Drivers and Moderators of Social Media-Enabled Cooperative Learning in Design Education: An Extended TAM Perspective from Chinese Students

Abstract

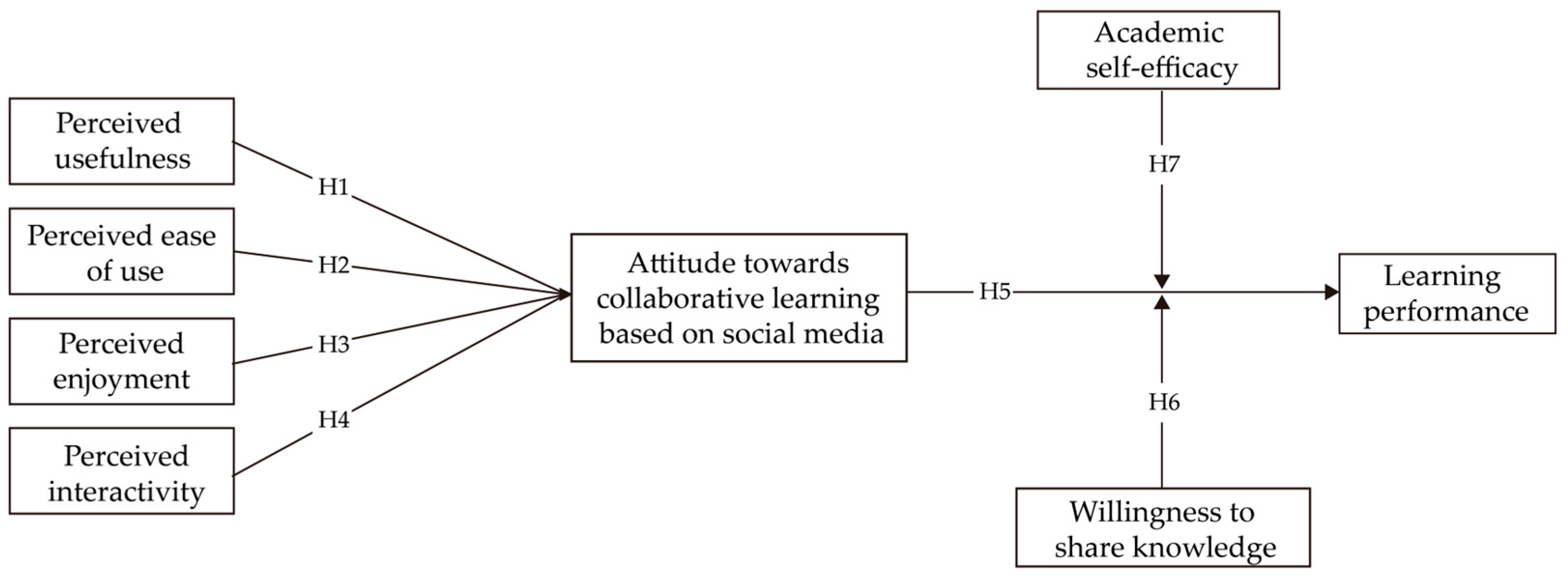

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Model

2.1. Technology Acceptance Model

2.2. Perceived Usefulness

2.3. Perceived Ease of Use

2.4. Perceived Enjoyment

2.5. Perceptual Interactivity

2.6. Attitude Towards Cooperative Learning Based on Social Media and Learning Performance

2.7. The Willingness to Share Knowledge

2.8. Academic Self-Efficacy

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measurement Development

3.2.1. Perceived Usefulness Scale

3.2.2. Perceived Ease of Use Scale

3.2.3. Perceived Enjoyment Scale

3.2.4. Perceptual Interactivity Scale

3.2.5. Social Media-Based Cooperative Learning Willingness Scale

3.2.6. Willingness to Share Knowledge Scale

