Online Interventions for Family Carers of People with Dementia That Focus on Support Strategies for Daily Living: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Items

2.6. Quality Appraisal

2.7. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

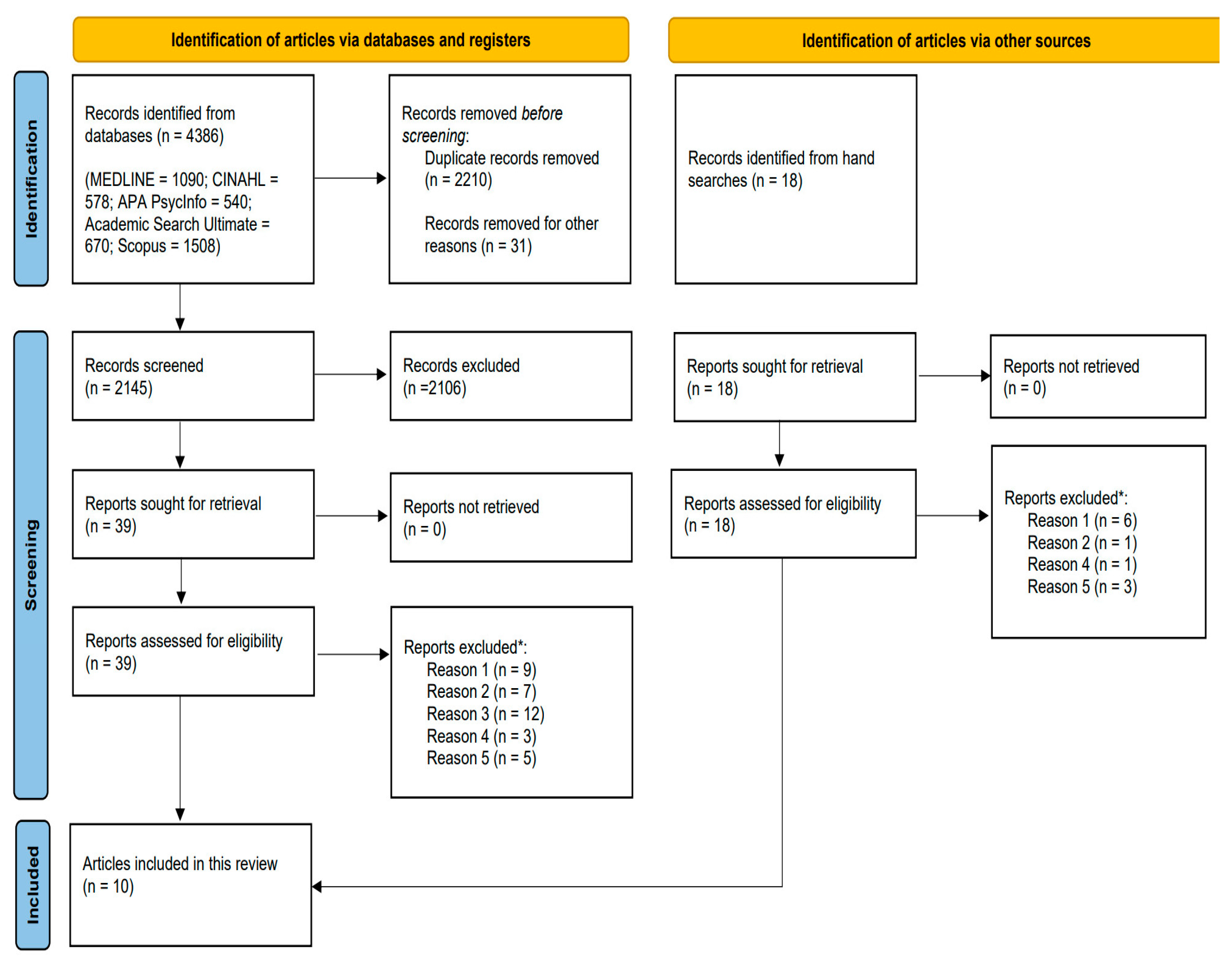

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies and Quality of the Evidence

