“Diagnosis in the Prime of Your Life”: Facilitator Perspectives on Adapting the Living Well with Dementia (LivDem) Post-Diagnostic Course for Younger Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Young-Onset Dementia

1.2. The LivDem Post-Diagnostic Course

1.3. Adapting LivDem for Younger Adults

1.4. Research Questions

- What are the psychosocial challenges faced by younger adults following a dementia diagnosis?

- How can LivDem best be adapted to meet the needs of younger people following diagnosis?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analysis

2.5. Reflexive Statement

3. Results

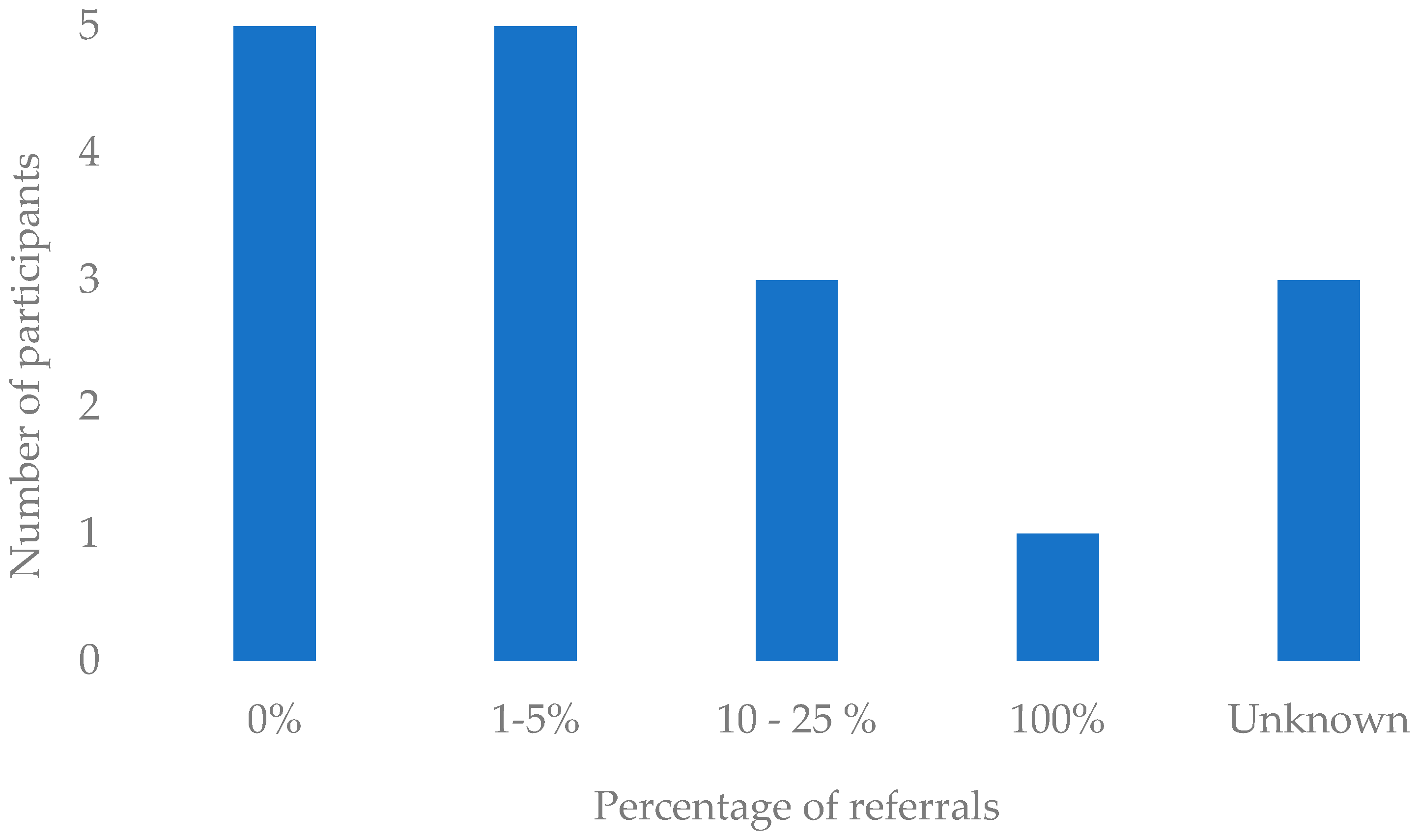

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Reflexive Thematic Analysis

3.2.1. Theme 1: “The Domino Effect”: Unique Challenges for Younger Adults

Subtheme 1: ‘Life and Opportunities Stripped Away’

Antony: “Particularly concerned about employment and financial worries if they can no longer work (or drive) following diagnosis.”

