Examining Trauma Cognitions as a Mechanism of the BRITE Intervention for Female-Identifying Individuals with PTSD Symptoms and Alcohol Misuse

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

Conditions

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Post-Traumatic Stress Severity

2.3.2. Average Drinks Consumed

2.3.3. Trauma Cognitions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

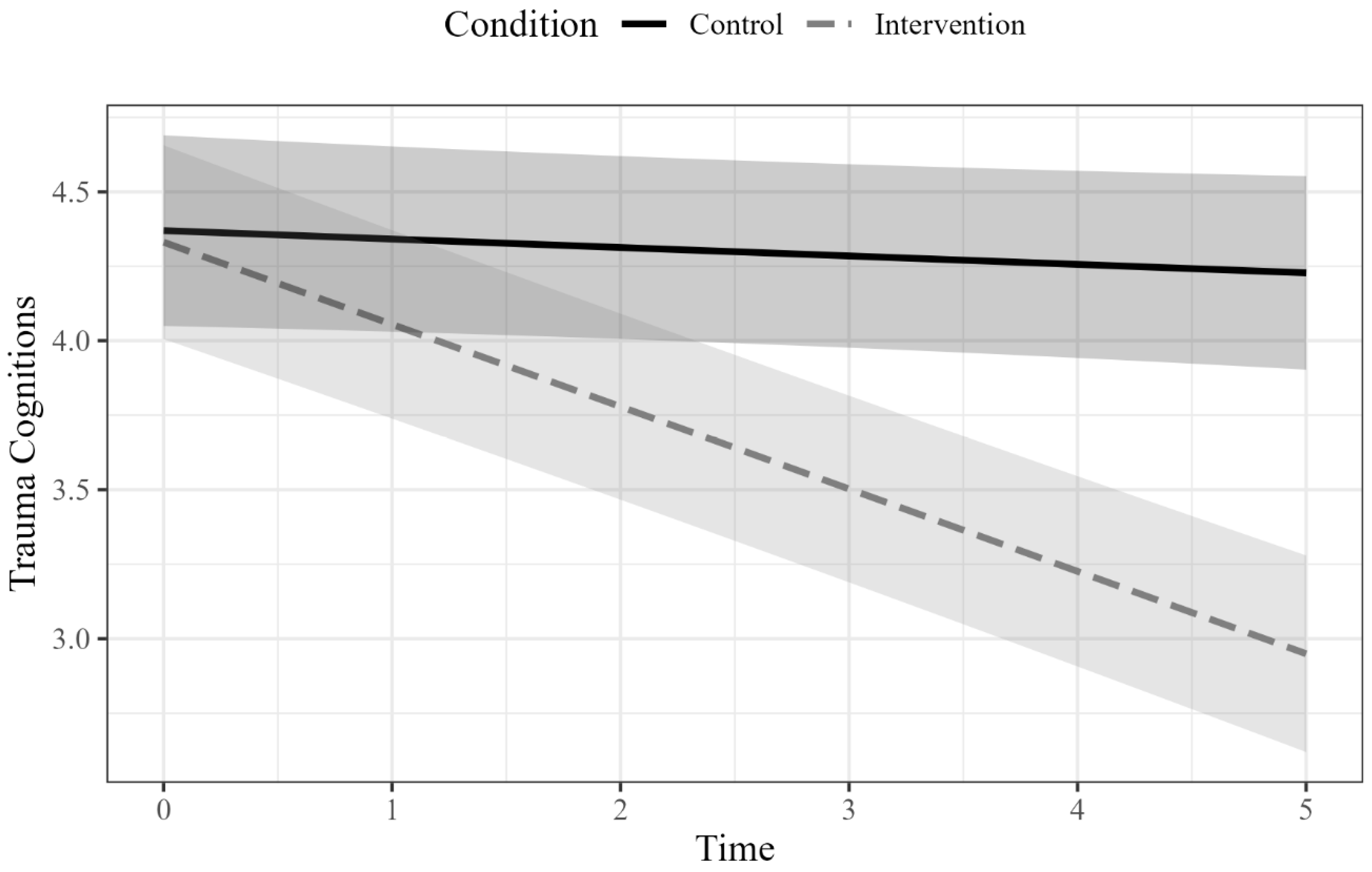

3.1. PTSD Symptom Severity

3.2. Average Drinks on Drinking Days

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alpert, E., Shotwell Tabke, C., Cole, T. A., Lee, D. J., & Sloan, D. M. (2023). A systematic review of literature examining mediators and mechanisms of change in empirically supported treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 103, 102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstadter, A. B., McCauley, J. L., Ruggiero, K. J., Resnick, H. S., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2008). Service utilization and help seeking in a national sample of female rape victims. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 59(12), 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedard-Gilligan, M. A., Masters, N. T., Ojalehto, H., Simpson, T. L., Stappenbeck, C., & Kaysen, D. (2020). Refinement and pilot testing of a brief, early intervention for PTSD and alcohol use following sexual assault. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 27(4), 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisson, J. I., Berliner, L., Cloitre, M., Forbes, D., Jensen, T. K., Lewis, C., Monson, C. M., Olff, M., Pilling, S., Riggs, D. S., Roberts, N. P., & Shapiro, F. (2019). The international society for traumatic stress studies new guidelines for the prevention and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: Methodology and development process. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(4), 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, T. A., Griffiths, R., Dixon, J. E., & Hines, S. (2020). Identifying functional mechanisms in psychotherapy: A scoping systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Schilo, L., & Grimm, K. J. (2018). Using residualized change versus difference scores for longitudinal research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(1), 32–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domino, J. L., Whiteman, S. E., Weathers, F. W., Blevins, C. T., & Davis, M. T. (2020). Predicting PTSD and depression following sexual assault: The role of perceived life threat, post-traumatic cognitions, victim-perpetrator relationship, and social support. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 29(6), 680–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunmore, E., Clark, D. M., & Ehlers, A. (1999). Cognitive factors involved in the onset and maintenance of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after physical or sexual assault. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37(9), 809–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunmore, E., Clark, D. M., & Ehlers, A. (2001). A prospective investigation of the role of cognitive factors in persistent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after physical or sexual assault. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39(9), 1063–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, E. R., Jaffe, A. E., Bedard-Gilligan, M., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2023). PTSD in the year following sexual assault: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(2), 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, E. R., Schallert, M., Lee, C. M., & Kaysen, D. (2024). Pilot randomized clinical trial of an app-based early intervention to reduce PTSD and alcohol use following sexual assault. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 16(Suppl. 3), S668–S678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, E. R., & Schumacher, J. A. (2018). Preventing posttraumatic stress related to sexual assault through early intervention: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(4), 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, D. M., Mok, D. S., & Briere, J. (2004). Adult sexual assault: Prevalence, symptomatology, and sex differences in the general population. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17(3), 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairbrother, N., & Rachman, S. (2006). PTSD in victims of sexual assault: Test of a major component of the Ehlers–Clark theory. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 37(2), 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedina, L., Holmes, J. L., & Backes, B. L. (2018). Campus sexual assault: A systematic review of prevalence research from 2000 to 2015. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(1), 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, R. A., Cortés, P. F., Marín, H., Vergés, A., Gillibrand, R., & Repetto, P. (2022). The ABCDE psychological first aid intervention decreases early PTSD symptoms but does not prevent it: Results of a randomized-controlled trial. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2031829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E. B., Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Tolin, D. F., & Orsillo, S. M. (1999). The posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): Development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 11(3), 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E. B., McLean, C. P., Zang, Y., Zhong, J., Rauch, S., Porter, K., Knowles, K., Powers, M. B., & Kauffman, B. Y. (2016). Psychometric properties of the posttraumatic stress disorder symptom scale interview for DSM–5 (PSSI–5). Psychological Assessment, 28(10), 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Huang, S. H., & Bonanno, G. A. (2018). Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: A review and statistical evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 63, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawn, S. E., Cusack, S. E., & Amstadter, A. B. (2020). A systematic review of the self-medication hypothesis in the context of posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid problematic alcohol use. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(5), 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaysen, D., Atkins, D. C., Moore, S. A., Lindgren, K. P., Dillworth, T., & Simpson, T. (2011). Alcohol use, problems, and the course of posttraumatic stress disorder: A prospective study of female crime victims. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 7(4), 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaysen, D., Simpson, T., Dillworth, T., Larimer, M. E., Gutner, C., & Resick, P. A. (2006). Alcohol problems and posttraumatic stress disorder in female crime victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19(3), 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kazdin, A. E. (2009). Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychotherapy Research, 19(4–5), 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A. E. (2011). Evidence-based treatment research: Advances, limitations, and next steps. American Psychologist, 66(8), 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Sonnega, A., Bromet, E., Hughes, M., & Nelson, C. B. (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52(12), 1048–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khantzian, E. J. (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4(5), 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, N. K., Berke, D. S., Rhodes, C. A., Steenkamp, M. M., & Litz, B. T. (2021). Self-blame and PTSD following sexual assault: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(5–6), NP3153–NP3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, K. J., Rubin, A., Brief, D. J., Enggasser, J. L., Roy, M., Solhan, M., Helmuth, E., Rosenbloom, D., & Keane, T. M. (2017). Sexual traumatic event exposure, posttraumatic stress symptomatology, and alcohol misuse among women: A critical review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 24(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K., & Ullman, S. E. (2016). Alcohol and sexual assault victimization: Research findings and future directions. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 31, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R., Helm, J., Luciano, M., Haller, M., & Norman, S. B. (2023). The role of posttraumatic cognitions in integrated treatments for co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 16(Suppl. 