1. Introduction

The rise of shadow education has generated widespread attention and debate. In pursuit of improved academic performance, parents of adolescent students frequently enroll their children in professional tutoring institutions and extracurricular coaching classes after school (

J. Luo & Chan, 2022). This pattern is especially common among parents who value academic success and can afford tutoring, yet lack the time or expertise to help their children directly. Shadow education—referring to educational activities conducted outside formal schooling—has expanded rapidly across various countries in recent years (

Bray, 2024). Its growth and diffusion are driven by complex social dynamics at both the individual and group levels.

At the individual level, fierce competition for scarce educational opportunities pushes families to pursue admission to elite universities—gateways to better careers, higher incomes, and greater social standing. Access to renowned universities often requires success in rigorous examinations or contests, which families perceive as highly demanding academic benchmarks. Shadow education is thus viewed as a strategic tool to help adolescents gain an edge in these competitive processes. Parents expect shadow education to help their children outpace peers and climb the educational and social ladder (

S. Li, 2023;

J. Luo & Chan, 2022).

At the group level, peer and societal pressures further reinforce the prevalence of shadow education. In East Asian contexts, where academic success is highly valued, the widespread use of shadow education creates a competitive dynamic that compels other families to participate. The visibility of students gaining advantages through supplementary educational activities amplifies fears of falling behind, exacerbating competitive anxiety among remaining families (

Kim et al., 2022;

Pan et al., 2022;

Ren et al., 2024).

As shadow education becomes an increasingly pervasive social phenomenon, its implications for educational equity and social development have prompted extensive debate. Supporters argue that shadow education fills the gaps left by classroom instruction, providing personalized and flexible learning that can boost societal human capital (

Guo et al., 2020;

Zheng et al., 2020). However, critics raise several concerns. First, shadow education does not consistently demonstrate clear advantages over traditional classroom instruction and may not always lead to improved academic outcomes (

Guill et al., 2020;

Zhao, 2015). Second, it carries the risk of inefficient resource allocation and the exacerbation of social inequalities. Substantial societal investment in shadow education may divert resources from the formal education system, potentially undermining the quality of classroom teaching. For example, skilled educators may be drawn away from formal education to the shadow education sector due to higher financial incentives, leading to a misallocation of educational talent. Furthermore, shadow education often involves higher costs and greater entry barriers than inclusive formal education, making it more accessible to privileged groups while marginalizing disadvantaged populations (

Jansen et al., 2023;

W. Zhang & Bray, 2018). Even in contexts with strict regulatory oversight, shadow education can exacerbate inequalities through rent-seeking behavior, influencing how educational resources are distributed (

J. Li et al., 2024). Consequently, shadow education may reproduce social inequality and undermine efforts to equalize opportunity within formal schooling.

When evaluating the consequences of shadow education, it is essential to consider its potential impact on mental health. Adolescence is a pivotal stage for mental health because rapid physical, emotional, and social changes heighten exposure to stressors. At the same time, the social and emotional mechanisms for coping with stress are not yet fully developed in adolescents, rendering them more vulnerable to psychological pressures (

Codjoe et al., 2024;

Marthoenis & Schouler-Ocak, 2022). From a life-course perspective, many mental health problems first emerge during adolescence, with a significant proportion persisting into adulthood (

Kessler et al., 2005). Adolescent mental health has, therefore, become a global concern, particularly as prevalence rates of mental health issues continue to rise worldwide. Moreover, many adolescents in low-income and middle-income countries lack timely or professional mental health care (

Mudunna et al., 2025a;

Twenge et al., 2021), amplifying harms to individuals and society.

Research on the determinants of adolescent mental health emphasizes the interaction between individual and environmental factors. Family migration, school victimization, and gender norms all shape adolescent mental health outcomes (

Cheung, 2020;

Putra et al., 2022;

Xu & Ren, 2025). In the field of educational psychology, education, as both a developmental process and a social environment, plays a critical role in shaping adolescent mental health. Schooling involves not just learning content, but also ongoing interactions with peers and the broader social environment. For adolescents, education can introduce new stresses yet also offer avenues—through positive interventions—to relieve psychological pressure (

Garaigordobil, 2023;

X. Luo et al., 2022).

The expanding empirical literature links education and adolescent mental health, with some studies probing the causal mechanisms involved. Most research focuses on how various dimensions of the educational process relate to adolescent mental health—for example, a positive educational environment and active engagement in learning are identified as protective factors (

Chen et al., 2024;

Ford et al., 2021), whereas adverse school environments and poor peer relationships are recognized risk factors (

Mudunna et al., 2025b). Educational expansion and the move to a knowledge economy have intensified academic pressure on adolescents, potentially contributing to rising mental health problems worldwide (

Högberg, 2021). Despite ongoing debate, some studies emphasize the complexity of the relationship, calling for more rigorous examinations of causality in this area (

Leurent et al., 2021;

Steare et al., 2023). Advanced statistical techniques, such as randomized controlled trials and longitudinal analyses, provide stronger evidence for causal links between dimensions like academic stress, school relationships, engagement, and sense of belonging, and adolescent mental health outcomes (

Singla et al., 2021;

Steare et al., 2023). This complexity underscores the need for multidimensional approaches that evaluate both the academic benefits and potential psychological costs associated with shadow education.

Although shadow education can improve academic performance, its potential mental health costs warrant closer scrutiny. In the process of acquiring, producing, or maintaining something, individuals generally incur various forms of costs, most commonly in the form of money, labor, or time. However, challenges and burdens related to mental health can also constitute significant costs associated with specific behaviors and goals (

David, 2011;

Sahithya & Reddy, 2018). In this context, the mental health costs of shadow education refer to the psychological harm and burdens adolescents may experience while participating in shadow education in pursuit of academic success. Shadow education requires considerable time and financial investment from both adolescents and their families, and can also impact adolescents’ mental health status. As a significant form of education, shadow education is inherently connected to academic performance and directly influences the degree of academic stress experienced by students. Moreover, because shadow education operates outside the standardized boundaries of formal schooling, it often overlaps with leisure time, reducing opportunities for rest and relaxation, which may intensify psychological pressures (

Kuan, 2018;

D. Wang et al., 2022). In short, tutoring can simultaneously aggravate and alleviate stress, giving it a complex role in adolescent mental health. Consequently, participation in shadow education continuously shapes adolescent mental health, and students may incur lasting psychological costs in their pursuit of academic success.

Nevertheless, the complex causal relationship between shadow education and adolescent mental health has not been fully established. Accordingly, the discussion of mental health costs in this study is grounded in the association between shadow education and adolescent mental health, rather than definitive causality. Determining how much shadow education actually costs adolescents psychologically will require studies that use rigorous causal inference methods.

Despite increasing attention to the academic outcomes of shadow education, its effects on adolescents’ mental health remain insufficiently explored. Most existing studies focus on whether shadow education improves academic achievement or which groups of students benefit most academically (

Bray, 2014;

Hajar & Karakus, 2022). Only limited research has investigated the mental health implications, leaving significant gaps in understanding the conditions under which shadow education affects psychological well-being. Some scholars argue that shadow education not only enhances academic performance, but also serves as a coping strategy for adolescents and their parents to manage academic pressure and alleviate anxiety (

Sun et al., 2020). Conversely, critics highlight that, as an activity situated outside the official curriculum, shadow education inevitably encroaches upon adolescents’ leisure time, increases academic burdens, and introduces additional sources of psychological stress (

Hu & Mu, 2020).

Reaching a consensus on how shadow education affects adolescent mental health remains a complex issue. Further research is needed to clarify the conditions under which shadow education produces positive or negative mental health outcomes. This requires a nuanced examination of factors such as the duration of shadow education and the broader context in which it occurs, including family dynamics, educational policies, and societal environment.

China provides a compelling context for examining shadow education amid shifting regulatory landscapes. The development of shadow education practices varies considerably across countries, shaped by differing policy approaches and cultural priorities. Some nations, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, Singapore, Nigeria, and South Africa, have adopted laissez-faire or supportive policies, thereby fostering the growth of shadow education. In contrast, countries like Vietnam, South Korea, Myanmar, and Lithuania have imposed strict supervision or outright bans, actively regulating or restricting shadow education practices (

Silova et al., 2006, p. 14). In China, shadow education has undergone significant transformations, driven by cultural emphasis on academic success and evolving government policies. Before 2018, shadow education in China largely prospered under a laissez-faire approach. By 2020, the sector encompassed over 4 million training institutions and employed more than 11 million individuals. Shadow education not only operated alongside the formal education system, but, in some respects, surpassed it, raising concerns regarding educational equity and academic burden (

W. Zhang, 2023, p. 61). In response, the Chinese government introduced a series of regulatory interventions, culminating in the implementation of the “Double Reduction” Policy (“Shuang Jian Zhengce”) in 2021.

