Bidirectional Relationship Between Insomnia and Depressive Symptoms in Family Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Longitudinal Study †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

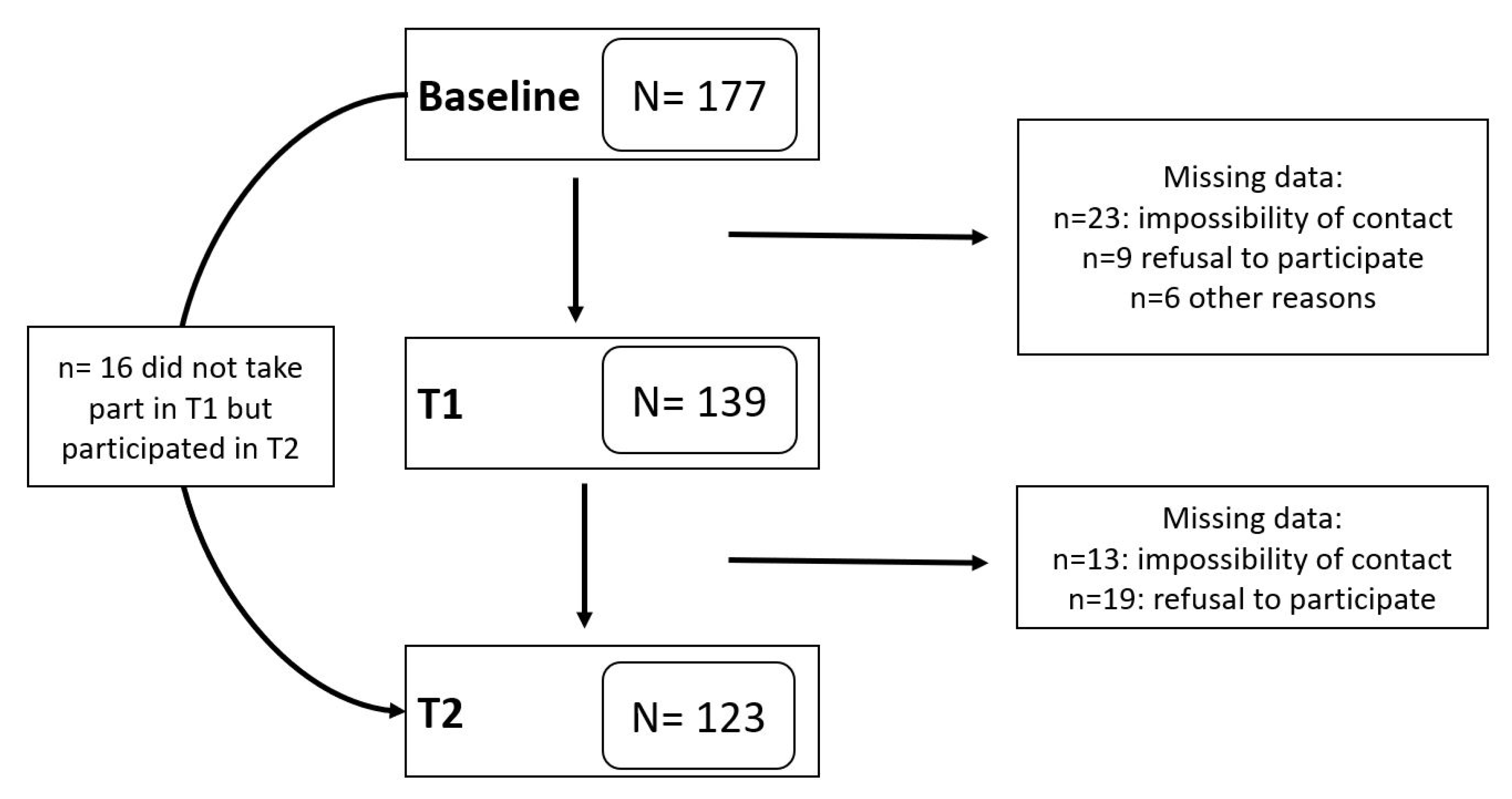

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Variables and Instruments

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Information

2.3.2. Health Behaviors

2.3.3. Medical Data

2.3.4. Caregiver Stressors

2.3.5. Depressive Symptoms

2.3.6. Insomnia Symptoms

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Model 1: Longitudinal Relationship Between Insomnia and Depressive Symptoms

