Bibliometric Analysis of Classroom Engagement: A Review Based on Web of Science Database

Abstract

1. Introduction

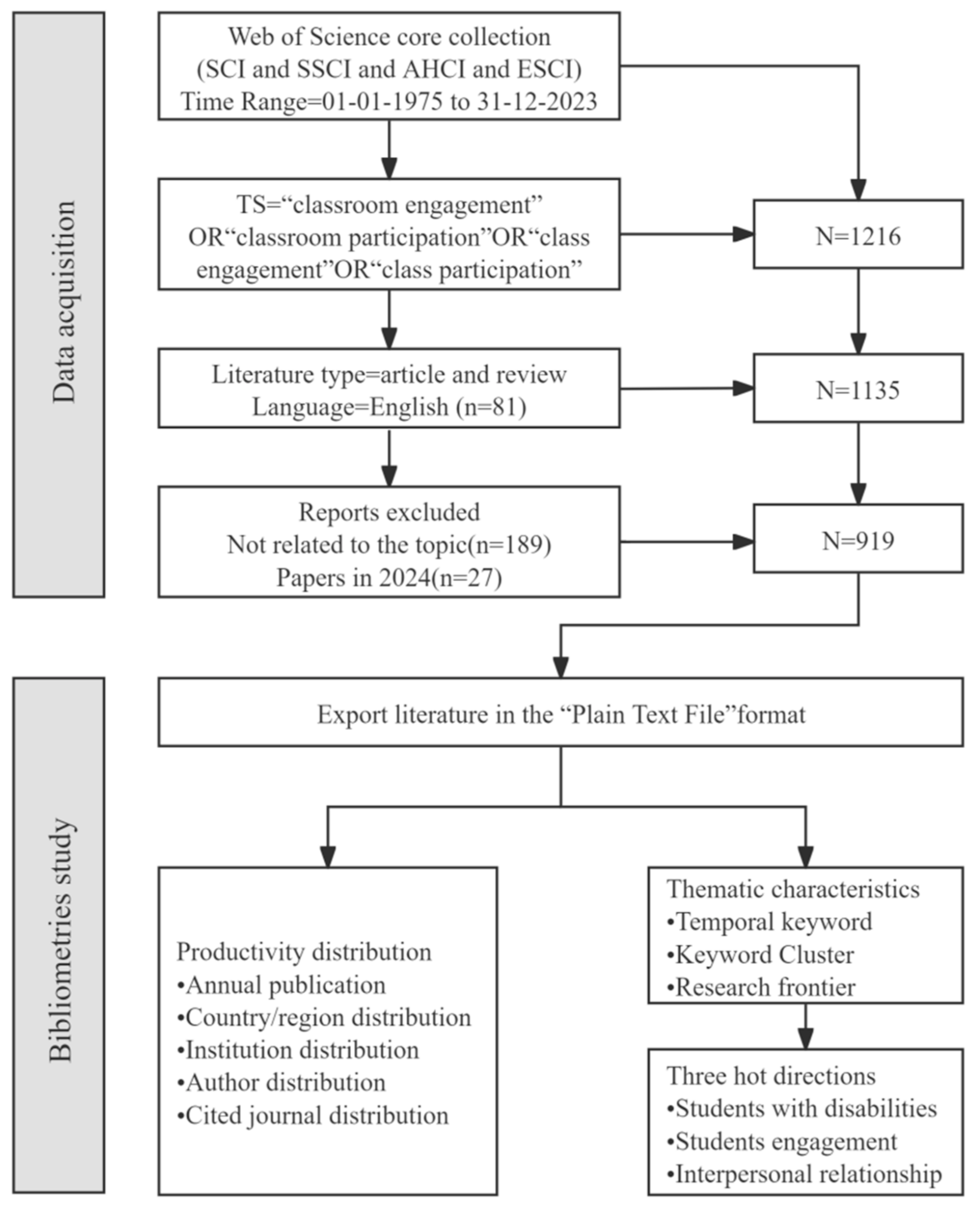

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Productivity Distribution