Natalie: “Acknowledging the trauma of losing your job/fear of losing your job.”

Natalie: “Lack of role and sense of purpose (in addition to reduced finances) if they have to stop work.”

Ophelia: “Driving is also a key issue—where individuals may already [have] been advised to stop driving, which obviously impacts significantly on independence and access to occupations.”

Kiera: “A loss of self can often be more problematic for this age group as they are still in the thick of developing their various roles & positions societally. There’s often more anger & frustration at having life & opportunities stripped away.”

Natalie: “Having this diagnosis in the “prime” of your life…”

Antony: “Shock at the diagnosis as it is ‘too early’ for this problem, it is something that happens to much older people.”

Subtheme 2: ‘Impacting on Everyone’: Changes in Roles and Relationships

Kiera: “The decision about whether or not to tell the people around them carries even more significance, because of the additional impact it has on others … the knock-on effects on loved ones can be carried with guilt & shame.”

Natalie: “Impact of changes of role within the family unit, having child, grandchild and/or elderly parent responsibilities. The domino effect of one element impacting on everyone (emotionally, practically and financially).”

Debbie: “Concerns about not being able to support their children or to get to know their grandchildren.”

Antony: “Uneasy that their adult children may be thrust into the role of caring for them so soon compared to someone diagnosed in their late 70s or 80s.”

Antony: “Particular dynamics which may be more prevalent in younger people’s minds might include the effect on possible sexual intimacy and their relationship with partner/spouse.”

3.2.2. Theme Two: ‘Good to Be with Peers’: The Importance of Age-Appropriate Support

Subtheme: Groups ‘Full of Old People’

Eva: “For most part those with YOD have not gained a lot from joining a group of older adults. They tend to assign themselves as ‘carers to the elderly participants’ rather than being able to focus on their own struggles.”

Natalie: “Not age appropriate. Very much in the minority. Needs were over-shadowed by the majority attending (older people).”

Ophelia: “…some people report feeling alienated if other group members are much older than them or content is not suited to their age experiences.”

Subtheme: Groups ‘Specifically for Younger People’

Natalie: “Good to be with peers/people their own age or of a similar age. Shared experience.”

Jane: “If there were enough people living with young onset dementia referred then I think it would be of great benefit to run a course specifically for this client group. Peer support is always the most beneficial outcome of the course cited by attendees.”

Ophelia: “One specifically for younger people and their families. They feed back the value of meeting with others who are in a similar situation (for family members too) and also learning about information and resources that can help.”

Debbie: “It might be harder for people with younger onset dementia to adjust to their diagnosis because it might be more unexpected, and they could feel more isolated/disconnected from those around them due to their age and seeing that others of a similar age are not experiencing the same types of problems that they are.”

Antony: “Although we do not have enough referrals for people with young onset dementia, we do try to stream referrals so that there will be at least one other person in the group who is a similar age (i.e., under 65).”

Charlotte: “Younger people may still be in work and so do not have the time to attend sessions…hence why having the online sessions would be a useful option too. It also means you could reach people regardless of distance. Younger people are usually better gripped with technology to attend online sessions compared to older adults.”

Kiera: “In person groups are more appropriate when trying to build trust & open up potentially weighty conversations. It’s easier to focus when you’re not online. You can comfort someone properly f2f if they become upset or overwhelmed.”

Fiona: “People prefer different ways so offering both may help with engagement. Sometimes having an online option is more convenient and easier to attend. Sometime people prefer the face-to-face interaction, and it is easier to interact and build relationships.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Young-Onset Dementia and LivDem: Online Survey Questions

- 1.

- What number/proportion of people referred to your service have young onset dementia?

- Response option: open text.

- 2.

- From your knowledge of LivDem, how likely are you to recommend the course to younger adults living with dementia?

- Response options: Likert scale

- ○

- Very Likely.

- ○

- Likely.

- ○

- Unlikely.

- ○

- Very Unlikely.

- 3.

- Can you explain the reason for your answer?

- Response option: open text.

- 4.

- In your experience how likely is it that a person diagnosed with young onset dementia knows what dementia is?

- Response options: Likert scale

- ○

- Very Likely.

- ○

- Likely.

- ○

- Unlikely.

- ○

- Very Unlikely.

- 5.

- In your experience do people with young onset dementia have any common misconceptions about what dementia will be like?

- Response option: open text.

- 6.