3.3. Model 2: Longitudinal Relationship Between Depressive and Insomnia Symptoms

3.4. Secondary Analyses: Depression and Insomnia Symptoms and Time Since Being a Caregiver

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alvaro, P. K., Roberts, R. M., & Harris, J. K. (2013). A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep, 36(7), 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewster, G. S., Wang, D., McPhillips, M. V., Epps, F., & Yang, I. (2022). Correlates of sleep disturbance experienced by informal caregivers of persons living with dementia: A systematic review. Clinical Gerontologist, 47(3), 380–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodaty, H., & Donkin, M. (2009). Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(2), 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, R. N., & Kishita, N. (2020). Prevalence of depression and burden among informal caregivers of people with dementia: A meta-analysis. Ageing & Society, 40(11), 2355–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H., Tu, S., Sheng, J., & Shao, A. (2019). Depression in sleep disturbance: A review on a bidirectional relationship, mechanisms and treatment. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 23(4), 2324–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, P. L., & Buysse, D. J. (2008). Sleep disturbances and depression: Risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10(8), 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D., Sheaves, B., Waite, F., Harvey, A. G., & Harrison, P. J. (2020). Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(7), 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C., Chapagain, N. Y., & Scullin, M. K. (2019). Sleep duration and sleep quality in caregivers of patients with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 2(8), e199891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R., Helm, A., Ross, I., Gander, P., & Breheny, M. (2023). “I think I could have coped if I was sleeping better”: Sleep across the trajectory of caring for a family member with dementia. Dementia, 22(5), 1038–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, A., Iwasaki, Y., & Honda, S. (2017). The mediating role of sleep quality on well-being among Japanese working family caregivers. Home Health Care Management & Practice, 29(3), 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gonzalo, L., Romero-Moreno, R., Pedros-Chaparro, M. S., Gallego-Alberto, L., Barrera-Caballero, S., Olazarán, J., & Losada-Baltar, A. (2021). Psychometric properties of the insomnia severity index in a sample of family dementia caregivers. Sleep Medicine, 82, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, B. G., & Sayegh, P. (2010). Cultural values and caregiving: The updated sociocultural stress and coping model. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 65(1), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leggett, A. N., Morley, M., & Smagula, S. F. (2020). “It’s been a hard day’s night”: Sleep problems in caregivers for older adults. Current Sleep Medicine Reports, 6(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggett, A. N., Polenick, C. A., Maust, D. T., & Kales, H. C. (2018). “What hath night to do with sleep?”: The caregiving context and dementia caregivers’ nighttime awakenings. Clinical Gerontologist, 41(2), 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinsohn, P. M., Seeley, J. R., Roberts, R. E., & Allen, N. B. (1997). Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychology and Aging, 12, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losada-Baltar, A., De Los Ángeles Villareal, M., Nuevo, R., Márquez-González, M., Salazar, B. C., Romero-Moreno, R., Carrillo, A. L., & Fernández-Fernández, V. (2012). Cross-cultural confirmatory factor analysis of the CES-D in Spanish and Mexican dementia caregivers. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(2), 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M., Dorstyn, D., Ward, L., & Prentice, S. (2018). Alzheimers’ disease and caregiving: A meta-analytic review comparing the mental health of primary carers to controls. Aging & Mental Health, 22(11), 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurry, S. M., Pike, K. C., Vitiello, M. V., Logsdon, R. G., & Teri, L. (2008). Factors associated with concordance and variability of sleep quality in persons with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers. Sleep, 31(5), 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McCurry, S. M., Song, Y., & Martin, J. L. (2015). Sleep in caregivers: What we know and what we need to learn. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 28(6), 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C. M. (1993). Insomnia: Psychological assessment and management. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, C. M., Belleville, G., Bélanger, L., & Ivers, H. (2011). The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep, 34(5), 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales-González, C., Losada, A., & Romero-Moreno, R. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Spanish version of the revised memory and behavior problems checklist. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(4), 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H. L., & Chang, Y. P. (2013). Sleep disturbance in family caregivers of individuals with dementia: A review of the literature. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 49(2), 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H. L., Lorenz, R. A., & Chang, Y. P. (2018). Factors associated with sleep in family caregivers of individuals with dementia. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 55(1), 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, C., & Toms, G. (2019). Influence of positive aspects of dementia caregiving on caregivers’ well-being: A systematic review. The Gerontologist, 59(5), 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafnsson, S. B., Shankar, A., & Steptoe, A. (2017). Informal caregiving transitions, subjective well-being and depressed mood: Findings from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Aging & Mental Health, 21(1), 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Whelen, S., Tada, Y., MacCallum, R. C., McGuire, L., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2001). Long-term caregiving: What happens when it ends? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(4), 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, N., Schulze, J., Kirschbaum, C., Buske-Kirschbaum, A., Penz, M., Wekenborg, M. K., & Walther, A. (2020). Sleep disturbances in major depressive and burnout syndrome: A longitudinal analysis. Psychiatry Research, 286, 112868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R., Beach, S. R., Czaja, S. J., Martire, L. M., & Monin, J. K. (2020). Family caregiving for older adults. Annual Review of Psychology, 71(1), 635–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupbach, J. N., & Sprenger, J. (2011). The logic of explanatory power. Philosophy of Science, 78(1), 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sivertsen, B., Salo, P., Mykletun, A., Hysing, M., Pallesen, S., Krokstad, S., Nordhus, I., & Øverland, S. (2012). The bidirectional association between depression and insomnia: The HUNT study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74(7), 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, A. B., Coon, D., Wisniewski, S., Vance, D., Arguelles, S., Belle, S., Mendelsohn, A., Ory, M., & Haley, W. (2004). Measurement of leisure time satisfaction in family caregivers. Aging & Mental Health, 8(5), 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teri, L., Truax, P., Logsdon, R., Uomoto, J., Zarit, S., & Vitaliano, P. P. (1992). Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: The revised memory and behavior problems checklist. Psychology and Aging, 7, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitaliano, P. P., Brewer, D. D., Katon, W., & Becker, J. (1995). Psychiatric disorders in spouse caregivers of care recipients with Alzheimer’s disease and matched controls: A diathesis-stress model of psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(1), 197. [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano, P. P., Young, H. M., & Zhang, J. (2004). Is caregiving a risk factor for illness? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(1), 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Känel, R., Mausbach, B. T., Ancoli-Israel, S., Dimsdale, J. E., Mills, P. J., Patterson, T. L., Ziegler, M. G., Roepke, S. K., Chattillion, E. A., Allison, M., & Grant, I. (2012). Sleep in spousal Alzheimer caregivers: A longitudinal study with a focus on the effects of major patient transitions on sleep. Sleep, 35(2), 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Känel, R., Mausbach, B. T., Ancoli-Israel, S., Mills, P. J., Dimsdale, J. E., Patterson, T. L., & Grant, I. (2014). Positive affect and sleep in spousal Alzheimer caregivers: A longitudinal study. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 12(5), 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. C., Yip, P. K., & Chang, Y. (2016). Self-efficacy and sleep quality as mediators of perceived stress and memory and behavior problems in the link to dementia caregivers’ depression in Taiwan. Clinical Gerontologist, 39(3), 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, B. T., Welch, K. B., & Galecki, A. T. (2022). Linear mixed models: A practical guide using statistical software. Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Baseline (n = 155) | Year 1 (n = 139) | Year 2 (n = 123) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or Percentage (n)/Scale Range | Mean (SD) or Percentage (n)/Scale Range | Mean (SD) or Percentage (n)/Scale Range | |

