Does Control-Related Information Attenuate Biased Self-Control and Moral Perceptions Based on Weight?

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Current Work

2. Study 1

2.1. Method

2.2. Procedure and Materials

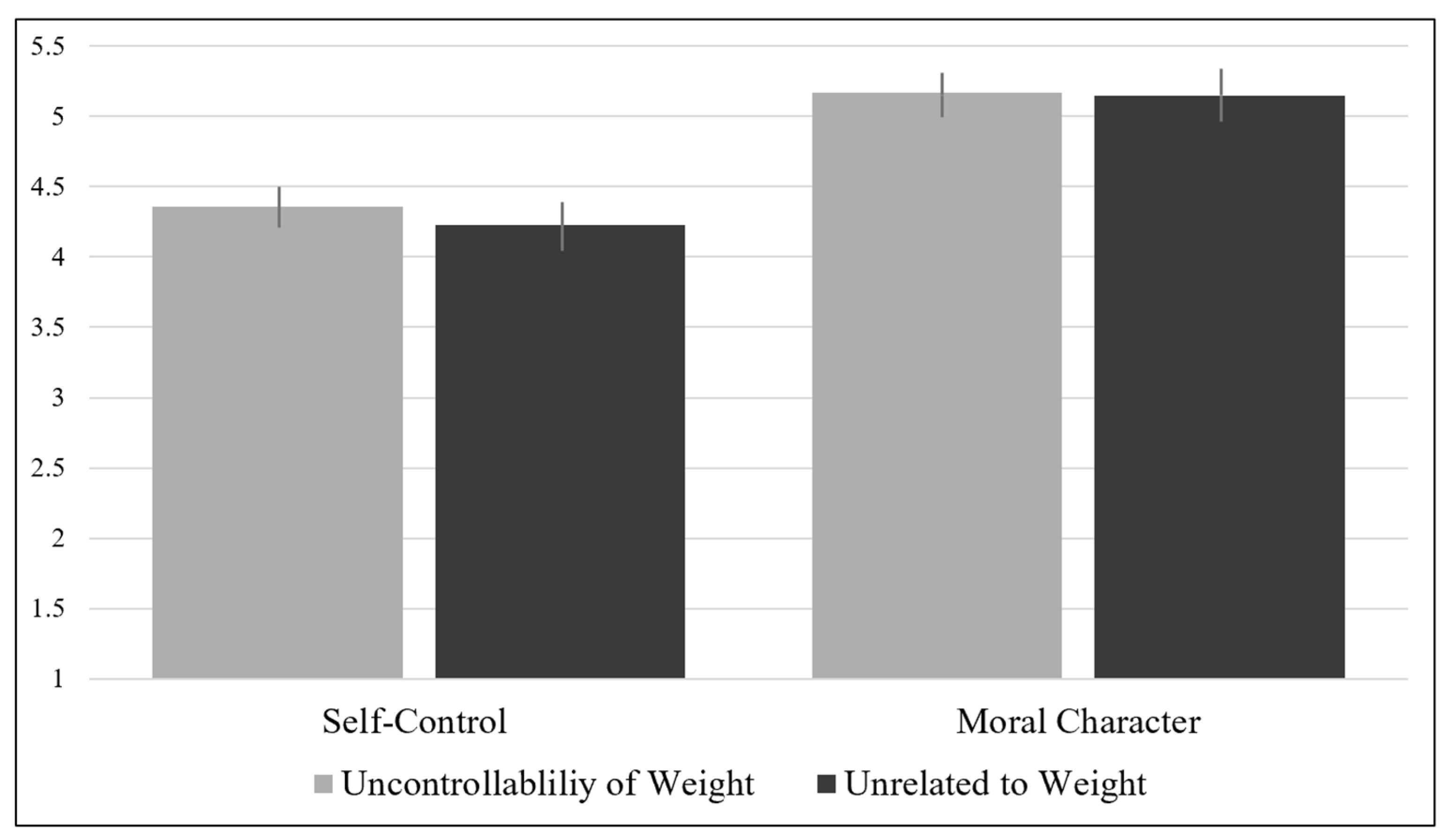

