Abstract

A clear understanding of one’s identity is essential for adolescents to lead a meaningful and purposeful life. We investigated the relationship between self-concept clarity and meaning in life among 2288 adolescents through a cross-sectional survey, using both variable-centered and person-centered approaches. The results revealed a significant positive correlation between self-concept clarity and meaning in life among Chinese adolescents, as well as its dimensions. Three distinct profiles of self-concept clarity were identified among adolescents: high, medium, and low. The profile with high self-concept clarity had the highest meaning in life, followed by the moderate self-concept clarity profile, while the low self-concept clarity group had the lowest meaning in life. The findings underscore the enduring impact of self-concept clarity on adolescents’ meaning in life, affirming its central function within the self-concept structure in shaping meaning in life.

1. Introduction

Meaning in life is an important predictor of physical and mental health (Czekierda et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2019; Roepke et al., 2014; Steger, 2017; Zhao et al., 2017). Viktor Frankl, the founder of logotherapy, asserts that numerous psychological distress and mental health problems frequently stem from a fundamental absence of meaning in life (Steger et al., 2008). The absence of meaning in life might result in feelings of emptiness, boredom, depression (H. Park & Jeong, 2016), post-traumatic stress disorder (Fischer et al., 2020), and even behaviors such as self-harm and suicide (Costanza et al., 2019; Ilagan, 2023).

More researchers are recognizing the positive influence of meaning in life (Steger et al., 2008). Individuals with a high level of meaning in life tend to experience greater well-being (Krok, 2018), stronger psychological resilience (Lin, 2021), and better academic performance (Makola, 2014; Mason, 2017). Meanwhile, meaning in life also serves a protective function, effectively alleviating depression and anxiety in adolescents (Korkmaz & Güloğlu, 2021; Tsibidaki, 2021), and acting as an important buffer against everyday stress (J. Park & Baumeister, 2017). Following traumatic events, individuals with high meaning in life typically report greater use of effective coping strategies and faster recovery from trauma (Jim et al., 2006). Therefore, guiding adolescents to develop a proper understanding of life’s value and encouraging them to pursue its meaning carries significant theoretical and practical implications.

For adolescents, having a clear understanding of who they are is essential for leading a meaningful and purposeful life (Thomas et al., 2022). Self-concept clarity plays a crucial role in regulating cognition, emotion, and behavior within self-involving contexts. Therefore, its influence on adolescents’ meaning in life should not be overlooked, as it serves as a powerful source of meaning in life (Boucher et al., 2016).

Most existing research on the association between self-concept clarity and meaning in life has been grounded in the two-dimensional conceptualization of meaning in life. Measurement tools have mostly focused on the “presence of meaning” and “search for meaning” (Steger et al., 2006). Thus, although prior research has demonstrated a positive link between self-concept clarity and meaning in life, the relationship has been assessed largely through individuals’ intuitive perceptions of meaning (Hicks & King, 2009), potentially overlooking the deeper structure of meaning in life. In recent years, researchers have found that the three-dimensional concept of meaning in life goes beyond merely focusing on the surface of “meaning” and more deeply reflects the intrinsic characteristics of meaning in life (Costin & Vignoles, 2020; George & Park, 2017; King & Hicks, 2021; Martela & Steger, 2016). With the adoption of the three-dimensional framework, meaning in life is now understood to comprise three key dimensions: coherence, purpose, and significance (George & Park, 2017; Martela & Steger, 2016). Coherence refers to individuals’ perceptions of the consistency of their lives and the extent to which they feel understood. Purpose refers to the extent to which individuals perceive their lives as being guided and motivated by meaningful goals. Significance refers to the extent to which individuals feel that their existence holds value. This expanded perspective provides an opportunity to explore how self-concept clarity might relate differently to each dimension, thus enriching our understanding of the effect through which self-concept clarity contributes to meaning in life.

Self-concept clarity might influence individuals’ perception of the coherence of meaning in their life experiences. Self-Verification Theory suggests that individuals are motivated to seek, accept, and retain information that aligns with their existing self-concept, while discounting or resisting information that is inconsistent with it (Swann, 1997). Therefore, self-concept clarity is essential for how individuals experience and perceive the world. Self-concept clarity facilitates the establishment and maintenance of a stable identity (Gregg & Sedikides, 2018; Pilarska, 2016; Schwartz et al., 2011), which in turn supports individuals in constructing meaningful life narratives through self-storytelling, integrating life events into a coherent whole. Self-concept clarity helps individuals expand their self in relational domains, providing additional sources of relational support for coherent life experiences (Emery et al., 2015). This, in turn, promotes healthier and more stable social support, thereby introducing an interpersonal dimension to the coherence of life. Additionally, individuals with high self-concept clarity are more adaptable and can flexibly respond to changes in life (Miyagawa, 2022), allowing them to adjust their behaviors and goals to fit new situations, thereby maintaining coherence. In contrast, uncertainty about one’s identity might have the opposite effect, ultimately undermining the perception of coherence (George & Park, 2016). For example, low self-concept clarity directly undermines an individual’s self-continuity and can also impair self-continuity by reducing the role of self-reflection and self-narrative in autobiographical memory (Jiang et al., 2023), ultimately leading to a decline in meaning in life (Chu & Lowery, 2024). Therefore, self-concept clarity might influence the perceived coherence of life.