| Women, % | 64.50 (100) | 65.00 (91) | 68.03 (83) |

| Age | 62.26 (12.22)/32–87 | 62.70 (11.86)/33–88 | 63.29 (12.21)/34–89 |

| Months caregiving | 51.45 (35.96)/3–180 | 63.28 (35.47)/15–192 | 77.48 (37.73)/27–204 |

| Daily hours of caregiving | 13.18 (8.36)/1–24 | 12.69 (8.87)/0–24 | 11.08 (9.11)/0–35 |

| Caregiving cessation, % | 0 (0) | 20.00 (31) | 29.70 (46) |

| Health problems | 1.96 (1.49)/0–7 | 1.72 (1.47)/0–7 | 1.83 (1.54)/0–8 |

| Hours of exercise per week | 3.23 (4.12)/0–22 | 3.98 (5.16)/0–35 | 3.66 (4.37)/0–18 |

| Leisure activities | 6.30 (2.77)/0–12 | 5.99 (2.83/0–12 | 5.89 (2.80)/0–12 |

| Alcohol intake | 2.97 (4.73)/0–30 | 2.86 (3.85)/0–20 | 3.07 (4.81)/0–24 |

| Smoker, % | 21.30 (33) | 17.40 (27) | 14.20 (22) |

| Medication intake | 0.34 (0.64)/0–3 | 0.36 (0.81)/0–5 | 0.28 (0.52)/0–2 |

| Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementias | 17.57 (14.44)/0–68 | 16.39 (13.80)/0–63 | 14.71 (14.31)/0–53 |

| Depressive symptoms | 15.01 (10.18)/0–44 | 14.62 (10.53)/0–45 | 14.38 (9.70)/0–41 |

| Caregivers with clinically relevant depressive symptoms, % | 37.4 (58) | 37.0 (51) | 38.2 (47) |

| Insomnia symptoms | 6.10 (5.53)/0–25 | 6.76 (5.57)/0–23 | 6.33 (5.37) 0/21 |

| Caregivers with clinically relevant insomnia symptoms, % | 27.5 (42) | 25.0 (34) | 29.3 (36) |

| Variable | Estimate | SE | Df | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Intercept | 23.69 | 3.60 | 175.98 | 6.58 | <0.001 | 16.59 | 30.80 |