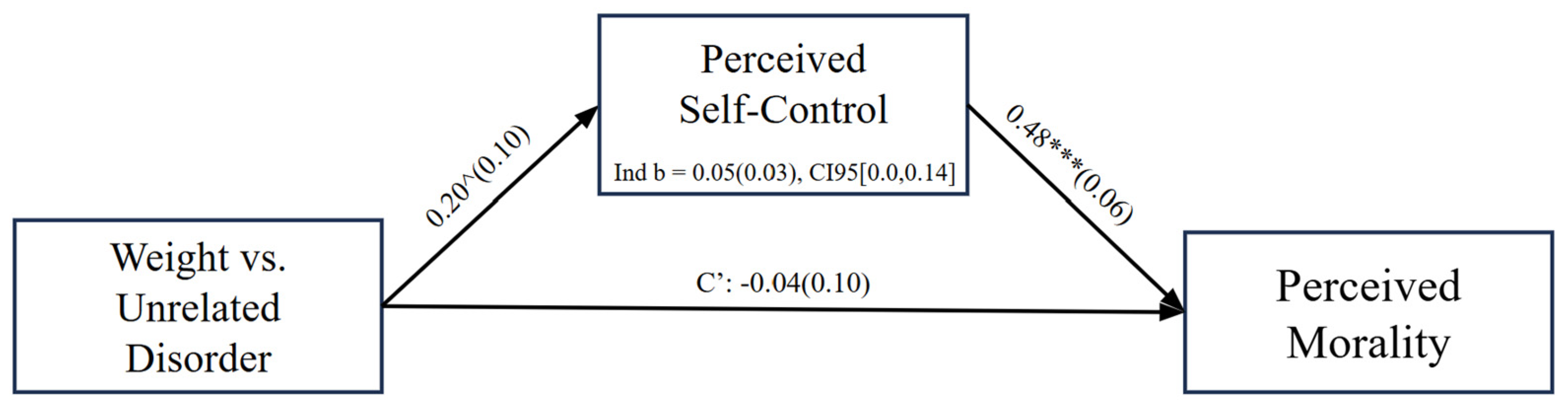

2.3. Results and Discussion

| Self-Control | Moral Character | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncontrollable Weight | Unrelated to Weight | Uncontrollable Weight | Unrelated to Weight | |