Self-concept clarity might influence individuals’ perception of pursuing valuable goals and establishing clear directions in life. According to the model proposed by Light (2017) on the role of self-concept clarity in goal pursuit, self-concept clarity might play a role in the pre-decision, post-decision, pre-action, and action stages of goal pursuit. In the pre-decision stage, high self-concept clarity helps individuals set clear and achievable goals. Low self-concept clarity might lead individuals to struggle with determining what they truly want, thereby reducing goal clarity. Previous research has shown that individuals with high self-concept clarity perform better in social decision-making, while those with lower self-concept clarity tend to show indecisiveness, leading to poorer social decisions (Uğurlar & Wulff, 2022). In the post-decision and pre-action stages, individuals with high self-concept clarity have a clearer understanding of their strengths and weaknesses. They consider their abilities and limitations and seek accurate information about themselves to support goal achievement. Adolescents with high self-concept clarity are more optimistic, have a longer-term perspective on the future (Morawiak et al., 2018; Steger et al., 2009), are more willing to invest effort in learning, exhibit greater persistence (Gupta & Bakker, 2020), and are more likely to persist in pursuing their goals while resisting temptations (Jiang et al., 2023). In the action stage, individuals primarily focus on taking concrete steps toward their goals. Individuals with high self-concept clarity are more likely to adopt proactive coping strategies in the process of goal achievement (Smith et al., 1996) and exhibit greater persistence (Fite et al., 2017; Wong & Vallacher, 2018). At the same time, individuals with high self-concept clarity are better able to focus their attention and determination while pursuing goals, making them less susceptible to external distractions (Jiang et al., 2023), which increases their goal achievement and purpose in life. In contrast, individuals with low self-concept clarity might adopt more passive coping strategies (Smith et al., 1996), hindering goal attainment and leading to a decrease in their sense of purpose in life. Therefore, self-concept clarity might influence the development and maintenance of an individual’s sense of purpose.

Self-concept clarity might influence individuals’ perception of their self-worth and significance. Firstly, self-concept clarity is associated with a more confident, internally consistent, and accessible self-view, which makes individuals less sensitive to external feedback, particularly negative feedback (Guerrettaz et al., 2014). Lower sensitivity to negative feedback could help individuals cultivate and maintain stronger significance. Research has also shown that individuals with higher self-concept clarity have a stronger association with self-worth (Ferris et al., 2009; Koriat, 2012; B. Zhang & Lin, 2023). Secondly, self-concept clarity could influence individuals’ perceived significance by affecting their true self. Individuals with high self-concept clarity are more likely to experience their true self (Boucher, 2011, 2021; Kraus et al., 2011). The true self reflects alignment between an individual’s behavior and their unique sources of significance, thereby increasing the perceived importance (Lutz et al., 2023). Moreover, self-esteem, a psychological construct closely related to self-concept clarity (Weber et al., 2023), is strongly associated with perceived significance. High self-esteem helps individuals develop positive self-cognitions, viewing themselves as valuable and meaningful. In conclusion, self-concept clarity might influence individuals’ perceived importance.

Moreover, in previous studies examining the relationship between self-concept clarity and meaning in life, most have assessed self-concept clarity based on the total or average scores. However, this method often overlooks the heterogeneity within groups (Xiang, 2022), which might lead to inaccurate categorization. The person-context interaction theory proposes that complex environments may lead to diversity as a fundamental feature of human development. Individuals with different characteristics tend to cluster together based on similar combinations of psychological and behavioral traits, thus forming relatively stable “types”(Magnusson & Stattin, 1998). In line with the theory, individual differences in self-concept clarity may also demonstrate distinct patterns, suggesting the presence of diverse subgroups. Therefore, to explore heterogeneity in participants’ self-concept clarity, latent profile analysis was used to classify individuals into distinct groups based on their response patterns (Q. Li et al., 2022; Xiang, 2022). Studies have demonstrated that adolescents’ self-concept clarity existed in three profiles: high, medium, and low.

Previous research has shown that indicated that self-concept clarity varies by age and gender; but the results are inconsistent (Crocetti et al., 2016; Lodi-Smith et al., 2017; Xiang et al., 2023). The findings on age and gender differences in self-concept clarity vary, possibly due to cultural differences, limited sample representativeness, or small sample sizes. In addition, only one study has indicated that age and gender influence the profiles of self-concept clarity (Xiang et al., 2021). Therefore, the study aims to provide new evidence supporting the impact of age and gender on the profiles of self-concept clarity.

Meanwhile, individuals with different profiles of self-concept clarity experience differential levels of subjective well-being subjective well-being (Xiang, 2022). However, a compelling and underexplored question is whether individuals characterized by different profiles of self-concept clarity experience distinct levels of meaning in life.

Therefore, within the framework of the three-dimensional conceptualization of meaning in life, the study adopts both variable-centered and person-centered approaches to examine the relationship between self-concept clarity and adolescents’ meaning in life. The former explores the overall association between the two constructs, while the latter investigates how different profiles of self-concept clarity relate to adolescents’ meaning in life.

The specific hypotheses are as follows:

H1.

Self-concept clarity is positively associated with adolescents’ meaning in life and its various dimensions.

H2.

Age and gender are significantly associated with the profiles of self-concept clarity.

H3.