4. Results of Syntheses

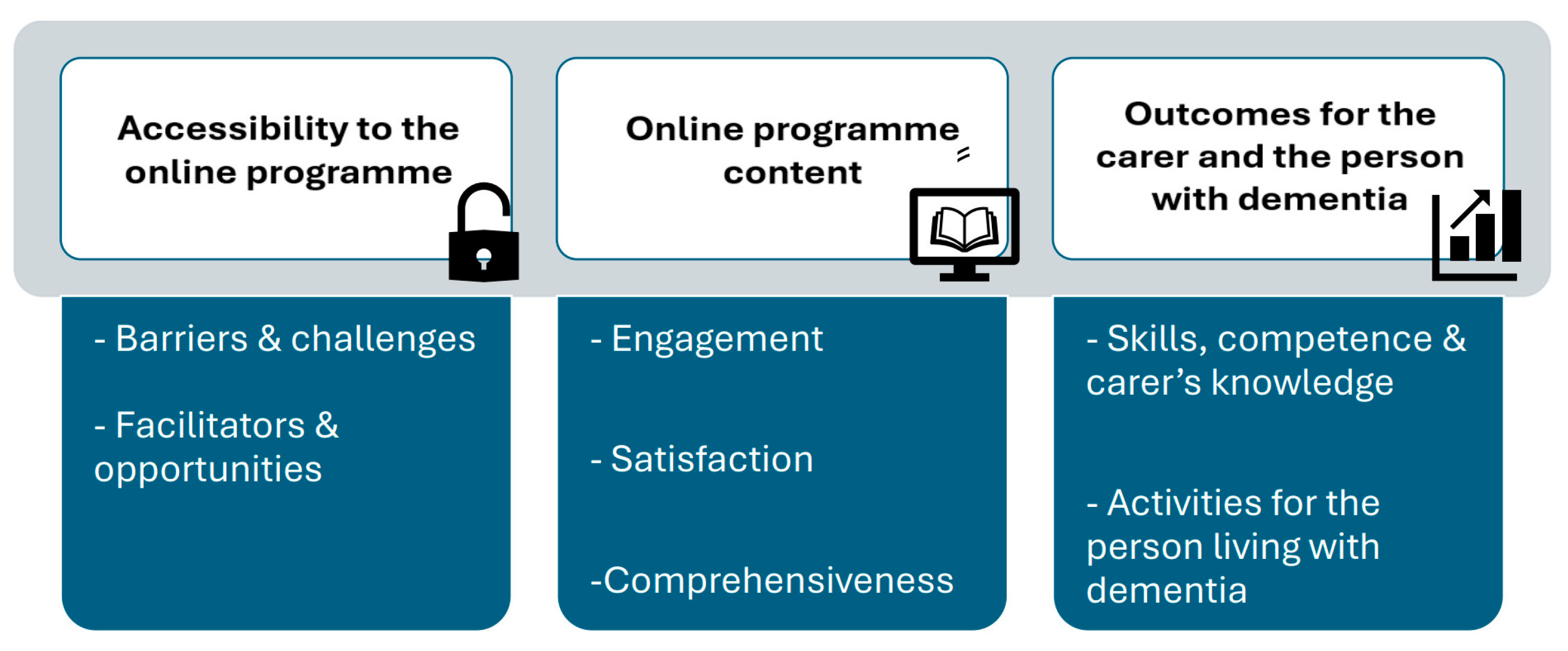

4.1. Accessibility to the Online Programme

4.2. Online Programme Content

4.3. Outcome for the Carer and the Person with Dementia

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. S2), 7412410010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., & Jordan, Z. (Eds.). (2024). JBI Manual for evidence synthesis. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Aspvall, K., Andersson, E., Melin, K., Norlin, L., Eriksson, V., Vigerland, S., Jolstedt, M., Silverberg-Mörse, M., Wallin, L., Sampaio, F., Feldman, I., Bottai, M., Lenhard, F., Mataix-Cols, D., & Serlachius, E. (2021). Effect of an internet-delivered stepped-care program vs. in-person cognitive behavioral therapy on obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms in children and adolescents: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 325(18), 1863–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T. H., Habibi, N., Aromataris, E., Stone, J. C., Leonardi-Bee, J., Sears, K., Hasanoff, S., Klugar, M., Tufanaru, C., Moola, S., & Munn, Z. (2024). The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias quasi-experimental studies. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 22(3), 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, T. H., Stone, J. C., Sears, K., Klugar, M., Tufanaru, C., Leonardi-Bee, J., Aromataris, E., & Munn, Z. (2023). The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for randomized controlled trials. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 21(3), 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beentjes, K. M., Neal, D. P., Kerkhof, Y. J. F., Broeder, C., Moeridjan, Z. D. J., Ettema, T. P., Pelkmans, W., Muller, M. M., Graff, M. J. L., & Dröes, R. M. (2023). Impact of the FindMyApps program on people with mild cognitive impairment or dementia and their caregivers; an exploratory pilot randomised controlled trial. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 8(3), 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S., Laver, K., Voigt-Radloff, S., Letts, L., Clemson, L., Graff, M., Wiseman, J., & Gitlin, L. (2019). Occupational therapy for people with dementia and their family carers provided at home: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 9(11), e026308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boots, L. M., de Vugt, M. E., Kempen, G. I., & Verhey, F. R. (2018). Effectiveness of a blended care self-management program for caregivers of people with early-stage dementia (partner in balance): Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(7), e10017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, V., Visintini, C., & Palese, A. (2020). What do family caregivers of people with dementia need? A mixed-method systematic review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(6), 1942–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodaty, H., Thomson, C., Thompson, C., & Fine, M. (2005). Why caregivers of people with dementia and memory loss don’t use services. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(6), 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burridge, G., Amato, C., Bye, R., Basic, D., Ní Chróinín, D., Hill, S., Howe, K., & Liu, K. P. Y. (2024). Strategies adopted by informal carers to enhance participation in daily activities for persons with dementia. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 43(4), 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary & Thesaurus. (2020). Skill. Cambridge University Press. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/skill (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Camino, J., Kishita, N., Bregola, A., Rubinsztein, J., Khondoker, M., & Mioshi, E. (2021). How does carer management style influence the performance of activities of daily living in people with dementia? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 36(12), 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camino, J., Trucco, A. P., Kishita, N., Mioshi, E., & Backhouse, T. (2024). How do family carers assist people with dementia? A qualitative observation study of daily tasks. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 87(12), 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cepoiu-Martin, M., Tam-Tham, H., Patten, S., Maxwell, C. J., & Hogan, D. B. (2016). Predictors of long-term care placement in persons with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(11), 1151–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C., Slaughter, S., Jones, C., & Wagg, A. (2015). Greater independence in activities of daily living is associated with higher health-related quality of life scores in nursing home residents with dementia. Healthcare, 3(3), 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristancho-Lacroix, V., Wrobel, J., Cantegreil-Kallen, I., Dub, T., Rouquette, A., & Rigaud, A. S. (2015). A web-based psychoeducational program for informal caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(5), e117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J., Hahn-Pedersen, J. H., Eichinger, C. S., Freeman, C., Clark, A., Tarazona, L. R. S., & Lanctôt, K. (2023). Exploring the relationship between patient-relevant outcomes and Alzheimer’s disease progression assessed using the clinical dementia rating scale: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Neurology, 14, 1208802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, A., Bowes, A., Kelly, F., Velzke, K., & Ward, R. (2015). Evidence of what works to support and sustain care at home for people with dementia: A literature review with a systematic approach. BMC Geriatrics, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, S. T., Harrell, E., Neumann, C., & Houtz, A. (2003). The relationship between neuropsychological performance and daily functioning in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease: Ecological validity of neuropsychological tests. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 18(6), 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, J., Knight, A., Marinopoulos, S., Gibbons, M. C., Berger, Z., Aboumatar, H., Wilson, R. F., Lau, B. D., Sharma, R., & Bass, E. B. (2012). Enabling patient-centered care through health information technology. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, (206), 1–1531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gaugler, J. E., Kane, R. L., & Kane, R. A. (2002). Family care for older adults with disabilities: Toward more targeted and interpretable research. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 54(3), 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaugler, J. E., Kane, R. L., Kane, R. A., Clay, T., & Newcomer, R. (2003). Caregiving and institutionalization of cognitively impaired older people: Utilizing dynamic predictors of change. The Gerontologist, 43(2), 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georges, J., Jansen, S., Jackson, J., Meyrieux, A., Sadowska, A., & Selmes, M. (2008). Alzheimer’s disease in real life—The dementia carer’s survey. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(5), 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, S., Adam, S., Olivier, C., Cash, H., Ousset, P. J., Andrieu, S., Vellas, B., Meulemans, T., Reynish, E., Salmon, E., & ICTUS-EADC Network. (2009). Does cognitive impairment influence burden in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease? Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 17(1), 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, L. N., Winter, L., Burke, J., Chernett, N., Dennis, M. P., & Hauck, W. W. (2008). Tailored activities to manage neuropsychiatric behaviors in persons with dementia and reduce caregiver burden: A randomized pilot study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(3), 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, M. J., Vernooij-Dassen, M. J., Thijssen, M., Dekker, J., Hoefnagels, W. H., & Rikkert, M. G. (2006). Community based occupational therapy for patients with dementia and their care givers: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 333(7580), 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P. C., Kovaleva, M., Higgins, M., Langston, A. H., & Hepburn, K. (2018). Tele-Savvy: An online program for dementia caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 33(5), 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattink, B., Meiland, F., van der Roest, H., Kevern, P., Abiuso, F., Bengtsson, J., Giuliano, A., Duca, A., Sanders, J., Basnett, F., Nugent, C., Kingston, P., & Dröes, R. M. (2015). Web-based STAR E-learning course increases empathy and understanding in dementia caregivers: Results from a randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(10), e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, L. J., Glynn, S. M., Hahn, T. J., Randall, F., & Randolph, E. (2012). The use of Internet technology for psychoeducation and support with dementia caregivers. Psychological Services, 9(2), 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, K. W., Lewis, M., Sherman, C. W., & Tornatore, J. (2003). The savvy caregiver program: Developing and testing a transportable dementia family caregiver training program. Gerontologist, 43(6), 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, N., & Gitlin, L. (2021). Implementing and sustaining family care programs in real-world settings: Barriers and facilitators. In J. E. Gaugler (Ed.), Bridging the family care gap (pp. 179–219). Academic Press. ISBN 9780128138984. [Google Scholar]