| Mean | 4.36 | 4.23 | 5.17 | 5.15 |

| SD | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.78 | 0.92 |

3. Study 2

3.1. Method

3.2. Procedure and Materials

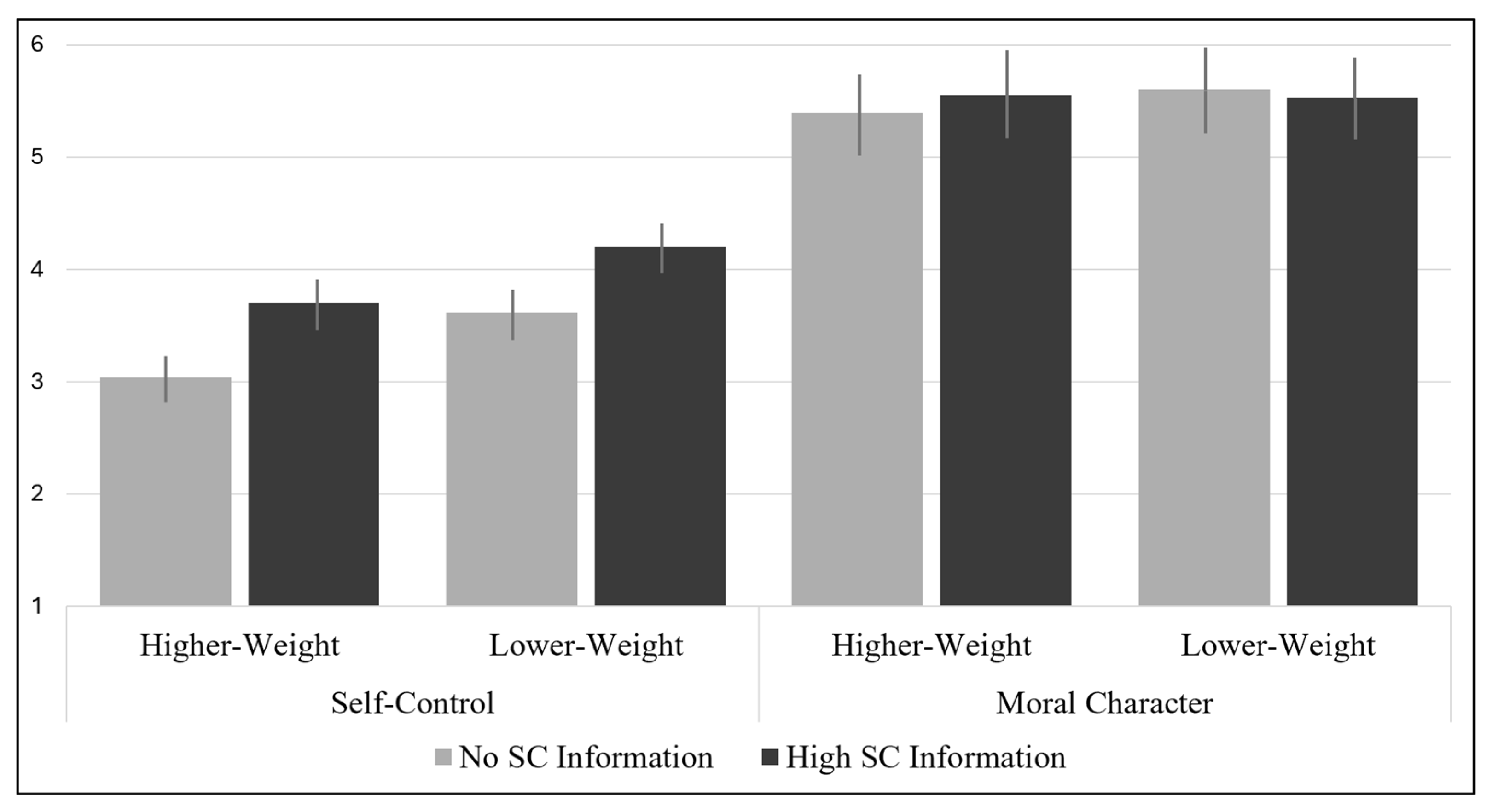

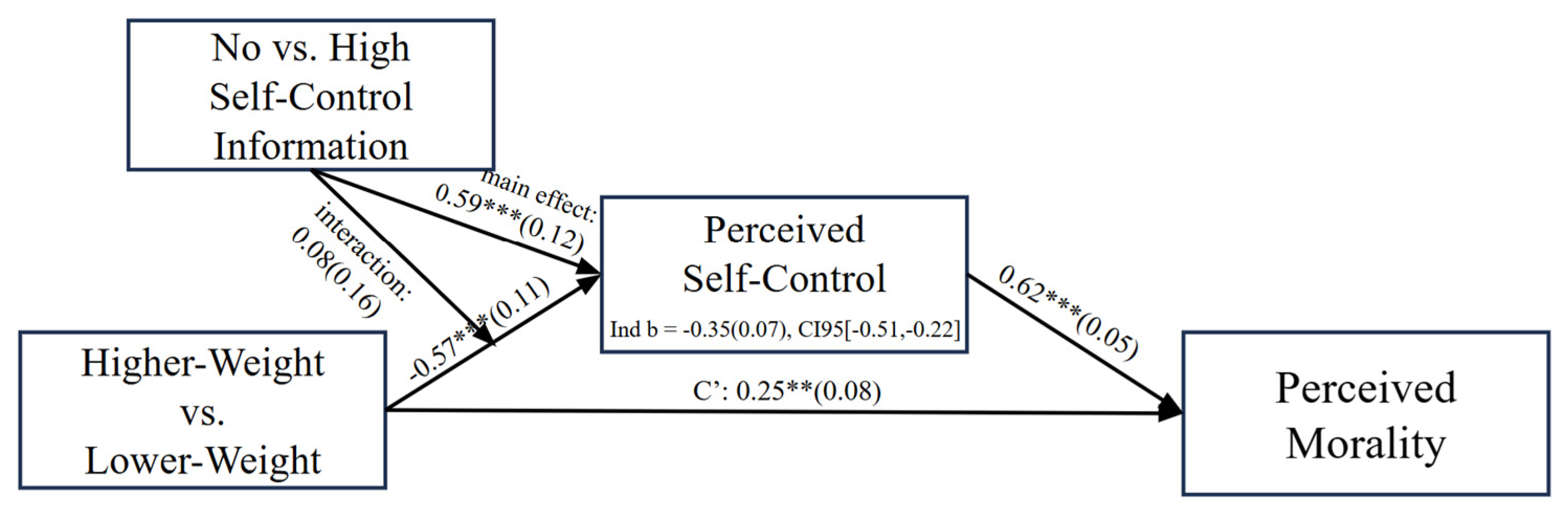

3.3. Results

4. General Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Targets Varying in Weight

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Study 1 Manipulations

Appendix B.1.1. Disorder Manipulation

Appendix B.1.2. Metabolic Disorder—Uncontrollable Weight Condition

Appendix B.1.3. Melanin Disorder—Unrelated to Weight Condition

Appendix C

Self-Control Perceptions

- This person is good at resisting temptation.

- This person has a hard time breaking bad habits.

- This person is lazy.

- This person says inappropriate things.

- This person does certain things that are bad for them, if they are fun.

- This person refuses things that are bad for them.

- This person wishes s/he had more self-discipline.

- People would say that this person has iron self-discipline.

- Pleasure and fun sometimes keep this person from getting work done.

- This person has trouble concentrating.

- This person is able to work efficiently toward long-term goals.

- Sometimes this person can’t stop themselves from doing something, even if they know it is wrong.

- This person often acts without thinking through all the alternatives.

Appendix D

Moral Character Perceptions

- This person is basically honest. *

- This person is trustworthy. *

- This person is basically good and kind. *

- This person is trusting of others. *

- I would trust this person. *

- This person would respond in kind when they are trusted by others. *

- This person is moral.

- This is a good person.

- This person is caring.

- This person is compassionate.

- This person is fair.

- This person is generous.

- This person is helpful.

- This person is hardworking.

- This person is honest.

- This person is kind.