The “Double Reduction” Policy is a comprehensive educational reform launched by the Chinese central government, targeting adolescents at the compulsory education stage. Its title reflects two primary objectives, reducing both the excessive homework burden assigned by schools and the heavy reliance on private after-school tutoring. The policy emerged as a response to mounting public concerns over escalating academic pressure and educational inequities exacerbated by the expansion of shadow education. The rationale behind the “Double Reduction” Policy acknowledges that the flourishing private tutoring industry had become a major source of stress for families and students. To address these challenges, the policy introduced a series of concrete measures. First, it strictly regulates both the quantity and difficulty of school-assigned homework, such as prohibiting written homework for lower primary students and setting clear time limits for other grades. Second, it targets the for-profit tutoring industry by banning the provision of tutoring in core subjects on weekends, holidays, and school breaks, and requires all academic tutoring organizations serving compulsory education students to register as non-profit entities. Additionally, the policy enforces strict financial regulations, including bans on public listings and foreign investment in tutoring companies, to curb the commodification of education.

The effects of these regulatory reforms have been significant, as evidenced by a sharp decline in the number of officially registered shadow education institutions and employees, effectively curbing the sector’s rapid expansion. Nevertheless, shadow education has not disappeared entirely from Chinese society. Instead, educational providers have adapted by rebranding services and modifying instructional methods, effectively bypassing some of the policy restrictions while continuing to meet persistent demand. Empirical studies from China indicate that, following the introduction of the Double Reduction Policy, the time and financial investment adolescents devote to shadow education have generally declined. However, the policy’s impact varies across socioeconomic groups, with middle-income families experiencing the most significant changes, while high-income and low-income groups remain less affected (

Pang et al., 2025).

These dynamics make China a compelling case for examining the mental health implications of shadow education. On the one hand, the phenomenon is deeply embedded in China’s social and cultural fabric, reflecting the high value placed on education in East Asian societies and intense competition for educational resources. Shadow education, therefore, shapes not only academic outcomes, but also the mental well-being of Chinese adolescents. On the other hand, the mental health consequences of shadow education are closely linked to social context. The evolving regulatory environment in China provides a unique opportunity to investigate how changes in policy influence the relationship between shadow education and adolescent mental health. Differences in family background and parental decisions, shaped by shifting regulations, are likely to modulate shadow education’s mental-health effects.

To better understand the mental health consequences of shadow education, this study utilizes four large-scale survey datasets from China spanning 2016–2022. Within this framework, the duration of shadow education is examined, with depressive symptoms serving as indicators of mental health. The study analyzes how shadow education duration is associated with adolescents’ depressive symptoms, as well as the influence of social and contextual factors across different family backgrounds and regulatory environments.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Source

The data for this study are drawn from the China Family Panel Study (CFPS), a nationally representative and comprehensive social survey designed to collect data at the individual, family, and community levels. The CFPS tracks changes in China’s social, economic, demographic, educational, and health landscape. Initiated by a research team at Peking University in 2010, the CFPS conducts surveys from every one to two years, with the latest publicly available wave fielded in 2022.

The CFPS sample covers 25 provinces in China, representing approximately 95% of the total population. The survey employs a three-stage, implicitly stratified, probability sampling design. The primary sampling units (PSUs) are administrative districts or counties, the secondary sampling units (SSUs) are administrative villages or neighborhood committees, and the tertiary sampling units (TSUs) are households. Official administrative-division data guide the first two stages, and a map address method is used to construct the household frame in the third stage. Trained interviewers then conduct face-to-face computer-assisted interviews in respondents’ homes.

This study draws on data from the 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2022 CFPS waves for three reasons. First, a longer observation window facilitates a more comprehensive analysis of trends in adolescent depression and shadow education. Second, the selected period encompasses the year 2021, a critical point when the Chinese government implemented substantial regulatory policies on shadow education, enabling the assessment of these policies’ impacts. Third, adolescent subsamples are often limited in large-scale social surveys. By pooling data from these years—each containing the core variables of interest—substantially increases the adolescent sample size and enhances statistical power.

The CFPS project is a human subjects research initiative. To ensure participant protection, the research team regularly submits ethical review or ongoing review applications to the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Peking University. Data collection was conducted only after receiving approval from the ethics review.

For the purposes of data analysis, the adolescent sample was restricted to those aged from 10 to 15, for two main reasons. First, individuals in this age range experience rapid physical and psychological development, along with a certain degree of cognitive and emotional maturity. Second, this age group is at a pivotal stage of academic development, faces considerable academic pressure, and represents a primary clientele for shadow education. After rigorous data cleaning, the final analytic sample comprised 7739 adolescents.

Out of the initial 8773 adolescent observations, 1034 cases were excluded due to missing information on variables relevant to this study. Given the relatively low percentage of missing data (11.79%), listwise deletion was employed. To assess potential bias from missing data, a three-level binary logistic regression model was used to predict missingness. The results indicate that lower body weight was associated with a higher likelihood of being missing, while all other variables—including key explanatory variables such as shadow education duration and family income—were not significantly associated with missingness. Thus, there is no empirical evidence that missing data would substantially bias the study’s main results.

3.2. Variables

The dependent variable in this study is the level of depression, measured with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) developed by Radloff (

Radloff, 1977). Respondents are asked to self-report the frequency of depressive symptoms experienced over the past week, with four response options: Rarely, Sometimes, Often, and Most of the time. The CES-D comprises 20 items, including statements such as “I worry about small things,” “I feel lonely,” “I think others dislike me,” and “I find it hard to do anything.” Responses are summed to generate a continuous total depression score, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms and poorer mental health.

There are numerous instruments available for measuring depression, such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), among others (

Amtmann et al., 2014;

Jiang et al., 2019). The selection of the CES-D for this study is based on two considerations. First, the CES-D is widely used across diverse research populations and topics, demonstrating high internal consistency and test–retest reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients typically ranging from 0.85 to 0.90 (

Miller et al., 2008). Its discriminative validity for mental health has been consistently supported across different studies and regions, including China (

M. Wang et al., 2013). Second, although the CES-D is not intended for clinical diagnosis, it is highly sensitive to subclinical depressive symptoms in community and non-clinical populations, making it particularly suitable for large-scale epidemiological surveys. Given the objectives of this study, the CES-D is able to capture a wide spectrum of depressive symptoms among adolescents and provides a stable reference for mental health comparisons across different years.

The independent variables include three components. The first independent variable is the duration of shadow education. This is calculated by summing the time respondents spend each week participating in five types of shadow education activities, including tutoring, competition preparation, and cognitive development. The total time spent on shadow education each week is represented as a continuous variable.

The second independent variable is family income, which is measured by the per capita annual income of respondents’ households. Given that income may be skewed, a logarithmic transformation is applied to adjust for this distribution, resulting in a continuous variable that represents family income.

The third independent variable is the survey year. The original time points are adjusted to reflect three periods: before 2018, 2020, and 2022. This adjustment serves two purposes: first, to capture the potential impact of changes in China’s shadow education regulatory policies around 2021 on shadow education and mental health; and second, to account for the global pandemic in 2020, which may have caused abrupt changes in mental health due to external environmental factors, necessitating a distinction in the analysis.

Additionally, control variables were established across three levels: individual, family, and community. This approach is based on two primary considerations. First, the extant literature on the determinants of shadow education and mental health consistently emphasizes the importance of both individual-level and group-level factors, necessitating their simultaneous inclusion in the analysis. Second, the multi-level sampling design of the CFPS dataset enables the use of multi-level regression models to robustly control for variables across individual, family, and community levels.

Specifically, individual-level control variables include age, gender, years of education, height, weight, physical health, academic performance, incidence of absenteeism, class leadership position, and internet usage. Family-level variables include whether the adolescent is a left-behind child and the frequency of arguments with parents, both of which capture family environment influences. Community-level variables include the proportion of left-behind children in the community and the average academic performance of children in the community, which primarily control for the effects of community environment and peer pressure. To mitigate potential multicollinearity, all family-level and community-level control variables were mean-centered prior to analysis.