- Holt Clemmensen, T., Hein Lauridsen, H., Andersen-Ranberg, K., & Kaae Kristensen, H. (2021). Informal carers’ support needs when caring for a person with dementia—A scoping literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 35(3), 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House of Commons All-Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia. (2011). The £20 billion question: An inquiry into improving lives through cost effective dementia services. Available online: http://alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=1154 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Jönsson, L., Eriksdotter Jönhagen, M., Kilander, L., Soininen, H., Hallikainen, M., Waldemar, G., Nygaard, H., Andreasen, N., Winblad, B., & Wimo, A. (2006). Determinants of costs of care for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(5), 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, S., Lafortune, L., Hart, N., Cowan, K., Fenton, M., & Brayne, C. (2015). Dementia priority setting partnership. Dementia priority setting partnership with the james lind alliance: Using patient and public involvement and the evidence base to inform the research agenda. Age and Ageing, 44(6), 985–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhof, Y., Kohl, G., Veijer, M., Mangiaracina, F., Bergsma, A., Graff, M., & Dröes, R. M. (2022). Randomized controlled feasibility study of FindMyApps: First evaluation of a tablet-based intervention to promote self-management and meaningful activities in people with mild dementia. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 17(1), 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishita, N., Hammond, L., Dietrich, C. M., & Mioshi, E. (2018). Which interventions work for dementia family carers? An updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials of carer interventions. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(11), 1679–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, M., Zhao, Y., Xiao, H., Li, C., & Wang, Z. (2020). Internet-based supportive interventions for family caregivers of people with dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e19468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. L., Hobday, J. V., & Hepburn, K. W. (2010). Internet-based program for dementia caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 25(8), 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarondo, L., Stern, C., Carrier, J., Godfrey, C., Rieger, K., Salmond, S., Apostolo, J., Kirkpatrick, P., & Loveday, H. (2020). Chapter 8: Mixed methods systematic reviews. In E. Aromataris, C. Lockwood, K. Porritt, B. Pilla, & Z. Jordan (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis (2024). Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355829175/8.+Mixed+methods+systematic+reviews (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Lockwood, C., Munn, Z., & Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourida, I., Abbott, R. A., Rogers, M., Lang, I. A., Stein, K., Kent, B., & Thompson Coon, J. (2017). Dissemination and implementation research in dementia care: A systematic scoping review and evidence map. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppa, M., Luck, T., Weyerer, S., König, H. H., Brähler, E., & Riedel-Heller, S. G. (2010). Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A systematic review. Age and Ageing, 39(1), 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M., You, E., & Tatangelo, G. (2016). Hearing their voice: A systematic review of dementia family caregivers’ needs. Gerontologist, 56(5), e70–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKechnie, V., Barker, C., & Stott, J. (2014). The effectiveness of an Internet support forum for carers of people with dementia: A pre-post cohort study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(2), e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiland, F., Innes, A., Mountain, G., Robinson, L., van der Roest, H., García-Casal, J. A., Gove, D., Thyrian, J. R., Evans, S., Dröes, R. M., Kelly, F., Kurz, A., Casey, D., Szcześniak, D., Dening, T., Craven, M. P., Span, M., Felzmann, H., Tsolaki, M., & Franco-Martin, M. (2017). Technologies to support community-dwelling persons with dementia: A position paper on issues regarding development, usability, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, deployment, and ethics. JMIR Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies, 4(1), e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, D. C., Riper, H., & Schueller, S. M. (2018). A solution-focused research approach to achieve an implementable revolution in digital mental health. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(2), 113–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, D. C., Schueller, S. M., Montague, E., Burns, M. N., & Rashidi, P. (2014). The behavioral intervention technology model: An integrated conceptual and technological framework for eHealth and mHealth interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(6), e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S., Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., Aromataris, E., Sears, K., Sfetcu, R., Currie, M., Qureshi, R., Mattis, P., Lisy, K., & Mu, P.-F. (2020). Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In E. Aromataris, & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Murray, E., Burns, J., See, T. S., Lai, R., & Nazareth, I. (2005). Interactive health communication applications for people with chronic disease (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4), CD004274. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, D. P., Ettema, T. P., Zwan, M. D., Dijkstra, K., Finnema, E., Graff, M., Muller, M., & Dröes, R. M. (2023). FindMyApps compared with usual tablet use to promote social health of community-dwelling people with mild dementia and their informal caregivers: A randomised controlled trial. EClinical Medicine, 63, 102169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, D. P., Kucera, M., van Munster, B. C., Ettema, T. P., Dijkstra, K., Muller, M., Dröes, R. M., & Bosmans, J. E. (2024). Cost-effectiveness of the FindMyApps eHealth intervention vs. digital care as usual: Results from a randomised controlled trial. Aging and Mental Health, 28(11), 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Naveira, L., Alonso-Búa, B., de Labra, C., Gregersen, R., Maibom, K., Mojs, E., Krawczyk-Wasielewska, A., & Millán-Calenti, J. C. (2016). UnderstAID, an ICT Platform to help informal caregivers of people with dementia: A pilot randomized controlled study. BioMed Research International, 2016, 5726465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hrobjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Vidales, E., Soto-Pérez, F., Perea-Bartolomé, M. V., Franco-Martín, M. A., & Muñoz-Sánchez, J. L. (2017). Online interventions for caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría, 45(3), 116–126. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin, L. I., & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19(1), 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, M., & Jackson, J. (2009). World alzheimer report 2009: The global prevalence of dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International. Available online: https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer-report-2009/ (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Reed, C., Belger, M., Vellas, B., Andrews, J. S., Argimon, J. M., Bruno, G., Dodel, R., Jones, R. W., Wimo, A., & Haro, J. M. (2016). Identifying factors of activities of daily living important for cost and caregiver outcomes in Alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(2), 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheibl, F., Boots, L., Eley, R., Fox, C., Gracey, F., Harrison Dening, K., Oyebode, J., Penhale, B., Poland, F., Ridel, G., West, J., & Cross, J. L. (2024). Adapting a dutch Web-based intervention to support family caregivers of people with dementia in the UK context: Accelerated experience-based co-design. JMIR Formative Research, 8, e52389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, M. R., & Wojtczak, A. (2002). Global minimum essential requirements: A road towards competence-oriented medical education. Medical Teacher, 24(2), 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaff, M. M., & Pearlin, L. I. (1992). Caregiving: Role engulfment and the loss of self. Gerontologist, 32(5), 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takechi, H., Kokuryu, A., Kuzuya, A., & Matsunaga, S. (2019). Increase in direct social care costs of Alzheimer’s disease in Japan depending on dementia severity. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 19(10), 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Roest, H. G., Meiland, F. J., Jonker, C., & Dröes, R. M. (2010). User evaluation of the DEMentia-specific digital interactive social chart (DEM-DISC). A pilot study among informal carers on its impact, user friendliness and usefulness. Aging and Mental Health, 14(4), 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mierlo, L. D., Meiland, F. J., Van de Ven, P. M., Van Hout, H. P., & Dröes, R. M. (2015). Evaluation of DEM-DISC, customized e-advice on health and social support services for informal carers and case managers of people with dementia; a cluster randomized trial. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(8), 1365–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernooij-Dassen, M. J., Felling, A. J., Brummelkamp, E., Dauzenberg, M. G. H., Van Den Bos, G. A. M., & Grol, R. (1999). Assessment of caregiver’s competence in dealing with the burden of caregiving for a dementia patient: A short sense of competence questionnaire (SSCQ) suitable for clinical practice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 47, 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernooij-Dassen, M. J., Persoon, J. M., & Felling, A. J. (1996). Predictors of sense of competence in caregivers of demented persons. Social Science & Medicine, 43(1), 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikström, S., Borell, L., Stigsdotter-Neely, A., & Josephsson, S. (2005). Caregivers’ self-initiated support toward their partners with dementia when performing an everyday occupation together at home. OTJR, 25(4), 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimo, A., Seeher, K., Cataldi, R., Cyhlarova, E., Dielemann, J. L., Frisell, O., Guerchet, M., Jönsson, L., Malaha, A. K., Nichols, E., Pedroza, P., Prince, M., Knapp, M., & Dua, T. (2023). The worldwide costs of dementia in 2019. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 19(7), 2865–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (2012). Definitions of occupational therapy. WFOT. Available online: https://wfot.org/about/about-occupational-therapy (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- World Health Organisation (WHO). (2021). Global status report on the public health response to dementia Geneva. World Health Organisation.