- This person is just.

- This person is brave.

- This person is decent.

- This person is of good quality.

- This person is honorable.

- This person is worthy of respect.

- This person does not have morals. (R)

- This person is immoral. (R, Study 2)

- This person is appalling. (R, Study 2)

- This person is malicious. (R, Study 2)

- This person is worthless. (R, Study 2)

Appendix E

Distractor Items

- This person is friendly.

- This person is creative.

- This person is mysterious.

- This person is artistic.

- This person is outdoorsy.

- This person is open to new experiences.

- This person is extroverted.

- This person is fashionable.

- This person is religious.

- This person is neurotic.

- This person is conscientious.

- This person is agreeable.

- This person is atheist.

- This person is likable.

- This person is liberal.

Appendix F

Memory Checks

- What was your partner’s name?

- How would you describe your partner’s height?

- Short

- Average

- Tall

- I don’t know *

- How would you describe your partner’s weight?

- Underweight

- Average

- Overweight

- I don’t know *

- What else can you remember about your partner? What did he or she look like? What did he or she do for a living? What did he or she do in his or her spare time? Where was he or she from? [Open Response]

Appendix G

Appendix G.1. Study 1 Control Analyses

| Predictor | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficient | t | p | 95% C.I. for B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E. | Beta | Lower | Upper | |||

| Disorder Condition | 0.186 | 0.103 | 0.105 | 1.798 | 0.074 | −0.018 | 0.389 |

| Disgust | −0.287 | 0.042 | −0.433 | −6.816 | <0.001 | −0.370 | −0.204 |

| Attractiveness | 0.125 | 0.037 | 0.218 | 3.417 | <0.001 | 0.053 | 0.198 |

| BMI (Participant) | −0.010 | 0.011 | −0.075 | −0.840 | 0.402 | −0.032 | 0.013 |

| Subjective Weight (Participant) | 0.040 | 0.078 | 0.047 | 0.518 | 0.605 | −0.113 | 0.193 |

