Do “Flops” Enhance Authenticity? The Impact of Influencers’ Proactive Disclosures of Failures on Product Recommendations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Influencer Self-Disclosure Strategy: Failure Disclosure

2.2. The Mediating Role of Perceived Authenticity

2.3. The Moderating Role of Observer Self-Discrepancy

2.4. The Moderating Role of Influencer Type

3. Methodology

4. Study 1

4.1. Design

4.2. Procedure

4.3. Measures

4.4. Results

4.5. Discussion

5. Study 2

5.1. Design

5.2. Procedure

5.3. Measures

5.4. Results

5.5. Discussion

6. Study 3

6.1. Design

6.2. Procedure

6.3. Measures

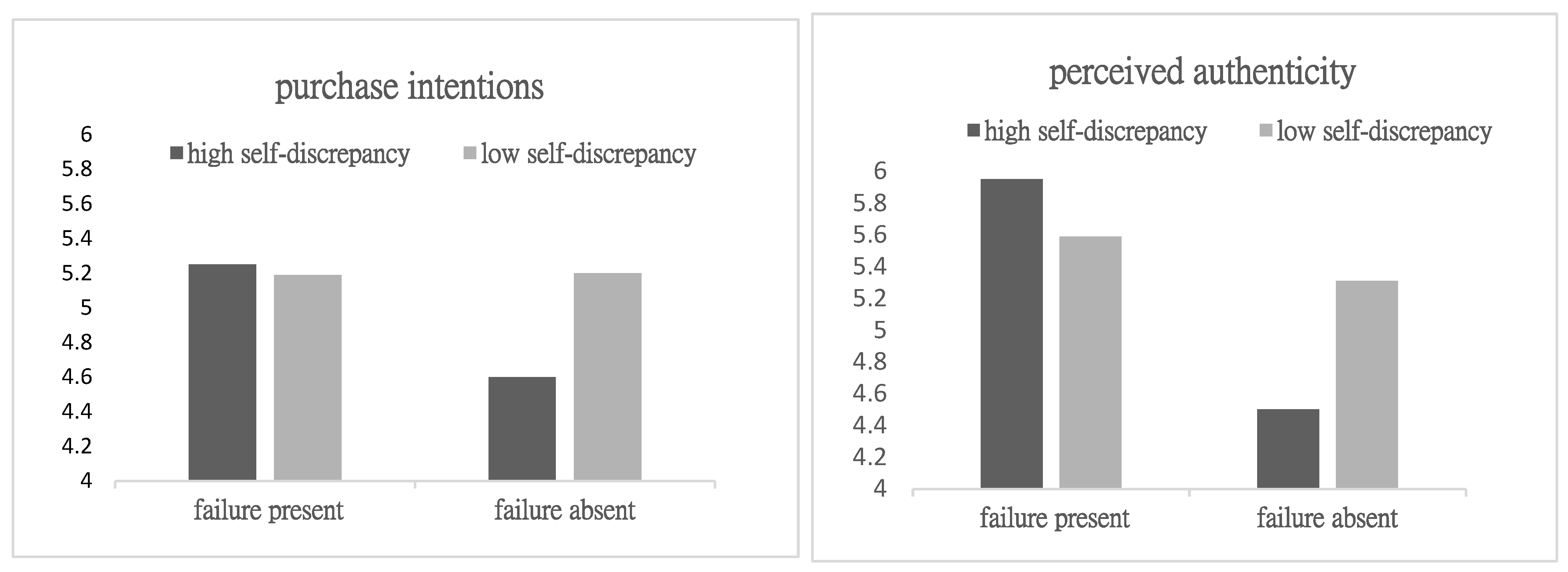

6.4. Results

6.5. Discussion

7. General Discussion

7.1. Key Findings

7.2. Theoretical Implications

7.3. Practical Implications

7.4. Limitations and Future Directions for Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Aronson, E., Willerman, B., & Floyd, J. (1966). The effect of a pratfall on increasing interpersonal attractiveness. Psychonomic Science, 4(6), 227–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrezet, A., de Kerviler, G., & Moulard, J. G. (2020). Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. Journal of Business Research, 117, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, E. C.-X., & Chuah, S. H. W. (2021). Stop the unattainable ideal for an ordinary me! fostering parasocial relationships with social media influencers: The role of selfdiscrepancy. Journal of Business Research, 132, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A. W., Huang, K., Abi-Esber, N., Buell, R. W., Huang, L., & Hall, B. (2019). Mitigating malicious envy: Why successful individuals should reveal their failures. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(4), 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L., Yan, Y., & Smith, A. N. (2023). What drives digital engagement with sponsored videos? An investigation of video influencers’ authenticity management strategies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 51(1), 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J., Ding, Y., & Kalra, A. (2023). I really know you: How influencers can increase audience engagement by referencing their close social ties. Journal of Consumer Research, 50(4), 683–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S., & Cho, H. (2017). Fostering parasocial relationships with celebrities on social media: Implications for celebrity endorsement. Psychology & Marketing, 34(4), 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, R., & Casais, B. (2023). Micro, macro and mega-influencers on instagram: The power of persuasion via the parasocial relationship. Journal of Business Research, 158, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrick, J. L., Gabriel, S., & Tippin, B. (2008). Parasocial relationships and self-discrepancies: Faux relationships have benefits for low self-esteem individuals. Personal Relationships, 15(2), 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36(5), 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, A., Schakenraad, R., Menninga, K., Buunk, A. P., & Siero, F. (2009). Self-discrepancies and involvement moderate the effects of positive and negative message framing in persuasive communication. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 31(3), 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R., Acikgoz, F., & Du, H. (2023). Electronic word-of-mouth from video bloggers: The role of content quality and source homophily across hedonic and utilitarian products. Journal of Business Research, 160, 113774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S., & Eckhardt, G. M. (2019). Putting the person back in person-brands: Understanding and managing the two-bodied brand. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(4), 602–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, B. M., & Kernis, M. H. (2002). The role of authenticity in healthy psychological functioning and subjective well-being. Annals of the American Psychotherapy Association, 5(6), 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Helmreich, R., Aronson, E., & LeFan, J. (1970). To err is humanizing sometimes: Effects of self-esteem, competence, and a pratfall on interpersonal attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 16(2), 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, E. T. (1989). Self-discrepancy theory: What patterns of self-beliefs cause people to suffer? Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 22, 93–136. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, A. K., Vemireddy, V., & Angeli, F. (2024). Social media “stars” vs “the ordinary” me: Influencer marketing and the role of self-discrepancies, perceived homophily, authenticity, self-acceptance and mindfulness. European Journal of Marketing, 58(2), 590–631. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L., John, L. K., Boghrati, R., & Kouchaki, M. (2022). Fostering perceptions of authenticity via sensitive self-disclosure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 28(4), 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y., & Lei, J. (2025). Will recommend a salad but choose a burger for you: The effect of decision tasks and social distance on food decisions for others. Journal of Applied Business & Behavioral Sciences, 1(1), 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernis, M. H., & Goldman, B. M. (2006). A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 283–357. [Google Scholar]