- In your experience do younger adults living with dementia have any specific concerns that differ from those of older adults living with dementia? (e.g., employment, young families)

- Response option: open text.

- 7.

- Have any of the people with young onset dementia that your service has worked with attended a LivDem Course?

- Response options: Forced choice

- ○

- Yes.

- ○

- No.

- ○

- Do Not Know.

- ○

- Other.

- 8.

- If the answer to question 7 was yes, what did participants with young onset dementia mention about their experiences of attending the sessions?

- Response option: open text.

- 9.

- Have any of the people with young onset dementia that your service has worked with attended a dementia support group other than LivDem?

- Response options: Forced choice

- ○

- Yes.

- ○

- No.

- ○

- Do Not Know.

- ○

- Other.

- 10.

- If the answer to question 9 was yes, what did they mention about their experience of attending that group?

- Response option: open text.

- 11.

- What method of facilitating a LivDem course session do you think would be most appropriate for younger adults living with dementia?

- Response options:

- ○

- In-Person.

- ○

- Online.

- ○

- Mix of In-Person and Online.

- ○

- Other.

- 12.

- Please Explain the reason for your answer

- Response option: open text.

- 13.

- Please use the text space below to comment on any additional information you think would be important when adapting the LivDem course to younger adults living with dementia

- Response option: open text.

References

- Alzheimer’s Research UK. (2023). Statistics about dementia. Available online: https://www.dementiastatistics.org/about-dementia/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Bamford, C., Wheatley, A., Brunskill, G., Booi, L., Allan, L., Banerjee, S., Harrison Dening, K., Manthorpe, J., & Robinson, L. (2021). Key components of post-diagnostic support for people with dementia and their carers: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 16(12), e0260506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannon, S. M., Grunberg, V. A., Reichman, M., Popok, P. J., Traeger, L., Dickerson, B. C., & Vranceanu, A. M. (2021). Thematic analysis of dyadic coping in couples with young-onset dementia. JAMA Network Open, 4(4), e216111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berglund, M., Gillsjö, C., & Svanström, R. (2019). Keys to person-centred care to persons living with dementia–experiences from an educational program in Sweden. Dementia, 18(7–8), 2695–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, D., Dröes, R. M., & Evans, S. (2017). Framing outcomes of post-diagnostic psychosocial interventions in dementia: The Adaptation-Coping Model and adjusting to change. Working with Older People, 21(1), 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busted, L. M., Nielsen, D. S., & Birkelund, R. (2020). “Sometimes it feels like thinking in syrup”: The experience of losing sense of self in those with young onset dementia. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(1), 1734277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K. A., Orr, E., Durepos, P., Nguyen, L., Li, L., Whitmore, C., Gehrke, P., Graham, L., & Jack, S. M. (2021). Reflexive thematic analysis for applied qualitative health research. The Qualitative Report, 26(6), 2011–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcaillon-Bentata, L., Quintin, C., Boussac-Zarebska, M., & Elbaz, A. (2021). Prevalence and incidence of young onset dementia and associations with comorbidities: A study of data from the French national health data system. PLoS Medicine, 18(9), e1003801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J., Jackson, M., Gleisner, Z., & Verne, J. (2022). Prevalence of all cause young onset dementia and time lived with dementia: Analysis of primary care health records. Journal of Dementia Care, 30(3), 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cations, M. A. (2023). A devastating loss: Driving cessation due to young onset dementia. Age and Ageing, 52(9), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheston, R. (2021). Attended dementia: Managing the terror of dementia. Bulletin of the BPS Faculty of Psychology of Older People, 156, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheston, R., & Christopher, G. (2019). Confronting the existential threat of dementia: An exploration into emotion regulation. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cheston, R., & Dodd, E. (2020). The LivDem model of post diagnostic support for people living with dementia: Results of a survey about use and impact. Psychology of Older People: The FPOP Bulletin, 1, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheston, R., Dodd, E., & Woodstoke, N. S. (2023, June 22). Using assimilation to track changes in talk during a Living Well with Dementia (LivDem) group. Society for Psychotherapy Research Annual Conference, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Cheston, R., & Marshall, A. (2019). The Living Well with Dementia course: A workbook for facilitators. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chirico, I., Ottoboni, G., Linarello, S., Ferriani, E., Marrocco, E., & Chattat, R. (2022). Family experience of young-onset dementia: The perspectives of spouses and children. Aging & Mental Health, 26(11), 2243–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, R., De Cola, M. C., Leonardi, S., Portaro, S., Naro, A., Torrisi, M., Marra, A., Bramanti, A., & Calabrò, R. S. (2021). How patients with mild dementia living in a nursing home benefit from dementia cafés: A case-control study focusing on psychological and behavioural symptoms and caregiver burden. Psychogeriatrics, 21(4), 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dementia UK. (2025). What is dementia? Available online: https://www.dementiauk.org/information-and-support/about-dementia/what-is-dementia/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- El Baou, C., Saunders, R., Buckman, J. E., Richards, M., Cooper, C., Marchant, N. L., Desai, R., Bell, G., Fearn, C., Pilling, S., & et al. (2024). Effectiveness of psychological therapies for depression and anxiety in atypical dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 20(12), 8844–8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritzen, E. V., Kohl, G., Orrell, M., & McDermott, O. (2023). Peer support through video meetings: Experiences of people with young onset dementia. Dementia, 22, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giebel, C., Eastham, C., Cannon, J., Wilson, J., & Pearson, A. (2020). Evaluating a young onset dementia service from two sides of the coin: Staff and service user perspectives. BMC Health Services Research, 20, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, N., & Smith, R. (2016). The experiences of people with young-onset dementia: A meta-ethnographic review of the qualitative literature. Maturitas, 92, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, N., Smith, R., Akhtar, F., & Richardson, A. (2017). A qualitative study of carers’ experiences of dementia cafés: A place to feel supported and be yourself. BMC Geriatrics, 17, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P. B., & Keady, J. (2009). Selfhood in younger onset dementia: Transitions and testimonies. Aging Mental Health, 13, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holdsworth, K., & McCabe, M. (2018). The impact of younger-onset dementia on relationships, intimacy, and sexuality in midlife couples: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(1), 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, I. A., & Jackman, L. (2017). Understanding behaviour in dementia that challenges: A guide to assessment and treatment. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Javadi, M., & Zarea, K. (2016). Understanding thematic analysis and its pitfalls. Journal of Client Care, 1(1), 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22(140), 55. [Google Scholar]