Self-concept clarity exists in different profiles, and adolescents’ meaning in life varies across these profiles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A cluster sampling strategy was adopted, and data were gathered from three middle schools and one university across three different cities in Henan Province, comprising a total of 2288 adolescents. Among them, 540 were junior middle school students, with the average age of 13.73 years (SD = 0.77). Of the junior middle school students, 282 were male, 258 were female, and 512 were non-only children (2 participants did not respond). In terms of residential areas, 130 participants were from urban areas, 186 were from towns, and 221 were from rural areas, with 3 participants not providing this information. Among them, 634 were senior high school students, with the average age of 16.61 years (SD = 0.71). Among the senior high school students, 234 were male, 400 were female, and 609 were non-only children (4 participants did not provide a response). Regarding residential areas, 77 participants were from urban areas, 130 from towns, and 422 from rural areas, with 5 participants not reporting this information. The university sample consisted of 1114 students, with a mean age of 18.47 years (SD = 0.89). Of these, 466 were male, 648 were female, and 983 were non-only children. In terms of residential areas, 248 participants were from urban areas, 234 from towns, and 632 from rural areas.

2.2. Measures

Self-Concept Clarity: the scale revised by Niu et al. (2016), based on the original measure developed by Campbell et al. (1996), was used. It consists of 12 items (sample item: if I were to describe my personality, perhaps my description would be different every day) with all items being reverse-scored except for items 6 and 11. The scale used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-concept clarity. The scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity in Chinese samples (Niu et al., 2016; D. Zhang, 2018). The structural validity in the study was satisfactory, χ2(49) = 317.27, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.03, Cronbach’s α was 0.82.

Meaning in life: we used the Multidimensional Meaning in Life Scale (George & Park, 2017), translated by Zhou et al. (2018). The scale consists of 15 items, including three dimensions: coherence (sample item: I can make sense of the things that happen in my life), purpose (sample item: I have aims in my life that are worth striving for), and significance (sample item: I am certain that my life is of importance), with 5 items for each dimension. It uses a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher meaning in life. The results showed that the original scale had good structural validity, χ2(73) = 618.46, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.03. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the scale and its dimensions were 0.94, 0.84, 0.90, and 0.85.

2.3. Research Procedure

In compliance with the principle of informed consent, and after obtaining approval from both the school and the students, a cluster sampling method was employed for the survey. Given the practical conditions of junior and senior high school students, paper-based questionnaires were used. Class teachers were responsible for administering the survey and distributing and collecting the questionnaires during class. To optimize the process, college students completed the survey via Wenjuanxing, with the class counselors and psychology representatives jointly overseeing the administration, distributing survey links. Prior to data collection, the researcher provided a standardized reading of the informed consent form to all participants, thoroughly explaining the purpose of the study, clarifying its scientific basis, and assuring that all responses would remain strictly confidential and be used exclusively for academic research. To ensure the authenticity of responses, participants were informed that there were no correct or incorrect answers and were encouraged to answer honestly based on their personal experiences.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and group comparison tests were conducted using SPSS 25.0, while latent profile analysis was performed using Mplus 8.0. The model fit indices were primarily evaluated based on three categories. The first category includes information criteria, such as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the sample size adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (aBIC), with smaller values indicating better fit. The second category includes Entropy, which represents the accuracy of classification. The range of values is from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating greater accuracy. A value below 0.6 suggests that more than 20% of individuals are misclassified, while a value above 0.8 indicates that the classification accuracy exceeds 90%. Specifically, a value greater than 0.8 indicates high classification accuracy (Jung & Wickrama, 2008). The third category includes likelihood ratio indices, such as the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (VLMR-LRT), which indicates whether the model with K categories fits better than the model with K-1 categories. In addition to relying on the aforementioned model fit indices to determine the optimal number of categories, prior research and theoretical considerations should also be taken into account to finalize the most appropriate classification solution (Nylund et al., 2007).

3. Results

3.1. The Development of Adolescents’ Self-Concept Clarity and Meaning in Life

The development of self-concept clarity and meaning in life in adolescents is shown in Table 1. First, self-concept clarity (F(2, 2282) = 51.51, p < 0.001, = 0.04), meaning in life (F(2, 2282) = 53.78, p < 0.001, = 0.05), coherence (F(2, 2282) = 55.66, p < 0.001, = 0.05), purpose (F(2, 2282) = 57.49, p < 0.001, = 0.05), and significance (F(2, 2282) = 31.73, p < 0.001, = 0.03) were different among different age groups. Specifically, junior middle school students and senior high school students have lower self-concept clarity compared to college students, but there was no significant difference between junior middle and senior high school students. In terms of overall meaning in life, as well as the dimensions of coherence and purpose, senior high school students scored lower than junior middle school students, who in turn scored lower than college students. Regarding the dimension of significance, college students reported higher levels than both junior middle school and senior high school students, among whom no significant difference was found. Furthermore, both self-concept clarity and meaning in life showed gender differences. Specifically, male adolescents had significantly higher self-concept clarity than female adolescents (t = 6.02, p < 0.001, d = 0.24). Male adolescents also scored higher than female adolescents on meaning in life (t = 2.77, p < 0.001, d = 0.12), coherence (t = 4.55, p < 0.001, d = 0.19), and purpose (t= 3.02, p < 0.001, d = 0.12); however, no gender differences were found regarding significance (t = 0.22, p > 0.05). Finally, there were no significant differences in self-concept clarity or meaning in life between only children and non-only children (p > 0.05). Additionally, the impact of geographic origin on adolescents’ self-concept clarity and meaning in life was also not significant (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Developmental characteristics of adolescents’ self-concept clarity and meaning in Life.

