Examining Longitudinal Risk and Strengths-Based Factors Associated with Depression Symptoms Among Sexual Minority Men in Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Minority Stress Among SMM

1.2. Syndemics

1.3. Strengths-Based and Protective Factors

1.3.1. Self-Esteem

1.3.2. Hope

1.3.3. Social Support

1.4. Limitations of the Current Literature

1.5. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographic Variables

Time

2.3.2. Dependent Variable

2.3.3. Independent Variables

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Bivariate Relationships

3.2. Unconditional Model

3.3. Unconditional Growth Models

3.4. Conditional Model

Random Effects of Conditional Model

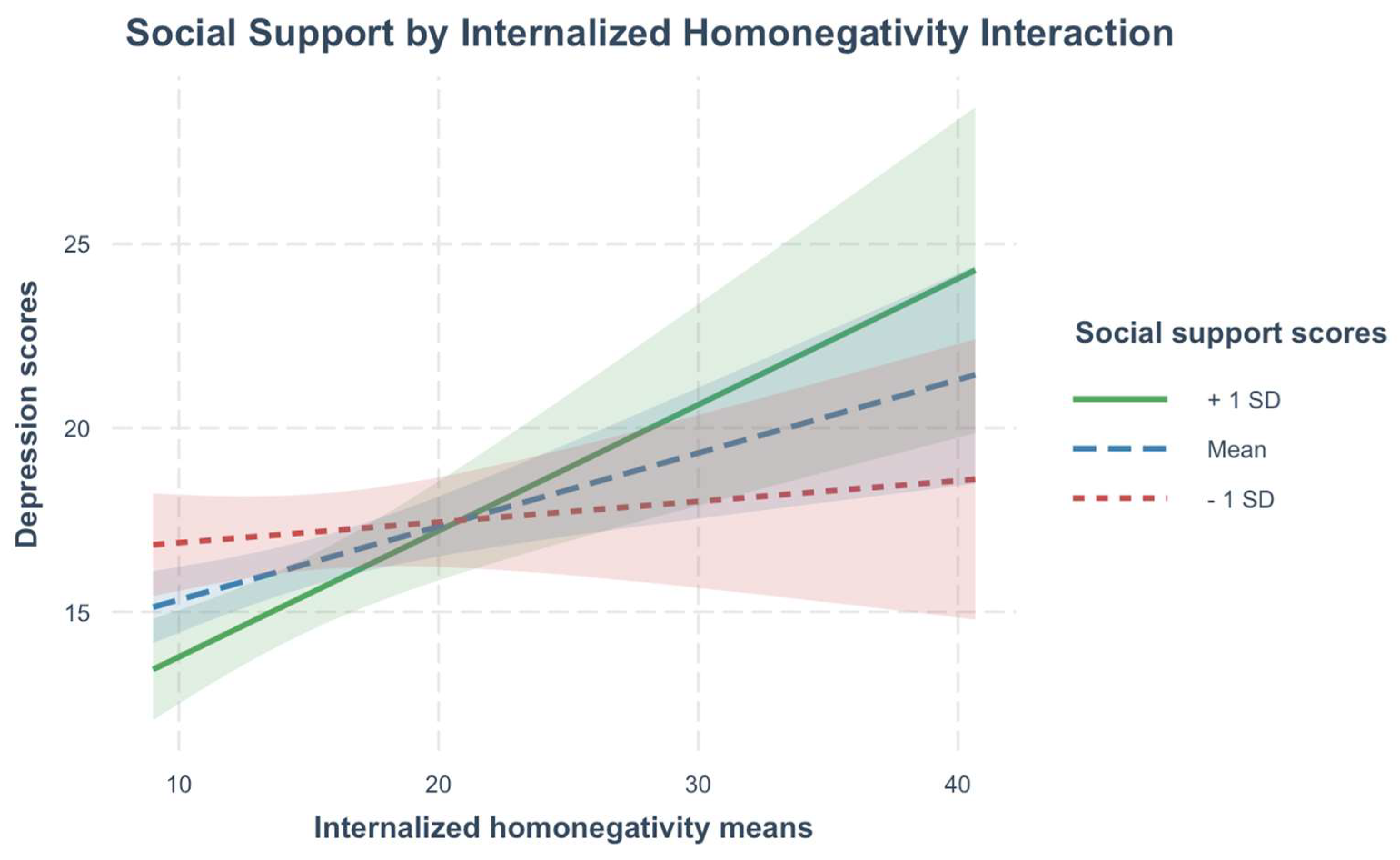

3.5. Interaction Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arreola, S. G., Neilands, T. B., & Díaz, R. (2009). Childhood sexual abuse and the sociocultural context of sexual risk among adult Latino gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health, 99(S2), S432–S438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercea, L., Pintea, S., & Kállay, É. (2023). The relationship between social support and depression in the LGBT+ population: A meta-analysis. Studia Universitatis Babeș-Bolyai Psychologia-Paedagogia, 68(2), 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, R. C., Munthe-Kaas, H. M., & Ross, M. W. (2016). Internalized homonegativity: A systematic mapping review of empirical research. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(4), 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes, J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., Desmond, D., & Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, L., Smith, P., & Rimes, K. A. (2019). Sexual orientation differences in the self-esteem of men and women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(4), 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, V. R. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. L., Matthews, D. D., Meanley, S., Brennan-Ing, M., Haberlen, S., D’Souza, G., Ware, D., Egan, J., Shoptaw, S., Teplin, L. A., Friedman, M. R., & Plankey, M. (2022). The effect of discrimination and resilience on depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older men who have sex with men. Stigma and Health, 7(1), 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, J. L., Baker, Z. G., & Tou, R. Y. (2017). Prevent the blue, be true to you: Authenticity buffers the negative impact of loneliness on alcohol-related problems, physical symptoms, and depressive and anxiety symptoms. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(5), 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A. C., & Miller, D. L. (2015). A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 317–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-H., Paul, J., Ayala, G., Boylan, R., & Gregorich, S. E. (2013). Experiences of discrimination and their impact on mental health among African American, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Latino men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, R. W. S., Egan, J. E., Kinsky, S., Friedman, M. R., Eckstrand, K. L., Frankeberger, J., Folb, B. L., Mair, C., Markovic, N., Silvestre, A., Stall, R., & Miller, E. (2019). Mental health, drug, and violence interventions for sexual/gender minorities: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 144(3), e20183367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csoti, J. P., & McLaren, S. (2024). Sexual orientation concealment, hope, and depressive symptoms among gay and bisexual men: A moderated-moderation model. Psychology & Sexuality, 16(1), 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G. (2014). The new statistics: Why and how. Psychological Science, 25(1), 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2011). The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 583–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, J. P., & Vasquez, E. P. (2011). A pilot study to evaluate ethnic/racial differences in depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and sexual behaviors among men who have sex with men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 23(2), 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dürrbaum, T., & Sattler, F. A. (2020). Minority stress and mental health in lesbian, gay male, and bisexual youths: A meta-analysis. Journal of LGBT Youth, 17(3), 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlatte, O., Dulai, J., Hottes, T. S., Trussler, T., & Marchand, R. (2015). Suicide related ideation and behavior among Canadian gay and bisexual men: A syndemic analysis. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisal, Z. A. M., Minhat, H. S., Zulkefli, N. A. M., & Ahmad, N. (2022). Biopsychosocial approach to understanding determinants of depression among men who have sex with men living with HIV: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 17(3), e0264636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2023). Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance. Current Opinion in Psychology, 51, 101579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariépy, G., Honkaniemi, H., & Quesnel-Vallée, A. (2016). Social support and protection from depression: Systematic review of current findings in Western countries. British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(4), 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S. D., Feinstein, B. A., Skidmore, W. C., & Marx, B. P. (2011). Childhood physical abuse, internalized homophobia, and experiential avoidance among lesbians and gay men. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 3(1), 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J. M., & Barnow, Z. B. (2013). Stress and social support in gay, lesbian, and heterosexual couples: Direct effects and buffering models. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(4), 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, W. J. (2018). Psychosocial risk and protective factors for depression among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer youth: A systematic review. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(3), 263–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, T. A., Noor, S. W., Adam, B. D., Vernon, J. R. G., Brennan, D. J., Gardner, S., Husbands, W., & Myers, T. (2017). Number of psychosocial strengths predicts reduced HIV sexual risk behaviors above and beyond syndemic problems among gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior, 21(10), 3035–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, T. A., Noor, S. W., Vernon, J. R. G., Kidwai, A., Roberts, K., Myers, T., & Calzavara, L. (2018). Childhood maltreatment, bullying victimization, and psychological distress among gay and bisexual men. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, F. (2022). DHARMa: Residual diagnostics for hierarchical (multi-level/mixed) regression models (Version R package version 0.4.6) [Computer software]. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DHARMa (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Hatchard, T., Levitt, E. E., Mutschler, C., Easterbrook, B., Nicholson, A. A., Boyd, J. E., Hewitt, J., Marcus, N., Tissera, T., Mawson, M., Roth, S. L., Schneider, M. A., & McCabe, R. E. (2024). Transcending: A pragmatic, open-label feasibility study of a minority-stress-based CBT group intervention for transgender and gender-diverse emerging adults. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., O’Cleirigh, C., Grasso, C., Mayer, K., Safren, S., & Bradford, J. (2012). Effect of same-sex marriage laws on health care use and expenditures in sexual minority men: A quasi-natural experiment. American Journal of Public Health, 102(2), 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herek, G. M., Cogan, J. C., Gillis, J. R., & Glunt, E. K. (1997). Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. Journal of the Gay & Lesbian Medical Assn, 2(1), 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Herrick, A. L., Stall, R., Goldhammer, H., Egan, J. E., & Mayer, K. H. (2014). Resilience as a research framework and as a cornerstone of prevention research for gay and bisexual men: Theory and evidence. AIDS and Behavior, 18(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herth, K. (1990). Fostering hope in terminally ill people. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 15(11), 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herth, K. (1993). Hope in older adults in community and institutional settings. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 14(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoy-Ellis, C. P. (2023). Minority stress and mental health: A review of the literature. Journal of Homosexuality, 70(5), 806–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, C. A., Schwartz, D. R., Roberts, K. E., Hart, T. A., Loutfy, M. R., Myers, T., & Calzavara, L. (2012). Childhood emotional abuse and psychological distress in gay and bisexual men. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 21(8), 851–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, P., Birrueta, M., Faust, E., & Brown, E. R. (2015). The role of hope in preventive interventions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(12), 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanner, M. R., Pachankis, J. E., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2022). Mechanisms linking distal minority stress and depressive symptoms in a longitudinal, population-based study of gay and bisexual men: A test and extension of the psychological mediation framework. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 90(8), 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legate, N., Weinstein, N., Ryan, W. S., DeHaan, C. R., & Ryan, R. M. (2019). Parental autonomy support predicts lower internalized homophobia and better psychological health indirectly through lower shame in lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Stigma and Health, 4(4), 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A., de Medeiros, A. G. A. P., Rolim, C., Pinheiro, K. S. C. B., Beilfuss, M., Leão, M., Castro, T., & Junior, J. A. S. H. (2019). Hope theory and its relation to depression: A systematic review. Annals of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 2(2), 1014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G., Wu, A. D., Marshall, S. K., Watson, R. J., Adjei, J. K., Park, M., & Saewyc, E. M. (2019). Investigating site-level longitudinal effects of population health interventions: Gay-straight alliances and school safety. SSM—Population Health, 7, 100350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdecke, D. (2024). sjPlot: Data visualization for statistics in social science (Version R package version 2.8.16) [Computer software]. Available online: https://strengejacke.github.io/sjPlot/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Lytle, M. C., Vaughan, M. D., Rodriguez, E. M., & Shmerler, D. L. (2014). Working with LGBT individuals: Incorporating positive psychology into training and practice. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, R. A., & Kettrey, H. H. (2016). Gay-straight alliances are associated with lower levels of school-based victimization of LGBTQ+ youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(7), 1269–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDavitt, B., Iverson, E., Kubicek, K., Weiss, G., Wong, C. F., & Kipke, M. D. (2008). Strategies used by gay and bisexual young men to cope with heterosexism. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 20(4), 354–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, S., Jude, B., & McLachlan, A. J. (2008). Sense of belonging to the general and gay communities as predictors of depression among Australian gay men. International Journal of Men’s Health, 7(1), 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereish, E. H., & Poteat, V. P. (2015). A relational model of sexual minority mental and physical health: The negative effects of shame on relationships, loneliness, and health. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(3), 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I. H. (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongelli, F., Perrone, D., Balducci, J., Sacchetti, A., Ferrari, S., Mattei, G., & Galeazzi, G. M. (2019). Minority stress and mental health among LGBT populations: An update on the evidence. Minerva Psichiatrica, 60(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, R. L., Starks, T. J., Grov, C., & Parsons, J. T. (2018). Internalized homophobia and drug use in a national cohort of gay and bisexual men: Examining depression, sexual anxiety, and gay community attachment as mediating factors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(4), 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, B., & Subich, L. M. (2004). Examining the moderating role of self-esteem in the link between experiences of perceived sexist events and psychological distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(1), 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S., McLaren, S., McLachlan, A. J., & Jenkins, M. (2015). Sense of belonging to specific communities and depressive symptoms among Australian gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(6), 804–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musca, S. C., Kamiejski, R., Nugier, A., Méot, A., Er-Rafiy, A., & Brauer, M. (2011). Data with hierarchical structure: Impact of intraclass correlation and sample size on type-I error. Frontiers in Psychology, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2010). Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(8), 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamake, S. T., Walch, S. E., & Raveepatarakul, J. (2016). Discrimination and sexual minority mental health: Mediation and moderation effects of coping. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(2), 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Operario, D., Sun, S., Bermudez, A. N., Masa, R., Shangani, S., Van Der Elst, E., & Sanders, E. (2022). Integrating HIV and mental health interventions to address a global syndemic among men who have sex with men. The Lancet HIV, 9(8), e574–e584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U., & Robins, R. W. (2022). Is high self-esteem beneficial? Revisiting a classic question. American Psychologist, 77(1), 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea, J., Jenkins, R., Nicholls, D., Downs, J., & Hudson, L. D. (2024). Prevalence, severity, and risk factors for mental disorders among sexual and gender minority young people: A systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachankis, J. E. (2007). The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin, 133(2), 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachankis, J. E., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Rendina, H. J., Safren, S. A., & Parsons, J. T. (2015a). LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachankis, J. E., Mahon, C. P., Jackson, S. D., Fetzner, B. K., & Bränström, R. (2020). Sexual orientation concealment and mental health: A conceptual and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(10), 831–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachankis, J. E., Rendina, H. J., Restar, A., Ventuneac, A., Grov, C., & Parsons, J. T. (2015b). A minority stress—Emotion regulation model of sexual compulsivity among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. Health Psychology, 34(8), 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachankis, J. E., Sullivan, T. J., Feinstein, B. A., & Newcomb, M. E. (2018). Young adult gay and bisexual men’s stigma experiences and mental health: An 8-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 54(7), 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakula, B., Shoveller, J., Ratner, P. A., & Carpiano, R. (2016). Prevalence and co-occurrence of heavy drinking and anxiety and mood disorders among gay, lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual Canadians. American Journal of Public Health, 106(6), 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantalone, D. W., Nelson, K. M., Batchelder, A. W., Chiu, C., Gunn, H. A., & Horvath, K. J. (2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis of combination behavioral interventions co-targeting psychosocial syndemics and HIV-related health behaviors for sexual minority men. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(6), 681–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, D. D., Tabler, J., Okumura, M. J., & Nagata, J. M. (2022). Investigating protective factors associated with mental health outcomes in sexual minority youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(3), 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, L. A., Bell, T. S., Benibgui, M., Helm, J. L., & Hastings, P. D. (2018). The buffering effect of peer support on the links between family rejection and psychosocial adjustment in LGB emerging adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(6), 854–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, P. B., Sutter, M. E., Trujillo, M. A., Henry, R. S., & Pugh, M. (2020). The minority strengths model: Development and initial path analytic validation in racially/ethnically diverse LGBTQ individuals. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, L. F., & Scheitle, C. P. (2018). Sexual orientation and psychological distress: Differences by race and gender. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 22(3), 204–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestage, G., Hammoud, M., Jin, F., Degenhardt, L., Bourne, A., & Maher, L. (2018). Mental health, drug use and sexual risk behavior among gay and bisexual men. International Journal of Drug Policy, 55, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proulx, J., & Aldwin, C. M. (2015). Effects of coping on psychological and physical health. In The encyclopedia of adulthood and aging (1st ed., pp. 1–5). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustejovsky, J. E. (2024). clubSandwich: Cluster-robust (sandwich) variance estimators with small-sample corrections. (Version R package version 0.5.10.9999) [Computer software]. Available online: http://jepusto.github.io/clubSandwich/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Pustejovsky, J. E., & Tipton, E. (2018). Small-sample methods for cluster-robust variance estimation and hypothesis testing in fixed effects models. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 36(4), 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Riley, K., & McLaren, S. (2019). Relationship status and suicidal behavior in gay men: The role of thwarted belongingness and hope. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(5), 1452–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, E. R., Lee, M. F., Simpson, K., Kelley, N. J., Sedikides, C., & Angus, D. J. (2024). Authenticity, well-being, and minority stress in LGB individuals: A scoping review. Journal of Homosexuality, 72(7), 1331–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, W. S., Legate, N., Weinstein, N., & Rahman, Q. (2017). Autonomy support fosters lesbian, gay, and bisexual identity disclosure and wellness, especially for those with internalized homophobia. Journal of Social Issues, 73(2), 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, B. F., Denning, D. M., Elbe, C. I., Maki, J. L., & Brochu, P. M. (2023). Status, sexual capital, and intraminority body stigma in a size-diverse sample of gay men. Body Image, 45, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M. (1996). A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: Conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology, 24(2), 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. G., Hart, T. A., Kidwai, A., Vernon, J. R. G., Blais, M., & Adam, B. (2017). Results of a pilot study to ameliorate psychological and behavioral outcomes of minority stress among young gay and bisexual men. Behavior Therapy, 48(5), 664–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solazzo, A., Brown, T. N., & Gorman, B. K. (2018). State-level climate, anti-discrimination law, and sexual minority health status: An ecological study. Social Science & Medicine, 196, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stall, R., Mills, T. C., Williamson, J., Hart, T., Greenwood, G., Paul, J., Binson, D., Osmond, D., & Catania, J. A. (2003). Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 93(6), 939–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanski, D. M. (2006). Does internalized heterosexism moderate the link between heterosexist events and lesbians’ psychological distress? Sex Roles, 54(3–4), 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D. M. (2009). Examining potential moderators of the link between heterosexist events and gay and bisexual men’s psychological distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, M. (2020). Sexual racism is associated with lower self-esteem and life satisfaction in men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(1), 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toomey, R. B., Ryan, C., Diaz, R. M., & Russell, S. T. (2011). High school gay–straight alliances (GSAs) and young adult well-being: An examination of GSA presence, participation, and perceived effectiveness. Applied Developmental Science, 15(4), 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, R. M., & Harper, G. W. (2020). Racialized sexual discrimination (RSD) in the age of online sexual networking: Are young Black gay/bisexual men (YBGBM) at elevated risk for adverse psychological health? American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(3–4), 504–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y., Chung, M. C., Wang, N., Yu, X., & Kenardy, J. (2021). Social support and posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 85, 101998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R. B., Walford, W. A., & Espnes, G. A. (2000). Coping styles and psychological health in adolescents and young adults: A comparison of moderator and main effects models. Australian Journal of Psychology, 52(3), 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadavaia, J. E., & Hayes, S. C. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy for self-stigma around sexual orientation: A multiple baseline evaluation. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(4), 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z., Toomey, R. B., & Anhalt, K. (2024). Sexual orientation-based victimization and internalized homonegativity among Latinx sexual minority youth: The moderating effects of social support and school level. Journal of Homosexuality, 71(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall (N = 465) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 35.8 (12.3) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 33.2 [18.2, 81.9] |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Gay | 397 (85.4%) |