- Mercy, L., Hodges, J. R., Dawson, K., Barker, R. A., & Brayne, C. (2008). Incidence of early-onset dementias in Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom. Neurology, 71(19), 1496–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millenaar, J. K., Bakker, C., Koopmans, R. T., Verhey, F. R., Kurz, A., & de Vugt, M. E. (2016). The care needs and experiences with the use of services of people with young-onset dementia and their caregivers: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(12), 1261–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthukrishna, M., Bell, A. V., Henrich, J., Curtin, C. M., Gedranovich, A., McInerney, J., & Thue, B. (2020). Beyond Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) psychology: Measuring and mapping scales of cultural and psychological distance. Psychological Science, 31(6), 678–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwadiugwu, M. (2021). Early-onset dementia: Key issues using a relationship-centred care approach. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 97(1151), 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M. (2013). The social model of disability: Thirty years on. Disability & Society, 28(7), 1024–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Popok, P. J., Reichman, M., LeFeber, L., Grunberg, V. A., Bannon, S. M., & Vranceanu, A. M. (2022). One diagnosis, two perspectives: Lived experiences of persons with young-onset dementia and their care-partners. The Gerontologist, 62(9), 1311–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabanal, L. I., Chatwin, J., Walker, A., O’Sullivan, M., & Williamson, T. (2018). Understanding the needs and experiences of people with young onset dementia: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 8, e021166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, P., & Drummond, N. (2014). ‘It’s nice to have something to do’: Early-onset dementia and maintaining purposeful activity. Journal of Psychiatric and Ment Health Nursing, 21(10), 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, T. L., Rooney, D., Liddle, J., Mitchell, G., Gustafsson, L., & Pachana, N. A. (2023). A qualitative study exploring the experiences and needs of people living with young onset dementia related to driving cessation: ‘It’s like you get your legs cut off’. Age and Aging, 52(7), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamou, V., Fontaine, J. L., O’Malley, M., Jones, B., Gage, H., Parkes, J., Carter, J., & Oyebode, J. (2021). The nature of positive post-diagnostic support as experienced by people with young onset dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 25, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanberg, E., Stott, J., & Spector, A. (2010). ‘Just helping’: Children living with a parent with young onset dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 14(6), 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolhurst, E., Bhattacharyya, S., & Kingston, P. (2014). Young onset dementia: The impact of emergent age-based factors upon personhood. Dementia, 13(2), 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vliet, D., Persoon, A., Bakker, C., Koopmans, R. T., de Vugt, M. E., Bielderman, A., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2017). Feeling useful and engaged in daily life: Exploring the experiences of people with young-onset dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(11), 1889–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M., & Moser, T. (2019). The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. International Management Review, 15(1), 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Woodstoke, N. S., Winter, B., Dodd, E., & Cheston, R. (2024). “How can you think about losing your mind?”: A reflexive thematic analysis of adapting the LivDem group intervention for couples and families living with dementia. Dementia, 24(2), 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2023). Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Wright, L. (2023, October 16–28). The Living Well with Dementia course goes online co creation of an Italian group. Alzheimer Europe, Helsinki, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Young Dementia Network. (2025). What is young onset dementia? Available online: www.youngdementianetwork.org/about-youngonset-dementia/what-is-young-onset-dementia (accessed on 15 May 2023).