3.2. Correlation Analysis of Self-Concept Clarity and Meaning in Life in Adolescents

The results of the correlation analysis were presented in Table 2. The higher the self-concept clarity, the higher the meaning in life experienced by adolescents. Specifically, self-concept clarity was moderately positively correlated with meaning in life and with each of the dimensions (r = 0.35–0.49).

Table 2.

Correlations between self-concept clarity and meaning in life.

3.3. Latent Profile Analysis and Characteristics of Self-Concept Clarity in Adolescents

To identify latent subtypes of self-concept clarity, latent profile analysis was conducted on the items of the Self-Concept Clarity Scale. From a person-centered perspective, the study further examined differences in adolescents’ meaning in life across distinct self-concept clarity profiles. The model fit indices for the latent profile analysis of self-concept clarity were shown in Table 3. In the study, latent profile models with two to six profiles were sequentially tested. The results indicated that the entropy for the three-profile model was greater than 0.8 (Clark & Muthén, 2009), and the reductions in AIC, BIC, and aBIC were most pronounced at three profiles, which was the inflection point (Nylund-Gibson et al., 2023). For the three-profile model, the probability of classifying each observation into a latent profile ranged from 0.90 to 0.92, indicating high classification accuracy. Therefore, the three-profile model was determined to be the optimal latent profile model.

Table 3.

Fit indices of latent profile analysis for self-concept clarity.

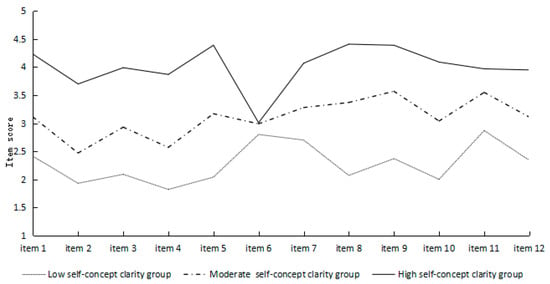

As shown in Figure 1, the first group consisted of 653 adolescents, accounting for 28.54% of the total sample. The group scored lower on the self-concept clarity and was labeled as the low self-concept clarity group. The second group included 1221 adolescents, making up 53.37% of the total sample. The group scored at a moderate level on self-concept clarity and was labeled as the moderate self-concept clarity group. The third group consisted of 414 adolescents, accounting for 18.09% of the total sample. Except for relatively low scores on the sixth item (I rarely feel a conflict between different aspects of my personality), the group scored high on other items, and was labeled as the high self-concept clarity group.

Figure 1.

Latent subgroups of adolescent self-concept clarity.

Using the results of potential profile analysis as the dependent variable, with the low self-concept clarity group as the reference profile, and age stage (with junior middle school students as the reference) and gender (with male adolescents as the reference) as independent variables, a logistic regression was conducted to analyze the Odd Ratio (OR) coefficients, reflecting the probabilities of different age stages and genders on their respective self-concept clarity potential profiles. The results were as follows: compared to junior middle school students, there was a higher proportion of senior high school (OR = 1.35, p < 0.001, 95%CI = [1.05–1.73]) and college students (OR = 1.82, p < 0.001, 95%CI = [1.44–2.41]) in the moderate self-concept clarity group. A similar result was also observed in the high self-concept clarity group where senior high school (OR = 1.20, p < 0.001, 95%CI = [0.81–1.77]) and college students (OR = 3.78, p < 0.001, 95%CI = [2.72–5.27]) also exhibited a higher proportion. The results indicated that compared to junior middle school students, senior high school and college students were more likely to belong to the moderate or high self-concept clarity group. In addition, compared to male adolescents, the proportion of female adolescents in the moderate self-concept clarity group was lower (OR = 0.75, p < 0.05, 95%CI = [0.62–0.92]), and the proportion of female adolescents in the high self-concept clarity group was also lower (OR = 0.47, p < 0.001, 95%CI = [0.37–0.61]). The results indicated that, compared to male adolescents, female adolescents were more likely to belong to the lower self-concept clarity group. All results suggest that age and gender are effective predictive variables for the potential profiles of self-concept clarity.

3.4. The Relationship Between the Profile of Self-Concept Clarity in Adolescents and the Meaning in Life

As shown in Table 4, the results of the group comparison test indicated significant differences in meaning in life among adolescents with the three profiles of self-concept clarity. Through Bonferroni multiple comparisons, it was found that the high self-concept clarity group had the highest meaning in life (5.90 ± 0.93), coherence (5.83 ± 0.98), purpose (5.92 ± 1.12), and significance (5.93 ± 1.03), followed by the moderate self-concept clarity group, while the low self-concept clarity group had the lowest scores.

Table 4.

Differences in meaning in life across profiles of self-concept clarity.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship Between Adolescents’ Self-Concept Clarity and Meaning in Life from Variable-Centered Perspective