3), S532–S539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, A. C., Browne, D., Bryant, R. A., O’Donnell, M., Silove, D., Creamer, M., & Horsley, K. (2009). A longitudinal analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of posttraumatic symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 118(1–3), 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, C. P., Su, Y. J., & Foa, E. B. (2015). Mechanisms of symptom reduction in a combined treatment for comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messman-Moore, T., Ward, R. M., Zerubavel, N., Chandley, R. B., & Barton, S. N. (2015). Emotion dysregulation and drinking to cope as predictors and consequences of alcohol-involved sexual assault. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(4), 601–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R., Meyerson, L. A., Long, P. J., Marx, B. P., & Simpson, S. M. (2002). Sexual assault and alcohol use: Exploring the self-medication hypothesis. Violence and Victims, 17(2), 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter-Hagene, L. C., & Ullman, S. E. (2018). Longitudinal effects of sexual assault victims’ drinking and self-blame on posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(1), 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resick, P. A., Monson, C. M., & Chard, K. M. (2016). Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: A comprehensive manual. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, H. S., Acierno, R., Amstadter, A. B., Self-Brown, S., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2007). An acute post-sexual assault intervention to prevent drug abuse: Updated findings. Addictive Behaviors, 32(10), 2032–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., De La Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev, A. Y., Gevonden, M., Ratanatharathorn, A., Laska, E., van der Mei, W. F., Qi, W., Lowe, S., Lai, B. S., Bryant, R. A., Delahanty, D., Matsuoka, Y. J., Olff, M., Schnyder, U., Seedat, S., deRoon-Cassini, T. A., Kessler, R. C., & Koenen, K. C. (2019). Estimating the risk of PTSD in recent trauma survivors: Results of the international consortium to predict PTSD (ICPP). World Psychiatry, 18(1), 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K. M., Chung, Y. K., Shin, Y. J., Kim, M., Kim, N. H., Kim, K. A., Lee, H., & Chang, H. Y. (2017). Post-traumatic cognition mediates the relationship between a history of sexual abuse and the post-traumatic stress symptoms in sexual assault victims. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 32(10), 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (1992). Timeline follow-back. In Measuring alcohol consumption (pp. 41–72). Humana Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobell, L. C., Sobell, M. B., Leo, G. I., & Cancilla, A. (1988). Reliability of a timeline method: Assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. British Journal of Addiction, 83(4), 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stappenbeck, C. A., Luterek, J. A., Kaysen, D., Rosenthal, C. F., Gurrad, B., & Simpson, T. L. (2015). A controlled examination of two coping skills for daily alcohol use and PTSD symptom severity among dually diagnosed individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 66, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tingley, D., Yamamoto, T., Hirose, K., Keele, L., & Imai, K. (2014). mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 59(5), 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp, J. C., Worley, M. J., Straus, E., Angkaw, A. C., Trim, R. S., & Norman, S. B. (2020). Bidirectional relationship of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom severity and alcohol use over the course of integrated treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 34(4), 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullman, S. E. (1999). Social support and recovery from sexual assault: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 4(3), 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(3), 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, E. L., Jiang, C., Jenkins, Q., Millette, M. J., Caldwell, M. T., Mehari, K. S., & Marsh, E. E. (2022). Trends in US emergency department use after sexual assault, 2006–2019. JAMA Network Open, 5(10), e2236273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatzick, D., Jurkovich, G., Heagerty, P., Russo, J., Darnell, D., Parker, L., Roberts, M. K., Moodliar, R., Engstrom, A., Wang, J., Bulger, E., Whiteside, L., Nehra, D., Palinkas, L. A., Moloney, K., & Maier, R. (2021). Stepped collaborative care targeting posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and comorbidity for US trauma care systems. JAMA Surgery, 156(5), 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre PTCI total | - | |||||||

