A Physiological Approach to Vocalization and Expanding Spoken Language for Adolescents with Selective Mutism

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Treatment Considerations

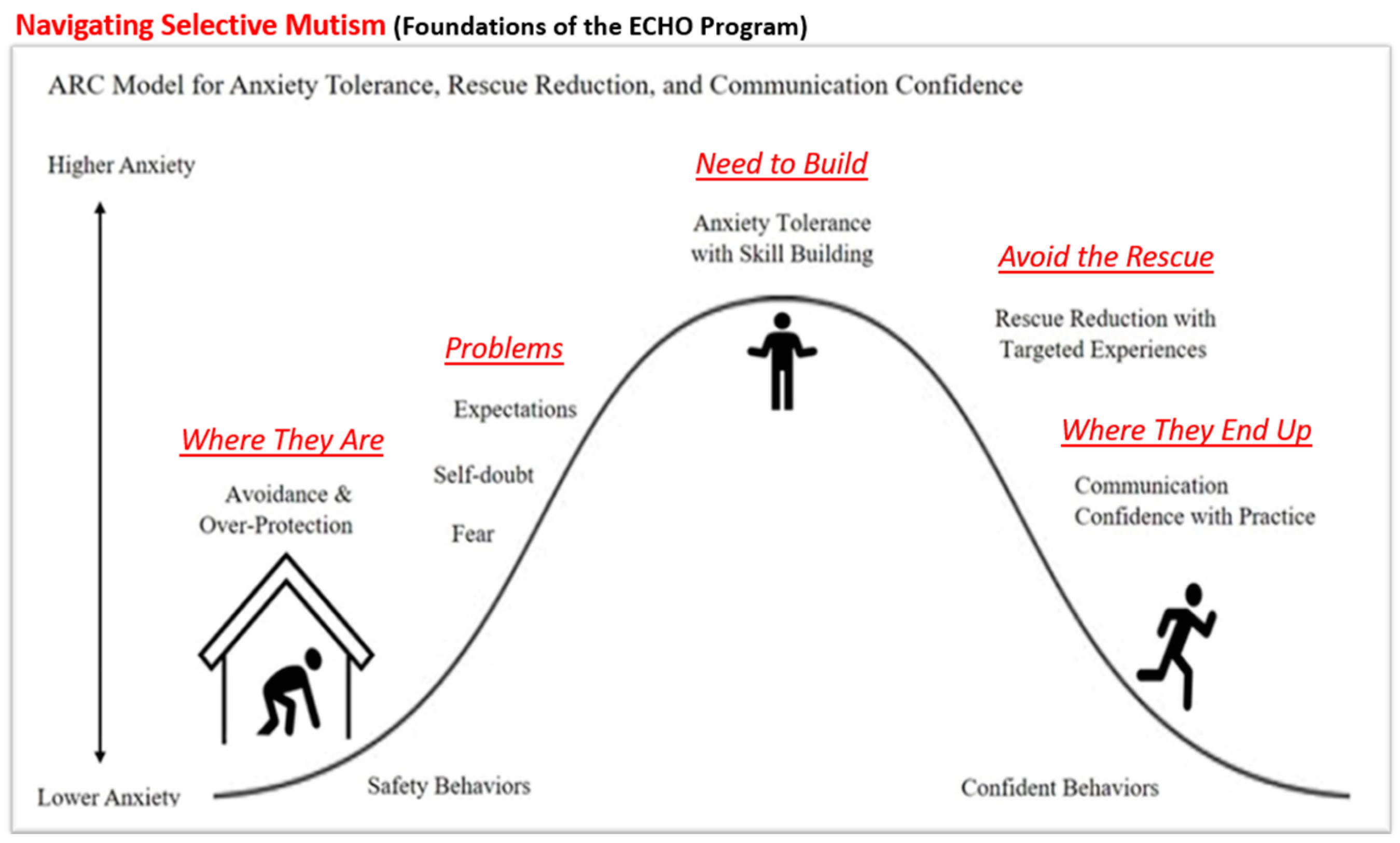

1.2. Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Case 1: GB

2.1.2. Case 2: KD

2.2. Measures

2.3. Design

2.4. Procedures

2.4.1. Treatment Module Procedures

- Sound Off: To increase awareness of nasal, oral, and throat speech sound production; to increase awareness of voicing and distinctive features (nasal/oral/throat, airflow continuation or stop, voice vibration or no vibration) for speech sound production; to increase awareness of articulatory contacts (lips, teeth, palate, tongue, or glottal) for speech sound production; and to identify voicing and distinctive features for speech sound production in words.

