The Interplay of Self-Construal and Service Co-Workers’ Attitudes in Shaping Emotional Labor Under Customer Injustice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Customer Injustice

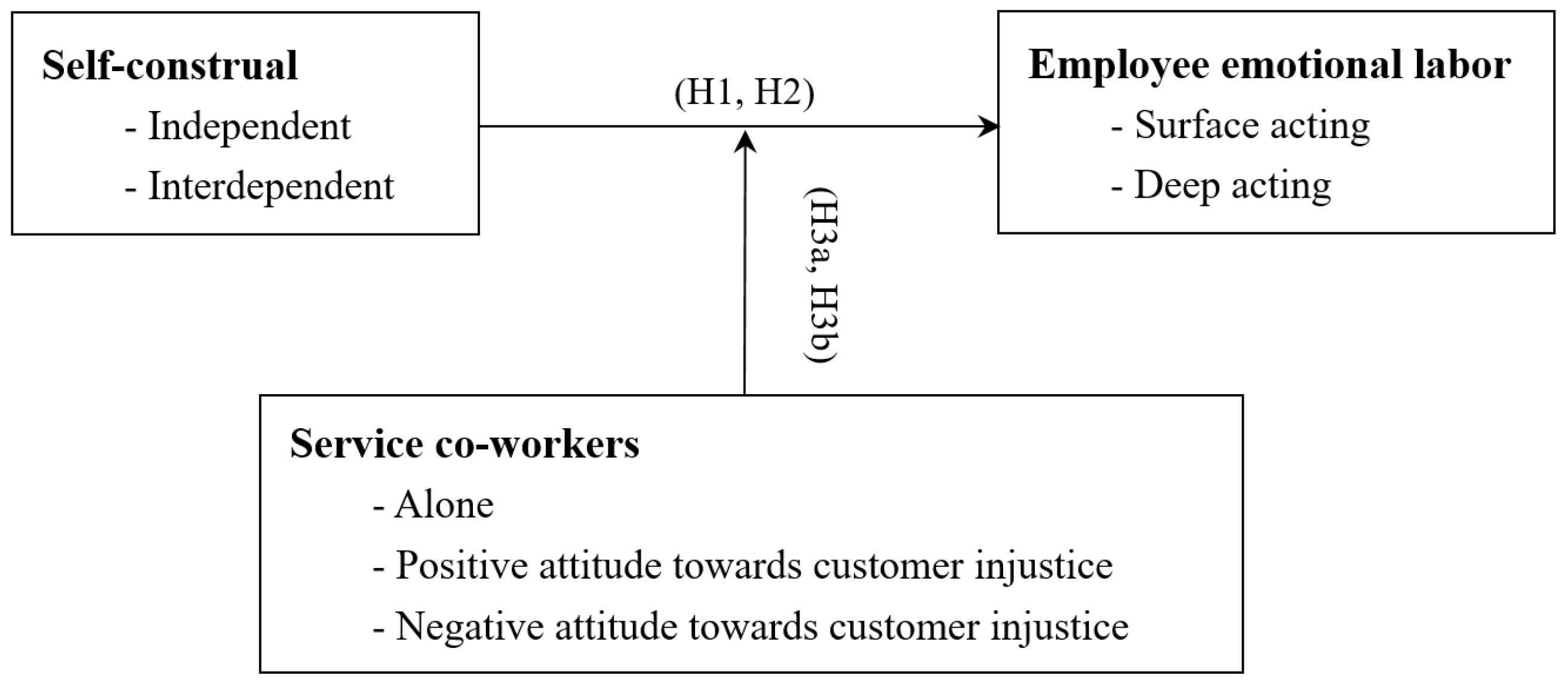

2.2. Self-Construal and Employee Emotional Labor

2.3. Joint Effect of Self-Construal and Service Co-Workers

3. Methodology

3.1. Experimental Design

- Alone: When employees work independently, emotional labor strategies are driven by self-construal (interdependent vs. independent), free from social norm interference, as posited by self-construal theory (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Independent individuals, prioritizing personal autonomy, rely more on surface acting to fulfill role requirements, whereas interdependent individuals, lacking relational cues, exhibit inconsistent emotional regulation due to the absence of social norm guidance.