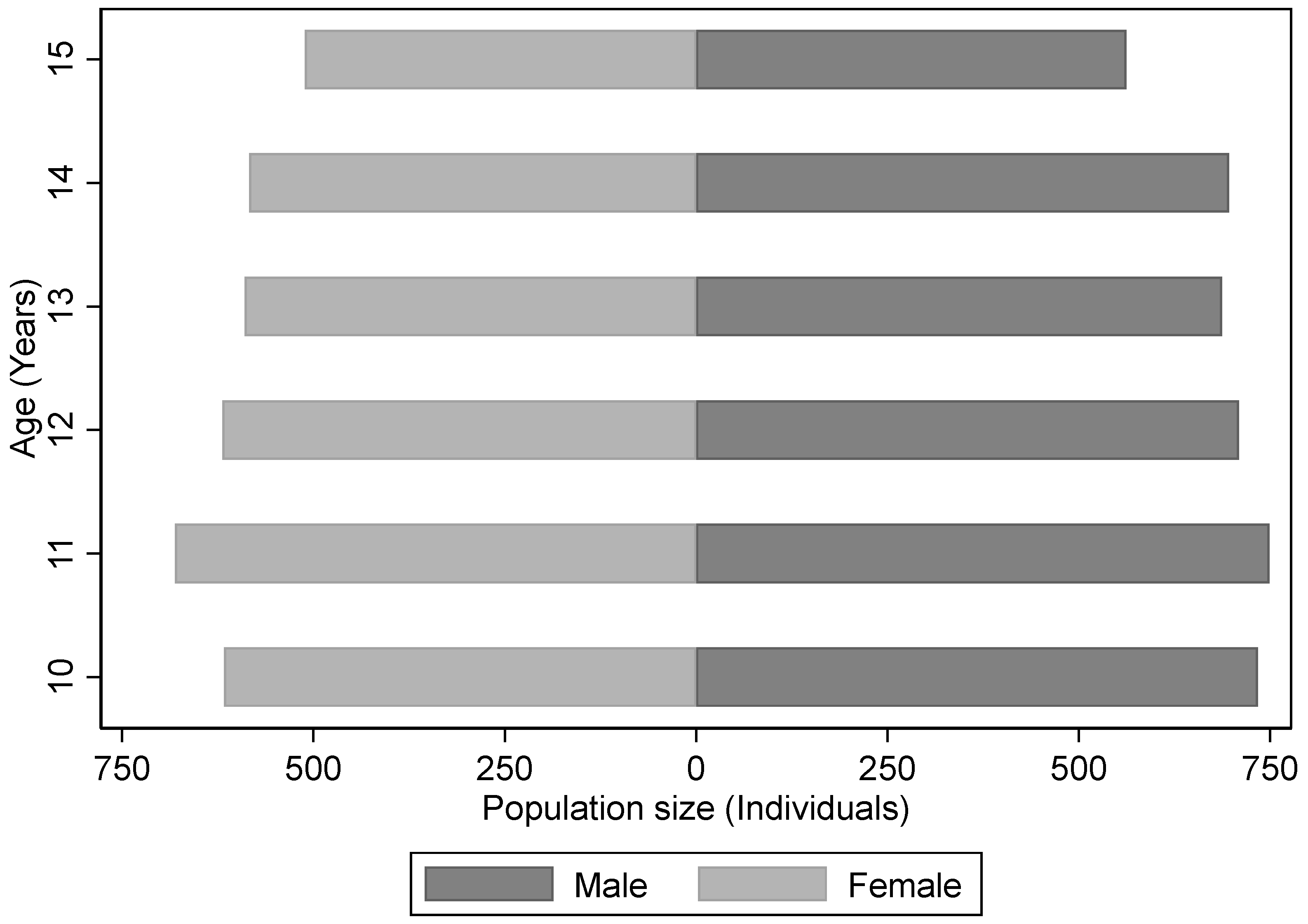

To present the basic demographic characteristics of the analytical sample, a population pyramid depicting the distribution of age and gender was plotted, as shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows that, among adolescents aged from 10 to 15, the gender distribution remains generally balanced—although males outnumber females at each age, a pattern consistent with overall population census data in China. In terms of age distribution, the largest number of adolescents are at age 11, while the smallest group is at age 15. However, the difference between these groups is relatively minor, indicating a fairly even distribution across ages. These patterns suggest that the analytical sample is broadly representative of the adolescent population in Chinese society.

The descriptive statistics for the other key variables are presented in

Table 1.

The descriptive results reveal two noteworthy initial findings. First, adolescent depression emerges as a prominent concern. The mean CES-D score exceeds 30, indicating that a substantial proportion of adolescents may be experiencing clinically relevant depressive symptoms. Second, shadow education participation varies widely across adolescents. While the average is approximately 3 h per week, the standard deviation is about 8 h, and the maximum value is as high as 100 h. This dispersion indicates that adolescents and their families make markedly different choices regarding shadow education participation, potentially leading to divergent outcomes.

3.3. Analytical Approach

Data analysis was conducted in four steps.

The first step involved a descriptive analysis to examine provides a descriptive overview of the annual changes in adolescent depression and shadow education in China.

The second step established a multi-level linear regression model encompassing individual, family, and community levels to examine how the duration of shadow education, family income, and survey year influence the level of depression among adolescents. This analysis aimed to evaluate whether the duration of shadow education exerts a nonlinear effect on adolescent mental health, as well as assess whether higher family income and the implementation of the “Double Reduction” policy contribute to improved mental health outcomes for adolescents.

In the third step, shadow education was categorized into three types: insufficient education, appropriate education, and excessive education. A multi-level binary logistic regression model, incorporating individual, family, and community levels, was employed to examine the impact of family income and survey year on these categories of shadow education. This analysis sought to determine tests whether higher family income and the implementation of the “Double Reduction” policy can help adolescents and their families make more reasonable decisions regarding the duration of shadow education encourage more judicious choices about shadow-education duration.

The fourth step adopted implemented three approaches to enhance robustness. First, an inverse probability weighted regression adjustment (IPWRA) model was used to control for adjusts for the confounding effects of various variables on the relationships among shadow education duration, family income, and survey year. Second, a multi-level multilevel linear regression analysis, incorporating individual, family, and community levels, was performed on subsamples with different levels of participation in shadow education to account for potential interference caused by bias introduced by COVID-19. Third, a series of sensitivity analyses based on Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) models was conducted to examine whether evaluate whether the estimated effects of shadow education duration on mental health are robust to potential biases from unobserved confounders.

All data analyses were performed using STATA software 18.0.

4. Results

4.1. Annual Changes in Depression Levels and Duration of Shadow Education

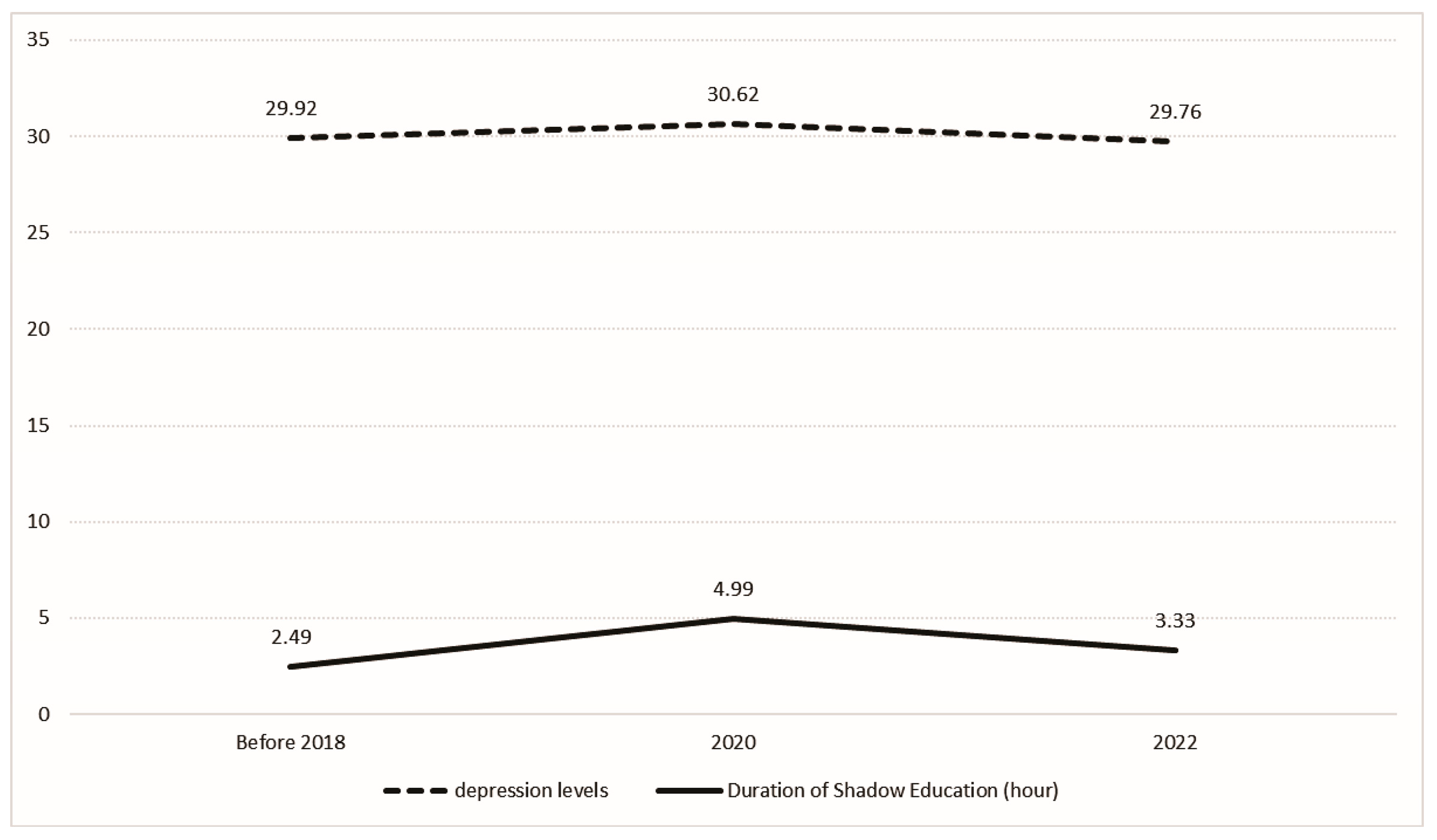

We organized the data by survey year to calculate the mean levels of depression and the average duration of shadow education among adolescents. The annual trends are displayed in

Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows that both depression levels and the duration of shadow education exhibited an initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease. Prior to 2018, both indicators remained relatively low. In 2020, there was a marked uptick in both the duration of shadow education and depression levels. By 2022, however, both measures experienced a significant decline.