3.2.7. Academic Self-Efficacy Scale

3.2.8. Learning Performance Scale

3.3. Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Test

4.2. Dependability, Convergent Accuracy, and Discriminant Accuracy

4.3. Model Testing

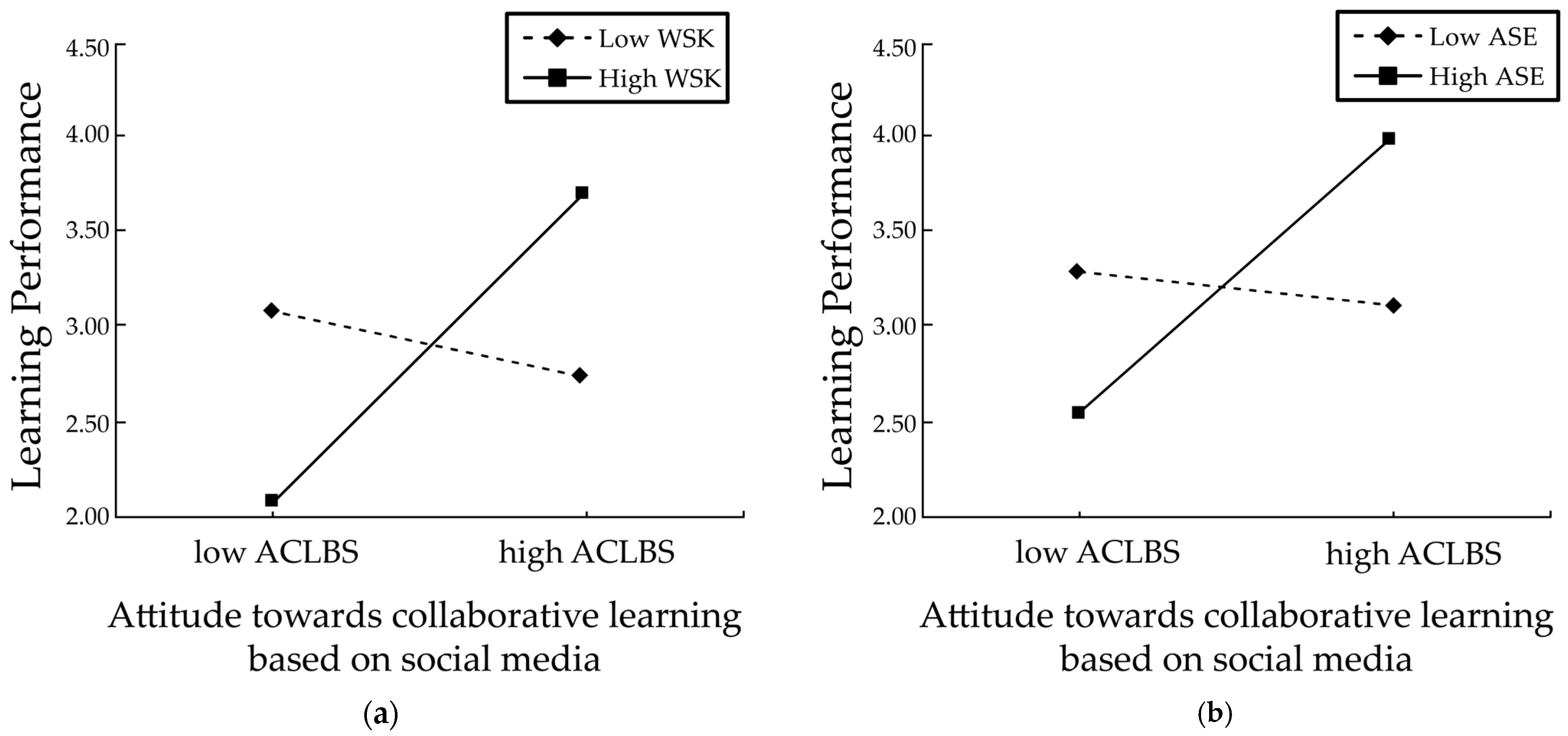

4.4. Moderating Effects Test

4.4.1. Moderating Role of the Willingness to Share Knowledge

4.4.2. Moderating Role of Academic Self-Efficacy

5. Discussion

5.1. Factors Influencing College Students’ Attitude Towards Cooperative Learning Based on Social Media

5.2. Relationships Between the Attitude Towards Cooperative Learning Based on Social Media and Academic Performance

5.3. Moderating Effects of the Willingness to Share Knowledge and Academic Self-Efficacy

5.4. Research Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items | References |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived usefulness, PU | ||

