachers problems in designing lesson plans. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ), 10(1), 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofkens, T., Pianta, R. C., & Hamre, B. (2023). Teacher-student interactions: Theory, measurement, and evidence for universal properties that support students’ learning across countries and cultures. In Effective teaching around the world: Theoretical, empirical, methodological and practical insights (pp. 399–422). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeyr, A. S. (2022). Incorporating intercultural competence into EFL classrooms: The case of Japanese higher education institutions. In K. Hemmy, & C. Balasubramanian (Eds.), World englishes, global classrooms: The future of English literary and linguistic studies (pp. 115–130). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J., Greene, B., & Lowery, J. (2017). Multiple dimensions of teacher identity development from pre-service to early years of teaching: A longitudinal study. Journal of Education for Teaching, 43(1), 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. (2019). Introducing language and intercultural communication. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazempour, M. (2009). Impact of inquiry-based professional development on core conceptions and teaching practices: A case study. Science Educator, 18(2), 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Keiler, L. S. (2018). Teachers’ roles and identities in student-centered classrooms. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S. D., & Church, R. B. (1998). A comparison between children’s and adults’ ability to detect conceptual information conveyed through representational gestures. Child Development, 69(1), 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, M. (2021). Investigating connections between teacher identity and pedagogy in a content-based classroom. System, 100, 102551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D., Yuan, R., & Zou, M. (2024). Pre-service EFL teachers’ intercultural competence development within service-learning: A Chinese perspective. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 33(2), 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kövecses, Z. (2003). Metaphor and emotion: Language, culture, and body in human feeling. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kramsch, C. (2014). Language and culture. AILA Review, 27(1), 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramsch, C., & Whiteside, A. (2008). Language ecology in multilingual settings. Towards a theory of symbolic competence. Applied Linguistics, 29(4), 645–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, G. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G. (2011). Discourse analysis and education: A multimodal social semiotic approach. In An introduction to critical discourse analysis in education (pp. 205–226). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2002). Colour as a semiotic mode: Notes for a grammar of colour. Visual Communication, 1(3), 343–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Z., Wang, F., Xie, H., Mayer, R. E., & Hu, X. (2023). Effect of the instructor’s eye gaze on student learning from video lectures: Evidence from two three-level meta-analyses. Educational Psychology Review, 35(4), 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laadem, M., & Mallahi, H. (2019). Multimodal pedagogies in teaching English for specific purposes in higher education: Perceptions, challenges and strategies. International Journal on Studies in Education, 1(1), 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Hunter, J., & Franken, M. (2013). Story sharing in narrative research. Te Reo, 56/57, 145–159. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.674778551560186 (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Lee, Y.-J. (2019). Integrating multimodal technologies with VARK strategies for learning and teaching EFL presentation: An investigation into learners’ achievements and perceptions of the learning process. Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 2(1), 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. (2020). Sociocultural theory and teacher cognition. In Language teacher cognition: A sociocultural perspective (pp. 19–50). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. (2020). Multimodal pedagogy in TESOL teacher education: Students’ perspectives. System, 94, 102337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W., & Costa, P. I. D. (2018). Exploring novice EFL teachers’ identity development: A case study of two EFL teachers in China. In M. Sarah, & K. Achilleas (Eds.), Language teacher psychology (pp. 86–104). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddicoat, A. J., & Scarino, A. (2013). Intercultural language teaching and learning. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, F. V. (2020). Designing learning with embodied teaching: Perspectives from multimodality. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, F. V. (2024). The future of TESOL with multimodality. International Journal of TESOL Studies, 241213, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, F. V., Towndrow, P. A., & Min Tan, J. (2023). Unpacking the teachers’ multimodal pedagogies in the primary English language classroom in Singapore. RELC Journal, 54(3), 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, W. (2007). Communicative and task-based language teaching in East Asian classrooms. Language Teaching, 40(3), 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., Zhang, N., Chen, W., Wang, Q., Yuan, Y., & Xie, K. (2022). Categorizing teachers’ gestures in classroom teaching: From the perspective of multiple representations. Social Semiotics, 32(2), 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., & Trent, J. (2023). Being a teacher in China: A systematic review of teacher identity in education reform. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 22(4), 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Borg, S. (2014). Tensions in teachers’ conceptions of research: Insights from college English teaching in China. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 37(3), 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero-Babativa, E. (2024). The enactment of teacher-educator interactional identities in the classrooms of English language education. TESOL Journal, 15(2), e766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luguetti, C., Aranda, R., Nuñez Enriquez, O., & Oliver, K. L. (2019). Developing teachers’ pedagogical identities through a community of practice: Learning to sustain the use of a student-centered inquiry as curriculum approach. Sport, Education and Society, 24(8), 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, F., & Sun, J. (2023). Discussion on the application of contributing student pedagogy in vocational education “Computer network technology”. In Signal and information processing, networking and computers. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, P., & Godhe, A.-L. (2019). Multimodality in language education: Implications for teaching. Designs for Learning, 11(1), 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margutti, P., & Drew, P. (2014). Positive evaluation of student answers in classroom instruction. Language and Education, 28(5), 436–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariën, D., Vanderlinde, R., & Struyf, E. (2023). Teaching in a shared classroom: Unveiling the effective teaching behavior of beginning team teaching teams using a qualitative approach. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Álvarez, P., Cuevas, I., & Torres-Guzmán, M. (2017). Preparing bilingual teachers: Mediating belonging with multimodal explorations in language, identity, and culture. Journal of Teacher Education, 68(2), 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Lirola, M. (2016). The importance of promoting multimodal teaching in the foreign language classroom for the acquisition of social competences: Practical examples. International Journal for 21st Century Education, 3, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Matelau, T., & Sagapolutele, U. (2023). Constructing a hybrid Samoan identity through Siva Samoa in New Zealand: A multimodal (inter)action analysis of two dance rehearsals. Multimodal Communication, 12(1), 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, N., & Price, L. (2019). Identity formation among novice academic teachers—A longitudinal study. Studies in Higher Education, 44(6), 990–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Laguna, J. A. (2023). Critical learning episodes in the EFL classroom: A multimodal (inter)action analytical perspective. Multimodal Communication, 12(1), 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkova, S. (2012). Strategies for effective lesson planning. Center for Research on learning and Teaching, 1(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2019). ZHONGGUO jizhu jiaoyufazhan gaikuang [Brief introduction to basic education development in China]. Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-02/23/content_5367987.htm (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Mirzaei, A., Azizi Farsani, M., & Chang, H. (2023). Statistical learning of L2 lexical bundles through unimodal, bimodal, and multimodal stimuli. Language Teaching Research, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, T. (2018). Multimodal competence and effective interactive lecturing. System, 77, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, T. (2020). EMI teacher training with a multimodal and interactive approach: A new horizon for LSP specialists. Language Value, 12(1), 56–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, J. S. (2017). The importance of questioning in developing critical thinking skills. Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin, 84(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Nickel, J., & Zimmer, J. (2019). Professional identity in graduating teacher candidates. Teaching Education, 30(2), 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoladis, E., Aneja, A., Sidhu, J., & Dhanoa, A. (2022). Is there a correlation between the use of representational gestures and self-adaptors? Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 46(3), 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, S. (2004). Analyzing multimodal interaction: A methodological framework. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, S. (2009). Modal density and modal configurations: Multimodal actions. The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, S. (2011). Identity in (inter)action: Introducing multimodal (inter)action analysis. De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, S. (2013). What is a mode? Smell, olfactory perception, and the notion of mode in multimodal mediated theory. Journal Multimodal Communication, 2(2), 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, S. (2017). Scales of action: An example of driving and car talk in Germany and North America. Text & Talk, 37(1), 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, S. (2019). Systematically working with multimodal data: Research methods in multimodal discourse analysis. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, S. (2020). Multimodal theory and methodology: For the analysis of (inter)action and identity (p. 16). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, S., & Maier, C. D. (2014). Interactions, images and texts: A reader in multimodality (vol. 11). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuroh, E. Z., Munir, A., Retnaningdyah, P., & Purwati, O. (2020). Innovation in ELT: Multiliteracies pedagogy for enhancing critical thinking skills in the 21st century. Tell: Teaching of English Language and Literature Journal, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Halloran, K. L., Tan, S., Wiebrands, M., Sheffield, R., Wignell, P., & Turner, P. (2018). The multimodal classroom in the digital age: The use of 360 degree videos for online teaching and learning. In Multimodality across classrooms (pp. 84–102). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Q. (2014). Nonverbal teacher-student communication in the foreign language classroom. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 4(12), 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papen, U., & Peach, E. (2021). Picture books and critical literacy: Using multimodal interaction analysis to examine children’s engagements with a picture book about war and child refugees. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 44(1), 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z. (2015). Classroom discourse in college English teaching of China: A pedagogic or natural mode? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 36(7), 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J. E. (2019). The roles of multimodal pedagogic effects and classroom environment in willingness to communicate in English. System, 82, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z., Ye, Y., & Wang, Y. (2020). Investigating pre-service english teachers’ identity construction using multimodal discourse analysis. Advances in Educational Technology and Psychology, 4(1), 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Pennings, H. J. M., & Hollenstein, T. (2020). Teacher-student interactions and teacher interpersonal styles: A state space grid analysis. The Journal of Experimental Education, 88(3), 382–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, M. (2018). Intercultural citizenship education in the language classroom. In I. Davies, L.