| Predictor | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p | 95% C.I. for B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E. | Beta | Lower | Upper | |||

| Disorder Condition | 0.076 | 0.099 | 0.045 | 0.770 | 0.442 | −0.119 | 0.271 |

| Disgust | −0.289 | 0.040 | −0.455 | −7.182 | <0.001 | −0.369 | −0.210 |

| Attractiveness | 0.122 | 0.035 | 0.221 | 3.475 | <0.001 | 0.053 | 0.191 |

| BMI (Participant) | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.032 | 0.358 | 0.721 | −0.018 | 0.025 |

| Subjective Weight (Participant) | −0.087 | 0.074 | −0.105 | −1.168 | 0.244 | −0.233 | 0.060 |

Appendix G.2. Study 2 Control Analyses

| Predictor | F | p |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 198.803 | <0.001 |

| Weight Condition | 2.758 | 0.098 |

| Self-Control Information Condition | 0.338 | 0.562 |

| Weight Condition × Self-Control Info Condition | 1.100 | 0.295 |

Appendix H

Appendix H.1. Study 2 Manipulations

Appendix H.1.1. Self-Control Manipulation

High Self-Control Information

No Self-Control Information

Appendix I

Study 2 Bayesian Analyses

| Parameter | Posterior | 95% Credible Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Mean | Variance | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| Hi SC Information × Lower Weight | 4.202 | 4.202 | 0.007 | 4.044 | 4.361 |

| No SC Information × Lower Weight | 3.615 | 3.615 | 0.007 | 3.453 | 3.778 |

| Hi SC Information × Higher Weight | 3.703 | 3.703 | 0.007 | 3.545 | 3.862 |

| Hi SC Information × Higher Weight | 3.042 | 3.042 | 0.006 | 2.886 | 3.197 |

| Parameter | Posterior | 95% Credible Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Mean | Variance | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| Hi SC Information × Lower Weight | 5.525 | 5.525 | 0.009 | 5.341 | 5.709 |