| Pseudonym | Age | Gender | Ethnicity | Country of Practice | Professional Background | Number of LivDem Courses Delivered or Supervised |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antony | 55 | Male | White British | UK | Support worker | 8 |

| Beth | 29 | Female | White | UK | Psychologist | 1 |

| Charlotte | 26 | Female | White British | UK | Assistant psychologist | 0 |

| Debbie | 23 | Female | White British | UK | Assistant psychologist | 0 |

| Eva | 59 | Female | White British | UK | Clinical psychologist | 5 |

| Fiona | 25 | Female | White British | UK | Assistant psychologist | 1 |

| Georgia | 23 | Female | White British | UK | Assistant psychologist | 3 |

| Heather | 26 | Female | British | UK | Assistant psychologist | 4 |

| Isabel | 42 | Female | White British | UK | Support worker | 2 |

| Jane | 49 | Female | White British | UK | Occupational therapist | 6 |

| Kiera | 36 | Female | White British | UK | Therapist | 4 |

| Layla | 46 | Female | White British | UK | Mental health nurse | 0 |

| Mary | 53 | Female | White British | UK | Therapist | 9 |

| Natalie | 49 | Female | White British | UK | Occupational therapist | 0 |

| Ophelia | 46 | Female | White British | UK | Occupational therapist | 4 |

| Themes | Subthemes | Examples of Codes | Number of Participants Coded for in Subtheme (Pseudonyms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘The domino effect’: Unique Challenges for Younger Adults | ‘Life and opportunities stripped away’ | Feelings of loss Financial worries Losing purpose and routine Loss of ability to drive impacts independence Loss of self Diagnosis in ‘prime’ of life | 10 (Antony, Beth, Debbie, Eva, Isabel, Jane, Layla, Mary, Natalie, Ophelia) |

| ‘Impacting on everyone’: changes in roles and relationships | Performing parenting duties Caring responsibilities Effects on loved ones Impact of guilt and shame due to diagnosis | 10 (Antony, Beth, Debbie, Eva, Isabel, Jane, Layla, Mary, Natalie, Ophelia) | |

| ‘Good to be with peers’: The Importance of Age Appropriate Support | Groups ‘Full of Old People’ | Not able to focus on own struggles Needs overshadowed by those of older group members Full of old people Stigma of dementia as older persons’ disease | 8 (Beth, Eva, Heather, Isabel, Jane, Layla, Natalie, Ophelia) |

| Groups ‘specifically for younger people’ | Valuable meeting others in similar situation More isolated and disconnected from age group Peer support hugely beneficial Online course accessible for people without transport Course needs more flexibility | 14 (Antony, Beth, Charlotte, Debbie, Eva, Fiona, Georgia, Isabel, Jane, Keira, Layla, Mary, Natalie, Ophelia) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wright, G.; Woodstoke, N.S.; Dodd, E.; Cheston, R. “Diagnosis in the Prime of Your Life”: Facilitator Perspectives on Adapting the Living Well with Dementia (LivDem) Post-Diagnostic Course for Younger Adults. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060794

Wright G, Woodstoke NS, Dodd E, Cheston R. “Diagnosis in the Prime of Your Life”: Facilitator Perspectives on Adapting the Living Well with Dementia (LivDem) Post-Diagnostic Course for Younger Adults. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):794. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060794

Chicago/Turabian StyleWright, Greta, Natasha S. Woodstoke, Emily Dodd, and Richard Cheston. 2025. "“Diagnosis in the Prime of Your Life”: Facilitator Perspectives on Adapting the Living Well with Dementia (LivDem) Post-Diagnostic Course for Younger Adults" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060794

APA StyleWright, G., Woodstoke, N. S., Dodd, E., & Cheston, R. (2025). “Diagnosis in the Prime of Your Life”: Facilitator Perspectives on Adapting the Living Well with Dementia (LivDem) Post-Diagnostic Course for Younger Adults. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060794