| PU1 | When using social media for cooperative learning, my cooperative performance is better. | (Rauniar et al., 2014; Sarwar et al., 2019) |

| PU2 | Using social media for cooperative learning has improved my cooperative efficiency. | |

| PU3 | I find it useful to use social media for cooperative learning. | |

| Perceived Ease of Use, PEU | ||

| PEU1 | The operation of using social media for cooperative learning is simple. | (Rauniar et al., 2014; Sarwar et al., 2019) |

| PEU2 | I can flexibly interact with group members using social media platforms. | |

| PEU3 | I have no questions about the functions of using social media for group cooperative learning. | |

| Perceived enjoyment, PE | ||

| PE1 | Using social media for group cooperation has brought me novel experiences. | (Davis et al., 1992) |

| PE2 | When using social media for cooperative learning, the communication atmosphere among my group members and me is very relaxed. | |

| PE3 | Using cooperative learning tools in social media allows me to complete learning tasks more easily. | |

| Perceived Interactivity, PI | ||

| PI1 | When using social media for cooperative learning, I can freely choose the content I want to see and share. | (McMillan & Hwang, 2002) |

| PI2 | When using social media for cooperative learning, I can control what I do. | |

| PI3 | I believe that I have a high degree of control over my social media usage experience | |

| PI4 | I share my experiences and feelings with my peers through social media. | |

| PI5 | I can benefit from my peers using the same social media platform. | |

| PI6 | I have common expectations with my peers using the same social media platform. | |

| PI7 | When using social media for cooperative learning, my peers pay great attention to the information I post. | |

| PI8 | I always hope that my messages will receive many replies. | |

| PI9 | I always hope that my messages will be replied quickly. | |

| Cooperative learning attitudes based on social media, SM | ||

| ACLBS1 | Through group collaboration, my learning ability has been improved. | (McMillan & Hwang, 2002; Sarwar et al., 2019) |

| ACLBS2 | I can acquire new knowledge and skills from other members on social media. | |

| ACLBS3 | Through group collaboration, I have a more comprehensive understanding of the learning topic. | |

| Knowledge Sharing Willingness, KSW | ||

| WSK1 | My knowledge sharing with team members is poor. | (Bock et al., 2005) |

| WSK2 | My knowledge sharing experiences with team members are pleasant. | |

| WSK3 | I think it is a wise choice to share knowledge with team members. | |

| WSK4 | In the future, I will share cooperative reports and learning files more frequently with team members. | |

| WSK5 | I always inform team members where to obtain knowledge or who can answer their questions according to their needs. | |

| Academic Self-Efficacy, ASE | ||

| ASE1 | I have no doubt that I am in a position to complete the tasks in cooperative learning excellently | (Molinillo et al., 2018) |

| ASE2 | I expect to achieve good results in group cooperative learning. | |

| ASE3 | I am sure that I can master the skills required in group cooperative assignments. | |

| ASE4 | I am confident that I can understand the most complex content that the teacher requires to be completed in group cooperation. | |

| ASE5 | I believe that I will achieve excellent results in cooperative assignments. | |

| Learning Performance, LP | ||

| LP1 | I feel that I have the ability to complete my academic tasks. | (Ainin et al., 2015; Sarwar et al., 2019) |