| Bisexual | 48 (10.3%) |

| Other | 20 (4.3%) |

| Annual Income, CAD | |

| <CAD 20,000 | 183 (39.4%) |

| CAD 20,000–CAD 39,000 | 134 (28.8%) |

| CAD 40,000–CAD 59,000 | 71 (15.3%) |

| CAD 60,000–CAD 79,000 | 37 (8.0%) |

| >CAD 80,000 | 38 (8.2%) |

| Missing | 2 (0.4%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 273 (58.7%) |

| Black | 32 (6.9%) |

| South Asian | 32 (6.9%) |

| East/Southeast Asian | 32 (6.9%) |

| Middle Eastern/North African | 9 (1.9%) |

| Latin American | 27 (5.8%) |

| First Nations/Metis/Inuit | 4 (0.9%) |

| Mixed race | 49 (10.5%) |

| Other/unidentified | 7 (1.5%) |

| HIV serostatus | |

| HIV negative | 445 (95.7%) |

| Unknown HIV status | 15 (3.2%) |

| Other | 4 (0.9%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.2%) |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CTQ-EA | 10.72 | 5.03 | ||||||||

| 2. CTQ-PA | 7.73 | 3.74 | 0.66 ** | |||||||

| [0.63, 0.69] | ||||||||||

| 3. CTQ-SA | 7.60 | 4.77 | 0.46 ** | 0.46 ** | ||||||

| [0.41, 0.50] | [0.41, 0.50] | |||||||||

| 4. IHS | 15.36 | 6.66 | 0.15 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.23 ** | |||||

| [0.10, 0.21] | [0.05, 0.16] | [0.17, 0.28] | ||||||||

| 5. HHRDS | 22.71 | 10.30 | 0.34 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.24 ** | ||||

| [0.29, 0.39] | [0.32, 0.41] | [0.27, 0.37] | [0.19, 0.29] | |||||||

| 6. MSPSS | 43.97 | 10.20 | −0.28 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.26 ** | |||

| [−0.33, −0.23] | [−0.21, −0.10] | [−0.19, −0.08] | [−0.22, −0.11] | [−0.31, −0.20] | ||||||

| 7. HHI | 37.57 | 6.07 | −0.20 ** | −0.06 * | −0.05 | −0.19 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.48 ** | ||

| [−0.25, −0.15] | [−0.11, −0.00] | [−0.10, 0.01] | [−0.25, −0.14] | [−0.26, −0.15] | [0.43, 0.52] | |||||

| 8. RSES | 20.57 | 6.16 | −0.26 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.24 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.67 ** | |

| [−0.31, −0.21] | [−0.20, −0.09] | [−0.20, −0.09] | [−0.33, −0.23] | [−0.29, −0.19] | [0.32, 0.42] | [0.64, 0.70] | ||||

| 9. CES-D | 16.59 | 11.58 | 0.35 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.40 ** | −0.39 ** | −0.59 ** | −0.56 ** |

| [0.30, 0.40] | [0.23, 0.33] | [0.16, 0.27] | [0.26, 0.36] | [0.35, 0.44] | [−0.44, −0.34] | [−0.62, −0.55] | [−0.59, −0.52] |

| Unconditional Model | Conditional Model | Interaction Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 16.92 | 15.98–17.87 | <0.001 | 43.01 | 36.03–49.99 | <0.001 | 39.23 | 28.12–50.34 | <0.001 |

| visit (L) | 2.15 | 0.65–3.65 | 0.005 | 2.2 | 0.70–3.70 | 0.004 | |||

| visit (Q) | −1.04 | −1.77–−0.31 | 0.005 | −1.06 | −1.79–−0.33 | 0.004 | |||

| age + | −0.01 | −0.07–0.05 | 0.711 | −0.01 | −0.07–0.05 | 0.770 | |||

| bisexuality + | −0.34 | −2.67–2.00 | 0.777 | −0.16 | −2.47–2.14 | 0.889 | |||

| other sexuality + | −1.94 | −6.45–2.57 | 0.398 | −1.93 | −6.32–2.47 | 0.389 | |||

| low income | 1.41 | 0.02–2.80 | 0.047 | 1.34 | −0.05–2.73 | 0.058 | |||

| high income | −1.73 | −3.18–−0.27 | 0.020 | −1.85 | −3.30–−0.40 | 0.012 | |||

| race/ethnicity + | −0.12 | −1.44–1.21 | 0.862 | 0.06 | −1.27–1.39 | 0.928 | |||