- Pitch Pipe: To demonstrate vocal control for pitch variation spontaneously and on demand and to discuss the concept of high and low voices by demonstrating the differences.

- Ramp it up: To demonstrate vocal control for loudness variation spontaneously and on demand and to discuss the concept of loud and soft voice by demonstrating the differences.

- Vocal Marathon: To discuss the concept of freeing the voice via easy voice onset from humming /m/ and/or /h/ initiated words to speech and to increase vocal ability to sustain the voice for 5–10 s, as able.

- Tag Along Words: To demonstrate the carry-over of skills by generating words from random sounds.

- What’s Up: To use learned strategies to initiate speech in response to questions.

- Let’s Face it: To label, identify, imitate, and express emotions. After working on vocal control and speech production, the individuals were able to initiate their voice and answer basic questions using spoken language. The next section utilized vocal control methods to gain knowledge and experience of pragmatic language and increase the ability to use language for different purposes, change language depending on the situation, and engage in conversation.

- Word Think: To say a word spontaneously without lengthy pausing or hesitation

- Pinpoint: To say what comes to mind spontaneously, take turns speaking, and formulate sentences on a topic.

- Actor’s Corner—Interactive Scripts: To use intonation and vocal expression, engage in dialogue with turn-taking and topic maintenance, and increase communicative interactions with scripted conversation.

- Barriers: To increase listening skills, increase direction-giving skills, request clarification, and help reduce possible perfectionistic tendencies.

- Question Match—Answering Questions: To provide or request information (yes-no and wh-questions); to engage in turn-taking and question-answer routines; and to give sufficient information for listener comprehension and interactions.

- More Information Please—Changing Questions: To ask questions with intonation and vocal expression; to listen when another person speaks; to take turns asking and answering questions; and to provide a follow-up comment after the other person answers the question.

- See-Saw—Keep the Conversation Going: To engage in turn-taking during a conversation; to ask/answer yes-no and wh-questions; and to make comments during a conversation (state an opinion or feeling, agree or disagree, provide information or instructions, state an intent, provide clarification, make a prediction, provide a reason, and offer a suggestion).

- Road Runner—Staying on Topic Track: To maintain a topic or related topics; to stay focused and give information for listener comprehension and interaction; and to engage in a two-way conversation with turn-taking.

- Conversation Wheelhouse: To attend to stories read aloud with pictures and to share information and interact using the following conversational skills (retelling, questioning, answering, commenting, sharing information, telling a story/relating an event, agreeing, and disagreeing).

- Conversational Role-Plays: Pragmatic Language: To increase the use of pragmatic language skills found in daily conversations and interactions (greeting, farewells, opening and closing a conversation, showing appreciation, commenting, complimenting, apologizing, requesting clarification or information, stating a problem, making an excuse, complaining, asking for help, offering to help, and providing information).

- Chat Spin—Informal Conversations: To increase conversational skills by taking turns listening and speaking, keeping the conversation going with questions, answers, and comments; to share experiences, thoughts, and opinions; to use expression in one’s voice; and to smile or act interested in what another person says.

2.4.2. Detailed Case Treatment and Progress

Case 1: GB

- GB—Vocal Control

- GB—Pragmatic Language

Case 2: KD

- KD—Vocal Control

- KD—Pragmatic Language

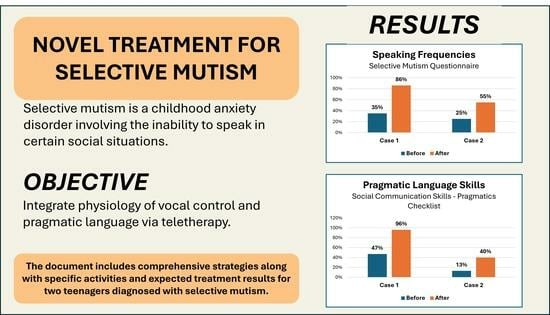

3. Results

3.1. Case 1—GB’s Treatment Outcomes

3.2. Case 2—KD’s Treatment Outcomes

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- Early Detection and Intervention: Early recognition of SM and timely intervention are critical in preventing long-term anxiety disorders and communication impairments.