| LP2 | I have learned how to complete cooperative tasks efficiently. | |

| LP3 | My academic performance is as good as I expected. | |

References

- Ainin, S., Naqshbandi, M. M., Moghavvemi, S., & Jaafar, N. I. (2015). Facebook usage, socialization and academic performance. Computers & Education, 83, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçayır, G., & Akçayır, M. (2016). Research trends in social network sites’ educational use: A review of publications in all SSCI journals to 2015. Review of Education, 4(3), 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A. A. (2018). Investigating the impact of social media advertising features on customer purchase intention. International Journal of Information Management, 42(1), 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazy, W. M., Mugahed Al-Rahmi, W., & Khan, M. S. (2019). Validation of TAM model on social media use for cooperative learning to enhance cooperative authoring. IEEE Access, 7, 71550–71562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhathlan, A. A., & Al-Daraiseh, A. A. (2017). An analytical study of the use of social networks for cooperative learning in higher education. International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science, 9(2), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almogren, A. S. (2023). Art students’ interaction and engagement: The mediating roles of cooperative learning and actual use of social media affect academic performance. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 14423–14451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qawasmi, J. (2005). Digital media in architectural design education: Reflections on the e-studio pedagogy. Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 4(3), 205–222. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rahmi, W. M., Alias, N., Othman, M. S., Marin, V. I., & Tur, G. (2018). A model of factors affecting learning performance through the use of social media in Malaysian higher education. Computers & Education, 121, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rahmi, W. M., Yahaya, N., Alturki, U., Alrobai, A., Aldraiweesh, A. A., Omar Alsayed, A., & Kamin, Y. B. (2020). Social media-based cooperative learning: The effect on learning success with the moderating role of cyberstalking and cyberbullying. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(8), 1434–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardichvili, A., Maurer, M., Li, W., Wentling, T., & Stuedemann, R. (2006). Cultural influences on knowledge sharing through online communities of practice. Journal of Knowledge Management, 10(1), 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augsten, A., & Gekeler, M. (2017). From a master of crafts to a facilitator of innovation. how the increasing importance of creative collaboration requires new ways of teaching design. The Design Journal, 20(Suppl. 1), S1058–S1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, V. (2017). Key determinants for intention to use social media for learning in higher education institutions. Universal Access in the Information Society, 16, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Editorial. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, K., Shivakumar, S., & Kumar, T. (2021). Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need (information policy) by Sasha Costanza-Chock. Design Issues, 37(4), 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G. W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y. G., & Lee, J. N. (2005). Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozanta, A., & Mardikyan, S. (2017). The effects of social media use on cooperative learning: A case of Turkey. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 18, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. H., & Chuang, S.-S. (2011). Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Information & Management, 48(1), 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-S., Chuang, Y.-W., & Chen, P.-Y. (2012). Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of KMS quality, KMS self-efficacy, and organizational climate. Knowledge-Based Systems, 31, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1985). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results [Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology]. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1992). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22(14), 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearing, E., & Hamilton, L. C. (2006). Contemporary advances and classic advice for analyzing mediating and moderating variables. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 71(3), 88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouil, M. (2015). Human-centered design projects and co-design in/outside the Turkish classroom: Responses and challenges. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 34(3), 358–368. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.-L., Wu, Y.-L., & Ho, H.-C. (2009). An investigation of coopetitive pedagogic design for knowledge creation in web-based learning. Computers & Education, 53, 550–562. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, M., Xu, Y., & Yu, Y. (2004). An enhanced technology acceptance model for web-based learning. Journal of Information Systems Education, 15(4), 365–374. [Google Scholar]

- Güldal, H., & Dinçer, E. O. (2025). Can rule-based educational chatbots be an acceptable alternative for students in higher education? Education and Information Technologies, 30, 3979–4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, S., Waycott, J., Chang, S., & Kurnia, S. (2011). Appropriating online social networking (OSN) activities for higher education: Two Malaysian cases. In Changing demands, changing directions proceedings ascilite Hobart (pp. 526–538). University of Tasmania. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, H., Ma, L., Wang, D., & Qu, L. (2024). Untangling the influence of data literacy and knowledge sharing willingness on academic achievement of college students in China: A moderated mediation model. Asia Pacific Education Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F., & Liu, S. Y. (2024). If I enjoy, I continue: The mediating effects of perceived usefulness and perceived enjoyment in the continuance of asynchronous online English learning. Education Sciences, 14(8), 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C., Rashid, R. M., & Wang, J. (2019). Investigating the role of social presence dimensions and information support on consumers’ trust and shopping intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junco, R. (2012). Too much face and not enough books: The relationship between multiple indices of Facebook use and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, S., Amin, F., Masoodi, N., & Khan, M. F. (2023). Factors influencing online learning on social media. International Journal of Learning Technology, 18(1), 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, Ö. (2012). A validity and reliability study of the Online Cooperative Learning Attitude Scale (OCLAS). Computers & Education, 59(4), 1162–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz, Ö., & Yesil, R. (2011). Evaluation of achievement, attitudes towards technology using and opinions about group work among students working in gender based groups. Gazi University Journal of Gazi Education Faculty, 31(1), 201–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S. J., Park, E., & Kim, K. J. (2014). What drives successful social networking services? A comparative analysis of user acceptance of Facebook and Twitter. The Social Science Journal, 51(4), 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W. W. S., & Yang, M. (2020). Effective collaborative learning from Chinese students’ perspective: A qualitative study in a teacher-training course. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(2), 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J., & Richardson, J. C. (2016). Exploring the effects of students’ social networking experience on social presence and perceptions of using SNSs for educational purposes. The Internet and Higher Education, 29, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L. (2017). Cultural flows and pedagogical dilemmas: Teaching with collaborative learning in the Chinese HE EFL context. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 40(1), 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Zaigham, G. H. K., Rashid, R. M., & Bilal, A. (2022). Social media-based cooperative learning effects on student performance/learner performance with moderating role of academic self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 903919. [Google Scholar]