Three preliminary observations emerge from these patterns. Three preliminary findings emerge from these results. First, fluctuations in shadow education hours track closely with changes in depression, suggesting a potential association between the two variables. Second, the 2021 “Double Reduction” reforms may have curtailed participation, a shift that appears to coincide with the decline in depression. Third, COVID-19 likely contributed to the 2020 surge—average shadow education hours roughly doubled relative to 2018—and although the pandemic persisted into 2022, participation fell substantially, plausibly reflecting the new policy environment. Nevertheless, these descriptive patterns require formal statistical testing to establish their validity.

4.2. Influence of Shadow Education Duration, Family Income, and Survey Year on Depression Levels

We next tested the study hypotheses using depression levels as the dependent variable; the results are summarized in

Table 2.

Model M1 serves as a null model, excluding all independent and control variables, with the primary purpose of evaluating whether a multi-level linear regression model is appropriate for analyzing adolescent depression levels. The results show that the likelihood ratio (LR) test indicates significant differences, suggesting that the multi-level linear regression model provides a better fit for the data compared to a standard linear regression model. Furthermore, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) at the family level is 0.220, while the ICC at the community level is 0.053. These findings underscore the substantial within-family and within-community homogeneity in adolescent depression levels, thus justifying the use of a multi-level linear regression approach.

Building upon the null model, Model M2 incorporates control variables, in addition to the duration of shadow education and its squared term, in order to investigate the potential nonlinear association between shadow education duration and depression levels.

Most control variables demonstrate statistically significant associations with depression levels. The results suggest that younger adolescents, males, individuals with more years of schooling, greater height, better physical health, higher academic performance, fewer school absences, those serving in leadership roles, non-left-behind children, individuals experiencing lower levels of parental conflict, and those residing in communities with lower proportions of left-behind adolescents tend to report lower levels of depression, indicating more favorable mental well-being.

By contrast, variables such as weight, internet usage, and the average academic performance of adolescents within the community do not reach statistical significance, suggesting their limited impact on depression levels. One possible explanation for the insignificance of weight is that its effect may be captured by the height variable. Additionally, the average academic performance of children within the community and the proportion of left-behind adolescents may exhibit multicollinearity, potentially obscuring each other’s effects. Moreover, given the widespread prevalence of internet use among contemporary adolescents, the effect of internet usage may be relatively uniform, contributing to minimal observed variation.

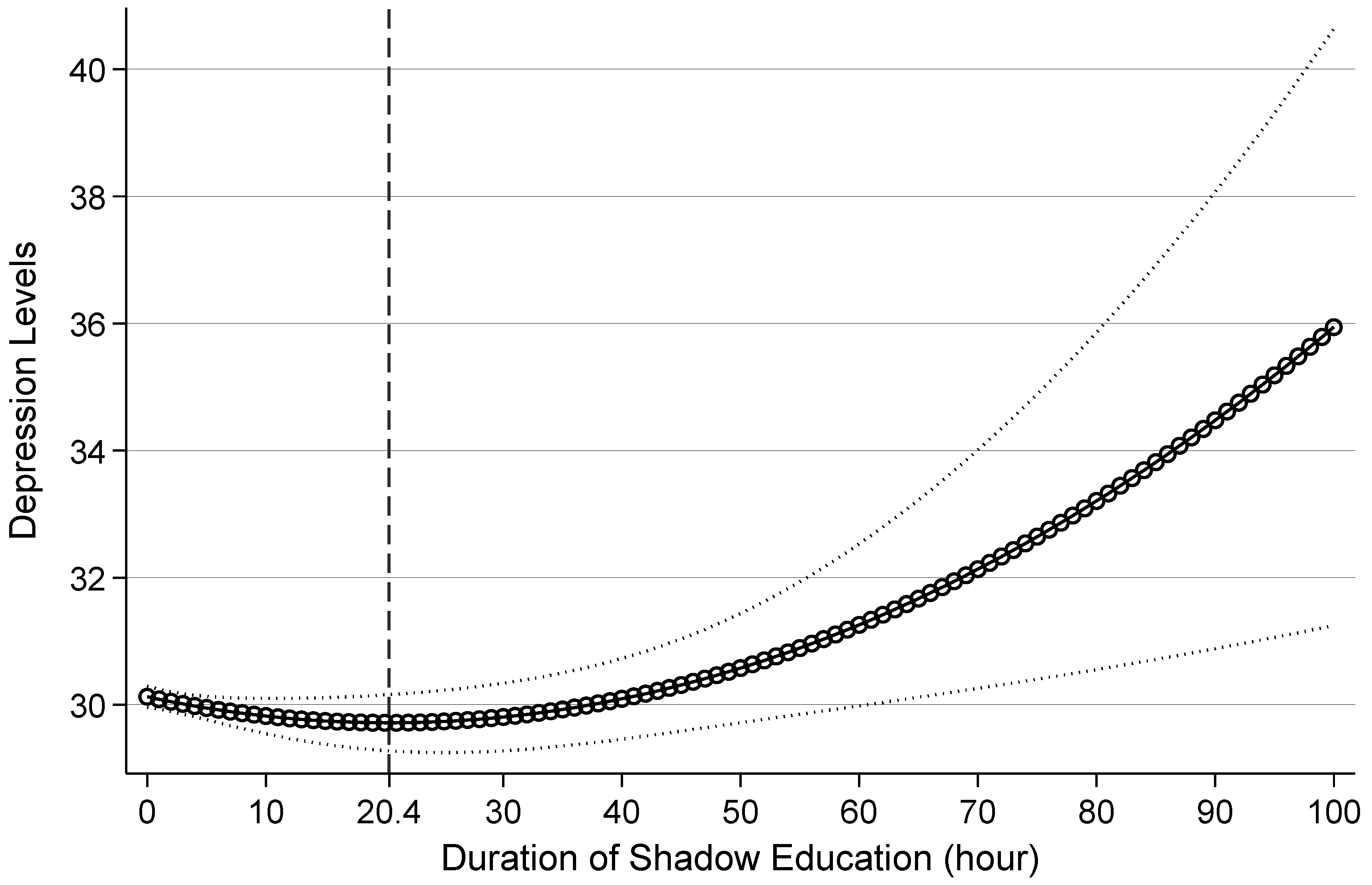

Regarding the independent variables, the results indicate a significantly negative coefficient for shadow education duration at the 0.05 level, while the coefficient for the squared term is significantly positive at the 0.01 level. These coefficients remained relatively stable across subsequent models, suggesting a potential nonlinear relationship between shadow education duration and depression levels. To visualize this pattern, the marginal effects of shadow education duration based on Model M4 are depicted in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 reveals a notable shift in the relationship between shadow education duration and adolescent depression levels at approximately 20.40 h per week. Specifically, when weekly shadow education hours range from 0 to 20.40, an increase in shadow education duration is associated with a continuous decrease in depression levels, suggesting an improvement in mental well-being. However, once the weekly duration surpasses 20.40 h, further increases are linked to rising depression levels, indicating a decline in mental health. Thus, the association between shadow education duration and adolescent depression exhibits a U-shaped pattern, while its relationship with mental health follows an inverted U-shaped curve. These results provide empirical support for Hypothesis H1.

In Model M3, family income is introduced to examine its potential association with adolescent depression. The results show that the coefficient for family income is −0.281 and statistically significant at the 0.01 level, a finding that remains consistent across subsequent models. This suggests that higher family income is associated with lower levels of adolescent depression and overall improved mental well-being. Therefore, the data supports Hypothesis H2.