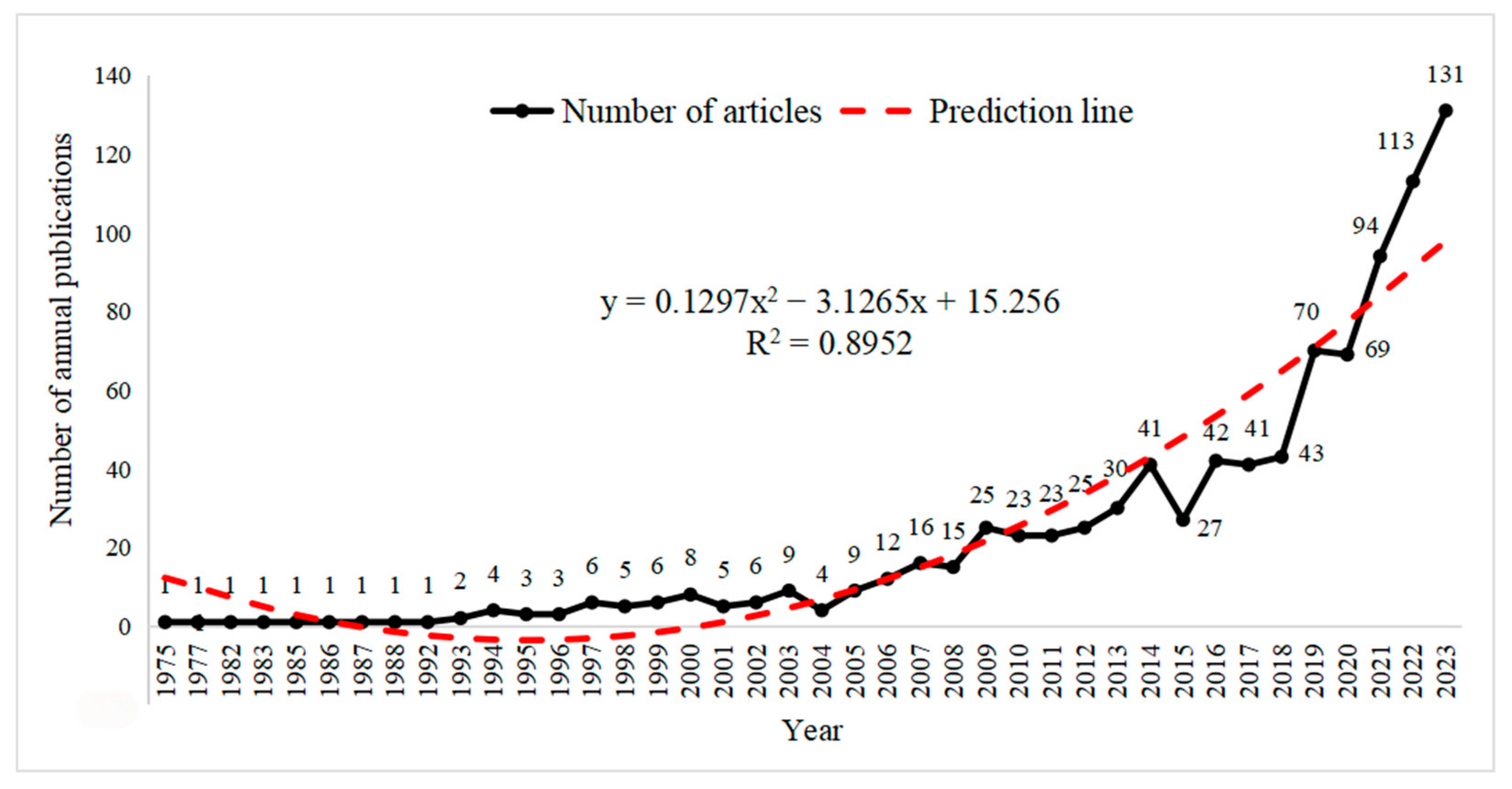

3.1.1. Analysis of Annual Publication

3.1.2. Country Distribution

3.1.3. Institutions Distribution

3.1.4. Author Distribution

3.1.5. Distribution of Cited Journals