| No SC Information × Lower Weight | 5.603 | 5.603 | 0.009 | 5.414 | 5.791 |

| Hi SC Information × Higher Weight | 5.547 | 5.547 | 0.009 | 5.364 | 5.731 |

| Hi SC Information × Higher Weight | 5.393 | 5.393 | 0.008 | 5.212 | 5.573 |

References

- Allport, F. H. (1954). The structuring of events: Outline of a general theory with applications to psychology. Psychological Review, 61(5), 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaver, K. M., DeLisi, M., Mears, D. P., & Stewart, E. (2009). Low self-control and contact with the criminal justice system in a nationally representative sample of males. Justice Quarterly, 26, 695–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaine, B. E., DiBlasi, D. M., & Connor, J. M. (2002). The effect of weight loss on perceptions of weight controllability: Implications for prejudice against overweight people. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 7(1), 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder, S., & Lundgren, L. (2019). Roots of group threat: Anti-prejudice motivations and implicit bias in perceptions of immigrants as threats. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 42(12), 1971–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochu, P. M. (2020). Testing the effectiveness of a weight bias educational intervention among clinical psychology trainees. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 51(5), 12653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochu, P. M., & Esses, V. M. (2011). What’s in a name? The effects of the labels “fat” versus “overweight” on weight Bias1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(8), 1981–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttlar, B., Pauer, S., Scherrer, V., & Hofmann, W. (2024). Attitude-based self-regulation: An experience sampling study on the role of attitudes in the experience and resolution of self-control conflicts in the context of vegetarians. Motivation Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Vazquez, R. M., & Gonzalez, E. (2020). Obesity and hiring discrimination. Economics and Human Biology, 37, 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, T. E. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2019). Patterns of implicit and explicit attitudes: I. Long-term change and stability from 2007 to 2016. Psychological Science, 30(2), 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, T. E. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2022). Patterns of implicit and explicit attitudes: IV. Change and stability from 2007 to 2020. Psychological Science, 33(9), 1347–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, C. S. (1994). Prejudice against fat people: Ideology and self-interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandall, C. S., D’Anello, S., Sakalli, N., Lazarus, E., Nejtardt, G. W., & Feather, N. T. (2001). An attribution-value model of prejudice: Anti-fat attitudes in six nations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(1), 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, D. T., Lensvelt-Mulders, G., Finkenauer, C., Stok, F. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2012). Taking stock of self-control: A meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(1), 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diedrichs, P. C., & Barlow, F. K. (2011). How to lose weight bias fast! Evaluating a brief anti-weight bias intervention. British Journal of Health Psychology, 16(4), 846–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. H., Ashmore, R. D., Makhijani, M. G., & Longo, L. C. (1991). What is beautiful is good, but…: A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engell, A. D., Haxby, J. V., & Todorov, A. (2007). Implicit trustworthiness decisions: Automatic coding of face properties in the human amygdala. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(9), 1508–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikkan, J. L., & Rothblum, E. D. (2012). Is fat a feminist issue? Exploring the gendered nature of weight bias. Sex Roles, 66, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitouchi, L., André, J. B., & Baumard, N. (2022). Moral disciplining: The cognitive and evolutionary foundations of puritanical morality. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 46, e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, S. W., Hudson, J., & Lavallee, D. (2013). Counter-conditioning as an intervention to modify anti-fat attitudes. Health Psychology Research, 1(2), e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gai, P. J., & Bhattacharjee, A. (2022). Willpower as moral ability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 159(8), 1999–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebl, M. R., Ruggs, E. N., Singletary, S. L., & Beal, D. J. (2008). Perceptions of obesity across the lifespan. Obesity, 16(S2), S46–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunger, J. M., Dodd, D. R., & Smith, A. R. (2020). Weight discrimination, anticipated weight stigma, and disordered eating. Eating Behaviors, 37, 101383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, J. M., Major, B., Blodorn, A., & Miller, C. T. (2015). Weighed down by stigma: How weight-based social identity threat contributes to weight gain and poor health. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(6), 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., & Cable, D. M. (2011). When it comes to pay, do the thin win? The effect of weight on pay for men and women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksinan, A. J., Almenara, C. A., & Vaculík, M. (2017). The effect of belief in weight controllability on anti-fat attitudes: An experimental manipulation. European Review of Applied Psychology, 67(3), 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C. K., & Le Forestier, J. M. (2025). A comparative investigation of interventions to reduce anti-fat prejudice across five implicit measures. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latner, J. D., O’Brien, K. S., Durso, L. E., Brinkman, L. A., & MacDonald, T. (2008). Weighing obesity stigma: The relative strength of different forms of bias. International Journal of Obesity, 32(7), 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latner, J. D., Simmonds, M., Rosewall, J. K., & Stunkard, A. J. (2007). Assessment of obesity stigmatization in children and adolescents: Modernizing a standard measure. Obesity, 15(12), 3078–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, C. W., Carraro, L., Garcia, R. L., & Kang, J. J. (2017). Morality stereotyping as a basis of women’s in-group favoritism: An implicit approach. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 20(2), 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahey, T. M., Xu, X., Unick, J. L., & Wing, R. R. (2014). A preliminary investigation of the role of self-control in behavioral weight loss treatment. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, 8(2), e149–e153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttrell, A., Petty, R. E., Briñol, P., & Wagner, B. C. (2016). Making it moral: Merely labeling an attitude as moral increases its strength. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 65, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranges, H. M., Timbs, C. L., Ainsworth, S. E., & March, D. S. (2025). Moralization of weight based on concerns about self-control and cooperation. Unpublished Manuscript.