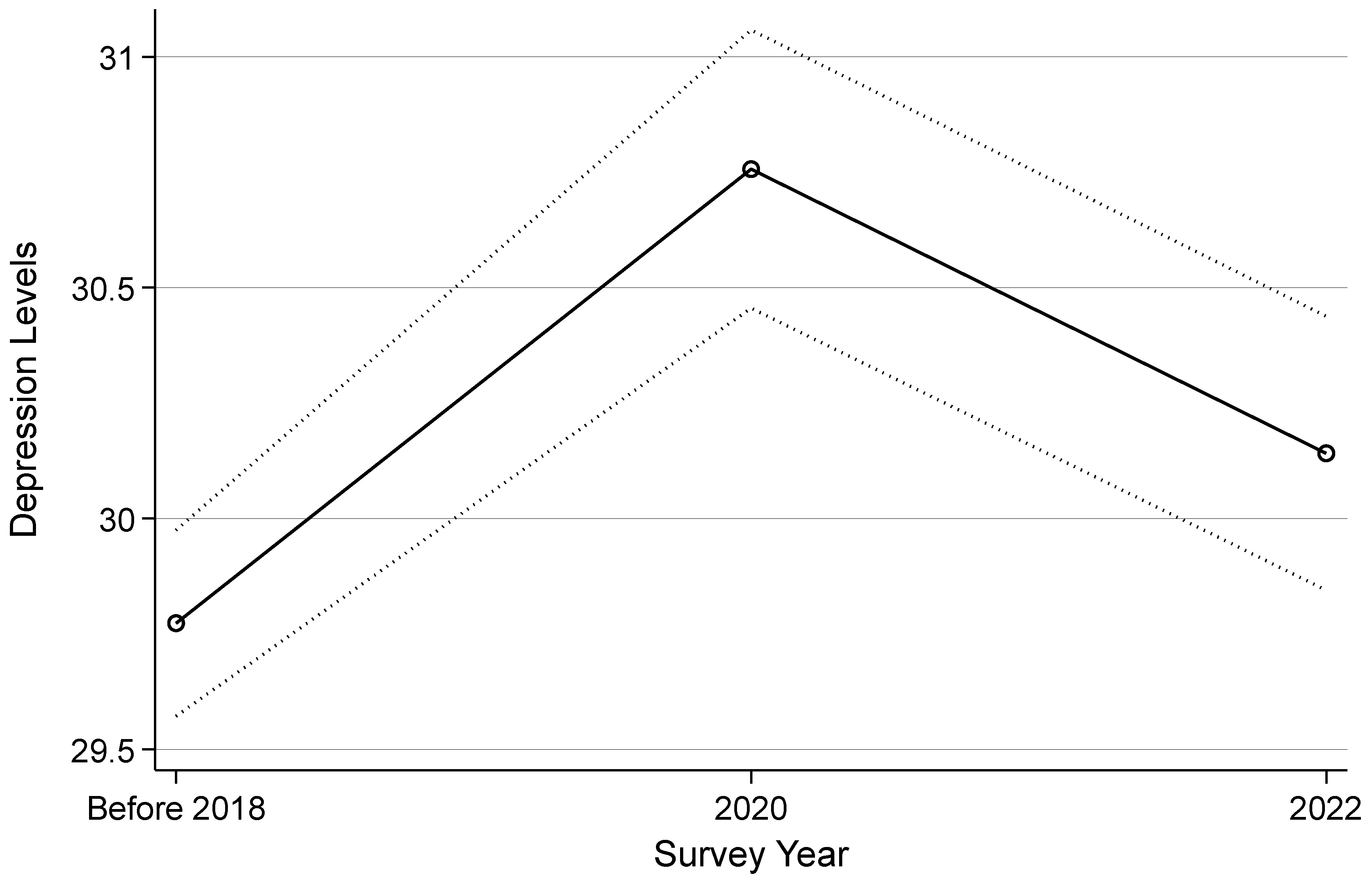

Model M4 further extends the analysis by incorporating the variable of survey year to assess potential changes in adolescent depression levels before and after 2021. Compared to the pre-2018 sample, the coefficients for the 2020 and 2022 samples are 0.983 and 0.368, respectively, reaching statistical significance at the 0.01 and 0.05 levels. To facilitate interpretation, a plot of the marginal effects based on Model M4 is presented in

Figure 4.

Figure 4 demonstrates that the association between survey year and depression levels is consistent with the earlier descriptive statistics, exhibiting a pattern of initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease. In the samples predating 2020, adolescent depression levels exhibited a continual rise, signaling a decline in mental well-being. However, in the 2022 sample, although depression levels among adolescents remained elevated compared to those before 2018, there was a noticeable decrease compared to the 2020 sample. This suggests that, post-2021, there has been an amelioration in adolescent depression levels. Thus, the data supports Hypothesis H3.

4.3. Influence of Family Income and Survey Year on Shadow Education Duration

Although the hypotheses are supported, it is still necessary to clarify why adolescents from higher-income families and those surveyed in 2022 exhibit mental health advantages. One plausible explanation, as previously discussed, is that family income and the implementation of the “Double Reduction” policy may encourage families to select a more appropriate duration of shadow education, thereby promoting better mental health outcomes.

To further investigate this issue, we analyzed the influence of family income and survey timing on the selection of an optimal duration of shadow education. Prior to this analysis, it was necessary to determine a reasonable threshold for shadow education duration. In Model M4, the data-validated inflection point was found to be 20.40 h, which closely aligns with our previously estimated threshold of 21 h per week, which was based on practical experience. Therefore, it is reasonable to set 21 h per week as the upper limit for a suitable shadow education duration, as this threshold has greater practical significance.

Based on the 21 h threshold, we categorized the data into three groups: insufficient education (0 h per week), appropriate education (0.1–21 h per week), and excessive education (more than 21 h per week). Since the current version of Stata does not support multilevel regression models for unordered multinomial dependent variables, we designated “appropriate education” as the reference group and constructed two binary outcome variables: appropriate education vs. insufficient education, and appropriate education vs. excessive education. We then employed a multilevel binary logistic regression model, incorporating individual, family, and community-level factors, to examine the effects of family income and survey year on the selection of an appropriate shadow education duration. The model successfully passed the null model test, and the likelihood ratio (LR) test indicated significant differences, suggesting that the multilevel binary logistic regression model is more suitable for this analysis than a standard binary logistic regression model. The results are presented in

Table 3.

Models M5 and M6 introduce the family income variable to examine how varying levels of family income are associated with the likelihood of selecting an appropriate duration of shadow education. The results from Model M5 indicate that individuals from wealthier families are 0.496 times likely to experience insufficient shadow education compared to those from less affluent backgrounds, with statistical significance at the 0.01 level. Similarly, Model M6 reveals that individuals from higher-income families are 0.774 times likely to engage in excessive shadow education than their lower-income counterparts, also significant at the 0.01 level. These findings suggest that adolescents from higher-income families are more likely to attain an appropriate duration of shadow education, supporting our earlier theoretical analysis.

Models M7 and M8 incorporate the survey year variable to assess how the selection of an appropriate shadow education duration among adolescents has changed before and after 2021. The results from Model M7 show that the odds of insufficient shadow education in the 2020 and 2022 samples are 0.648 and 0.766 times; both effects are statistically significant at the 0.01 level. In Model M8, the odds of excessive shadow education in the 2020 and 2022 samples are 1.935 times and 0.628 times, with statistical significance at the 0.01 and 0.05 levels.

These results should be interpreted in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The outbreak between 2018 and 2020 likely led more adolescents to participate in shadow education, an effect that persisted until 2023. Despite this increased participation during the pandemic, we did not observe a continuous rise or sustained high levels of shadow education duration. This suggests a relatively independent and distinct influence of the “Double Reduction” policy compared to the effects of the pandemic. In 2022, the likelihood of insufficient shadow education among adolescents slightly increased compared to 2020, although it remained significantly lower than in 2018. Conversely, the likelihood of excessive shadow education in 2022 significantly decreased compared to 2020. This indicates that the “Double Reduction” policy has generally guided adolescents and their families toward more reasonable decisions regarding shadow education, especially in reducing the prevalence of excessive shadow education. As a result, adolescent shadow education duration has reverted to a more appropriate range after 2021, which is consistent with our previous theoretical analysis.

4.4. Robustness Test

These findings should be interpreted in light of three key considerations.

First, duration of shadow education, family income, and survey timing may each be influenced by confounding factors. Because these characteristics are unevenly distributed in the population, variables such as age, gender, and years of education are simultaneously linked to participation in shadow education, family income, and survey timing, and are directly related to adolescent mental health. These variables are not randomly distributed within the population, indicating the presence of multiple confounders—such as age, gender, and years of education—which are associated with adolescents’ shadow education duration, family income, and survey timing, and also directly impact adolescents’ mental health. Although the analyses control for these factors as comprehensively as possible, residual selection bias may persist.

Second, the lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic must be disentangled from policy effects. Because the implementation of the “Double Reduction” reform coincided with the pandemic, distinguishing the policy signal from the pandemic signal requires multiple analytic strategies. The three-year duration of the pandemic has had widespread and enduring effects on various facets of public behavior and perceptions, which cannot be ignored. Notably, the implementation of the “Double Reduction” policy closely coincided with the pandemic, making it necessary to disentangle the effects of the policy from those of the pandemic from multiple perspectives.

Third, omitted-variable bias remains a potential threat. When relevant predictors are unobserved or unavailable in the survey, their absence can bias regression estimates if the omitted factors correlate with both the explanatory variables and the error term. In regression models, the specification of variable combinations poses a challenge to the robustness of empirical results. When necessary control variables are either unavailable in the survey data or are inherently unobservable, they cannot be included in the models. If these omitted variables are correlated with the residuals in the regression models, this may lead to biased findings. Therefore, it is important to assess the sensitivity of current findings to potential omitted-variable bias as much as possible.

To address observed confounding more rigorously, an inverse probability weighted regression adjustment (IPWRA) model was estimated to obtain average treatment effects on the treated (ATT) for shadow education duration, family income, and survey year. To address the influence of confounding variables more rigorously, we employed an inverse probability weighted regression adjustment (IPWRA) model to further examine the Average treatment effect on the treated regarding the impact of shadow education duration, family income, and survey year on adolescents’ mental health. The IPWRA procedure combines propensity score weighting with regression adjustment, delivering doubly robust estimates when either the treatment model or the outcome model is correctly specified (

Cattaneo, 2010). All control variables were included in both stages, and balance diagnostics confirmed satisfactory overlap. The final results are presented in

Table 4.

Because IPWRA requires categorical treatments, shadow education duration and family income were each divided into three groups. Shadow education categories matched prior analyses, whereas family income was split into tertiles.

Model M9 presents the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) for different levels of shadow education duration on adolescent mental health. Although the coefficients cannot be directly compared with those in Model M2, a consistent nonlinear trend is observed. Compared to adolescents with insufficient shadow education, those receiving an appropriate amount exhibit significant advantages in mental health outcomes. However, adolescents with excessive shadow education do not display statistically significant benefits.