The study explored the developmental characteristics and relationships of adolescents’ self-concept clarity and meaning in life from a variable-centered perspective. The results showed that, whether in overall meaning in life or in the dimensions of coherence, purpose, and significance, self-concept clarity was significantly positively correlated with adolescents’ meaning in life. This validated H1 and was consistent with previous research findings on the two-dimensional meaning in life (Błażek & Besta, 2012; Church et al., 2014; Han, 2023; Hasson-Ohayon et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2023; Mai et al., 2023). The study is the first to simultaneously validate that adolescents with higher self-concept clarity have higher meaning in life throughout the entire adolescent stage (including early, middle, and late adolescence), highlighting the stability of the relationship between the two. In addition, there were differences in self-concept clarity among adolescents based on age and gender, which was consistent with previous research (Crocetti et al., 2016; Xiang, 2022; Xiang et al., 2023). The self-concept clarity in junior middle school students is lower than that in college students. In other words, over the course of adolescence, the self-concept clarity in adolescents gradually improves, which to some extent verifies that the self-concept clarity is in a continuous upward trend during this stage (Crocetti et al., 2016; Shin et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2010). The gradual exploration of self-identity and the deepening of self-awareness in adolescents are related. As adolescents mature, they become increasingly capable of clearly identifying and integrating their behaviors across different social roles, thereby facilitating the development of a more coherent and stable self-concept. Additionally, male adolescents have a higher self-concept clarity compared to female adolescents. Previous studies have also shown that female adolescents have lower self-esteem, less stable self-concepts, and lower confidence (Xiang et al., 2021). The reason might be related to societal gender expectations. Males are more likely to learn how to expand themselves, take risks, and achieve goals, and these endeavors might contribute to the development of self-concordance (Elliott, 1988). In contrast, female adolescents tend to place greater emphasis on interpersonal relationships than males do (Joshanloo, 2018), and their self-perception is often influenced by others, which might slow down the development of their self-concept.

Adolescents’ meaning in life also varies by age and gender. In terms of age differences, senior high school students reported the lowest overall meaning in life, coherence, and purpose, with junior middle school students scoring higher than senior high school students but lower than college students. Regarding the perceived importance of meaning, there was no significant difference between junior high and senior high school students, but both groups scored significantly lower than college students. In brief, adolescents in early and middle adolescence show a lower meaning in life compared to those in late adolescence. The study partially confirms that the meaning in life tends to increase dynamically with age during adolescence (Y. Li, 2023), which is generally consistent with the views of Erikson (1968) and Battista and Almond (1973). In other words, adolescents in early and middle adolescence often experience a coexistence of developing identity and frequent psychological challenges, which might make them more susceptible to a relatively lower meaning in life (Erikson, 1968). By contrast, college students in late adolescence typically begin to adopt a more active life orientation. They are more likely to construct a meaning in life through commitment to life goals, the pursuit and attainment of personal aspirations, and deep reflection on life’s significance, thereby enhancing their overall sense of meaning (Battista & Almond, 1973). However, unlike previous studies, the present research did not find a marked increase in the meaning in life during middle adolescence (Wang et al., 2016). Interestingly, the results indicated that adolescents in middle adolescence—particularly those in senior high school—demonstrated the lowest levels of meaning in life compared to their early and late adolescent counterparts. This finding may be closely related to the increasingly severe mental health issues faced by senior high school students in China. A meta-analysis has indicated a temporal deterioration in psychological well-being within this population, with anxiety symptoms being especially pronounced (Yu et al., 2022). The relatively weak association between age and meaning in life observed in this stage might reflect the significant challenges senior high school students face in developing meaning in life. With regard to gender differences, male adolescents reported higher overall levels of meaning in life, coherence, and purpose compared to their female counterparts; however, no significant gender difference was found in the perceived importance of meaning. Although the study employed a different measurement tool from previous research to assess the dimensions of meaning in life, the findings are largely consistent with earlier studies (P. Zhang et al., 2022), particularly in the cognitive dimension (coherence) and the motivational dimension (purpose). During adolescence, males tend to perceive greater connectedness among the self, others, events, and various life elements, and they are more capable of integrating past experiences, present circumstances, and future aspirations into a coherent whole, which aligns with their cognitive characteristics. Furthermore, male adolescents scored higher than female adolescents on the dimension of purpose, which might be closely related to differing societal expectations regarding the life goals of male adolescents and female adolescents.

While variable-centered approaches have provided valuable insights into the relationship between self-concept clarity and adolescents’ meaning in life, such approaches often fall short in capturing intra-individual differences and might overlook important information. Therefore, the following analysis adopts the person-centered perspective to identify the demographic characteristics (e.g., age and gender) of adolescents with different profiles of self-concept clarity, and to explore how these profiles relate to their meaning in life.

4.2. The Relationship Between Adolescents’ Self-Concept Clarity and Meaning in Life from Person-Centered Perspective

The study adopted a person-centered approach to explore the developmental characteristics and interrelations between self-concept clarity and meaning in life among adolescents. The findings supported H3, indicating that distinct profiles of self-concept clarity exist during adolescence, and that individuals with different profiles exhibit significant differences in their meaning in life.

Specifically, three profiles of self-concept clarity were identified: low self-concept clarity group, moderate self-concept clarity group, and high self-concept clarity group. Among these, the high self-concept clarity group accounted for the smallest proportion (18.09%), while the moderate group was the largest (52.96%). Nearly 30% of adolescents (28.54%) were classified in the low self-concept clarity group. This differentiation of “profiles” further validates the person–context interaction theory (Magnusson & Stattin, 1998), suggesting that the development of self-concept clarity exhibits a diverse pattern. During their self-exploration process, adolescents go through different identity statuses. The low self-concept clarity group may be in an “identity confusion” stage, the high self-concept clarity group may be in an “identity establishment” stage, and the moderate self-concept clarity group may be in a “transitional” stage. The results are consistent with prior study (Xiang et al., 2021), showing a U-shaped distribution of adolescent self-concept clarity, with the majority of adolescents falling in the moderate self-concept clarity profile. This indicates that more than half of adolescents are still in the process of developing their self-concept, and they continue to face the task of refining their self-identity.