- Ki, C. W. C., & Kim, Y. K. (2019). The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Psychology & Marketing, 36(10), 905–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klostermann, J., Meißner, M., Max, A., & Decker, R. (2023). Presentation of celebrities’ private life through visual social media. Journal of Business Research, 156, 113524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. J., Lee, H. Y., & Choi, S. (2020). Is the message the medium? How politicians’ Twitter blunders affect perceived authenticity of Twitter communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. S., & Johnson, B. K. (2022). Are they being authentic? The effects of self-disclosure and message sidedness on sponsored post effectiveness. International Journal of Advertising, 41(1), 30–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, F. P., & de Baptista, P. P. (2022). Influencers’ intimate self-disclosure and its impact on consumers’ self-brand connections: Scale development, validation, and application. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 16(3), 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X., Aw, E. C. X., & Filieri, R. (2023). From screen to cart: How influencers drive impulsive buying in livestreaming commerce? Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 18(6), 1034–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malär, L., Herzog, D., Krohmer, H., Hoyer, W. D., & Kähr, A. (2018). The Janus face of ideal self-congruence: Benefits for the brand versus emotional distress for the consumer. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 3(2), 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munnukka, J., Uusitalo, O., & Toivonen, H. (2016). Credibility of a peer endorser and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(3), 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J. C., Ordanini, A., & Giambastiani, G. (2021). The concept of authenticity: What it means to consumers. Journal of Marketing, 85(4), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, M. L., Centeno, E., & Cambra-Fierro, J. (2020). A thematic exploration of human brands: Literature review and agenda for future research. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29(6), 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M., Blut, M., Ghiassaleh, A., & Lee, Z. W. (2024). Influencer marketing effectiveness: A meta-analytic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 53, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, J. W., Dahl, A. J., Drury, L., & Khan, T. (2024). Cutting-edge research in social media and interactive marketing: A review and research agenda. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 18(5), 900–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, M., Schroeder, J., & Gino, F. (2020). Tell it like it is: When politically incorrect language promotes authenticity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(1), 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarial-Abi, G., Ulqinaku, A., & Mokarram-Dorri, S. (2021). Living with restrictions: The duration of restrictions influences construal levels. Psychology & Marketing, 38(12), 2271–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L., & Verspaget, M. (2020). Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and ProductEndorser fit. International Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P., Nie, X., & Tong, C. (2025). Does disclosing commercial intention benefit brands? Mediating role of perceived manipulative intent and perceived authenticity in influencer hidden advertising. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 19(4), 673–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steils, N., Martin, A., & Toti, J. F. (2022). Managing the transparency paradox of social-media influencer disclosures: How to improve authenticity and engagement when disclosing influencer–sponsor relationships. Journal of Advertising Research, 62(2), 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D. T., Mai, N. Q., Nguyen, L. T., Thuan, N. H., Dang-Pham, D., & Hoang, A. P. (2024). Examining authenticity on digital touchpoint: A thematic and bibliometric review of 15 years’ literature. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. L. (2024). Editorial–what is an interactive marketing perspective and what are emerging research areas? Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 18(2), 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. L. (2025a). Basic but frequently overlooked issues in manuscript submissions: Tips from an editor’s perspective. Journal of Applied Business & Behavioral Sciences, 1(2), 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. L. (2025b). Editorial: Demonstrating contributions through storytelling. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 19(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., & Carlson, B. D. (2024). Self-disclosure of influencers: A systematic review and holistic framework. AMS Review, 14(3), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Mao, H., Li, Y. J., & Liu, F. (2017). Smile big or not? Effects of smile intensity on perceptions of warmth and competence. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(5), 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wies, S., Bleier, A., & Edeling, A. (2023). Finding goldilocks influencers: How follower count drives social media engagement. Journal of Marketing, 87(3), 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The authentic personality: A theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the authenticity scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(3), 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 2(3), 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Li, X., Wu, B., Zhou, L., & Chen, X. (2023). Order matters: Effect of use versus outreach order disclosure on persuasiveness of sponsored posts. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 17(6), 865–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Mercado, T., & Bi, N. C. (2025). “Unintended” marketing through influencer vlogs: Impacts of interactions, parasocial relationships and perceived influencer credibility on purchase behaviors. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 19(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental Situation | Experimental Purpose | Hypotheses Tested | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 (N = 94) | Real influencer (“Miao Er Ge”) | Main effect Mediating effect | H1 H2 | Yes Yes |

| Study 2 (N = 238) | Real influencer (“AWan”) | Moderating effect (observer self-discrepancy) | H1 H2 H3a H3b | Yes Yes Yes Yes |

| Study 3 (N= 238) | Fictional influencer (“dailydrunk”) | Moderating effect (influencer follower scale) | H1 H2 H4a H4b | Yes Yes Yes No |

| Bootstrapping | BC 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| Indirect effect | −0.476 | 0.014 | −0.824 | −0.242 |

| Direct effect | −0.0002 | 0.019 | −0.382 | 0.382 |

| Bootstrapping | BC 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| Indirect effect | 0.458 | 0.010 | −0.704 | −0.274 |

| Direct effect | 0.185 | 0.012 | −0.048 | 0.419 |

| Bootstrapping | BC 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| High self-discrepancy | −0.829 | 0.016 | −1.184 | −0.528 |

| Low self-discrepancy | −0.150 | 0.013 | −0.346 | 0.016 |

| Bootstrapping | BC 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| Indirect effect | −0.674 | 0.011 | −0.909 | −0.470 |

| Direct effect | 0.292 | 0.016 | −0.029 | 0.613 |

| Bootstrapping | BC 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| Macro-influencer | −0.798 | 0.016 | −1.144 | −0.532 |

| Micro-influencer | −0.579 | 0.012 | −0.856 | −0.360 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, X.; Li, C. Do “Flops” Enhance Authenticity? The Impact of Influencers’ Proactive Disclosures of Failures on Product Recommendations. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 971. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070971

Ye X, Li C. Do “Flops” Enhance Authenticity? The Impact of Influencers’ Proactive Disclosures of Failures on Product Recommendations. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):971. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070971

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Xinge, and Chunqing Li. 2025. "Do “Flops” Enhance Authenticity? The Impact of Influencers’ Proactive Disclosures of Failures on Product Recommendations" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 971. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070971

APA StyleYe, X., & Li, C. (2025). Do “Flops” Enhance Authenticity? The Impact of Influencers’ Proactive Disclosures of Failures on Product Recommendations. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 971. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070971