Model M10 examines the impact of different family income levels, using the low-income group as the reference. The depression levels among adolescents in the middle-income group are significantly lower compared to those in the low-income group. Additionally, adolescents in the high-income group not only exhibit substantially lower depression levels than those in the low-income group, but the absolute magnitude of the coefficient is also greater than that of the middle-income group. This finding is consistent with the results from Model M3, suggesting that higher family income may be associated with sustained improvements in adolescent mental health.

Model M11 investigates the effects of survey year, with the pre-2018 cohort serving as the reference group. Depression levels among adolescents in the 2020 group are significantly higher. Similarly, depression levels in the 2022 group are also significantly elevated compared to the pre-2018 group, although the absolute coefficient is lower than that of the 2020 group. This is in line with the results of Model M4, indicating that the implementation of the “Double Reduction” policy has contributed to relative improvements in adolescent mental health after 2021.

Overall, after accounting for a comprehensive set of confounding factors using the IPWRA model, the effects of shadow education duration, family income, and survey year remain consistent with those observed in the baseline models. This further reinforces the robustness of Hypotheses H1, H2, and H3.

To separate policy effects from pandemic effects more clearly, adolescents were stratified by shadow education participation status, and multilevel regressions were re-estimated within each stratum. This approach is based on the assumption that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescents’ participation in shadow education and their mental health is likely broad and relatively uniform. Regardless of whether adolescents engaged in shadow education, it is probable that they experienced similar changes during the pandemic period.

In contrast, the “Double Reduction” policy specifically targets participation in shadow education, suggesting that its influence on adolescents’ mental health may differ between the two groups. Therefore, if significant differences in mental health outcomes are observed between adolescents participating in shadow education and those who do not after 2021; this would suggest that these outcomes are more likely attributable to the “Double Reduction” policy rather than to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

To address this, we performed a stratified multilevel regression analysis based on participation status, focusing on the association between survey year and depression levels. The grouped regression coefficients are presented in

Figure 5.

The results depicted in

Figure 5 indicate that, using the 2018 cohort as the reference group, adolescents in the 2020 cohort exhibited a significant increase in depression levels, regardless of their participation in shadow education. This finding aligns with our theoretical analysis, suggesting that the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic had a relatively uniform and immediate negative impact on the mental health of all adolescents.

However, for adolescents in the 2022 cohort, those participating in shadow education experienced only a slight decrease in depression levels, while those not participating in shadow education showed a more pronounced decline, with no statistically significant difference compared to the 2018 cohort. This differential impact is difficult to explain solely from the perspective of the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, the implementation of the “Double Reduction” policy may offer a plausible explanation for this phenomenon.

For adolescents engaged in shadow education, a significant proportion remain excessively involved, which considerably weakens the positive effects of the “Double Reduction” policy on their mental health. In contrast, for those not participating in shadow education, the policy has effectively reduced the social pressures and peer competition associated with shadow education. This alleviation of stress has benefited not only the mental health of these adolescents, but also the well-being of their families.

Considering both the consistency and variability in outcomes, the “Double Reduction” policy appears to exert a distinct and independent influence, separate from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

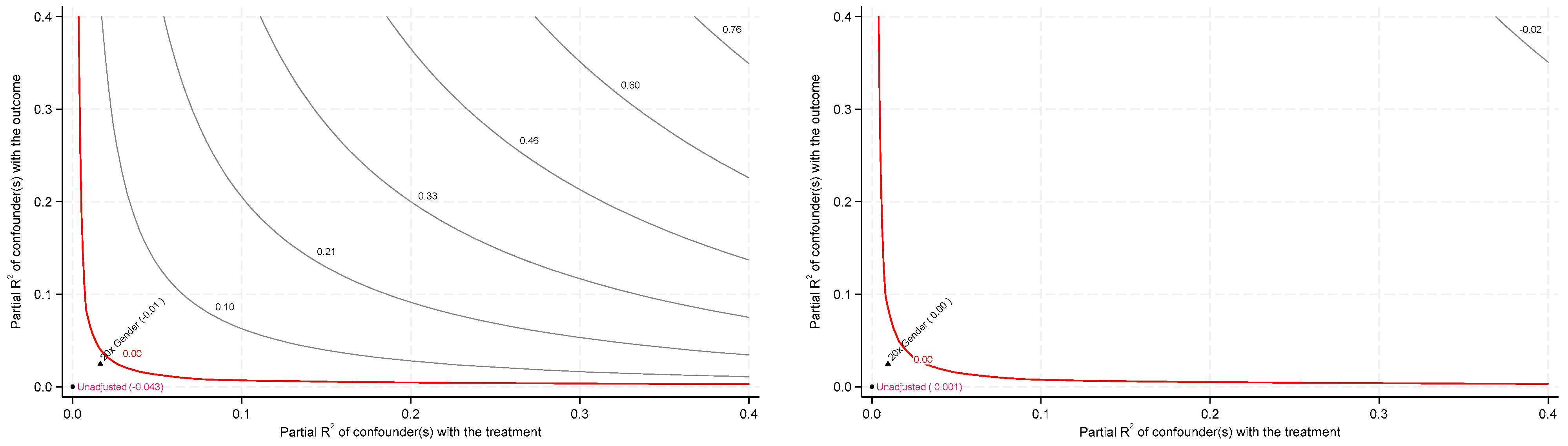

To further assess the sensitivity of our findings to potential omitted-variable bias, we conducted a sensitivity analysis based on the OLS model, following the approach proposed by

Cinelli et al. (

2020). The core idea of this analysis is to determine the degree of correlation an unobserved confounder would need to have with the key explanatory variables to invalidate the original results. If this required correlation is particularly high, it implies the greater robustness of the original findings to omitted-variable bias. The results of the sensitivity analysis are presented in

Figure 6.

The results presented in

Figure 6 demonstrate that, whether shadow education duration or its squared term is used as the variable of interest in the sensitivity analysis, the existing findings remain largely unchanged, even if the strength of an unobserved confounder were 20 times greater than that of the gender variable—that is, if the correlation between the unobserved confounder and either shadow education duration or its squared term were 20 times that of gender. Given that such a scenario is highly unlikely in practice, these results suggest that the estimated effects of shadow education duration are relatively insensitive to omitted-variable bias and exhibit considerable robustness.

5. Discussion

Based on large-scale survey data collected in China between 2016 and 2022, this study investigates the impact of shadow education duration on adolescent depression levels while considering differences arising from household income levels and policy environments. Globally, there is a growing consensus on the importance of safeguarding adolescent mental health. While the influence of education on adolescent mental health has received significant attention, most research has focused exclusively on formal schooling within educational institutions (

Garaigordobil, 2023;

X. Luo et al., 2022). In contrast, the increasing prevalence of shadow education worldwide has been studied primarily from the perspective of academic outcomes and social inequality (

Guo et al., 2020;

Jansen et al., 2023). Consequently, theoretical integration between the growing emphasis on adolescent mental health and the expanding study of shadow education remains limited. Against this backdrop, the present study seeks to bridge this gap by examining the nonlinear relationship between shadow education and adolescent mental health, while exploring the interactive influences of family and social environments. Specifically, three main theoretical findings emerge.

First, shadow education demonstrates a nonlinear effect on adolescent mental health. Using depression as the primary indicator, the duration of shadow education emerges as a critical factor in determining its psychological impact. When the duration of shadow education remains within a moderate range (0.1–20.40 h per week), increased participation appears to alleviate academic and psychological stress, supporting the view that shadow education can serve as a source of emotional support (

Sun et al., 2020;

Zheng et al., 2020). Within this range, shadow education contributes to improved academic performance and self-efficacy, offering psychological reassurance for both adolescents and their parents. However, when the duration exceeds this reasonable threshold (more than 20.40 h per week), further increases do not enhance mental health and may impose adverse effects. This finding aligns with recent arguments that shadow education can become a new source of psychological stress (

Ahn & Yoo, 2022;

Moreno & Jurado, 2024;

Yao & Chen, 2023). Excessive time spent in shadow education encroaches on adolescents’ sleep and leisure time, while imposing additional academic expectations and pressures—factors that are well established as risks for deteriorating mental health (

Pearlin, 1989;

Xu et al., 2024).

These findings suggest that the relationship between shadow education and adolescent mental health is best characterized by a nonlinear U-shaped curve, as opposed to a simple linear association. By considering the duration of shadow education, this study offers a unified framework to address the ongoing debate: shadow education within a moderate threshold may mitigate psychological stress, whereas excessive participation imposes a new psychological burden. Notably, this type of nonlinear—U-shaped—relationship has been observed not only between shadow education and academic achievement (

Hof, 2014), but also across various lifestyle factors and adolescent mental health outcomes (

Qu et al., 2025). Therefore, research on shadow education or adolescent mental health should move beyond dichotomous measures (such as participation versus non-participation) and instead distinguish among insufficient, appropriate, and excessive involvement, thereby providing a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of these trends.