| Time | −0.49 | 0.45 | 218.22 | −1.10 | 0.27 | −1.38 | 0.39 |

| Female gender | −0.38 | 1.21 | 148.48 | −0.32 | 0.75 | −2.78 | 2.01 |

| Age at baseline | −0.15 | 0.05 | 172.84 | −2.82 | <0.01 | −0.25 | −0.04 |

| Months caregiving | −0.01 | 0.01 | 129.48 | −0.36 | 0.72 | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| Daily hours caregiving | −0.03 | 0.05 | 315.77 | −0.61 | 0.54 | −0.14 | 0.07 |

| Caregiving cessation | 0.00 | 1.44 | 277.75 | 0.00 | 0.10 | −2.84 | 2.83 |

| Health problems | 0.27 | 0.33 | 306.38 | 0.80 | 0.42 | −0.38 | 0.92 |

| Hours of exercise per week | −0.03 | 0.07 | 287.62 | −0.43 | 0.66 | −0.16 | 0.10 |

| Leisure activities | −0.94 | 0.17 | 316.38 | −5.61 | <0.001 | −1.26 | −0.61 |

| Alcohol intake per month | −0.04 | 0.11 | 297.70 | −0.39 | 0.699 | −0.26 | 0.18 |

| Smoking status | 2.39 | 1.24 | 264.46 | 1.93 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 4.83 |

| Medication intake | 2.31 | 0.72 | 300.12 | 3.22 | <0.01 | 0.90 | 3.72 |

| Behavioral and psychological symptoms | 0.17 | 0.03 | 304.60 | 5.16 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.24 |

| Insomnia symptoms | 0.41 | 0.08 | 313.37 | 4.91 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.57 |

| Variable | Estimate | SE | Df | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Intercept | 7.17 | 2.45 | 182.66 | 2.92 | <0.01 | 2.33 | 12.01 |

| Time | 0.10 | 0.28 | 214.79 | 0.35 | 0.73 | −0.46 | 0.66 |

| Female gender | 0.92 | 0.82 | 151.68 | 1.11 | 0.27 | −0.71 | 2.54 |

| Age at baseline | −0.02 | 0.04 | 180.23 | −0.50 | 0.62 | −0.09 | 0.05 |

| Months caregiving | 0.01 | 0.01 | 133.36 | 1.36 | 0.18 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Daily hours caregiving | 0.02 | 0.03 | 308.91 | 0.63 | 0.53 | −0.05 | 0.09 |

| Caregiving cessation | 0.71 | 0.92 | 262.76 | 0.78 | 0.43 | −1.09 | 2.52 |

| Health problems | 0.39 | 0.21 | 313.06 | 1.81 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.81 |

| Hours of exercise per week | −0.05 | 0.04 | 273.87 | −1.26 | 0.21 | −0.14 | 0.03 |

| Leisure activities | −0.20 | 0.11 | 315.67 | −1.78 | 0.07 | −0.42 | 0.02 |

| Alcohol intake per month | 0.02 | 0.07 | 309.36 | 0.26 | 0.79 | −0.12 | 0.16 |

| Smoking status | −1.77 | 0.82 | 285.42 | −2.16 | <0.05 | −3.38 | −0.16 |

| Medication intake | 1.10 | 0.47 | 308.83 | 2.32 | <0.05 | 0.17 | 2.03 |

| Behavioral and psychological symptoms | −0.01 | 0.02 | 316.80 | −0.60 | 0.55 | −0.06 | 0.03 |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.17 | 0.04 | 315.25 | 4.83 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Gonzalo, L.; Márquez-González, M.; Vara-García, C.; Romero-Moreno, R.; Olazarán, J.; von Känel, R.; Mausbach, B.T.; Losada-Baltar, A. Bidirectional Relationship Between Insomnia and Depressive Symptoms in Family Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Longitudinal Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070936

Jiménez-Gonzalo L, Márquez-González M, Vara-García C, Romero-Moreno R, Olazarán J, von Känel R, Mausbach BT, Losada-Baltar A. Bidirectional Relationship Between Insomnia and Depressive Symptoms in Family Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Longitudinal Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):936. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070936

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Gonzalo, Lucía, María Márquez-González, Carlos Vara-García, Rosa Romero-Moreno, Javier Olazarán, Roland von Känel, Brent T. Mausbach, and Andrés Losada-Baltar. 2025. "Bidirectional Relationship Between Insomnia and Depressive Symptoms in Family Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Longitudinal Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070936

APA StyleJiménez-Gonzalo, L., Márquez-González, M., Vara-García, C., Romero-Moreno, R., Olazarán, J., von Känel, R., Mausbach, B. T., & Losada-Baltar, A. (2025). Bidirectional Relationship Between Insomnia and Depressive Symptoms in Family Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Longitudinal Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070936