| 2. Post PTCI total | 0.48 ** | - | ||||||

| 3. Pre Self-blame | 0.73 ** | 0.33 * | ||||||

| 4. Post Self-blame | 0.46 ** | 0.86 ** | 0.50 ** | |||||

| 5. Pre PSSI | 0.52 ** | 0.33 * | 0.28 * | 0.20 | - | |||

| 6. Follow-up PSSI | 0.50 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.25 | 0.51 ** | 0.60 ** | - | ||

| 7. Pre Average Drinks | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.22 | −0.14 | 0.18 | 0.16 | - | |

| 8. Follow-up Average Drinks | −0.25 | −0.11 | −0.29 | −0.10 | −0.23 | −0.20 | 0.44 ** | - |

| M | 4.22 | 3.51 | 4.82 | 3.95 | 32.84 | 16.75 | 4.1 | 3.19 |

| SD | 0.85 | 1.16 | 1.24 | 1.67 | 8.33 | 10.3 | 1.45 | 1.60 |

| Range | 2.15–6.15 | 1.09–5.73 | 1.8–7 | 1–6.6 | 11–54 | 3–48 | 1.86–7.89 | 0–7.30 |

| Outcome | b | SE | 95% CI (Lower, Upper) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD symptom severity | ||||

| Total trauma cognitions as mediator | ||||

| Condition → Δ Trauma Cognitions (a path) | −0.66 | 0.26 | 0.014 | |

| Δ Trauma Cognitions → PTSD symptom severity (b path) | −0.78 | 1.03 | 0.461 | |

| Condition → PTSD symptom severity (total effect, c path) | −9.56 | 2.07 | <0.001 | |

| Condition → PTSD symptom severity (direct effect, c’ path) | −10.07 | 2.28 | <0.001 | |

| Indirect effect (a × b) | 0.52 | 0.98 | [−1.39, 2.44] | |

| Self-blame cognitions as mediator | ||||

| Condition → Δ Self-blame Cognitions (a path) | −0.70 | 0.38 | 0.071 | |

| Δ Self-blame Cognitions → PTSD symptom severity (b path) | −0.75 | 0.71 | 0.303 | |

| Condition → PTSD symptom severity (total effect, c path) | −9.56 | 2.07 | <0.001 | |

| Condition → PTSD symptom severity (direct effect, c’ path) | −10.07 | 2.21 | <0.001 | |