Building on the foregoing discussion of potential confounders, it is equally important to recognize the methodological constraints that limit any strict causal interpretation of our results. Because the survey data do not permit full adjustment for unobservable factors—such as students’ intrinsic learning motivation, baseline academic ability, parental expectations, or classroom teaching styles (

L. C. Wang, 2015)—the nonlinear association we document between shadow education hours and depressive symptoms should be understood as a descriptive pattern that emerges from the joint influence of individual, family, and institutional dynamics rather than as evidence of a deterministic causal process. In this study, the term “mental health costs” therefore denotes the statistically significant relationships detected between shadow education duration and adolescent depressive symptoms. It does not imply a proven causal pathway. Clarifying such pathways will require future research that deploys longitudinal or experimental designs capable of tracking adolescents over time and isolating time-ordered effects.

For the same reason, the estimated threshold of approximately 21 h per week should not be treated as a definitive causal benchmark. This threshold is best understood as a reference point rather than a strict boundary, recognizing the inherent variability in adolescents’ educational experiences and the potential for heterogeneity across different groups.

To probe the robustness of this inflection point, we re-specified the “appropriate education” range as 0.1–14 h (about 2 h per day) and 0.1–28 h (about 4 h per day), and then re-estimated multilevel binary logistic models using 14-hour and 28-hour cut-offs, respectively. By comparing findings across multiple thresholds, the consistency and reliability of the 21-hour benchmark could be more thoroughly assessed. The 14-hour specification yielded coefficients and levels of statistical significance that closely mirror those of the 21-hour model. Higher household income consistently reduced the odds of both insufficient education and excessive education, and the likelihood of either form of education was significantly lower in 2022 than in the pre-2018 reference period. These results indicate a stable pattern: regardless of whether the threshold is set at 14 or 21 h, higher household income remains a protective factor against both insufficient and excessive shadow education, and the prevalence of these phenomena declined following education policy shifts in 2022. These results indicate that key predictors, such as household income and survey year, remain stable across alternative threshold definitions. This consistency lends credibility to the 21-hour inflection point as a reasonable reference derived from the statistical patterns present in the data.

When the threshold was raised to 28 h, point estimates changed only marginally. Higher-income families remained significantly less likely to fall into the insufficient education and excessive education, although the latter effect was no longer statistically significant. At the 28-hour threshold, higher-income families continued to exhibit a reduced likelihood of both insufficient and excessive education; however, the effect on excessive education, while directionally similar, no longer reached statistical significance. Likewise, the 2022 survey wave was associated with significantly less insufficient education, whereas its relation to excessive education dropped below conventional significance levels. These shifts in statistical significance, particularly for excessive education, likely reflect limitations in statistical power due to a sharply reduced number of adolescents reporting more than 28 h per week of shadow education. As the cutoff increases, the pool of cases classified as excessive education diminishes, making it more difficult to detect robust associations and potentially introducing estimation bias.

To address the concern about the stability of the 21-hour threshold across subsamples, further subgroup analyses were conducted. The results are presented in

Table 5.

The results reveal noticeable variations in the inflection points across these subgroups, as identified in models M12 through M17. Specifically, model M12 and M13 demonstrated that the turning point for male adolescents was approximately 18.5 h per week, while for females it was around 28 h per week. Similarly, model M14 and M15 showed that, by age group, adolescents aged 13 years and above exhibited an inflection point at 16.5 h per week, whereas those aged 12 years or below exhibited a turning point at 28.5 h per week. Finally, models M16 and M17 revealed regional differences, with the turning point for adolescents in eastern areas being approximately 25 h per week, whereas for those in central and western areas, it was significantly lower at 9 h per week.

These findings suggest that the 21-hour threshold is an aggregate average across the sample, rather than a universal standard applicable to all subgroups. The observed differences likely reflect variations in individual characteristics, cultural expectations, educational resources, and social environments, underscoring the need for nuanced interpretations of the threshold across diverse contexts.

While definitive explanations for these differences require further investigation, some plausible factors may help contextualize these findings. For instance, male adolescents might exhibit a lower inflection point compared to females due to potential differences in activity patterns and social expectations. Males may engage more frequently in outdoor activities, sports participation, or other physical endeavors that compete with shadow education time, potentially leading to earlier psychological or emotional fatigue. Additionally, family expectations and pressures may vary by gender, potentially influencing boys’ ability to balance shadow education with other obligations. However, these observations are speculative and should be validated by future research.

Similarly, the lower inflection point observed among adolescents aged 13 years or above might be linked to the increased academic intensity at the middle-school level, which often compresses the time available for shadow education. As academic demands rise, adolescents may face greater time constraints and heightened pressures, reducing the optimal duration of shadow education. Conversely, younger adolescents aged 12 years or below may experience a higher inflection point, possibly due to relatively lower academic workloads and greater flexibility in discretionary time use. These age-related differences, however, warrant further empirical exploration to confirm their validity and underlying mechanisms.

Regional differences further illustrate the importance of contextual factors. The higher inflection point in eastern areas may reflect differences in educational resources and competition levels, as families in these regions often invest more heavily in shadow education and emphasize academic achievement. In contrast, the substantially lower inflection point in central and western areas might be indicative of structural and socioeconomic disparities that constrain adolescents’ ability to engage in shadow education for prolonged periods. While these regional patterns provide initial insights, further studies are needed to understand how resource availability, cultural expectations, and local education systems interact to shape optimal participation thresholds.

These findings underscore the necessity of considering individual and contextual factors when interpreting this threshold, as applying it uniformly across diverse populations may overlook important nuances. Future research should prioritize examining these subgroup differences by using advanced methodologies to better capture the interplay between individual characteristics and social contexts in shaping the optimal duration of shadow education.

Taken together, these robustness checks suggest that the overall direction of income and cohort effects is stable across alternative definitions of ‘appropriate’ shadow education duration, yet they also underscore the provisional nature of the 21-hour threshold. While this figure is supported by statistical regularities and subgroup analyses, it should still be regarded as a practice-informed approximation rather than a definitive causal boundary. The variability in inflection points across subsamples highlights the need to account for heterogeneity when interpreting the threshold and applying it to different contexts. That figure arises from practice-informed observation and from the statistical regularities of the present dataset. It should be regarded as an initial reference point rather than a hard causal cut-off. Identifying optimal thresholds—and understanding the conditions under which shadow education becomes harmful—requires more rigorous causal inference strategies that explicitly model heterogeneity across students, families, schools, and regions. Longitudinal panel studies or randomized interventions would be particularly valuable for determining whether similar thresholds emerge in other contexts and for explicating the mechanisms through which shadow education intensity translates into mental-health outcomes.

Second, adolescents from high-income families are more likely to avoid the detrimental effects of shadow education on mental health. As a component of overall well-being, adolescent mental health is also influenced by a range of family and social factors, consistent with the theory of the social determinants of health (

Nutbeam & Lloyd, 2021;

Yeung, 2021). However, there is ongoing debate regarding the influence of family income on education and mental health. Some perspectives emphasize that high-income families may hold stronger educational expectations and set higher academic goals for their children, often adopting a strategy of concerted cultivation. When adolescents fail to meet these expectations, the resulting gap may intensify psychological stress and mental health problems (

L. Zhang, 2024). Despite these considerations, the findings of this study predominantly support the positive effects of family income. Specifically, adolescents from higher-income families not only have more opportunities to participate in shadow education, but are also more likely to select an appropriate duration of shadow education with parental support. Abundant family resources help adolescents in high-income families to better avoid the psychological stress associated with excessive shadow education and to develop stronger coping mechanisms and channels for stress relief (

Bray, 2023;

Song & Zhou, 2019).

Why, then, does higher family income tend to yield more positive mental health outcomes in the context of shadow education? One plausible explanation is that the ability of high-income families to provide both appropriate levels of shadow education and more effective channels for stress relief plays a more significant role in mediating the impact of shadow education on adolescent mental health, effectively offsetting the negative influences of higher parental expectations. Of course, whether this is the true underlying mechanism still requires more rigorous empirical testing and theoretical validation.

Extending from this, the study highlights how the negative mental health effects of shadow education are unevenly distributed across different groups. The discussion around shadow education often emphasizes its role in promoting academic achievement, and debates whether such academic consequences challenge educational equity and social equality (

Jansen et al., 2023;

W. Zhang & Bray, 2018). However, as a mechanism for the reproduction of social inequality, the connection between shadow education and social inequality is not limited to academic performance; it also encompasses mental health. Adolescents from disadvantaged backgrounds face greater challenges in gaining academic benefits from suitable shadow education and are more likely to bear the mental health costs caused by both insufficient and excessive education. This suggests that the impact of shadow education on social inequality is multifaceted: it not only involves the allocation of educational resources and improvement of academic achievement, but also extends deeply into the subjective realm of adolescents by shaping inequalities in mental health.

Third, the relationship between shadow education and adolescent mental health also reflects the influence of policy transformation. The implementation of the “Double Reduction” policy in 2021 marked a significant turning point in China’s regulatory framework for shadow education, shifting from a laissez-faire model to a more regulated approach (

W. Zhang, 2023, p. 61). This policy transition has substantial implications for adolescents’ participation in shadow education and its effects on mental health.