In addition, the study found that age group and gender significantly predicted membership in the profiles of self-concept clarity, further supporting previous research (Xiang, 2022). Specifically, compared to junior middle school students, senior high school students and college students were more likely to belong to the moderate or high self-concept clarity groups. Male adolescents were also more likely than female adolescents to be classified in the higher self-concept clarity profiles. These findings are consistent with those obtained from variable-centered analyses, reinforcing the notion that both age and gender influence not only the level of self-concept clarity but also its latent profiles (Xiang et al., 2023). In other words, adolescents at different developmental stages and of different genders might exhibit distinct characteristics and tendencies in the construction and maintenance of self-concept.

Finally, differences were found in overall meaning in life and its dimensions across the different profiles of self-concept clarity, with the high self-concept clarity group reporting the highest levels of meaning in life. This suggests that the profiles of self-concept clarity play an important role in shaping adolescents’ meaning in life. When individuals possess a higher level of self-concept clarity, they are more capable of engaging in self-expansion and understanding the connections between their experiences and behaviors (Emery et al., 2015). Self-concept clarity influences adolescents’ outcome expectations, goal selection, and goal pursuit strategies, making them less susceptible to external disturbances (Jiang et al., 2023; Massey et al., 2008). Moreover, it facilitates a deeper understanding of one’s uniqueness, authenticity, and the significance of one’s existence (Ferris et al., 2009; Koriat, 2012; B. Zhang & Lin, 2023). In addition, individuals in the low self-concept clarity profile had the lowest meaning in life, which suggested that teachers and parents should pay special attention to this group of students. Schools and families can serve as key support systems, providing an environment conducive to adolescents’ self-exploration, helping them enhance their self-concept clarity, and thereby gradually improving their meaning in life as they grow.

4.3. Implications and Limitations

The study, utilizing cross-sectional data, elucidated the relationship between adolescents’ self-concept clarity and meaning in life through both correlation and latent profile analyses. The correlation analysis confirmed a stable positive association between self-concept clarity and meaning in life throughout adolescence, emphasizing the pivotal role of self-concept clarity as a core component of the individual’s self-structure in the development of life meaning. Latent profile analysis revealed multiple subgroups of adolescents characterized by distinct levels of self-concept clarity, further highlighting the significance of individual differences in shaping adolescents’ experience of meaning in life. The identification of such group heterogeneity facilitates more precise mental health assessments and stratified interventions, providing practical pathways for educational practice. However, the study still has some limitations. First, a cross-sectional study cannot establish causal directions between variables, limiting mechanistic explanations of how self-concept clarity influences meaning in life. Second, the lack of tracking intra-individual dynamic changes prevents examination of fluctuations and mutual influences of self-concept clarity and meaning in life over time. Third, cross-sectional data might be affected by confounding variables, compromising the internal validity of the findings. Future research should adopt more diverse methodologies to thoroughly explore the psychological mechanisms underlying the relationship between these constructs, further enrich theoretical models of self-concept clarity and meaning in life, and guide more effective personalized interventions.