- MacGeorge, E. L., Homan, S. R., Dunning, J. B., Jr., Elmore, D., Bodie, G. D., & Evans, E. (2008). The influence of learning characteristics on evaluation of audience response technology. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 19, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J. (2014). Social media for learning: A mixed methods study on high school students’ technology affordances and perspectives. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, S. J., & Hwang, J.-S. (2002). Measures of perceived interactivity: An exploration of the role of direction of communication, user control, and time in shaping perceptions of interactivity. Journal of Advertising, 31(3), 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micari, M., & Drane, D. (2011). Intimidation in small learning groups: The roles of social-comparison concern, comfort, and individual characteristics in student academic outcomes. Active Learning in Higher Education, 12(3), 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S., Anaya-Sánchez, R., Aguilar-Illescas, R., & Vallespín-Arán, M. (2018). Social media-based cooperative learning: Exploring antecedents of attitude. The Internet and Higher Education, 38, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nand, S., Pitafi, A. H., Kanwal, S., Pitafi, A., & Rasheed, M. I. (2019). Understanding the academic learning of university students using smartphone: Evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Public Affairs, 20, e1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örnekoğlu-Selçuk, M., Emmanouil, M., Hasirci, D., Grizioti, M., & Van Langenhove, L. (2023). A systematic literature review on co-design education and preparing future designers for their role in co-design. CoDesign, 20(2), 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örnekoglu Selçuk, M., Emmanouil, M., Hasirci, D., Grizioti, M., & Van Langenhove, L. (2024). Preparing future designers for their role in co-design: Student insights on learning co-design. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 43(2), 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Paliktzoglou, V., & Suhonen, J. (2014). Facebook as an assisted learning tool in problem-based learning: The Bahrain case. International Journal of Social Media and Interactive Learning Environments, 2(1), 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitafi, A. H., Kanwal, S., Alii, A., Khan, A. N., & Ameen, W. (2018). Moderating roles of IT competency and work cooperation on employee work performance in an ESM environment. Technology in Society, 55, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, D. D., Mazanov, J., Meacheam, D., Heaslip, G., & Hanson, J. (2016). Attitude, digital literacy and self efficacy: Flow-on effects for online learning behavior. The Internet and Higher Education, 29, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M. I., Malik, J., Pitafi, A. H., Iqbal, J., Anser, M. K., & Abbas, M. (2020). Usage of social media and student engagement and creativity: The role of knowledge sharing behavior and cyberbullying. Computers & Education, 159, 104002. [Google Scholar]