- March, D. S., Gaertner, L., & Olson, M. A. (2021). Danger or dislike: Distinguishing threat from negative valence as sources of automatic anti-Black bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(5), 984–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, M., Sriram, N., Schnabel, K., Maliszewski, N., Devos, T., Ekehammar, B., Wiers, R., HuaJian, C., Somogyi, M., Shiomura, K., Schnall, S., Neto, F., Bar-Anan, Y., Vianello, M., Ayala, A., Dorantes, G., Park, J., Kesebir, S., Pereira, A., … Nosek, B. A. (2013). Overweight people have low levels of implicit weight bias, but overweight nations have high levels of implicit weight bias. PLoS ONE, 8(12), Article e83543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S. B., Rhea, D. J., Greenleaf, C. A., Judd, D. E., & Chambliss, H. O. (2011). Weight control beliefs, body shape attitudes, and physical activity among adolescents. Journal of School Health, 81(5), 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, T. B., Mozdzierz, P., Wang, S., & Smith, K. E. (2021). Discrimination and eating disorder psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy, 52(2), 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matharu, K., Shapiro, J. F., Hammer, R. R., Kravitz, R. L., Wilson, M. D., & Fitzgerald, F. T. (2014). Reducing obesity prejudice in medical education. Education for Health, 27(3), 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, A. C. (2013). The interpersonal costs of indulgence. Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, C. H., Oliver, T. L., Randolph, J., & Dowdell, E. B. (2022). Interventions for reducing weight bias in healthcare providers: An interprofessional systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Obesity, 12(6), e12545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, F., Inam, A., & Akhtar, Z. (2020). Accuracy of consensual stereotypes in moral foundations: A gender analysis. PLoS ONE, 15(3), e0229926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K. S., Latner, J. D., Ebneter, D., & Hunter, J. A. (2013). Obesity discrimination: The role of physical appearance, personal ideology, and anti-fat prejudice. International Journal of Obesity, 37(3), 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K. S., Puhl, R. M., Latner, J. D., Mir, A. S., & Hunter, J. A. (2010). Reducing anti-fat prejudice in preservice health students: A randomized trial. Obesity, 18(11), 2138–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, M. A., & Fazio, R. H. (2008). Implicit and explicit measures of attitudes: The perspective of the MODE model. In Attitudes (pp. 39–84). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paolini, S., Gibbs, M., Sales, B., Anderson, D., & McIntyre, K. (2024). Negativity bias in intergroup contact: Meta-analytical evidence that bad is stronger than good, especially when people have the opportunity and motivation to opt out of contact. Psychological Bulletin, 150(8), 921–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.-H., Jeong, Y.-W., Park, H.-K., Park, S.-G., & Kim, H.-Y. (2024). Mediating effect of self-control on the relationship between obesity-related stress and weight control behavior among female college students with overweight and obesity. Healthcare, 12(5), 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, H., & Haddock, G. (2007). Anti-fat prejudice among children: The “mere proximity” effect in 5–10 year olds. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(4), 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policardo, G. R., Karataş, S., & Prati, F. (2025). A blind spot in intergroup contact: A systematic review on predictors and outcomes of inter-minority contact experiences. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 104, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R. M., & Brownell, K. D. (2013). Bias, discrimination and obesity. Health and Human Rights in a Changing World, 9, 581–606. [Google Scholar]

- Puhl, R. M., & Heuer, C. A. (2009). The stigma of obesity: A review and update. Obesity, 17(5), 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R. M., Latner, J. D., O’Brien, K., Luedicke, J., Danielsdottir, S., & Forhan, M. (2015). A multinational examination of weight bias: Predictors of anti-fat attitudes across four countries. International Journal of Obesity, 39(7), 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R. M., Luedicke, J., & Heuer, C. (2011). Weight-based victimization toward overweight adolescents: Observations and reactions of peers. Journal of School Health, 81(11), 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringel, M. M., & Ditto, P. H. (2019). The moralization of obesity. Social Science & Medicine, 237, 112399. [Google Scholar]