5. Conclusions

Several important conclusions emerged from the study. Adolescents’ self-concept clarity is significantly and positively associated with their meaning in life and its various dimensions. Three distinct profiles of self-concept clarity were identified: high, moderate, and low. Both age and gender were significant predictors of adolescents’ membership in these self-concept clarity profiles. Furthermore, the high self-concept clarity group exhibited the highest levels of overall meaning in life, coherence, purpose, and significance, followed by the moderate group, and the low group scoring the lowest across all dimensions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y. and S.G.; methodology, Y.Y.; investigation, Y.Q. and H.W.; formal analysis, Y.Q.; writing—original draft, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y., S.G. and Y.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Henan Educational Science Planning Project [grant number: 2025YB0205].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology of Central China Normal University (approval code: CCNU-IRB-202409055A, 30 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets processed and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding/first author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that might compromise the participants’ privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Battista, J., & Almond, R. (1973). The development of meaning in life. Psychiatry, 36(4), 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błażek, M., & Besta, T. (2012). Self-concept clarity and religious orientations: Prediction of purpose in life and self-esteem. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(3), 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, H. C. (2011). The dialectical self-concept II: Cross-role and within-role consistency, well-being, self-certainty, and authenticity. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(7), 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, H. C. (2021). Social class and self-concept consistency: Implications for subjective well-being and felt authenticity. Self and Identity, 20(3), 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, H. C., Bloch, T., & Pelletier, A. (2016). Fluid compensation following threats to self-concept clarity. Self and Identity, 15(2), 152–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. D., Trapnell, P. D., Heine, S. J., Katz, I. M., Lavallee, L. F., & Lehman, D. R. (1996). Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(1), 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C., & Lowery, B. S. (2024). Perceiving a stable self-concept enables the experience of meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 50(5), 780–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, A. T., Katigbak, M. S., Ibáñez-Reyes, J., De Jesús Vargas-Flores, J., Curtis, G. J., Tanaka-Matsumi, J., Cabrera, H. F., Mastor, K. A., Zhang, H., Shen, J., Locke, K. D., Alvarez, J. M., Ching, C. M., Ortiz, F. A., & Simon, J.-Y. R. (2014). Relating self-concept consistency to hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in eight cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(5), 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S. L., & Muthén, B. (2009). Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. Available online: https://www.statmodel.com/download/relatinglca.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Costanza, A., Prelati, M., & Pompili, M. (2019). The meaning in life in suicidal patients: The presence and the search for constructs. A systematic review. Medicina, 55(8), 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costin, V., & Vignoles, V. L. (2020). Meaning is about mattering: Evaluating coherence, purpose, and existential mattering as precursors of meaning in life judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(4), 864–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E., Rubini, M., Branje, S., Koot, H. M., & Meeus, W. (2016). Self-concept clarity in adolescents and parents: A six-wave longitudinal and multi-informant study on development and intergenerational transmission. Journal of Personality, 84(5), 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekierda, K., Banik, A., Park, C. L., & Luszczynska, A. (2017). Meaning in life and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 11(4), 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, G. C. (1988). Gender differences in self-consistency: Evidence from an investigation of self-concept structure. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17(1), 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, L. F., Walsh, C., & Slotter, E. B. (2015). Knowing who you are and adding to it: Reduced self-concept clarity predicts reduced self-expansion. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(3), 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth in crisis. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., Lian, H., & Keeping, L. M. (2009). When does self-esteem relate to deviant behavior? The role of contingencies of self-worth. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, I. C., Shanahan, M. L., Hirsh, A. T., Stewart, J. C., & Rand, K. L. (2020). The relationship between meaning in life and post-traumatic stress symptoms in US military personnel: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fite, R. E., Lindeman, M. I. H., Rogers, A. P., Voyles, E., & Durik, A. M. (2017). Knowing oneself and long-term goal pursuit: Relations among self-concept clarity, conscientiousness, and grit. Personality and Individual Differences, 108, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L. S., & Park, C. L. (2016). Meaning in life as comprehension, purpose, and mattering: Toward integration and new research questions. Review of General Psychology, 20(3), 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L. S., & Park, C. L. (2017). The multidimensional existential meaning scale: A tripartite approach to measuring meaning in life. Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(6), 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, A. P., & Sedikides, C. (2018). Essential self-evaluation motives: Caring about who we are. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrettaz, J., Chang, L., Hippel, W., Carroll, P. J., & Arkin, R. M. (2014). Self-concept clarity: Buffering the impact of self-evaluative information. Individual Differences Research, 12(4–B), 180–190. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-57870-001 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Gupta, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2020). Future time perspective and group performance among students: Role of student engagement and group cohesion. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 12(5), 1265–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R. (2023). The relationship among parental psychological control, self-concept clarity, and meaning in life in senior high school students and its intervention study [Master’s thesis, Min Nan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Hasson-Ohayon, I., Mashiach-Eizenberg, M., Elhasid, N., Yanos, P. T., Lysaker, P. H., & Roe, D. (2014). Between self-clarity and recovery in schizophrenia: Reducing the self-stigma and finding meaning. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(3), 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, J. A., & King, L. A. (2009). Meaning in life as a subjective judgment and a lived experience. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(4), 638–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilagan, G. (2023). Daily fluctuations in self-concept clarity and emptiness as predictors of nonsuicidal self-injury [Doctoral dissertation, BA, Williams College]. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T., Wang, T., Poon, K.-T., Gaer, W., & Wang, X. (2023). Low self-concept clarity inhibits self-control: The mediating effect of global self-continuity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 49(11), 1587–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, H. S., Richardson, S. A., Golden-Kreutz, D. M., & Andersen, B. L. (2006). Strategies used in coping with a cancer diagnosis predict meaning in life for survivors. Health Psychology, 25(6), 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshanloo, M. (2018). Gender differences in the predictors of life satisfaction across 150 nations. Personality and Individual Differences, 135, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T., & Wickrama, K. A. S. (2008). An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Lee, Y. W., Kim, H., & Lee, E. (2019). The mediating and moderating effects of meaning in life on the relationship between depression and quality of life in patients with dysphagia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(15–16), 2782–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2021). The science of meaning in life. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koriat, A. (2012). The self-consistency model of subjective confidence. Psychological Review, 119(1), 80–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, H., & Güloğlu, B. (2021). The role of uncertainty tolerance and meaning in life on depression and anxiety throughout Covid-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences, 179, 110952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M. W., Chen, S., & Keltner, D. (2011). The power to be me: Power elevates self-concept consistency and authenticity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(5), 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, D. (2018). When is meaning in life most beneficial to young people? Styles of meaning in life and well-being among late adolescents. Journal of Adult Development, 25(2), 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q., Xiang, G., Song, S., Huang, X., & Chen, H. (2022). Examining the associations of trait self-control with hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(2), 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. (2023). The effects of parental attachment and school connectedness on meaning in high school students: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study [Master’s thesis, Guizhou Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Light, A. E. (2017). Self-concept clarity, self-regulation, and psychological well-being. In J. Lodi-Smith, & K. G. DeMarree (Eds.), Self-concept clarity (pp. 177–193). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L. (2021). Longitudinal associations of meaning in life and psychosocial adjustment to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. British Journal of Health Psychology, 26(2), 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Di, S., Zhang, Y., & Ma, C. (2023). Self-concept clarity and learning engagement: The sequence-mediating role of the sense of life meaning and future orientation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodi-Smith, J., Spain, S. M., Cologgi, K., & Roberts, B. W. (2017). Development of identity clarity and content in adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(5), 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P. K., Newman, D. B., Schlegel, R. J., & Wirtz, D. (2023). Authenticity, meaning in life, and life satisfaction: A multicomponent investigation of relationships at the trait and state levels. Journal of Personality, 91(3), 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, D., & Stattin, H. (1998). Person-context interaction theories. In Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 685–759). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, X., Li, F., Wu, B., & Wu, J. (2023). Mindfulness and meaning in life: The mediating effect of self-concept clarity and coping self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 33(3), 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makola, S. (2014). Sense of meaning and study perseverance and completion: A brief report. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 24(3), 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, H. D. (2017). Sense of meaning and academic performance: A brief report. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 27(3), 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, E. K., Gebhardt, W. A., & Garnefski, N. (2008). Adolescent goal content and pursuit: A review of the literature from the past 16 years. Developmental Review, 28(4), 421–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagawa, Y. (2022). Self-compassion promotes self-concept clarity and self-change in response to negative events. Journal of Personality, 92, 1265–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawiak, A., Mrozinski, B., Gutral, J., Cypryańska, M., & Nezlek, J. B. (2018). Self-esteem mediates relationships between self-concept clarity and perceptions of the future. Journal of Education Culture and Society, 9(1), 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G., Sun, X., Zhou, Z., Tian, Y., Li, Q., & Lian, S. (2016). The effect of adolescents’ social networking site use on self-concept clarity: The mediating role of social comparison. Journal of Psychological Science, 31(9), 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A monte carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund-Gibson, K., Garber, A. C., Carter, D. B., Chan, M., Arch, D. A. N., Simon, O., Whaling, K., Tartt, E., & Lawrie, S. I. (2023). Ten frequently asked questions about latent transition analysis. Psychological Methods, 28(2), 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H., & Jeong, D. Y. (2016). Moderation effects of perfectionism and meaning in life on depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2017). Meaning in life and adjustment to daily stressors. Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(4), 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarska, A. (2016). How do self-concept differentiation and self-concept clarity interrelate in predicting sense of personal identity? Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roepke, A. M., Jayawickreme, E., & Riffle, O. M. (2014). Meaning and health: A systematic review. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 9(4), 1055–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. J., Klimstra, T. A., Luyckx, K., Hale, W. W., Frijns, T., Oosterwegel, A., Van Lier, P. A. C., Koot, H. M., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2011). Daily dynamics of personal identity and self–concept clarity. European Journal of Personality, 25(5), 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J. Y., Steger, M. F., & Henry, K. L. (2016). Self-concept clarity’s role in meaning in life among American college students: A latent growth approach. Self and Identity, 15(2), 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M., Wethington, E., & Zhan, G. (1996). Self-concept clarity and preferred coping styles. Journal of Personality, 64(2), 407–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F. (2017). Meaning in life and wellbeing. In M. Slade, L. Oades, & A. Jarden (Eds.), Wellbeing, recovery and mental health (1st ed., pp. 75–85). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., Kawabata, Y., Shimai, S., & Otake, K. (2008). The meaningful life in Japan and the United States: Levels and correlates of meaning in life. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(3), 660–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., Oishi, S., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Meaning in life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(1), 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, W. B. (1997). The trouble with change: Self-verification and allegiance to the self. Psychological Science, 8(3), 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N. M., Hofer, J., & Kranz, D. (2022). Effects of an intergenerational program on adolescent self-concept clarity: A pilot study. Journal of Personality, 90(3), 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsibidaki, A. (2021). Anxiety, meaning in life, self-efficacy and resilience in families with one or more members with special educational needs and disability during COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 109, 103830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğurlar, P., & Wulff, D. U. (2022). Self-concept clarity is associated with social decision making performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 197, 111783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., He, X., & Zhang, D. (2016). Structure and levels of meaning in life and its relationship with mental health in Chinese students aged 10 to 25. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 10, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E., Hopwood, C. J., Nissen, A. T., & Bleidorn, W. (2023). Disentangling self-concept clarity and self-esteem in young adults. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 125(6), 1420–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A. E., & Vallacher, R. R. (2018). Reciprocal feedback between self-concept and goal pursuit in daily life. Journal of Personality, 86(3), 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Watkins, D., & Hattie, J. (2010). Self-concept clarity: A longitudinal study of hong kong adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(3), 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, G. (2022). The influence of self-concept clarity on subjective well-being in adolescents: Behavior and fMRI evidence [Doctoral dissertation, Xi Nan University]. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, G., Chen, H., Wang, Y., & Hou, Q. (2021). The correlation between self-concept clarity and subjective well-being among adolescents: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Southwest University (Social Sciences Edition), 47(2), 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, G., Li, Q., Li, X., & Chen, H. (2023). Development of self-concept clarity from ages 11 to 24: Latent growth models of Chinese adolescents. Self and Identity, 22(1), 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., Zhang, Y., & Yu, G. (2022). Prevalence of mental health problems among senior high school students in mainland of China from 2010 to 2020: A meta-analysis. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(5), 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., & Lin, R. (2023). Dispositional awe and self-worth in Chinese undergraduates: The suppressing effects of self-concept clarity and small self. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. (2018). Self-lost in story: The influence of adolescents’ internet literature reading on self-concept clarity. Central China Normal University. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P., Wang, P., Zhang, D., & Zhang, L. (2022). Effect of self-concept clarity and meaning in life on suicidal ideation in college fresh students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 36(11), 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N., Ma, M., & Xin, Z. (2017). Mental mechanism and the influencing factors of meaning in life. Advances in Psychological Science, 25(6), 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Li, T., Ren, Q., Wang, S., Tong, P., Zheng, Y., & Gao, Y. (2018). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the multidimensional existential meaning scale in college students. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medicine and Brain Science, 27(11), 1043–1046. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).