3.2. Theme Characteristics

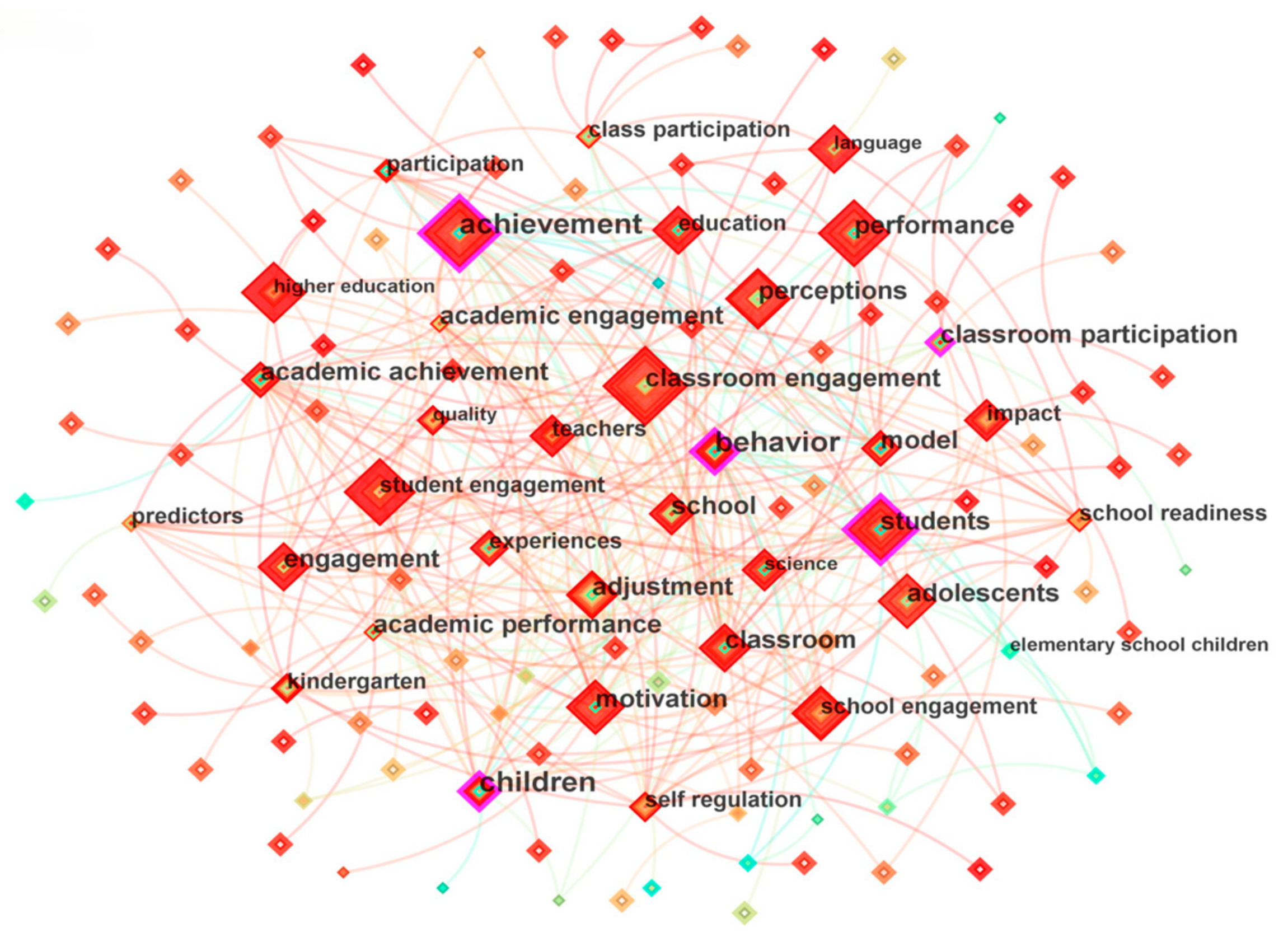

3.2.1. Co-Occurrence of Keywords

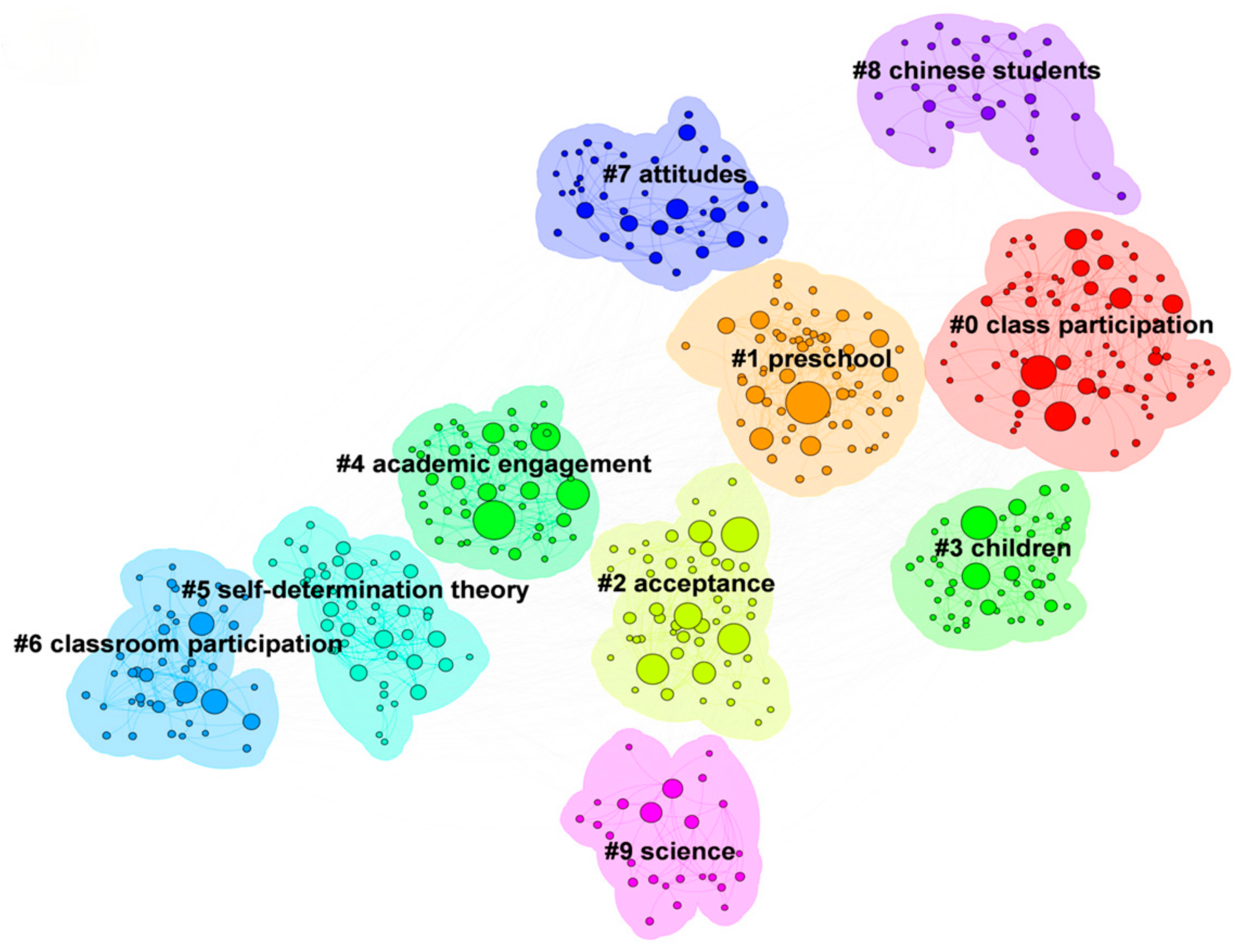

3.2.2. Analysis of Research Themes

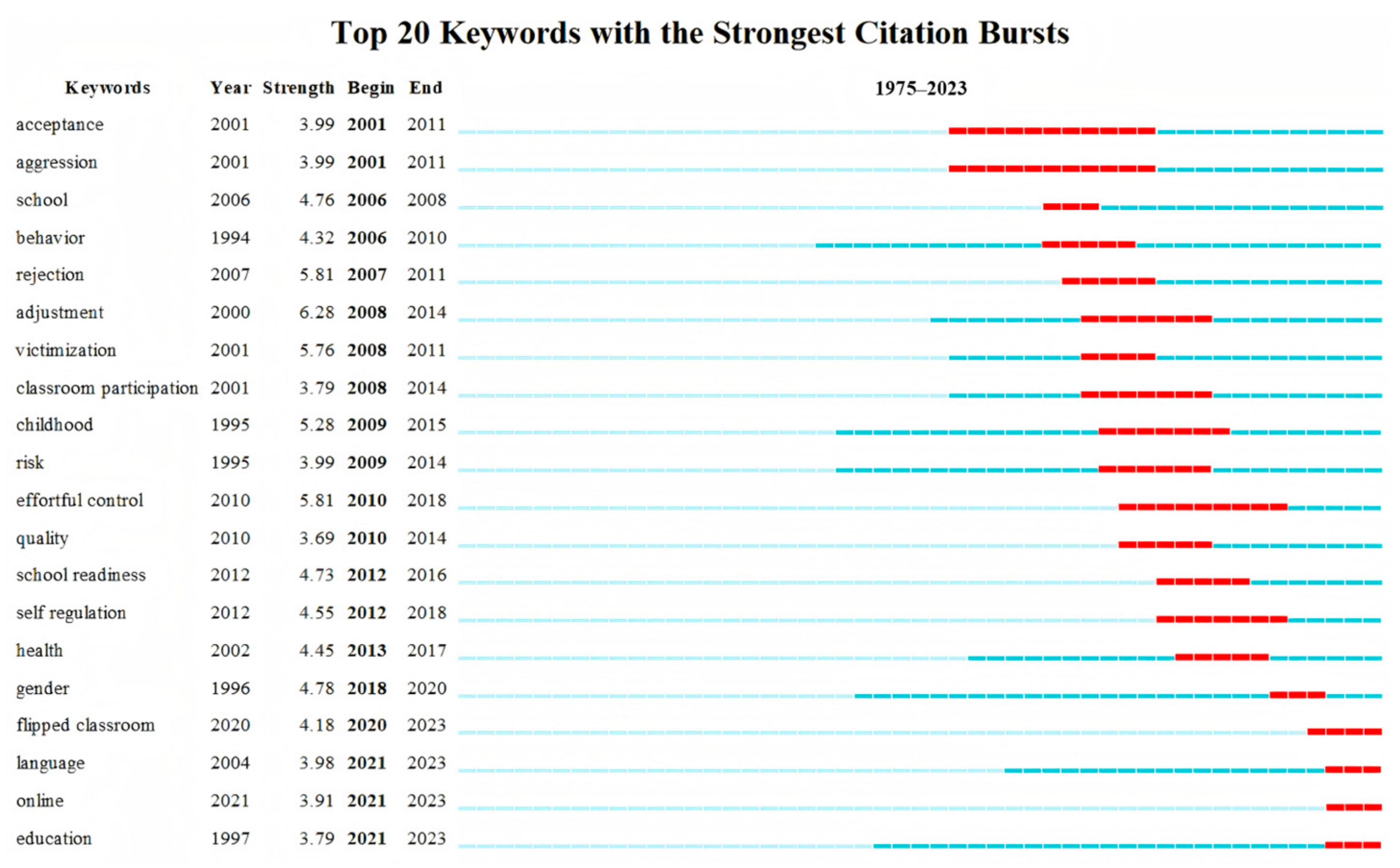

3.2.3. Research Frontier Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Productivity Distribution

4.2. Development Trends and Frontier Hotspots

4.3. Students with Disabilities and Classroom Engagement

4.4. Student Engagement

- (1)