- Multifaceted Therapeutic Approach: An integrated treatment plan addressing both vocal control and pragmatic language skills is essential for effective therapy.

- Individualized Treatment Plans: Tailoring interventions to the unique needs and abilities of each child, especially those with comorbid conditions, enhances therapeutic outcomes.

- Gradual Exposure and Outreach: Gradual exposure to challenging communicative situations fosters confidence and reduces anxiety.

- Parental Support and Engagement: Consistent involvement and support from parents are crucial in reinforcing therapeutic gains.

- Generalization of Skills: Encouraging the generalization of communicative skills across different settings and interactions is key to long-term success.

- Motivating and Engaging Activities: Strategic rewards for accomplishing interactive, meaningful activities that resonate with the child’s interests, enhance engagement, and help facilitate skill acquisition.

Limitations, Barriers, and Future Directions

- Case reports offer valuable clinical perspectives; however, there are limitations that restrict their broader applicability. The reliance on two individual case studies limits the generalizability of the findings. The results observed in GB and KD may not be representative of the wider population of children and adolescents with SM, although they show various progress profiles. The cases primarily focus on teenagers. There is a need to explore the efficacy of this vocal control-pragmatic language intervention across a broader age range, including younger children (beginning with those in upper elementary grades) and older adolescents (up to 21 years of age). Additionally, without a control or comparison group, it is difficult to attribute improvements solely to the intervention, as spontaneous improvement or external factors cannot be excluded. Clinical observations and outcomes in case reports are susceptible to subjective bias, as they may reflect the interpretations and expectations of the clinician or client. While progress has been documented for more than a year, long-term outcomes and maintenance of communicative gains remain unverified over the long term.

- Families seeking effective therapeutic interventions for children with SM face various barriers that can limit treatment success. For young children, developmental readiness may be of concern, as short attention spans and limited comprehension can reduce the effectiveness of structured therapy, especially when delivered virtually. Although technology provides opportunities for remote access, it may not be available to everyone. Not all families have reliable Internet, appropriate devices, or the skills needed to fully engage in virtual treatment. Family involvement is a critical factor. Inconsistent support at home, combined with cultural or language mismatches between families and providers, can weaken the treatment outcomes. Children themselves vary widely in their needs and responsiveness. Those with co-occurring conditions, such as autism or anxiety, may require alternative approaches. External barriers, such as the limited availability of qualified specialists, insurance restrictions, and scheduling conflicts, can make access to care even more challenging. Additionally, the skills and experience of the therapist are essential. Together, these challenges highlight the need for flexible and personalized treatment plans. Successful interventions must consider each child’s developmental level, home environment, cultural background, and emotional readiness.

- By systematically addressing these limitations and barriers, future work may provide a comprehensive and reliable understanding of effective long-term SM interventions. This will ultimately inform best practices and improve outcomes for children, teenagers, and families navigating SM.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Belyk, M., & Brown, S. (2017). The origins of the vocal brain in humans. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 77, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, R. L., Keller, M. L., Piancentini, J., & Bergman, A. J. (2008). The development and psychometric properties of the selective mutism questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(2), 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birmaher, B., Khetarpal, S., Brent, D., Cully, M., Balach, L., Kaufman, J., & Neer, S. M. (1997). The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(4), 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, B., Edgar, V. B., Bar, S. H., Call, C. R., & Nyp, S. S. (2025). Selective mutism in the context of autism and bilingualism. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 46(1), e87–e89. [Google Scholar]

- Driessen, J., Blom, J. D., Muris, P., Blashfield, R. K., & Molendijk, M. L. (2020). Anxiety in children with selective mutism: A meta-analysis. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 51, 330–341. [Google Scholar]