- Rasto, R., Muhidin, S. A., Inayati, T., & Marsofiyati, M. (2021). University student’s experiences with online synchronous learning during COVID-19. Jurnal Pendidikan Ekonomi Dan Bisnis (JPEB), 9, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauniar, R., Rawski, G., Johnson, B., & Yang, J. (2013). Social media user satisfaction-theory development and research findings. Journal of Internet Commerce, 12(2), 195–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauniar, R., Rawski, G., Yang, J., & Johnson, B. (2014). Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and social media usage: An empirical study on Facebook. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 27(1), 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, M. S., Saleh, N. S., Md. Ali, A., Abu Bakar, S., & Mohd Tahir, L. (2022). A systematic review of the technology acceptance model for the sustainability of higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic and identified research gaps. Sustainability, 14(18), 11389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, N., & Oleksiyenko, A. (2022). Chinese students collaborating across cultures. Academic Praxis, 2, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, B., Zulfiqar, S., Aziz, S., & Ejaz Chandia, K. (2019). Usage of social media tools for cooperative learning: The Effect on learning success with the moderating role of cyberbullying. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(1), 246–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sclater, M. (2016). Beneath our eyes: An exploration of the relationship between technology enhanced learning and socio-ecological sustainability in art and design higher education. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 35(3), 296–306. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E. E. (2016). “A real double-edged sword”: Undergraduate perceptions of social media in their learning. Computers & Education, 103, 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.-C., & Wang, T.-H. (2025). What is the role of learning style preferences on the STEM learning attitudes among high school students? International Journal of Educational Research, 129, 102488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. (2021). Classroom culture in China: Collective individualism learning model, by X. Zhu and J. Li, Singapore, Springer, 2020, xv + 122 pp., £89.99 (hbk), ISBN: 9789811518263, £71.50 (eBook), ISBN: 9789811518270. Language and Education, 36(1), 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q., & Sundar, S. S. (2016). Interactivity and memory: Information processing of interactive versus non-interactive content. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., van Lieshout, L. L. F., Colizoli, O., Li, H., Yang, T., Liu, C., Qin, S., & Bekkering, H. (2025). A cross-cultural comparison of intrinsic and extrinsic motivational drives for learning. Cognitive Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 25, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L., & Lu, Y. (2012). Enhancing perceived interactivity through network externalities: An empirical study on micro-blogging service satisfaction and continuance intention. Decision Support Systems, 53(4), 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L., & Huang, R. (2016). The effects of sentiments and co-regulation on group performance in computer supported cooperative learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 28, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., & Long, L. (2004). Statistical remedies for common method biases. Advances in Psychological Science, 12, 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z., & Li, J. (2019). Investigating ‘collective individualism model of learning’: From Chinese context of classroom culture. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(3), 270–283. [Google Scholar]

| Items | Number | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 114 | 37.38 |

| Female | 191 | 62.62 | |

| Age | 18 years and younger | 7 | 2.30 |

| 18–25 years old | 286 | 93.77 | |

| 26–35 years old | 12 | 3.93 | |

| Current stage of education | Undergraduate | 205 | 67.21 |

| Postgraduate or above | 100 | 32.79 |

| Construct | Item | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived usefulness | PU1 | 0.754 | 0.78 | 0.550 | 0.782 |

| PU2 | 0.761 | ||||

| PU3 | 0.698 | ||||

| Perceived ease of use | PEU1 | 0.620 | 0.80 | 0.591 | 0.810 |

| PEU2 | 0.854 | ||||

| PEU3 | 0.812 | ||||

| Perceived enjoyment | PE1 | 0.852 | 0.88 | 0.708 | 0.879 |

| PE2 | 0.825 | ||||

| PE3 | 0.847 | ||||

| Perceptual interactivity | PI1 | 0.786 | 0.92 | 0.582 | 0.926 |

| PI2 | 0.739 | ||||

| PI3 | 0.754 | ||||

| PI4 | 0.746 | ||||

| PI5 | 0.703 | ||||

| PI6 | 0.721 | ||||

| PI7 | 0.759 | ||||

| PI8 | 0.754 | ||||

| PI9 | 0.891 | ||||

| Attitude towards cooperative learning based on social media | ACLBS1 | 0.743 | 0.76 | 0.530 | 0.771 |