| Programme, Author, Year & Country | Study Design | Carer Sample (Started/Finished) | PwD Sample | Carers’ Age (SD) | Carers’ Gender (Female %) | Relationship | PwD’s Age (SD) | PwD’s Gender (Female %) | Dementia Subtype (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diapason Cristancho-Lacroix et al. (2015) France | Pilot RCT + acceptability | I: 25/17 C: 24/20 | N/A | I: 64.2 (10.3) C: 59.0 (12.4) | I: 64% C: 67% | I: Spouses: 36%; Children: 64% C: Spouses: 46%; Children: 54% | N/A | N/A | AD: 100% |

| Internet-Based Savvy Caregiver Lewis et al. (2010) USA | Development + Feasibility | I: 47 No control group | N/A | I: 55 (9) | I: 85% | N/R | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| UnderstAID Núñez-Naveira et al. (2016) Spain, Poland & Denmark | Pilot RCT | I: 36/30 C: 41/31 | N/A | Range 25–88 years No mean reported I or C: N/R | I: 70% C: 58.1% | All: no consanguinity (47.8%); with consanguinity (52.2%) I or C: N/R | N/A | N/A | AD: 53%; Other: N/R |

| DEM-DISC van der Roest et al. (2010) The Netherlands | Pilot pretest–posttest control group | I:14 C:14 | I: 12/9 C: 11/11 | I:60.2 (14.3) C: 69.9 (13.2) | I: 64.3% C: 92.9% | I: Spouse: 14.3%; Child: 64.3%; Others: 21.4% C: Spouse: 64.3%; Child: 21.4%; Others: 14.3% | I: 83.3 (6.2) C: 80.6 (4.4) | I: 21.4% C: 71.4% | I: AD: 50% VD: 7.2%; MD: 21.4%; Other: 21.4% C: AD: 57.1%; VD:14.3%; MD: 21.4%; Other: 7.2% |

| DEM-DISC van Mierlo et al. (2015) The Netherlands | RCT | I: 41/38/30 (dyads) C: 32/26/19 (dyads) * | N/A | I: 63.0 (11.6) C: 60.4 (12.7) | I: 61.0% C: 50.0% | I: Spouse: 36.6%; Child: 53.7% C: Spouse: 31.2%; Child: 56.2% | I: 82.1 (7.3) C: 79.5 (7.9) | I: 78% C: 65.6% | I: AD: 43.9%; VD: 12.2%; MD: 14.6% Other: 29.3% C: AD: 43.8%; VD: 15.6%; MD: 15.6%; Other: 25% |