- Cognitive Engagement

- (2)

- Emotional Engagement

- (3)

- Behavioral Engagement

- (4)

- Agentic Engagement

4.5. Interpersonal Relationships and Classroom Engagement

4.6. Self-Determination Theory

5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Practical Implications

- (1)

- Educational Policy

- (2)

- Classroom Practices

- (3)

- Teacher Development

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullah, M. Y., Bakar, N. R. A., & Mahbob, M. H. (2012). Student’s participation in classroom: What motivates them to speak up? Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 51, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Betanzos, A., & Bolón-Canedo, V. (2018). Big-data analysis, cluster analysis, and machine-learning approaches. Sex-Specific Analysis of Cardiovascular Function, 1065, 607–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amemiya, J., Fine, A., & Wang, M. T. (2020). Trust and discipline: Adolescents’ institutional and teacher trust predict classroom behavioral engagement following teacher discipline. Child Development, 91(2), 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Fallu, J., & Pagani, L. S. (2009). Student engagement and its relationship with early high school dropout. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R. (2015). Defining and measuring engagement and learning in science: Conceptual, theoretical, methodological, and analytical issues. Educational Psychologist, 50(1), 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicheng, D., Adnan, N., Harji, M. B., & Ravindran, L. (2023). Evolution and hotspots of peer instruction: A visualized analysis using CiteSpace. Education and Information Technologies, 28(2), 2245–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekaerts, M. (2016). Engagement as an inherent aspect of the learning process. Learning and Instruction, 43, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M., McGee, R., & Williams, S. (2007). Health outcomes in adolescence: Associations with family, friends and school engagement. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, E., & George, J. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on student perceptions of education and engagement. E-Journal of Business Education and Scholarship of Teaching, 15(1), 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C., Dubin, R., & Kim, M. C. (2014). Emerging trends and new developments in regenerative medicine: A scientometric update (2000–2014). Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy, 14(9), 1295–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Ye, L., & Weng, Y. (2022). Blended teaching of medical ethics during COVID-19: Practice and reflection. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christenson, S. C., Reschly, A. C., & Wylie, C. (Eds.). (2012). The handbook of research on student engagement. Springer Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, E., Chaput-Langlois, S., Fitzpatrick, C., & Garon-Carrier, G. (2023). Why children differ in classroom engagement: Insights from a prospective longitudinal cohort of elementary school students. Psychology in the Schools, 60(10), 4102–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K. R. (2013). Examining the effects of the flipped model of instruction on student engagement and performance in the secondary mathematics classroom: An action research study [Doctoral dissertation, Capella University]. [Google Scholar]