| childhood SA + | 0.04 | −0.13–0.20 | 0.679 | 0.55 | −0.18–1.27 | 0.137 | |||

| childhood PA + | 0.35 | 0.07–0.62 | 0.013 | 0.06 | −0.89–1.01 | 0.899 | |||

| childhood EA + | 0.12 | −0.07–0.30 | 0.226 | 0.41 | −0.24–1.06 | 0.214 | |||

| Within-person effects | |||||||||

| discrimination | 0.14 | 0.07–0.21 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.07–0.21 | <0.001 | |||

| IH | 0.22 | 0.10–0.34 | <0.001 | 0.22 | 0.10–0.34 | <0.001 | |||

| self-esteem | −0.23 | −0.37–−0.09 | 0.002 | −0.22 | −0.36–−0.08 | 0.002 | |||

| social support | −0.08 | −0.15–−0.01 | 0.026 | −0.08 | −0.15–−0.01 | 0.023 | |||

| hope | −0.76 | −0.91–−0.61 | <0.001 | −0.75 | −0.90–−0.60 | <0.001 | |||

| Between-person effects | |||||||||

| discrimination | 0.15 | 0.06–0.24 | 0.001 | 0.51 | 0.20–0.82 | 0.001 | |||

| IH | 0.18 | 0.05–0.32 | 0.008 | −0.47 | −1.08–0.13 | 0.125 | |||

| hope | −0.63 | −0.82–−0.44 | <0.001 | −0.64 | −0.84–−0.45 | <0.001 | |||

| self-esteem | −0.42 | −0.61–−0.24 | <0.001 | −0.42 | −0.61–−0.23 | <0.001 | |||

| social support | −0.11 | −0.20–−0.01 | 0.022 | 0 | −0.23–0.23 | 0.978 | |||

| Interaction terms | |||||||||

| child SA × SS a | −0.01 | −0.03–0.00 | 0.161 | ||||||

| child PA × SS a | 0.01 | −0.02–0.03 | 0.613 | ||||||

| child EA × SS a | −0.01 | −0.02–0.01 | 0.396 | ||||||

| discrim b × SS b | 0 | −0.00–0.01 | 0.287 | ||||||

| IH b × SS b | −0.00 | −0.01–0.00 | 0.212 | ||||||

| discrim a × SS a | −0.01 | −0.02–−0.00 | 0.016 | ||||||

| IH a × SS a | 0.02 | 0.00–0.03 | 0.024 | ||||||

| Random Effects | |||||||||

| σ2 | 47.05 | 35.83 | 35.65 | ||||||

| τ00 | 88.88 ID | 28.70 ID | 26.96 ID | ||||||

| τ11 | 0.10 ID.visit | 0.20 ID.visit | |||||||

| ρ01 | 0.23 ID | 0.27 ID | |||||||

| ICC | 0.65 | 0.45 | 0.44 | ||||||

| N | 465 ID | 459 ID | 459 ID | ||||||

| Observations | 1260 | 1235 | 1235 | ||||||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.000/0.654 | 0.513/0.733 | 0.523/0.735 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghauri, Y.; Berlin, G.W.; Skakoon-Sparling, S.; Zahran, A.; Brennan, D.J.; Adam, B.D.; Hart, T.A. Examining Longitudinal Risk and Strengths-Based Factors Associated with Depression Symptoms Among Sexual Minority Men in Canada. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070839

Ghauri Y, Berlin GW, Skakoon-Sparling S, Zahran A, Brennan DJ, Adam BD, Hart TA. Examining Longitudinal Risk and Strengths-Based Factors Associated with Depression Symptoms Among Sexual Minority Men in Canada. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):839. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070839

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhauri, Yusuf, Graham W. Berlin, Shayna Skakoon-Sparling, Adhm Zahran, David J. Brennan, Barry D. Adam, and Trevor A. Hart. 2025. "Examining Longitudinal Risk and Strengths-Based Factors Associated with Depression Symptoms Among Sexual Minority Men in Canada" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070839

APA StyleGhauri, Y., Berlin, G. W., Skakoon-Sparling, S., Zahran, A., Brennan, D. J., Adam, B. D., & Hart, T. A. (2025). Examining Longitudinal Risk and Strengths-Based Factors Associated with Depression Symptoms Among Sexual Minority Men in Canada. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070839