| STAR E-Learning Hattink et al. (2015) The Netherlands & UK | RCT | I: 27 (laypeople, includes volunteers and family carers) C: 32 (laypeople) | N/A | I: 52.93 (11.43) C: 54.69 (14.36) | I: 74% C: 69% | I: Partner: 33%; Child 30%; Other: 15%; NA 22% (volunteers) C: Partner 28%; Child 16%; Other 33%; NA 22% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| FindMyApps Kerkhof et al. (2022) The Netherlands | Exploratory Feasibility RCT | I: 10/7 C: 10/7 | I: 7 C: 4 | I: 63.0 (11.8) C: 61.0 (11.7) | I: 100% C: 86% | I: Spouse: 86%; Child: 14% C: Spouse: 57%; Child: 43% | I: 68.9 (14.0) C: 76.0 (4.2) | I: 86% C: 50% | I: AD: 43%; VD: 29%; Other: 28% C: AD: 25%; Other: 75% |

| FindMyApps Beentjes et al. (2023) The Netherlands | Exploratory Pilot RCT | I: 28/25 C: 30/22 | I:27/25 C:28/22 | I: 65.61 (10.19) C: 68.03 (11.67) | I: 71.4% C: 58% | I: Partner: 82.1%; Child: 14.2%; Other: 3.6% C: Partner: 87%; Child: 13% | I: 72.71 (7.78) C: 71.74 (9.64) | I: 57% C: 64.5% | I: 2. AD 61% 3. VD 11% 5. Other 28% C: AD: 51.6%; VD: 12.9%: Other: 35.5% |

| FindMyApps Neal et al. (2023) The Netherlands | Superiority RCT | I: 76/64 (dyads) C: 74/64 (dyads) ** | I: 64.48 (11.65) C: 61.31 (14.58) | I: 71% C: 76% | I: Partner: 73%; Child: 17%; Other: 10% C: Partner: 72%; Children: 19%; Other: 10% | I: 72.61 (9.51) C: 72.06 (9.22) | I: 55% C: 58% | I: AD: 67%; VD: 19%; Other: 14% C: AD: 47%; VD: 3%: Other: 50% | |

| FindMyApps Neal et al. (2024) The Netherlands | Cost-effectiveness RCT | I: 76 (dyads) C: 74 (dyads) ** | I: 65.37 (11.45) C: 62.5 (14.31) | I: 71.05% C: 75.68% | N/R | I: 73.2 (9.48) C: 72.42 (8.77) | I: 44.74% C: 39.19% | Dementia & MCI It does not specify % | |

| Programme Name Author, Year & Country | Description and Content | Outcome Measures (Who & Type) (Name & Article When Needed) | Frequency | Mode of Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diapason Cristancho-Lacroix et al. (2015) France | The Diapason is a fully automated website that includes twelve sessions. Each session provides theoretical and practical information using videos of health professionals, and a practice guide to apply the content to real life situations. Sessions included information about carer stress, understanding the condition and supporting the person with dementia to maintain and improve their autonomy and safety. Other topics included communication, dealing with behaviours, social and financial support, pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments and the future. Non-mandatory sections included a forum and sections about life experiences and relaxation techniques. One session per week had to be viewed entirely at least once to unblock the next session viewed. | Knowledge about Alzheimer’s Disease (Carer, non-standardised) | Weekly sessions - 15 to 30 mins average & Unlimited access | Online plus online forum to post messages |

| Internet-Based Savvy Caregiver (IBSC) Lewis et al. (2010) USA | The IBSC was developed as a browser-based computer programme, accessible from any internet-connected computer from a psychoeducational intervention called The Savvy Caregiver Program (Hepburn et al., 2003). Four modules were adapted from this programme: effects of dementia on thinking, taking charge and letting go, providing practical help and managing daily care and difficult behaviour. The programme also provided participants with videotaped conversations between people living with dementia and their carers where they discussed and shared their own stories. Content also included written information about the topics and strategies for carers. A written document with all the content plus descriptions of the videos and instructions about the platform were given to participants. | Caregiving Knowledge & Skills (Carer, non-standardised) | Not reported | Online only |

| UnderstAID Núñez-Naveira et al. (2016) Spain, Poland and Denmark | The understAID is an application that can be accessed through any device with internet connection such as a smartphone or tablet or through a browser in a personal computer. The application contains different sections (Learning, Daily Task and a Social Network Section) with different information and functions. The Learning area includes five modules with topics including cognitive decline, daily tasks, behavioural changes, social activities and the role of the carer. The content is displayed using text, videos and images and provides links to other websites. The Daily Task section provides a calendar and reminders for appointments and medication. The Social Network section offers a moderated space for carers to interact with other participants to exchange information and suggestions. The understAID offers tailored information using an interactive questionnaire to determine the level of care the person needs, preferences and time available. | Competence (Carers, standardised) CCS | Not reported | Online plus weekly or monthly phone calls (to monitor progress) |