- Goberis, D., Beams, D., Dalpes, M., Abrisch, A., Baca, R., & Yoshinaga-Itano, C. (2012). The missing link in language development: Social communication development. Seminars in Speech and Language, 33(4), 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, A., & Major, N. (2016). Selective mutism. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 28, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E. R., & Armstrong, S. L. (2015). Express selective mutism communication questionnaire—Child. Available online: https://www.selectivemutism.org/resources/archive/online-library/express-selective-mutism-sm-communication-questionnaire/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Klein, E. R., Armstrong, S. L., & Shipon-Blum, E. (2013). Assessing spoken language competence in children with selective mutism: Using parents as test presenters. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 34, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E. R., Chesney, C. E., & Ruiz, C. E. (2021). The ARC model for anxiety tolerance, rescue reduction, and communication confidence. In ECHO: A vocal language program for easing anxiety in conversation. Plural Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Koskela, M., Ståhlberg, T., Yunus, W. M. A. W. M., & Sourander, A. (2023). Long-term outcomes of selective mutism: A systematic literature review. BMC Psychiatry, 23, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlowska, K., Walker, P., McLean, L., & Carrive, P. (2015). Fear and the defense cascade: Clinical implications and management. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 23(4), 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manassis, K., Oerbeck, B., & Overgaard, K. R. (2016). The use of medication in selective mutism: A systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25, 571–578. [Google Scholar]

- Milic, M. I., Carl, T., & Rapee, R. M. (2023). Understanding selective mutism: A comprehensive guide to assessment and treatment. In Handbook of clinical child psychology: Integrating theory and research into practice (pp. 1107–1125). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Muris, P., Hendriks, E., & Bot, S. (2016). Children of few words: Relations among selective mutism, behavioral inhibition, and (social) anxiety symptoms in 3- to 6-year-olds. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 47(1), 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muris, P., & Ollendick, T. H. (2015). Children who are anxious in silence: A review on selective mutism, the new anxiety disorder in DSM-5. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18(2), 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muris, P., & Ollendick, T. H. (2021). Selective mutism and its relations to social anxiety disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 24(2), 294–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oerbeck, B., Manassis, K., Overgaard, K. R., & Kristensen, H. (2019). Selective mutism. In J. M. Rey, & A. Martin (Eds.), JM Rey’s IACAPAP e-textbook of child and adolescent mental health. International Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions. [Google Scholar]

- Oerbeck, B., Stein, M. B., Wentzel-Larsen, T., Langsrud, Ø., & Kristensen, H. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of a home and school-based intervention for selective mutism–defocused communication and behavioural techniques. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 19(3), 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Østergaard, K. R. (2018). Treatment of selective mutism based on cognitive behavioural therapy, psychopharmacology and combination therapy—A systematic review. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 72(4), 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues Pereira, C., Ensink, J. B., Güldner, M. G., Lindauer, R. J., De Jonge, M. V., & Utens, E. M. (2023). Diagnosing selective mutism: A critical review of measures for clinical practice and research. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(10), 1821–1839. [Google Scholar]

- Rozenek, E. B., Orlof, W., Nowicka, Z. M., Wilczyńska, K., & Waszkiewicz, N. (2020). Selective mutism-an overview of the condition and etiology: Is the absence of speech just the tip of the iceberg? Psychiatria Polska, 54(2), 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, C. E., & Klein, E. R. (2013). Effects of anxiety on voice production: A retrospective case report of selective mutism. PSHA Journal, 19–26. Available online: https://www.psha.org/about-psha/pdf/PSHAJournal-2013.pdf#page=19 (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Ruiz, C. E., & Klein, E. R. (2018). Surface electromyography to identify laryngeal tension in selective mutism: Could this be the missing link? Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research, 12(2), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, C. E., Klein, E. R., & Chesney, L. R. (2022). ECHO: A vocal language program for easing anxiety in conversation. Plural Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenck, C., Gensthaler, A., & Vogel, F. (2021). Anxiety levels in children with selective mutism and social anxiety disorder. Current Psychology, 40(12), 6006–6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J., Fu, Y., Ren, Z., Zhang, T., Du, M., Gong, Q., Lui, S., & Zhang, W. (2014). The common traits of the ACC and PFC in anxiety disorders in the DSM-5: Meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. PLoS ONE, 9(3), e93432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonyan, K., & Horwitz, B. (2011). Laryngeal motor cortex and control of speech in humans. The Neuroscientist, 17(2), 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffenburg, H., Steffenburg, S., Gillberg, C., & Billstedt, E. (2018). Children with autism spectrum disorders and selective mutism. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T., Takeda, A., Takadaya, Y., & Fujii, Y. (2020). Examining the relationship between selective mutism and autism spectrum disorder. Asian Journal of Human Services, 19, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udy, C. M., Newall, C., Broeren, S., & Hudson, J. L. (2014). Maternal expectancy versus objective measures of child skill: Evidence for absence of positive bias in mothers’ expectations of children with internalizing disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(3), 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, F., Reichert, J., & Schwenck, C. (2022). Silence and related symptoms in children and adolescents: A network approach to selective mutism. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakszeski, B. N., & DuPaul, G. J. (2017). Reinforce, shape, expose, and fade: A review of treatments for selective mutism (2005–2015). School Mental Health, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SMQ Settings | Pretest Completed by Mother | Post-Test Completed by Mother | Post-Test Completed by GB |