- Positive: When employees work with service co-workers who hold a positive attitude toward customer injustice (e.g., maintaining a polite smile and using standard service phrases that align with company standards), these attitudes function as supportive social norms, consistent with self-construal theory’s emphasis on social norm adaptation (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Interdependent individuals, attuned to relational expectations, reduce surface acting and engage in deep acting to maintain harmony, mitigating emotional inconsistency (Grandey, 2000).

- Negative: When employees work with service co-workers who hold a negative attitude (e.g., expressing acceptable dissatisfaction through eye-rolling or sighing), these attitudes acted as discouraging social cues, aligning with impression management theory’s focus on situational conformity (Goffman, 1959). Interdependent individuals, sensitive to relational tension, increased surface acting as a defensive strategy to navigate hostility, prioritizing external harmony over genuine engagement to adapt to the shared unfairness climate.

3.2. Samples

3.3. Experimental Procedures

- Scenario 1—working alone towards customer injustice: You are a frontline employee at a high-star hotel in Shanghai, having worked there for years. One day, you are providing dining service for a table of customers alone. One of the customers is extremely picky about you, asks you in a sarcastic tone whether you are new and complains about your service, and even becomes angry with you at times. After the meal, they walk away arrogantly, without any response to your greeting of “thank you and welcome back again”, and do not even give you a direct look.

- Scenario 2—working with others who hold a positive attitude towards customer injustice: You are a frontline employee at a high-star hotel in Shanghai, having worked there for years. One day, you are providing dining service for a table of customers with your colleagues. One of the customers is extremely picky about you, asks you in a sarcastic tone whether you are new and complains about your service, and even becomes angry with you at times. After the meal, they walk away arrogantly, without any response to your greeting of “thank you and welcome back again”, and do not even give you a direct look. You know your colleagues hold a positive attitude towards such customer behaviors, maintaining a polite smile and using standard service phrases aligned with company standards.

- Scenario 3—working with others who hold a negative attitude towards customer injustice: You are a frontline employee at a high-star hotel in Shanghai, having worked there for years. One day, you are providing dining service for a table of customers with your colleagues. One of the customers is extremely picky about you, asks you in a sarcastic tone whether you are new and complains about your service, and even becomes angry with you at times. After the meal, they walk away arrogantly, without any response to your greeting of “thank you and welcome back again”, and do not even give you a direct look. You know your colleagues hold a negative attitude towards such customer behaviors, expressing subtle dissatisfaction through eye-rolling or sighing.

3.4. Measurements

- Surface acting: A statement such as “When encountering such a customer, you would merely fulfill the service as required by the hotel, and even feign a smile” was used, measured via a 7-point semantic differential scale (anchored at “completely impossible”–“completely possible”, “not inclined to do this”–“inclined to do this”, and “definitely won’t do this”–“definitely will do this”) (Chan & Wan, 2008). In this study, it demonstrated acceptable reliability with Cronbach’s α = 0.845.

- Deep acting adopted a similar format: “When encountering such a customer, you can still strive to overcome your unpleasant emotions and serve the customer wholeheartedly with an amiable attitude”, which was also measured with the same 7-point semantic differential scale (Chan & Wan, 2008). In this study, it demonstrated acceptable reliability with Cronbach’s α = 0.891.

- Dissatisfaction: It represents employees’ emotional reaction to customer injustice. As a core affective response, it can confound the relationship between self-construal and strategy choice by amplifying or dampening emotional labor demands (Ha & Jang, 2009). Adapted from Chan and Wan (2008), it was measured with a three-item scale: “Overall, you are dissatisfied with this customer’s behaviors”, “Your overall experience with this customer’s behaviors is unpleasant” and “Overall, you are satisfied with this customer’s behaviors” (reverse-scored). The scale demonstrated good internal consistency with Cronbach’s α = 0.839.

- Severity: It was used to capture employees’ subjective assessment of the seriousness of customer injustice. As a core cognitive appraisal, it directly influenced employees’ emotional intensity and subsequent emotional labor strategy choices (Craighead et al., 2004). Adapted from Maxham and Netemeyer (2002), it was measured with a single item: “In your opinion, this customer’s behavior is very serious”.

- Attributions reflect employees’ judgments on whether the customer should be held responsible for the injustice. As a core accountability appraisal, they captured causal responsibility attributions critical for distinguishing internal (self-driven) vs. external (customer-driven) emotional labor motivations and influenced employees’ causal responsibility perceptions and emotional labor coping strategies (Wei et al., 2012). Adapted from Maxham and Netemeyer (2002), this construct was measured with three items: “The customer should take responsibility for the behaviors against you”, “You would blame the customer for such incidents”, and “The customer should take full responsibility for what you have suffered”. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency with Cronbach’s α = 0.844.