| Indirect effect (a × b) | 0.52 | 0.79 | [−1.02, 2.07] | |

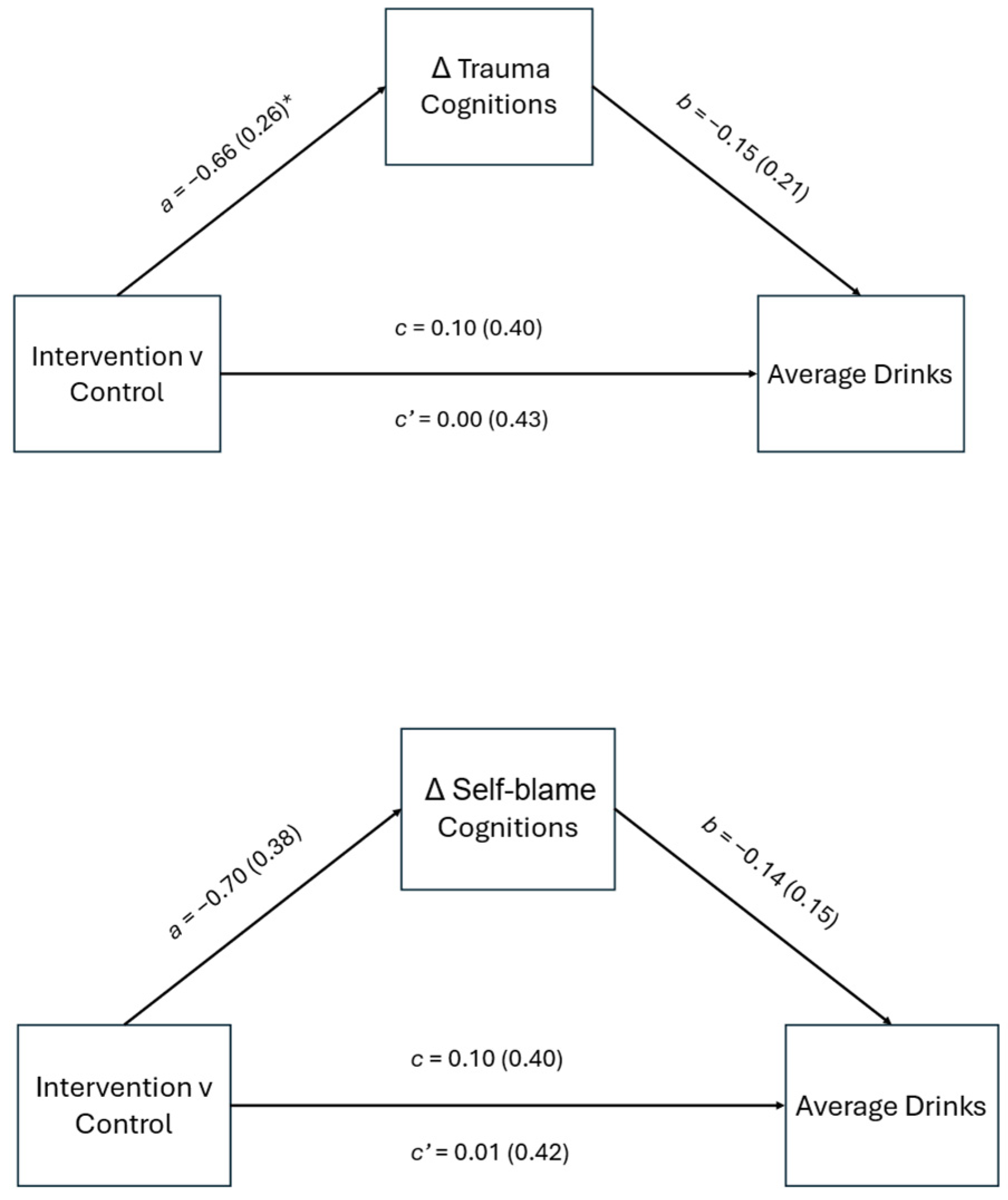

| Average drinks on drinking days | ||||

| Total trauma cognitions as mediator | ||||

| Condition → Δ Trauma Cognitions (a path) | −0.66 | 0.26 | 0.014 | |

| Δ Trauma Cognitions → Average drinks (b path) | −0.15 | 0.21 | 0.498 | |

| Condition → Average drinks (total effect, c path) | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.804 | |

| Condition → Average drinks (direct effect, c’ path) | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.996 | |

| Indirect effect (a × b) | 0.10 | 0.18 | [−0.25, 0.45] | |

| Self-blame cognitions as mediator | ||||

| Condition → Δ Self-blame Cognitions (a path) | −0.70 | 0.38 | 0.071 | |

| Δ Self-blame Cognitions → Average drinks (b path) | −0.14 | 0.15 | 0.361 | |

| Condition → Average drinks (total effect, c path) | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.804 | |

| Condition → Average drinks (direct effect, c’ path) | 0.01 | 0.42 | 0.988 | |

| Indirect effect (a × b) | 0.09 | 0.27 | [−0.44, 0.63] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lehinger, E.A.; Joseph, M.; Lebeaut, A.; Graupensperger, S.; Kaysen, D.; Bedard-Gilligan, M.A. Examining Trauma Cognitions as a Mechanism of the BRITE Intervention for Female-Identifying Individuals with PTSD Symptoms and Alcohol Misuse. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070872

Lehinger EA, Joseph M, Lebeaut A, Graupensperger S, Kaysen D, Bedard-Gilligan MA. Examining Trauma Cognitions as a Mechanism of the BRITE Intervention for Female-Identifying Individuals with PTSD Symptoms and Alcohol Misuse. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):872. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070872

Chicago/Turabian StyleLehinger, Elizabeth A., Molly Joseph, Antoine Lebeaut, Scott Graupensperger, Debra Kaysen, and Michele A. Bedard-Gilligan. 2025. "Examining Trauma Cognitions as a Mechanism of the BRITE Intervention for Female-Identifying Individuals with PTSD Symptoms and Alcohol Misuse" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070872

APA StyleLehinger, E. A., Joseph, M., Lebeaut, A., Graupensperger, S., Kaysen, D., & Bedard-Gilligan, M. A. (2025). Examining Trauma Cognitions as a Mechanism of the BRITE Intervention for Female-Identifying Individuals with PTSD Symptoms and Alcohol Misuse. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070872