-C. Ho, D. Kiwan, C. L. Peck, A. Peterson, E. Sant, & Y. Waghid (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of global citizenship and education (pp. 489–506). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proweller, A., & Mitchener, C. P. (2004). Building teacher identity with urban youth: Voices of beginning middle school science teachers in an alternative certification program. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(10), 1044–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujadas, G., & Muñoz, C. (2020). Examining adolescents EFL learners’ TV viewing comprehension through captions and subtitles. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(3), 551–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y., & Wang, P. (2021). How EFL teachers engage students: A multimodal analysis of pedagogic discourse during classroom lead-ins. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 793495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmajanti, S., Sulistyo, G. H., Megawati, F., & Akbar, A. A. N. M. (2021). Professional identity construction of EFL teachers as autonomous learners. JEES (Journal of English Educators Society), 6(2), 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2014). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K. (2006). ‘Being the teacher’: Identity and classroom conversation. Applied Linguistics, 27(1), 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, K., & Bahari, A. (2022). Second language teacher identity: A systematic review. In K. Sadeghi, & F. Ghaderi (Eds.), Theory and practice in second language teacher identity: Researching, theorising and enacting (pp. 11–30). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, I. (2013). The role of self-confidence in learning to teach in higher education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 50(2), 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, K. R. (2003). Vocal communication of emotion: A review of research paradigms. Speech Communication, 40(1), 227–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollon, R. (1997). Discourse identity, social identity, and confusion in intercultural communication. Intercultural Communication Studies, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Scollon, R. (2002). Mediated discourse: The nexus of practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shank, M. J. (2006). Teacher storytelling: A means for creating and learning within a collaborative space. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(6), 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K., Alavi, H. S., Jermann, P., & Dillenbourg, P. (2016, April 25–29). A gaze-based learning analytics model: In-video visual feedback to improve learner’s attention in MOOCs. Sixth International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge, Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikveland, R. O., Solem, M. S., & Skovholt, K. (2021). How teachers use prosody to guide students towards an adequate answer. Linguistics and Education, 61, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahnke, R., & Blömeke, S. (2021). Novice and expert teachers’ situation-specific skills regarding classroom management: What do they perceive, interpret and suggest? Teaching and Teacher Education, 98, 103243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, G., & Tellier, M. (2022). Gesture helps second and foreign language learning and teaching. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C., Feng, X., Sun, B., Li, W., & Zhong, C. (2022). Teachers’ professional identity and burnout among Chinese female school teachers: Mediating roles of work engagement and psychological capital. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X., & Matsuda, P. K. (2020). Teacher beliefs and pedagogical practices of integrating multimodality into first-year composition. Computers and Composition, 58, 102614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y., & Hew, K. F. (2022). Effects of using mobile instant messaging on student behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement: A quasi-experimental study. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R. (2016). The multimodal texture of engagement: Prosodic language, gaze and posture in engaged, creative classroom interaction. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 20, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z., An, F., & Cui, Y. (2024). Exploring teacher discourse patterns: Comparative insights from novice and expert teachers in junior high school EFL contexts. Heliyon, 10(16), e36435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, J. (2011). ‘Four years on, I’m ready to teach’: Teacher education and the construction of teacher identities. Teachers and Teaching, 17(5), 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, J. (2016). Constructing professional identities in shadow education: Perspectives of private supplementary educators in Hong Kong. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 15(2), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C. S., Behoora, I., Nembhard, H. B., Lewis, M., Sterling, N. W., & Huang, X. (2015). Machine learning classification of medication adherence in patients with movement disorders using non-wearable sensors. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 66, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaish, V., & Towndrow, P. A. (2010). 12. Multimodal literacy in language classrooms. In H. H. Nancy, & M. Sandra Lee (Eds.), Sociolinguistics and language education (pp. 317–346). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Branden, K. (2006). Task-based language education: From theory to practice. Language, 53(82), T35. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lankveld, T., Schoonenboom, J., Volman, M., Croiset, G., & Beishuizen, J. (2017). Developing a teacher identity in the university context: A systematic review of the literature. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(2), 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, T. (2021). Multimodality and identity. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, M., Morgan, B., Johnston, B., & Johnson, K. A. (2005). Theorizing language teacher identity: Three perspectives and beyond. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 4(1), 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veliz, L., Picard, M., & Farias, M. (2024). Reimagining literacies pedagogy in the twenty-first century: Theorizing and enacting multiple literacies for english language learners. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K., & Yuan, R. (2024). Incorporating critical pedagogy into second language teacher education: An identity lens. RELC Journal, 56(1), 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., Yuan, R., & Lee, I. (2024). Exploring contradiction-driven language teacher identity transformation during curriculum reforms: A Chinese tale. TESOL Quarterly, 58(4), 1548–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasik, B. A., & Bond, M. A. (2001). Beyond the pages of a book: Interactive book reading and language development in preschool classrooms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(2), 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigham, C. R., & Satar, M. (2024). Adapting and extending multimodal (inter)action analysis to investigate synchronous multimodal online language teaching. Multimodal Communication, 13(3), 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilford, M. M., Kurpad, N., Platt, M., & Weinstein-Jones, Y. (2020). Lecturer fluency can impact students’ judgments of learning and actual learning performance. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(6), 1444–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmes, S. E., & Siry, C. (2021). Multimodal interaction analysis: A powerful tool for examining plurilingual students’ engagement in science practices: Proposed contribution to rise special issue: Analyzing science classroom discourse. Research in Science Education, 51(1), 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. (2023). Reflexivity in multilingual and intercultural education: Chinese international secondary school students’ critical thinking. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 44(1), 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q. (2017). Investigating the target language usage in and outside business English classrooms for non-English major undergraduates at a Chinese university. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1415629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. (2014). An investigation into university novice foreign language teachers’ professional development: The participant teachers’ perspective. Journal of PLA University of Foreign Language, 37(04), 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Xun, Y., & Zheng, X. (2014). A review of the studies on EFL teachers’ identity in the past decade. Modern Foreign Languages (Bimonthly), 37(1), 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (vol. 5). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L. (2024). EFL teacher-student interaction, teacher immediacy, and Students’ academic engagement in the Chinese higher learning context. Acta Psychologica, 244, 104185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R., & Mak, P. (2018). Reflective learning and identity construction in practice, discourse and activity: Experiences of pre-service language teachers in Hong Kong. Teaching and Teacher Education, 74, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R., & Zhang, L. J. (2020). Teacher metacognitions about identities: Case studies of four expert language teachers in China. TESOL Quarterly, 54(4), 870–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M. M., Ritonga, M., & Kumar, T. (2022). Multimodal teaching practices for EFL teacher education: An action based research study. Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, 13, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. (2023). The influence of test-oriented teaching on Chinese students’ long-term use of English. International Journal of Education and Humanities, 6(2), 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., & Gu, Y. (2024, July 26–29). The impact of teachers’ multimodal cues on students’ L2 vocabulary learning in naturalistic classroom teaching. Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Sydney, NSW, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y., & Zhang, J. (2016). Academic development of young university teachers of foreign languages: A case study. Shandong Foreign Language Teaching, 37, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C. (2010). Teacher perceptions of their roles and adoption of educational technology: Challenges in the chinese context. Educational Technology, 50(6), 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhukova, O. (2018). Novice teachers’ concerns, early professional experiences and development: Implications for theory and practice. Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education, 9(1), 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, D. H. (1998). Identity, context and interaction. In C. Antaki, & S. Widdicombe (Eds.), Identities in talk (pp. 87–106). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

| Total Modal Shifts | Teacher A S1 | Teacher A S3 | Teacher BS1 | Teacher BS3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teachers’ talk time | 9 min (mostly lecture) | 6 min (more dialogue) | 6 min (3 min playing listening recording) | 5 min (more peer discussion) |

| Student-directed gaze | 2 | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| Gesture (self-adaptors excluded) | 3 | 10 | 2 | 12 |

| Feedback moves | 0 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Open question | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Students’ response | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, J.; Li, C.; Cheng, Y. Transforming Pedagogical Practices and Teacher Identity Through Multimodal (Inter)action Analysis: A Case Study of Novice EFL Teachers in China. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081050

Zhou J, Li C, Cheng Y. Transforming Pedagogical Practices and Teacher Identity Through Multimodal (Inter)action Analysis: A Case Study of Novice EFL Teachers in China. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081050

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Jing, Chengfei Li, and Yan Cheng. 2025. "Transforming Pedagogical Practices and Teacher Identity Through Multimodal (Inter)action Analysis: A Case Study of Novice EFL Teachers in China" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081050

APA StyleZhou, J., Li, C., & Cheng, Y. (2025). Transforming Pedagogical Practices and Teacher Identity Through Multimodal (Inter)action Analysis: A Case Study of Novice EFL Teachers in China. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081050