- Authenticity: It was used to capture employees’ subjective assessment of the realism of the entire experimental scenario. As a core cognitive appraisal, it directly influenced the priming of the experimental context (Wei et al., 2012). Adapted from Maxham and Netemeyer (2002), it was measured with a single item: “The situation described above is real”.

4. Results

4.1. Manipulation Checks

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

4.2.1. Effects of Self-Construal on Employee Emotional Labor

4.2.2. Moderating Effects of Service Co-Workers

5. Discussion

6. Theoretical Contributions

7. Managerial Implications

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashforth, B. E., & Humphrey, R. N. (1993). Emotional labor in service roles: The influence of identity. Academy of Management Review, 18(1), 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranik, L. E., Wang, M., Gong, Y., & Shi, J. (2017). Customer mistreatment, employee health, and job performance: Cognitive rumination and social sharing as mediating mechanisms. Journal of Management, 43(4), 1261–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M. J. (1990). Evaluating service encounters: The effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C. M. (2006). A review of emotional labor and its nomological network: Practical and research implications. Ergonomia Ije&Hf, 28, 295–309. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, R. R., Lu, L., & Gursoy, D. (2018). Effect of disruptive customer behaviors on others’ overall service experience: An appraisal theory perspective. Tourism Management, 69, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H., & Xiao, L. (2014). Review of emotional work under customer injustice—From the social network perspective. Journal of University of Electronic Science and Technology of China (Social Sciences Edition), 16(5), 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H., & Wan, L. C. (2008). Consumer responses to service failures: A resource preference model of cultural influences. Journal of International Marketing, 16(1), 72–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Craighead, C. W., Karwan, K. R., & Miller, J. L. (2004). The effects of severity of failure and customer loyalty on service recovery strategies. Production and Operations Management, 13(4), 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S. E., Bacon, P. L., & Morris, M. L. (2000). The relational interdependent self-construal and relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(4), 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahling, J. J., & Perez, L. A. (2010). Older worker, different actor? Linking age and emotional labor strategies. Personality & Individual Differences, 48(5), 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, S., Horowitz, I., Weigler, H., & Basis, L. (2010). Is good character good enough? The effects of situational variables on the relationship between integrity and counterproductive work behaviors. Human Resource Management Review, 10, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandey, A. A. (2003). When the smile must go on: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 46(1), 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M. (2013). Rocking the boat but keeping it steady: The role of emotion regulation in employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1703–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J., & Jang, S. S. (2009). Perceived justice in service recovery and behavioral intentions: The role of relationship quality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(3), 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y., Chen, Q., & Alden, D. L. (2012). Consumption in the public eye: The influence of social presence on service experience. Journal of Business Research, 65(3), 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, G. H. (1989). Conservations of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmvall, C. M., & Sidhu, J. (2007). Predicting customer service employees’ job satisfaction and turnover intentions: The roles of customer interactional injustice and interdependent self-construal. Social Justice Research, 20, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D. J., & Gengler, C. (2001). Emotional contagion effects on product attitudes. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(2), 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., Scott, B. A., & Ilies, R. (2006). Hostility, job attitudes, and workplace deviance: Test of a multilevel model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., & Qu, H. (2019). The effects of experienced customer incivility on employees’ behavior toward customers and coworkers. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 43(1), 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J. (2008). Hotel service providers’ emotional labor: The antecedents and effects on burnout. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(2), 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krannitz, M. A., Grandey, A. A., Liu, S., & Almeida, D. A. (2015). Workplace surface acting and marital partner discontent: Anxiety and exhaustion spillover mechanisms. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(3), 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalwani, A. K., & Shavitt, S. (2009). The “me” I claim to be: Cultural self-construal elicits self-presentational goal pursuit. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 97(1), 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxham, J. G., III, & Netemeyer, R. G. (2002). A longitudinal study of complaining customers’ evaluations of multiple service failures and recovery efforts. Journal of Marketing, 55(4), 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milam, A. C., Spitzmueller, C., & Penney, L. M. (2009). Investigating individual differences among targets of workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(1), 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J., & Kim, H. J. (2020). Customer mistreatment and service performance: A self-consistency perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 86, 102367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y., & Kim, S. (2019). Customer mistreatment harms nightly sleep and next morning recovery: Job control and recovery self-efficacy as cross-level moderators. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(2), 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X., Wang, Y., Hu, X., & Yang, J. (2019). Social support buffers acute psychological stress in individuals with high interdependent self-construal. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 51(4), 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D. E., & Spencer, S. (2006). When customers lash out: The effects of customer interactional injustice on emotional labor and the mediating role of discrete emotions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlenker, B. R., Britt, T. W., & Pennington, J. (1996). Impression regulation and management: Highlights of a theory of self-identification. In R. M. Sorrentino, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition: The interpersonal context (pp. 118–147). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simillidou, A., Christofi, M., Glyptis, L., Papatheodorou, A., & Vrontis, D. (2020). Engaging in emotional labour when facing customer mistreatment in hospitality. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T. M. (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlicki, D. P., van Jaarsveld, D. D., & Walker, D. D. (2008). Getting even for customer mistreatment: The role of moral identity in the relationship between customer interpersonal injustice and employee sabotage. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. K., & Wagner, J. (1999). A model of customer satisfaction with service encounters involving failure recovery. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(3), 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., & Gu, Y. (2024). Influence of leaders’ emotional labor and its perceived appropriateness on employees’ emotional labor. Behavioral Sciences, 14(5), 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X., Gu, Y., & Cui, L. (2017). Influence of leader and employee emotional labor on employee on service performance: A hierarchical linear modeling approach. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 45(8), 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Jaarsveld, D. D., Restubog, S. L. D., Walker, D. D., & Amarnani, R. K. (2015). Misbehaving customers: Understanding and managing customer injustice in service organizations. Organizational Dynamics, 44(4), 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W., Miao, L., Cai, L. A., & Adler, H. (2012). The influence of self-construal and co-consumption others on consumer complaining behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T., & Liang, Y. (2020). Customers bullying and resignation intention of tour guides: A study based resource conservation theory. Tourism Science, 34(3), 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L., Gong, J., & Liang, Y. (2011a). Customer injustice and on employees’ emotional labor: The role of perspective taking and negative affectivities. Chinese Journal of Management, 8(5), 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L., Li, J., & Zhang, C. (2011b). A study of employees’ perceived customer injustice: Exploratory research based on the critical incident technique. Management Review, 23(5), 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Martinez, L. R., & Lv, Q. (2017). Explaining the link between emotional labor and turnover intentions: The role of in-depth communication. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 18(3), 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S. T., Cao, Z. C., & Huo, Y. (2020). Antecedents and outcomes of emotional labour in hospitality and tourism: A meta-analysis. Tourism Management, 79, 104099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C., Chen, Y., & Zhao, X. (2019). Emotional labor: Scale development and validation in the chinese context. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C. J., & Hwang, M. Y. (2011). Interdependence in ethnic identity and self: Implications for theory and practice. Journal of Counseling & Developing, 78(4), 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B., Zhou, Q., Liu, G., & Yu, W. (2019). Subjective norm and employees’ innovation behavior: A perspective of impression management motivation. Management Review, 31(3), 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dependent Variable | Self-Construal | N | M | SD | t | p(2-tailed) | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface acting | Independent | 72 | 5.355 | 1.048 | 2.260 | 0.025 | 0.332 |