|---|---|---|---|

| School (3-point scale.) | 1.33 (44.3%) | 2.83 (94.3%) | 2.5 (83.3) |

| Family (3-point scale) | 1.4 (46.7%) | 2.83 (94.3%) | 2.67 (89%) |

| Social Situations (3-point scale) | 0.6 (20%) | 2.0 (66.7%) | 2.4 (80%) |

| Total Points (based on 17 items 3 points possible for each = 51 | 18/51 (35.3%) | 44/51 (86.3%) | 43/51 (84.3) |

| Pragmatic Categories | Pre (Completed by Parents) | Post (Completed by Parents) |

|---|---|---|

| Stating Needs | 8/15 (53%) | 15/15 (100%) |

| Giving Directions | 5/9 (56%) | 8/9 (89%) |

| Expressing Feelings | 15/21 (71%) | 21/21 (100%) |

| Interacting | 17/45 (38%) | 43/45 (96%) |

| Asking Questions | 7/15 (47%) | 14/15 (93%) |

| Sharing Knowledge/Thoughts | 11/30 (37%) | 29/30 (97%) |

| Total | 63/135 (46.7%) | 130/135 (96.3%) |

| SMQ Settings | Pretest Completed by Mother | Post-Test Completed by Mother | Post-Test Completed by KD |

|---|---|---|---|

| At School | 1.33 (44.3%) | 1.83 (61%) | 1.5 (50%) |

| With Family | 0.66 (22%) | 0.83 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) |

| In Social Situations | 0.2 (6.7%) | 0.6 (20%) | 1.8 (60%) |

| Total Points | 13/51 (25.5%) | 19/51 (37.3%) | 28/51 (54.9%) |

| Pragmatic Categories | Pre (Completed by Mother) | Post (Completed by Mother) |

|---|---|---|

| Stating Needs | 6/15 (40%) | 11/15 (73%) |

| Giving Directions | 0/9 (0%) | 3/9 (33%) |

| Expressing Feelings | 2/21 (9.5%) | 7/21 (33%) |

| Interacting | 2/45 (4%) | 21/45 (46%) |

| Asking Questions | 0/15 (0%) | 2/15 (13%) |

| Sharing Knowledge/Thoughts | 8/30 (26%) | 10/30 (33%) |

| Total | 18/135 (13.3%) | 54/135 (40%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klein, E.R.; Ruiz, C.E. A Physiological Approach to Vocalization and Expanding Spoken Language for Adolescents with Selective Mutism. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081013

Klein ER, Ruiz CE. A Physiological Approach to Vocalization and Expanding Spoken Language for Adolescents with Selective Mutism. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081013

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlein, Evelyn R., and Cesar E. Ruiz. 2025. "A Physiological Approach to Vocalization and Expanding Spoken Language for Adolescents with Selective Mutism" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081013

APA StyleKlein, E. R., & Ruiz, C. E. (2025). A Physiological Approach to Vocalization and Expanding Spoken Language for Adolescents with Selective Mutism. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081013