| ACLBS2 | 0.693 | ||||

| ACLBS3 | 0.746 | ||||

| Learning performance | LP1 | 0.862 | 0.85 | 0.655 | 0.850 |

| LP2 | 0.759 | ||||

| LP3 | 0.804 | ||||

| Academic self-efficacy | ASE1 | 0.848 | 0.92 | 0.703 | 0.922 |

| ASE2 | 0.827 | ||||

| ASE3 | 0.854 | ||||

| ASE4 | 0.786 | ||||

| ASE5 | 0.873 | ||||

| Willingness to share knowledge | WSK1 | 0.850 | 0.92 | 0.710 | 0.924 |

| WSK2 | 0.804 | ||||

| WSK3 | 0.791 | ||||

| WSK4 | 0.870 | ||||

| WSK5 | 0.893 |

| PU | PEU | PE | PI | ACLBS | LP | ASE | WSK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PU | 0.738 | |||||||

| 2. PEU | 0.117 | 0.769 | ||||||

| 3. PE | 0.333 | 0.558 | 0.769 | |||||

| 4. PI | 0.020 | 0.413 | 0.483 | 0.763 | ||||

| 5. CLABS | 0.387 | 0.516 | 0.578 | 0.428 | 0.728 | |||

| 6. LP | 0.155 | 0.267 | 0.217 | 0.331 | 0.347 | 0.809 | ||

| 7. ASE | 0.118 | 0.008 | 0.046 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.838 | |

| 8. KSW | 0.138 | 0.108 | 0.048 | 0.078 | 0.029 | 0.014 | 0.238 | 0.842 |

| Hypothesis (n = 305) | Unstd. | S.E. | C.R. | p | Std | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 PU→ACLBS | 0.254 | 0.064 | 3.949 | <0.001 *** | 0.278 | Supported |

| H2 PEU→ACLBS | 0.216 | 0.061 | 3.554 | <0.001 *** | 0.276 | Supported |

| H3 PE→ACLBS | 0.17 | 0.064 | 2.669 | 0.008 ** | 0.229 | Supported |

| H4 PI→ACLBS | 0.186 | 0.058 | 3.202 | 0.001 ** | 0.218 | Supported |

| H5 ACLBS→LP | 0.532 | 0.099 | 5.37 | <0.001 *** | 0.378 | Supported |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t | b | SE | t | b | SE | t | |

| Constant | 2.881 | 0.048 | 59.895 ** | 2.881 | 0.048 | 59.796 ** | 2.874 | 0.043 | 66.856 ** |

| ACLBS | 0.328 | 0.064 | 5.141 ** | 0.328 | 0.064 | 5.132 ** | 0.354 | 0.057 | 6.200 ** |

| WSK | −0.001 | 0.056 | −0.024 | −0.007 | 0.050 | −0.143 | |||

| ACLBS × WSK | 0.567 | 0.064 | 8.864 ** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.080 | 0.080 | 0.271 | ||||||

| F | 26.426 | 13.170 | 37.226 | ||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t | b | SE | t | b | SE | t | |

| Constant | 2.881 | 0.048 | 59.895 ** | 2.881 | 0.048 | 59.796 ** | 2.881 | 0.045 | 63.467 ** |

| SM | 0.328 | 0.064 | 5.141 ** | 0.328 | 0.064 | 5.140 ** | 0.352 | 0.060 | 5.837 ** |

| ASE | 0.054 | 0.060 | 0.902 | 0.054 | 0.057 | 0.947 | |||

| ACLBS × ASE | 0.512 | 0.083 | 6.185 ** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.080 | 0.080 | 0.271 | ||||||

| F | 26.426 | 13.612 | 22.944 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, T.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y. Drivers and Moderators of Social Media-Enabled Cooperative Learning in Design Education: An Extended TAM Perspective from Chinese Students. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070886

Xia T, Wu Y, Chen Y. Drivers and Moderators of Social Media-Enabled Cooperative Learning in Design Education: An Extended TAM Perspective from Chinese Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):886. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070886

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Tiansheng, Yujiao Wu, and Yibing Chen. 2025. "Drivers and Moderators of Social Media-Enabled Cooperative Learning in Design Education: An Extended TAM Perspective from Chinese Students" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070886

APA StyleXia, T., Wu, Y., & Chen, Y. (2025). Drivers and Moderators of Social Media-Enabled Cooperative Learning in Design Education: An Extended TAM Perspective from Chinese Students. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070886