| Interdependent | 107 | 4.968 | 1.231 | ||||

| Deep acting | Independent | 72 | 3.546 | 1.811 | −0.791 | 0.430 | 0.120 |

| Interdependent | 107 | 3.349 | 1.509 |

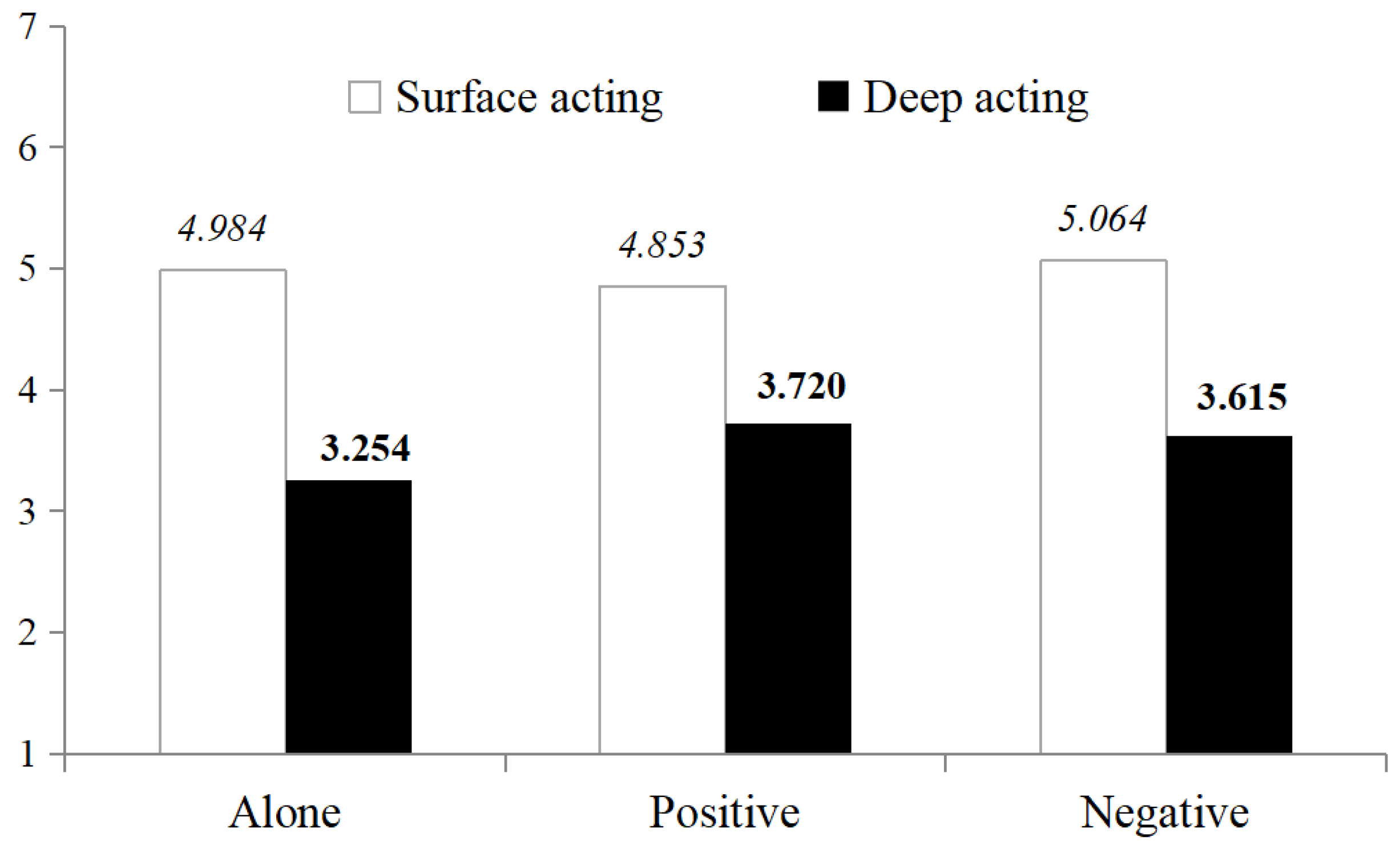

| Service Co-Workers | N | M | SD | t | p(2-tailed) | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Along | 21 | 3.254 | 1.785 | −0.838 | 0.407 | 0.246 |