| STAR E-learning Hattink et al. (2015) The Netherlands and UK | The STAR training portal is a web platform accessible through any internet-based device. It offers an online course with eight modules containing different topics, including information about dementia, diagnosis and daily tasks. It also provides information about communication, behaviours and mood and offers strategies to cope with the condition. The platform uses text, videos and each module offers interactive exercises and knowledge tests in addition to links to other websites. | Knowledge about Alzheimer’s Disease (Carer, standardised) ADKS Competence (Carer, standardised) SSCQ | Own pace | Online only |

| Dementia-specific Digital Interactive Social Chart (DEM-DISC) * van der Roest et al. (2010) van Mierlo et al. (2015) The Netherlands | DEM-DISC is an internet-based social chart system that provides general and tailored information on available dementia care and welfare services that can be found in specific areas of Amsterdam. DEM-DISC uses a three-step procedure to guide users in understanding their needs. Whenever they had questions about dementia or related needs or care and welfare services, carers in the experimental group could consult DEM-DISC by accessing the system on their own personal computers. The DEM-DISC system provides information on dementia diagnosis, practical support, coping, and finding company. DEM-DISC was adapted (van Mierlo et al., 2015) to be more accessible for the customers. As part of the changes made, users can answer questions about their situation (e.g., severity of dementia, living situation) to offer tailored information about health, care and welfare services for both the person living with dementia and their carers. | Knowledge about care and services (Carer, non-standardised) (van der Roest et al., 2010) Competence (Carer, standardised) SSCQ (both articles) | Not reported | Online plus phone calls for check ups |

| FindMyApps ** Kerkhof et al. (2022) Beentjes et al. (2023) Neal et al. (2023) Neal et al. (2024) The Netherlands | FindMyApps is a web application where users have access to a database containing pre-selected apps (an app ‘library’). This library contains approximately 180 apps in the domains of self-management and meaningful activities which were assessed as dementia-friendly apps. The apps contain information about self-management and meaningful activities which are considered as dementia-friendly apps. Both the people with dementia and their carers received a 30-min training session on the use of the tablet and the FindMyApps app. Carers were shown how to support their family members using the tablet and the app. Dyads were suggested to practise at least twice a week for the first month. A video with information about the tablet’s functions was shown to participants. This was located in the project’s website for the duration of the intervention. A printed manual was also given to participants with written instructions about the tablet and app and with a list of links to websites with suggested apps for people with dementia or cognitive impairment. | Competence (Carer, SSCQ, standardised) (all articles) Social Participation (PwD, standardised) MSPP (Neal et al., 2024; Beentjes et al., 2023; Neal et al., 2023) ASCOT (Beentjes et al., 2023) Self-Management Abilities (PwD, standardised) SMAS-S (Beentjes et al., 2023) SMAS-30 (Kerkhof et al., 2022) ASCOT (Neal et al., 2023) Participation in daily and social activities (PwD, Standardised) ASCOT (one item) (Kerkhof et al., 2022) PAL (Kerkhof et al., 2022; Neal et al., 2023) Experienced Autonomy (PwD, standardised) EA (Kerkhof et al., 2022; Neal et al., 2023) Health Status-QoL-ADLs (PwD, standardised) EQ-5D-5L (Neal et al., 2024) | On demand | Online plus help desk available, by email or telephone, at any time. Follow-up phone calls with informal carers took place every couple of weeks to provide support if needed. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Camino, J.; Trucco, A.P.; McArthur, V.; Sugarhood, P. Online Interventions for Family Carers of People with Dementia That Focus on Support Strategies for Daily Living: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 863. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070863

Camino J, Trucco AP, McArthur V, Sugarhood P. Online Interventions for Family Carers of People with Dementia That Focus on Support Strategies for Daily Living: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):863. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070863

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamino, Julieta, Ana Paula Trucco, Victoria McArthur, and Paul Sugarhood. 2025. "Online Interventions for Family Carers of People with Dementia That Focus on Support Strategies for Daily Living: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 863. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070863

APA StyleCamino, J., Trucco, A. P., McArthur, V., & Sugarhood, P. (2025). Online Interventions for Family Carers of People with Dementia That Focus on Support Strategies for Daily Living: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 863. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070863