- Clemons, L. L., Mason, B. A., Garrison-Kane, L., & Wills, H. P. (2016). Self-monitoring for high school students with disabilities: A cross-categorical investigation of I-Connect. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(3), 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté-Lussier, C., & Fitzpatrick, C. (2016). Feelings of safety at school, socioemotional functioning, and classroom engagement. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(5), 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, J., Martins, J., Peseta, R., & Rosário, P. (2023). A self-regulation intervention conducted by class teachers: Impact on elementary students’ basic psychological needs and classroom engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1220536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laet, S., Colpin, H., Vervoort, E., Doumen, S., Van Leeuwen, K., Goossens, L., & Verschueren, K. (2015). Developmental trajectories of children’s behavioral engagement in late elementary school: Both teachers and peers matter. Developmental Psychology, 51(9), 1292–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinsmore, D. L., & Alexander, P. A. (2012). A critical discussion of deep and surface processing: What it means, how it is measured, the role of context, and model specification. Educational Psychology Review, 24(4), 499–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykstra Steinbrenner, J. R., & Watson, L. R. (2015). Student engagement in the classroom: The impact of classroom, teacher, and student factors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 2392–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerdemutu, L., Dewaele, J. M., & Wang, J. (2024). Developing a short language classroom engagement scale (LCES) and linking it with needs satisfaction and achievement. System, 120, 103189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegaard, O., & Wallin, J. A. (2015). The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: How great is the impact? Scientometrics, 105, 1809–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaadaway, M. A. N. (2018). The effects of a flipped classroom approach on class engagement and skill performance in a blackboard course. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(3), 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J. L., & McPartland, J. M. (1976). The concept and measurement of the quality of school life. American Educational Research Journal, 13(1), 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L., Welander, J., & Granlund, M. (2007). Participation in everyday school activities for children with and without disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 19, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59(2), 117–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, J. D. (1993). School engagement & students at risk. National Center for Education Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, C., McKinnon, R. D., Blair, C. B., & Willoughby, M. T. (2014). Do preschool executive function skills explain the school readiness gap between advantaged and disadvantaged children? Learning and Instruction, 30, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J. A., Filsecker, M., & Lawson, M. A. (2016). Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learning and Instruction, 43, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georges, A., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Malone, L. M. (2012). Links between young children’s behavior and achievement: The role of social class and classroom composition. American Behavioral Scientist, 56, 961–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gest, S. D., Domitrovich, C. E., & Welsh, J. A. (2005). Peer academic reputation in elementary school: Associations with changes in self-concept and academic skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(3), 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, B. A. (2015). Measuring cognitive engagement with self-report scales: Reflections from over 20 years of research. Educational Psychologist, 50, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardre, P. L., & Reeve, J. (2003). A motivational model of rural students’ intentions to persist in, versus drop out of, high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J. (2020). Construction of “three-stage asynchronous” instructional mode of blended flipped classroom based on mobile learning platform. Education and Information Technologies, 25(6), 4915–4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfield, P. J., & Gasper, J. (2011). The relationship between school engagement and delinquency in late childhood and early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, N., Holopainen, L., & Siekkinen, M. (2019). Children’s classroom engagement and disaffection in Vietnamese kindergartens. Educational Psychology, 39(2), 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofkens, T. L., & Pianta, R. C. (2022). Teacher–student relationships, engagement in school, and student outcomes. In Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 431–449). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J. N., Luo, W., Kwok, O., & Loyd, L. (2008). Teacher–student support, effortful engagement, and achievement: A three year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H., Reeve, J., & Halusic, M. (2016). A new autonomy-supportive way of teaching that increases conceptual learning: Teaching in students’ preferred ways. Journal of Experimental Education, 84, 686–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H., Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., & Kim, A. (2009). Can self-determination theory explain what underlies the productive, satisfying learning experiences of collectivistically-oriented South Korean adolescents? Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 644–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H., Zhou, X., Wu, H., Liu, H., & Zhang, G. (2023). A bibliometric and thematic analysis of the trends in the research on ginkgo biloba extract from 1985 to 2022. Heliyon, 9(11), e21214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y., Zhao, L., Zhu, K., Wang, H., Wang, C., & Xia, Q. (2023). Research landscape of adaptive learning in education: A bibliometric study on research publications from 2000 to 2022. Sustainability, 15(4), 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W., Mcgue, M., & Iacono, W. G. (2006). Genetic and environmental influences on academic achievement trajectories during adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 42(3), 514–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindermann, T. A., & Gest, S. D. (2018). The peer group: Linking conceptualizations, theories, and methods. In W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (2nd ed., pp. 84–105). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, G. W. (1990). Having friends, keeping friends, making friends, and being liked by peers in the classroom: Predictors of children’s early school adjustment? Child Development, 61(4), 1081–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladd, G. W., & Dinella, L. M. (2009). Continuity and change in early school engagement: Predictive of children’s achievement trajectories from first to eighth grade? Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(1), 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y. C., & Peng, L. H. (2019). Effective teaching and activities of excellent teachers for the sustainable development of higher design education. Sustainability, 12(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. H., Luo, Q., Liu, P. L., & Zhang, J. Q. (2017). Knowledge maps analysis of traditional villages research in China based on the Citespace method. Economic Geography, 37, 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T., Wang, Z., Merrin, G. J., Wan, S., Bi, K., Quintero, M., & Song, S. (2024). The joint operations of teacher-student and peer relationships on classroom engagement among low-achieving elementary students: A longitudinal multilevel study. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 77, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. (2011). School engagement: What it is and why it is important for positive youth development. In Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 41, pp. 131–160). JAI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Lerner, R. (2011). Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence:implications for grades, depression, delinquency, and substance abuse. Developmental Psychology, 47, 233e247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. D., & Zhang, B. (2023). Family-friendly policy evolution: A bibliometric study. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Xie, M., & Lian, Z. (2019). Emotional engagement and student satisfaction: A study of Chinese college students based on a nationally representative sample. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 28, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, H. M. (2000). Student engagement in instructional activity: Patterns in the elementary, middle, and high school years. American Educational Research Journal, 37(1), 153–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J., Cunha, J., Lopes, S., Moreira, T., & Rosário, P. (2022). School engagement in elementary school: A systematic review of 35 years of research. Educational Psychology Review, 34(2), 793–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, L., Reeve, J., Herrera, D., & Claux, M. (2018). Students’ agentic engagement predicts longitudinal increases in perceived autonomy-supportive teaching: The squeaky wheel gets the grease. The Journal of Experimental Education, 86(4), 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, M. M., Cameron, C. E., Connor, C. M., Farris, C. L., Jewkes, A. M., & Morrison, F. J. (2007). Links between behavioral regulation and preschoolers’ literacy, vocabulary, and math skills. Developmental Psychology, 43, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miech, R., Essex, M. J., & Goldsmith, H. H. (2001). Socioeconomic status and the adjustment to school: The role of self-regulation during early childhood. Sociology of Education, 74, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, E., Archambault, I., De Clercq, M., & Galand, B. (2019). Student self-efficacy, classroom engagement, and academic achievement: Comparing three theoretical frameworks. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, E., Morin, A. J. S., Langlois, J., Tardif-Grenier, K., & Archambault, I. (2020). Internalizing and externalizing behavior problems and student engagement in elementary and secondary school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(11), 2327–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, L. S., Fitzpatrick, C., Barnett, T. A., & Dubow, E. (2010). Prospective associations between early childhood television exposure and academic, psychosocial, and physical well-being by middle childhood. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 164(5), 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J., & Yang, Z. (2023). Knowledge mapping of relative deprivation theory and its applicability in tourism research. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 12–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patall, E. A., Pituch, K. A., Steingut, R. R., Vasquez, A. C., Yates, N., & Kennedy, A. A. (2019). Agency and high school science students’ motivation, engagement, and classroom support experiences. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 62, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patall, E. A., Steingut, R. R., Vasquez, A. C., Trimble, S. S., Pituch, K. A., & Freeman, J. L. (2018). Daily autonomy supporting or thwarting and students’ motivation and engagement in the high school science classroom. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(2), 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patall, E. A., & Zambrano, J. (2019). Facilitating student outcomes by supporting autonomy: Implications for practice and policy. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 6(2), 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijl, S. J. (2007). Introduction: The social position of pupils with special needs in regular education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 22(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-James, N., Shernoff, D. J., Bressler, D. M., Larson, S. C., & Sinha, S. (2019). Instructional interventions that support student engagement: An international perspective. In J. A. Fredricks, A. L. Reschly, & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), Handbook of student engagement interventions: Working with disengaged students (pp. 103–119). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. (2013). How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: The concept of agentic engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Lee, W. (2014). Students’ classroom engagement produces longitudinal changes in classroom motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(2), 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (Eds.). (2022). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M., Spilt, J. L., & Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research, 81(4), 493–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadjadi, E. N. (2023). Challenges and Opportunities for Education Systems with the Current Movement toward Digitalization at the Time of COVID-19. Mathematics, 11(2), 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwager, R., & Schalk, L. (2022). How systematic are systematic literature searches? Atti del 5° Convegno Sulle Didattiche Disciplinari, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selanikyo, E., Yalon-Chamovitz, S., & Weintraub, N. (2017). Enhancing classroom participation of students with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Améliorer la participation en classe des élèves ayant des déficiences intellectuelles et des troubles envahissants du développement. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 84(2), 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereno, K., Walter, N., & Brooks, J. J. (2020). Rethinking student participation in the college classroom: Can commitment and self-affirmation enhance oral participation? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 50(6), 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, M., Ulubey, O., Toraman, Ç., & Ture, E. (2014). An analysis of high school students’ classroom engagement in relation to various variables. Egitim ve Bilim-Education and Science, 39(176), 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M., Kenny, M., & McNeela, E. (2002). Curriculum access for pupils with disabilities: An Irish experience. Disability & Society, 17(2), 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H., & Chang, Y. (2022). Relational support from teachers and peers matters: Links with different profiles of relational support and academic engagement. Journal of School Psychology, 92, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E. A., Furrer, C., Marchand, G., & Kindermann, T. (2008). Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: Part of larger motivational dynamic. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P., Yi, J., Chen, X., & Xiao, Y. (2023). Visual analysis of psychological resilience research based on web of science database. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M., Liao, H., Wan, Z., Herrera-Viedma, E., & Rosen, M. A. (2018). Ten years of sustainability (2009 to 2018): A bibliometric overview. Sustainability, 10(5), 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryzin, M. J., Gravely, A. A., & Roseth, C. J. (2009). Autonomy, belongingness, and engagement in school as contributors to adolescent psychological well-being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Madriz, L. F., Konishi, C., & Wong, T. K. (2024). A meta-analysis of the association between teacher support and school engagement. Social Development, 33(4), e12745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, T. E., Lerkkanen, M. K., Poikkeus, A. M., & Kuorelahti, M. (2015). The relationship between classroom quality and students’ engagement in secondary school. Educational Psychology, 35(8), 963–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., Chow, A., Hofkens, T., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2015). The trajectories of student emotional engagement and school burnout with academic and psychological development: Findings from Finnish adolescents. Learning and Instruction, 36, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., & Degol, J. (2014). Staying engaged: Knowledge and research needs in student engagement. Child Development Perspectives, 8, 137e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012a). Adolescent behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement trajectories in school and their differential relations to educational success. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(1), 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012b). Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83(3), 877–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2013). School context, achievement motivation, and academic engagement: A longitudinal study of school engagement using a multidimensional perspective. Learning and Instruction, 28, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., & Fredricks, J. A. (2014). The reciprocal links between school engagement, youth problem behaviors, and school dropout during adolescence. Child Development, 85(2), 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., Fredricks, J. A., Ye, F., Hofkens, T. L., & Linn, J. S. (2016). The math and science engagement scales: Scale development, validation, and psychometric properties. Learning and Instruction, 43, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., Willett, J. B., & Eccles, J. S. (2011). The assessment of school engagement: Examining dimensionality and measurement invariance by gender and race/ethnicity. Journal of School Psychology, 49, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Chen, Y., Lv, X., & Xu, J. (2023). Hot topics and frontier evolution of science education research: A bibliometric mapping from 2001 to 2020. Science & Education, 32(3), 845–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehlage, G. G., & Smith, G. A. (1992). Building new programs for students at risk. In F. M. Newmann (Ed.), Student engagement and achievement in American secondary schools (pp. 92–118). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wendelborg, C., & Tøssebro, J. (2011). Educational arrangements and social participation with peers amongst children with disabilities in regular schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15(5), 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K. R., Jablansky, S., & Scalise, N. R. (2020). Peer social acceptance and academic achievement: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(1), 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wider, W., Jiang, L., Lin, J., Fauzi, M. A., Li, J., & Chan, C. K. (2024). Metaverse chronicles: A bibliometric analysis of its evolving landscape. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 40(17), 4873–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F., Ye, J., Bai, Y., Wang, H., & Wang, W. (2022). Exercise-based renal rehabilitation: A bibliometric analysis from 1969 to 2021. Frontiers in Medicine, 9, 842919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., & Akhter, S. (2023). Negative psychological and educational impacts of Corona Virus Anxiety on Chinese university students: Exploring university students’ perceptions. Heliyon, 9(10), e20373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Institutions | Count | Institutions | Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona State University | 39 | University of California System | 0.19 |