| Positive | 25 | 3.720 | 1.985 | |||

| Along | 21 | 3.254 | 1.785 | −0.705 | 0.484 | 0.208 |

| Negative | 26 | 3.615 | 1.696 | |||

| Positive | 25 | 3.720 | 1.985 | 0.202 | 0.840 | 0.057 |

| Negative | 26 | 3.615 | 1.696 |

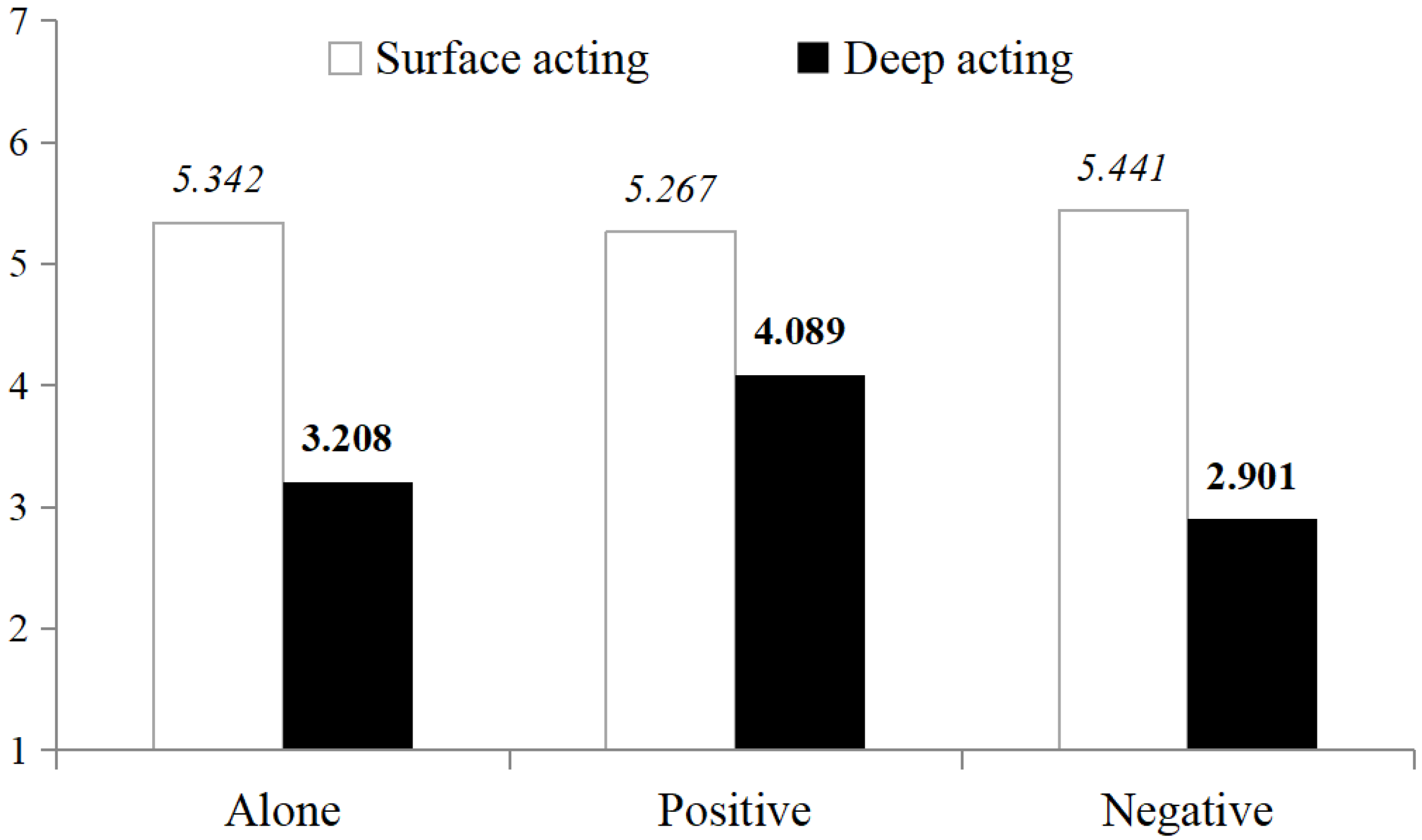

| Service Co-Workers | N | M | SD | t | p(2-tailed) | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Along | 40 | 3.208 | 1.426 | −2.178 | 0.034 | 0.546 |

| Positive | 30 | 4.089 | 1.838 | |||

| Along | 40 | 3.208 | 1.426 | 1.084 | 0.282 | 0.244 |

| Negative | 37 | 2.901 | 1.048 | |||

| Positive | 30 | 4.089 | 1.838 | 3.149 | 0.003 | 0.817 |

| Negative | 37 | 2.901 | 1.048 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, Y.; Tang, X. The Interplay of Self-Construal and Service Co-Workers’ Attitudes in Shaping Emotional Labor Under Customer Injustice. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060735

Gu Y, Tang X. The Interplay of Self-Construal and Service Co-Workers’ Attitudes in Shaping Emotional Labor Under Customer Injustice. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):735. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060735

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Yingkang, and Xiuli Tang. 2025. "The Interplay of Self-Construal and Service Co-Workers’ Attitudes in Shaping Emotional Labor Under Customer Injustice" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060735

APA StyleGu, Y., & Tang, X. (2025). The Interplay of Self-Construal and Service Co-Workers’ Attitudes in Shaping Emotional Labor Under Customer Injustice. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060735