- Rouder, J. N., Speckman, P. L., Sun, D., Morey, R. D., & Iverson, G. (2009). Bayesian t tests for accepting and rejecting the null hypothesis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Rukavina, P. B., Li, W., Shen, B., & Sun, H. (2010). A service learning based project to change implicit and explicit bias toward obese individuals in kinesiology pre-professionals. Obesity Facts, 3(2), 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, K. M., Deane, F. P., Tapsell, L., & Kelly, P. J. (2018). Gender differences in the relationship of weight-based stigmatisation with motivation to exercise and physical activity in overweight individuals. Health Psychology Open, 5(1), 2055102918759691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M. B., Vartanian, L. R., Nosek, B. A., & Brownell, K. D. (2006). The influence of one’s own body weight on implicit and explicit anti-fat bias. Obesity, 14(3), 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, S. J., Zanna, M. P., & Fong, G. T. (2005). Establishing a causal chain: Why experiments are often more effective than mediational analyses in examining psychological processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielmann, N., Gomez, P., & Minton, E. (2024). The role of the ugly= bad stereotype in the rejection of misshapen produce. Journal of Business Ethics, 190(2), 413–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S. J. F., & Ogden, J. (2021). The role of social exposure in predicting weight bias and weight bias internalisation: An international study. International Journal of Obesity, 45(6), 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y., & Terracciano, A. (2015). Weight discrimination and risk of mortality. Psychological Science, 26(11), 1803–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, J. A., Hanlon, S., El-Redy, L., Puhl, R. M., & Glazebrook, C. (2013). Weight bias among UK trainee dietitians, doctors, nurses and nutritionists. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics: The Official Journal of the British Dietetic Association, 26(4), 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanneberger, A., & Ciupitu-Plath, C. (2018). Nurses’ weight bias in caring for obese patients: Do weight controllability beliefs influence the provision of care to obese patients? Clinical Nursing Research, 27(4), 414–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teachman, B. A., & Brownell, K. D. (2001). Implicit anti-fat bias among health professionals: Is anyone immune? International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 25(10), 1525–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teachman, B. A., Gapinski, K. D., Brownell, K. D., Rawlins, M., & Jeyaram, S. (2003). Demonstrations of implicit anti-fat bias: The impact of providing causal information and evoking empathy. Health Psychology, 22(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, L. R. (2010). Disgust and perceived control in attitudes toward obese people. International Journal of Obesity, 34(8), 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, L. R., Pinkus, R. T., & Smyth, J. M. (2018). Experiences of weight stigma in everyday life: Implications for health motivation. Stigma and Health, 3(2), 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, L. R., Thomas, M. A., & Vanman, E. J. (2013). Disgust, contempt, and anger and the stereotypes of obese people. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 18, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, L. R., Trewartha, T., & Vanman, E. J. (2016). Disgust predicts prejudice and discrimination toward individuals with obesity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 46(6), 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazsonyi, A. T., Mikuška, J., & Kelley, E. L. (2017). It’s time: A meta-analysis on the self-control–deviance link. Journal of Criminal Justice, 48, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, T. J., & DiMaria, C. (2003). Weight halo effects: Individual differences in perceived life success as a function of women’s race and weight. Sex Roles, 48, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, T. J., Loyden, J., Renninger, L., & Tobey, L. (2003). Weight halo effects: Individual differences in personality evaluations as a function of weight? Personality and Individual Differences, 34(2), 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, T., & Yamagishi, M. (1994). Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motivation and Emotion, 182, 129–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Higher Weight | Lower Weight | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No SC Information | High SC Information | No SC Information | High SC Information | |

| Mean | 3.042 | 3.703 | 3.615 | 4.202 |

| SD | 0.558 | 0.794 | 0.729 | 0.748 |

| Higher Weight | Lower Weight | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No SC Information | High SC Information | No SC Information | High SC Information | |

| Mean | 5.393 | 5.547 | 5.603 | 5.525 |

| SD | 0.691 | 0.953 | 0.856 | 0.786 |

| Predictor | F | p |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 13,872.073 | <0.001 |

| Weight Condition | 0.997 | 0.319 |

| Self-Control Information Condition | 0.168 | 0.682 |

| Weight Cond × SC Info Cond | 1.541 | 0.215 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Timbs, C.L.; Maranges, H.M. Does Control-Related Information Attenuate Biased Self-Control and Moral Perceptions Based on Weight? Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070970

Timbs CL, Maranges HM. Does Control-Related Information Attenuate Biased Self-Control and Moral Perceptions Based on Weight? Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):970. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070970

Chicago/Turabian StyleTimbs, Casey L., and Heather M. Maranges. 2025. "Does Control-Related Information Attenuate Biased Self-Control and Moral Perceptions Based on Weight?" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070970

APA StyleTimbs, C. L., & Maranges, H. M. (2025). Does Control-Related Information Attenuate Biased Self-Control and Moral Perceptions Based on Weight? Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070970