| Texas A&M University College Station | 24 | Arizona State University | 0.13 |

| University of California System | 20 | Beijing Normal University | 0.13 |

| Université de Montréal | 19 | University of Massachusetts System | 0.13 |

| University System of Ohio | 17 | University of Texas System | 0.12 |

| California State University System | 15 | University of Auckland | 0.08 |

| Pennsylvania Commonwealth System of Higher Education (PCSHE) | 13 | University of Massachusetts Boston | 0.08 |

| University of North Carolina | 12 | Cornell University | 0.07 |

| State University System of Florida | 10 | California Polytechnic State University | 0.06 |

| University of Virginia | 10 | University of Kansas | 0.06 |

| Authors | Count | Cited Authors | Cited Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fitzpatrick C | 15 | Fredricks JA | 182 |

| Pagani LS | 7 | Skinner EA | 133 |

| Hwang GJ | 5 | Ladd GW | 108 |

| Downer JT | 5 | Finn JD | 95 |

| Archambault I | 5 | Pianta RC | 80 |

| Hughes JN | 5 | Muthen LK | 77 |

| Buhs ES | 5 | Buhs ES | 74 |

| Valiente C | 4 | Hu LT | 74 |

| Reeve J | 4 | Ryan RM | 72 |

| Almqvist L | 4 | Reeve J | 69 |

| Cluster ID | Size | Silhouette | Mean (Year) | (Label) LLR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 69 | 0.77 | 2009 | class participation; active learning; east Asian students; prior knowledge; faculty |

| 1 | 64 | 0.71 | 2013 | preschool; school readiness; classroom engagement; task engagement; self-regulation |

| 2 | 51 | 0.76 | 2006 | acceptance; victimization; well-being; peer victimization; social acceptance |

| 3 | 47 | 0.85 | 2000 | children; meta-analysis; prevalence; disability; special education |

| 4 | 45 | 0.78 | 2006 | academic engagement; behavioral engagement; behavior; stress; school transition |

| 5 | 44 | 0.77 | 2012 | self-determination theory; need satisfaction; relational goals; teacher self-efficacy; achievement goals |

| 6 | 42 | 0.75 | 2006 | classroom participation; instruction; elementary students; peer acceptance; silence |

| 7 | 41 | 0.69 | 2012 | attitudes; knowledge; transition; engagement; middle school |

| 8 | 27 | 0.80 | 2020 | Chinese students; pandemic; hard of hearing; deaf; online learning |

| 9 | 26 | 0.82 | 2008 | science; women; stereotype threat; stem; peer support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, X.; Qi, C.; Zhao, G. Bibliometric Analysis of Classroom Engagement: A Review Based on Web of Science Database. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 737. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060737

Zhang Z, Zhao Y, Huang X, Qi C, Zhao G. Bibliometric Analysis of Classroom Engagement: A Review Based on Web of Science Database. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):737. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060737

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhen, Yali Zhao, Xiaoyu Huang, Chunhui Qi, and Guoxiang Zhao. 2025. "Bibliometric Analysis of Classroom Engagement: A Review Based on Web of Science Database" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 737. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060737

APA StyleZhang, Z., Zhao, Y., Huang, X., Qi, C., & Zhao, G. (2025). Bibliometric Analysis of Classroom Engagement: A Review Based on Web of Science Database. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 737. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060737