However, it is important to recognize the potential confounding impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Both the pandemic itself and related containment policies significantly increased the demand for shadow education outside schools, while posing enduring challenges to the mental health of adolescents and their families (

Du, 2024;

Houghton et al., 2022). In this context, the “Double Reduction” policy has produced opposing trends. Following its introduction in 2021, the overall duration of adolescents’ shadow education declined, while indicators of mental health, such as depression levels, improved. This suggests that, under stricter regulation, the public may adopt a more rational and pragmatic approach to shadow education, placing greater emphasis on ensuring appropriate participation for adolescents. Another important factor may be that the “Double Reduction” policy has, to some extent, weakened the legitimacy of shadow education, thereby reducing the peer pressure associated with participation—a factor that often drives irrational involvement (

Kim et al., 2022;

Pan et al., 2022).

By examining the impact of the “Double Reduction” policy, this study incorporates the influence of educational regulatory policies and their changes into the analysis of shadow education. Most extant research on shadow education is conducted within the context of a single country, often overlooking the pivotal role of regulatory frameworks (

Hertz et al., 2022;

Mikkonen et al., 2020). The major regulatory shift brought by China in 2021 offers an ideal case for investigating this dimension. It suggests that differences in regulatory frameworks across countries may systematically shape adolescents’ engagement in shadow education and their mental health outcomes. The implications of this finding extend beyond China, as the regulation of shadow education is a challenge faced by all nations and constitutes a critical component of each country’s educational ecosystem (

J. Luo & Chan, 2022). Specifically, the “Double Reduction” policy aims to minimize the negative effects of excessive shadow education by imposing restrictions on after-school tutoring and reducing academic burdens, thereby contributing to improved student well-being.

China’s “Double Reduction” policy serves as a unique regulatory experiment, offering insights that can inform global approaches to managing the challenges posed by shadow education. Unlike the laissez-faire approach prevalent in countries such as the United States or Canada—where private tutoring is largely unregulated and market-driven—China’s policy represents a strong, state-led intervention. This comparative perspective highlights how regulatory frameworks profoundly shape not only the scale of shadow education, but also its broader social and psychological consequences. One of the key mechanisms of the “Double Reduction” policy is the direct restriction of commercial tutoring services. Through imposing strict limits on private tutoring institutions, especially those focused on core subjects, and converting for-profit organizations into non-profits, the policy seeks to curtail the excessive expansion of the shadow education industry. This is intended to alleviate students’ academic pressure and time burden, affording them greater opportunities for rest, extracurricular activities, and holistic development. Furthermore, the policy tasks schools with greater responsibility for student learning and well-being, mandating enhanced after-school programs, diversified enrichment activities, and targeted academic support within the public education system. This school-centered approach not only reduces dependence on the private market, but also promotes educational equity by ensuring all students—regardless of socioeconomic background—have access to additional resources and support. Internationally, China’s experience demonstrates that robust policy interventions can effectively rebalance the relationship between formal and shadow education and mitigate the negative outcomes associated with unregulated private tutoring. For countries grappling with the rapid expansion of shadow education, the “Double Reduction” policy highlights the necessity of coordinated action by governments, schools, and society at large. It also raises important questions about how to develop policies that are contextually appropriate, achieve a balance between academic competitiveness and student well-being, and avoid the unintended consequences of both over-regulation and unchecked market freedom.

Returning to the Chinese context, it is clear that the impact of the “Double Reduction” policy warrants further exploration. A comprehensive understanding of this policy’s consequences requires attention not only to its immediate educational outcomes, but also to the broader social and cultural environment in which it has been implemented. This includes the need for more rigorous causal inference strategies to disentangle its effects from those of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as placing educational regulatory policies and their transformations within broader socio-cultural dynamics. For example, it remains to be studied whether the impact of the “Double Reduction” policy differs systematically between urban and rural areas—specifically, whether it exacerbates or alleviates educational inequality across these contexts. Urban–rural disparities represent a critical dimension for analysis: urban students often benefit from greater access to alternative educational resources and a wider array of non-academic enrichment activities, whereas rural students may face ongoing structural limitations, such as fewer extracurricular options and less institutional support, potentially magnifying pre-existing inequalities. Urban students may have greater access to alternative educational resources and non-academic enrichment activities, while rural students might face persistent structural limitations, potentially leading to uneven policy effects. Furthermore, the role of parental expectations, which are often closely tied to socioeconomic status, merits careful consideration (

L. C. Wang, 2015). Families from higher income strata may seek alternative forms of support or extracurricular activities to compensate for the reduction in formal shadow education, potentially maintaining or even widening existing educational disparities. In contrast, lower-income families might lack the resources to pursue such alternatives, thus experiencing the policy’s effects differently. Additionally, parental expectations—often shaped by socioeconomic status—play a pivotal role in mediating the policy’s impact (

L. C. Wang, 2015;

Yeung, 2024). Families from a higher-income strata may compensate for reduced opportunities in formal shadow education by investing in alternative forms of academic or extracurricular support, thereby maintaining or even accentuating pre-existing educational advantages. Conversely, lower-income families may lack the financial or informational resources to access such alternatives, resulting in a differentiated experience of the policy’s consequences. Moreover, adolescents’ access to non-academic enrichment opportunities—such as sports, arts, and community engagement—varies greatly by region and family background, and these opportunities can play a critical role in shaping psychological well-being and holistic development post policy intervention. The availability and uptake of non-academic enrichment, including sports, arts, and civic engagement, are highly uneven across both geographic and socioeconomic lines; these experiences are increasingly recognized as key for adolescent psychological well-being, resilience, and holistic development in the context of reduced shadow education. Understanding how the “Double Reduction” policy interacts with these sociocultural variables is essential for evaluating its long-term impacts and for informing more equitable policy adjustments to address the diverse needs of Chinese adolescents and their families. A nuanced understanding of how the “Double Reduction” policy interacts with such sociocultural variables is essential for a comprehensive evaluation of its long-term impacts. Careful attention to these dynamics will be crucial for informing the ongoing design and refinement of educational policies that not only enhance equity, but also support the diverse developmental and psychosocial needs of Chinese adolescents and their families.

This research carries several social implications and provides valuable directions for future development. Firstly, how should the goals of shadow education regulatory policies be defined? The formulation of educational policies is essential for societal development, yet it often involves contradictions and debates (

L. Wang & Hamid, 2024). Based on the findings of this study, the objective of regulation should not be to eliminate shadow education entirely, but rather to maintain it at a reasonable level of intensity and duration. Such an approach would allow for shadow education to effectively enhance adolescents’ academic performance while minimizing excessive mental health costs. This highlights the importance of determining an optimal duration for shadow education, which may vary across different cultural and social contexts. Future research should prioritize comparative studies that examine the mental health consequences of shadow education across various countries, thereby providing insights into how cultural differences shape its impacts.

Secondly, beyond participation in shadow education, how adolescents engage with it and the types of shadow education they choose to pursue are also critical issues worth considering. The duration of shadow education is not merely a key factor influencing mental health; it reflects certain characteristics and dimensions of shadow education, constituting a broader and more complex system. The implications of this study suggest that shadow education is not a homogeneous entity, but rather encompasses a variety of differences. The manner in which adolescents engage in shadow education requires further exploration. For instance, whether shadow education is conducted through one-on-one sessions or in group settings, whether shadow educators undergo professional training, and whether the content of shadow education aligns with formal school curricula are all key characteristics that may influence the outcomes (

Hertz et al., 2022). Particularly in the era of widespread digital technology, shadow education has taken on more flexible forms (

Bray, 2024). It remains to be determined whether online and offline forms of shadow education led to differing academic performance and mental health outcomes. These endeavors not only necessitate a more systematic delineation of the theoretical underpinnings of shadow education, but also require updated methods of data collection to obtain more targeted survey data.

Finally, the unequal characteristics of shadow education and their implications for mental health demand further investigation. Shadow education, as an avenue for transmitting and accumulating economic, social, and cultural capital, is deeply embedded within wider societal structures of inequality, and its mental health consequences cannot be understood in isolation from these broader contexts (

Yeung, 2022). As a form of economic capital, family income plays a critical role in shaping the mental health consequences of shadow education, highlighting its intersection with broader mechanisms of social inequality. These inequalities can manifest at multiple levels, including familial, urban–rural, and regional disparities. For instance, at the familial level, a family’s social resources often encompass multiple dimensions—such as economic, social, and cultural capital—which interact and transform one another. Different combinations of these capitals may result in varying mental health outcomes associated with shadow education. At the urban-rural level, disparities in educational resource distribution further exacerbate inequalities. Adolescents in resource-rich urban areas benefit from higher-quality formal education and shadow education, gaining greater access to prestigious universities and adopting more rational attitudes toward shadow education. In contrast, adolescents in resource-scarce rural areas face dual disadvantages from both formal and shadow education, experiencing higher mental health costs. At the regional level, apart from differences in educational resources, cultural and conceptual factors are also highly significant. Specifically, different regions of China may maintain distinct parenting cultures and values, which not only affect the types and extent of shadow education parents are willing to invest in, but also shape parent–adolescent emotional interaction patterns. As a result, the relationship between adolescent shadow education and mental health may systematically differ across regions, shaped jointly by regional resources and cultures. Future research would benefit from examining how specific configurations of family capital intersect with contextual factors, such as regional educational competition and urban–rural disparities, to produce differentiated mental health outcomes. These investigations would provide deeper insights into the complex dynamics of shadow education and its broader social implications.